51456 results in American studies

Preface

-

- Book:

- Who Is a True Christian?

- Published online:

- 04 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 22 February 2024, pp xi-xviii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Who Is a True Christian?

- Published online:

- 04 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 22 February 2024, pp 1-42

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 21 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 17 October 2023

Constructions of Racial Savagery in Early Twentieth-Century US Narratives of White Civilization

-

- Journal:

- Journal of American Studies / Volume 58 / Issue 2 / May 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 19 February 2024, pp. 193-219

- Print publication:

- May 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Writing about the Merovingians in the Early United States

-

- Published by:

- Amsterdam University Press

- Published online:

- 17 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 31 August 2023

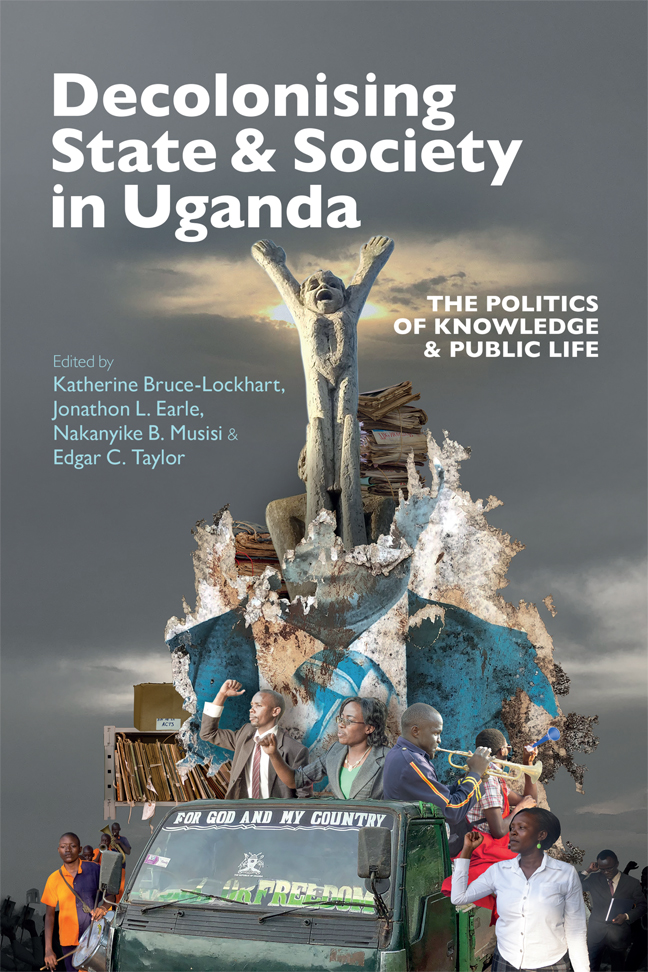

Decolonising State and Society in Uganda

- The Politics of Knowledge and Public Life

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 15 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 13 December 2022

Figures

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of the Aztecs

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp viii-ix

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Preface

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of the Aztecs

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp xiii-xxiv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Key Periods and Dates

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of the Aztecs

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp xxv-xxvi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Glossary

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of the Aztecs

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp 285-293

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Living in the Aztecs’ Cosmos

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of the Aztecs

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp 38-80

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of the Aztecs

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Tables

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of the Aztecs

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp xi-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Introduction

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of the Aztecs

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp 1-37

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bibliographic Essay

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of the Aztecs

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp 294-351

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of the Aztecs

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of the Aztecs

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Communities, Kingdoms, “Empires”

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of the Aztecs

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp 81-120

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Maps

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of the Aztecs

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp x-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Resilience

-

- Book:

- A Concise History of the Aztecs

- Published online:

- 08 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 15 February 2024, pp 202-245

-

- Chapter

- Export citation