Previous normative studies of emotional valence and arousal

Affective states are commonly defined by three dimensions—emotional valence, arousal, and dominance. Emotional valence represents our evaluation of the degree to which a stimulus is positive or negative (pleasant or unpleasant). On the other hand, arousal represents the degree to which we experience a stimulus as exciting or relaxing, and dominance refers to the controllability over the stimuli (Kuperman et al., Reference Kuperman, Estes, Brysbaert and Warriner2014; Russell & Mehrabian, Reference Russell and Mehrabian1977). However, in the literature, the dimensions that researchers primarily refer to are the first two: emotional valence and arousal. Theoretically, these two dimensions are orthogonal, or independent (Colibazzi et al., Reference Colibazzi, Posner, Wang, Gorman, Gerber, Yu, Zhu, Kangarlu, Duan, Russell and Peterson2010; Posner et al., Reference Posner, Russell and Peterson2005; Russell & Mehrabian, Reference Russell and Mehrabian1977), but empirical patterns show that the words are not equally distributed across this space. Within the space of these two dimensions, stimuli may have lower (more negative) valence and higher arousal, for example, “war,” but also may have higher (more positive) valence and higher arousal, as in the case of the word “happiness” (Russell & Mehrabian, Reference Russell and Mehrabian1977). Neutral stimuli lie towards the middle of the emotional valence dimension, but on the lower end of the arousal scale, for example, “analysis.”

A few decades ago, researchers recognized the importance of conducting normative studies and collecting a wide variety of psycholinguistic variables for large word samples (i.e., the Big data approach; Keuleers & Balota, Reference Keuleers and Balota2015). Having large norm databases is crucial for running different kinds of cognitive studies, not only within the area of psycholinguistics but also for research in domains like memory, decision-making, attention, and similar. All research that utilizes words is in need of various psycholinguistic descriptions of words in order to control for different stimuli features.

One conclusion that could be drawn from most of the norming studies that focused on words’ affective norms concerns the relation between emotional valence and arousal ratings. Most of these norming studies reported that the valence-arousal relationship could be described via the quadratic function or the U-shaped function, meaning that positively and negatively valenced words tend to be more arousing compared to neutral words (Bradley & Lang, Reference Bradley and Lang1999; Kanske & Kotz, Reference Kanske and Kotz2010; Moors et al., Reference Moors, De Houwer, Hermans, Wanmaker, van Schie, Van Harmelen, De Schryver, De Winne and Brysbaert2013; Planchuelo et al., Reference Planchuelo, Baciero, Hinojosa, Perea and Duñabeitia2022; Redondo et al., Reference Redondo, Fraga, Padrón and Comesaña2007; Warriner et al., Reference Warriner, Kuperman and Brysbaert2013). Moreover, such a relationship is found not just for lexical, but also for pictorial stimuli, such as emoticons (Kutsuzawa et al., Reference Kutsuzawa, Umemura, Eto and Kobayashi2022).

Many normative studies addressed the reliability of ratings by comparing the ratings of emotional valence and arousal in terms of the correlation between the two points in time (Kyröläinen et al., Reference Kyröläinen, Luke, Libben and Kuperman2021; Delatorre et al., Reference Delatorre, Salguero, León and Tapscott2019; López-Carral et al., Reference López-Carral, Grechuta and Verschure2020; Popović Stijačić, Reference Popović Stijačić2021; Stadthagen-Gonzales et al., Reference Stadthagen-Gonzalez, Imbault, Pérez Sánchez and Brysbaert2017). Ćoso et al. (Reference Ćoso, Guasch, Ferré and Hinojosa2019) did not have the data for the Croatian, so they validated their measurements with the Spanish and English norming studies. In both cases, the correlations were higher for emotional valence ratings than for arousal. Table 1 shows correlations between the data collected at two points in time within normative studies for valence and arousal of words and faces. The emotional valence showed higher correlations (ranging from 0.83 to 0.98) compared to the arousal (ranging from 0.53 to 0.76) and consequently more stability. This property of emotional valence is characteristic of both words and facial stimuli.

Table 1. List of studies comparing the ratings of emotional valence and arousal from different normative studies

Note: The list of normative studies is not exhaustive. N—The number of matching words; r—correlation between ratings from two normative studies.

Correlations between different measurement points reported in Table 1 indicate that emotional valence ratings are more stable than arousal ratings, regardless of the stimuli type. However, correlations themselves reveal nothing about the factors that could be the source of arousal variation. Several studies posed this question (Delatorre et al., Reference Delatorre, Salguero, León and Tapscott2019; Hristova & Grinberg, Reference Hristova, Grinberg, Bassis, Esposito and Morabito2015; Teismann et al., Reference Teismann, Kissler and Berger2020) and tried to explore contextual variables as possible influential factors.

Contextual factors influencing the emotional valence and arousal ratings

Not many studies directly manipulated the situational factors to explore the influence on emotional valence and arousal, so we reported the studies that used facial stimuli, not just words. For instance, Hristova and Grinberg (Reference Hristova, Grinberg, Bassis, Esposito and Morabito2015) explored the difference in emotional valence ratings of negative, positive, and neutral facial expressions after induction of a sad, happy, or neutral mood. Participants first watched different video clips, which served as mood inductors and then rated the mood of different facial expressions presented in photographs. The authors did not find a significant interaction between the mood and emotion of a face. In other words, they did not record the mood congruency effect. The authors found that participants had a tendency to give higher emotional valence regardless of the polarity of faces after the induction, either of happy or sad moods. Hristova and Grinberg (Reference Hristova, Grinberg, Bassis, Esposito and Morabito2015) concluded valence ratings are influenced by arousal related to the induced mood since the neutral condition did not provoke changes in valence ratings of faces. However, arousal was not a concern of their study, so it was measured neither for the facial expressions nor the video clips.

One study examined how imagining a scene of suspense affected the evaluation of words’ emotional valence and arousal (Delatorre et al., Reference Delatorre, Salguero, León and Tapscott2019), then compared these estimates with the norming study from Redondo et al. (Reference Redondo, Fraga, Padrón and Comesaña2007). The average new ratings of emotional valence and arousal were significantly lower than those from earlier research. The authors (Delatorre et al., Reference Delatorre, Salguero, León and Tapscott2019) found that when the suspenseful context is introduced, the participants tend to rate positive words less favorable than in the usual context. Furthermore, under the same context, words evoked smaller arousal ratings in participants, regardless of their valence, that is, words seemed more neutral than in “normal” context ratings.

In another study, Teismann et al. (Reference Teismann, Kissler and Berger2020) investigated how mood affects assessing emotional valence and arousal of words. In this research, participants were tested on anxiety and depression and rated a multitude of words on arousal and valence scales. The authors did not find that more depressed respondents gave different estimates for these two dimensions than those with a lower level of depression. On the other hand, those with a higher level of anxiety tended to give higher arousal estimates for neutral words, suggesting a relationship between anxiety and arousal.

A few papers published recently focused more on the contextual influence of the COVID-19 pandemic and worldwide lockdowns on the emotional valence and arousal ratings of words. López-Carral et al. (Reference López-Carral, Grechuta and Verschure2020) collected emotional valence and arousal estimates of facial stimuli during the lockdown and compared them with the estimates from Kurdi et al. (Reference Kurdi, Lozano and Banaji2017) norming study. Significantly higher valence estimates were observed for neutral and positively rated images compared to the previous study. However, although arousal estimates were numerically lower for neutral images, the differences were not statistically significant. In the language domain, Kyröläinen et al. (Reference Kyröläinen, Luke, Libben and Kuperman2021) investigated the effects of age and the pandemic on emotional valence ratings. Older participants tended to give higher valence estimates than younger participants, particularly during the pandemic. The authors interpreted these results as evidence that older participants are more resilient to the situational stressors caused by the pandemic.

Planchuelo et al. (Reference Planchuelo, Baciero, Hinojosa, Perea and Duñabeitia2022) gathered emotional valence and arousal ratings for COVID-related (hospital) and COVID-unrelated words (whale) during the period of the lockdown in Spain (from March until May 2020). Compared to Stadthagen-Gonzales et al. (Reference Stadthagen-Gonzalez, Imbault, Pérez Sánchez and Brysbaert2017) arousal ratings collected during COVID were lower overall. However, the authors recorded arousal ratings for COVID-related terms were higher than for COVID-unrelated terms. On the contrary, although the emotional valence ratings were lower in the COVID period, the ratings, on average, were more positive for COVID-related positive words (kiss, hug) than for COVID-unrelated positive terms. There were no differences in ratings of emotional valence for COVID-related negative words (medication, fear).

The authors interpreted the increase in valence ratings for COVID-related positive words as a “nostalgia boosting effect” (Planchuelo et al., Reference Planchuelo, Baciero, Hinojosa, Perea and Duñabeitia2022, p. 6). This effect means that participants in the absence of usual social contact, which includes body interaction with other people, gave higher estimates for words related to social interaction (such as kiss and hug). On the other hand, lower arousal ratings for words were in accordance with “pandemic fatigue” (Rudroff et al., Reference Rudroff, Fietsam, Deters, Bryant and Kamholz2020). According to Rudroff et al. (Reference Rudroff, Fietsam, Deters, Bryant and Kamholz2020), post-COVID fatigue is not caused only by the coronavirus disease, and it could be a consequence of psychological factors, like stress, anxiety, depression, and fear, that were common mental health issues during the pandemic. Authors (Planchuelo et al., Reference Planchuelo, Baciero, Hinojosa, Perea and Duñabeitia2022) concluded that the COVID-19 pandemic could be a relevant contextual factor influencing mental health and, therefore, emotional representations of words.

Our goal

The motivation for this research came from the new situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and total closure as one of the measures to combat the pandemic. Mental health research revealed that restriction of movement and previous freedoms, a consequence of the coronavirus was very stressful for the entire population (Damnjanović et al., Reference Damnjanović, Ilić, Lep and Teovanović2020; Marchini et al., Reference Marchini, Zaurino, Bouziotis, Brondino, Delvenne and Delhaye2021; Morales-Rodríguez et al., Reference Morales-Rodríguez, Martínez-Ramón, Méndez and Ruiz-Esteban2021; Rudroff et al., Reference Rudroff, Fietsam, Deters, Bryant and Kamholz2020; Sadiković et al., Reference Sadiković, Branovački, Oljača, Mitrović, Pajić and Smederevac2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Di, Ye and Wei2021). A recent Serbian study (Sadiković et al., Reference Sadiković, Branovački, Oljača, Mitrović, Pajić and Smederevac2020), in which participants reported their emotional state of fear, anxiety, anger, and boredom, found that the fear and anxiety were at their peak at the beginning of the lockdown and that the level of slowly decreased after five weeks. Considering that previous studies showed that mental state (Teismann et al., Reference Teismann, Kissler and Berger2020) or mood induction (Delatorre et al., Reference Delatorre, Salguero, León and Tapscott2019) influenced valence and arousal ratings, we assumed that changes in mental functioning during the pandemic could be caused by the change in valence and arousal ratings of words. One up-to-date study dealing with this issue (Planchuelo et al., Reference Planchuelo, Baciero, Hinojosa, Perea and Duñabeitia2022) found that the pandemic influenced both dimensions. COVID-related pleasant terms were estimated as more positive during the pandemic. Furthermore, although the arousal ratings were lower in general, during COVID-19, COVID-related words were rated as more arousing. Lower estimates of arousal during the pandemic are in line with Delatorre et al. study (Reference Delatorre, Salguero, León and Tapscott2019). However, the changes in the valence estimates are inconsistent across studies. One possible explanation could be the cultural differences (Kuppens et al., Reference Kuppens, Tuerlinckx, Yik, Koval, Coosemans, Zeng and Russell2017) and language differences (Ćoso et al., Reference Ćoso, Guasch, Ferré and Hinojosa2019). For instance, Kuppens et al. (Reference Kuppens, Tuerlinckx, Yik, Koval, Coosemans, Zeng and Russell2017) found that the U shape of the emotional valence and arousal relationship is universal across Western and Eastern cultures. However, this U shape steepness varied in that it was primarily evident in Canada (Western culture) and almost absent in China (Eastern culture). Thus, in Eastern countries, Emotional valence and Arousal are almost independent dimensions. Concerning the language differences, Ćoso et al. (Reference Ćoso, Guasch, Ferré and Hinojosa2019) hypothesized that possible variation in the processing and comprehension of different valenced words could be attributed to the specificity of Eastern Slavic languages (e.g., Croatian, Serbian, Polish) in the sense of their orthography, use of double negations, number of cases and similar. Therefore, we still do not have a full understanding of the effects of adverse context on the affective dimension of word meaning.

In order to fill the knowledge gap, our study aimed to explore the sensibility of emotional valence and arousal of words on situational factors, like was COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, we set two goals. The first was to collect ratings of emotional valence and arousal of words during the lockdown and after the end of such restrictive anti-pandemic public health measures. The second goal was to compare these ratings with the norms collected in the pre-pandemic period.

Method

Data were compared at three time points: before the COVID-19 pandemic in 2018 (the first time point), during the onset of the pandemic and the lockdown in Serbia in 2020 (the second time point), and during 2022 (the third time point) after government measures were abandoned. Data from the first sample were taken from Popović Stijačić (Reference Popović Stijačić2021) norms while data for the other two time points were collected specifically for the purposes of this paper.

Participants

The first time point in the data collection was represented by a selection from the Popović Stijačić (Reference Popović Stijačić2021) dataset collected in 2018. For the second and third time point, 42 and 100 participants, respectively, completed the questionnaire. The sample collected at the second time point consisted of undergraduate psychology students from the Department of Psychology, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Novi Sad (M age = 19.56, SD = 0.59; 86% female), whereas the sample collected at the third time point consisted of volunteers that responded to an online ad distributed through Facebook (M age = 41.7, SD = 8; 86% female). Data collection for the second time point lasted between late March 2020 (March 28th) and mid-April 2020 (April 15th) and for the third time point, data collection lasted between late July 2022 (July 25th) and mid-August 2022 (August 13th). All participants read an informed consent form before taking part in the study. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Belgrade.

Materials and design

The number of words presented to participants varied across three data collection points: 2100 words were rated at the first point, 803 at the second time point, and 882 at the third. The main sample for this study consisted of 803 words that were repeated across the three time points (Table 3). The word sample of all 882 words is described in Table 2 on a number of standard lexical variables.

Table 2. The descriptive measures for the 882 words that were presented during the data collection for the second and the third time points

Note. All ratings from Author (2021), with the exception of word frequency which was sourced from Kostić (Reference Kostić1999).

Table 3. The descriptive measures for the 802 words that were repeated across the three data collection time points

In the selection process, we started from the initial database of 2100 Serbian nouns that we had at our disposal (Popović Stijačić, Reference Popović Stijačić2021) and continued by selecting words with lower concreteness ratings (M≤4, from the range from 1 to 7). In doing so, we relied on the finding that emotions play a more significant role in the case of abstract, as compared to concrete words (Kousta et al., Reference Kousta, Vigliocco, Vinson, Andrews and Campo2011; Vigliocco et al., Reference Vigliocco, Meteyard, Andrews and Kousta2009). For instance, Vigliocco et al. (Reference Vigliocco, Meteyard, Andrews and Kousta2009) proposed that abstract words rely more on affective experiential information. Thus, we assumed that changes in the representation of the words are more likely for abstract concepts. Consequently, we decided to select them since we were limited in available participants during the COVID-19 lockdown.

At the second time point, we randomly split 803 words into two lists, one contained 400 and the second 403 words, and for each list, we created two random orders, resulting in the four lists of words created in different Excel files. For each word, participants simultaneously rated emotional valence and arousal. The lists were distributed via email after the participants agreed to take part in the study. For the third time point, we separated the 882 words into two lists containing 438 and 444 words. Then, each of those lists was divided into two (214 and 224, 214 and 230 words respectively), and for each part, the scale that the word was rated on was rotated using a latin square design. Finally, participants were presented with four lists (List 1: 214 words emotional valence rating and 224 arousal rating; List 2: 214 words arousal rating and 224 emotional valence rating; List 3: 214 words emotional valence rating and 230 arousal rating; List 2: 214 words arousal rating and 230 emotional valence rating) to which they were assigned randomly. Each participant was assigned to only one list. For the last time point, data were collected using the SoSci survey platform version 3.3.10 (Leiner, Reference Leiner2021).

Procedure

Words were presented on the computer screen, and each participant had to provide ratings on an emotional valence scale and arousal scale. At the first two data collection time points, participants were rating words on both scales, whereas in the third time point, due to technical limitations of the used platform, each participant rated the words on just one of the two scales. At the first and the second time points, the total of the presented words was split into smaller batches that were presented to participants. In the third one, lists were counterbalanced to ensure an approximately equal number of ratings per word on both scales. Hence, each word was rated by 17 to 27 participants in three time points. The number of ratings varied based on random assignment to the word list and the familiarity of the words to the participant rating them since it was possible to select the option “I am not familiar with this word.”

For both scales we used a 7-point Likert scale (Moors et al., Reference Moors, De Houwer, Hermans, Wanmaker, van Schie, Van Harmelen, De Schryver, De Winne and Brysbaert2013), however, the emotional valence and arousal scales differed in the value interpretation. For emotional valence, extremes of the bipolar scale represented negative (1) and positive (7) words. The middle point (3) represented neutral words, not regarded as either positive or negative. On the other hand, arousal was rated on a unipolar scale, where low extreme represented words low in arousal, and high extreme highly arousing words.

At the beginning of the procedure, participants read the informed consent form and then were instructed on the rating procedure for emotional valence and arousal scales. Instructions contained examples of words that might be rated on the extreme of the scales. Participants then went on to rate each word on one or both scales. The third data collection time point was followed by some additional questions that are not within the scope of this paper.

Analysis strategy

We conducted the analyses in several steps. 1) We will first present the detailed descriptive by-item statistics across the three measuring points in time (pre-COVID-19, during COVID-19, and post-COVID-19). Within this segment, we will first investigate the stability of the ratings across time: for arousal and emotional valence separately, we will compare the ratings across the three points in time by inspecting their distributions and the bivariate correlation. We will then focus on the relationship between arousal and emotional valence ratings at three points in time. 2) In the next step, we will conduct inferential statistical analyses to investigate whether the changes observed based on the descriptive statistics are significant. We will start by applying Gradient Boosting Machines (Friedman, Reference Friedman2001) to deal with collinearity and select the best candidates for the predictors. We will then build a General Additive Model (Wood, Reference Wood2006, Reference Wood2011) to test the significance of the selected predictors, namely to test whether the change in the relation between valence (the predictor) and arousal (the criterion variable) was significant. To make the change more visible we will present the results by splitting the dataset into three subsamples: negative, neutral, and positive valence words, and visually compare the three subsamples at three time points. 3) Finally, we will present the results of the descriptive analyses in which we investigated whether the observed change in the relationship between the arousal and the valence ratings was affected by the semantic/associative relatedness to COVID-19. We will do this in two steps. First, we will inspect the words that were selected by the three authors from the original database as being highly related to COVID-19 and intentionally included in the post-COVID-19 data collection. Finally, we will do the same for three time points for all the words (after splitting them into COVID-19-related and unrelated based on the ratings provided by the three authors).

Results

The data were analyzed in R statistical software (R version 4.0.5; R Core Team, 2021) by using dplyr (Wickham et al., Reference Wickham, François, Henry and Müller2022), ggplot2 (Wickham, Reference Wickham2016), gbm (Ridgeway et al., Reference Ridgeway2017), mgcv (Wood, Reference Wood2006, Reference Wood2011), and itsadug (van Rij et al., Reference van Rij, Wieling, Baayen and van Rijn2015) packages.

In the first step, upon aggregating at the by-item level, the main sample was created by selecting only the items that were repeated across the three data collection time points, and the descriptive measures were calculated for these words (Table 3).

Before the analysis, we conducted the reliability testing of the questionnaires. We calculated the interclass correlations (ICC; two-way random average ICCs) and the coefficient of variation among questionnaires (CV). The average ICCs were high both for emotional valence (0.87 – 0.97, ICC mean = 0.94, SD = 0.05; CV = 4.97%) and arousal (0.95 – 0.98, ICC mean = 0.97, SD = 0.02, CV = 1.75%). Due to high-reliability measures, no data trimming or cleaning was done prior to calculating average arousal and valence values. Concerning the validity, it was a part of the next analysis, where we correlated the obtained emotional valence and arousal ratings with those from 2018. Since we had the norms for the Serbian, we refer to it as the stability of the measures.

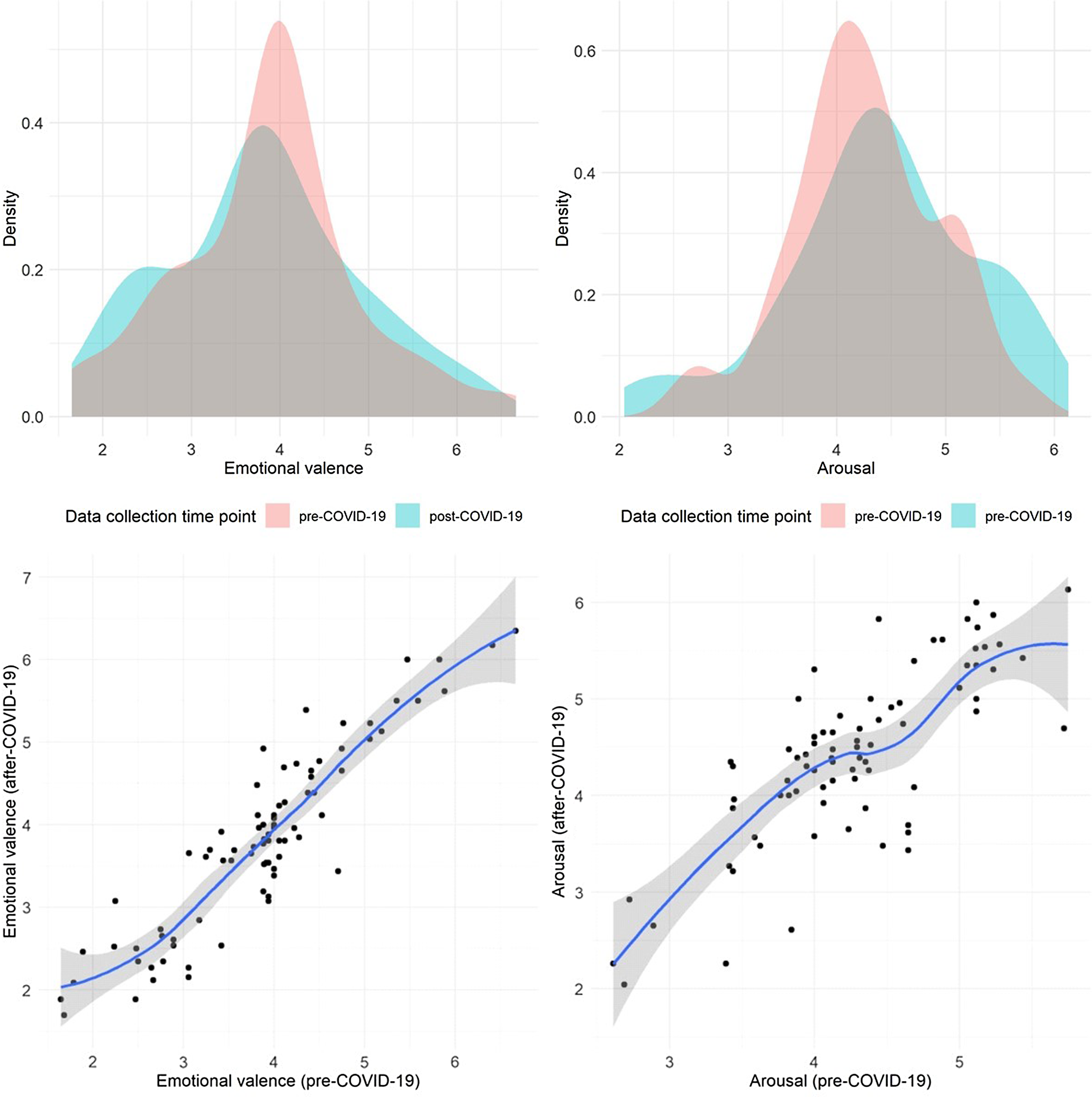

Our main interest was monitoring the change in valence and arousal ratings across the three testing phases. Therefore, we compared these variables across the three time points: pre-COVID-19, during COVID-19, and post-COVID-19. As can be observed in Table 3 and Fig. 1, there were virtually no changes in average valence ratings and only a slight numerical increase in arousal ratings in the post-COVID-19 testing. The observed pattern of valence data is confirmed by investigating bivariate correlation coefficients between pre-COVID-19 valence ratings and valence ratings collected during COVID-19 (r = 0.928, t(800) = 70.408, p < 0.001) and also between pre-COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 valence ratings (r = 0.898, t(800) = 57.534, p < 0.001). However, the same analysis revealed lower bivariate correlation coefficients in the case of arousal. Although the observed correlations were again positive and high, their values were somewhat lower both in the case of pre-COVID-19 arousal ratings and arousal ratings collected during COVID-19 (r = 0.756, t(800) = 32.673, p < 0.001), and also between pre-COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 arousal ratings (r = 0.704, t(800) = 28.034, p < 0.001). Therefore, we concluded that although valence remained stable across the three points in time in our dataset, the arousal ratings showed a tendency toward being less consistent.

Figure 1. The emotional valence and arousal distributions and their correlations across the three data collection time points.

Note. Top row: the comparison of the valence (left) and arousal (right) rating distributions across the three data collection time points (pre-COVID-19, during COVID-19, and post-COVID-19). Bottom row: correlation between pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19, and between pre-COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 ratings of valence (left) and arousal (right).

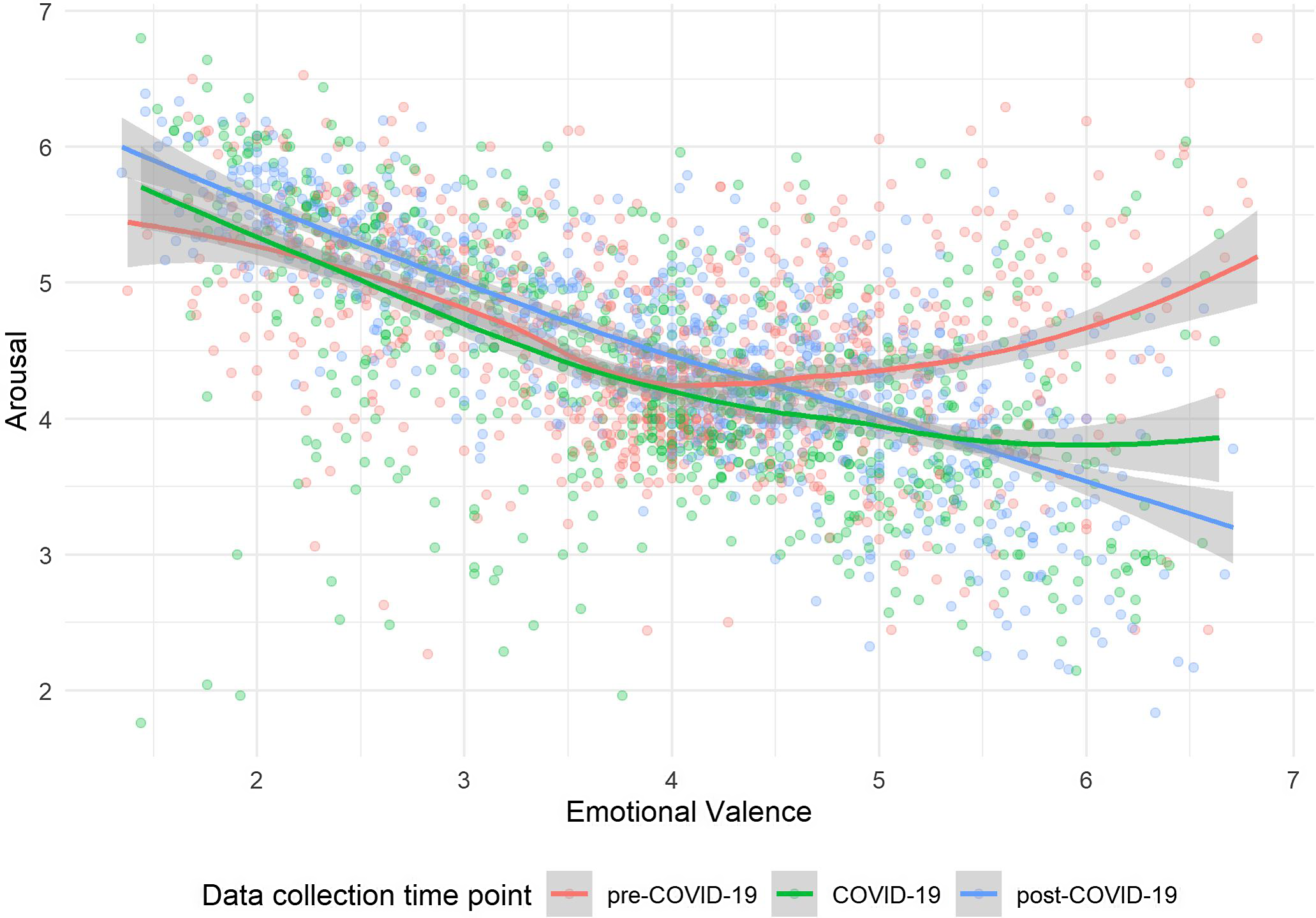

In order to investigate the change in arousal ratings across time in more detail, we turned to the relation between valence and arousal. As illustrated in Fig. 2, at the first time point, that is, pre-COVID-19 testing, we observed a typical U-shaped relation between the two variables (green line), as also reflected in the low bivariate correlation coefficient between the two (r = −0.286, t(800) = −8.452, p < 0.001). Behind this nonlinearity is the fact that typically words of negative valence are rated as the most arousing, followed by words of positive valence, whereas neutral words elicit the lowest arousal ratings. However, in our dataset, this pattern seemed to change across the three time conditions. During the COVID-19 lockdown (blue line), the bivariate correlation coefficient between valence and arousal was higher compared to pre-COVID-19 ratings (r = −0.545, t(800) = −18.404, p < 0.001), and the raising trend continued in the post-COVID-19 data collection time point (red line; r = −0.773, t(800) = −34.502, p < 0.001). The increase in bivariate correlation coefficient values is caused by the disappearance of the nonlinearity in the monitored relation (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2. The relation between emotional valence and arousal across the three data collection time points.

We wanted to explore whether the observed change in the relation between valence and arousal across the three data collection time points was significant. Therefore, we turned to statistical modeling and built a regression model with arousal as the dependent variable. In order to select the relevant predictors, we applied Gradient Boosting Machines, which suggested that the best predictors of arousal would be valence, context availability, familiarity, and testing phase (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. The relative importance of variables in predicting arousal ratings.

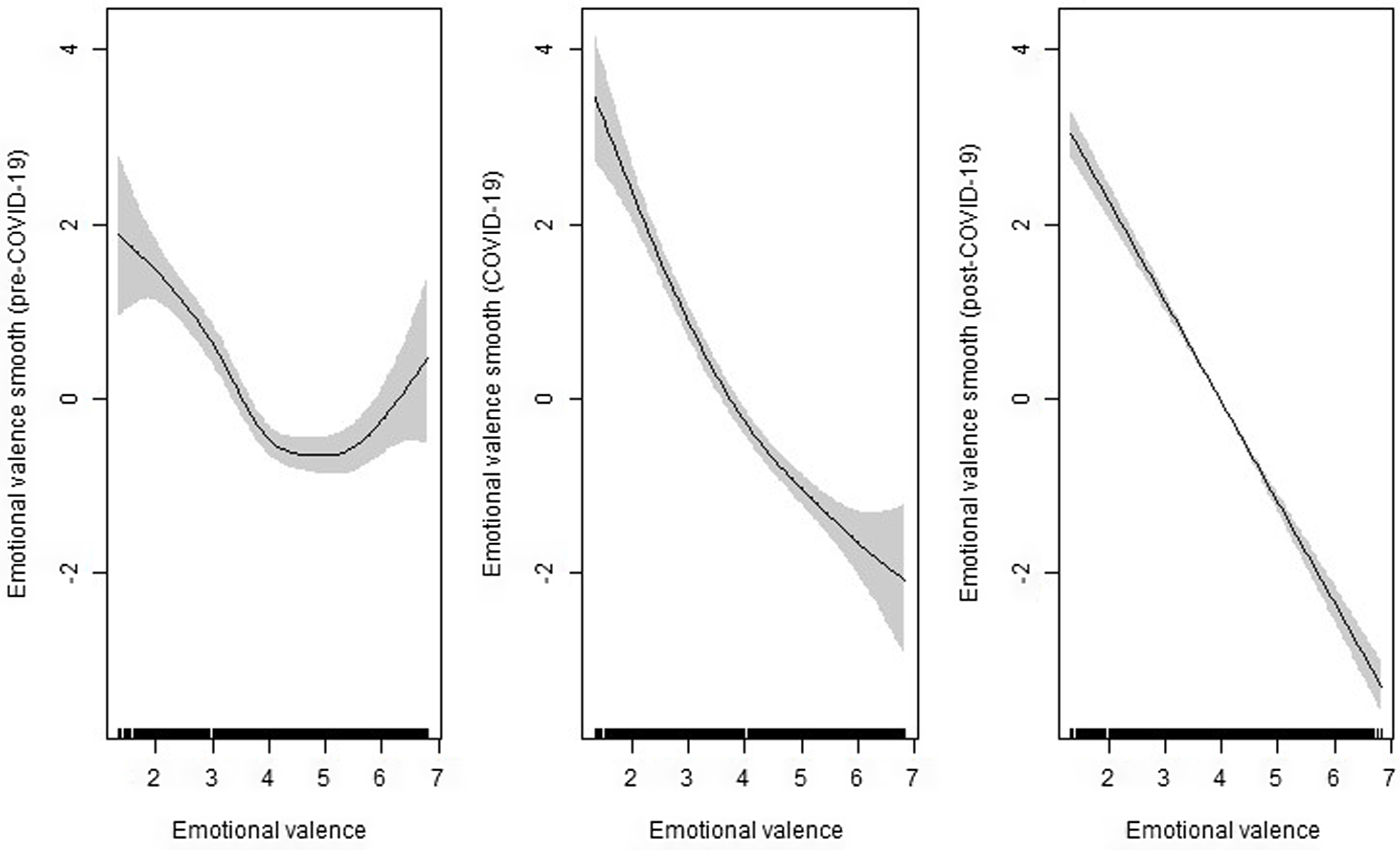

In the next step, we built a General Additive Mixed Model (Table 4) to investigate whether the change in nonlinearity was significant across the three time conditions. Our analyses confirmed that the relation between valence and arousal differed across pre-COVID-19, during COVID-19, and post-COVID-19 conditions. As depicted in Fig. 4, the nonlinear relation that was present in the pre-COVID-19 testing, was less expressed in the testing during COVID-19, and almost completely disappeared in the post-COVID-19 testing session, where the relation was linear. We found that the linearization was a consequence of a selective change in arousal ratings across sessions. The arousal ratings tended to increase for words of lower valence while decreasing for words of higher valence.

Figure 4. Partial effects of valence on arousal across the three time conditions: Pre-COVID-19, during COVID-19, and post-COVID-19.

Table 4. The coefficients from the general additive model fitting arousal ratings

Note. s()—parametric smooth; edf—effective degrees of freedom, Ref.df—reference degrees of freedom.

To shed even more light onto the observed change in arousal ratings, we split our dataset into three equally-sized subsamples according to values of valence ratings. Low values represent words of negative valence, mid-range is related to neutral words, and high values represent words of positive valence. As illustrated in Fig. 5, unlike arousal ratings of emotionally neutral words, which remained constant over time (except for the mild short-lived decrease during COVID-19), the ratings of emotionally charged words changed. However, this change was not the same for emotionally negative and emotionally positive words. The arousal by words of positive valence decreased during COVID-19 and remained on the same level in the post-COVID-19 period. On the other hand, the arousal by words of negative valence increased in the post-COVID-19 time.

Figure 5. Average arousal ratings across the three data collection time points for three groups of words (Negative, neutral, and positive).

COVID-19-related words

In order to test whether our findings would differ for words which are related to COVID-19 in meaning, we conducted similar analyses on the subset of 80 words that we explicitly rated as COVID-19-related and presented to our participants at the second time point of data collection. Therefore, these are the words for which we also have pre-COVID-19 ratings and post-COVID-19 ratings. As presented in Fig. 6, neither the emotional valence nor the arousal has changed in the post-COVID-19 data collection time point. Also, the pre-post-correlation for both arousal (r = 0.784, t(78) = 11.17, p < 0.001) and valence (r = 0.915, t(78) = 20.149, p < 0.001) is fully comparable to the words from the main sample.

Figure 6. The valence (left) and arousal (right) ratings distributions and for additional COVID-19-related words and their correlations.

Note. Top row: The comparison of the valence (left) and arousal (right) rating distributions for additional 80 COVID-19-related words, across the two data collection time points (pre-COVID-19, and post-COVID-19). Bottom row: Correlation between pre-COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 ratings of valence (left) and arousal (right) for the same set of words.

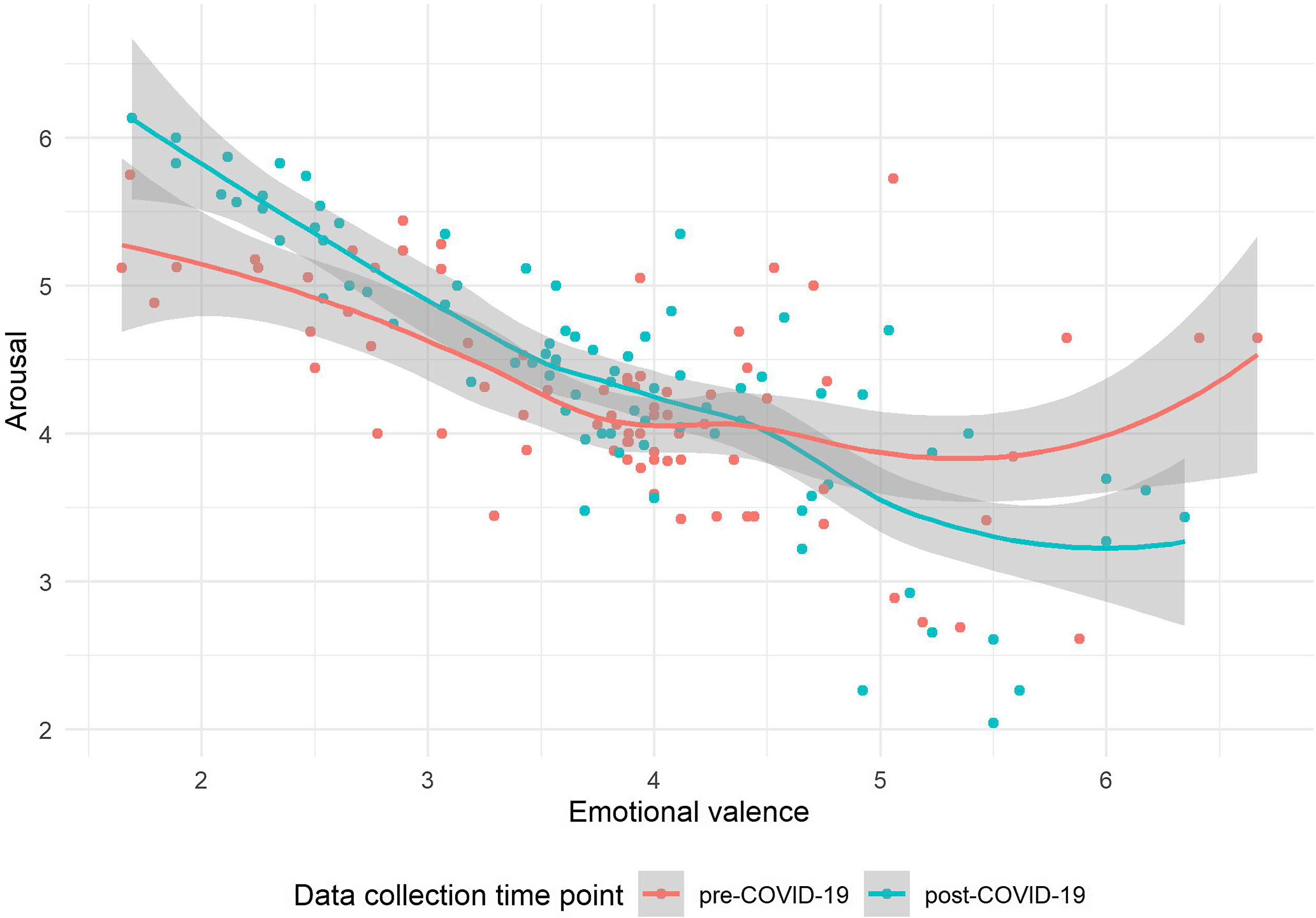

Next, in order to test whether the increase in arousal for negative words and the decrease in arousal for positive words are different for COVID-related words we looked into the bivariate correlation between emotional valence and arousal in two points in time. As presented in Fig. 7, COVID-related words reveal the same pattern as the words in the main sample. We, therefore, conclude that our findings are revealing of the words in general.

Figure 7. The relation between emotional valence and arousal of additional set of COVID-19-related words across the two points in time: Pre-COVID-19 (green) and post-COVID-19 (red).

Finally, the three co-authors independently rated the full set of 882 words on COVID-19 relatedness, marking them either related or unrelated to COVID-19. We then selected only those words for which the coders were unanimous in categorization. By doing this, we obtained a subsample of 151 COVID-19-related words and 359 words that were unrelated to COVID-19. As depicted in Fig. 8, the pattern of results that we have described in this paper (Fig. 2) is almost identical in two groups of items (COVID-19-related and COVID-19 unrelated words). Therefore, the selective change in arousal that we have observed across the three points in time is related to emotional valence and seems to be independent of relatedness to COVID-19.

Figure 8. The relation between emotional valence and arousal of COVID-19-related (left panel) and COVID-19-unrelated words (right panel) across the three data collection time points.

Discussion

Since the beginning of 2020, the world has faced the COVID-19 pandemic. Worldwide there were long-lasting lockdowns, limiting everyday life, daily movement, and face-to-face social interaction. The severe consequences of illness caused by the coronavirus, many losses of loved ones, lack of information or too much misinformation represented risk factors that elicited mental health issues, such as stress, anxiety, and depression (Damnjanović et al., Reference Damnjanović, Ilić, Lep and Teovanović2020; Rudroff et al., Reference Rudroff, Fietsam, Deters, Bryant and Kamholz2020; Sadiković et al., Reference Sadiković, Branovački, Oljača, Mitrović, Pajić and Smederevac2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Di, Ye and Wei2021). Several authors have questioned whether the COVID-19 pandemic could be a significant situational factor influencing, among other things emotional representations of words (Planchuelo et al., Reference Planchuelo, Baciero, Hinojosa, Perea and Duñabeitia2022). Therefore, in our study, we set two objectives: to collect the emotional valence and arousal ratings of words during and after the coronavirus pandemic and to compare them with the estimates collected before the pandemic.

We monitored valence and arousal ratings for a large set of Serbian words during the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. Using the pre-COVID-19 database as the starting point, we collected ratings during the lockdown in Serbia and two years later, at the point in time when the pandemic was settling down (we refer to this condition as the post-COVID-19). We found that valence did not change across the three conditions, whereas there were some important findings related to the arousal ratings. Although at the global sample, there were no dramatic changes, we observed important differences in the relation between valence and arousal across the three points in time. Our most important finding showed that while the arousal elicited by words of negative valence tended to increase over difficult times, the arousal elicited by words of positive valence tended to decrease. This pattern was the same for COVID-19-related and COVID-19-unrelated words, revealing that our evaluation of the words remains constant regardless of the content, over time and under a significant change in the situational factors, but the potential of the arousal of the words changes.

Our novel finding is in accordance with the results reported in a recent paper by Delatorre and colleagues (Reference Delatorre, Salguero, León and Tapscott2019). In their study, the authors investigated the effect of context on affective ratings and found the tendency of arousal ratings to decrease in times of suspense. However, unlike their study, which used artificially induced context, ours was conducted in a real-life context. A similar study conducted during the COVID-19 lockdown in Spain recorded lower arousal estimates (Planchuelo et al., Reference Planchuelo, Baciero, Hinojosa, Perea and Duñabeitia2022) but did not cross it with valence ratings but instead with word’s relatedness with COVID-19. Consequently, we do not know the valence of those COVID-related terms. To the best of our knowledge, no other study observed differential change in arousal depending on the valence of words (the overall arousal level in our study remained constant during the lockdown and two years later).

Rudroff et al. (Reference Rudroff, Fietsam, Deters, Bryant and Kamholz2020) proposed the “pandemic fatigue” hypothesis to account for the decrease in arousal levels. They hypothesized that the stress induced by the pandemic was at the root of this finding. Our results related to the decrease in arousal ratings of positive words fit with the post-COVID fatigue hypothesis (Planchuelo et al., Reference Planchuelo, Baciero, Hinojosa, Perea and Duñabeitia2022). However, unlike the studies of Rudroff et al. (Reference Rudroff, Fietsam, Deters, Bryant and Kamholz2020) and Planchuelo et al. (Reference Planchuelo, Baciero, Hinojosa, Perea and Duñabeitia2022) that were conducted only during the lockdown, our study also spanned the time when none of the anti-COVID regulations were in place. Moreover, the data at the third time point were collected during the summer vacations—a typical time of relaxation. In spite of that, the COVID-19-induced change in arousal persevered, suggesting prolonged post-COVID fatigue. Alternatively, the sustained drop in arousal estimates for positively valenced words may be due to the newly emerged crises in 2022 (war in Ukraine, economic crisis). Besides the post-COVID fatigue as an explanation for the lower arousal of positively valenced words, there is no explanation provided by previous studies for the arousal increase for the negatively valenced ones in the third time point. We hypothesized that continuous exposure of people to catastrophic news might have led to even more significant bias toward negative stimuli. This scenario is justified as Karademas et al. (Reference Karademas, Kafetsios and Sideridis2007) found that lower optimism is associated with a greater bias toward negative stimuli. Similar results were recorded in Segerstrom’s (Reference Segerstrom2001) study. She found that participants with higher optimism (more positive outcome expectations) had attentional bias (measured by emotional Stroop task and skin conductance response) toward negatively and positively valenced words. On the contrary, those with higher pessimism had an attentional bias only towards negatively valenced words. She concluded that attentional bias towards negative or threatening stimuli is adaptive because we need to avoid or face a dangerous situation. On the other hand, individuals with negative outcome expectancies are more focused on such stimuli.

Our and many other studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic suggest that people behaved differently, had stronger emotional reactions, and felt more distressed compared to the period before or after the pandemic (Damnjanović et al., Reference Damnjanović, Ilić, Lep and Teovanović2020; Marchini et al., Reference Marchini, Zaurino, Bouziotis, Brondino, Delvenne and Delhaye2021; Morales-Rodríguez et al., Reference Morales-Rodríguez, Martínez-Ramón, Méndez and Ruiz-Esteban2021; Rudroff et al., Reference Rudroff, Fietsam, Deters, Bryant and Kamholz2020; Sadiković et al., Reference Sadiković, Branovački, Oljača, Mitrović, Pajić and Smederevac2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Di, Ye and Wei2021). According to Levine (Reference Levine2003), natural disasters and war are in the top ten social factors that promote vulnerability, that is, adverse environmental factors for resilience.

What should note regarding the results of this study that, although the same words were rated across three time points, data collection methods varied largely. Data for the first time point were collected as a part of the larger norming study (Popović Stijačić, Reference Popović Stijačić2021). Second and third time points differed in the number of words (the second time point having roughly 10% less stimuli than the third one) and the split of the total words into word lists to reduce the number of ratings per participant and due to some technical limitations. At the second time point, each participant rated a subset of words on both scales, and at the third time point, each subset that the participant rated was split further and each of those halves was rated on a single rating scale. This meant that two different scales were once rated by the same person, and another time by different people. This could affect the correlations, however, the linearization of the emotional valence–arousal correlation occurred between the first and the second time point. The third time point followed the trend; however, we must note that at least some differences in variance could be the consequence of methodology, rather than even more pronounced change in arousal. Finally, the main task for the participants was exactly the same and they were instructed in exactly the same way (instructions taken from Popović Stijačić, Reference Popović Stijačić2021), therefore should not affect the emotional valence and arousal estimations severely. Another methodological limitation is the cross-sectional design that this study employs. However, not being able to keep the design fully longitudinal, due to the sudden nature of the pandemic, measurements comparison remained between subjects. Nonetheless, both previous studies presented in Table 1 and correlations between our three time points point to high correlations between repeated measurements of both emotional valence and arousal.

Our data fit into all previous studies, which supported the idea that valence and arousal could change independently, especially in the findings of Kuppens et al. (Reference Kuppens, Tuerlinckx, Yik, Koval, Coosemans, Zeng and Russell2017). They found that although dominantly represented by U shape, the relationship between emotional valence and arousal is also a function of individual and cultural differences. Our research and previous findings (Delatorre et al., Reference Delatorre, Salguero, León and Tapscott2019; Planchuelo et al., Reference Planchuelo, Baciero, Hinojosa, Perea and Duñabeitia2022) show that this relationship also changes due to social and environmental factors. Our data suggests that times of crisis increase our potential to react to negatively charged words, while at the same time decreasing our potential to react to positively charged words. In other words, not only are we more sensitive to negative content but we also lose the potential to be revived by positive content.

From a technical point of view, our data advise caution when using or collecting norming data. Unlike valence which can be used without restrictions, the norming data on arousal should be used with caution. A potential diagnostic tool for the validity of arousal data can be the signature U-shaped relation with valence.

Finally, our findings open the door for potential investigations of the effect of contextual factors on other lexical-semantic variables that are typically used in psycholinguistic research.

Replication package

All the data, R codes and materials are fully available on the OSF platform site at https://osf.io/cfq8n/.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank all the participants that were involved in the study.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Ksenija Mišić, Milica Popović Stijačić, and Dušica Filipović Đurđević. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Milica Popović Stijačić (introduction and discussion), Ksenija Mišić (method and results), and Dušica Filipović Đurđević (results and discussion). All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

This research was partially funded by the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Belgrade (grant: “Humans and Society in Times of Crisis”) and by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia (grant numbers 179033, 179006).

Competing interests

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Department of Psychology, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Belgrade, and certify that the study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to participate

The consent to participate was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

All participants signed informed consent which included consent for publication.