Introduction

More than 30 countries possess electoral laws that offer select ethnic groups a minimum number of political representatives in national parliament. At least ostensibly, these laws assist ethnic minorities in protecting and/or advancing their own interests, while also gaining a share of power within the state (Kymlicka Reference Kymlicka1995; Krook and O’Brien Reference Krook and O’Brien2010; Bird Reference Bird2014; Zuber Reference Zuber2015). Countries with these laws are quite geopolitically diverse; they include Bolivia, Denmark, India, Fiji, Niger, Palestine, Singapore, and many others. The ethnic representatives, who hold positions in government, are expected to protect the interests of the minority populations they represent (Zuber Reference Zuber2015). Regarding these systems, there exists a growing empirical literature, particularly regarding contemporary reserved seats and proportional representation systems (Reynolds Reference Reynolds2005; King and Marian Reference King and Marian2012; Protsyk Reference Protsyk2010b; Lublin and Wright Reference Lublin and Wright2013; Bird Reference Bird2014; Zuber Reference Zuber2015; Kroeber Reference Kroeber2017). This scholarship has done much to unpack how ethnic minority groups gain access to (or face barriers from) diverse states.

While this scholarship has provided several compelling descriptive and critical accounts of the workings and shortcomings of minority representation systems, there does not exist as much analytical research on the topic. As a result, the existing scholarship remains largely under-theorized. This article attempts to build on the descriptive and empirical research by providing an analytical account of how countries with minority inclusion policies operate. In order to achieve this end, the analysis applies the theoretical frameworks of institutional activism and ethnic intermediation to a case study of the small yet influential Armenian minority in post-communist Romania.

Romania’s “minority regime,” which began after the fall of communism and continues to operate today, resulted, in part, from the institutional activism and ethnic intermediation of a cadre of well-positioned social activists, who would ultimately comprise a large part of Romania’s transitional government and write much of its draft constitution. Because several Romanian Members of Parliament (MPs) operate as both the leaders of ethnic organizations and deputies in parliament, Romania proved an ideal site in which to broaden the framework of ethnic intermediation, which typically unpacks power cleavages among large, disenfranchised minority or immigrant groups strictly inside or outside of the state. Drawing from over 30 in-depth interviews and extensive participant observation, this article analyzes how ethnic activists in Romania’s transitional government helped create constitutional provisions, which have led to a distinct form of ethnic intermediation.

The analysis relies on a case study of the understudied yet influential Armenian community of Romania. Although quite small in number, Armenians have played an important role in Romania’s transitional and contemporary governments. For example, some Romanian Armenians helped draft the constitutional provisions regarding national minorities. In addition, the only two people who have served as the deputy of the minorities parliamentary group have been Armenian. While Armenians are only one of several ethnic communities that participated in Romania’s post-communist transition government and in restructuring the governmental institutions, they exemplify how small yet well-integrated ethnic minority activists and intermediaries restructure post-communist state institutions.

Systems of Minority Representation

Proportional representation (PR) and reserved seats are two systems, which several countries employ to increase minority representation in government. These are not novel approaches. In the nineteenth century, John Stuart Mills, particularly concerned with the potential for majoritarian tyranny in democratic systems of representation, advocated a particular system of PR.Footnote 1 The advocacy of Mills and others for PR ultimately spread throughout the British Empire and beyond. In addition, twentieth century Anglophone colonial administrations used a reserved seat system in India, Kenya, South Africa, and Tanzania to prevent indigenous groups from gaining power (Reynolds Reference Reynolds2005). Reserved seats have also been used in efforts to mitigate interethnic conflicts in Cyprus, Fiji, Lebanon, Zimbabwe, and others (Lublin Reference Lublin2014).

Since both systems purportedly help minority or disenfranchised populations gain seats and influence legislation, there exists overlap between them. But there are some important distinctions, as well. Reserved seats electoral laws guarantee positions in legislature for small, select ethnic groups (or national minorities), which often have a long-standing history or a history of oppression in the country. In these contexts, representatives from the select groups are elected separately from the state’s remaining representative body (Kroeber Reference Kroeber2017). Some countries that have adopted reserved seats policies include Cyprus, New Zealand, and Taiwan. On the other hand, PR or mixed systems require parties to secure a minimum threshold of votes to secure seats in parliament. In some geopolitical contexts, policies reduce the thresholds for designated minority groups or exempt them altogether. In countries with lower thresholds, small minorities gain parliamentary seats, which their small numbers would have otherwise made impossible. These PR or mixed systems with reduced thresholds are engineered to facilitate the success of designated minority groups (Lublin and Wright Reference Lublin and Wright2013). Some countries that have adopted PR policies include Denmark, Germany, and Italy. Similar to reserved seats, PR systems also often occur as a means to ensure small, dispersed minority groups can compensate their numerical disadvantages and gain legislative seats. But PR systems, distinct from reserved seats, typically require designated groups secure at least a minimal share of votes.

Romania’s System of Representation

Brief Background

During Romania’s transition out of communism, mounting interethnic tensions between Hungarians and Romanians erupted (Stan and Turcescu Reference Stan and Turcescu2007). International organizations (such as the Project on Ethnic Relations) as well as Romanians and Hungarians from the National Salvation Front (NSF) worked together to resolve these tensions. Many of those involved had no previous governmental experience (Grosescu Reference Grosescu2004). Among those new to politics was a combination of activists, writers, intellectuals, and other public figures.

In 1991, officials formed an interim parliament – the Provisional Council for National Unity (CPUN) – in response to anti-NSF protests. Minority groups played an important role in this transitional government: out of the 255 members of CPUN, 27 represented national minorities. During this period, the assembly produced a draft constitution, and many of its provisions were upheld in the establishment of Romania’s 1991 Constitution. These would, ultimately, include Romania’s constitutional provisions regarding national minorities. According to Article 6, the Romanian Constitution “guarantees the right of persons belonging to national minorities to the preservation, development and expression of their ethnic, cultural, linguistic and religious identity.” In addition, article 58 of the 1991 Romanian Constitution (now Article 62), states that “organizations of citizens belonging to national minorities, which fail to obtain the number of votes for representation in Parliament, have the right to one Deputy seat each, under the terms of the electoral law. Citizens of a national minority are entitled to be represented by one organization only.”Footnote 2 These articles introduced some of the most extensive seat provisions in Europe (Bird Reference Bird2014); in addition, they placed minority organizations in representative roles of legislature. CPUN’s transitional government thus initiated a period of ethnic legislative reform in post-communist Romania.

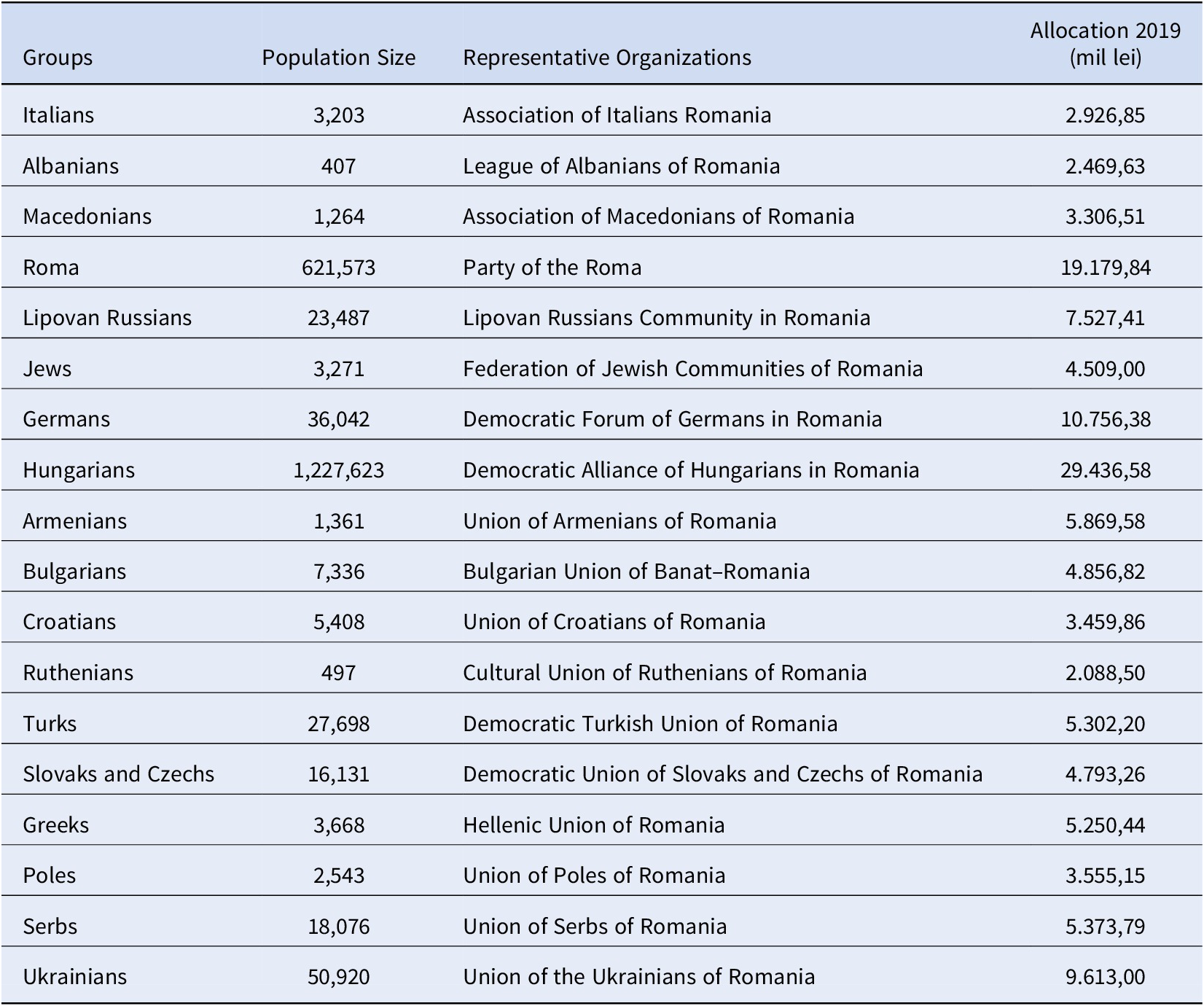

Following the transition, a “minority regime” would blossom with the drafting of nearly 600 different laws and decrees related to national minorities (Salat and Novak Reference Salat, Novák, Stan and Vancea2015, 76). These provisions brought Romania international attention. As Salat and Novak have pointed out, in 1992–93, Romania received the “Most Favored Nation Clause” from the U.S. Congress, gained entry to the Council of Europe, and signed an agreement of association with the European Union (2015, 74).Footnote 3 Also, in 1993, the government established an advisory body of all the minority organizations with elected representation in parliament. This body – the Council of National Minorities – could propose legislation or comment on draft bills and decrees, which related to minority groups in Romania. The Council also increased minority groups’ effectiveness in promoting relevant agendas and strengthened these groups’ influence in parliament. In practice, the Council largely proposes allocations of public subsidies among designated minorities. These allocations support minority organizations’ cultural and educational activities (King and Marian Reference King and Marian2012). At the time of this writing, there are 18 designated national minorities, which receive financial allocations from the government and seats in the Romanian Parliament. Table 1 lists Romania’s designated groups, their population sizes (according to 2010 census data), and their 2019 allocations. Taken as a whole, Romania’s “minority regime,” with its constitutional provisions, laws, decrees, and bodies, ensured a high level of political representation for many minority populations in Romania. In addition, the reforms helped signal to the international community that Romania had broken with its communist past and sought reunification with Europe.

Table 1. List of designated national minority groups, their population sizes, representative organizations, and state allocations (2019)

Nevertheless, Romania’s “minority regime” also involved the opportunism of several leading officials (Alionescu Reference Alionescu2004). While ethnic minorities and activists in post-communist Romania played integral roles in the transition, some officials most likely co-opted small minority groups in order to neutralize the largest Hungarian Romanian political party – the Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania (UDMR). As Table 1 reflects, the overrepresentation of small ethnic groups is salient. Apart from the Hungarians, the 17 remaining organizations each have a parliamentary vote and disproportionate per capita allocations. Because the system advantages small groups, it tends toward positive discrimination (King and Marian Reference King and Marian2012). And several CPUN officials most likely engineered this system of positive discrimination to gain support from the international community and weaken Hungarian political opposition.

Among those who approached the “minority regime” opportunistically were many second-ranked communist party members in the NSF. This group included Romania’s first post-communist president, Ion Iliescu. While the ethnic and social activists formed another large share of the CPUN, many in the NSF leadership – and, in particular, President Iliescu – very likely co-opted minority groups in an effort to consolidate and retain their loyalty. King and Marian (Reference King and Marian2012) argue that Romania’s distributive politics increase dependency on the state and entangle minority organizations in a network of the ruling elite; as a result, the system simultaneously incorporates and marginalizes ethnic groups (584). Indeed, apart from the UDMR, minority representatives rarely vote in opposition to the ruling party. As Karen Bird argues, “It is true that the UDMR deputies tend to vote in opposition, while ‘reserved seat’ MPs behave consistently as a staunch ally of any government in power and always vote as such” (Reference Bird2014, 20). To be sure, the opportunism of several actors during Romania’s transition does not negate the roles ethnic activists played and continue to play in post-communist Romania. Still, several NSF officials’ opportunism also factored significantly into the establishment of Romania’s post-communist “minority regime”; this opportunism continues to influence contemporary Romanian politics.

Classification

Because Romania’s policies allocate seats in parliament for designated national minority organizations, some scholars refer to this approach as a system of reserved seats (King and Marian Reference King and Marian2012). But ethnic minority organizations must also receive a reduced threshold of votes in order to gain their parliamentary seats. Romania’s electoral laws do not guarantee (or reserve) these parliamentary seats to the 18 designated groups; minority organization representatives must receive PR of five percent the number of votes compared to other political parties in the Chamber of Deputies in Romania’s lower house of parliament. As such, they can potentially lose their seats in parliament. This occurred in 2016, when internal conflict and competition among the Tatar population resulted in no single minority organization achieving the threshold. Since 2016, Tatar Romanians have been excluded from the list of designated national minorities and no longer receive financial support from the state.Footnote 4 Thus, the reduced electoral threshold and lack of a legal guarantee for existing minority organizations more closely resemble a system of PR rather than one of reserved seats (Reynolds Reference Reynolds2006; Protsyk Reference Protsyk2010b; Lublin and Wright Reference Lublin and Wright2013; Bird Reference Bird2014).

The Armenians of Romania

Armenians have a long, continuous history of inhabiting what Romanians consider their ancestral homelands. Among the first to arrive were traders and merchants in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. They settled in various parts of Moldova, and, through the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, spread into Wallachia and Bucharest. These communities prospered (Siekierski Reference Siekierski2011, 385).

In the seventeenth century, many Armenians relocated to Transylvania to escape religious persecution and improve their economic circumstances. In Transylvania, Armenians founded and built the community of Armenopolis (present day Gherla in Cluj County)Footnote 5 . Also in Transylvania, the Armenian bishop, Oxendius Verzerescu, adopted Roman Catholicism and founded the Armenian Catholic Church – a departure from the Armenian Apostolic Church. Through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries these scattered communities thrived, building schools and churches and circulating periodicals.

The 1915 Armenian Genocide catalyzed a large-scale migration of Armenians from former Ottoman territories into Romania, where refugees were offered asylum. Over the course of the next several decades, newcomers settled in various locations, such as Bucharest, Constanta, and Pitesti. At the time of the first Romanian census, Armenians amounted to approximately 16,000 persons, whereas, according the Hungarian census, largely Catholic Armenians made up 7,687 persons of the total population (Horváth and Veress Reference Horváth, Veress, Siekierski and Troebst2016). In 1919, the Union of Armenians in Romania (UAR) was established to help facilitate Armenian refugee resettlement. The organization played a critical role in helping newcomers until Romania’s mid-century regime change.

Under the communist regime (1945–1989), Romanian Armenians’ capacity to organize and thrive decreased. Apart from their two ecclesial branches, Romanian Armenians had little means to perpetuate a cultural or linguistic identity. Consequently, during the mid- and late twentieth century, the scattered Armenian communities shrank to insignificance. Confronted with the challenges of navigating the increasingly tenuous political milieu of communist Romania, Armenians immigrated to several outposts – Hungary, Soviet Armenia, Western Europe, and North America. Even those who remained have had to contend with assimilation, intermarriage, and language attrition. As of 2011, census data indicate that only 1,361 Romanian Armenians remain in the country. To be sure, these shrinking numbers have been offset by some emigration from the Republic of Armenia. In addition, census data can provide misleadingly deflated statistical reports; however, even with these considerations factored, the dispersed Romanian Armenian communities have nearly disappeared.

In 1990, Romanian Armenians resuscitated the UAR and shifted its focus to cultural preservation. At the time of this writing, the UAR operates in 12 locations throughout Romania. Apart from the two church branches, the UAR is the sole organization operating in Romania. As the article’s findings attest, its leadership has played an important role in explaining the community’s ability to flourish despite rather stark demographic realities.

Methods

In late 2019, I spent ten weeks in Romania, where I undertook extensive participant observation and conducted over 30 in-depth interviews. In terms of the participant observation, I attended many cultural events on various issues related to Armenians and other ethnic communities. These events included concerts, religious and cultural festivals, political debates, book launches, and a commemoration of the Armenian Language, Alphabet, and Culture Day at the Romanian Academy.

For interviews, I met with a diverse range of officials and community members. Most of these interviews took place in Bucharest; however, I also traveled to and interviewed in other locations, such as Constanta, Brasov, and Cluj County. I met with various members of the Armenian community and many others – officials from the UAR and the Armenian Churches, the Armenian ambassador to Romania, Romanian academics and civil rights activists, and relevant officials from the Romanian government (both contemporary and those active in the 1990s). Interviews with officials from the Romanian government included a counselor of state, secretaries of state from the Department for Interethnic Relations (DIR) and the National Religious Groups, a judge from the Romanian Constitutional Court, an official from the Romanian Presidency, and several presidents and members of ethnic organizations, such as the UDMR, the Democratic Forum of Germans in Romania, the Party of the Roma, and the Federation of Jewish Communities of Romania. These interviews provided me with a diverse frame of reference on the various aspects of Romania’s system of PR.

The interviews were conducted largely in English. A few interviews took place in Romanian or Hungarian. For these interviews, a translator was provided. I audio recorded and transcribed interviews. For those conducted in Romanian or Hungarian, I crosschecked translations of quotes with two separate translators to ensure consistency and reliability. In choosing whom to interview, I used both selective and snowball sampling methods. Relying on my pre-existing Armenian network, I initially connected with several people from the Armenian Church of Romania – in particular, Bishop Datev Hagopian. The Primate of the Romanian Diocese of the Armenian Church, Bishop Hagopian is a visible and influential community member. He introduced me to various members of the Romanian Armenian community, which included elected officials and UAR leadership. Through these Romanian Armenian officials I met and interviewed various members of designated national minority organizations as well as the Romanian government.

In addition to interview data, I consulted archival data from Romania’s Constitutional Court in order to better understand the evolution of the state’s articles related to national minorities. For archival data in Romanian, I sought assistance from two separate translators to ensure the accuracy of translations. From the DIR, I also gained access to documents from the last five years pertaining to the state’s allocations to national minorities. And I relied on the official census data in determining the population sizes of the national minorities.

Institutional Activism in Post-Communist Romania

Institutional Activism

Institutional activists have access to resources and decision-making processes and work on issues related to various movements (Tilly Reference Tilly1978; Pierson Reference Pierson1994). By using their resources and access to influence political elites, these activists help redirect policy agendas and achieve the goals of social movements. The scholarship traditionally assumed social movements occur outside or on the margins of the state (McCarthy and Zald Reference McCarthy and Zald1977; Tarrow Reference Tarrow1998; Tilly Reference Tilly1978; Turner and Killian Reference Turner and Killian1972). This scholarship therefore typically claims groups “have little institutional power and are on the bottom of the racial, ethnic, and class hierarchies” (Valocchi Reference Valocchi2010). Based on this assumption, the scholarship often argues that the state’s political opportunity structures respond to social movements depending on insider elites’ sympathetic or antagonistic orientations to specific movements’ goals (Pettinicchio Reference Pettinicchio2012). But institutional activism scholarship challenges this insider/outsider dichotomy by expanding the traditional, “bottom-up” approach and re-situating activists inside of governments. This scholarship therefore complicates traditional accounts of cause and effect in evaluating the evolving organization and philosophy of states in reaction to social movements.

As the scholarship has pointed out, institutional activists often play an important role after protest cycles (Staggenborg Reference Staggenborg2001; Ruzza Reference Ruzza1997). As Carlo Ruzza claims, institutional activists pressure elites to accept popular opinions among other activists operating outside of governments. But the scholarship has also noted the entrepreneurial or opportunistic motivation behind a great deal of institutional activism – that is, the scholarship unpacks the extent to which institutional activists pursue policy issues based on their personal histories or experiences and career ambitions (Costain and Majstrovic Reference Costain and Majstrovic1994; Reichman and Canan Reference Reichman, Canan and Humphrey2003; Sulkin Reference Sulkin2005).

The institutional activism framework elucidates the dynamic exchange between actors inside and outside of government. The scholarship has applied this framework from multiple angles – insider activists mobilizing constituencies (Costain Reference Costain and Majstrovic1992; Scotch Reference Scotch2001); insider activists taking on movement causes (Santoro and McGuire Reference Santoro and McGuire1997); and outsider activists becoming insider activists (Banaszak Reference Banaszak, David, Jenness and Ingram2005, Reference Banaszak2010) – but it largely evaluates social movements in Western European, Australian, or North American contexts. Post-communist revolutions, however, also stand to benefit from the institutional activist framework.

Romania’s transitional government – CPUN – consisted of many activists, who helped create extensive legislation regarding ethnic minorities. Because many CPUN officials brought their activist backgrounds in the Romanian Revolution into the transitional government, their initiatives on minority rights exemplify “top-down” institutional activism. Given the distinct organization of Romania’s version of a PR system, case studies of the CPUN and the enactment of their minority legislation can broaden the existing institutional activism scholarship.

Institutional Activism in Post-Communist Romania

One of the institutional activists in post-communist Romania’s transitional government was Varujan Vosganian. As with many of his activist peers, he had little political experience before joining the CPUN government. While initially a political outsider, the revolution provided an opportunity to take his activism “inside” the transitional government and develop new platforms, particularly for ethnic minorities in Romania. Vosganian and his colleagues played an especially important role in drafting the constitutional provision, which would, ultimately, give rise to Romania’s affirmative electoral system.

Romania’s legal and archival records from the transitional government, Geneza Constituției României 1991: Lucrările Adunării Constituante (Genesis of the Constitution of Romania 1991: The Work of the Constituent Assembly) provide articles, debates, and theses of Romania’s draft Constitution. In terms of the draft provision for national minorities, the archive includes the initial proposal to the assembly, in which Vosganian argues that the inclusion of small minorities in parliament will facilitate Romania’s transition to democratic governance:

[N]ational minorities, and particularly those who have a relatively small number of members, cannot elect a representative under the electoral law. So I will argue for the advantage of representing them ex officio in parliament … Our position is that we have to make efficient the transition towards democracy, and that our points of views of the communities that we represent have helped the transition and have helped the Romanian nation on the way toward political transition. So the representation of all national minorities in the Parliament of Romania is something acquired that we can be proud of (Ioncică Reference Ioncică1998 456).Footnote 6

This provision seeks to protect the interests of smaller minority populations. It helped establish the constitutional provision on how the Romanian state would interact with designated national minorities.

Vosganian explained his role in this process to me, saying, “I discussed with every senator. I was member of the chamber. In the Senate, they didn’t understand. [So] I discussed with all the senators, all the senators. I made a list, and I met every senator to convince him about the necessity of the climate of the country to have the national minorities to have political power … .”Footnote 7 Taking advantage of his place inside of the provisional government and the political “climate of the country,” Vosganian operated as an institutional activist in helping draft a constitutional provision, which would benefit not only several ethnic communities, but also restructure post-communist Romanian institutions. The Romanian Revolution changed the composition of political elites inside of the government, and several of these elites, who were themselves activists, used the charged political atmosphere to push forward transformative legislation and pressure the remaining elites still in power (such as the first president of post-communist Romania, Ion Iliescu).

While several factors and actors set the stage for reform, Vosganian’s activism highlights the role of institutional activists in Romania’s transitional government. Also, because of the salience of the minority issues, particularly related to ethnic Hungarians, existing elites proved particularly receptive to legislative and institutional reform to advance their own initiatives. By distributing disproportionate influence among several small minority populations, Romanian leadership effectively neutralized the Hungarian minority.

But, as the scholarship reflects, institutional activists often operate as political entrepreneurs, as well. Based on their personal backgrounds, interests, and ideologies, institutional activists also advance their own careers or their own personal causes. This also proved true for Vosganian. While the provision relates to several national minorities, Vosganian and several members of the UAR stressed that Vosganian operated very much with his own career and the Armenian minority in mind. As an Armenian official shared:

The first motivation — or at least one of them — was to give life to the Armenian Union. The Armenian Union was suspended, in a way, during the communist period. And during the interwar period, the…government wasn’t giving a lot of money to the minorities. So the minorities had to help themselves. But after the 89, there weren’t that many Armenians left. And there weren’t any very wealthy Armenians, who could keep the community. So it was the only way…for the minorities to survive and keep their tradition after Communism…was by taking money from the government.Footnote 8

Thus, while the provision ostensibly reinforces the “minority regime” prevalent in post-communist Romania, Vosganian (as with others) took advantage of the circumstances to insert himself into Romania’s political system and promote the small, largely assimilated Armenian community. Vosganian was deputy from the UAR and parliamentary leader in the lower chamber from 1992 to 1996 (Protsyk Reference Protsyk2010a). From 1996 to 2000, he served in the Senate. After, he also served as the Minister of Economy and Finance (2006–2008) and as the Minister of the Economy (2012–2013).

In addition, Vosganian’s activism has ensured that the UAR receives a disproportionate amount of state support as compared to other recognized groups. Apart from the very small Albanian community (407 members), Romanian Armenians (and, more specifically, the UAR) receive among the largest allocations based upon population size (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. State allocations based on national minority population size.

As the figure reflects, of the groups with over a thousand members, the Armenian minority organization received a higher per capita allocation on average between 2015 and 2019.

Ethnic Intermediation in Post-Communist Romania

Ethnic Intermediation

As with institutional activism, the ethnic intermediation framework also explores how insider and outsider actors interact in making diverse claims to and reallocating resources from the state. But, while institutional activism typically analyzes when and how the goals of social movements influence political elites and redirect governmental agendas, ethnic intermediation focuses on the processes, which give rise to financial and symbolic reallocations. In diverse geopolitical contexts, ethnic intermediaries broker ties between their communities and several branches of government. By making demands of governmental elites, they seek to advance their groups’ interests through allocations from the state. Their interventions seek to compensate inequitable access to the state, which results from barriers related to socioeconomic class or racial segregation (Roniger Reference Roniger1994). In exchange for support from governmental elites, intermediaries offer elected officials their communities’ voter support (Chazan et al. Reference Chazan, Lewis, Mortimer, Rothchild and Stedman1999).

In the existing scholarship, ethnic intermediaries operate either as officials inside a ruling patron’s party – that is, “core intermediaries” – or as officials who advance their personal (and/or organizational) interests, but operate outside of the governing political institutions – that is, “peripheral intermediaries” (Scott Reference Scott1972). In diverse contexts, ethnic intermediaries help unpack the distinct opportunities and barriers states introduce to members of the polity. Analyses of the strategies upon which ethnic intermediaries rely, therefore, help unpack the philosophies and organizations of varied, multi-cultural states (Meyer Reference Meyer2004; Zappala Reference Zappala1998; Chazan et al. Reference Chazan, Lewis, Mortimer, Rothchild and Stedman1999; Awedoba Reference Awedoba, Odotei and Awedoba2006).

While the scholarship initially assumed ethnic intermediation occurs among electorally large, socioeconomically disenfranchised groups, more recent scholarship has introduced several case studies of ethnodiasporas, which complicate these assumptions (Fittante Reference Fittante2019; Reference Fittante2020). This scholarship demonstrates that small yet prosperous ethnic groups also gain disproportionate political influence through ethnic intermediation. In diverse geopolitical contexts, ethnodiasporas often compensate their small size by devising creative strategies to exercise disproportionate influence. In addition, they often rely on their social cachet – as well-integrated, “model minorities” – to intermediate between themselves and the diverse states in which they live. The ethnic intermediation model – particularly, the core intermediation model – complicates scholarly assumptions, which traditionally understood collective action as occurring outside of the state apparatus (McCarthy and Zald Reference McCarthy and Zald1977; Tarrow Reference Tarrow1998; Tilly Reference Tilly1978; Turner and Killian Reference Turner and Killian1972). However, more recent analyses of smaller groups, who act within the state, have not been applied in contexts with affirmative electoral arrangements for ethnic minorities.

Ethnic Intermediation in Post-Communist Romania

Romanian Armenian ethnic intermediaries reinforce the primary findings of the existing scholarship. For example, I met with UAR officials in Cluj and Gherla, where they described how the constitutional provisions have influenced their communities. In Gherla, the president of the local branch of the UAR, Ezstegar Ioannis, explained how the organization supports the community:

The UAR sends to our account – to the account of the UAR of Gherla – money. An amount. We may spend this money on cultural events. So: dance group, (inaudible), Saint Grigor [festival] … We have money. They have never refused us… [I]f we don’t have money, we just call [them] … Moreover, when I reclaimed the Armenian club, the UAR financed the renovation. Huge amount. Only the UAR … And thus our group does not decrease. Although there are deaths, but others are coming in, because they see that we are active… . And then they see, that moreover, it’s not only others are also coming in. For example, Protestant friends – from childhood – from Sweden come, and they don’t go to the Protestants, they don’t go to the Catholics, they come here to the church and then they come in here for a coffee, to talk …Footnote 9 , Footnote 10

Ioannis describes peripheral intermediation in contemporary Romania: while the heads of ethnic organizational branches do not operate inside of the government, they work with co-ethnic officials in order to assess community needs to allocate resources from the state in order to benefit their local communities – in this case, not only to the local Armenians, but non-Armenians, as well. Although extra-governmental groups often encounter challenges making claims to and accessing resources from the state, Romania’s PR or mixed system creates a direct line between local ethnic organizations and federal funding. In Gherla and elsewhere, this peripheral intermediation enables the community to promote and maintain its ties to its cultural heritage.

But case studies of ethnic intermediation in Romania also expand and complicate the existing scholarship. As stated, this scholarship typically distinguishes between those inside of the government and those outside of it. But Romania’s system demonstrates that intermediaries can also operate in both capacities simultaneously. Several MPs’ dual roles as deputies in parliament and leaders of ethnic organizations expedite legal and administrative processes. This dual-capacity removes several barriers, which ethnic organizations typically confront when lobbying for influence among state officials. Rather, this system gives members a direct line of communication and access to state funds.

For example, the Romanian government has designated October 12 a day of commemoration of the Armenian alphabet, language, and culture. The current deputy from the UAR and leader of the minorities parliamentary group, Varujan Pambuccian,Footnote 11 explained his role in the bill’s creation:

The idea came from an Armenian lady in Constanta, who asked a colleague of mine to tell me this…I asked Serpazan [bishop in the Armenian Apostolic Church], which is the most appropriate day for Mesrop Mashtots. And he told me it is best to celebrate on the day of the translators. The problem was that day is not a fixed date, and you cannot put in legislation a variable day. [W]e decided to have the date of this year, which is the 12th of October. So that’s why we popped it as this day. Then it was a very fast process during the last six months in the parliament to pass it quick…because we wished to have it celebrated it this year. So we passed very fast through the Senate and Chamber of Deputies. Then I talked to the presidency to promulgate the local as quick as president. So he did. And it was promulgated before the 12th of October. We were very happy.Footnote 12

This account captures a particular form of ethnic intermediation: a community member had an idea, which, indirectly, she communicated to Pambuccian, who, in turn, used his role as both a cultural and political leader to overcome internal challenges to expedite the passage of legislation. By working with MPs and the office of the presidency, Pambuccian brought about an important piece of symbolic legislation for Romanian Armenians. This form of intermediation highlights how intermediation works in contemporary Romania, but also complicates the existing binary between core and peripheral intermediaries: in intermediating on behalf of the UAR, Pambuccian acted both as a governmental official (core) as well as the leader of an ethnic organization (peripheral).

While the focus of this article’s findings pertains to the Romanian Armenian minority organization, fieldwork interviews with other small, yet prosperous ethnodiasporas reinforce the same insights. Members of the organization representing Romanian Jews, for example, described their initiatives in very similar language as that used by Pambuccian. For example, in describing his organization’s successful efforts to criminalize Holocaust-denial and create a state-funded museum dedicated to the Holocaust, the current deputy of the Jewish Federation of Romania, Silviu Vexler, also articulated his dual, core-peripheral role:

The topic of the bill was to set the judicial aspects related to the creation of the museum itself, and to give the building – which was the main problem – the space. So I spent summer searching for a place. I found a six-story historical building with 8,000 square meters of usable space across the street from government…And the bill gave the building to the Wiesel Institute, who is going to coordinate the museum. The President signed the bill. The bill was published in the official gazette. Institute took over the building as provided by the bill … The bill was signed – for the first time – in a public ceremony. It was the first time the President of Romania did this.Footnote 13

Acting as both a core and peripheral intermediary, Vexler created and helped pass legislation on behalf of the Jewish community. Unlike traditional accounts of core intermediaries – who risk seeming biased (Fittante Reference Fittante2020) – Romanian intermediaries are expected to maintain an ethnic-slanted bias. This removes several potential barriers in the bureaucratic processes of intermediation. Thus, Romania’s system of PR expands the intermediation scholarship by demonstrating the limitations of the existing core/peripheral binary model.

Discussion

The findings of this case study offer new analytical insights into institutional activism and ethnic intermediation scholarship. Romania’s PR system complicates the existing unidirectional and binary models of institutional activism and core/peripheral intermediation. CPUN institutional activists – and, later, ethnic intermediaries – restructured Romanian institutions and minority-oriented narratives. While the intermediation scholarship typically understands intermediaries’ roles as unidirectional – that is, an ethnic intermediary operating on behalf of his or her ethnic group’s interests – the Cathedral in Gherla demonstrates that these initiatives extend to several other community members, as well.

Also, while the institutional activist scholarship acknowledges that actors can operate in both insider and outsider capacities, the intermediation scholarship has not demonstrated this phenomenon as explicitly. However, as deputies from minority organizations reflect, intermediaries can operate in both core and peripheral capacities simultaneously. For those designated groups, this dual capacity makes intermediation between the state and ethnic organizations far more direct.

Furthermore, the scholarship often assumes that small ethnic populations must rely on coalitions in order to compensate their numbers (Posner Reference Posner2005; Koinova Reference Koinova2019; Fittante Reference Fittante2019), whereas large, socioeconomically disenfranchised groups benefit from their electoral influence. But intermediation in Romania challenges these assumptions. In Romania, smaller groups often have a clear advantage over larger ethnic minorities. While not undermining the existing scholarship, the findings of this article force scholars to reevaluate their assumptions about how small yet mobilized ethnic communities overcome demographic limitations in making sustained claims to and reallocating resources from the state.

Still, this article broaches several topics, which warrant more scholarly attention. For instance, it argues that many of Romania’s ethnic policies resulted from the opportunism of several actors, who sought either to promote their own agendas and/or neutralize the Hungarian minority. Romania’s interethnic tensions reflect the extent to which, for many post-communist countries, entry and integration into the EU involve confronting an imperial past. Several other member states, such as Bulgaria, Estonia, and Latvia have developed their own approaches to ethnic minorities in order to navigate entry into the EU and deal with their own imperial histories. How have these distinct approaches to ethnic minorities facilitated European integration? And what roles do ethnic activists and intermediaries play in these distinct contexts? Furthermore, this study has focused on small, privileged groups, such as Armenians and Jews, in Romania. Representatives from large socioeconomic groups – the Roma, in particular – presented a very different reality. In interviews, they spoke of insurmountable challenges the Roma confront daily in terms of housing, education, segregation, bullying, and many other social injustices. Future research should investigate the socioeconomic implications of distinct groups’ capacity to intermediate among themselves and states with PR and reserved seats systems.

Also, while institutional activists and ethnic organizations intermediate between themselves and the government, those who remain unaffiliated are largely neglected. Several members of the Romanian Armenian community, who are unaffiliated with the UAR, told me that they are not able to participate because the constitutional provision acts only on behalf of single organizations. As a result, the provision assists only those whom the state recognizes – that is, those affiliated with the organizations. Romania’s ethnic provision often alienates and excludes large segments of the minority communities it purports to benefit. Future scholarship should investigate how unaffiliated members of minority organizations engage with the Romanian state.

And future analytical scholarship could fruitfully apply constructivist ethnicity frameworks in unpacking affirmative electoral systems. Because the state offers funding based on needs and population sizes, this system creates an “ethnic industry,” in which organizations compete with other organizations to ethnicize Romanians of mixed ancestry. This phenomenon manifested itself several times during my fieldwork. In fact, several officials from the UAR spoke about their efforts to convince people in Transylvania of their Armenian roots. For example, Romanian Armenian filmmaker, Armine Vosganian, has produced a documentary about Hungarian Armenians, who identify as Armenian and yet remain affiliated with Hungarian organizations in order to receive benefits from the state. She also shared with me how she is working to revive Transylvanian Armenians of mixed ethnic ancestry, many who receive benefits from the Hungarian state or Hungarian organizations in Romania. On account of mixed heritage, policies of minority representation create competition in the so-called “revival” or reconstruction of ethnic identities. While my research did not dwell on the subject, I believe it is a rich topic for future scholarship.

Disclosure

The author has nothing to disclose.