Introduction

What does sceptical theism (ST) imply about the fine-tuning argument (FTA)? Does one undermine the other? If so, we must either give up an otherwise promising argument for theism or find non-sceptical theistic means for undermining the problem of evil. The problem is that arguments for ST seemingly imply that we can say nothing about what God would do in any circumstance, whether that be in permitting evil or fine-tuning a universe. The FTA, however, requires us to say that God would likely do the latter. Hence, the incompatibility.

This issue is a case study in the wider project of integrating ST with natural theology. If unresolvable, it threatens to unseat several theistic arguments (at least insofar as one is a sceptical theist): those from consciousness (Page Reference Page2020), the applicability of mathematics (Craig Reference Craig, Ruloff and Horban2021), and even the resurrection of Jesus (McGrew and McGrew Reference McGrew, McGrew, Craig and Moreland2009). All rely on our ability to ascribe a non-negligible probability to the claim that God would do a certain thing: create conscious agents, design a mathematically elegant world, and raise Jesus from the dead. ST’s (in)compatibility with the FTA therefore ought to interest a wide range of philosophers.

Although philosophers often assert that ST undermines natural theology, they hardly ever argue for that contention in detail. I contend that ST of any guise undermines the FTA, with one exception: Durston’s (Reference Durston2000) argument from the consequential complexity of history. I acknowledge, however, that the exceptional status I attach to Durston’s case fails if we cannot disregard data with an inscrutable likelihood when calculating theism’s posterior probability. This conclusion is a mouthful, but a succinct statement of my point is simple: the viable dialectical options for advancing both ST and the FTA are narrow indeed.

In section 2, I define ST and the FTA. In section 3, I argue that the most prominent forms of ST conflict with the FTA. In section 4, I then consider two tactics for ameliorating that conflict: reformulating ST and refashioning the FTA. I argue that both tactics fail. In section 5, I return to more conventional sceptical theistic manoeuvres and argue that Durston’s argument from the consequential complexity of history does not undercut the FTA but in fact supports it. I defend that claim from three objections: a revised attempt to assert incompatibility, the narrow scope of my solution, and Climenhaga’s (forthcoming) contention that ST undermines all warrant for theistic belief, the FTA included.

Defining terms

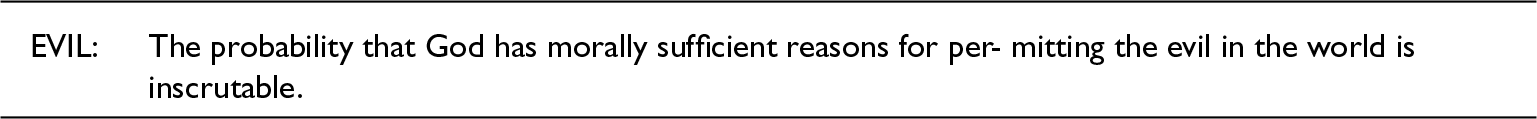

I follow Draper (Reference Draper and Kvanvig2016) in defining ST as the view that the evidential problem of evil fails because we cannot rationally assess the likelihood of the evil we observe given theism. Unlike a theodicy, a sceptical response aims to show not that the likelihood of evil conditional on theism is high, but that there is no way to assess that likelihood. It could be low, as the atheist claims, but it could also be high; we cannot say. Proponents often argue for ST by way of a subsidiary claim:

The assumption is that if we cannot say how likely it is that God has morally sufficient reasons for permitting evil, then we cannot say that evil makes God’s existence unlikely.

The FTA, on the other hand, is the two-part claim that certain features of the laws of physics are fine-tuned for complex life, and that this fact is evidence for theism. Collins (Reference Collins, Craig and Moreland2009) points to (i) the physical constants embedded in the laws of nature, numbers dictating the strengths of fundamental forces or the masses of fundamental particles, (ii) the initial conditions of the universe like the ratio of matter to antimatter or the universe’s initial low entropy, and (iii) the mathematical form of the laws of nature. These features are ‘fine-tuned’ insofar as a slight change to their actual values would render the universe inhospitable to complex life. Barnes (Reference Barnes2019) then provides a standard way one might connect these scientific discoveries to theism:

1. For any two theories T1 and T2, in the context of background information B, if it is true of evidence E that P(E|T1&B) ≫ P(E|T2&B), then E strongly supports T1 over T2.

2. The likelihood that a life-permitting universe exists on naturalism is vanishingly small.

3. The likelihood that a life-permitting universe exists on theism is not vanishingly small.

4. Thus, the existence of a life-permitting universe strongly supports theism over naturalism.

Premise (3) is our focus. Rephrased, it says:

The idea is that to show that fine-tuning is evidence for theism against naturalism, we must show that theism makes fine-tuning more probable than naturalism. Notice that this premise concerns a claim about divine psychology, what God would likely do in some circumstance.

Exploring incompatibility

The incompatibility thesis, then, is this: the arguments sceptical theists give for EVIL undermine the arguments fine-tuning advocates give for LIFE. In evaluating this thesis, I will, first, provide a general overview and second, examine the details.

The big picture

While some philosophers once argued that a morally perfect being would eradicate all evil whenever it had the power to do so, most now recognize that such a being ‘would [only] prevent any evil that [it] had no morally sufficient reason to permit’, where such a reason is an ‘explanation of why [it] allows that evil that renders blaming [the being] … inappropriate’ (Draper Reference Draper1992, p. 303). Given the possibility that an evil we observe is necessary for realizing some greater good, or avoiding a greater evil, we cannot claim that God ‘probably’ does not have morally sufficient reasons for allowing the evil in question. EVIL then encapsulates this intuition. But if so, then the evidential problem of evil fails.

Many philosophers contend that this reasoning is detrimental for natural theology (Benton et al. Reference Benton, Hawthorne, Isaacs and Kvanwig2016; Bergmann Reference Bergmann, Flint and Rea2009; Draper Reference Draper and Howard-Snyder1996; Gale Reference Gale and Howard-Snyder1996; Manson Reference Manson, Oppy and Koterski2019; Wilks Reference Wilks2004). Draper (Reference Draper and Howard-Snyder1996) writes that ‘many [theistic arguments] rely on claims that God would be likely to create a world which contains order or beauty or conscious beings’, adding that advocates of ST, ‘if they are to be consistent, must treat such claims with skepticism’ (p. 188). Similarly, Gale (Reference Gale and Howard-Snyder1996) contends that if we grant ST, then ‘we never could be justified in asserting [God’s existence] … on the basis of worldly goods, such as natural beauty, purpose, order, etc., thereby destroying natural theology’ (p. 217). Manson (Reference Manson, Oppy and Koterski2019) is one of the few to connect this claim with the FTA specifically, writing that ‘[s]keptical theists … ought to take the same attitude toward creation that they take toward evil: God and his ways are mysterious. If that is one’s view, the fine-tuning argument will have little force’ (p. 364).

The bone of contention, then, concerns those appeals to God grounded in moral considerations. Arguments for LIFE, unfortunately, explicitly appeal to the moral value of conscious agents, leaving them vulnerable to ST-reasoning. According to Collins (Reference Collins, Craig and Moreland2009), for instance, it is not improbable that God would create a universe where conscious beings could exist because God is perfectly good, and embodied conscious agents contribute ‘to the overall moral and aesthetic value of reality’ (p. 254). The basic logic is: God is good; creating conscious life is a good option; so, it is not terribly unlikely that God would take that option. However, if we can say that God would likely create conscious agents because they are good, then we can likewise say that God would likely not allow the Holocaust because it is bad. Conversely, if we cannot say the latter, then we cannot say the former. That is the perceived inconsistency.

If we understand ‘divine psychology’ to refer to facts about what God would choose to do in some circumstance, the incompatibility thesis rests on the following argument:

1. If standard ST arguments for EVIL succeed, then affirming any claim about divine psychology grounded in moral considerations is unjustified.

2. The standard argument for LIFE involves claims about divine psychology grounded in moral considerations.

3. Therefore, if standard ST arguments for EVIL succeed, then the standard argument for LIFE involves unjustified claims.

4. If the standard argument for LIFE involves unjustified claims, then LIFE is unjustified.

5. Therefore, if standard ST arguments for EVIL succeed, then LIFE is unjustified.

With (5) in place, one may either affirm ST and consequently deny LIFE, or instead affirm LIFE and conclude that arguments for EVIL are unsound. Either way, we cannot have our cake and eat it too.

In assessing the case for incompatibility between LIFE and EVIL, I will articulate the standard argument for the former, and then evaluate it against multiple considerations advanced in defence of the latter. As with most things, the devil is in the details.

The case for LIFE

Fine-tuning advocates often appeal to the objective value of conscious agents to ground LIFE (Barnes Reference Barnes2018; Collins Reference Collins, Craig and Moreland2009; Rota Reference Rota2016; Swinburne Reference Swinburne and Manson2003). The chain of logic is something like:

1. If God is perfectly good, then the epistemic probability that He would create a universe fine-tuned for intelligent life is not terribly low.

2. God is perfectly good.

3. Therefore, the epistemic probability that God would create a universe fine-tuned for intelligent life is not terribly low.

Premise (2) follows from the definition of ‘God’ operative in (some) versions of the FTA. Premise (1) follows because creating self-conscious beings would be a good thing to do. They have intrinsic moral value and make the world a better place than it would have been without them. Although writing in the context of an argument from consciousness rather than fine-tuning, Page (Reference Page2020) writes that ‘many moral goods appear to require conscious awareness, with these being goods of a different type, and seem more valuable than other types of goods applicable to non-conscious beings like trees’ (p. 342). Conscious agents, for instance, can develop significant moral characters and worthwhile relationships with themselves and with God.

More rigorously stated, I propose the following reconstruction of the sub-argument for (1):

1.1. If (a) embodied moral agents are objectively valuable, then (b) if God is perfectly good, then the epistemic probability that God would create such agents is non-negligible.

1.2. If the epistemic probability that God would create embodied conscious agents is non-negligible, then the epistemic probability that God would design a

1.3. fine-tuned universe is non-negligible.

1.4. (a).

1.5. Therefore, (b).

1.6. Therefore, if God is perfectly good, the epistemic probability that God would design a life-permitting universe is non-negligible.

Premise (1.1) captures the intuition that, not only is conscious life good, but it is one of the best goods there is. A perfectly good being would therefore not be unlikely to create it. Premise (1.2) then connects that point to a claim about a fine-tuned universe: given that it is not improbable that God would choose to create conscious life, it is also not improbable that He would elect to do so within the arena of a physical universe, rather than preferring free-floating unembodied minds. Both premises, then, are claims about divine psychology, and it is these that are most likely to fall prey to sceptical theistic arguments.

The case for EVIL

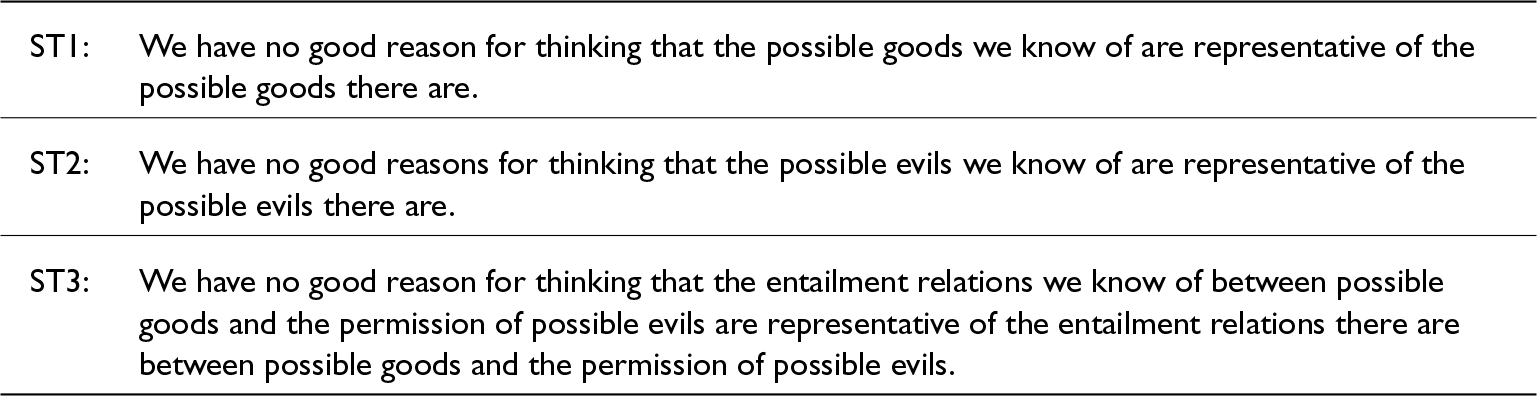

While several philosophers are keen to claim that sceptical theistic frameworks undercut all of natural theology, there are few attempts to flesh-out that contention in detail. I will do so here. In developing his brand of ST, Bergmann (Reference Bergmann, Flint and Rea2009, Reference Bergmann, Clark and Rea2012) delineates three claims that ostensibly undermine the problem of evil:

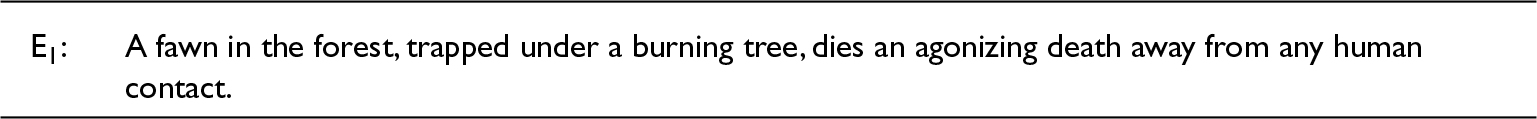

To illustrate the effect these points have on the problem of evil, consider an instance of horrible suffering first outlined by Rowe (Reference Rowe1979):

When contemplating E1, most will conclude that there is no possible morally sufficient reason for allowing it. But if we grant the above three claims, this conclusion is no longer warranted. Given (ST1) and (ST2), even if all known goods and evils possess the property of ‘failing to feature into a morally sufficient reason for E1’, we have no reason to think that all possible goods and evils share that property. Perhaps our sample of goods and evils is not representative of all goods and evils that there are, much as the chihuahua is not representative of all dogs with respect to the properties of height and weight. Given (ST3), the situation is even worse: we may grant that none of the entailment connections that we know of between known goods and evils feature into a morally sufficient reason for E1, but there may be unknown entailment connections between even known goods and evils that would do the trick. Thus, (ST1) and (ST2) remove our warrant for concluding that unknown goods and evils do not justify God in permitting E1, and (ST3) removes any reason for concluding that known goods and evils do not so justify God. Thus, our intuitive argument from apparently pointless evil fails.

Unfortunately, however, we can parody this reasoning to undercut the warrant for LIFE. We have no reason to think we grasp the range of goods such that what we perceive is representative of the goods that might present themselves to God explanatorily prior to designing the universe. Consider premise (1.1). We contemplate the reasons God might have for creating conscious agents. For any possible good x that involves no reference to such agents, we cannot come up with one that outweighs the intrinsic good of the latter. We therefore infer that there are no such goods; or at least, there are not so many that the probability of God’s creating conscious agents would be negligible. But corresponding versions of (ST1) and (ST2) seem to undercut our inference here: we lack justification for thinking that the x’s of which we are aware are representative of all possible x’s with respect to the property, outweighing the moral good of conscious life.

In short, if Bergmann’s sceptical framework is the only way of arguing for EVIL, then premise (1) in the incompatibility argument is true. But there are other formulations of ST that do not reduce to the above three theses. Do these do any better?

It seems not. Wykstra’s (Reference Wykstra1984) seminal paper lands us in complete scepticism about divine psychology. His defence centres around the thesis of disproportionality, the claim that what God sees and grasps is vastly different from what we in our finitude comprehend. Wykstra then utilizes this claim (in conjunction with the so-called CORNEA principle, details of which need not deter us) to undermine the inductive inference involved in claiming that God could not have a morally sufficient reason for permitting evil: given that there is no known reason for some evil, there probably is no unknown such reason, either. He compares our judgement to a one-month-old attempting to understand the motives of their parents. We, like the child, have no justification for our inductive inference from the known to the unknown. But if such a thesis concerning the cognitive gap between God and us is weighty enough to remove our warrant for passing judgement on what God may or may not do with respect to evil, then it is so strong that it also undercuts our ability to speculate about what God would do in any circumstance whatsoever, designing a universe included. Such a thesis has no limiting principle.

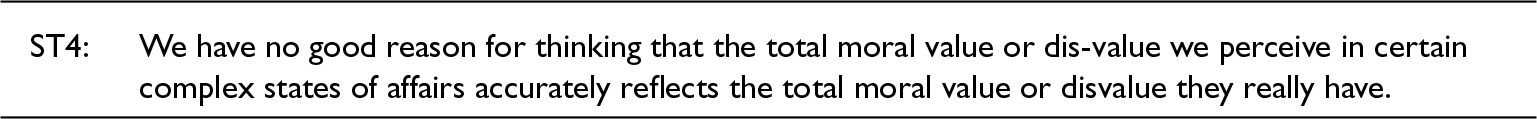

Similarly, Hendricks (Reference Hendricks2023) version of ST is equivalent to a fourth thesis that Bergmann articulates:

(ST4) reflects scepticism about our ability to weigh complex circumstances against one another to determine which one is more valuable. As van Inwagen (Reference van Inwagen1991) argues, our intuitions may not be reliable enough to warrant concluding that there is no state of affairs that might justify the goods and evils in the actual world. But like Wykstra, (ST4) has no limiting principle, and that undermines the FTA; while a universe containing three lonesome argon atoms may not seem to outweigh the value of a universe with conscious agents, we can have no confidence in our intuitions here. We therefore lose any reason to affirm (1.1) or (1.2) in the argument for LIFE. Indeed, Hendricks himself is candid about its implications for natural theology, writing that such an ST ‘prevents us from inferring from our knowledge of the perceived value of conscious agents to their actual value’ (p. 215).

Alston (Reference Alston1991) combines many of these considerations under one framework – but if these points individually land us in scepticism about divine psychology, combining them will change nothing. Poston (Reference Poston, McBrayer and Dougherty2014), however, contends that several considerations Alston pinpoints are ‘compatible with thinking that a perfect being will bring about certain kinds of states of affairs and prevent others’ (p. 317). I disagree, at least in the present context. Consider just two cognitive limitations Poston isolates: the complexity problem and the playbook problem. The former is the claim that ‘human beings face significant cognitive limitations in reliably assessing intricate situations’ (p. 311), a point Poston takes to undercut our judgement that various theodicies are inadequate justifications for God’s permitting evil. Evaluating theodicies is complicated, involving several philosophical problems at once. But, aside from the fact that this point would lead to agnosticism about every philosophical issue, evaluating the FTA itself is enormously complex, involving physics, probability theory, Bayesian epistemology, integration with the problem of evil, and so on. If we cannot assess a specific theodicy, we cannot assess the FTA. The latter issue is that ‘we lack knowledge of which options are metaphysically possible given certain goals’ (p. 213), a modal scepticism Poston claims renders us incapable of evaluating the free-will theodicy (i.e. God permits the evil in the world because doing so is a precondition for bringing about a world with free creatures). If this vague observation about our modal limitations prevents us from saying that there is a metaphysically possible world with free creatures but less pain and suffering, then this same concern will also remove our reasons for thinking that it is metaphysically possible that there is a world of free creatures that is net-positive.Footnote 1

The takeaway point is simple: it is very difficult to conjure up a body of considerations that is (i) of sufficient strength to undercut our judgements of God’s possible reasons vis a vis permitting evil, but (ii) not so strong as to undercut the inferences involved in the FTA. It is a tightrope walk that no one has successfully carried out. I conclude that ST of the above varieties does not bode well for the FTA.

Refashioning sceptical theism and LIFE

I will now examine three other ways one might try to diffuse the argument for incompatibility, arguing that each fails.

Questioning the argument’s significance

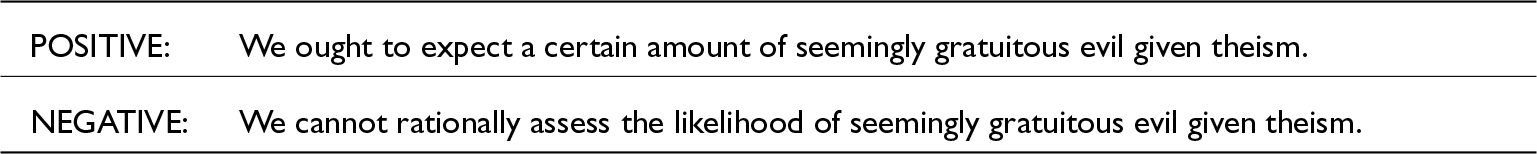

DePoe (Reference DePoe, McBrayer and Dougherty2014) presents a novel version of ST and, although he does not consider its relationship to the FTA, it would be profitable to see if his proposed framework avoids undermining it. That framework does not undercut any premise in the argument for incompatibility but would instead challenge the argument’s significance. DePoe abandons defence of EVIL, instead replying to the problem of evil in a different way. He begins by distinguishing positive from negative ST:

Traditional versions of ST affirm NEGATIVE (a thesis I take to be equivalent to EVIL),Footnote 2 but the idea behind POSITIVE is that we can see at least a few good reasons that a good God may create a world that appears to involve gratuitous suffering, even if such suffering does in fact serve a greater good beyond our ken.

Recall E1 mentioned above. This evil appears gratuitous – no possible reason we can come up with seems sufficient to justify allowing it. POSITIVE does not attempt to supply those reasons; rather, it makes the meta-level claim that God makes E1 appear gratuitous – preventing us from discerning its moral justification – to help ensure proper epistemic distance from God so that we can come to a freely chosen relationship with Him, and to allow us to display levels of self-sacrifice and compassion that would otherwise be impossible if we knew every evil served a greater good. The crucial point is that by suggesting positive reasons for expecting a diminished ability to assess the purposes of certain evils given theism, rather than negative reasons for doubting our cognitive capacities in general, one ostensibly avoids general-level scepticism about God’s psychology.

My reservation about positive ST is that if NEGATIVE is true, then POSITIVE is false. Rationally affirming the latter requires that arguments for the former fail. For consider: if Bergmann is right, for instance, then we do not know if the goods we know of are representative of all the goods there are with respect to the property, featuring into a morally sufficient reason for allowing the appearance of gratuitous evil. Of course, if there is no good argument for NEGATIVE, then the incompatibility here is insignificant. But if one does find the arguments for negative ST successful - and for my part, I find the argument from complexity outlined below viable - then one cannot avail oneself of positive ST.

Questioning premise (4)

Hendricks (Reference Hendricks2023) takes a different tack: proposing an argument for LIFE that does not rely upon moral considerations. Thus, even if ‘standard’ arguments for LIFE fail, it does not follow that LIFE is unjustified. He contends that if we assume a theistic metaethical framework according to which God is goodness itself and things are good insofar as they resemble God, we can construct an argument for LIFE that avoids ST’s sceptical implications. God is a conscious agent. It follows that anything that is a conscious agent is more like God than any non-conscious thing. But given the underlying metaethical theory, the more something resembles God, the better it is. The best possible worlds, moreover, will be those that resemble God to the highest degree, a status they can only have if they include conscious agents. Hendricks is clear that this argument is not an inference from the perceived value of agents to their actual value but is instead ‘rooted in conceptual analysis: we can see from the concept of God (that he’s a conscious agent) and theistic metaethics (God is the Good) that the best possible worlds contain conscious agents, and therefore that [the probability of conscious agents given theism] is high’ (p. 229).

It is not clear to me that this reasoning is compatible with (ST4), the version of ST Hendricks defends, but let that pass. The argument fails for a more fundamental reason: it does not undermine the problem of evil but merely shifts the conversation to a different conceptual level. If we can say that God would likely create conscious life because it is good (and it is good because it resembles God), then by the same token, we can say that God would prevent the Holocaust because it is bad (and it is bad because it does not resemble God – indeed, given that it involves the rampant destruction of conscious life, it is unlike God in a uniquely terrible way). Hendricks seems aware of this counterpoint when he admits that ‘we can refashion … arguments for atheism that make this conceptual move about resemblance’ (p. 233). His objection to this manoeuvre is that we can similarly refashion responses to those manoeuvres. One might argue, for instance, that ‘God creating creatures that resemble him with respect to freedom entails that they may perform acts that are in opposition to him’ (p. 234).

This counter-response does not work. First, we do not in fact resemble God in His freedom. God, being morally perfect, is not free to do evil. We are. We have ‘morally significant’ freedom while God has what Swinburne (Reference Swinburne2004) characterizes as ‘perfect’ freedom, freedom in the absence of any irrational influences that might tempt one to evil. Regardless of the labels, our ability to choose between good and evil is ‘a kind of freedom of choice that [God] does not possess himself’ (Swinburne Reference Swinburne2004, p. 120). Indeed, if God is essentially good, then, as Morriston (Reference Morriston2000) rightly asks, ‘would we not be more like God, and therefore better than we are, if he had made us “perfectly” free too?’ (p. 345). Appeal to freedom, then, will not work to subvert revised problems of evil. Second, such a response looks more like a theodicy than anything resembling an ST worth the name. Hendrick’s strategy of arguing for LIFE opens the door to similarly tweaked versions of the argument from evil, and if our only response to those problems is to advance a theodicy, then this revised argument for LIFE is antithetical to the whole point of ST. So, for the purposes of our discussion, Hendrick’s strategy is no longer pertinent.

Questioning premise (1)

Cullison (Reference Cullison, McBrayer and Dougherty2014) argues that one can withhold judgement on whether a normative superior has reason to permit some instance of suffering, while at the same time remaining confident about how such a superior may or may not act in other contexts. A normative superior is one who is both morally and epistemically superior to oneself. He offers the example of a professor of mathematics and a novice working out the solution to some equation. Suppose the novice comes up with ‘x = 5’, but the professor arrives at ‘x = 7’. The student ought to, at minimum, suspend judgement about his answer. But now suppose the student starts working on a second problem, and the professor has yet to write his answer. The student should, despite his earlier suspension of belief, believe that the teacher will arrive at the same answer as they. Cullison writes that ‘[w]hen dealing with known epistemic superiors, there is a big difference between an actual case of disagreement and making predictions about future agreement’ (p. 258). Turn, then, to the case of observing some horrific evil. One cannot conclude that a normative superior such as God lacks morally sufficient reasons for allowing it to occur; this situation is analogous to the mathematician and the novice disagreeing about the answer to a complex math problem. However, that claim leaves untouched the inference about what God would do in other contexts where we do not know of a disagreement between the human and divine evaluation of the best outcome. Specifically, we can still claim that a fine-tuned universe, equipped for conscious life, is non-negligibly probable if God exists; this situation is analogous to the math student solving a problem before the professor.

As promising as this approach looks, the epistemological principle lying behind Cullison’s case allows the evidential problem of evil to go through unabated. Cullison (Reference Cullison, McBrayer and Dougherty2014, p. 251) reconstructs the evidential problem as follows:

1. There exist horrendous evils that God would have no justifying reason to permit.

2. God would not permit horrendous evil unless God had a justifying reason to permit it.

3. There is no God.

Against premise (1), Cullison argues that a plausible epistemological principle removes any warrant for affirming it: evidence that P is not evidence that no one else has weightier evidence that ![]() $\sim$P. So, even though I have evidence for concluding that some evil e is gratuitous, it does not follow that a normative superior does not have weightier evidence that e is in fact not gratuitous. This principle lies behind the inference in Cullison’s proffered analogy of the student and professor reaching differing solutions to the math problem: the student’s evidence that his answer is correct is not itself evidence that the professor does not have weightier evidence that a different answer is current.

$\sim$P. So, even though I have evidence for concluding that some evil e is gratuitous, it does not follow that a normative superior does not have weightier evidence that e is in fact not gratuitous. This principle lies behind the inference in Cullison’s proffered analogy of the student and professor reaching differing solutions to the math problem: the student’s evidence that his answer is correct is not itself evidence that the professor does not have weightier evidence that a different answer is current.

Consider, however, a different statement of the argument, one that I lift directly from Rowe (Reference Rowe2006, p. 80):

1'. Probably, there are pointless evils.

2'. If God exists, there are no pointless evils.

3'. Therefore, God probably does not exist.

Cullison’s epistemological principle does not undercut either premise. (1ʹ) is rooted in the evidence we do in fact have: we can discern no greater good, or avoidance of greater evil, that e might serve. As Cullison himself writes with respect to some proposition P, ‘the mere fact that I lack evidence concerning possible weightier evidence that someone else might have for the denial of P does not entail that I have a defeater for P’ (p. 260). Now just replace P with (1ʹ). Consider the example of perceiving a red stop sign that Cullison often refers to: if I see a stop sign, I cannot infer on that basis alone that someone else does not have better evidence that there is no stop sign; still, I should follow what evidence I do have and conclude that there is a stop sign. But now amend this example: I look out my windshield and do not see a stop sign. Even though I cannot conclude that no one else has better evidence that there is a stop sign, I should still conclude that there is no stop sign. The parallel with pointless evil should be clear (e.g. I look out at the conceptual terrain and do not see a reason for e). (2ʹ) is unaffected as well. So, based on my evidence, not conjectures about evidence available to God, I should conclude that (1ʹ) and (2ʹ) are both true and therefore (3ʹ) follows. With some rephrasing, the evidential problem of evil evades concerns about normative superiors.Footnote 3

Now, it is open for Cullison to reply that our evidence does not justify (1ʹ) – but then, we will want to know why. If Cullison appeals to any of the considerations that traditional sceptical theists advance, then we are right back to the problem of squaring ST with the FTA.

The complexity of history

Though I do not find Cullison’s new argument for EVIL persuasive, I agree that the right tactic is to reject premise (1) in the argument for incompatibility. Instead of offering a new defence of ST, however, I would like to draw attention to an older one: Durston (Reference Durston2000) and his argument from the consequential complexity of history.Footnote 4 I contend that it breaks the symmetry between LIFE and EVIL and allow one to affirm both.

History as an interwoven tapestry

Durston (Reference Durston2000, Reference Durston2005, Reference Durston2006) maintains that in determining whether some instance of evil x is gratuitous, we must know two things about x:

1. The consequences of x.

2. The consequences of changing the course of history so that x does not happen.

The reason that both conditions are necessary is that even if x results in an overall negative series of consequences, it may still be the case that had x not transpired, the world would have been even worse. To find out if x is gratuitous or not, we must therefore consider two things: (1) that segment of history that includes x and its consequences to the end of history (call this series ‘A’), and (2) a counterfactual segment of history that would have obtained had x not obtained (call it series ‘B’). We will designate the event that appears in x’s place y, where y is the best alternative to x, whatever that alternative may be. The following equations then give the total value of A and B (where a1... and b1... designate the consequences of x and y, respectively):

We then want to know if A and B are positive or negative, a sum we find by adding the value of x and y with all their attendant consequences. Durston then suggests that we can define an evil as gratuitous if A – B is negative (for this would mean that reality would have been better if x did not obtain), whereas if A – B is positive, then x is not gratuitous, for if it had not obtained, the world would have been worse.

But then consider: is the value of A and B for some actual instance of evil positive or negative? Durston argues that, considering the interconnection between historical events, we have no way of evaluating either series. He points out, for instance, that ‘[o]n the night Sir Winston Churchill was conceived, had Lady Randolph Churchill fallen asleep in a slightly different position … Sir Winston Churchill as we know him would not have existed, with the likely result that the evolution of World War II would have been substantially different’ (Reference Durston2000, p. 66). It would have been impossible for a person on the night of Churchill’s conception to discern (i) the connection between his mother’s sleeping orientation and the course of World War II, (ii) how world history would have changed had she lain in a different way, and therefore (iii) either A or B above (where ‘Churchill’s mother laying in the position she in fact did’ substitutes in for x). That point generalizes: we do not know the ultimate consequences for any past or present event, and we do not know what would have happened were God to have removed some event from the timeline. For that reason, we cannot evaluate the gratuity, or lack thereof, of any historical event.

One might counter that an omnipotent God can arrange causal lines of influence in whatever ways He pleases. Any which way Churchill’s mother chose could still have resulted in events unfolding just as they did – if God deemed it fit. Durston, however, contends that if the world contains libertarian free agents, then even considerations of divine omnipotence do not undercut the sceptical inference. Consider the following counterfactuals:

1. If Bob were offered a million pounds, he would immediately buy a lifetime supply of potato crisps.

2. If I were elected president in 2047, I would increase taxes.

3. If Mary’s boss promoted her, she would call her husband to celebrate.

If there are facts like these, facts about how free agents would act in any hypothetical circumstance, then it is impossible to know how the world would unfold were we to change some event. While we might have a pretty good guess about certain counterfactuals of freedom (e.g. I am confident that if I were offered a million pounds, I would not squander it on potato crisps), we could not know them with certainty and we could not know them all. Those uncertainties multiply the more choices free agents one considers. For that reason, we cannot say that any event in our history is gratuitous because we have no idea how free agents would choose to act in circumstances where that event did not obtain. Durston (Reference Durston2000) explains that while ‘we can certainly postulate with confidence that God could actualize a world in which [a] given evil did not occur … we would not know what the consequences would be that include the relevant decisions of free agents’ (p. 69) – that is, we could not calculate for series B. Only God, who presumably does possess knowledge of all hypothetical free choices, can make that judgment call and evaluate all possible timelines in light of the counterfactuals of freedom that obtain. Even given his omnipotence, God cannot force people to act freely in a particular way.

These counterfactuals of freedom therefore restrict the ways that even an all-powerful God can order the world, a point I will expand on below.Footnote 5

Why LIFE remains unaffected

Durston’s argument is a viable response to the problem of evil, one that is not obviously unsound and deserves reflection. But the crucial question for our purposes is whether the argument from complexity issues in scepticism about other aspects of divine psychology, principally whether God would design a fine-tuned universe.

Although speaking about Bergmann, Wilks (Reference Wilks, McBrayer and Howard-Snyder2013) writes that ‘the consequences of a seeming good may run quite contrary to its appearance too’, such that sceptical considerations with respect to evil and its consequences will apply ‘with equal force to any form of the design argument which appeals to the presence of goods’ (p. 460). Consider the act of God’s creating embodied life along with the attendant fine-tuned universe that houses it – call this series of events ‘L’. We can then reconstruct A and B as follows:

In light of the consequential complexity of history, can we say that A is a net positive? Recall premise (1.1):

1.1. If (a) embodied moral agents are objectively valuable, then (b) if God is perfectly good, then the epistemic probability that God would create such agents is non-negligible.

It seems that the inference from (a) to (b) is no longer justified. Given that we do not know the relevant counterfactuals, we cannot say that a life-permitting possible world is overall good. For all we know, the counterfactuals of freedom are such that the total moral good from the beginning of human history to the end is negative, in which case God would presumably not actualize that world. Conscious life, while intrinsically good, can introduce evils into the world. But if that is the case, we cannot know that (1.1) is true.

However, there is a subtle asymmetry here stemming from the distinction between ‘possible’ and ‘feasible’ worlds. Assume with Durston that there are such things as counterfactuals of freedom. In that case, then not every logically possible world is feasible for God to create. Suppose that, prior to creating the world, the following counterfactual is true:

a. If John were sitting before his desk on May 15, 2023, he would freely write an email to his boss.

If (a) is true, then it is impossible for God to actualize that possible world where John sits at his desk on May 15 and does not freely send an email to his superior – the relevant counterfactual restricts the scope of possible worlds that God can actualize. What goes for that specific counterfactual goes for all of them: they together delimit the range of possible worlds to a subset of feasible worlds that God can actualize.

Now, return to EVIL and LIFE. The defender of the FTA need only defend two modest claims: (1) there is at least one feasible world α where conscious life is not so deleterious and wicked that it would be a net-negative for God to bring it about, and (2) for all we know, the actual world is α.

The first point encapsulates the idea that one arrives at premise (1.1) in the argument for LIFE, not by an inductive survey of the value of our universe, but by reflecting on the value of conscious life in general. From that general point, it will follow that God is non-negligibly likely to actualize α, whichever world it might be. To undermine that claim, the sceptic would have to defend the epistemic possibility that the counterfactuals of freedom are such that in all worlds feasible for God to create, none of them are on balance more good than bad. This is a radical claim; it seems undeniable that in at least one feasible world, moral agents within are not so horrific that the world is more bad than good. After all, God has at His disposal the entire range of all possible persons from which He can hand-select a collection that guarantees that the world that results from their choices is an all-things-considered good.

The second point is that the defender of the FTA need only defend the epistemic possibility that the actual world is α. They do not need to demonstrate that it actually is. Far from undermining this point, Durston’s argument supports it. Given the bewildering interdependent nature of historical events, we cannot evaluate the total moral value of our history as it unfolds in the actual world. This epistemic situation seems to entail the key claim required for the FTA to go through: for all we know, the actual world is a feasible world α for God to create where free creatures do not generate a sum of evil that outweighs their own intrinsic good. Given the arguments set out in section 3.2, we can say that God is not terribly unlikely to actualize α. The burden of proof, then, is on the sceptic’s shoulders to demonstrate that the actual world is not α. By contrast, the proponent of the argument from evil cannot rest their case with the mere epistemic possibility that the evil in the world is gratuitous – they must show that it actually is, and therein lies the asymmetry.

Objections and replies

Consider three problems one might raise for my analysis.

1. Symmetry reasserted

Objection – If we can say that there is at least one feasible world α of conscious agents that is not, on the whole, more bad than good – despite our dim grasp of the relevant counterfactuals of freedom – then by the same token, we can also say that there is at least one feasible world β that has less evil than, but just as much good as, the actual world.

Reply – We can again break the parallel. Recall the two-step process in arguing for LIFE: firstly, there is a feasible life-abundant world α that God is morally permitted to actualize, and secondly, for all we know, the actual world is that world. The first step seems undeniable: given that God could have created a world consisting of a single person, and that God has at His disposal the entire (probably infinite) array of all possible people, it would be ludicrous to suggest that there is not a single feasible world of free creatures, however small and simple it may be, that is on the whole better than not. Notice that the fewer people there are, the fewer counterfactuals of freedom that God must contend with. The second step then follows in short order from Durstonian complexity arguments.

To follow parallel steps, the proponent of the problem of evil would argue that we know the relevant counterfactuals of freedom well enough that we can say that there is a world β that has just as much goodness as our world, but less evil. But how could they know that? The proponent’s claim is far more substantial than its fine-tuning counterpart because it refers to the amount of good that obtains in the actual world, and the knowledge of counterfactuals of freedom required to make this kind of a judgment is far more extensive than that required to justify the claim that there is a feasible world like α. Much of the goodness of our world comes from the fact that it contains so many people and all that their lives and experiences entail. But then, in arguing that β is feasible, one would have to argue that β contains just as many people as the actual world. To make that claim, one would have to grasp the relevant counterfactuals of freedom to a far greater degree than is required to secure α’s probable existence.

One might think that the proponent of LIFE must also contend that α has just as many people as the actual world, but this is mistaken. They just have to show that there is no reason to think that α does not resemble the actual world in this way. α is more properly construed as the set of all those morally positive, feasible worlds that contain free agents. In step one, we establish that this set is non-empty. In step two, we establish that there is no reason to think that the actual world does not fall within this set. Those two premises are all that the FTA needs.

Consider an analogy. Suppose that one could show that God would likely create purple penguins and further, that such penguins are terribly unlikely if naturalism is true. If we then discover one hundred thousand purple penguins, we will have evidence for God’s existence. Now, suppose someone objects by claiming that all we have shown is that a world with some number of purple penguins or other is likely given theism, not that a world with one hundred thousand such penguins is likely. This would not be a good objection. So long as we have no reason to think that God would not create that many penguins, then grounds for thinking God likely to create some amount or other of these super special penguins will be enough to secure the inference to theism in this case. The same goes for fine-tuning and morally positive worlds with free agents.

Or have I made a misstep? So long as the number of people in the actual world is finite, then given an infinite array of possible people and counterfactuals, it seems just as plausible to suppose that God could have found a way to create a world qualitatively identical to the actual world, but lacking in this or that actual evil, as it does to claim that God could have created a net-positive world with free creatures.Footnote 6 Knowledge of infinite people, circumstances, and counterfactuals connecting them is a tremendous resource for finding a better world than the actual one. Compared to infinity, the counterfactuals determining a world with a single person, and those determining a world identical to the actual one (save for this or that evil), are equally susceptible to the intuition driving my claim that in this vast plenitude of possibility, α surely obtains.

The best way out of this line of attack is to insist that we do not know if the actual world is finite in extent or not. For all we know, there are an infinite number of people in the actual world. If so, then the same broadly probabilistic argument advanced for thinking that α obtains would not in fact support the conclusion that β obtains as well. There has been an explosion of philosophical work on the idea of a theistic multiverse (Blank Reference Blank2018; Climenhaga Reference Climenhaga2018; Kraay Reference Kraay and Nagasawa2012; O’Connor Reference O’Connor2008; Pittard Reference Pittard2023; Reference Rubio and DaeleyRubio forthcoming; Turner Reference Turner and Kraay2015). Such a model posits an infinite array of different universes that God creates. Cosmology and theoretical physics as well are quite open to the idea of a multiverse (Greene Reference Greene2011; Read and Le Bihan Reference Read and Le Bihan2021; Vilenkin and Perlov Reference Vilenkin and Perlov2017). It is at least debatable whether the actual world is finite – in spatial extent, number of universes, or number of people. But if we do not know that the actual world is finite, then we do not know that even graced with an infinite array of possible people and corresponding counterfactuals of freedom, God would be able to create a feasible world with all the good in the actual world, but absent this or that evil. That much is enough to undercut the present objection.Footnote 7

2. Restricted scope

Objection – The conclusion I have reached is not very significant because Durston’s argument only has a chance at undermining a local problem of evil rather than a global problem of evil, a distinction first drawn by van Inwagen (Reference van Inwagen2006, p. 8). A version of the former would be the claim that a particular evil – like E1 – is probably gratuitous, while a version of the latter would be the claim that of all the evil in the world, at least one is probably gratuitous.Footnote 8 In assessing the latter claim, the proponent of Durston’s argument faces a dilemma: either a principle of indifference (or something like it) is applicable to the global evil in the world, or it is not.

If the former, the probability that none of the evil in the world is gratuitous is exceedingly low, even granting that the probability that any particular evil is gratuitous is not low. Tooley (Reference Tooley and Zalta2021) and Plantinga and Tooley (Reference Plantinga and Tooley2008) advance this argument at length, but the details need not concern us because the intuitive point is not hard to grasp. If we ‘assume that unknown [greater goods] and [greater evils] are evenly distributed across [possible] worlds … then the … more prima facie wrong events there are – the smaller the proportion of worlds in which all these events are in fact [not gratuitous]’ (Collin Reference Collin2020, p. 337). To illustrate: if, for any specific evil, the probability that it is not gratuitous is 0.5 (as suggested by the principle of indifference), then the probability that ten such events are not gratuitous is  $\frac{{\text{1}}}{{{\text{1042}}}}$.

$\frac{{\text{1}}}{{{\text{1042}}}}$.

But suppose we opt for the second horn and deny that a principle of indifference is applicable in this way. The advocate of the FTA then ostensibly can no longer affirm a key premise in their argument:

2. The likelihood that a life-permitting universe exists on naturalism is vanishingly small.

The argument for (2) is that we should assume that all possible constants and initial conditions are equally probable, given naturalism. When one then learns that the proportion of life-permitting values is small, it will follow that the probability of life-permitting values obtaining given naturalism is itself small. This reasoning just is the principle of indifference in action. But if we cannot appeal to such principles to assess the probability that the evil in the world is gratuitous, then we cannot appeal to them when arguing for premise (2).

Reply – A bit of reflection absolves the problem. Collin (Reference Collin2020) points out that ‘[i]n treating the possibility space as including all structure descriptions, and weighing these equally, Tooley begs the question against the theist’ (p. 345). How so? Well, simply because the ‘idea that unknown [greater goods] and [greater evils] are assigned to events randomly, or as good as randomly, is something that can only be held if one has already rejected theism’ (p. 344). Tooley has only shown that the probability that all the evil in the world is not gratuitous given naturalism is quite low. But that, of course, is no surprise. Indeed, the advocate of the FTA makes this very point in defending premise (2): given naturalism, the probability that a life-permitting universe would obtain is vanishingly small. A rejection of Tooley-type arguments from evil is consistent with advocating the FTA.

3. Inscrutability

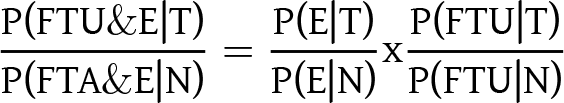

Objection – Consider the sceptical theist’s claim that the likelihood of the evil we observe given theism is inscrutable.Footnote 9 If ‘E’ is the evil in the actual world, ‘FTU’ is a fine-tuned universe, ‘T’ is theism, and ‘N’ is naturalism, then the odds form of Bayes’s Theorem allows us to relate all the relevant likelihoods as follows:

\begin{equation*}

\frac{{{\text{P(FTU}} \& \text{{E|T)}}}}{{{\text{P(FTA}} \& \text{{E|N)}}}} = \frac{{{\text{P(E|T)}}}}{{{\text{P(E|N)}}}}{\text{x}}\frac{{{\text{P(FTU|T)}}}}{{{\text{P(FTU|N)}}}}\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\frac{{{\text{P(FTU}} \& \text{{E|T)}}}}{{{\text{P(FTA}} \& \text{{E|N)}}}} = \frac{{{\text{P(E|T)}}}}{{{\text{P(E|N)}}}}{\text{x}}\frac{{{\text{P(FTU|T)}}}}{{{\text{P(FTU|N)}}}}\end{equation*}This equation belies a simple point: for our total evidence base, FTU and E, to raise the probability of theism against naturalism, the left-hand side of the equation must be greater than 1. But then, given the equation, it follows that we cannot calculate that crucial likelihood. For, per Durstonian ST, P(E|T) is inscrutable, a fact that entails an unfortunate result. Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that P(FTU|T) is 0.1, and let’s grant the sceptical theistic claim that P(E|T) is somewhere in the range (0,1), though we know not where. To calculate P(FTU&E|T), we multiply either end of that range by 0.1. So, the final probability of all our evidence given theism is somewhere in the range (0,0.1). But then, no matter what P(FTU&E|N) happens to be, we could never say that theism is confirmed against naturalism – or against any other hypothesis, for that matter. Even if P(FTA&E|N) were 0.000000000001, the likelihood of that same evidence given theism might, for all we know, be even lower. Nothing about that implication stems from the values we chose above for the other likelihoods involved. As Climenhaga (forthcoming) points out in a discussion of the same problem, ‘taking subsequent evidence into account can change the upper bound of this probability, but not its lower bound’ (sec. 3). The long and short is that once we consider our total evidence base, a base that includes evil as well as fine-tuning, then we cannot say that theism is confirmed against naturalism, even if it might be confirmed in an artificial situation in which we have sectioned off the evil in the world, E, from our evidence pool.

Now, that last point invites the retort that we ought to ignore E when calculating the final probabilities, but the requirement of total evidence demands that ‘when assessing the credibility of hypotheses, we should endeavour to take into account all of the relevant evidence at our disposal instead of just some proper part of that evidence’ (Draper Reference Draper2020, p. 179). To illustrate: does the information that someone has a headache raise the probability that Mark has a headache? It does, even if just a tad. But then suppose that you learn the far more specific information that Donald is the one with a headache. This specific form of the evidence no longer confirms the hypothesis that Mark has a headache. Similarly, does the information that the universe is fine-tuned confirm theism? Well, that’s not really the relevant question; the right thing to ask is, does the information that a fine-tuned universe, filled with all the evil we observe, confirm theism? The answer to that question, as we have seen, is that it does not – or at least, we cannot know if it does or not.

Reply – Notice that this problem does not stem from Durstonian considerations or any arguments for ST whatsoever; the very definition of ST generates the issue. ST entails that we cannot evaluate the likelihood of evil given theism. If one grants that claim, then regardless of the reasons one cites for it, the incompatibility between ST and the FTA asserts itself in the way outlined above. Moreover, the true implication of the problem may be even worse: as Climenhaga (Reference Climenhaga, Buchak and Deanforthcoming) argues, it may be that if we cannot tell how likely evil is given theism, then we cannot tell how likely it is that God exists, full stop, whether our warrant for belief in God derives from theistic arguments or elsewhere. For this reason, the problem of deriving a posterior probability for theism, all evidence considered, is a bigger issue for ST than the one explored in this article. Still, if no response to it is forthcoming, it renders the present investigation beside the point.

Fortunately, it is plausible that Climenhaga’s reasoning has gone wrong somewhere. Consider the following thought-experiment adapted from Joyce (Reference Joyce2010, p. 283).Footnote 10 There is an urn with an unknown number of coins: one, a trillion, a bazillion – for any finite n, there could be n coins. You do know that each coin, however many there are, will have a precise bias, and that it could be anything spanning the full range of propensities – that is, one coin could yield heads one in a million times, another two in a billion times, another three out of five times, another every time, and so on. You also do not know how many of each bias-type coin are in the urn. Someone then randomly draws a coin from the urn and places it next to another coin that you know to be fair. One of these coins is flipped, though you know not which, and it lands heads (call this outcome ‘H’). We thus have two hypotheses to explain this outcome: the urn-coin was flipped (U) or the fair coin was flipped (F). P(H|F) = 0.5. But what is P(H|U)? Plausibly, P(H|U) = (0,1). So, on the basis of the heads outcome alone, you cannot know if the coin flipped was the fair one, or the urn one. That much seems right.

But suppose you then learn something new: your friend Frank claims that he saw the coin being taken out of the urn, flipped, and land heads. This constitutes another piece of evidence (O) – that is, ‘Frank reports seeing that it was the urn coin that was flipped’ – that we can add into the mix. What is P(H & O|F)? Very low, because P(O|F & H) is very low; if the fair coin was flipped and landed heads, it is unlikely Frank would lie about that fact or hallucinate otherwise. But then, what is P(H & O|U)? Well, given the above reasoning, we only know that it falls somewhere within the range (0, m), for some m arbitrarily close to 1 depending on what we take P(O|U & H) to be. But this no longer makes sense; we ought to conclude that the coin flipped was the urn-coin, despite our ‘total evidence base’ preventing us from drawing this conclusion.

I suggest that in cases where some data point is inscrutable on a hypothesis, we ought to ignore it when determining the posterior probability of the hypothesis in question. Consider Cullison’s epistemological principle explored above: evidence that P is not itself evidence that someone else does not have better evidence that ![]() $\sim$P. But does that mean that we should worry about the possible evidence someone might have for

$\sim$P. But does that mean that we should worry about the possible evidence someone might have for ![]() $\sim$P? No. We should base our beliefs on the evidence we have and set concerns about possible epistemic superiors to the side. Similarly, when calculating theism’s posterior probability given all the evidence at our disposal, we ought to set inscrutable data points to the side. But what of the requirement of total evidence? That principle is not obviously pertinent in such a recondite situation as true inscrutability, and a more circumspect requirement that bars inscrutable data does not have any counter-intuitive or absurd implications. It is worth emphasizing how epistemically extreme an inscrutable likelihood of (0,1) is. In ordinary, contexts when a coin of unknown bias is flipped, we have a wealth of background knowledge that reins in the range of the relevant likelihood (it took a lot of stipulating, after all, to get to a scenario close to plausible inscrutability).Footnote 11 It is therefore plausible that we ought to treat scrutable and inscrutable data differently vis a vis a requirement of total evidence.

$\sim$P? No. We should base our beliefs on the evidence we have and set concerns about possible epistemic superiors to the side. Similarly, when calculating theism’s posterior probability given all the evidence at our disposal, we ought to set inscrutable data points to the side. But what of the requirement of total evidence? That principle is not obviously pertinent in such a recondite situation as true inscrutability, and a more circumspect requirement that bars inscrutable data does not have any counter-intuitive or absurd implications. It is worth emphasizing how epistemically extreme an inscrutable likelihood of (0,1) is. In ordinary, contexts when a coin of unknown bias is flipped, we have a wealth of background knowledge that reins in the range of the relevant likelihood (it took a lot of stipulating, after all, to get to a scenario close to plausible inscrutability).Footnote 11 It is therefore plausible that we ought to treat scrutable and inscrutable data differently vis a vis a requirement of total evidence.

Still, I acknowledge that I might be wrong in my proposed connection between inscrutability and total evidence. These are tough issues. If we cannot treat inscrutable data in the way I suggest, I admit defeat in the attempt to reconcile ST with the FTA.

Conclusion

My analysis has returned an important result: every proffered argument for ST either (1) conflicts with arguments for LIFE, or (2) fails to undermine the evidential problem of evil – except for Durston’s argument from the consequential complexity of history. Insofar as we find the latter argument convincing, we can still claim that the probability that God would allow the evil we observe is inscrutable without giving up the FTA. If, however, one (i) does not find Durston’s case persuasive or (ii) demands that inscrutable data feature into one’s final evaluation of theism, then the theistic philosopher must either reject the FTA or else mount an attack on the problem of evil that is independent of sceptical theistic considerations. Given the widespread popularity of both ST and the FTA, I take this to be a significant conclusion.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Graham Doke, Ho-yeung Lee, Mark Wynn, Michael C. Rea, Saad Ismail, and two anonymous reviewers for comments on the manuscript. Only God knows for sure how things would have gone without their input - though I suspect not well.

Financial support

The author did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work and the author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.