Introduction

Approximately one in every five youth are bullied by their peers (U.S. Department of Education, 2016), and extensive research highlights the deleterious effects of bullying on victims’ mental health, physical health, and academic outcomes (Juvonen & Graham, Reference Juvonen and Graham2014; Wolke & Lereya, Reference Wolke and Lereya2015). Communicating the severe consequences of bullying to the public may be essential for the promotion of appropriate policy changes and program development. Indeed, framing scientific findings in ways that engage key public stakeholders can catalyze important translational efforts (Bubela et al., Reference Bubela, Nisbet, Borchelt, Brunger, Critchley, Einsiedel and Jandciu2009), and past research suggests that people are more supportive of public action towards pressing social issues (e.g., childhood obesity) if they are framed in terms of their health consequences (Gollust et al., Reference Gollust, Niederdeppe and Barry2013). However, very little is known about public perceptions of bullying or whether framing bullying as a health risk promotes greater support for the development and implementation of anti-bullying policies. Learning about the health burden of bullying on victims may be one powerful method of highlighting its severity and garnering greater support for anti-bullying initiatives.

Objective

The goal of the present study was to evaluate the influence of “bullying messaging” on young adults’ support for anti-bullying policies. Understanding whether certain framing strategies promote greater anti-bullying support is important for translational efforts seeking to bridge bullying research and policy. Specifically, the study tests whether emphasizing the negative health consequences of bullying—as opposed to underscoring its prevalence or educational impact—promotes greater support of programs and policies designed to reduce bullying among youth. As an exploratory aim, this study also examines young adults’ relative levels of support for different types of anti-bullying policies (e.g., federal laws versus school-based interventions).

Methods

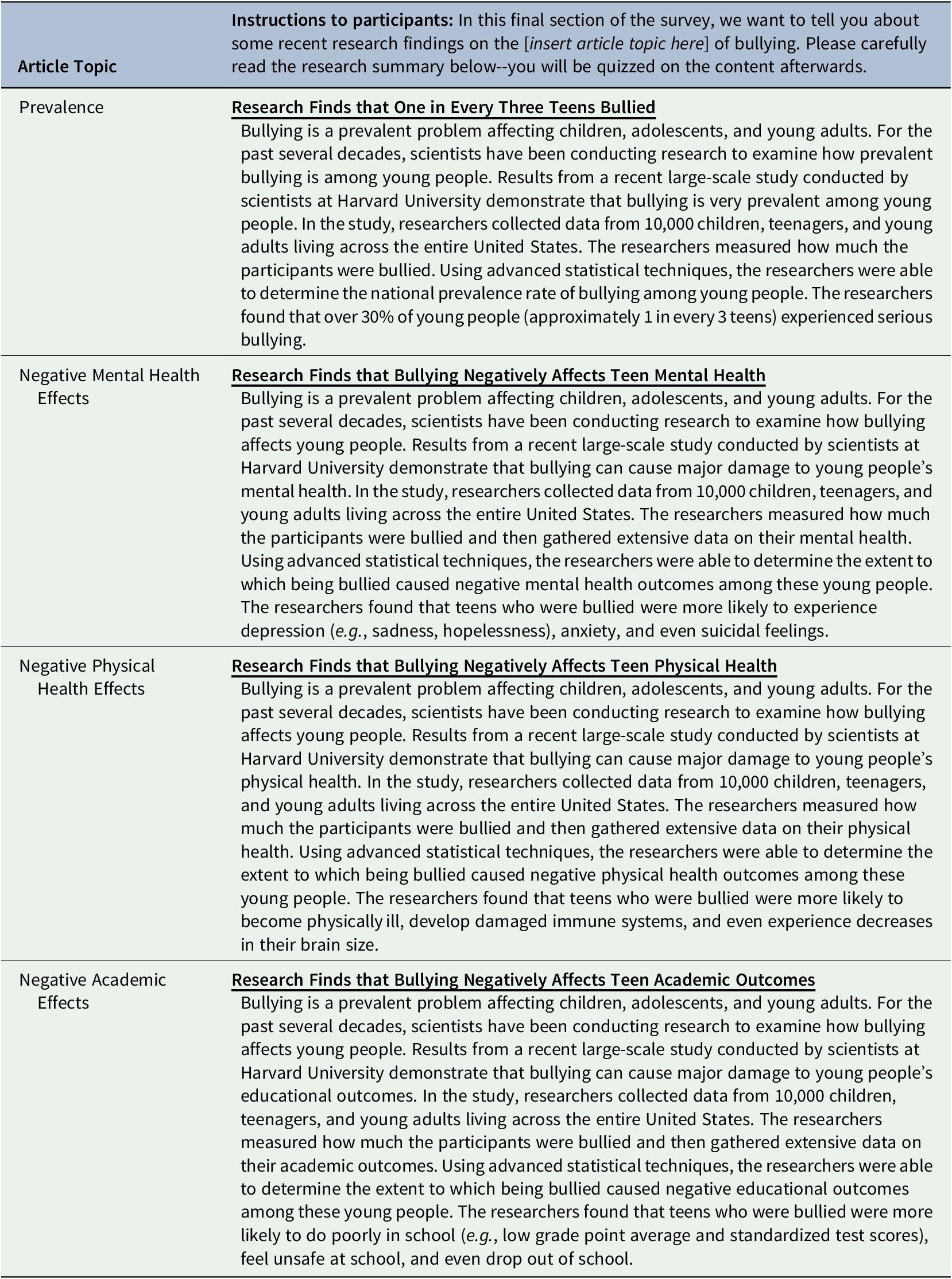

Procedures were preregistered as part of a larger study protocol on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/75vng), and data analyzed for the current study can be found at https://osf.io/t5fzv/. Participants (n = 350) between the ages of 18 and 25 were recruited via online advertisements from an undergraduate psychology subject pool at a large, urban university in the midwestern United States and received course credit for participating. All procedures were approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board. The current study focuses on an analytic sample of 329 participants (82% female; 45% White/European American, 22% Middle Eastern/North African, 13% South Asian, 7% Black/African American, 6% Multiethnic/Biracial, 3% Latinx, 5% Other) who completed the full experimental procedure. At the end of an online survey, participants were randomly assigned to one of four conditions in which they read a brief passage summarizing findings from an ostensible large-scale research study on bullying that was made up for the experiment (see Table 1). After reading the research summary, participants rated how much they supported six different anti-bullying policies (items adapted from Gollust et al., Reference Gollust, Niederdeppe and Barry2013) using a Likert-scale ranging from 1 (strongly oppose) to 5 (strongly support). Ratings from the six items were averaged to create a mean score of anti-bullying policy support, with higher scores indicating greater support for anti-bullying programming (α = 80).

Table 1. Experimental conditions varying in bullying messaging.

Results

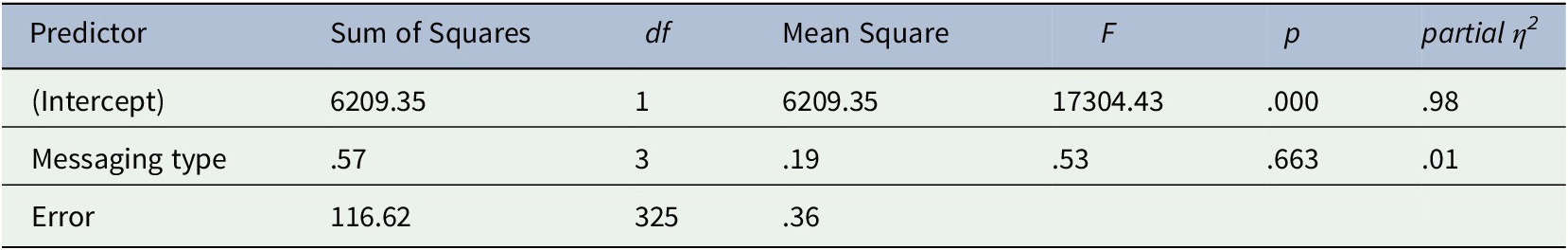

Table 2. Results from one-way between-subjects ANOVA comparing average levels of anti-bullying policy support by experimental condition.

Confirmatory analyses (i.e., testing preregistered hypotheses) were conducted using a one-way between-subjects ANOVA to compare average levels of anti-bullying policy support by experimental condition. There were no significant differences in policy support across conditions (see Table 2). Average support for anti-bullying policies was relatively high, regardless of whether the article emphasized prevalence (M = 4.40, SD = .54), mental health effects (M = 4.30, SD = .69), physical health effects (M = 4.37, SD = .52), or academic effects (M = 4.31, SD = .64).

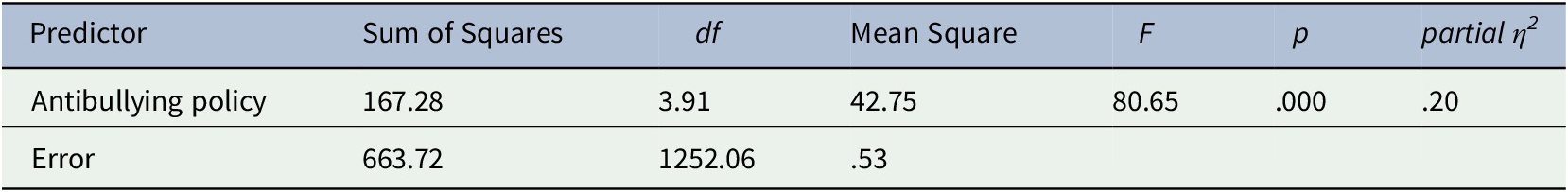

Table 3. Results from one-way repeated-measures ANOVA comparing item-level mean differences for each type of anti-bullying policy collapsed across conditions.

Note. Values reflect results with a Greenhouse–Geisser correction.

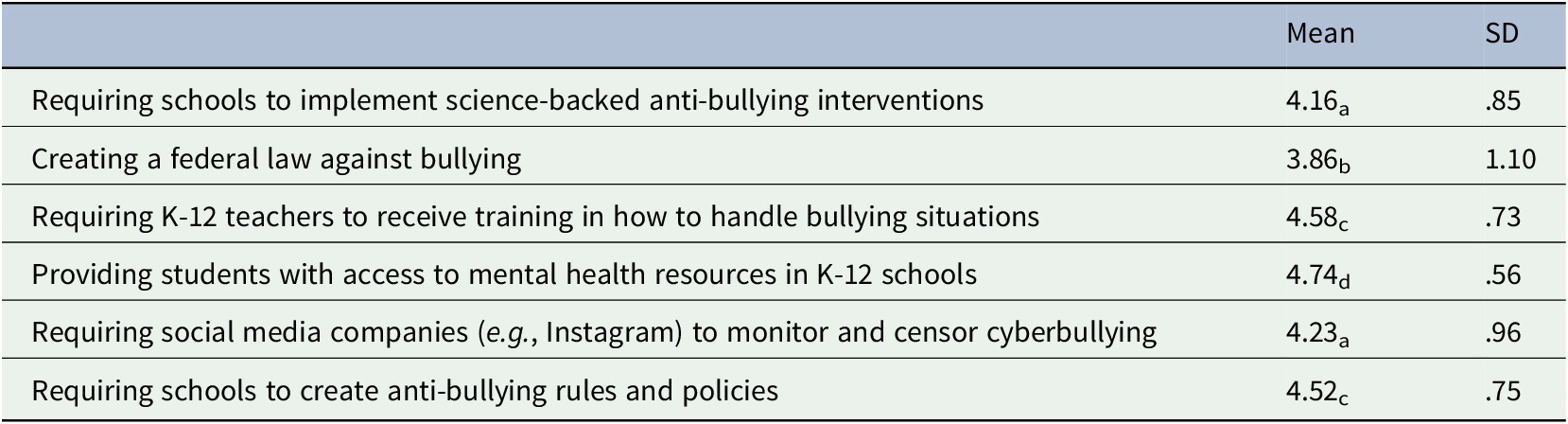

Exploratory analyses (i.e., testing non-preregistered hypotheses) were conducted using a repeated measures ANOVA to examine item-level mean differences for each type of anti-bullying policy collapsed across experimental conditions. Results indicated significant within-person differences in endorsement of the six policies (see Table 3). Pairwise comparisons with a Bonferonni correction showed that participants endorsed the highest levels of support for making mental health resources available to students in K-12 schools and the lowest levels of support for creating a federal law against bullying (see Table 4).

Table 4. Item-level means and standard deviations for anti-bullying policy support.

Note. Non-shared subscripts indicate significant mean-level differences between items. All denoted differences significant at p < .001 after Bonferroni correction.

Discussions

The results suggest that strategically framing messages about bullying around health risk, as opposed to prevalence or academic impact, does not increase young adults’ support for anti-bullying policies. Results from exploratory analyses also highlighted young adults’ perceived importance of K-12 mental health resources for bullied youth, regardless of messaging type. Limitations include the reliance on a convenience sample of predominantly female college students, restricting the generalizability of the results. For example, the null findings may reflect some degree of developmental specificity (Bradshaw et al., Reference Bradshaw, Sawyer and O’Brennan2007) and corresponding ceiling effects. The current sample of young adults have grown up in a world where bullying is more widely recognized as a serious public health issue (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016), and, across conditions, most participants agreed or strongly agreed with all six policy suggestions. Bullying messaging type could have stronger effects on the policy opinions of older adults, who may exhibit greater variability in their perceptions of bullying and its broader societal significance. Replication of results among a nationally representative sample would provide important insights into the robustness of the current findings.

Conclusions

The current results did not support the hypothesis that health-related bullying messages would resonate more than non-health-related bullying messages. However, the findings also provide some encouragement by revealing high overall support for anti-bullying policies, at least as endorsed among young adults. Future research should consider whether there are differences in bullying framing effects among different age groups (e.g., younger versus older adults) and as a function of individuals’ peer histories.

Funding information

None to report.

Disclosure statement

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

The data used in this study are available from https://osf.io/t5fzv/

Comments

Comments to the Author: Although the paper offers a novel insight into the implications of how bullying is framed, there is greater depth required to justify the importance of this within the article. My advice to the author is to build the real world application/importance of framing bullying from a health perspective and embed this specifically within the population under study. The author would also benefit from building theoretical content in the introduction section for which to explore in the discussion section of the report. There is a disjoint between the theoretical discussion points raised and the material provided in the introduction. The title would benefit from reflecting the study outcomes, despite non-significant results as opposed to opening a question – this is misleading. In addition, the abstract should clearly state the aims in the opening section. It is not until the introduction section that I was clear about the aims of the research.