Article contents

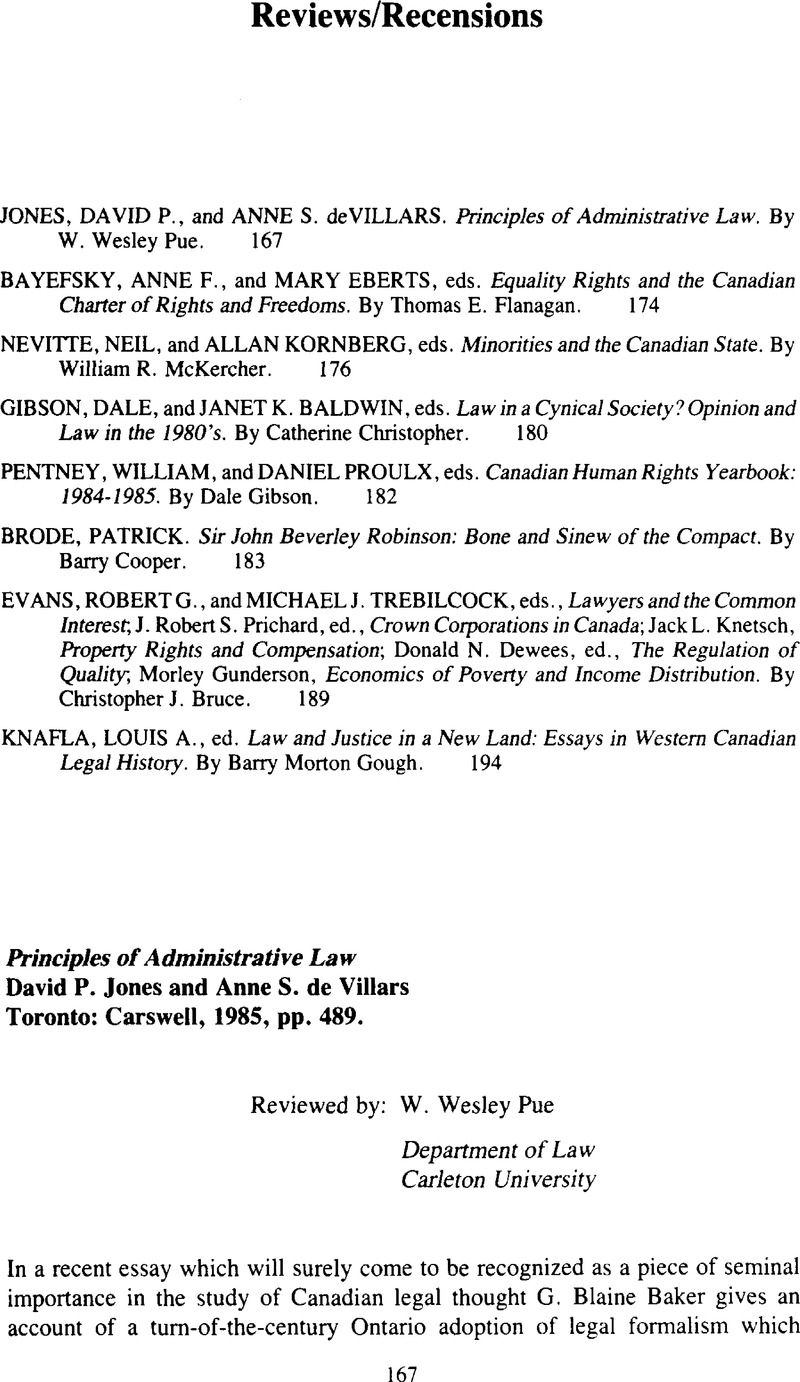

Principles of Administrative Law, David P. Jones and Anne S. de Villars, Toronto: Carswell, 1985, pp. 489.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 July 2014

Abstract

- Type

- Reviews/Recensions

- Information

- Canadian Journal of Law and Society / La Revue Canadienne Droit et Société , Volume 1 , 1986 , pp. 167 - 174

- Copyright

- Copyright © Canadian Law and Society Association 1986

References

Notes

1. Baker, G. Blaine, “The Reconstitution of Upper Canadian Legal Thought in the Late-Victorian Empire,” Law and History Review 3 (1985), 219–292CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

2. Ibid., 276.

3. Ibid., 277.

4. See Risk, R.C., “Sir William Meredith: The Search for Authority,” Dalhousie Law Journal 7 (1983), 713Google Scholar.

5. Mullan, David J., Administrative Law (2nd ed.; Toronto: Carswell, 1979)Google Scholar.

6. Most of my criticisms here would, moreover, apply Mutatis Mutandis to my own previous work in administrative law, Natural Justice in Canada (Vancouver: Butterworths, 1981)Google Scholar Mea culpa!

7. “Society” is itself a notoriously difficult and problematic concept. See, for example, Rock, Paul, “The Sociology of Deviancy and Conceptions of Moral Order,” British Journal of Criminology 14 (1974)CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

8. Jones, & de Villars, , Principles of Administrative Law, Preface, viiGoogle Scholar.

9. Ibid., 435.

10. U.S. Supreme Court: “Here is the Law at its best … ” See Note 12.

11. Appreciation of this is not restricted to “realist” scholars. See, e.g., Hart, H.L.A., The Concept of Law (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1961), 11–13Google Scholar; Fuller, Lon, The Problems of Jurisprudence (Brooklyn: Foundation Press, 1949, temporary edition)Google Scholar.

12. One U.S.A. legal scholar had the following to say about that country's experience of constitutional decision making in the U. S. Supreme Court: “Here is the Law at its best; here are lawyers at their most distinguished, their most powerful. Still comparing piles of abstract, indecisive, and largely irrelevant principles as though they were matching pennies on a street corner. Still draping in the longiloquent language of a generalized logic the answers — some good, some bad — to specific social problems. And purporting all the while to be applying the commands and prohibitions of the U.S. Constitution. No wonder Charles Evans Hughes, long before he became the Supreme Court's Chief Justice, once blurted out with a bluntness that is rare in lawyers:- ‘We are under a Constitution, but the Constitution is what the judges say it is.’” (Rodell, Fred, Woe Unto You, Lawyers! (New York: Berkeley Books, 1980), 63–64.Google Scholar)

13. See, for example, Goode, M.R., “Law Reform Commission of Canada — Political Ideology of Criminal Process Reform,” Canadian Bar Review (1976), 653–674Google Scholar; Reasons, Charles and Rich, Robert, The Sociology of Law: A Conflict Perspective (Toronto: Butterworths, 1978)Google Scholar; Cotterrell, Roger, The Sociology of Law (London: Butterworths, 1984)Google Scholar; Kairys, David (ed.), The Politics of Law (New York: Pantheon Books, 1982)Google Scholar. Two excellent and helpful books are Harris, Phil (ed.), An Introduction to Law (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1984)Google Scholar; and O'Malley, PatLaw, Capitalism and Democracy (Sydney: George Allen & Unwin, 1983)Google Scholar. An especially effective critique of consensus theory is to be found in Liddle, Mark, “Book Review: The Canadian Legal System,” by Gall, Gerald L., Canadian Criminology Forum 4 (1982), 166Google Scholar. An emphasis on the spatial manifestation of dissensus is a relatively new and enormously promising addition to the literature. A review of this nascent literature and a proposed research agenda is to be found in Economides, Kim et al. , “The Spatial Analysis of legal systems — Towards a Geography of Law” (University of Exeter: A.J.R.B.P., Working Paper No. 3, 1985)Google Scholar. Lawyers do seem to cling with unusual tenacity to simple consensus models: See Abella, Rosalie, “Canada's Judges and Public Policy: Implications of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms” (John Porter Memorial Lecture, Carleton University, 1985)Google Scholar.

14. The literature here is enormously complex. Introductory treatments are found in Harris An Introduction to Law, O'Malley, Law, Capitalism and Democracy and Cotterrell The Sociology of Law. See also Greer, Edward, “Antonio Gramsci and ‘Legal Hegemony’” in Kairys, , The Politics of LawGoogle Scholar; Thompson, John B., Studies in the Theory of Ideology (Oxford: Polity Press, 1984)Google Scholar; and Sumner, Colin, Reading Ideologies (London: Academic Press, 1979)Google Scholar. A classic explanation of the ideological role of law is to be found in Hay, Doug, “Property, Authority and the Criminal Law,” in Hay, Linebaugh and Thompson, , Albion's Fatal Tree (London: Allen Lane, 1975)Google Scholar. Also see Craven, Paul, “Law and Ideology: The Toronto Police Court 1850-1880,” in Flaherty, (ed.), Essays in the History of Canadian Law, Vol. II (Toronto: Osgoode Society, 1983)Google Scholar. A useful Canadian source, though one which does not deal with law in particular, is Marchak, M. Patricia, Ideological Perspectives on Canada (Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson Ltd., 1981)Google Scholar. In addition, most introductory books on law in society now deal with both simple conflict perspectives and theory of ideology. The literature is too immense and fast-developing to deal with fully in a note.

15. Again, the literature is immense. Some important studies include Olsen, Dennis, The State Elite (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Ltd., 1980)Google Scholar; Griffith, J. A.G., The Politics of the Judiciary (Glasgow: Fontana, 1977)Google Scholar; Miliband, Ralph, The State in Capitalist Society (London: Quartet Books Ltd., 1973)Google Scholar; Miliband, Ralph, Capitalist Democracy in Britain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984)Google Scholar; Cain, Maureen, “Necessarily Out of Touch,” in Carlen, P. (ed.), Sociology of Law (Staffordshire: University of Keele, 1976)Google Scholar; Tate, C. Neal, “Paths to the Bench in Britain,” Western Political Quarterly, 28 (1975), 108CrossRefGoogle Scholar. Paterson, A., “Becoming a Judge,” in Dingwall, R. and Lewis, P. (eds.), The Sociology of the Professions (London: MacMillan, 1983)Google Scholar; Stevens, Robert, Law and Politics: The House of Lords as a Judicial Body 1800-1976 (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1979)Google Scholar. A valuable historical treatment is to be found in Duman, Daniel, The Judicial Bench in England, 1717-1875 (London: Royal Historical Society, 1982)Google Scholar. An invaluable though non-critical Canadian study of Supreme Court Appointments is Snell, James G. and Vaughan, Frederick, The Supreme Court of Canada: History of the Institution (Toronto: Osgoode Society, 1985)Google Scholar.

16. The words in quotation marks in this sentence are intended to be representative of treatise apologetics generally and are not direct quotations from Principles of Administrative Law. See, however, the preface to that book.

17. Galanter, Marc, “Why the ‘Haves’ Come out Ahead: Speculation on the Limits of Legal Change,” Law and Society Review 9 (1974), 95CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

18. [1925] A.C. 578. See the discussion in Keith-Lucas, B., “Poplarism,” Public Law 52 (1962)Google Scholar.

19. [1982] 2 W.L.R. 62. See the discussion in Pannick, D., “The Law Lords and the Needs of Contemporary Society,” Political Quarterly (1982), 318Google Scholar.

20. This case, holding it to be “unreasonable” to pay women the same wages as men performing the same work, is passed over with the following comment in Principles of Administrative Law: “Examples where the courts have struck down a delegate's actions on the ground that they were being taken for an unauthorized purpose include: the payment by a municipal council of higher wages than necessary in order to be a model employer even though the council was entitled to pay ‘such wages as [council] may think fit’….” (122).

21. Arthurs, H.W., “Rethinking Administrative Law: A Slightly Dicey Business,” Osgoode Hall Law Journal 17 (1979), 1Google Scholar.

22. McAuslan, P., “Administrative Law, Collective Consumption and Judicial Policy,” Modern Law Review 46 (1983), 1CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

23. Griffith, J.A.G., “Constitutional and Administrative Law,” in Archer, P. and Martin, A. (eds.), More Law Reform Now (London: Barry Rose, 1983)Google Scholar.

24. Pannick, “The Law Lords.” See also Prosser, T. “Towards a Critical Public Law,” Journal of Law & Society 9 (1982), 1CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

25. Jones, and de Villars, , “Principles of Administrative Law,” 437Google Scholar.

26. Ibid., 426.

27. Contrast H.W. Arthurs, “Rethinking Administrative Law”; Arthurs, H.W., “Special Courts, Special Law: Legal Pluralism in the 19th Century,” in Rubin, G.R. and Sugarman, David (eds.), Law Economy & Society (Abingdon: Professional Books, 1984)Google Scholar; Arthurs, H.W. ‘Without the Law’: Administrative Justice and Legal Pluralism in Nineteenth Century England (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1985)Google Scholar; Sugarman, David, “The Legal Boundaries of Liberty: Dicey, Liberalism and Legal Science,” Modern Law Review 46 (1983), 102Google Scholar.

28. Harris, , An Introduction to Law, 306Google Scholar. A considered overview of issues of institutional competence is found in Komesar, Neil K., “Taking Institutions Seriously: Introduction to a Strategy for Constitutional Analysis,” University of Chicago Law Review 51 (1984), 366CrossRefGoogle Scholar. One of the best scholarly treatments of such issues is to be found in Glasbeek, H.J. and Mandel, M., “The Legalization of Politics in Advanced Capitalism: The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms,” Socialist Studies 2 (1984), 84Google Scholar.

- 1

- Cited by