The most important psychiatric implication of experiencing trauma during war is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The core symptoms of PTSD are intrusive re-experiencing of traumatic events, hyperarousal in reaction to minor stimuli and avoidance of trauma-related triggers. In this paper we describe the phenomenon of intrusive re-experiencing, of which the post-traumatic nightmare (PTNM) is an impressive manifestation that causes considerable distress (Reference Mellman, Kulick-Bell and Ashlock et al, 1995; Reference SchreuderSchreuder, 1996; Reference Ørner and de LoosØrner & de Loos, 1998; Reference Schreuder, van Egmond and KleijnSchreuder et al, 1998).

Post-traumatic nightmares are difficult to study because it is often unknown if and when they will occur. Some physical manifestations can be studied in sleep laboratories (although successful recordings are scarce), but researchers are dependent mostly on the subjective reports of patients. However, the striking and anxiety-provoking content of nightmares usually means that they are better remembered than normal dreams (Box 1).

Box 1. The study of nightmares

A nightmare is better recalled than a normal dream because it is striking and anxiety-provoking

Clinical reports of nightmares are both subjective and retrospective

Sleep-laboratory studies are scarce because:

-

• nightmares tend to disappear in the laboratory setting

-

• nightmares occur unpredictably

Box 2. Terminology

Dream mental activity during sleep

Nightmare a frightening dream from which the sleeping person instantly wakes up

Anxiety dream a frightening dream that does not immediately awaken the sleeping person, but which is remembered on waking in the morning (or after the major sleeping period)

Post-traumatic used to indicate that a person associates the contents of his/her dreams with traumatic events experienced in the past

PTNM post-traumatic nightmare

PTAD post-traumatic anxiety dream

Another problem is the course of nightmares following a traumatic experience. Many people suffer from nightmares directly after a shocking experience, but in most cases their frequency decreases within 6 weeks or so. The majority of people will not go to their general practitioner if they suffer from a nightmare just once a month or less. However, for unknown reasons the frequency may increase suddenly, even years after the traumatic experience, and people who have not previously suffered from PTNMs may start to experience them. PTNMs can trigger PTSD (Reference Schreuder, van Egmond and KleijnSchreuder et al, 1998). Finally, PTNMs can hinder the elaboration of the emotional significance of traumatic experiences in psychodynamic as well as in cognitive psychotherapy of PTSD (Reference Shalev, Galai and SpencerShalev et al, 1993). For these reasons, frequent PTNMs need to be treated.

We do not know why nightmares occur after trauma, nor do we understand the underlying pathogenesis. For example, are the nightmares related to the patient's strategy for coping with a traumatic experience? Owing to this inadequate understanding, current treatment addresses symptoms and is based on clinical experience.

Centre ′45, the Dutch national centre for treatment and research in the psychological trauma of war and violence, is running a research programme studying PTNMs in Western and non-Western societies and patients. The research concentrates on the phenomenological characteristics, rather than the content, of the nightmares. This approach has the advantage that PTNMs can be seen from the perspective of sleep physiology and that we are less dependent on subjective accounts of content that might be altered by waking thinking. It also avoids the problems of culture-specific interpretation of content. This does not mean that we refrain from studying content entirely, or that we exclude cultural perspectives. On the contrary, we are interested in the way in which people from non-Western cultures cope with these disturbing phenomena. But the emphasis is on formal and structural characteristics. We discuss below findings of our own and others' studies in order to formulate guidelines for treatment.

Dutch studies

Several studies conducted by our research group have analysed intrusive memories of war trauma (Reference Schreuder, van Egmond and KleijnSchreuder et al, 1998,Reference Schreuder, Kleijn and Rooijmans2000). These studies focused on the reoccurrence of PTNMs many years after the trauma, considering, among other things, prevalence data, phenomenology, course and the relationship with the traumatic experiences. Participants (both psychiatric patients and non-patients) included Holocaust survivors, Dutch people interned in Japanese camps in Indonesia during the Second World War and Dutch veterans of the First World War, the Dutch–Indonesian war (1945–1949) and several UN peace-keeping interventions.

The prevalence of PTNMs in the groups of patients who had suffered from psychological trauma many years previously (often more than 40 years ago) was high. On the contrary, a very low prevalence was found, in general, in the non-patient groups. A frequency of more than one PTNM per week was recorded in 56% of the patients (Reference Schreuder, Kleijn and RooijmansSchreuder et al, 2000). There was no difference in prevalence between men and women. Patients with PTNMs, even those not diagnosed with PTSD, had significantly more psychiatric complaints than patients without PTNMs. This might explain why the occurrence of nocturnal re-experiencing is often underestimated when based only on the diagnosis of PTSD. People with PTNMs had more, and more severe, post-traumatic complaints; also, they more often had a lower level of psychological and related physical functioning than individuals without PTNMs. Disruption of their sleeping pattern must be taken into consideration. People who have PTNMs appear to have more difficulty falling asleep and sleep for shorter periods than those without PTNMs.

Analysis of PTNMs confirmed clinical reports and earlier research (Reference Van der Kolk, Blitz and Winthropvan der Kolk et al, 1984) that they often contain exact replications of the original traumatic events. Such nightmares are called ‘replicative’ to indicate that, according to the subject, the re-experience is an accurate reproduction of the event. In other words, the place, the people, the time, date and sequence of events are the same as in the original traumatic experience. It should be emphasised that this does not inform us in any way about possible underlying memory processes. The memory of the event plays an important role in re-experiencing. It is unlikely that a traumatic experience will be remembered as accurately as seems to be the case in replicative nightmares (Reference Lansky and BleyLansky & Bley, 1995). However, models derived from animal behaviour studies of fear conditioning show that ‘traumatic memories’ seem to be ineradicable (Reference LeDoux, Xagoraris and RomanskiLeDoux et al, 1989). In studying the phenomenology of PTNMs it may be possible to relate these symptoms to psychodynamics and sleep neurophysiology.

These findings led to a differentiation between two types of PTNM: the ‘symbolic’ and the ‘replicative’ (Box 3). In the symbolic PTNM the dream content has the characteristics of a normal dream. In other words, while there may be elements in the dreams that can be ascribed to traumatic experiences, they are present in a changed form and appear alongside representations of more recent events. So, for instance, the dream may be set in the same place as the original traumatic event, but the people in the dream come from more recent memories and were not there at the time. Other examples of the distortions we find in normal dreams include the merging of different events and impossible leaps in time and space.

Box 3. Types of post-traumatic nightmare

Symbolic nightmares

Content as a normal dream, with distortions, irrational structure and numerous, eidetic images

Related to rapid eye movement (REM) sleep

As ‘normal’ nightmares

Replicative nightmares

Content seems to be a replication of (part of) traumatic experience

Content is logical, more similar to normal thinking

Autonomic arousal is much more pronounced and similar to sleep terror in children

Related to non-REM sleep

Accompanied by motor activity

Response resembles a panic attack

In the replicative PTNM, the dream content does not show the distortions characteristic of normal dreaming. On the contrary, an experience is relived as if it were happening again, and the dreamer may act as if it were happening in real life. Often, but not always, replicative PTNMs are accompanied by manifestations of hyperarousal such as palpitations, increased respiration and excessive sweating. This hyperarousal is similar to that experienced in extreme fear.

Anyone observing this behaviour may have the impression that the person dreaming is suffering from psychosis or other mental illness, which may distress, alarm or even panic them. In some cases, partners have to sleep separately because PTNMs may cause the dreamer to act aggressively.

Dreams, nightmares and PTNM

Replicative PTNMs show remarkably little resemblance to ‘ordinary’ nightmares and anxiety dreams, but seem more related to such phenomena as the night terror and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavioural disorder. The night terror is a disorder of awakening from deep sleep. It may occur in children as part of their maturation process. It is seen in adults less frequently. The classic symptoms of the night terror are a sudden awakening, marked by a loud scream and followed by confusion, disorientation, automatic acting, sleepwalking and motor activity lasting from a few minutes up to half an hour. The hyperarousal in the night terror is comparable to the human response in extreme fear and very similar to that found in replicative PTNM. However, the dream account differs. In the case of night terror, the dream account seems considerably shorter, if there is one at all, and children appear rarely to have recollection of it. Night terror is closely related to nocturnal enuresis, somnambulism and somniloquism, which together are seen as arousal disturbances from slow-wave sleep (Reference BroughtonBroughton, 1968).

The REM sleep behavioural disorder (Reference Schenck, Bundlie and EttingerSchenck et al, 1986) is another phenomenon related to PTNMs. This disorder involves the acting out of dreams through motor activity, which may sometimes be harmful to the individual or to his or her partner. Clinical descriptions of these patients correspond with accounts of PTNM. Because muscle atonia is normal during REM sleep, it is hypothesised that in REM sleep behavioural disorder there is a dissociation of different sleep mechanisms.

The hyperarousal in PTNM resembles the nocturnal panic attack. Hyperarousal attacks during the day are very similar to panic attacks and might be the same phenomenon. Unfortunately, data about nocturnal panic attacks are scarce.

It is widely believed that PTNMs are universal, although this has never been examined.

Mozambique study

In 1997 research was carried out among the population of some small villages in the district of Gorongosa in the Province of Sofala, Mozambique. This specific location for the research was chosen for several reasons. First, Mozambique had been involved in an 18-year civil war, which had ended in 1992. The armed civil conflict had been centred on this region, because both parties had located their troops there, and there had been heavy fighting for almost the duration of the war. Second, mental health care was at a minimal level in this region, which meant that concepts such as psychological trauma and PTSD were unknown to the people. Traditional ways of healing were still widely embedded in the society.

Through one of our team (V.I., an inhabitant of Mozambique) we were able to make contact with the local authorities for permission to carry out this study. The help of a local inhabitant is a sine qua non and invaluable for the success of such a difficult research project. In fact, the difficulties of carrying out such research are as interesting as the results obtained. These difficulties not only threw light on the differences between the context and treatment settings of the psychological consequences of war in Western and non-Western societies. They also emphasised the limitations of Western research methods in settings that greatly differ from those in Western societies. We will give some examples of this.

Because of the lack of phenomenological studies in non-Western societies, we started with a study of the prevalence and phenomenology of post-traumatic nightmares. Therefore, we asked people whether they suffered from nightmares and we studied the traditional way local healers treat these phenomena. Our hypothesis was that nightmares are universal. However, we are cautious about the interpretation of our results. First, our way of asking about nightmares was influenced by our experience from Western societies. Second, our questions were posed in a style determined by a Western frame of reference. That means that we asked for complaints and symptoms from a nosological perspective, and used terminology related to Western concepts of psychopathology.

In the region of our study, dreams and nightmares have more impact on the way people think about and organise their daily lives and plan the future than in Western societies. The most important aspect of this is the way in which people think about themselves, their living family and their ancestors. Ancestors are part of everyday life and respect for their ancestors motivates people's thinking and behaviour. Traditional healers believe that dreams perform various functions. They are used for diagnosis, i.e. through the dream contents the healers can establish the relationship between the aetiology of physical symptoms and the appropriate intervention to apply. Dreams are also conceived as a way in which people get information about their relationships with their ancestors. For example, bad dreams might be taken as a sign that a person had not behaved in a respectful way with regard to an ancestor. Nightmares might be attributed to the spirits of family members who could not (owing to the war) be properly buried or who had been offended, for example, when their graves had been disturbed by people hiding in the graveyards during fighting. Thus, (bad) dreams are often seen not so much as disturbing phenomena intruding into the mind; rather, they are interpreted in a meaningful context of the behaviour of the dreamer.

In their report on the demobilisation of Mozambican soldiers, Dolan & Schafer (1997) described ‘traditional’ rituals and ceremonies for ex-combatants to reconnect them with civilian life. After the demobilisation process the ex-combatants visit the traditional healer (curandeiro), who washes their bodies to free them from bad spirits that persecute them in their dreams. It is believed that bad spirits are a consequence of killing innocent people. The ceremonies can also clean the body of memories of the war, and they mark the transition from military to civilian life. Our study in Gorongosa showed that these rituals and ceremonies are seen not as a healing mechanism, but as a preventive action. The ex-combatants visited the healers to prevent the things they had seen and experienced during the war from returning to their heads and hearts and interfering in their civilian lives.

Often, the interventions of traditional healers are aimed at restoring people's bonds with their families and ancestors. Some traditional healers made a distinction between bad dreams containing some indication of what might happen in the future and bad dreams about past war experiences. The healers reported that the latter are very resistant to treatment. This seems to be in line with findings from Western mental health care: nightmares as a symptom of PTSD are treatment resistant. It was interesting to see that some interventions by the healers were similar to the kinds of intervention in the Western practice of family therapy.

Another point of interest was the translation of our Western-based interviews into the local language. Important words as “anxiety”, ”fear” and “suspicion” were difficult to translate. The local language has many synonyms for these words, each with slightly different meanings. Furthermore, the English words were not always understood by the translators and interpreters. The interviews were conducted by an interviewer who spoke the official language of the country (Portuguese) in the presence of an interpreter who spoke the local language. One also has to keep in mind that the translators and interpeters might themselves have been traumatised by war experiences. Their own tendency to avoid war memories might have made it difficult for them to translate some of the questions or interpret answers accurately.

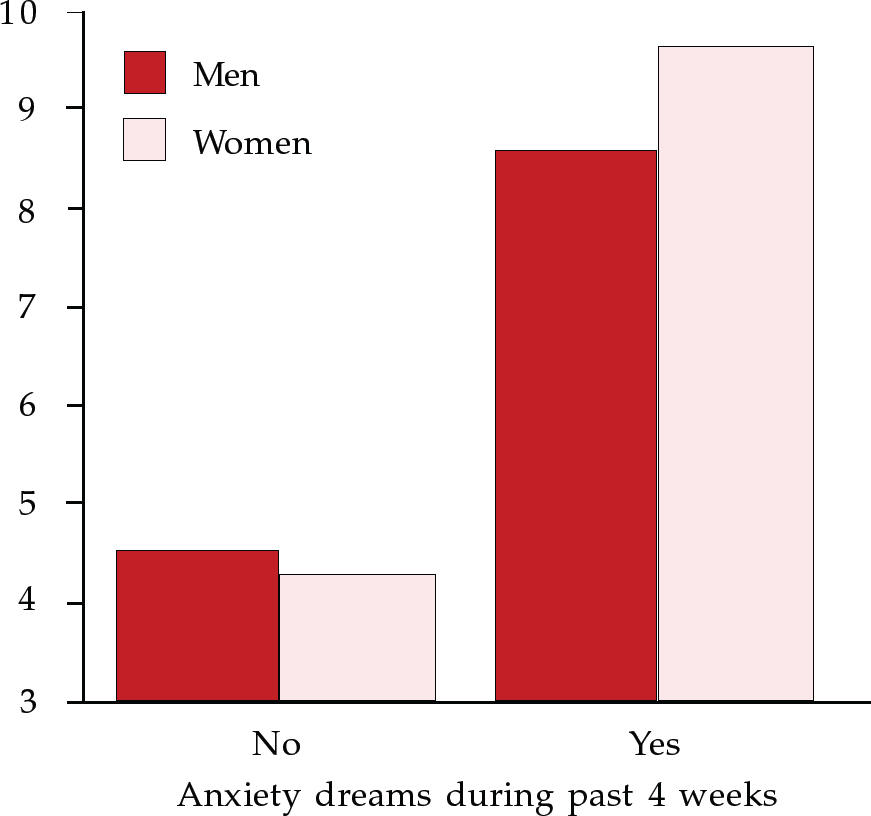

In a cross-sectional design, data were collected in one semi-structured interview per person. In the interviews people were asked about their memories of war (PTNMs included) and about their physical and psychological well-being. Of the study group (n=406), 63% (n=257) suffered from bad dreams. Of these 257 people, almost everyone (97%) was able to recall the content of the dreams. Almost half of this group (47%) experienced their nightmares as a replication of experiences they went through during the war. The accounts they gave resembled replicative PTNMs. Symptoms of hyperarousal were reported at various frequencies: perspiration, 24%; palpitations, 71%; tightness of the chest, 90%. Motor activity during nightmares was reported by 32%, while 82% experienced a feeling of paralysis on waking from them. This latter finding might indicate that the nightmare originated in REM sleep. Interestingly, the number of daytime repetitive thoughts related to traumatic war experiences was quite high, at 48%. Psychiatric morbidity was measured using the Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ), which was originally designed by the World Health Organization's Collaborative Studies for Extending Mental Health Care as a research instrument in a two-stage case-detection procedure (Reference Harding, De Arango and BaltazarHarding et al,1980). It was tested in Ethiopia and found of greatest value in population surveys aimed at estimating the presence of mental disorders (Reference Kortmann and Ten HornKortmann & Ten Horn, 1988). In our study a significant difference (t=12.12, P <0.001) on mean SRQ scores was found between people with and those without PTNMs (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Self-reported symptoms and anxiety dreams experienced by Mozambicans during the past 4 weeks

Five years after the end of the civil war in Mozambique, a high prevalence of PTNMs was found in a random sample of the population in one of the areas of heavy fighting. The phenomenological characteristics of the PTNMs recorded here, such as replication and hyperarousal, closely resemble those found in PTSD patient cohorts in Western societies. However, the way the Mozambican sample coped with post-traumatic symptoms is completely different from common Western treatment strategies.

Theoretical considerations

Currently, diagnostic procedures, instruments and treatment measures for PTSD are based on Western models and designed correspondingly. Some global pathogenic mechanisms have been identified and a number of Western-oriented treatment protocols have been developed that are successful in many cases. However, persistent symptoms such as post-traumatic re-experiencing are poorly understood. These symptoms may remain for a very long time or may occur or return after many years. Thus, data about individual adaptation to shocking war experiences are useful and necessary for comparison in order to understand on a fundamental level long-term adaptation to war trauma and the influence of various factors on this adaptation. In this comparison it is of paramount importance to integrate data from non-Western societies.

Our study in Mozambique is one of few carried out in the non-Western home country of survivors of trauma and in a community setting. Friedman & Jaranson (1994) discuss the results of some prevalence studies carried out in refugee camps, most of which were in South-East Asia. Their conclusion is that the PTSD concept is useful in non-Western societies and that it gives a context for a therapeutic approach. Many studies of non-Western populations, however, were carried out in Western countries among refugees and asylum seekers. Although these studies generate important information on cross-cultural phenomena in post-traumatic stress symptomatology, influences pertaining to being an asylum seeker or refugee in a foreign country are also involved.

An important question in this kind of cross-cultural research is whether diagnostic procedures and instruments of Western origin are applicable in a non-Western population. Kleijn et al (1998), in a study of 169 traumatised refugees and asylum seekers, showed that it is possible to use standardised psychological and psychiatric instruments to measure the prevalence of symptoms of anxiety, depression and PTSD in patients from non-Western countries. The population was very diverse in language, culture and education. In this study the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) (Reference Mollica, Caspi-Yavin and BolliniMollica et al, 1992) and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL–25) (Reference Mollica, Wyshak and De MarneffeMollica et al, 1996) gave an adequate indication of symptomatology. The level of post-traumatic symptoms, including the prevalence of nightmares, was particularly high. In our Mozambique study, quantitative means of assessment were used in combination with qualitative methods, such as interview and observation. Comparison between these two methods helps to avoid blind spots and is strongly recommended.

Diagnosis and treatment

As mentioned above, in diagnosing post-traumatic stress symptoms in patients from Western and non-Western societies, questionnaires such as the HTQ and HSCL–25 can be used in addition to a clinical interview. Once the diagnosis of (partial) PTSD has been made, the patient (and partner) needs information about the symptoms of PTSD and about possible treatments. Symptoms of hyperarousal and re-experiencing, including nightmares, might have negative effects on a relationship, so a partner should at least be invited to attend when information is given. Often the partner will also be involved in the treatment process.

As Shalev et al (1993) indicated, the treatment of partial or complete PTSD often uses multiple methods: which combination of treatments is used depends on several factors (Box 4).

Box 4. Treatments for post-traumatic nightmares (PTNMs)

Support

Inform the patient and partner (if there is one) about the symptoms

Psychotherapy

Symbolic PTNMs: all psychotherapies, including psychoanalytic psychotherapy

Replicative PTNMs: behaviour therapy (counter-conditioning)

Pharmacotherapy

Symbolic PTNMs: not indicated

Replicative PTNMs: antidepressants (first choice: tricyclics; second choice: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors); cyproheptadine; and nefazodone (promising but not proved)

Psychotherapy

In the case of traumatised war victims, in deciding whether psychotherapy is indicated, one has to take into account the circumstances in which individuals are living. Asylum seekers, for example, may live in a very insecure situation, awaiting the decision on their right of asylum. Sequential traumatisation may be induced by these feelings of not being safe, by adjustment problems, bad housing, aggression, discrimination and so on. In such circumstances, only supportive therapy is usually indicated. Addressing the traumatic experiences directly might destabilise the patient even more. However, in a more stable situation, supportive psychotherapy using cognitive–behavioural techniques has proven to be the best treatment for traumatised patients from non-Western countries (Reference Basoglu and BasogluBaşoǧlu, 1992). This might be done in combination with non-verbal therapy and support with daily problems such as housing, language and adjustment.

Particular attention should be paid to the attributions patients make to their symptoms. In the case of a patient who attributes bad dreams to angry ancestors, a quite different therapeutic intervention is required than in the case of a person who thinks that nightmares are simply frightening and annoying and wants to get rid of them.

In a later phase of therapy, when intense re-experiencing and nightmares have subsided, testimony therapy might be indicated; this aims at integrating traumatic experiences into the individual's life history (Reference Cienfuegos and MonelliCienfuegos & Monelli, 1983; Reference van Dijk and Schreudervan Dijk & Schreuder, 2001).

Intrusive phenomena such as PTNMs might be a guideline in the choice of treatment. Often, symbolic PTNMs are not too disturbing and their frequency might increase during cognitive–behavioural or psychodynamic psychotherapy. Replicative PTNMs, however, especially if they are accompanied by symptoms of hyperarousal, inhibit the elaboration of traumatic experiences. These, therefore, should be treated with behavioural therapy (relaxation and counter-conditioning) and/or pharmacotherapy.

Drug treatments

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), tricyclic antidepressants, lithium carbonate and clonidine suppress PTNMs, as they reduce the amount of REM sleep (Reference Ross, Ball and SullivanRoss et al, 1989). Most common pharmacotherapy for PTSD are a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or a tricyclic antidepressant (Reference Davidson, Van der Kolk, van der Kolk, McFarlane and WeisaethDavidson & van der Kolk, 1996). The authors experience is that the effect of both on PTNMs differs among patients, from a good effect to an adverse effect. The differing therapeutic effect of individual drugs might be explained by the different pharmacological processes in symbolic and in replicative PTNMs. Lithium carbonate, by decreasing REM sleep, increasing the synchronisation of brainwaves and lessening cortical arousal, may have a favourable effect on replicative PTNMs. However, this has not been empirically tested.

Several clinical reports suggest that cyproheptadine might be promising in the treatment of PTNMs, although this remains controversial (Reference Jacobs-Rebhun, Schnurr and FriedmanJacobs-Rebhun et al, 2000; Reference Rijnders, Laman and van DuijnRijnders et al, 2000). It acts as a histamine–1 (H1) and serotonin–2 (5–HT2) receptor antagonist. Another drug that might be of interest is the recently approved antidepressant nefazodone (Reference MellmanMellman, 1997). This is primarily serotonergic and decreases replicative PTNMs. Further research on the pharmacotherapy of intrusive post-traumatic symptoms is needed.

Multiple choice questions

-

1. The following are found in both Western and non-Western societies after war trauma:

-

a sleep disorders

-

b panic attacks

-

c obsessive–compulsive symptoms

-

d depressive symptoms.

-

-

2. Universal intrusive phenomena after traumatic experiences include:

-

a flashbacks

-

b hypnagogic hallucinations

-

c nightmares

-

d night terrors.

-

-

3. Current treatment strategy for PTSD depends on:

-

a cultural influences on the symptomatology

-

b blood levels of cortisol

-

c the social situation of the patient

-

d if the patient has a partner.

-

-

4. The following are indispensable in treating a traumatised refugee with a diagnosis of PTSD:

-

a behavioural therapy

-

b family therapy

-

c psychoeducation

-

d supportive therapy.

-

-

5. Pharmacotherapy of PTSD might be indicated if the following symptoms predominate:

-

a replicative nightmares

-

b hyperarousal

-

c symbolic nightmares

-

d avoidance symptoms.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | T | a | T | a | T | a | F | a | T |

| b | T | b | F | b | F | b | F | b | T |

| c | F | c | T | c | T | c | T | c | F |

| d | T | d | F | d | T | d | F | d | F |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.