1 Introduction

A learning organisation can be defined as ‘an organization skilled at creating, acquiring, and transferring knowledge, and at modifying its behaviour to reflect new knowledge and insights’.Reference Garwin1 The concept of a learning organisation began to develop during the 1980s and 1990s, as the evidence-based medicine movement aligned with the advent of electronic health data to make large-scale learning both desirable and feasible. It took a leap forward in 2001, when the US Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) landmark report Crossing the Quality Chasm identified the potential for information technology to underpin improvement.2 A 2006 IOM roundtable on evidence-based medicine then introduced the idea of a ‘learning healthcare system’.3 Over almost two decades, the concept has evolved and spread, and is now used to describe a wide range of structures and activities.4

In this Element, we briefly outline what is meant by a learning health system. We emphasise that while digitisation of healthcare has been crucial to the development of learning health systems, social and cultural factors are critical too.Reference Foley and Zahran5 We present a sociotechnical framework, recognising the interaction between people and technology. The framework helps structure thinking about the design and operation of learning health systems. We explore the role of complexity and the components that make up a learning health system. Finally, we offer a critique of the learning health system approach, recognising that more has been said about the aspiration than perhaps has been delivered.

1.1 Learning Health Systems as Sociotechnical Systems

There have been many definitions of a learning health system, but a particularly useful one emerged from the IOM, describing a health system in which:

science, informatics, incentives, and culture are aligned for continuous improvement and innovation, with best practices seamlessly embedded in the delivery process, patients and families’ active participants in all elements, and new knowledge captured as an integral by-product of the delivery experience.Reference McGinnis, Stuckhardt, Saunders and Smith6

This definition makes it clear that a learning health system is not a data or a technology project, but the evolution of a healthcare system into one that learns from every patient who is treated and is able to apply that learning in real time to shape practice. Learning health systems come in many different shapes and sizes. There is no single typical example. Some learning health systems involve multiple organisations that collectively meet the IOM criteria for a single disease or treatment modality (e.g. ImproveCareNow for paediatric bowel disease); others are limited to a single healthcare entity but encompass all its care (e.g. Geisinger Health System, Pennsylvania, USA; NYU Langone Health, New York, USA). There are even some efforts to create learning health systems at a national level (e.g. the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Sentinel programme which monitors the safety of medical products). Learning health systems may try to address diverse goals, including:

improving patient outcomes and experience

providing better value healthcare

reducing unwarranted variation

generating and applying generalisable knowledge

monitoring evolving trends and epidemiological phenomena

improving education, training, and performance of the workforce.Reference Foley and Zahran5

Learning health systems can focus on operational improvement, research, or clinical issues. What unites them is the common cycle of capturing data from practice, turning it into knowledge, and putting knowledge back into practice.

A learning health system is not a distinct healthcare improvement method. Rather, a learning health system requires development of systematic organisational capabilities that can enable the routine deployment of multiple improvement methods, including many of those outlined in other Elements in this series. Also fundamental is that a learning health system is an ongoing journey rather than a destination (see Box 1).Reference Zurynski, Smith and Vedovi7

Box 1 Geisinger Health System

Geisinger Health System (GHS) is an integrated health services organisation on a learning health system journey. Its aim is to continuously generate knowledge, improve care, and deliver value.Reference Psek, Stametz and Bailey-Davis8

GHS serves more than 2.6 million residents throughout central and northeast Pennsylvania in the USA. It uses advanced patient- and clinician-facing technologies that generate high-quality data assets, with the GHS enterprise warehouse aggregating clinical, financial, and social determinants data from over 100 sources.Reference Davis, Williams and Stametz9

As well as data and technology, GHS makes use of patient-populated advisory groups, focus groups, surveys, and other methods to involve patients in policy development, quality improvement, and clinical innovation.Reference Davis, Williams and Stametz9

GHS uses data, knowledge, and systems engineering to drive a continuous care improvement cycle in the following ways:Reference Foley and Fairmichael10

process automation to reduce clinical workload – for example, by prepopulating clinic notes with existing data

clinical decision support – for example, prepopulating order sets mapped to best practice guidelines

predictive modelling to identify potentially high-risk or high-cost situations such as clinic ‘did not attends’

collaboration and data sharing with regional neighbours to improve the quality and convenience of care

national and international collaborations on research and learning health system components

consultancy support for other organisations.

GHS is increasingly recording patient reported outcomes and patient experience data from inside and outside the clinic. It has created a behavioural insights team that addresses behaviour change challenges across the clinical departments and measures the effectiveness of interventions using rapid A/B testing (a rapid randomised experiment involving two variants).Reference Davis, Williams and Stametz9

Patients are encouraged to become active partners with clinicians in their own care through an online portal. They are encouraged to contribute to research, improvement, and innovation through patient and family advisory councils. Patients are also involved in the design process through use of the five-step Stanford design thinking model: empathise, define, ideate, prototype, and test.Reference Davis, Williams and Stametz9

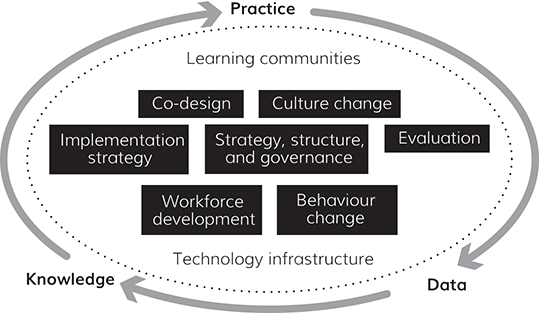

At its core, a learning health system is one in which is there is a constant cycle of practice to data to knowledge and then back to practice (Section 2). Such systems are extremely complex (Section 3). Supporting the learning cycle, at whatever level (team, small provider, regional group of organisations, national or even international system), requires the foundations of a learning community and technological infrastructure. Alongside these are several other components, which we refer to in this Element as the foundations and building blocks of a learning health system (Section 4).Reference Psek, Stametz and Bailey-Davis8, 11–Reference Greenhalgh, Wherton and Papoutsi16 Despite the diversity of learning health systems, this framework (shown in Figure 2) seeks to address issues that are common to all the examples which meet the definition given at the beginning of this section.

2 The Data-Knowledge-Practice Learning Cycle

At the core of the learning health system is the learning cycle: collecting data from routine practice, analysing that data to generate new knowledge, and translating that knowledge back into improved practice (Figure 1).Reference Flynn, Friedman, Boisvert, Landis-Lewis and Lagoze17

Figure 1 The data-knowledge-practice learning cycle

2.1 Practice to Data

A learning health system needs to be able to collect and assemble relevant data from practice to support its activities. One key source of data for many learning health systems is the electronic health record, which can generate both highly structured data that can be used for quantitative analysis and free text that can be mined using techniques such as natural language processing or tools such as large language models.Reference Foley and Fairmichael18, Reference Fink, Bischoff and Fink19, Reference Hsueh, Nethala and Singh20

Using data collected during routine care for learning system purposes is not straightforward. Because the data is generated as a by-product of care provision, it is not always high quality. If collected data is inaccurate, incomplete, or out of date, then the knowledge generated may have the same problems, which could result in poor decisions and possibly harm to patients.Reference Obermeyer, Powers, Vogeli and Mullainathan21 Improving data quality requires a multi-level, sociotechnical effort from patients and staff, clinical coders, system designers, and analysts, ideally supported by some higher-level oversight. For example, in the NHS, the automated Data Quality Maturity Index (DQMI)22 is used to assess the quality of data submitted by providers. DQMI results are published and fed back to data providers to drive improvements. However, the DQMI cannot detect some important aspects of data quality, such as inaccurate data flowing from a provider. Catching such errors currently depends on analyst’s contextual knowledge of the dataset, the providers, historical data, and the clinical environment where the data are generated.

Large-scale collection of data across one or more organisations requires standards for their definition and exchange to be interoperable.23 Standards for the terminologies and classifications24, 25, 26 used to describe healthcare, and how data are structured,27, 28 transported,29, 30 and secured,31 have been slow to develop, but are now gaining more widespread adoption. For example, the Systematized Nomenclature Of Medicine Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT) contains an enormous number of standardised clinical terms, including procedures, symptoms, measurements, diagnoses, and medications.24 This allows data in different electronic health record systems to be stored accurately and consistently.

The level of data quality required will depend on what use the data will be put to in each case. Sometimes, depending on the goals of a particular effort, quality challenges may be impossible to overcome, and data may need to be gathered prospectively for a specific purpose rather than being generated from routine care records.

Data must also be protected from inappropriate access and use. Information governance is how organisations ensure that individuals can trust them to use their data fairly, responsibly, and ethically. In the UK, information governance is underpinned by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which is implemented in law by the Data Protection Act 2018.32, 33 In the United States, data use and sharing are governed largely by the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act of 1996.34 But whatever the legislation, a learning health system must co-design an information governance framework to the satisfaction of its patients and learning community as well as addressing legal and ethical requirements.

2.2 Data to Knowledge

Once data are available in a standardised, comprehensive, exchangeable, and analysable form, the next challenge is to derive knowledge from the data. Numerous designs and analytic methods can be used, with a selection outlined in Table 1.

Table 1 Special considerations in design and analytical methods for learning health systems

| Method | Special considerations for learning health systems |

|---|---|

| Experimental designs that can be used to generate reproducible knowledge | |

| RandomisationReference Horwitz, Kuznetsova and Jones35 | Systems-level or operational activities can be randomised, just like clinical therapeutics. Randomised tests can rapidly generate evidence about the value of different ways of organising workflows, processes, and communications. |

| Pseudo-randomisationReference Ellenberg36 | Embedding pure randomisation into routine care is not always practical. But alternatives – such as alternating approaches between week on and week off, or between odd and even medical record numbers – are often close to random and more feasible. |

| Quasi-experimental analyses that can be used to generate reproducible knowledge | |

| Difference-in-differences analysis | This is particularly useful for studying unit-, hospital- or population-level event rates, for which there are often naturally existing control groups. |

| Interrupted time series (ITS)Reference Penfold and Zhang37 | An advantage of ITS over difference-in-differences design is its ability to account for pre-intervention trends. ITS can also be done without a control group,Reference Devkaran and O’Farrell38 so it’s useful in situations where there is no naturally existing comparison (e.g. to generate data from an entire hospital or ambulatory practice). |

| Regression discontinuityReference Maciejewski and Basu39, Reference Desai and McWilliams40 | This method is useful when there is a specific threshold at which an intervention is applied (e.g. a target laboratory result, a qualifying income, a population percentage). |

| Artificial control groupsReference Rosenbaum41, Reference Iacus, King and Porro42 | These methods allow analysis of patient-level data where there is concern about selection bias – for example, generating knowledge from care coordination programmes in which entrance into the programme is likely confounded by self-efficacy and interest. |

| Statistical process controlReference Neuburger, Walker, Sherlaw-Johnson, van der Meulen and Cromwell43 | This is a useful technique from manufacturing that can help identify whether outcomes are stable over time or varying in a random or non-random fashion. See the Element on statistical process control.Reference Mohammed, Dixon-Woods, Brown and Marjanovic44 |

| Non-experimental analyses that can be used to generate reproducible knowledge | |

| Artificial intelligence (AI) | AI methods can help to discover undiagnosed disease,Reference Bejnordi, Veta and Diest45 identify new subtypes of disease,Reference Seymour, Kennedy and Wang46 predict future events,Reference Pavlou, Ambler and Guttmann47, Reference Miotto, Li, Kidd and Dudley48 optimise treatment selection,Reference Liang, Fan, Luo and Zhu49 and manage complex medications.Reference Woldaregay, Arsand and Walderhaug50 |

| Learning from local experience | Descriptive statistics alone can generate useful insight. For example, Stanford University developed a service that rapidly interrogates the electronic health records of similar patients when a question arises about a patient’s optimal treatment or ultimate prognosis.Reference Longhurst, Harrington and Shah51 The service then delivers a descriptive summary of what happened to the other patients. |

| Data visualisation | Creating simple visual or qualitative representations of data can often generate important insights. See the Elements on lean and associated techniques for process improvement,Reference Radnor, Williams, Dixon-Woods, Brown and Marjanovic52 and measurement for improvement.Reference Toulany, Shojania, Dixon-Woods, Brown and Marjanovic53 |

| Collaborative learning | Knowledge generation in a learning health system cannot always be automated. Humans are uniquely well suited to understanding the complexity of such systems. Deliberative approaches involving all members of the learning community can generate rich knowledge for improvement.Reference Martin, Dixon-Woods, Dixon-Woods, Brown and Marjanovic54 |

Regardless of the method applied, converting data to knowledge requires more than access to the data and the technical ability to design processes with evaluation in mind. To consistently generate knowledge from the data, those technical skills need to be supported by the foundations and building blocks shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Learning health system framework

One example of how this has been achieved is the NYU Langone Health system in New York, USA. Using a learning system approach, it established a rapid randomised quality improvement project unit and randomised over a dozen interventions in its first year. The health system was able rapidly to determine the effectiveness of a variety of interventions, including community health worker facilitation, post-discharge telephone calls, letters, and electronic clinical decision support.Reference Horwitz, Kuznetsova and Jones35, Reference Horwitz and Krelle55, Reference Austrian, Mendoza and Szerencsy56 However, the programme succeeded not simply because NYU Langone Health had statisticians who could randomise interventions, but because:

The improvement unit was embedded in a system whose leadership deeply valued achieving best outcomes and cared about proving the value of activities performed by staff.

Frontline clinical staff had a culture of flexibility, adaptability, and – crucially – trust, such that they were willing to experiment with different approaches confident that they wouldn’t lose their positions if an activity they performed was shown not to be effective.

The IT system was strategically designed to support evaluation and improvement, not just to allow for billing.

The interventions tested were co-designed with frontline staff who understood the complexity of the system in which they were working.

Both intervention and evaluation were designed to account for unintended consequences and downstream effects.

2.3 Knowledge to Practice

A system that purely generates knowledge is not a learning health system. A learning health system must complete the cycle by translating the knowledge gained from the system back into practice to continuously improve health and care. Importantly, learning health systems generate knowledge about operations and management, not only about clinical care. These learnings, too, must be translated into practice.

Knowledge can influence practice through publication in journal articles, books, or guidelines; it can be passed on through formal and informal education, training, or other interactions; and it can be used to redesign care environments and health interventions.

Decision-makers often have preferences based on local knowledge, relationships, power structures, or the experience of neighbours.Reference Swan, Clarke and Nicolini57 And some aspects of clinical practice, such as general problem-solving, procedural skills, healthy attitudes, and professional behaviours are unlikely to be readily replaced by computable knowledge. Tacit knowledge can be communicated through dialogue. Direct interaction and relationships, as well as cross-boundary dialogue, are critical as drivers of learning.Reference Milligan and Berta58 This can be fostered through a learning community approach, in alignment with the foundations and building blocks of learning health systems (see Section 4).

These approaches are often slow. In a learning health system, the process of applying knowledge to practice can sometimes be sped up. First, learning health systems can be designed to rapidly generalise learning. At NYU Langone Health, for example, an iterative, rapid, randomised set of projects ultimately resulted in an optimal script for engaging patients in preventive care such as cancer screening and diabetes-related screening. The key elements of the script (brevity, starting immediately with the ‘ask’, including direct links to online appointment scheduling where available, tailoring contact times to those most suited for patient workflow, incorporating reminders) were immediately generalised to other patient outreach scenarios beyond the ones initially tested because the project involved the frontline staff responsible for all outreach and was designed from the start to be relevant to other situations.

Second, clinical decision support systems can be effectively leveraged for rapid deployment of knowledge across a learning health system by bringing knowledge and guidance to the point of care at the specific moment it is needed (see the Geisinger example (Box 1)).

Traditional decision support requires an underlying logical algorithm (e.g. for a patient meeting a, b, and c characteristics but not d, e, or f, suggest x, y, z interventions) that is manually built based on evidence-based rules and is therefore resource-intensive, slow to implement, and vulnerable to becoming obsolete when new knowledge is generated. One way implementation and update of decision support could be sped up would be to represent new knowledge not just as human-readable guidelines, but as machine-readable code, and then to make such code centrally and openly available to any learning health system. Decision support systems could be designed to reach externally for those rules rather than relying on local code, enabling prompt updates and widespread adoption of knowledge into practice. At present, such programmes are more ambition than reality, though several early efforts exist.59–62

Any decision support system, whether local or centrally built, has limitations. Patients may not fit the guideline criteria if they have multiple conditions or are taking conflicting medications. The decision support system might not incorporate unstated common-sense rules (e.g. suggesting a pregnancy test in male patients).Reference Walsh and Wroe63, Reference Wong and Peek64 Perhaps unsurprisingly, machine-readable knowledge that is intended to be applied at the point of care therefore has the potential to cause harm. In England, compliance with clinical safety standards DCB0129 (for manufacturers) and DCB016065 (for deploying organisations) is mandatory under the Health and Social Care Act 2012.66 Under the Medical Devices Regulation published by the European Commission in 2017, software such as a clinical decision support system would be considered a medical device and need to be registered with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency in the UK and audited by a notified body.67

3 Understanding and Managing Complexity in Learning Health Systems

The promise of learning health systems has been that they will revolutionise healthcare by capturing and analysing clinical data to continuously inform and improve decision-making and practice, as described in the previous section.Reference Bernstein, Friedman, Jacobson and Rubin68, Reference Friedman, Rubin and Brown69 But this is to take too simplistic or optimistic a view of what is ultimately a complex intervention in a complex health system. Such complexity helps to explain why, nearly two decades after the IOM first popularised the concept of a learning health system, no nation, region, or single healthcare provider has fully realised that promise.Reference Foley and Zahran5 Indeed, uncontrolled complexity has been cited as the reason for the failure of many health IT programmes and learning health systems to scale successfully.Reference Greenhalgh, Wherton and Papoutsi16, Reference Nonadoption70

Healthcare is a complex adaptive system.Reference Braithwaite71 It has a vast number of interacting elements with non-linear interactions (meaning that small changes can have disproportionate and often unanticipated consequences), the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, and the system evolves in unpredictable ways.Reference Snowden and Boone72 This complexity is exemplified by the NHS in England, with over one million staff and hundreds of provider organisations grouped into regional structures, all overseen by an ever-changing central administrative structure that is influenced by politicians, the media, and professional bodies. It is the largest part of a broader ecosystem of organisations that together represent one tenth of the country’s economic output. The learning health system examples outlined in this Element are themselves complex interventions.

In this section, we will explore complexity by applying Greenhalgh et al.’s non-adoption, abandonment, scale-up, spread, and sustainability (NASSS) framework for health and care technologies to learning health systems (Section 3.1) and looking at Greenhalgh et al.’s principles for how to manage complexity in a learning health system (Section 3.2).

3.1 Understanding Complexity

Greenhalgh et al.’s NASSS framework for health and care technologiesReference Greenhalgh, Wherton and Papoutsi16 (see the Element on approaches to spread, scale-up, and sustainabilityReference Papoutsi, Greenhalgh, Marjanovic, Dixon-Woods, Brown and Marjanovic73) has been operationalised with a series of complexity assessment tools (CATs) called NASSS-CAT.Reference Greenhalgh, Maylor and Shaw74 NASSS guides an understanding of complexity across seven domains, outlined in Box 2.Reference Greenhalgh, Wherton and Papoutsi16

Box 2 Domains of complexity within the NASSS frameworkReference Greenhalgh, Wherton and Papoutsi16

The condition or illness: According to NASSS, the clinical scenario with which a learning health system is concerned is critical to its likelihood of success. Earlier studies have found that potential patients were often deemed unsuitable for a given intervention because of the complexity of their condition, comorbidities, or sociocultural situation.Reference Greenhalgh, Wherton and Papoutsi16

The technology: Problems with usability and dependability have often been cited as reasons for the failure of technology interventions.Reference Carayon and Hoonakker75 Another danger is that data produced by technologies may be misinterpreted by patients or clinicians, particularly if the data do not measure the underlying illness directly. Skills and training may also be needed to enable scale-up and spread. Systems that are ‘plug and play’ or ‘off the shelf’ can more easily be replaced by other equivalent systems and so avoid the risk of lock-in or provider failure.

The value proposition: Is a learning health system worth developing, and for whom will it generate value? If there is no clear business case, then the innovating organisation will be unable to scale and spread. And if there is no value to the organisation (e.g. a hospital or General Practice), then it will be equally likely to fail. Value can include benefit to patients or improved efficiency, and it can rely on reimbursement and payment mechanisms.

The adopter system: The staff, patients, and carers (the ‘adopters’) who have to adopt the system (and continue using it) are critical to its success. Staff sometimes abandon technology because of usability problems, but more often they do so because of threats to their scope of practice, fear of job losses, or concerns about patients’ safety or welfare.Reference Greenhalgh, Wherton and Papoutsi16 Patients may be unable to realise the benefits because of the amount of work or capability required of them.Reference Greenhalgh, Wherton and Papoutsi16 The same is likely to be true of learning health systems. Weak social networks or a lack of skills among carers can result in reduced access.Reference Waights76

The organisation: The organisation’s capacity and readiness for change will influence the development and scale-up of a learning health system internally.Reference Nonadoption70 This process can be made easier where there is organisational slack, but a learning health system that requires significant disruption to existing routines can create resistance. The decision on whether to fund and support a learning health system will be influenced by business modelling, yet it is often impossible to predict costs and benefits in advance. The work involved in implementation is commonly extensive and underestimated at the planning stage. In some cases, innovation can be achieved by working with another more innovative organisation.

The wider context: The wider institutional, policy, and sociotechnical context has often been identified as a key factor in organisations’ failure to move from demonstration project to a fully mainstreamed service (scale-up) that is widely transferable (spread) and sustainable (i.e. persists over time).Reference Greenhalgh, Wherton and Papoutsi16 This context can include policy, political, information governance, interoperability, legal, market, intellectual property, and regulatory considerations.

Adapting over time: All the other domains will change over time, so to be successful a learning health system must be able to adapt to such change. Likewise, the organisation must have the resilience to respond to critical events.

3.2 Managing a Learning Health System as a Complex System

Greenhalgh et al. have adapted existing principles for managing complexity so that they are relevant to the development of a learning health system. They suggest the following:Reference Greenhalgh, Maylor and Shaw74

Acknowledge unpredictability – designers of interventions should contemplate multiple plausible futures; implementation teams should tailor designs to local context and view surprises as opportunities.

Recognise self-organisation – designers should expect their designs to be modified, perhaps extensively, as they are taken up in different settings; implementation teams should actively capture data and feed the data into the adaptation process.

Facilitate interdependencies – designers should develop methods to assess the nature and strength of interdependencies; implementation teams should attend to these relationships, reinforcing existing ones where appropriate and facilitating new ones.

Encourage sense-making – designers should build focused experimentation into their designs; implementation teams should encourage participants to ask questions, admit ignorance, explore paradoxes, exchange different viewpoints, and reflect collectively.

Develop adaptive capability in staff – individuals should be trained not merely to complete tasks as directed but to tinker with technologies and processes and make judgements when faced with incomplete or ambiguous data.

Attend to human relationships – embedding innovation requires people to work together to solve emergent problems using give and take and muddling through.

Harness conflict productively – there is rarely a single right way of tackling a complex problem, so conflicting perspectives should be viewed as the raw ingredients for multifaceted solutions.

These principles inform the components that need to be considered when developing a learning health system. These are discussed in the following section.

4 Components of Learning Health Systems

To enable the practice-data-knowledge-practice improvement cycle (Section 2) within the complex environment described in Section 3, it is helpful to have a set of building blocks in place. These building blocks align with the foundations of learning health systems, which are learning communities and technology infrastructure. These two foundations and the building blocks are illustrated in Figure 2 and explained in the subsections that follow. The section concludes with an overview of a maturity assessment tool, used to understand the degree to which the components of a learning health system are achieving a specific objective.

4.1 Learning Communities

A learning community,Reference Wilson and Lowe77, Reference Ferguson, Dibble, Williams and Ferraro78 whose role is to determine what to improve and to direct activity, is foundational to the learning health system. The learning community guides each of the three key stages of learning described in Section 2.

A large system might have multiple learning communities, perhaps involving collaborations with researchers and funders79 or organised into specialised institutes.Reference Davis, Williams and Stametz9 Learning communities have also been successfully developed for specific diseases, such as ImproveCareNow for paediatric inflammatory bowel disease.Reference Seid, Dellal and Peterson80, Reference Hartley, Keck, Havens, Margolis and Seid81 Crucially, learning communities should involve patients, not just staff. This is because healthcare is not produced solely by healthcare organisations but co-produced by patients interacting with the healthcare system. Therefore, collaborative learning must involve co-planning, co-design, co-delivery, and co-assessment with patients.Reference Batalden, Batalden and Margolis82

Detailed resources are available to guide the development of a learning community,Reference Wilson and Lowe77 but in brief, it typically comprises a group of stakeholders who reflect on experience, share judgements, consider uncertainties, and make sense of evidence with the purpose of collective improvement.Reference Wilson and Lowe77 As well as generating knowledge, a learning community can also build trust, capacity, skills, confidence, and agency for change. It should both challenge its members and provide reassurance.Reference Wilson and Lowe77

The learning community has an important role at each stage of the learning cycle: practice to data, data to knowledge, and knowledge to practice.

4.2 Technology Infrastructure

A learning health system will require access to technology infrastructure, perhaps in the form of its electronic health record system or a data warehouse, to support its activities. Technological infrastructure can support every stage of the learning cycle (practice to data, data to knowledge, and knowledge to practice). Recent years have seen the emergence of platforms offering ready-made solutions for data management, governance, user interfaces, application programming interfaces, decision support, and workforce solutions. This has made it increasingly affordable for even small organisations to build learning health systems without the need to reinvent each part locally.

Other technological platforms found in a learning health system might include patient portals, decision support systems, regional health information exchanges, business intelligence, and analytics systems.

Platform providers include large IT companies (such as cloud providers), start-ups, electronic record system vendors, academic groups, and even healthcare providers. NHS England has developed a national Federated Data Platform that can harness data across multiple providers, enabling more effective transitions of care and operational coordination.83 In addition, a Secure Data Environment structure for research access allows researchers to access data within the environment while maintaining safety and security.84

In the United States, the Mayo Clinic Platform links deidentified data from eight health systems in six countries in a federated manner to support health and health system research as well as to provide data for better health system decision making.85 Similarly, the electronic health record vendor Epic has aggregated data from across its clients to create a deidentified dataset with data from 259 million patients receiving care at more than 35,400 clinics and more than 1,500 hospitals that is available to member institutions for analytics and research.86, Reference Tarabichi, Frees and Honeywell87

4.3 Building Blocks

As shown in Figure 2, several building blocks need to be considered within a learning health system. These are each discussed next.

4.3.1 Strategy, Structure, and Governance

Strategy generally involves setting goals and priorities, determining actions to achieve those goals, and mobilising resources to execute the actions.Reference Freedman88 Ultimately, strategy is a set of interrelated choices about how a team or organisation(s) will deliver value.Reference Lafley and Martin89

To be successful, a learning health system requires strategic thinking and must be part of the wider organisation’s strategy. And like every other element of a learning health system, strategy must be co-designed by the stakeholders. Many guides and tools are available to help organisations with this.Reference Freedman88–Reference Rumelt91 Geisinger’s learning health system (see Box 1) strategy is, for example, aligned with its organisational strategy.Reference Davis, Williams and Stametz9 However, Geisinger does not claim to have fully realised its goal of becoming a learning health system, seeing it as ‘a moving target’.Reference Davis, Williams and Stametz9 It recognises a continuing need for better alignment of its mid-high-level leadership with the learning health system concept, including cultural change and strategic alignment in different departments. In common with most organisations, entrenched cultures have been difficult to change. These are expected to be long-term challenges.Reference Davis, Williams and Stametz9

Once a strategy has been developed, people and resources must be organised to deliver it effectively – a process sometimes known or represented as a target operating model (TOM) or an organisational architecture.92, 93 Britto et al. propose an ‘actor-oriented learning network organisational form’ with three components:Reference Britto, Fuller and Kaplan94

aligning participants around a common goal

standards, processes, policies, and infrastructure to enable multi-actor collaboration

a ‘commons’ (a shared repository) where information, knowledge, resources, and know-how to achieve the goal are created and shared.

4.3.2 Culture Change

A learning health system requires a culture of learning, innovation, sharing, implementation, and research.Reference Scobie and Castle-Clarke95 Three interrelated layers of group or organisational culture can be identified:Reference Mannion and Davies96

Visible manifestations of a healthcare culture include the distribution of services and roles (e.g. the divide between primary and secondary care, or between health and social care), the physical layout of facilities, pathways of care, workforce practices, reporting arrangements, dress codes, incentive systems, and established quality improvement and clinical governance models.

Shared ways of thinking include the values and beliefs that justify the visible manifestations and the rationales given for doing things differently, such as prevailing views on autonomy, dignity, evidence, and service improvement.

Deeper shared assumptions are the often-unconscious underpinnings of day-to-day practice, such as assumptions about the roles of patients, carers, and different professionals.

These layers are learned, shaped, and reinforced through training and experience. Culture can be conceptualised as a force that structures and shapes interactions and therefore forms part of the infrastructure of a learning health system.Reference Vinson97 Any given system may include subgroups (e.g. clinicians and managers) with different cultures. The multidisciplinary (often multiagency) nature of a learning health system increases the risk of culture clashes.

Assessing and changing culture are crucial to a learning health system succeeding.Reference McGinnis, Stuckhardt, Saunders and Smith6 Many tools are available to guide that process,98, Reference Dave Snowden99 but no one tool is right for every situation.Reference Jung, Scott and Davies100 Changing a culture is one of the most difficult, but crucial, challenges. See the Element on making culture change happen for further discussion.Reference Mannion, Dixon-Woods, Brown and Marjanovic101

4.3.3 Workforce Development

A learning health system will contain the broad range of patients and clinical and non-clinical disciplines that would be expected in any health system. It may also include designers, researchers, analysts, data scientists, and knowledge management staff, among others.Reference McGinnis, Stuckhardt, Saunders and Smith6 The workforce may also be distributed across multiple organisations, creating leadership challenges in developing a learning culture and delivering a coherent strategy.Reference Wachter, Adler-Milstein and Brailer102

As the boxed examples in this Element show, the workforce involved in a learning health system will continue to need the mix of skills required by traditional healthcare organisations. These include leadership, communication, and teamworking skills, service improvement and clinical effectiveness skills, and equality and diversity awareness.Reference Foley and Woollard103 The workforce may also require new skills around data capture,Reference Foley and Fairmichael104 data interpretation,Reference Foley and Fairmichael18, Reference Foley and Fairmichael105, Reference Foley106 research,Reference Foley and Fairmichael18 and managing continual change.Reference Foley and Fairmichael105 These requirements are represented in recent UK competency frameworks,107 and their systematic development within the workforce will require long-term planning.Reference Foley and Zahran5

4.3.4 Co-design

Stakeholders should be involved in the development of every element of a learning health system. They are critical to understanding the true complexity of what, superficially, may look like a technical undertaking. Design is a creative process to solve complex problems,86 and user-centred design brings stakeholders into the process. ISO 9241-210 is the international standard in human-centred design for interactive systems.108 NHS England has created a set of NHS design principles based on this standard.109 Those principles can usefully be applied when developing each element of a learning health system.

The process of meaningfully involving stakeholders has been called many things – co-design, co-production, co-creation, patient-centred, patient engagement, and more. Each of these terms has important definitional differences, but the central objective is to create learning health system interventions that work in the real world.Reference Reponen110, Reference Sanders and Eva Brandt111 Many guides to co-design112, 113 are available, along with several online, open-source databases of design tools114, 115, 116 that can be applied to learning health system development. However, evidence on how to select the most appropriate tools is limited,Reference Vandekerckhove, de Mul, Bramer and de Bont117 so that decision will fall to the learning community and will be influenced by the task, the stakeholders, and the outputs required.

Multiple tools may be used to provide different perspectives on the complex system.Reference Foley and Zahran5 It is important to recognise that a learning health system is a service, rather than a product to be manufactured. Therefore, to a greater or lesser extent, it is naturally co-produced by the patient and the clinician through their interactions.Reference Batalden, Batalden and Margolis82 For further discussion of these issues, see the Element on co-producing and co-designing.Reference Robert, Locock, Williams, Dixon-Woods, Brown and Marjanovic118

4.3.5 Implementation Strategy

Learning health systems are often large, complex organisations with multiple interventions, so their development is likely to benefit from an implementation strategy. This is an integrated package of discrete approaches, ideally selected to address specific identified barriers to implementation success.Reference Bauer, Damschroder, Hagedorn, Smith and Kilbourne119 Approaches might cover behaviour change, training, feedback, incentives, learning communities, and stakeholder engagement. The implementation strategy should focus on the successful integration and use of the range of learning health system interventions. See the Element on implementation science for further detail.Reference Wilson, Kislov, Dixon-Woods, Brown and Marjanovic120

4.3.6 Behaviour Change

In many cases, a learning health system requires patients, clinicians, and others to change their behaviour to realise an improvement in practice. Many theories and models can be deployed to understand and aid this process.

The behaviour change wheel is one example of a systematic approach to designing, implementing, and evaluating behaviour change interventions in any setting.Reference Michie, van Stralen and West121 It is based on a collection of existing theoretical frameworks and has been applied to learning health systems. The behaviour change wheel begins by understanding the behaviour that is to be changed in terms of three drivers: capability, opportunity, and motivation. An important point to remember, however, is that the people in a learning health system are constrained by the system itself; changing behaviour often requires changing the system.Reference Seid, Hartley and Margolis122

Some organisations (such as Geisinger – see Box 1) have developed behavioural insight teams. For more on behaviour change approaches, see the Element on audit, feedback, and behaviour change.Reference Ivers, Foy, Dixon-Woods, Brown and Marjanovic123

4.3.7 Evaluation

Learning health systems are expensive and can impact the health of large populations, so it is important to understand how effective and cost-effective they are.

Evaluating learning health systems can be challenging. A recent scoping review of current evidence found no published rigorous evaluation of a learning health system.Reference Zurynski, Smith and Vedovi7 Some effects of a learning system may be unintended, they may manifest only over the very long term, and they may occur in related fields beyond health, such as social care, education, justice, and employment. Traditional randomised controlled trials are often not feasible because the intervention changes rapidly.Reference Foley124 This also makes it difficult to generalise findings. Qualitative evaluation methods can add an additional dimension and can help to understand how the intervention works.Reference Foley124

Failure is itself an important source of learning. For example, it can help others to decide whether and how to join a learning health system. But organisations are generally less enthusiastic about publicising failures than successes,Reference Leviss125 and finding published examples of learning health systems that have failed is difficult.

4.4 Maturity

It is important to understand the degree to which the components of a learning health system are able to achieve a specific objective in a predictable way.Reference Lannon, Schuler and Seid126 Tools to assess the maturity of health IT systemsReference Steiner, Paolino, Thompson and Larson127 have been around for a long time, but Lannon et al.Reference Lannon, Schuler and Seid126 have recently developed a process maturity assessment tool specifically for learning health systems. The tool is a capability maturity grid that covers six domains:

Systems of leadership – a set of methods to encourage a network to perform as a system. Activities focus on defining the system’s purpose, understanding the system, measuring the system, and planning for improvement.

Governance and management – how policies, processes, controls, oversight, norms, and actions are set up, sustained, and regulated.

Quality improvement – systematic and continuous actions towards measurable improvements in outcomes.

Community building and engagement – the structures and processes that enable all stakeholders to become involved.

Data and analytics – collecting, validating, organising, and standardising data relevant to the system’s purpose.

Research – generating knowledge through a range of research methods.

These domains represent characteristics that are likely to ensure high performance.Reference Lannon, Schuler and Seid126 The domains also broadly map onto the building blocks outlined above.

5 Critiques of the Learning Health System Approach

There are numerous examples of learning health systems generating important new knowledge.Reference Horwitz, Kuznetsova and Jones35 For example, the Health Maintenance Organisation (HMO) Research Network has for decades generated high-quality research on topics related to organisation, delivery, and quality of care.Reference Steiner, Paolino, Thompson and Larson127 The REDUCE MRSA collaborative demonstrated in a randomised trial embedded into routine practice that universal decolonisation was more effective than decolonisation of MRSA-positive individuals in reducing bloodstream infections. This was a study that would have required 64 years to do at a typical single hospital, but instead took 18 months and cost less than $3 million.Reference Huang, Septimus and Kleinman128

Despite examples like this, there is a dearth of evidence on the likely return on investment associated with learning health systems.Reference Bindman129 By emphasising that learning health systems are embedded in healthcare delivery, the literature sometimes suggests that they are always low cost or free. In reality, they require upfront and ongoing investment in technological infrastructure, data collection, and training.

An interdisciplinary science is developing around learning health systems,Reference Nonadoption70 as seen by funding calls,Reference Bindman129, Reference Hardie, Horton, Thornton, Home and Pereira130 global communities of practice,Reference Ohno-Machado, Gennari and Murphy61 the formation of new university departments,131 conferences,132 and an academic journal,Reference Friedman133 all helping to move the field forward. In this context, a common critique of the learning health system concept is that because the definition is so broad, it risks being all things to all people – and therefore nothing about it is distinctive. The learning health system literature has been criticised for being detached from existing theory around organisational and social learningReference Milligan and Berta58 and for being insufficiently focused on practical implementation. Conversely, putative learning health systems have been criticised for focusing only on one component of the learning health system (such as making use of big data) or implementing learning health system-type activities only in one area or population. Ideally, a true learning health system would be implemented across the whole system in question and characterised by constant iteration, adaptation, and learning, not static systems.

The gap between ambition and feasibility underlies many of these issues. The framework we have set out in this Element attempts to provide more focus on the challenges around implementation, but the practicalities will be different in each learning health system.

A second challenge for learning health systems relates to data. Data are indisputably at the heart of any learning health system. But they are also its biggest vulnerability. Clinical and operational data are inevitably incomplete, biased, delayed, or otherwise imperfect, since, by definition, learning health systems attempt to learn from data generated during everyday activity, rather than data specifically collected in a high-quality fashion for a particular intervention. A learning health system dependent on faulty data runs a real risk of producing adverse events and suboptimal outcomes. Explicit tests for bias and for data integrity are therefore essential to avoid inadvertently worsening outcomes.

Perhaps the most fundamental critique is that learning health systems may have limited capacity for generating new knowledge or radical systems improvements if they rely on learning from what is being done, rather than promoting innovative, creative tests of what could be done. A high-performing learning health system should therefore strive explicitly to incorporate innovation, creativity, and out-of-the-box thinking through culture change and infrastructure to support rapid testing and learning.

Although experimentation and learning are central to learning health systems, a paradox is that the system-wide, complex, multifaceted nature of learning systems make them in themselves not particularly amenable to rigorous, randomised evaluation. More mixed methods research is required to design methods that can determine whether different types of learning health systems work and, if so, under which circumstances.

6 Conclusions

A learning health system is not another healthcare improvement method. Instead, it is the development of systematic organisational capabilities that enable the routine deployment of multiple improvement methods. As described in this Element, a learning health system depends on:

developing a learning community who can champion the work and foster mutual learning

explicitly recognising the influence of multiple sociotechnical domains and the crucial role played by institutional culture

harnessing data effectively but cautiously, with attention to data quality and gaps

embedding a variety of healthcare improvement and research techniques into routine care

avoiding oversimplification while valuing complexity.

The complexity of healthcare organisations means that no two learning health systems will be the same. A system cannot be lifted and shifted from one organisation to another, and there is no ‘how to’ guide for building them. The framework presented here includes the common sociotechnical components of learning at an organisational level. A toolkit has been developed, based on this framework, to curate tools related to each of these challenges.134

As more health systems begin to implement learning health system components, the research community will need to shift from evaluation of individual improvement efforts towards evaluation of how and why learning health systems succeed or fail at scale.

This Element also makes links to other Elements within the series that can help to deliver a learning health system. Ultimately, the development of a learning health system is a journey that will, by definition, never be complete.

7 Further Reading

Institute of Medicine4 – the first report of the US Institute of Medicine’s roundtable on evidence-based medicine was also the first to put forward a definition of the learning health system.

McGinnis et al.Reference McGinnis, Stuckhardt, Saunders and Smith6 – this book is the culmination of several years of meetings of the US Institute of Medicine’s roundtable on value and science-driven healthcare, which evolved from the roundtable on evidence-based medicine and continued its work on learning health systems for the next six years.

Learning Health SystemsReference Friedman133 – an open-access, peer-reviewed, international journal whose goal is to advance the interdisciplinary area of learning health systems.

Foley et al.Reference Foley and Zahran5 – this report describes the framework for understanding learning health systems that was used to structure this Element.

Hardie et al.Reference Hardie, Horton, Thornton, Home and Pereira130 – the final output of Health Data Research UK’s Better Care Catalyst programme’s policy and insights workstream, which researched the barriers and enablers for implementing learning health systems approaches in the UK.

Zurynski et al.Reference Zurynski, Smith and Vedovi7 – a recent scoping review of current learning health system evidence, published by the Australian Institute of Health Innovation.

Both authors have been involved with planning, drafting, reviewing, and approving this Element. Both authors have approved the final version.

Conflicts of Interest

Leora Horwitz is a member of the Geisinger Health System Scientific Advisory Board.

Acknowledgements

We thank the peer reviewers for their insightful comments and recommendations to improve the Element. A list of peer reviewers is published at www.cambridge.org/IQ-peer-reviewers.

Funding

This Element was funded by THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute, www.thisinstitute.cam.ac.uk). THIS Institute is strengthening the evidence base for improving the quality and safety of healthcare. THIS Institute is supported by a grant to the University of Cambridge from the Health Foundation – an independent charity committed to bringing about better health and healthcare for people in the UK.

About the Authors

Dr Thomas Foley is principal investigator on the Learning Healthcare Project at Newcastle University, adjunct associate professor at University College Dublin Medical School, clinical lead on the Health Service Executive Ireland Community EHR Programme, and a practicing child and adolescent psychiatrist.

Dr Leora Horwitz is director of the Center for Healthcare Innovation and Delivery Science at NYU Langone Health, director of the Division of Healthcare Delivery Science in the Department of Population Health at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, tenured professor of population health and medicine, and a practicing internist.

The online version of this work is published under a Creative Commons licence called CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0). It means that you’re free to reuse this work. In fact, we encourage it. We just ask that you acknowledge THIS Institute as the creator, you don’t distribute a modified version without our permission, and you don’t sell it or use it for any activity that generates revenue without our permission. Ultimately, we want our work to have impact. So if you’ve got a use in mind but you’re not sure it’s allowed, just ask us at [email protected].

The printed version is subject to statutory exceptions and to the provisions of relevant licensing agreements, so you will need written permission from Cambridge University Press to reproduce any part of it.

All versions of this work may contain content reproduced under licence from third parties. You must obtain permission to reproduce this content from these third parties directly.

Editors-in-Chief

Mary Dixon-Woods

THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute)

Mary is Director of THIS Institute and is the Health Foundation Professor of Healthcare Improvement Studies in the Department of Public Health and Primary Care at the University of Cambridge. Mary leads a programme of research focused on healthcare improvement, healthcare ethics, and methodological innovation in studying healthcare.

Graham Martin

THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute)

Graham is Director of Research at THIS Institute, leading applied research programmes and contributing to the institute’s strategy and development. His research interests are in the organisation and delivery of healthcare, and particularly the role of professionals, managers, and patients and the public in efforts at organisational change.

Executive Editor

Katrina Brown

THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute)

Katrina was Communications Manager at THIS Institute, providing editorial expertise to maximise the impact of THIS Institute’s research findings. She managed the project to produce the series until 2023.

Editorial Team

Sonja Marjanovic

RAND Europe

Sonja is Director of RAND Europe’s healthcare innovation, industry, and policy research. Her work provides decision-makers with evidence and insights to support innovation and improvement in healthcare systems, and to support the translation of innovation into societal benefits for healthcare services and population health.

Tom Ling

RAND Europe

Tom is Head of Evaluation at RAND Europe and President of the European Evaluation Society, leading evaluations and applied research focused on the key challenges facing health services. His current health portfolio includes evaluations of the innovation landscape, quality improvement, communities of practice, patient flow, and service transformation.

Ellen Perry

THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute)

Ellen supported the production of the series during 2020–21.

Gemma Petley

THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute)

Gemma is Senior Communications and Editorial Manager at THIS Institute, responsible for overseeing the production and maximising the impact of the series.

Claire Dipple

THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute)

Claire is Editorial Project Manager at THIS Institute, responsible for editing and project managing the series.

About the Series

The past decade has seen enormous growth in both activity and research on improvement in healthcare. This series offers a comprehensive and authoritative set of overviews of the different improvement approaches available, exploring the thinking behind them, examining evidence for each approach, and identifying areas of debate.