51456 results in American studies

Erin L. Thompson, Smashing Statues: The Rise and Fall of America's Public Monuments (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2022, $25.95). Pp. 288. isbn 978 0 3938 6767 1.

-

- Journal:

- Journal of American Studies / Volume 58 / Issue 2 / May 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 January 2025, pp. 315-317

- Print publication:

- May 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

David Bordwell, Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder (New York: Columbia University Press, 2023, $32.00). Pp. 491. isbn 978 0 2312 0659 4.

-

- Journal:

- Journal of American Studies / Volume 58 / Issue 2 / May 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 January 2025, pp. 319-321

- Print publication:

- May 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Matthew Dennis, American Relics and the Politics of Public Memory (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2023, $32.95). Pp. 436. isbn 978 1 6253 4711 4.

-

- Journal:

- Journal of American Studies / Volume 58 / Issue 2 / May 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 January 2025, pp. 321-323

- Print publication:

- May 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

“How Many Black Hippies Do You See?” The Counterculture in Black and White

-

- Journal:

- Journal of American Studies / Volume 58 / Issue 2 / May 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 May 2024, pp. 275-300

- Print publication:

- May 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Daniel Heath Justice and Jean M. O'Brien, eds., Allotment Stories: Indigenous Land Relations under Settler Siege (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2021, $28.00). Pp. 322. isbn 978 1 5179 0876 8.

-

- Journal:

- Journal of American Studies / Volume 58 / Issue 2 / May 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 January 2025, pp. 324-325

- Print publication:

- May 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

AMS volume 58 issue 2 Cover and Front matter

-

- Journal:

- Journal of American Studies / Volume 58 / Issue 2 / May 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 January 2025, pp. f1-f3

- Print publication:

- May 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

The Ethno-economy: Peter Brimelow and the Capitalism of the Far Right

-

- Journal:

- Journal of American Studies / Volume 58 / Issue 2 / May 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 May 2024, pp. 169-192

- Print publication:

- May 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

AMS volume 58 issue 2 Cover and Back matter

-

- Journal:

- Journal of American Studies / Volume 58 / Issue 2 / May 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 January 2025, pp. b1-b2

- Print publication:

- May 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

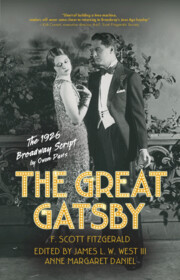

The Great Gatsby: The 1926 Broadway Script

-

- Published online:

- 25 April 2024

- Print publication:

- 25 April 2024

Annotations

-

- Book:

- The Great Gatsby: The 1926 Broadway Script

- Published online:

- 25 April 2024

- Print publication:

- 25 April 2024, pp 100-104

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The Great Gatsby

-

- Book:

- The Great Gatsby: The 1926 Broadway Script

- Published online:

- 25 April 2024

- Print publication:

- 25 April 2024, pp 1-99

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- The Great Gatsby: The 1926 Broadway Script

- Published online:

- 25 April 2024

- Print publication:

- 25 April 2024, pp xii-xxxviii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Note on the Text

-

- Book:

- The Great Gatsby: The 1926 Broadway Script

- Published online:

- 25 April 2024

- Print publication:

- 25 April 2024, pp x-xi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Frontmatter

-

- Book:

- The Great Gatsby: The 1926 Broadway Script

- Published online:

- 25 April 2024

- Print publication:

- 25 April 2024, pp i-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

List of Illustrations

-

- Book:

- The Great Gatsby: The 1926 Broadway Script

- Published online:

- 25 April 2024

- Print publication:

- 25 April 2024, pp viii-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- The Great Gatsby: The 1926 Broadway Script

- Published online:

- 25 April 2024

- Print publication:

- 25 April 2024, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgments

-

- Book:

- The Great Gatsby: The 1926 Broadway Script

- Published online:

- 25 April 2024

- Print publication:

- 25 April 2024, pp ix-ix

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Scopes, Specula, the Speculative: Histories of Medical Experimentation and Looking in African American Art and Fiction

-

- Journal:

- Journal of American Studies / Volume 58 / Issue 3 / July 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 22 April 2024, pp. 327-356

- Print publication:

- July 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

“To Use This Word … Would Be Absurd”: How the Brainwashing Label Threatened and Enabled the Troubled-Teen Industry

-

- Journal:

- Journal of American Studies / Volume 58 / Issue 3 / July 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 16 April 2024, pp. 357-389

- Print publication:

- July 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The “Open Sore of America”: Race and the American Congo Reform Movement, 1885–1908

-

- Journal:

- Journal of American Studies / Volume 58 / Issue 2 / May 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 12 April 2024, pp. 248-274

- Print publication:

- May 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation