On 2 December 1852, Lieutenant Walter May wrote in his journal aboard the Assistance: ‘The last month has passed away pretty quickly – what with theatre, papers &c … I am busily employed at the 2nd number of the Queens [sic] Illuminated Magazine – and also getting up a lot of dissolving views for Xmas.’1 As he wrote, the Assistance was frozen into ever-darkening winter quarters at latitude 77° North in Northumberland Sound, deep in the then-uninhabited northern part of the Canadian archipelago. The quotation is revealing, showing how this lieutenant spent his time on ambitious pictorial projects during the winter, and points to the complex visual culture of the ship. In addition to illustrating a magazine and preparing visual entertainment for Christmas, May painted the scenery for the Queen’s Arctic Theatre, which produced several plays that winter. However, the only tangible evidence that now remains of all his endeavours is the richly illustrated ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine and North Cornwall Gazette’, a hand-produced monthly periodical compiled for the shipboard audience, for which he created both ink drawings and watercolour paintings.2 It is worth emphasising that the periodical included colour illustrations, a novelty for the readers on board that not even the Illustrated London News could compete with at this time.

At least eight periodicals were initiated on British naval expeditions that searched for Franklin between 1848 and 1853. Two of the five surviving periodicals from the search expeditions will be examined in detail here. These two periodicals have been selected for their rich visual material; they contain 127 illustrations between them, which vary from small black-and-white ink drawings to full-page colour illustrations. The ‘Illustrated Arctic News’3 was created on board the Resolute during the winter of 1850 to 1851 and the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine and North Cornwall Gazette’ was handwritten and illustrated on the Pioneer and the Assistance during the winter of 1852 to 1853. The latter exists only as a single manuscript in the British Library. Both titles reference their visual material by using the terms ‘Illustrated’ and ‘Illuminated’, signalling the importance and significance of the visual content to the shipboard community.4 In both periodicals, the prominence of the visual material adds a significant layer of humour and intimacy to the written material.

This chapter shows that these periodicals, particularly in their illustrations, had an emphasis on humour and used the incongruity of the situation as a source of humour, mining everyday Arctic life for comic representations. This was an effective way of negating the Arctic sublime, whether intentional or not. Furthermore, the illustrations show us a focus on the personal, individual, and more domestic side of Arctic exploration, a turning inwards from the summer landscapes produced between May and September. This resulted in an expedition narrative of familiarity and cheerfulness, in contrast to much of the published or exhibited information and entertainment that was circulating in the metropolitan sphere. The general view was that the expedition members (of the Austin voyage from 1850 to 1851) would endure ‘a winter of solemn gloom, and many an unforeseen peril’ before they would ‘look upon merry England again’.5 The shipboard representations challenge modern-day assumptions of the nineteenth-century view of the Arctic, as indeed they would have challenged assumptions during the nineteenth century. The prevailing modern popular narrative around polar exploration of this period still focuses on the hardships of sledge travel, the suffering endured stoically, near-death experiences, and intrepid endeavour, presenting men as both tragic and heroic. Even the titles of early twenty-first-century books, such as Arctic Hell-Ship (2007), The Gates of Hell (2009), and Fatal Passage (2002), which deal with the Franklin searches, contain trigger words that intensify the sublime to attract potential readers.6 Although two of the on-board periodicals appeared shortly after as published books in Britain,7 their version of the Arctic winter was outweighed, or tempered, by the volume of media that suggested otherwise: fixed and moving panoramas, exhibitions, newspaper articles, engravings, lithographs, and some travel narratives written by search expedition members (many of these media forms are discussed in Chapters 3 to 5).

Although it has been observed that periodical production and other cultural activities were an effective way of occupying idle minds in winter, I argue that additional important factors were at play: the periodicals were conceived of as future souvenirs, representing an important connection between expedition members and their Arctic experience. Crucially, the winter period provided the time, space, and even the authorisation to engage in such cultural practices as periodical production. However, the success of the periodicals (being reliant on their readership for contributions) depended on the presence of a lively and large homosocial community isolated from outside contact (both from Britain and from the Indigenous population). The periodicals can also be seen in the context of the wider popularity of magazines, journals, and newspapers that were increasingly consumed by a reading public. The library on the Assistance included periodicals like Dickens’s Household Words (a small unillustrated weekly magazine), Bentley’s Miscellany (a monthly humorous literary magazine), and the Family Herald (a weekly middle-class magazine).8

Several scholars have done important work on the phenomenon of periodicals aboard ships in the Arctic and Antarctica, including those of the Franklin search expeditions. Book historian Elaine Hoag draws attention to the on-board periodicals through her meticulous bibliographical work on shipboard printing, and she clarifies that only one periodical was ever printed on the Franklin search expeditions; the rest were handwritten manuscripts.9 Hoag notes that, although small presses were generally taken on board the search ships, the press on Belcher’s Assistance was large enough to print playbills measuring 43.7 × 34 cm and may have been a second-hand Albion or Columbian half-sheet demy press.10 David and Deirdre Stam investigate the consumption of periodicals aboard ship, suggesting that expedition members read periodicals (including ones they produced) in order to ‘bend time’, giving rhythm to ‘undifferentiated periods of darkness’ while ‘locked in the dark prison of the polar night’.11 Erika Behrisch Elce further argues that the periodicals produced on board were distinct from those brought from home; the former had a ‘richer value’ and provided an ‘intellectual satisfaction’ that distinguished them from other activities available during the winter.12 Periodical production, as well as other cultural activities such as theatrical performances, was encouraged as it was linked to keeping discipline aboard ship, helping to keep sailors visibly busy.13 Crucially, Behrisch Elce observes that such productions are evidence of the importance of the social life of expeditions and argues that the shipboard periodicals, with contributions by both officers and ordinary seamen, show the importance of both reading and writing on expeditions. In their creation of a ‘collective narrative’, they differ from official narratives published in England, giving a far more human and domestic view of life in the Arctic as distinct from the public image of heroic self-sacrifice.14

Hester Blum, in her insightful essay on polar periodicals, remarks how the first Arctic periodicals focused on the ‘local and intimate’ despite the nationalist aims of the expeditions’ endeavour.15 Noting that the periodicals were intended for the private shipboard audience (certain articles were removed before publication), she surmises that they had a different orientation from public accounts such as book-length narratives16 and, like Behrisch Elce, observes that they offer an ‘alternative account of the experiential conditions of polar exploration’.17 More recently, Blum argues in her compelling book, News at the Ends of the Earth, that polar newspapers can be seen as the ‘social media’ of expeditions and that the nineteenth-century Arctic periodicals ‘were a mechanism for sojourners in Arctic winters to comment upon and conceptually orient themselves within the unexpected vicissitudes of polar environmental spaces’.18

While groundbreaking work on the on-board Arctic periodicals has been carried out by literary scholars, it is evident that what has been published understandably focuses on the text of the productions – the illustrations have not been considered in any great detail. By attending to the extensive visual material of the periodicals, we are provided with an even starker ‘alternative account’ of the expeditions that were perceived at the time as being ‘remote from the haunts of men, beset with a thousand dangers, and imprisoned in regions of eternal ice’.19 It is in the illuminating and immediate nature of the illustrations that the life of the expeditions becomes most visible. For example, the cross-dressing that took place for theatrical performances and masquerades is well illustrated in the periodicals, providing a closer look at this common naval practice. Thus, the visual (including its interaction with the text and verbal sketches that create a visual scene in the mind of the reader) is privileged throughout this chapter.

Shipboard Periodicals on British Naval Search Expeditions

The ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’ and the ‘Illustrated Arctic News’ were not the first on-board periodicals produced in the context of Arctic, or indeed polar, exploration. From 1819 to 1820, officers on William Edward Parry’s expedition to the Northwest Passage wrote the ‘New Georgia Gazette or Winter Chronicle’.20 Parry’s was the first expedition to deliberately spend the winter period in the ice, and he arranged for diversions, including the production of a weekly newspaper.21 The idea was subsequently taken up enthusiastically by several expeditions participating in the mid-century Franklin search, particularly by members of the four-ship Austin expedition during 1850 and 1851, when at one stage five periodical titles were in production concurrently. These on-board productions, which were generally, though not exclusively, a feature of the winter period, were mainly handwritten manuscripts produced at weekly or monthly intervals.

While the ‘New Georgia Gazette’ was a text-centric production, the Franklin search expeditions’ output included heavily illustrated periodicals, two of which are examined in this chapter. Unlike Parry’s earlier periodical, those produced by the search vessels encouraged contributions from everyone on board and were designed to be read by, or be read aloud to, the entire ship’s company. For example, John Matthews, boatswain on the Plover, read a copy of the ‘Weekly Guy’ aloud each week.22 While the image of the British sailor is not commonly associated with reading, Blum notes that, by the mid-nineteenth century, literacy among seamen was around 75 to 90 percent.23 The introduction to Arctic Miscellanies (the published version of the periodical ‘Aurora Borealis’ on the Austin expedition) took note that the sailors’ contributions revealed a ‘delicacy of imagination and a power of perception that one has great difficulty in reconciling with the honest roughness of their appearance’.24

The periodicals on the search expeditions were but one facet of the intense cultural and intimate domestic life that also included printing playbills and other documents, elaborate theatre productions, masquerades, concerts, and dances. The number of expeditions, combined with the popularity of cultural production, prohibits an account and examination here of some of these fascinating aspects of expedition culture. These are admirably treated elsewhere, in the work of Elaine Hoag, Heather Davis-Fisch, Heidi Hansson, and others.25 The Arctic environment was key to the cultural production aboard ship, and its portrayal in the periodicals is characterised by an inversion of unconstructive attitudes to winter and darkness, instead representing an Arctic life that was familiar, humorous, and personal. However, these attributes were sometimes lost when the experiences of the expeditions were represented through various media in Britain, and the Arctic often became unfamiliar and depersonalised, a theme that will be further explored in later chapters. It is worth noting here an observation from a sociological and psychological perspective on nineteenth-century voyages to the Arctic: ‘Much of what has been written about voyages to and in the Far North emphasises the vastness, remoteness, strangeness, and dangers of the Arctic. And yet we have many positive reactions to the Arctic in the personal journals.’26 More recently, Lawrence Palinkas and Peter Suedfeld have observed that little research has been done on the ‘positive effects’ of polar expeditions, compared with ‘work that emphasises negative effects and consequences’.27

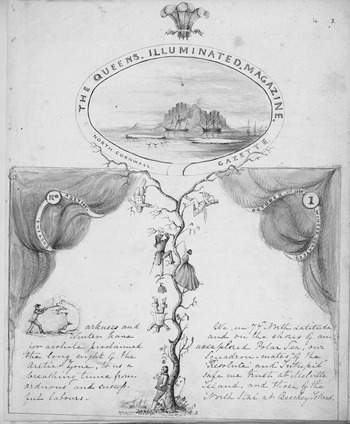

From October, when a search ship intending to winter over was firmly frozen in the ice and the nights lengthened, a metamorphosis took place on the ship, which would last until March. In November 1852, while based at winter quarters as part of the Belcher expedition in Northumberland Sound deep in the Canadian archipelago, Commander Sherard Osborn revealingly began the first page (Figure 2.1) of the new on-board manuscript periodical, the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine and North Cornwall Gazette’, with what reads like a written sigh of relief: ‘Darkness and Winter have for a while proclaimed the long night of the Arctic zone, to us a breathing time from arduous and successful labours.’28 Winter, then, could be a ‘breathing time’, a time and space in which expedition members had room to pause and reflect, and to create. This breathing time was also one that allowed a ‘group-spirit’ to thrive on certain expeditions. As social historian Carolyn Strange has highlighted with reference to studies in present-day Antarctica, an isolated group confined in a potentially dangerous environment perceives that environment as less dangerous if the group gets along and works together well, having an overall positive outlook.29 The use of humour in the periodicals points to a genuine cheerfulness in winter quarters when having a positive outlook contributed to a successful expedition.

Ships overwintering could be immobile in the ice for up to eleven months at a time, and this stasis provided a type of home, complete with supplies and tools that could be used for cultural activities. The periodicals and theatrical performances can in some sense be seen as the arts of immobility, encouraged by their enforced winter sojourn. Under normal circumstances, a naval ship on a surveying mission, for example, would be mobile, requiring the ongoing production of new coastal views and maps and keeping its crew and officers busy with ocean-going duties. The phenomenon of the ship in winter quarters provided a temporary stability, in contrast to the typical seafaring life that lacked ‘firm geographic boundaries or stable residence’.30 For maritime Arctic expeditions, winter quarters had the potential to become ‘the heart of the emotional community’.31 Overwintering expeditions created a space, both materially in terms of the ship as a home and psychologically in terms of the quiet time that the winter darkness provided. This provided expedition members with the space, the time, and even the authorisation32 to partake in a variety of activities beyond the remit of searching, discovery, or science. The ship, in other words, was an entity that became a space of production, which can be regarded in terms of Henri Lefebvre’s ‘social spaces’.33 Thus, ‘space is both produced and productive’.34 This space included the surrounding environment and linkages to other ships in the area, making a cluster of social spaces and a cultural landscape in the Arctic, a temporary community or communities in the local environment.

The handwritten and illustrated manuscript periodicals were produced and circulated aboard, as well as between ships if a group of ships wintered together. At least seven distinct manuscript periodicals and one printed periodical were initiated on British naval expeditions during the period from 1850 to 1853: ‘Flight of the Plover or North Polar Charivari’; ‘Illustrated Arctic News’; ‘Minavilins’; ‘Gleaner’; ‘Arctic Charivari’; ‘Aurora Borealis’; ‘Weekly Guy’; and the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine and North Cornwall Gazette’.35 Only the ‘Weekly Guy’ was actually printed in the Arctic.36 Hoag suggests that deficient typecases and the small size of the on-board presses generally discouraged their use for printing periodicals.37 Walter May remarked in his journal that the necessity of having illustrations in the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’ was one reason not to use the printing press on board.38

Five of the eight periodicals produced by British naval searches for Franklin came from the Austin expedition of 1850 to 1851 (an astounding number of titles even for four ships). Three of those (‘Minavilins’, ‘Gleaner’, and ‘Arctic Charivari’) do not appear to have survived, although a satirical article copied from ‘Arctic Charivari’ exists in Erasmus Ommanney’s papers.39 The ‘Gleaner’ and ‘Minavilins’ (the latter initiated by Clements Markham) were two competing short-lived satirical newspapers of the Resolute and Assistance. ‘Flight of the Plover’ was a four-page manuscript periodical, edited aboard the Plover in 1848 by the ship’s surgeon John Simpson,40 and the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’ was produced during the first winter of the Belcher expedition from 1852 to 1853. At least four of the periodicals were illustrated.41 ‘Aurora Borealis’ contained a number of illustrations,42 as did ‘Minavilins’; the ‘Illustrated Arctic News’ and the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’ were richly illustrated both in colour and monochrome, testifying to the importance of visuality aboard ship and the desire to create and consume visual representations of expedition members’ experiences in the Arctic, including the domesticated and homely side of Arctic life.

The periodicals contained, among other things, reviews of plays and events (which, in the surviving issues, were generally enthusiastic to avoid ill feeling), poems and songs, essays on topics of interest, reports on local Arctic events such as the expedition’s progress, hunting or sledging, amusing illustrations, and mock advertisements. The tone of the periodicals tends to be humorous and gently irreverent, although more serious writing (particularly related to Arctic meteorology or history) and visual material also occurs. Two of the shipboard periodicals were printed and published as books in London on the expedition’s return: the ‘Illustrated Arctic News’ was printed as a lithographed facsimile of the same name in 1852, and selections of ‘Aurora Borealis’ were published as Arctic Miscellanies: A Souvenir of the Late Polar Search (1852).43 The Illustrated Arctic News was priced at twenty-five shillings (about two weeks’ wages for a seaman at the time44), whereas the more modest Arctic Miscellanies (which had far fewer illustrations) cost twelve shillings. A second edition of the latter, which sold for ten shillings and sixpence, was published by Hurst and Blackett when it took over Colburn and Company.

The ‘Illustrated Arctic News’ and the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’ are connected by the involvement of Sherard Osborn (1822–75), a key literary figure in Arctic exploration. Osborn went on his first Arctic expedition in 1850 as lieutenant commanding the Pioneer, a steam tender under the Austin expedition. He co-edited the ‘Illustrated Arctic News’ with George F. McDougall during that winter and continued his literary interests during the Belcher expedition of 1852 to 1854, when he led the Pioneer as commander and produced the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’ with Walter May. He was also the manager of the ‘Arctic Philharmonic Entertainments’ on board the Pioneer.45 He clashed with Edward Belcher to the extent that he found himself in the brig in early 1854 while the ships were still in the Arctic. After his return from his ‘cruise with that rascal Belcher’, he felt that his naval career was at an end: ‘My naval career I feel is over. I had an object and honourable ambition once – it’s gone now. I live merely for myself now and it is little I want.’46 However, he subsequently led a fleet of ships to China in 1857 aboard the Furious. Samuel Gurney Cresswell, an artist and fellow Arctic officer serving under Osborn in the expedition to China, described Osborn in a letter home as ‘a great man, a philosopher’.47 Osborn wrote several books, including Stray Leaves from an Arctic Journal (1852), a light-hearted account of the Austin voyage that I further examine in Chapter 3.

The illustrations in the ‘Illustrated Arctic News’ were produced by George F. McDougall (1821–76), the second master on the Resolute on the Austin voyage of 1850 to 1851. He returned to the Arctic as master of the Resolute with Captain Henry Kellett in command during the Belcher expedition of 1852 to 1854, when he was on the management committee of the Royal Arctic Theatre.48 Lieutenant John Bertie Cator, commanding Intrepid on the Austin expedition, held an unflattering view of McDougall as ‘conceited, opinionated’ and judged him to be ‘one of the laziest fellows I ever met, a great lubber and a nervous fellow’, although he conceded ‘one thing he does very nicely is chart making and etching’.49 McDougall published a narrative of his experiences on his second Arctic expedition: The Eventful Voyage of H.M.S. Resolute to the Arctic Regions (1857), which is also looked at in Chapter 3.

Although none of the illustrations in the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’ is signed, all the available evidence points to Walter William May (1831–96) as the artist. May’s first Arctic expedition was with Austin when he served as mate on the Assistance from 1850 to 1851. Like McDougall and Osborn, the Belcher expedition of 1852 to 1854 was his second Arctic voyage. He served directly under Belcher as second lieutenant on the Assistance, spending the first winter producing much visual material for consumption aboard the ship. His sketches that depicted the progress of the expedition were published as fourteen lithographs in 1855 after the Belcher expedition returned, and he is responsible for some of the drawings that were engraved for Francis McClintock’s narrative Voyage of the ‘Fox’ (1859).50 However, his journal kept on the Belcher voyage shows his increasing discontentment with his superiors during the second winter, complaining of the ‘depraved state’ of Belcher’s mind.51 According to naval historian Andrew Lambert, Belcher had a ‘tempestuous, confrontational leadership’ style that was not suited to the ‘close confinement of a polar winter’.52 May went on to leave the navy and became a successful marine painter and watercolourist.53 I examine more of his paintings and drawings from the Arctic, as well as his lithographs, A Series of Fourteen Sketches Made during the Voyage up Wellington Channel,54 in Chapter 5.

Both the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’ and the Illustrated Arctic News are large-format folio productions measuring over 30 cm in height.55 This is in contrast to many weekly publications, such as the London Journal and Chambers’s Edinburgh Journal, but is more similar to the Illustrated London News. It is conceivable that the large folio format was chosen for use within the domestic space of the ship (reading aloud to a group) and so that illustrations could be shown to full advantage. The Illustrated Arctic News facsimile, in its title, played on the Illustrated London News, although this was not necessarily reflected in its contents. It contains seventy-two monochrome and colour illustrations on fifty-six pages. In the absence of access to the original manuscript version (which I was unable to locate),56 the discussion here focuses on the lithographed facsimile. The original periodical was produced monthly, with five issues in total, beginning on 31 October 1850 and ending on 14 March 1851. Four numbers and a supplement of the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine and North Cornwall Gazette’ appeared from November 1852 to February 1853, during the first winter that the Belcher expedition spent in the Arctic. No periodical was produced during the second winter.57 Magazines, produced weekly or monthly, proliferated during the Victorian period.58 The term ‘magazine’ implies flexibility in the contents and a product more likely to entertain rather than inform its special-interest readers.59 The first part of the title (‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’) indicates variety and colour illustrations, yet the specificity of ‘North Cornwall Gazette’ alludes to a type of newspaper intended for a local and immediate readership, in this case the isolated audience on the Assistance and the Pioneer. The author of the printed advertisement for the magazine did not expect to have any news to deliver owing to their isolated situation, explaining the use of the term ‘magazine’ thus:

The frozen state of the roads, the injury caused to the Electric Telegraph by the recent storms, and frost, and the breaking down of the Transatlantic line of steamers obliges us to depend, for foreign, and country intelligence, to the sole source left us of Balloons and Carrier Pigeons. We feel therefore, driven to adopt the term Magazine. Though we do not in doing so, aim at any very lofty position, in the catalogue of such publications.60

This kind of joking about their isolated situation sets the tone for the entire production, using the Arctic environment as a source of humour. Issues were between twenty and thirty-two pages in length, and the supplement was ten pages long. The January number, including its supplement, was an impressive forty-two pages in length. The magazine was heavily illustrated, containing fifty-five distinct illustrations, fourteen of them in colour, in a total of 103 pages. The ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’ had almost double the number of pages compared to the published version of the ‘Illustrated Arctic News’, suggesting either that it had a larger number of contributions, or that a significant amount of material was excised from the latter prior to its publication.

While the identity of the illustrator is not explicitly mentioned in the magazine and the pictorial material is unsigned, many of the drawings and paintings show May’s confident hand, and some compositions are similar to his lithographs.61 Osborn and May had been friends on the Austin expedition, and McDougall, Osborn’s previous artistic collaborator on the ‘Illustrated Arctic News’, was then several hundred miles to the east, in winter quarters off Melville Island with Kellett’s arm of the squadron. In May’s journal, written aboard the Assistance that winter, he mentions the illustrations on several occasions, lending weight to the certainty that he is the main illustrator. Initially, he remarks that the ‘printing press will not allow us on account of its size and a want of type to print the paper – besides the illustrations will have to be done which could not be put in if printed’.62 May’s comment signals the importance of the illustrations, which were conceived of as being integral to the production. On 8 November, he wrote: ‘I finished the illustrations of the paper yesterday’,63 indicating that he is the illustrator of the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’.

In the early 1850s, illustrated periodicals, such as Punch, Illustrated London News, and Reynold’s Miscellany, were well established yet the mainly wood-engraved illustrations were still regarded as a novelty. Black-and-white illustration became more widely used in the 1860s, but it was not until the 1880s, when printing techniques advanced, that illustration became commonplace.64 So, the illustrated on-board periodicals, particularly the fact that some included colour illustrations, must have appeared novel to their Arctic readers, given their representation of the expedition members’ own lives in the Arctic. The visual dimension is therefore of huge importance to both these periodicals. While in some instances the pictures in these periodicals serve to illustrate the text, thereby visually elaborating, in other cases the visual is prioritised and the text takes its lead from the pictorial representation, thus showing the centrality of the illustration to expedition life and the importance of pictorial self-representation of expedition members. The front page of each issue is well illustrated, and the placement of illustrations at the top of the page shows their dominance.

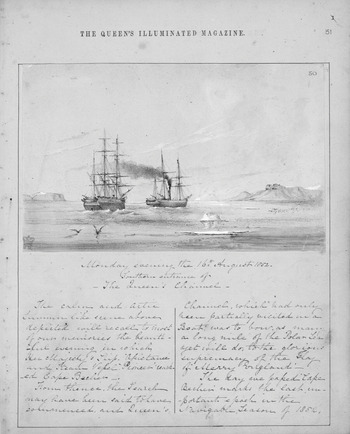

Larger watercolours in the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’ (measuring up to 16 × 23.5 cm), such as Monday Evening the 16th August 1852 (Figure 2.2), were created separately and affixed to the manuscript.65 These appear on the title page of three of the issues and show the appreciation and recognition of May’s talents, which appear to have motivated some of the written material in the magazine. For example, the author of the text below Monday Evening undoubtedly saw May’s watercolours from the summer season, which triggered his written work about events that had taken place six months previously. Monday Evening shows a benign Arctic with blue skies. Its composition is balanced with a delicate use of colour and confident, loose lines. The written piece takes the picture as its starting point: ‘The calm and [Arctic?] summer like scene above depicted will recall to most of our memories the beautiful evening in which Her Majesty’s Ship “Assistance” and steam vessel “Pioneer” reached Cape Becher.’66 The picture is later revisited as a reference point in the same article, highlighting its centrality to the text: ‘However, to return to our frontispiece, within twenty four hours’67 and ‘Those who look upon the somewhat sunny scene the Illuminator has given’.68

Likewise, the ‘Illustrated Arctic News’ regarded visuality as a core part of the production. The full-page colour illustration (42 × 26.8 cm) by McDougall showing a masquerade ball on the Resolute in December 1850 takes a central position in an issue of the Illustrated Arctic News. It depicts sixty characters at the occasion, in full costume, making it possible for those involved to recognise themselves (as recorded by the ‘Aurora Borealis’) and showing that the visual element in the manuscripts is integral and paramount:

With a feeling of pleasure not altogether devoid of vanity, each saw, as in a mirror, a true representation of himself, figuring in the joyous crowd.

We thank the artist for his able efforts, and with the hope that other opportunities may present themselves to exercise his faithful pencil we loudly cry ‘Success to “‘The Illustrated Arctic News”.’69

At least eleven men are shown dressed as women in the picture. Expedition members regularly dressed as women to take female roles in the on-board theatre productions and also for masquerades or other occasions when fancy dress was approved. In the absence of actual women in the domestic space of the ship, the men also took to making elaborate costumes on survey expeditions and in connection with the Franklin searches.70 The practice of cross-dressing, particularly female impersonation on the stage and in music halls, was popular in the nineteenth century, and men often played the parts of women in amateur theatricals.71 As Davis-Fisch points out, in the play Zero, which was written and performed during the Austin expedition (1850–1), the two female characters, Daylight and North Polar Star, are ‘aligned with domesticity and sentimentality, locating desire as something to be deferred until the return home’.72 However, the figures in McDougall’s picture card have very ‘womanly’ bodies, with obvious bosoms and narrow waists, and even dance with men who gaze at them fondly (at the bottom of the picture card). These women do not appear to fit into the category of the pantomime ‘dame’, who was a comedic ‘ugly’ woman without sexual allure. In the picture, at least, attempts to imitate idealised femininity, a tradition that became associated with homosexuality, are evident.73 The term ‘homosexual’ did not enter discourse in Europe and America until the last third of the nineteenth century.74 In the 1870s theatre was linked with transvestism and homosexuality and by the early twentieth century ‘cross-dressing signified sexual-outlawry’.75 However, the presence of so many men dressed as women in the on-board periodicals shows its wide acceptance as part of naval culture in the mid-Victorian period.

Arctic Humour

Winter in the Arctic, particularly in the uninhabited parts of the northern Canadian archipelago, was a time for turning inwards, a time when the focus naturally shifted from the wider natural environment and towards people and personalities on board the ship. The illustrated periodicals, with their heavy emphasis on humour and the human figure in everyday situations, reflect that seasonal change in a way that visual material produced for the general public did not. The illustrations concentrate on the personal, the individual, the domestic, and the social – revealing the proximity of personalities and the social space of the ship during the winter – whereas the Arctic of popular imagination in the metropole was largely expressionless, peopled only by individuals who were indistinct figures in a vast Gothic landscape.

This intimate Arctic space was not one with which the general public, used to scanning the wide Arctic horizon of panoramas and of the geographical imagination, was familiar. When figures were included in graphic material for public consumption, for example in the panorama Summer and Winter Views of the Polar Regions (1850) or lithographs like those of May and Cresswell, they tended to be engaged in outdoor masculine physical activity.76 The Arctic of the periodicals was not sublime, heroic, or astonishing, but familiar, personal, and sociable. The periodical illustrations produced for consumption on board, some of them bursting with characters, emphasise the sociability and warmth that could exist on and between ships.

Close scrutiny of the hand-drawn illustrations in the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’ reveals a myriad of smiling faces, like those in the audience watching The Rival Lovers at the ‘Queen’s Philharmonic Society’ on Pioneer (Figure 2.3).77 It is furthermore interesting that this view is shown from backstage, looking out at the audience, perhaps where Walter May, who painted the theatrical sets, would have stood, and demonstrating not only the centrality of the theatre to Arctic life but also the social aspects of the gathering that went on until around midnight.78 The inclusion of the backstage figures on either side of the scene marks out the theatre performance as something that was produced as well as performed. By showing the event in this manner, he creates a drawing as much for those who were involved in the preparations as for the audience, emphasising the shared intimacy of Arctic life.

Another pen and ink illustration in the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’, captioned Now! o—ne, two—o, three – Haul! (11.5 × 9.3 cm), shows two seamen attempting to help an actor close a dress for the theatre production.79 Here, not only the idea of a crewmember in women’s clothing provides amusement, but the fact that the seamen on either side, used to a type of hauling more maritime in nature, are now acting as maids for the ‘lady’. This good cheer and vibrant social life that was possible during winter on well-organised expeditions (ill-prepared expeditions more often suffered from ill-health and cold and were prone to disaster) was noted by Clements Markham, midshipman on the Austin expedition from 1850 to 1851, who concluded privately in his journal that ‘it became evident that all were determined to pass a regular jolly winter – in fact the dinners, parties, & c, were rather carried to an excess, & left little time for anything else’.80 Markham did not include this comment in his published version of events, where he was far more restrained in his descriptions of amusements, emphasising that they were ‘absolutely necessary … to drive away ennui that might otherwise have seriously injured both the bodily and mental health of the Expedition’.81

The space and time provided by the winter allowed for the indulgence in humour with small in-text drawings created for the periodicals. Both illustrations and text in the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’ show an overwhelming emphasis on the comic with a gently satirical edge. Articles and illustrations include mock advertisements, long letters of feigned outrage, and cartoons. These can be seen to combine to form a type of product similar to Victorian comic magazines that had become popular in the 1840s, such as George Cruikshank’s Table-Book (1845), Punch, or the London Charivari (1841), and the Man in the Moon (1847). Two of the periodicals from the search expeditions (‘Flight of the Plover or North Polar Charivari’ and ‘Arctic Charivari’) even used their titles to reference Punch, which in turn took its inspiration from the French satirical magazine Le Charivari.82 Indeed, Punch, which was hugely influential during this period, was, at the time of the departure of Franklin in 1845, ‘the most talked-about and enjoyed periodical of its time’.83 George Cruikshank’s Table-Book (1845) was included in the on-board library of the Assistance, and its steel and wood engravings may have provided some of the inspiration for both text and illustrations in the Arctic periodicals.84 The Table-Book included contributions by members of the Punch staff and featured essays, sketches, and comic tales, while satirising social issues.85 The style and layout of the drawings in particular is comparable. The figures of women that appear in the Arctic periodicals could well have been based on those in this book. Indeed, on Rochfort Maguire’s expedition, in 1852, the newspaper’s editor, John Simpson, was given Cruikshank engravings by John Barrow to accompany the ‘Weekly Guy’, a projected periodical of the Plover.86 Crucially, where the comic content of the ‘Illustrated Arctic News’ and the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’ differ is that they satirise themselves (by making fun of their situation) and not other sectors of society.

In terms of the visual content of both periodicals, a substantial proportion of the illustrations is based on humorous interpretations of, and responses to, their situation. Twenty-seven, or over one-third, of the illustrations in the Illustrated Arctic News take a humorous angle, having expedition members as their primary subject matter. Fourteen of the drawings, less than a fifth, are landscapes or seascapes, and only one drawing shows any explicit danger. Over half, or twenty-nine, of the fifty-five illustrations in the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’ are humorous, and the majority of them place an emphasis on domestic Arctic life focusing on figures, both human and animal, rather than on landscapes. One-fifth of the pictures in the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’ are landscapes or seascapes. The amount of humorous drawings far exceeds any other category, such as seascapes or icescapes (ten), maritime subjects (eight), meteorology (five), landscapes (three), or dangerous situations (three).

The illustrators and writers repeatedly use personification, a recurring element of Victorian humour,87 but in a way that is specific to the Arctic environment. For the expedition members, particularly those who had been on more than one expedition, the Arctic was not sublime, it was familiar. As Ann Colley discusses with respect to tourism in the Alps after the mid-nineteenth century, familiarity erodes the sublime experience.88 Thus, factors like extreme cold, meteorological peculiarities, and wild animals were part of a domestic life that was easily mined for comic effect. This also had the result of upending any sublimity in these collective narratives. The illustrations in particular broke the Arctic down into manageable portions of humour, with personification being repeatedly employed; the sun (‘this red-faced beggar’), cold, and the aurora borealis were all given animated roles, presenting them in ‘homely terms’, as Max Keith Sutton notes was typical of Victorian comic personification.89 Furthermore, their Arctic world, and their curious existence, while perhaps often spoken of as barren and dreary, was bountiful for the exploitation of humour.

As the anthropologist Mary Douglas shows, the joke form depends on the social situation. Furthermore, the joke within a social structure says something pertinent about that structure.90 And what Richard Altick writes about Punch, the influential British comic periodical that began in 1841, can equally be applied to a consideration of humour, particularly visual humour, in the Arctic periodicals: ‘Comedy is not necessarily incompatible with truth; signifiers in the comic mode, caricatures above all, may tell us as much about the signified as do more serious ones.’91 In fact, the on-board periodicals can be seen to confirm and help build the identity of those on board.92 The humour in the periodicals could best be enjoyed and appreciated by the on-board audience as a distinct social group. This humour, in both illustrations and text, simultaneously stressed specific concerns of the group, much in the same way that modern subcultural comics do, ‘without directly attacking or offending any particular group in the subculture’.93

While satires in the second half of the nineteenth century made fun of tourists seeking the sublime in the Alps,94 the writers and illustrators of these on-board periodicals satirised themselves, the idea of terror, and the metropolitan Arctic imaginary. The perception of the Arctic’s association with the sublime and with horror was gently ridiculed in a lengthy piece in the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’ when the author described a stormy Arctic night during the expedition. As ‘fresh reports of … narrow escapes from being frozen to death or carried off by lean and hungry bears’ were brought in, ‘the good ship trembled to her keel’, and the crew, with ‘horror-stricken countenances’, faced ‘the inevitable doom of being frozen to death’.95 The narrator was then momentarily awakened by the bedclothes falling off before being later roused by his steward to discover it was a nightmare: ‘Reader I had had tripe for dinner the day before, & all this was a nightmare. May not this account for much we read of? Crackling Auroras, Bears’ Nests.’96

At the top right of the essay, a small note reads ‘A quiz upon the Voyage of the Terror 1837’, referring to the expedition to discover the Northwest Passage commanded by George Back. This expedition, which had spent a winter under severe pressure from the ice, had been described in Back’s Narrative of an Expedition in H.M.S. Terror (1838). The phrase in the magazine, ‘the good ship trembled to her keel’, recalls Back’s narrative in which the Terror frequently trembled under pressure from the ice, including ‘some severe shocks, which made her tremble to her very keel’.97 In addition, the quartermaster tells the narrator of the essay that it was the ‘most awfullest night, Sir, I ever saw, just like them they had in the xxxxxx’.98 This lengthy contribution to the magazine, which includes a reference to an ‘Ancient Mariner’ who speaks in ‘sepulchral tones’,99 was illustrated with a watercolour Snow Drift Feb, 15/53 and a small drawing of a hapless-looking figure dressed in his sealskins (Figure 2.4): ‘Suddenly I heard a voice from the Crow’s Nest, sounding above the tumult – “They smells them there sealskins and they’re a coming!”’100

The grim Arctic calamity was described in a visual way, creating a scene of horror that was exaggerated for comic effect. A polar bear with eyes glaring like a ‘whale-oil lamp’ and the ‘champing of her tusks … like the clash of a portcullis’ ran at the narrator.101 The Arctic sublime – the perception of polar exploration in the public mind – is here used before it is abruptly upended by a simple case of indigestion. This ultimate overturning of sublimity appears to poke fun at Arctic exploits and the idea of the heroic explorer, here merely a slumbering officer whose bedclothes have fallen off. Furthermore, the writing mocks the narrative of George Back while the inclusion of the ‘Ancient Mariner’ alludes to Coleridge’s poem and its association of ice with supernatural disaster. The scenes described are all the more interesting given that, by the time this piece was written, Franklin had been missing for seven years. Moreover, three graves of Franklin’s men were discovered in the summer of 1850; indeed, the phrase ‘horror-stricken countenances’ brings to mind the photographs of the dead men in the book Frozen in Time: The Fate of the Franklin Expedition (1987).102 It is unlikely that the essay by ‘A Dreamer’ would have remained had the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’ been published, particularly as the fate of the Franklin expedition had been uncovered by the time Belcher’s expedition returned to Britain in 1854.

Mock advertisements were also used to see the funny side of things. For example, in the first issue, an ‘adventurer’ placed a ‘Wanted’ advert seeking a new home near London with a ‘cheerful prospect embracing at least a dozen trees, some grass, and one cow’. The advertiser was open to an exchange with ‘any gentleman seeking solitudes and a bracing climate, both of which are procurable by enquiring at No. 2 Pioneer Plains’.103 The language is deadpan; the improbability of just ‘one cow’ appearing in a pastoral vista underscores the ridiculous nature of the request.104 Although the page itself is devoid of illustration, the advertisement uses nouns associated with the picturesque, such as ‘prospect’, ‘trees’, and ‘cow’, thus invoking the image of a rural English landscape painting. The advertisement appears to ridicule the idea of the picturesque landscape whereby elements of the real environment could be selected and placed at will to form a pleasing picture. The address given, ‘No. 2 Pioneer Plains’, plays on the ship, the Pioneer, frozen into the sea-ice, but also underlines the relative stability of their situation. Such use of invented addresses was a common feature in contributions to the ‘Illustrated Arctic News’ and the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’. It established a locality in the Arctic ice, combining personalities, landscape features, and ships. An advertisement that appeared in the final issue marked the coming season of arduous travel, jarring against the image of the heroically sublime endeavour of hauling sledges to search for Franklin: ‘Wanted by a person about to proceed on a long journey – a good pair of legs – his own being somewhat out of condition, and that great distinguishing feature, the calves, are supposed to have left for Cape Farewell.’105

The small ink drawing The Defeat of Zero! (Figure 2.5) shows the Arctic winter personified in the hooded and cloaked figure of Zero, who carries an oversized barometer with icy fingers, much like Death carrying a scythe, being pursued by four enthusiastic casks of beer. They jostle each other, running after Zero on improbably spindly legs as the foremost cask hits the grotesque figure with a tankard. The incongruous nature of the rotund barrels racing after a cloaked figure depletes the possibilities of the sublime. Here, cold and possible death are defeated by animated everyday objects. The cartoon was probably inspired by the on-board brewing endeavour that was set up,106 while the figure of Zero was developed from May’s experience on the Austin expedition, when an entire pantomime, Zero, was written and performed especially for the character.107

The ‘Illustrated Arctic News’ too made use of humour to amuse its readers. A comic sketch shows an expedition member regarding the snow sculpture of Britannia on the ice and is captioned Oh! So You Rule the Waves – Do You. Ah! A devilish easy berth you’ll have of it this winter.108 The illustration and its caption show the ability of the naval officers to make fun of imperial aspirations, the British Empire, and the nature of the Royal Navy. In fact, it seems to undermine the authority of the Royal Navy by immobilising it. It also shows the elaborate sculptures of a ‘Walhalla’,109 a humorous allusion that refers to the hall of fame containing busts and plaques of significant German-speaking people, which was completed in Bavaria 1842 by King Ludwig I and had been admired in England.110 In the background, the ships covered in for winter, connected by a series of pillars, show the familiar Arctic scene of winter quarters. Scenes of ships in their winter quarters were commonly associated with the romantic sublime, yet here any possibility of the sublime is overturned by the joke.

The reality of day-to-day life in the Arctic may have inspired the cartoon Northern Sports – Tumbling on the Ice by McDougall that appears in the March issue of the Illustrated Arctic News. On 6 February 1851, William Henry Browne slipped on the ice and fractured his radius. The surgeon, Abraham Bradford, kept detailed notes on the lieutenant’s progress and administered opium to ease any pain.111 Once again, the illustration uses circumstances and local events from which to draw a comic response. The men, rather than conquering the Arctic environment, are transformed into helpless children who flail about in a bizarre situation. This emphasis on humour for collective, yet selective, viewing (those participating in the expedition) is far removed from the romantic introspection of some of the watercolours and drawings, like those of Robert Dawes Aldrich discussed in Chapter 1, which may indicate the more personal use intended for the latter. The emphasis on comedy in the periodicals suggests that they were an outlet for comic interpretations of their situation, something that, given the gravity of the search for Franklin, neither scientific articles nor published narratives allowed. The writing and drawings in the periodicals represent another form of personal response to the Arctic, something for which there was no room in official reports.

Although the idea of the periodical was brought from Britain, the Arctic expedition’s periodical had its own separate identity, and the ice-bound ship in the Arctic environment proved to be a rich source of humour that was prioritised in both text and illustration. The incongruous nature of the situation in which the men found themselves provided a productive seam of inspiration for a form of humour that effectively negated the sublime. Indeed, the terror of the sublime was even gently mocked as a side effect of indigestion in one article. The British naval Arctic expedition members viewed the Arctic as a familiar place, one where novel aspects of the unfamiliar environment became everyday normalities to be incorporated and used for humorous intent in the periodicals.

Function and Readership

Both Stam and Stam and Behrisch Elce discuss the reading of periodicals as tools of naval discipline, intended to keep potentially idle hands occupied over the winter period in the Arctic.112 As Behrisch Elce notes, this was only one function of their production and the act of writing the periodicals was as important as reading them.113 Although captains may have encouraged activities such as periodical production and theatre performances to allay boredom, these practices were by no means universal on the British naval expeditions during the Franklin search. Captain Robert McClure’s ship, the Investigator, spent three winters in an area that can be described as isolated, even by Arctic standards, on the north coast of Banks Island from 1850 to 1853. McClure used lashing to enforce discipline, and, although a seamen’s school was organised during the first winter, little else was done to alleviate the boredom. During the third winter, with provisions running short, Johann Miertsching (the expedition’s translator) writes that ‘everyone has learnt knitting or crocheting to shorten the long fearful hours’.114 There are no records of members of the Ross expedition from 1848 to 1849 engaging in performance, and neither was a periodical produced, although Edward Adams, William Browne, and Cresswell painted during the voyage.115

Additionally, the reality of creative practice, and periodical production in particular, seemed to depend on the presence of certain driving actors. For example, on the Austin expedition, which had five periodicals, there were key figures, such as Osborn, McDougall, Ommanney, Markham, Frederick Krabbé, Charles Ede, and William Dean, who were instrumental in initiating and sustaining cultural activities. Expedition members on the four ships of the Austin expedition were able to feed off each other’s enthusiasm and verve, exchange ideas, and cooperate in projects while also lending a competitive element to activities. The periodical ‘Minavilins’ was established on board the Assistance, so as not to be outdone by ‘Gleaner’ on the Resolute. ‘Minavilins’ intended to ‘keep a sharp watch on the Gleaner’, whose editors remained incognito.116 It seems to be the case that a creative cluster, consisting of several talented and enthusiastic individuals, formed on this expedition, and that this grouping drew in other expedition members, lending creativity a contagious effect and leading to the extensive cultural production. Unlike metropolitan periodicals, the Arctic productions generated and benefited from instantaneous reader reaction within the close-knit community aboard ship, which must have provided additional stimulus for contributors and editors.117

Neither was periodical production confined solely to winter, as has been generally assumed. While the production of the periodicals was, like theatre, primarily a winter pursuit, they were not always limited to that season from November to February.118 The four issues of ‘Flight of the Plover’ that survive are dated from 1 March to 1 June 1848.119 The first issue of ‘Aurora Borealis’, the newspaper of the Assistance on the Austin expedition, was produced in June 1850, followed by monthly issues from September 1850 through to March 1851, with a final issue produced in September 1851, showing us that interest in creating and reading the periodical could go beyond the mere necessity of amusing and occupying the crew members during the three darkest months of winter from November to February.

Given the tone of the ‘Illustrated Arctic News’ and the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’, one can only speculate on the probably more extreme contents of two short-lived satirical newspapers of the Austin expedition, ‘Minavilins’ and ‘Gleaner’, which were quashed by superiors.120 The ‘Gleaner’, edited anonymously, had ‘a humorous tendency’, and its second issue included ‘a scurrilous … attack on one of the officers of the expedition’. The answering article in ‘Minavilins’ used ‘scathing satire’ and ‘several humorous illustrations’ in its reply.121 Hence, the quashed periodicals likely crossed the fine line between humour and offensiveness. Perhaps originally conceived as an occupation for potentially idle hands, the periodicals could in fact become vehicles for veiled criticism and even open hostility.

The Austin expedition of 1850, with its exclusively homosocial environment in winter quarters far removed from any contact with Indigenous settlements, is remarkable simply for the quantity of surviving documents in the archive that pay testament to the enthusiasm of its members for engaging in periodical production and other cultural activities. As Blum notes, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the percentage of on-board periodicals produced on polar expeditions was far higher than on non-polar voyages.122 Even accounting for the material that is unlocated (at least three shipboard periodicals), a large amount of material remains. One distinguishing feature of this expedition in the winter of 1850 to 1851 was its location near Griffith Island, in the centre of the Arctic archipelago and not in the vicinity of any Inuit settlements.123 As well as the four ships comprising the Austin expedition, there was a group of other ships wintering comparatively close by, in nearby Assistance Bay, some twenty miles away or a four-hour journey by dog-sledge.124 These were the Felix with its unmanned tender, the Mary, captained by John Ross, and the Lady Franklin and the Sophia, led by William Penny. This relative proximity led to a cross-fertilisation of ideas between ships and expeditions. For example, Arctic Miscellanies contains letters from Assistance Bay, including an account of their own Royal Cornwallis Theatre, while a seaman from Penny’s expedition provided interval entertainment during the final performance at the theatre on the Assistance.125 The ships of the Austin expedition were frozen in for eleven months, and it is possible that this exclusive homosocial world, without the benefit of social interaction with an Indigenous population, was a significant factor in its intense cultural production.

With the right conditions, especially with the right captain, the Arctic winter became a refuge in which expedition members could experiment and express themselves. The social aspect of so many personalities gathered together could be inspiring: ‘If a James, Ainsworth or Trollope could only spend a winter with us, what [Honey] they might store up for four volumes fictions; indeed so rich a harvest, that we almost feel tempted to begin something with an Esquimaux Title or “How I found myself Frozen in”!’ exclaimed the supplement of the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’.126 This allusion to the contemporary prolific and popular authors who wrote three-volume novels, George Payne Rainsford James,127 William Harrison Ainsworth, and Frances Milton Trollope,128 suggests that a rich and intricate web of personalities and activities was part of life during the winter.

Conversely, ships that wintered near Indigenous communities could have plenty of informal social interaction and correspondingly less time for activities such as writing for a periodical. Expeditions such as that of the Plover (1848–54) benefited from Iñupiat who hunted, shared their knowledge, and created winter clothing. Rochfort Maguire on the Plover relates how exhausted he felt at the end of a long day of social interaction with Iñupiat aboard ship.129 Although the Plover did, during its six-year stay in the Arctic, produce two short-lived periodicals, these were both very small productions that lacked illustrations. The ‘Weekly Guy’ was a small (20 × 16 cm) four-page production that only lasted a few months due to a lack of contributions. The Plover, under the command of Thomas Moore from 1848 to 1852 and captained by Maguire from 1852 to 1854, spent its first winter near the people of the Chukchi Peninsula on the west side of the Bering Strait and subsequent winters near Iñupiat communities of what was then Russian America. Lieutenant William Hulme Hooper’s narrative, Ten Months among the Tents of the Tuski, details extensive contact between the ship and the local population from 1848 to 1849, while Maguire’s journals show that Iñupiat were on board, apparently at their own request, almost every day during the winters of 1852 to 1854.130 Consequently, it seems that social interaction with their neighbours took up much of the crew’s attention and spare time. This included consorting with the local women, as several sources indicate.131

Hoag has observed that, while fewer plays were performed on the Plover than on some other Arctic ships, more masquerade balls and dances took place.132 For example, in February 1853, John Matthews, boatswain, recorded the extent to which they interacted with the crew and officers of the Plover:

I am happy to say the natives now appear to be friendly with us and we give them all the encouragement we can, giving them dances on board. We dress and light up our ship inside and allow them all, men, women and children, to come in, and I think at these times we have all the natives belonging to the village on board, to the number of 120, or more.133

Expedition leaders of the searches in general felt that it was important to maintain the goodwill of Indigenous peoples, who often travelled long distances when hunting, so that they would be more disposed to help members of the lost expedition should they encounter them. With the proximity of Chukchi, Yup’ik, and Iñupiat settlements a feature of winter quarters in the Bering Strait region, there may have been less need for the distractions of an on-board periodical. For these expeditions, which spent more time engaging with Indigenous communities, there was less time available to engage in cultural production.

However, for those ships where periodicals were more popular, there was a tension between the idea of private and public as far as contributors were concerned. Blum suggests that non-contributors to Parry’s endeavour may have feared for their reputations, while contributors felt what was written would stay within their private Arctic society.134 But the practice of the subsequent publishing of the periodicals in Britain, and therefore potentially exposing contributors, also occurred. The ‘New Georgia Gazette’ was published as the North Georgia Gazette, and Winter Chronicle in Parry’s narrative (1821), with some pieces that showed crew tensions excised.135 In this case, the decision to publish was not necessarily made by contributors themselves. Two of the Franklin search productions were also published; the ‘Illustrated Arctic News’ and ‘Aurora Borealis’ were both transformed into books on the return of the Austin expedition. The publication of the latter saw a ‘collection of articles … extracted from a newspaper’ produced as Arctic Miscellanies (1852).136 A handbill advertising Arctic Miscellanies hoped that ‘such a volume will meet with a cordial reception from the public, while there can be no doubt that the Officers and Seamen of the Navy, so much interested in its achievements, will eagerly avail themselves of the opportunity of securing so agreeable a souvenir of the Search in the Polar Seas’.137 Reviews of the Illustrated Arctic News were favourable, with the Era commenting that the expedition members’ ‘handy work’ was ‘not only peculiarly interesting but remarkably clever’. Furthermore, it revealed ‘you learn here more of what transpires among our brave countrymen when they are near the North Pole than a hundred printed books can tell you’.138 The Literary Gazette considered it to be ‘an “Illustrated Punch”, as well as an “Illustrated News”, containing songs and witticisms of no inconsiderable merit’.139 Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper referred to Arctic Miscellanies as a ‘clever little production’.140 The appearance of two of the on-board periodicals in the metropolitan sphere, while significant, was still dwarfed by the sheer amount of other publications and exhibitions – the published narratives, moving and fixed panoramas, lithographs, newspaper articles, and engravings – that told a different story. It was no wonder that the review of the Illustrated Arctic News in the Literary Gazette declared with surprise ‘who would have thought that so much fun and jollity prevailed in the midst of the frozen regions on this occasion!’.141

As evidence of the clear difference between the private, yet collective, space of an Arctic ship in winter and the metropolitan public, a note from Osborn, written on 30 September 1854 at the front of the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’, warned that: ‘This paper must not be published or circulated publicly without the full consent of the contributors’.142 This implies that the periodical was, in the first instance, meant for the private society on board ship and, on their return, could be viewed by select individuals. In 1857, John Barrow inscribed a note below Osborn’s, outlining that Osborn had given him this ‘book’, which was the original ‘and not hitherto printed or published’.143

If the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’ was essentially a private document, intended to be read on the ship, it was also an object that held interest beyond its initial purpose of amusing the expedition members during their Arctic voyage. At the beginning of the enterprise, May signalled his own aspirations for the magazine: ‘I sincerely hope that the paper will be carried out with a good will and be an amusement to us now & something to look at hereafter – that will remind us of old Arctic days.’144 May here projected a future for the production, as a memento that they could regard long after the expedition returned. His words, ‘that will remind us of old Arctic days’, suggest an affection for the Arctic and perhaps even an expectation of feelings of loss in the future. In this way, the periodical was expected to serve an important purpose as a type of memento or souvenir. This would indicate that many expedition members were emotionally invested in the Arctic experience of wintering over. The lack of any marginalia on the pages of the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’ and its good condition suggest its status as a revered object, even from the time of its making.145

Additional souvenirs are suggested by May’s other comments regarding the forthcoming magazine: ‘We published our prospectus for the Victoria Gazette146 by the aid of the printing press – and 80 copies were struck off so that the officers should have two each and the men one copy each.’147 The imprints of the prospectus were produced, not only for immediate consumption aboard ship – after all only a few copies would be needed for that – but expressly so that the men and officers could have souvenirs of their Arctic voyage, again indicating the emotional attachment to their experience. Other instances of this production of numerous copies of imprints, particularly dance announcements and playbills, suggest that the production of such souvenirs on other search ships was common. There is an awareness that they were taking part in an important event and that the ‘old Arctic days’ would inspire nostalgia and sentimentality in the future personal lives of the expedition members. Indeed, within the archived personal journals and papers of expedition members one often finds playbills and printed announcements inserted between the leaves. In Arctic Miscellanies, an article on their printing reveals the importance of these tokens: ‘In the years to come, every little souvenir of our sojourn here will be prized for the recollections it will give rise to – of the comfort and amity that existed among the members of the “Austin Happy Family”.’148 It is notable in this quotation, too, that the period of winter ‘imprisonment’ is referred to as a ‘sojourn’, a descriptor that indicates relative rest as opposed to an ordeal.

The concept of the personal memento intended for private consumption, whether in the form of a periodical or a model sledge,149 and its connections to memory and nostalgia is a thread that runs through many of the expeditions. Thus, periodicals, particularly those that were illustrated, as May’s comments suggest, were produced not only to relieve boredom but also for their potential to be viewed in the future, as a reminder of their winter in the Arctic and the spirit of those on board. In this way, the souvenirs are very different from the idea of one that is representative of ‘the exotic transported across the world’.150 These are more intimate and meaningful souvenirs of the expedition members’ own making and representative of their lived experience in the Arctic.

Conclusion

The final issue of the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’ commented on its ‘overflowing Editor’s box’ as the ‘best proof of success of an Arctic Newspaper’.151 Over the course of the winter, that box attracted some contributions that were never included in the magazine on account of ‘extreme raciness!’.152 Intriguingly, the editor’s box also produced ‘an original Operetta! and an original Pantomime! and both of great merit’,153 all suggestive of the intense cultural production that was possible on isolated overwintering expeditions.

These cultural resources are best exemplified by the on-board newspapers they produced. The use of the Arctic environment as a trigger for humour and the focus of illustrations on the domestic and familiar contrasts with the idea of the Arctic as a testing ground for British masculinity. Although partly modelled on comic magazines like Punch or Cruikshank’s Table-Book, the Arctic newspapers were particular for the subjects that they chose as the targets of their humour: the cold, the aurora, imperialism, polar bears, and the expedition members themselves. In opposition to the imaginary of the Arctic as a barren wasteland, it can be seen to be a fruitful source for humorous exploitation, and the situation of the crew is replete with comic possibilities, thereby negating the Arctic sublime (whether that effect was intentional or not).

This chapter has presented an alternative narrative to the sublime Arctic by looking in detail at two illustrated periodicals during the Arctic winter. Examining the periodicals and related material reveals a strong account of familiarity with the Arctic environment and of appreciating the winter as a time of rest and of cultural production. The ‘prison’, so often mentioned in contemporary and modern publications, could equally be a ‘sojourn’, providing, in the revealing words of Osborn, ‘breathing time’.154 The need to include a supplement with the third issue of the ‘Queen’s Illuminated Magazine’ shows the enthusiasm of contributors and the large quantity of submissions. The periodicals had other important functions in addition to providing amusement for expedition members during the dark winter. Along with some of the other material created on the expeditions, the periodicals were thought of as future mementos, expressing a desire on the part of expedition members to remain connected to each other and to their Arctic experience. Crucially, the winter period on an Arctic search ship facilitated cultural practices like periodical production. Furthermore, periodicals were most successful on ships that were completely isolated from Indigenous communities during the winter. When a large group of ships wintered in the same location, a local competitive element came into play.

The extensive media attention and the production of texts and pictures in Britain during the period of the searches was fuelled by the growing mystery of the loss of the Franklin expedition that captured the public imagination. Cultural products associated with the search, from expedition journals to sketches, had the potential to be transformed into saleable commodities – narratives, lithographs, panoramas – once an expedition returned to Britain. However, the more positive aspects of Arctic life were only partially viewed by the wider public. The following three chapters of the book all focus on the material that was produced in the public domain: narratives, panoramas, and lithographs, as well as representations in metropolitan periodicals.