When I asked a former militia member in Nicoadala district how the Naparama leader Manuel António convinced people to join the movement, he seemed surprised about the question. In his view, the Naparama leader did not have to do anything specific to persuade youths to be initiated into the movement. Community residents repeatedly told me that when Naparama formed, they welcomed the opportunity to contribute to ending the war: “We were tired [of the war]! So we joined [Naparama] voluntarily.”Footnote 1 Potential members did not need particular incentives to join, but volunteered to become militia members: “[Naparama] didn’t receive anything. The people revolted. They were tired of the war, so they preferred volunteering, confronting those who were waging war and ending it.”Footnote 2

With the notion of “being tired of war,” my respondents suggested that the conflict was “ripe” for a community response. Community residents expressed a sense of urgency to respond to the dynamics of the war by forming militias. They perceived the war as “intense” and “hot”; because of frequent attacks, they could not sit down “even for five minutes,” as they constantly had to flee their homes.Footnote 3 Working their land had become impossible, and peasant farmers had become dependent on relief goods.Footnote 4 Seeing only the suffering, they did not understand why the war had to be fought “between brothers” or what could be gained by winning it.Footnote 5

Indeed, in the late 1980s, the war reached a point at which elites on both sides perceived that a military victory was out of sight and that continued fighting was costly. Slowly, a “mutually hurting stalemate” (Zartman Reference Zartman1989) emerged on the national level, which prepared the way for negotiations.Footnote 6 Community residents, however, reluctant to wait for their leaders to end the war, requested immediate change. Why was the time ripe to form a militia? Why did community residents opt for armed defense against insurgent violence at that particular time?

In this chapter, I show that the strategic context of a military stalemate on the local level helped form community-initiated militias. I apply the concept of a “community-empowering stalemate,” introduced in Chapter 2, to show that the military stalemate had two important consequences. First, its violent character made community residents vulnerable and war-weary, as neither side of the conflict was able to protect them. Second, the stalemate implied that a significantly weakened government was incapable of fighting back another armed group in addition to the rebels and thus tolerated the grassroots formation of militias. Local administrations welcomed the militia as a force multiplier, particularly in areas in which the state armed forces had a weak presence. So the community-initiated Naparama militia that originated in the late 1980s in Zambézia and Nampula provinces after a large counteroffensive by Frelimo failed to stop Renamo advances and to restore stability. The militia offered its services to communities and local administrations at a crucial point during the war. In the following, I discuss the emergence of the stalemate in Zambézia and Nampula provinces and then show how it helped form the Naparama militia, first from the perspective of the civilian population and then from the perspective of the local state.

5.1 The Emergence of a Community-Empowering Stalemate

While the Mozambican civil war took place mostly in the center and south of the country between 1976 and 1982, Zambézia and Nampula became important battle grounds from 1982 to 1983 and onward. After Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980, Apartheid South Africa became Renamo’s main external supporter and the rebels further developed political objectives in addition to the military goal of destabilizing Mozambique (see Chapter 4). To achieve these political aims, Zambézia and Nampula became strategically important as they were the most populous provinces in the country and centers of agricultural production. At the time of the war, each province had about three million inhabitants, out of the country’s fifteen million. Zambézia was the source of over 50 percent of Mozambique’s sugar, tea, copra, and coconut production.Footnote 7 Nampula province produced more than 50 percent of the cotton grown in Mozambique. The Nacala corridor that crosses through Nampula province links Malawi to the port of Nacala, one of the best deepwater harbors on the East African coast at the time.Footnote 8

Due to the provinces’ political and economic significance, Renamo made inroads into Zambézia in August 1982 (Legrand Reference Legrand1993, 91–92) and Nampula in April 1983 (Do Rosário Reference Do Rosário2009, 305). When crossing the Zambezi River, Renamo merged with an armed group that had been operating in a limited capacity in eastern Zambézia from 1976 to 1982, the PRM (Hall Reference Hale1990, 40). The PRM had its origins in a nationalist organization of the 1960s, the Rumbezi African National Union (UNAR), which sought to reestablish an independent state – Rombézia – between two rivers, Rovuma in the north and Zambezi in the center of Mozambique (Legrand Reference Legrand1993, 89; Coelho and Vines Reference Coelho1992, 32).Footnote 9 UNAR’s area of activity had been Milange in eastern Zambézia, so the PRM benefited from high levels of support in that region.Footnote 10 The PRM had tactics similar to Renamo’s and targeted the symbols of the Frelimo state: local government officials, teachers, health workers, and state infrastructure such as schools, health posts, administrative buildings, and communal villages (Chichava Reference De Bruin2007, 403). The movement disrupted political life in Milange to such an extent that Frelimo forced people into communal villages to better control them.Footnote 11 The PRM’s alliance with Renamo did not last long, however. Due to conflicts about goals and strategy, the PRM left Renamo in 1987, and later aligned itself with Frelimo.

In the years following its unification with the PRM in 1982, Renamo targeted state and economic infrastructure, set up camps in rural areas, and pillaged people’s belongings in the villages surrounding rebel bases. Zambézia proved “ideal for large-scale rebel operations” (Finnegan Reference Finnegan1992, 71) due to the local political weakness of Frelimo, the porous border to Malawi, and high forestation.Footnote 12 Indeed, in conversations with Lisa Hultman, Renamo leader Afonso Dhlakama and Raul Domingos, Renamo chief of general staff during the war, explained that it was easier to operate in the northern and central provinces than in the south due to its hilly forests and availability of water (Hultman Reference Hultman2009, 831). Renamo established its first bases in Zambézia in the Morrumbala district and in the Namuli mountains near Gurué (Cabrita Reference Cabrita2000, 202–3). The major bases were located in Morrumbala (Alfazema) and Mocuba districts (Namanjavira and Muaquiua) (see map in Figure 5.1). Frelimo estimated that after Renamo’s offensive across the province, 6,000 rebels (of a force of 18,000–20,000) were stationed in Zambézia.Footnote 13

Figure 5.1. Map of district boundaries in Nampula and Zambézia provinces in Mozambique indicating fieldwork sites

Note: Cartography by Sofia Jorges

Both Zambézia and Nampula provinces experienced an escalation of violence in late 1986 when Malawi expelled several thousand Renamo combatants from its territory.Footnote 14 This was part of an ongoing negotiation between the governments of Mozambique, South Africa and Malawi. When the rebels occupied several district towns along the border to Malawi and in Zambézia and Nampula, the Frelimo government feared that the rebels would take control over the north and cut the country in half along the Zambezi valley, to the South of Zambézia province (see map in Figure 5.1).Footnote 15 After Mozambique’s president Samora Machel died in a plane crash in South Africa in 1986, the new government under Joaquim Chissano rejected a negotiated settlement and sought to win the war (Seibert Reference Seibert, Abbink, de Bruijn and van Walraven2003, 271). In late 1986 and early 1987, the Mozambican military, together with allied forces from Zimbabwe and Tanzania, began a counteroffensive in Zambézia province. The beginning of the offensive was marked by the creation of the Advanced Command Post and General Headquarters (Posto de Comando Avançado, PCA) – a joint command of all defense and security forces – in Quelimane in November 1986.Footnote 16 With the help of the PCA and 3,000 Tanzanian soldiers, Frelimo recaptured significant parts of territory and resettled the population into Frelimo-held areas. In January 1987, the first aid convoys reached Alta Zambézia and formerly isolated districts were reconnected to Quelimane.Footnote 17

Although Frelimo’s counteroffensive in 1986 and 1987 returned all district towns to Frelimo control by July 1988, it was not decisive in the war in Zambézia and did not create enduring stability.Footnote 18 Local stalemates emerged in which the government could regain control over the district towns, but many localities remained occupied by Renamo forces and the outskirts of the district towns experienced frequent skirmishes. The radius of action in the district towns remained limited between five and ten miles, and towns and villages suffered from frequent attacks.Footnote 19 Renamo also continued occupying district towns, but it did not hold them much longer than a few days. While the Renamo occupations in various districts in 1985 and 1987 lasted between 300 and 600 days, from 1988 onward, rebel control of towns was much shorter (with the exception of Lugela district) (see Table 5.1).

Table 5.1. Number of days of Renamo occupation of district towns in Zambézia province

| District | Date Occupied by Renamo | Date Reoccupied by Frelimo | Days under Renamo Occupation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1985 | Mopeia | August 6, 1985 | March 7, 1987 | 578 |

| Morrumbala | August 20, 1985 | April 28, 1987 | 616 | |

| Gilé | October 3, 1985 | |||

| 1986 | Namacurra | February 1986 | February 1986 | 3 |

| Milange | September 26, 1986 | June 2, 1988 | 615 | |

| Maganja da Costa | September 27, 1986 | |||

| Namarrói | October 1986 | October 1986 | 3 | |

| Gilé | October 28, 1986 | July 10, 1988 | 621 | |

| Namarrói | December 29, 1986 | December 16, 1987 | 352 | |

| 1987 | Pebane | September 25, 1987 | September 26, 1987 | 1 |

| 1988 | Lugela | August 17, 1988 | December 2, 1988 | 107 |

| Gurué | November 27, 1988 | November 30, 1988 | 3 | |

| 1989 | Ile | February 16, 1989 | February 23, 1989 | 7 |

| Mopeia | June 27, 1989 | July 6, 1989 | 9 | |

| Mopeia | November 15, 1989 | November 20, 1989 | 5 | |

| 1991 | Namarrói | December 1991 | December 1991 | 3 |

| 1992 | Lugela | October 19, 1992 | November 21, 1992 | 33 |

Note: This table is compiled by the author and the evidence is drawn from archival documents, newspaper reports, and interviews. It is not a complete list of Renamo occupation of district capitals in Zambézia, as the exact dates and length of occupation are difficult to determine in many cases. It only serves an illustrative purpose.

The local stalemates that arose were violent ones, resembling a war of attrition. The military situation in Alto Molócuè, the district in Zambézia province that first experienced Naparama activity, was characterized by frequent rebel attacks “with no end in sight” (Pereira Reference Pereira1999a, 58). In the late 1980s, Renamo occupied all rural areas, while Frelimo controlled the main town and the top of the Nauela mountain. Pereira describes this situation as the “conflict’s peak” in the district, at which the conflict appeared “saturated” (Pereira Reference Pereira1999a, 60). Neither Frelimo nor Renamo was able to make significant advances at that particular time in the war.

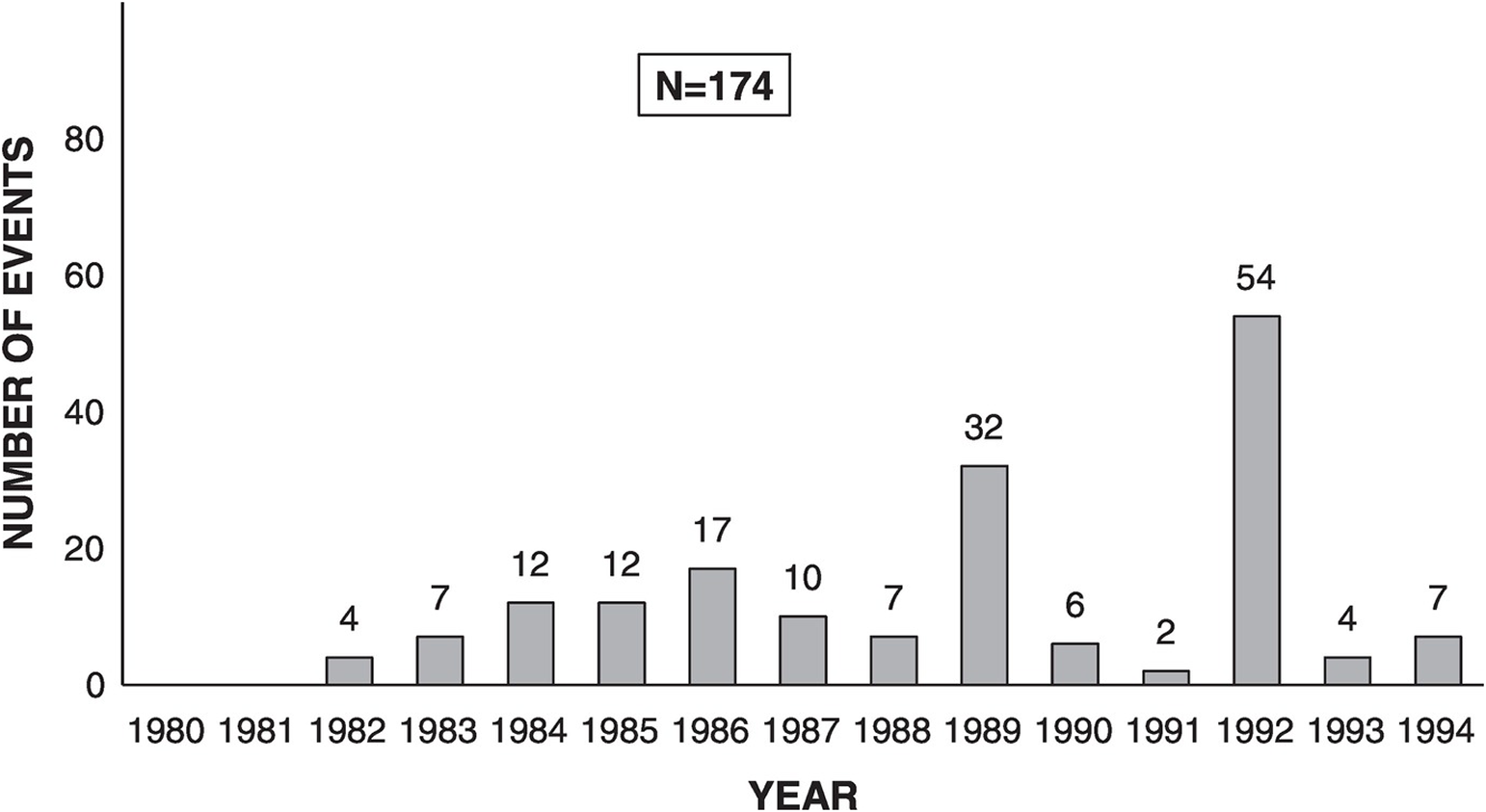

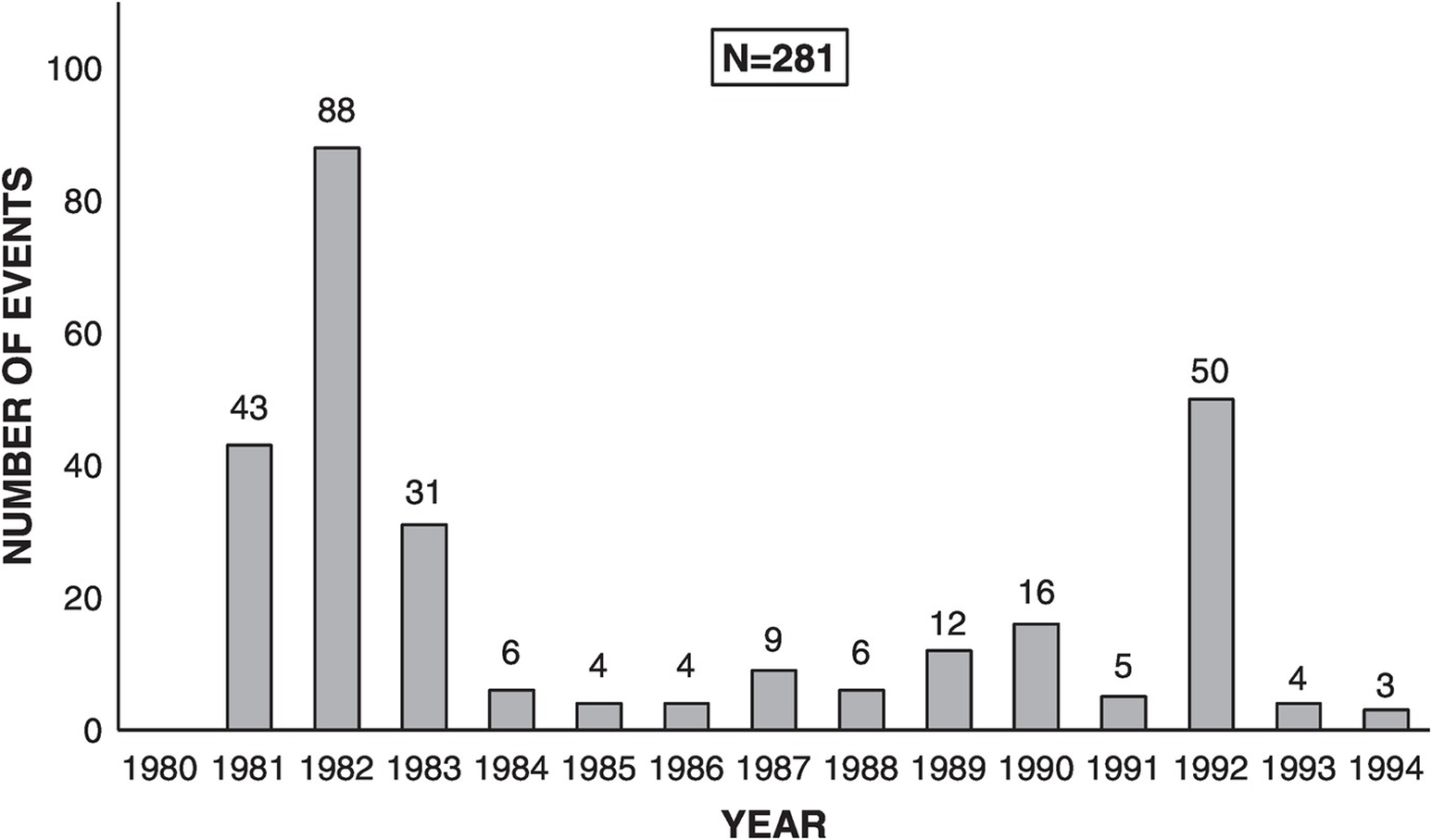

During these local military stalemates, both Frelimo and Renamo combatants committed indiscriminate violence against civilians in the areas under the adversary’s control. The number of violent incidents rose in 1987–89 (Figures 5.2–5.4).Footnote 20 The armed groups considered civilians in contested areas potential enemy collaborators, and thus legitimate targets of violence (Pereira Reference Pereira1999a, 48). Furthermore, due to the lack of material and ammunition, Frelimo and Renamo both preferred attacking the population in the zones under the adversary’s control over fighting direct battles. The war in Zambézia is thus often described as a “war of avoidance” (Legrand Reference Legrand1993, 98).

Figure 5.2. Number of incidents of violence against civilians in Zambézia province, 1980–94, based on newspaper sources

Note: This graph is based on data from Weinstein (Reference Weinstein2007). The types of violent events in Weinstein’s dataset include killing, mutilation, kidnapping, detention, injury, arson, rape, looting, and forced displacement. The events are coded from the reporting by the national newspaper Notícias (Weinstein Reference Weinstein2007). I thank Jeremy Weinstein for kindly sharing his dataset.

Figure 5.3. Number of incidents of violence against civilians in Zambézia province, 1980–94, based on government reports

Note: This graph is based on data coded from provincial and district government reports collected during fieldwork. The events include direct and indirect lethal forms of violence against civilians. See the Appendix for details on the data and coding.

Figure 5.4. Number of battles between government and rebel forces in Zambézia Province, 1980–94, based on government reports

Note: This graph is based on data coded from provincial and district government reports collected during fieldwork. The events include direct confrontations between government and rebel forces with and without changes in territorial control. See the Appendix for details on the data and coding.

The tendency toward indiscriminate violence can be traced on both sides, linking them to the dynamics of war. Although Renamo initially enjoyed some popular support in rural areas, rebel forces increasingly targeted civilians indiscriminately, particularly in those areas they did not control. Many respondents in the districts of Nicoadala, Lugela, and Namarrói told me a similar story: during the first phase of the war, Renamo units selectively targeted Frelimo representatives such as party and state officials, teachers, and health workers. The rebels abducted civilians to transport pillaged goods to Renamo bases or to train youths as combatants, but usually did not kill them. They also mobilized people in the areas they controlled to support them with food and information and set up political administrations in collaboration with local chiefs.Footnote 21

During the second phase of the war, respondents reported that violence became more indiscriminate, and Renamo combatants began to kill civilians without any official ties to Frelimo. Much of this violence was instrumental and seemed to serve logistical purposes. Most analysts agree that Renamo’s indiscriminate violence could not be explained by indiscipline of lower rank and file (Gersony Reference Gersony1988; Hall Reference Hale1990; Seibert Reference Seibert, Abbink, de Bruijn and van Walraven2003). Without significant sanctuaries in neighboring countries, Renamo had to rely on the local population for resources such as food and labor (Hall Reference Hale1990, 52–53). In order to ensure the regular supply of new recruits and provide sufficient material resources to its troops, Renamo relied on violence for the purpose of intimidation. In my interviews, community residents usually referred to Renamo as “they,” implicitly including in the same category Renamo combatants, roving armed bands, and criminals that existed at the time. The use of a pronoun masks the identity and goals of a particular group, underlining the perception of the indiscriminate character of violence against civilians (Bertelsen Reference Bertelsen, Kapferer and Bertelsen2009, 219).

It is not entirely clear why Renamo shifted from more selective to more indiscriminate forms of violence, but it seems to be linked to the loss of popular support and the government’s counterinsurgent campaign. In the Maringué district in the central province of Sofala, for example, civilians became disenchanted with Renamo’s coercive style of rule in the late 1980s and withheld provisions from the combatants (Pereira Reference Pereira1999b, 49). Though Renamo formed governance structures, they usually remained rudimentary and provided few services. The loss of support, in turn, triggered coercive recruitment and terrorizing forms of violence such as mutilations in order to pressure civilians into obedience (Pereira Reference Pereira1999b, 49–50). The evolution of violence in Sofala appears to mirror the situation in Zambézia province. In Zambézia, violence against civilians rose when Calisto Meque took over Renamo’s northern command in 1986 (Robinson Reference Robinson2006, 265–66). Meque was a powerful and widely feared personality, known for his brutal treatment of the population. The rebels targeted civilians not only in Frelimo-held areas, but also in areas under their own control and enforced a coercive governance structure. Though Renamo had to accept certain setbacks as a consequence of Frelimo’s counterinsurgency campaign, the rebels ruled based on a system of fear in about 80 percent of the province until 1990 (Legrand Reference Legrand1993, 98).

While it is usually acknowledged that Renamo committed more violence against civilians than Frelimo, the government’s army also targeted civilians indiscriminately. The security and defense forces responded to Renamo’s 1986 offensive with a scorched-earth tactic to displace the population from Renamo-controlled territory (Legrand Reference Legrand1993, 95–96), which amounted to political cleansing (cf. Steele Reference Steele2017). The head of the newly created PCA was General Hama Thai, and General Lagos Lidimo was named Chief of Staff, “one of the most feared men in the army, having earned a reputation for ruthlessness and effectiveness as provincial commander in Zambézia in 1987–1988.”Footnote 22 Thus, Frelimo soldiers identified the PCA with strict discipline: all soldiers who defied orders and deserted were shot.Footnote 23

In sum, the Frelimo government was able to avert Renamo’s attempt to cut the country in half along the Zambezi River. However, Frelimo only regained control over the district towns; the countryside remained under Renamo influence and occupation. From there, rebels initiated frequent attacks on Frelimo strongholds. Such violent stalemates help community-initiated militias to form.

5.2 Civilian Responses and Naparama’s Formation

The Naparama militia emerged toward the end of Frelimo’s counteroffensive, presumably in late 1988. The population responded to the local military stalemates in various ways to protect itself and find a way out of the war, a process that culminated in forming the militia.

Zambézia’s population suffered severely from the consequences of war. Civilians were most vulnerable in contested areas, as a resident of a rural area in Nampula province explained: “We patrolled the bush, we stayed for two to three days [at a certain location] and then moved. We were afraid of both, the army and Renamo.”Footnote 24 In addition to the violence, the coastal areas of Nampula and the central areas of Zambézia were affected by famines in the late 1980s. Drought, poor harvest, and theft of relief goods by local officials, soldiers, and civilians led to hunger and mass starvation.Footnote 25 In early 1987, the situation in Zambézia was the worst in the country, with 105,000 people affected by hunger.Footnote 26

Though early on in the war the Frelimo government began to mobilize people to join popular militias and vigilante groups to help the war effort, civilians seem to have been rather passive victims in these early years. A resident of Nicoadala contrasted the involvement of the population in the war after the Naparama militia had emerged with people’s passivity before: “[When] the people came to experience the war [first-hand] and confronted the enemy, [the war] became a people’s war, whereas [before] when it was only Frelimo, the army confronted the enemy, and the people fled.”Footnote 27

In fact, before the Naparama militia formed, most people had responded to the violence by fleeing from their homes. At the time of Naparama’s emergence, 500,000 people in Zambézia province were displaced or affected by the war and 100,000 refugees had fled to neighboring Malawi.Footnote 28 The Frelimo government even actively encouraged displacement and sent civilian collaborators to Renamo-held areas to convince people to move to Frelimo-held areas. Many seemed to have resettled voluntarily into communal villages or centers for the displaced under government control. Local government reports from the Alto Molócuè district, for example, frequently refer to the mobilization efforts by militias and vigilantes in enemy areas and state the number of people who arrived in Frelimo-held zones.Footnote 29

However, the displaced in camps no longer had access to their fields and were dependent on limited relief aid supplies. That is why displacement often took on a temporary, and frequently a collective, character. Many respondents described to me how they left their village in the late afternoons: “[We] organized five to six families and went to sleep in the bush, in the morning [we] returned home. But courageous men got up during the night and [checked on] the house, since there were also others who came behind [Renamo] as bandits – not armed bandits – who broke into the houses.”Footnote 30 It was common for villagers to sleep and even cook in the surrounding areas of the village as long as the danger of attacks was high. This also shows that residents sought to stay close enough to their houses to keep an eye on their belongings and defend them against rebels and criminals.

Apart from displacement, civilians found different ways to protect themselves from the consequences of war, including various forms of what Arjona (Reference Arjona, Snyder, Moncada and Giraudy2019, 231) calls “cooperative” and “non-cooperative” behavior toward the armed group in control. Many civilians in Renamo-held areas cooperated with the rebels and abided by their rules, supported them with food, or even joined the rebels as combatants. But others, both in rebel- and in government-held areas, engaged in noncooperative behavior, such as informing the Frelimo authorities about rebel activity and conducting violent and nonviolent resistance against rebel rule and violence.Footnote 31 For example, when fleeing into the mountains in the Namarrói district, villagers developed elaborate techniques to defend themselves in their hideout and control the movement of people:

[W]e built a trap on the mountain. Many people arrived on the mountain through one single entrance. We placed stones by the entrance, and when the enemy was coming, we let the stones roll down [the mountain path], and this method let us save this area [from the enemy].Footnote 32

The pastor who told me this story explained that people were motivated to organize such resistance because they were “tired of being kidnapped, killed, and [their] property being burned; people began to search for ways to survive, and they asked themselves whether the war would [ever] end or not, as [they believed that] the people were the ones who would end it.” Community residents believed that they could not rely on the protection from the warring sides but had to organize their own forms of protection.

The most elaborate collective form of nonviolent resistance was peace zones, areas in which people were able to convince Renamo and Frelimo forces not to attack. These zones emerged in Zambézia with support from the Catholic Church and Jehovah’s Witnesses, and under the guidance of certain chiefs (Wilson Reference Wilson1992). However, peace zones provided limited relief from the hardship of being removed from one’s areas of origin. Peace zones were static and did not extend from one area to another. Thus, people were not protected in their home area, but had to move into such peace zones to be spared rebel violence.Footnote 33 Moreover, in the cases of the religious peace zones, membership was limited to those belonging to the religious community.

In contrast, those who violently resisted defended villagers in their home areas, which helped to maintain or even expand territorial control by the Mozambican government. Thus, the local and provincial administration (implicitly and explicitly) encouraged civilian violent resistance, and from the mid-1980s onward, society slowly militarized. In Marea, a locality in Namarrói district in Zambézia province, community residents used spears and machetes to defend those who had fled into the mountains.Footnote 34 A newspaper report from 1986 estimates that more than 10,000 civilians had armed themselves with spears and knives.Footnote 35 This development was not unique to Zambézia. In Nampula province, in the Nahipa locality of the Mecubúri district, the grupo decidido (the committed group), a group of civilians armed with spears and knives patrolling at night, emerged before the arrival of Naparama, mainly to respond to robberies and general lawlessness.Footnote 36 Everyone was called to defend their community, as this comment from a reader of a local magazine published by the Catholic Diocese in Nampula shows: “In my neighborhood, there is no mechanic, no professor, no one who is boss of any business. There is only one job: militiaman.”Footnote 37

What triggered communities to opt for violent forms of resistance? We should expect civilians to join and support the stronger side in search of protection (Kalyvas and Kocher Reference Kalyvas and Kocher2007). However, in this type of local military stalemate, there was no side that was clearly stronger than the other. In Renamo-held areas, logistical problems and the fact that the population served as a human shield for the rebels provided few benefits to those who did not have any political motivations to join or support the rebels. In Frelimo-held areas, the army’s inability to protect civilians against frequent Renamo attacks pointed to its weakness in dealing with the rebel threat. In the Alto Molócuè district, shortly before the Naparama militia emerged, “everything pointed to the fact that the government of Frelimo had lost control of the situation” (Pereira Reference Pereira1999a, 59). The violent nature of the stalemate required community residents to act. Villagers did not expect any effective response by the state, and thus sought to respond to the experience of the violence and loss of family members themselves. The leader of the above-mentioned grupo decidido in the Mecubúri district, for example, decided to organize the group in order to avenge his mother’s death at the hands of the rebels, a motivation that would also prove important for late joiners of the Naparama militia (see Chapter 7).Footnote 38 In that sense, we can speak of a community-empowering stalemate; its violent nature required and enabled civilians to act.

Violent resistance against rebel violence was not necessarily an expression of ideological support for Frelimo. The relevance of mechanisms such as revenge fits with Kalyvas’ (Reference Kalyvas2006, 97–101) expectation that the formation of (pro-government) militias does not necessarily need to be an expression of loyalty or ideological support for the government. In fact, both Zambézia and Nampula provinces have a long history of opposition to Frelimo due to the provinces’ historical marginalization and Frelimo’s failure to mobilize the population for the party’s cause (Legrand Reference Legrand1993, 88; Chichava Reference De Bruin2007; Do Rosário Reference Do Rosário2009). Thus, Renamo could exploit local grievances and benefit from higher levels of popular support by peasants in the north than in Mozambique’s south.

Several factors account for the “rebellious” character (Chichava Reference De Bruin2007) of Zambézia and strong opposition in Nampula. Frelimo’s party and state elite has been dominated by southerners; the independence movement’s penetration of both provinces during the liberation struggle was slow and ineffectual or – in the case of Nampula province – completely absent (cf. Legrand Reference Legrand1993, 88); and the peasant population opposed Frelimo’s policies after independence.Footnote 39 In Nampula, the construction of communal villages and the abolishment of traditional authorities sparked popular discontent (Geffray Reference Geffray1990). In Zambézia, it was the disrespect for traditional values more generally, which had been the basis for life in the province, that provoked opposition (O’Laughlin Reference O’Laughlin1992, 115; Ranger Reference Ranger1985, 189).Footnote 40

The Naparama militia built on the initial civilian responses to the military stalemate and the “tradition of rebellion,” but offered distinct offensive tactics, which increased the effectiveness of civilian protection and defense. The militia’s leader in Zambézia, Manuel António from the Namuno district of Mozambique’s northernmost province Cabo Delgado, was a charismatic young leader who claimed to possess special powers and to have received a calling to liberate the Mozambican people from the suffering of war. He was responsible for the formation of Naparama in a few districts in Nampula as well as districts across Zambézia.Footnote 41 The story he told community residents, journalists, and scholars was that he had died of measles as a child, had been buried, and then was resurrected after seven days (Nordstrom Reference Raleigh and Kishi1997, 58).Footnote 42 He maintained to have then spent six months in the mountains, where he received a divine mission from Jesus Christ and learned of a medicine to turn bullets into water.Footnote 43 António mobilized the first peasants in the Ribáuè district of Nampula province in late 1988 and then entered Zambézia in early 1989.Footnote 44 In Ribáuè district, António mobilized several men who then accompanied him on his travels as his personal guard.Footnote 45

The elaborate story of the birth of the movement was an attempt to legitimize António’s formation of an otherwise illegitimate armed group that could potentially challenge the Mozambican government. In the Makua-Lomwe culture that dominates the region in which António began to work, ancestral spirits live in cemeteries, the wilderness, rivers, and mountains (Lerma Martínez Reference Lerma Martínez2008, 207). António’s claimed stay in the cemetery and mountains was therefore significant for receiving magical powers from ancestral spirits.Footnote 46 In addition to building on traditional religion, the Naparama leader relied on references to Christianity, such as portraying himself as a messenger of Jesus Christ and using the bible in ceremonies. Combining traditional and Christian religion resonated within Zambézian communities for whom traditional leadership and religion and Catholicism were important cornerstones of their society.

The militia’s reliance on religious idioms fits well with a context in Mozambique in which the population develops severe grievances, but all political activity seems suspicious to the rulers (Machava Reference Machava2011; Bertelsen Reference Bertelsen2016). Margaret Hall (Reference Hale1990) suggests that leaders tend to rely on a religious framework to mobilize communities when a clear political ideology driving protest is lacking and political activity is suppressed. Across Africa, “inherently political peasant grievances have been channelled within a religious idiom. Traditional forms of belief particularly lend themselves to this form of protest, because of the usually strong association between the spiritual realm and the land” (Hall Reference Hale1990, 47–48). As Hall argues, this is how Renamo came to both support religious practice (within its own organization and within the communities it controlled) and reinstate traditional chiefs.

It is unsurprising, therefore, that the Naparama leader appealed to the beliefs and values important for the communities in which he was active.Footnote 47 The close link between Naparama to the communities was frequently expressed in my conversations with community residents and former Naparama combatants. Respondents stated that the primary task of the Naparama militia was to “defend the population.”Footnote 48 Former Naparama combatants claimed that they were the main – or even only – armed group that could successfully fight back Renamo and “save our sons, belongings, and family members.”Footnote 49 A former Naparama combatant confirmed, “we fought for the cause of the people.”Footnote 50

Community residents were enthusiastic about Naparama because the militia’s belief system resonated with them and the militia achieved concrete results for the local population. After years of displacement, Naparama allowed the displaced to finally return home.Footnote 51 António recruited young men living in impoverished refugee camps around government-controlled hamlets “with a promise of a means to restore their dignity” (Maier Reference Maier1998, 67). Most of the Naparama combatants in Nicoadala district, for example, came from among the displaced:

Where did Manuel António mobilize the people to initiate them into Naparama combatants?

That was in the village [for the displaced]. Because many refugees lived in the village – people tired of the war. So when [Manuel António] Naparama arrived and said he was bringing [this medicine], all of those who were in the village and suffered agreed [to participate], and the headquarters was there in the village.Footnote 52

Naparama’s major task was not to kill Renamo combatants and collaborators, but rather to capture them and their weapons and “recuperate” the population from Renamo-held areas:

We didn’t go [on missions] to kill. If a [Renamo combatant] was shooting over there and no more bullets were left in the magazine, we said “drop your weapon.” Really – you are here and he is where that mango tree is [demonstrating the proximity between himself and the Renamo combatant], [we said] “drop your weapon.” So he approached to fight with his bare hands – “let’s go, brother.” We, this movement, from the beginning to the end, it was all about recuperating [population]. It was not about killing. We recuperated people, even [when they were] armed. We captured weapons. Then we took the people [and the weapons] and presented them to the government.Footnote 53

The militia’s activities were largely successful. The British journalist Karl Maier estimated in February 1990 that Naparama had succeeded in returning over 100,000 displaced people to their homes.Footnote 54

In sum, Naparama provided a viable alternative to passivity for the community residents affected and displaced by the war, and a strategically effective response to the military stalemate. Communities were empowered as the warring sides could not make any significant military advances, leaving room for a third force to emerge to try and improve the odds of a government victory.

5.3 How Frelimo Came to Tolerate Naparama Activity

The success of forming the Naparama militia hinged on the government response to a potential third armed force. Frelimo’s reaction to the local military stalemates was twofold. First, the government focused on defending the status quo and its control over most district towns. Second, however, due to military and political weakness, its response became one of political and military inertia. Numerous reports written by local administrations and sent to the provincial headquarters of the directorate responsible to support local government at the time pointed to the dilemma in which local administrations found themselves. District towns received large numbers of displaced people that they sought to protect. However, the towns’ military capabilities were weak, as pointed out in several local government reports like the following describing the situation in Zambézia’s Lugela district in July 1988:

The defense and security forces in this district face lots of difficulties with the fulfillment of their missions, either due to the decrease in human resources or due to some of those responsible not fulfilling their responsibilities. As a consequence, the radius of our activities is limited to 5 km and it is most unfortunate that people are kidnapped from the district town without an adequate response from our side.Footnote 55

Lugela’s district administrator explicitly warned in his report that the stalemate could tip toward the rebels if the government would not provide an adequate level of security to the population. Although 5,000 people returned to government-held territory in June and July 1988, he feared that some would return to rebel-held zones because they were targets of violence in the government-held areas: “If we delay any further, the people will drink the politics of the enemy and it could be very difficult to recuperate [them].”Footnote 56 In fact, the report expressed concern that the population who used to live under Renamo control was politically indoctrinated, had gotten used to living under rules of banditry and had come to adopt an ethos of “not obeying anyone.” Speaking to the legitimacy of the administrator’s concerns, about two weeks after writing this report, Lugela’s district town was attacked and occupied by Renamo, lasting until December 1988.

Lugela district’s situation was one of the worst in the entire province, but it is exemplary of the pressure under which local administrators found themselves. Like Lugela’s district administrator, many administrators frequently requested military reinforcements for their districts, which they did not receive. Due to the limited number of troops available, Frelimo’s response was to create a “system of territorial security and defense,” which included the recruitment and training of village youths.

Given the strategy to involve the population in their own defense, Frelimo elites should have been highly enthusiastic about the newly formed Naparama as an auxiliary force. However, Frelimo’s official attitude was characterized by skepticism, for two main reasons. First, the roots of Naparama’s power went against Frelimo’s socialist stance against all things traditional (see Chapter 4). An official endorsement of Naparama or official collaboration with the militia would have contradicted the core of Frelimo’s ideology. Second, Frelimo was wary of Naparama’s true objectives during and potentially after the war. The government did not want to risk losing even more control over the war through outsourcing violence. Frelimo elites were concerned that a third armed force had emerged, which would, alongside Renamo, mount a challenge to the state. They did not trust Naparama sufficiently to grant them the agency needed to fight Renamo.

While the first reason was more of a concern for the provincial and national party leadership, the second reason was an immediate concern for the local administrations. Naparama initially formed without their knowledge, raising suspicions about their true objectives. In the first district of Naparama activity in Zambézia, Alto Molócuè, for example, António did not introduce himself to the local administrator when he arrived in the district town (Pereira Reference Pereira1999a, 83). Similarly, in Nampula province, the Naparama unit in the Murrupula district formed without the knowledge of the local administration. What happened subsequently in Murrupula shows how suspicious Frelimo was of the militia. When Murrupula’s district administrator learned about the new armed group, he contacted the party provincial headquarters in Nampula city for advice.Footnote 57 The provincial governor asked the “department of ideological work” to conduct a study and they sent a delegation of party officials to meet with the Naparama leadership in Murrupula. As the head of the delegation explained to me, the Frelimo leadership feared that the war in Mozambique could intensify in the same way as it had in Angola if it allowed a third armed group to operate:

The government was concerned that, similar to Angola where there was the MPLA, the movement of Holden Roberto and the movement of Savimbi, the same thing would happen here and there would be three movements, Frelimo, Renamo and Naparama struggling for power. …

I went [to Murrupula] because we in the government thought that Naparama was a movement that would seek to govern after the war. We found that Naparama only sought to end the war. They were volunteers and didn’t not have any political program.Footnote 58

The investigation into Naparama in the Murrupula district thus concluded that Naparama would not pose a threat to Frelimo, whether over the short or the long term.

Thus, the party’s hesitance to rely on the support of the community-initiated militia soon gave way to pragmatic considerations. Local state and military officials realized the value of Naparama’s contribution to stability in the short term. In many districts, local officials actively supported the mobilization of youths for militias like Naparama. This created a window of opportunity, which helped form Naparama units in various districts. Local administrations realized that if they wanted civilians to support the war effort, they had to tolerate groups like Naparama. As a provincial government representative told me,

When the government asked for the population to defend itself, it did not foresee the Naparama, a group well organized. Samora MachelFootnote 59 said that Naparama [militias] are bandits and thieves. However, during the colonial period, the Portuguese called Frelimo “turas” [disobedient people; rebels], but they were well organized.Footnote 60

So even though Frelimo was tempted to label Naparama “thieves” to delegitimize them, local government officials were forced to take the militia seriously. Being too weak to defeat Renamo on its own, Frelimo had no choice but to tolerate Naparama. One district administrator pointed out that “all of us were preoccupied with how the war could be stopped.”Footnote 61 Another local government representative expressed how helpless the local government was:

Were you worried that Naparama would create a group that would fight against Frelimo?

The war was really bad, so what could we have done?Footnote 62

Thus, as a community leader conveyed, “the government didn’t see any alternative to accepting [António’s offer] to do the work that he sought to do.”Footnote 63

While Frelimo’s most common strategy was to tolerate Naparama activity, it sometimes even actively collaborated with the militia. In some instances, Frelimo representatives encouraged local leaders to mobilize youths for Naparama and supported the militia with weapons and supplies. Naparama’s successes on the battlefield dispelled Frelimo’s initial concerns:

After [Naparama] defeated [Renamo], Frelimo assisted them in the collection of war material – there was support, yes, because Naparama went in front [and the army behind them]. Frelimo didn’t like Naparama, but after they had seen the work that Naparama was doing, they liked them.Footnote 64

Thus, the governors of both provinces, Zambézia and Nampula, supported local administrations collaborating with Naparama. Nampula’s governor signed a document supporting the work of Naparama in Murrupula.Footnote 65 Frelimo encouraged the local party and provincial leadership to develop ways to integrate Naparama into the local security apparatus.Footnote 66 In Zambézia as well, the provincial governor “recommended to work with António. We had to welcome him and tell him that he could work in our districts. However, he was not part of the military, he was a civilian.”Footnote 67

In emphasizing the “civilian” role of António and Naparama, Frelimo sought to control the militia’s activities and ambitions. The district administrators’ overall attitude was “to give [Naparama] space, but also to control them.”Footnote 68 Government representatives reiterated that Naparama was a force of the people and that militia members were volunteers.Footnote 69 In addition to denying Naparama any political or military character by labeling Naparama members “civilians,” Frelimo avoided recognizing – and paying – Naparama as an official auxiliary force. Also, the government maintained that it could not be held accountable for offenses perpetrated by Naparama.Footnote 70

Naparama worked hard to win the trust of the local administrations. Naparama leader António repeatedly highlighted his nonpolitical objectives – for the time of the war and after. His response to the question about his ambitions was always that his only goal was to liberate the Mozambican people.Footnote 71 He stated that he did not seek political power and was a loyal Frelimo supporter:

When the war ends, the battle ends. I will plow a field, I will live. They say [about me] that I want to form a party. How?! With what money? … My father is Frelimo, my mother is Frelimo, I am Frelimo!Footnote 72

To counter the government and the army’s suspicion, the Naparama units in both Nampula and Zambézia provinces presented themselves as civilians tired of the war who had formed a group that would not challenge the government: “When the government asked, [Naparama] said, ‘We are tired of the war. We don’t want to stage a protest or anything like that. We want the war to stop.’”Footnote 73

When confronted with the provincial government’s investigative delegation, Naparama members in Murrupula insisted that they were civilians whose objectives were merely defensive, not political. Recalling the delegation’s visit, Murrupula’s Naparama leaders told me that

We met [the members of the provincial government delegation] and we told them that we were civilians, that we were tired [of the war], and that we were not [militarily] trained. We lost many of our belongings, and that’s why we prepared ourselves to go and search for our belongings in the bush. … They asked us whether we wanted to be paid, but we told them that we didn’t have a mandate; we had our drugs only to defend ourselves.Footnote 74

Naparama combatants in Nicoadala in Zambézia province emphasized that there was no contradiction between Naparama’s and Frelimo’s goals and that both had the same enemy:

The Naparamas are Mozambican, Frelimo is Mozambican. Renamo knows that [Frelimo] fought for Mozambique and that is why [Frelimo] is [ruling], but [Renamo] does not want [that]. Everyone is joining Frelimo in their sorrow. [Renamo] doesn’t want [it].Footnote 75

A journalist who had met António concluded that Naparama did not have political ambitions, but sought to help the people:

They said they neither belonged to Frelimo nor Renamo. They were independent. They did not have political aims, but social aims – to liberate the people. Renamo included many people who were not convinced [by the group’s aims], so the aim was to liberate these people.Footnote 76

In sum, Frelimo had significant concerns about the newly formed Naparama. Nevertheless, the challenges the state faced during the war against Renamo forced the Frelimo leadership to tolerate and even actively encourage local administrations to mobilize Naparama units in Zambézia and Nampula provinces. The need for additional defensive capacity and the helplessness of the local administrations created a window of opportunity for Naparama to form.

5.4 Conclusion

Naparama formed because of the distinct dynamics of war in Zambézia and Nampula provinces. Military stalemates on the local level encouraged communities to form militias. This strategic situation shaped community incentives to form armed groups rather than flee or rely on Frelimo’s army to protect them from insurgent violence. The stalemate also shaped Frelimo’s incentives to tolerate militia activity. Naparama’s offensive tactics promised a more effective response to the threat posed by Renamo. Frelimo’s changing attitude toward traditional forms of power facilitated the formation of the Naparama militia, as it created a window of opportunity for an additional armed group to fight the insurgents.

This implies that had the military situation been more beneficial for Frelimo, the population and the local state and military elites would not have had to rely on an auxiliary force. At the same time, had Frelimo been losing and its areas of control been taken over by Renamo then the formation of a militia would not have been possible – at least not a militia inclined to support the incumbent. Some level of control over territory and population is necessary to form militias that work alongside the incumbent.

Having defined the conditions under which civilians take the initiative to form militias, I will now turn to an aspect that distinguished the Naparama militia from the other civilian initiatives that responded to the war: its rapid diffusion from one district to another.