Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part 1 Works

- Part 2 Impact

- Part 3 Approaches

- 9 King's Contestatory Intertextualities: Sacred and Secular, Western and Indigenous

- 10 Thomas King's Humorous Traps

- 11 “Have I Got Stories—” and “Coyote Was There”: Thomas King's Use of Trickster Figures and the Transformation of Traditional Materials

- 12 “One Good Story”: Storytelling and Orality in Thomas King's Work

- 13 Maps, Borders, and Cultural Citizenship: Cartographic Negotiations in Thomas King's Work

- 14 One Good Protest: Thomas King, Indian Policy, and American Indian Activism

- 15 “Sometimes It Works and Sometimes It Doesn't”: Gender Blending and the Limits of Border Crossing in Green Grass, Running Water and Truth & Bright Water

- Part 4 Encounters

- Part 5 Thomas King—A Bibliography

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

10 - Thomas King's Humorous Traps

from Part 3 - Approaches

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2013

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part 1 Works

- Part 2 Impact

- Part 3 Approaches

- 9 King's Contestatory Intertextualities: Sacred and Secular, Western and Indigenous

- 10 Thomas King's Humorous Traps

- 11 “Have I Got Stories—” and “Coyote Was There”: Thomas King's Use of Trickster Figures and the Transformation of Traditional Materials

- 12 “One Good Story”: Storytelling and Orality in Thomas King's Work

- 13 Maps, Borders, and Cultural Citizenship: Cartographic Negotiations in Thomas King's Work

- 14 One Good Protest: Thomas King, Indian Policy, and American Indian Activism

- 15 “Sometimes It Works and Sometimes It Doesn't”: Gender Blending and the Limits of Border Crossing in Green Grass, Running Water and Truth & Bright Water

- Part 4 Encounters

- Part 5 Thomas King—A Bibliography

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

Summary

While Wenabozho was walking along the lakeshore he met up with a fellow Indian. He asked him, “Wenabozho, I want to ask you something. How is it that you're so smart?” Wenabozho answered him, “Look here, I always eat smartberries.” …

Wenabozho collected those rabbit turds and handed them to his companion. The one going around being taught took them and popped them in his mouth. But then he said, “Ew! Those are rabbit turds! Those aren't smartberries!” Wenabozho replied, “Yes, you're right. Those aren't smartberries. Now you are smart, too.”

David Treuer translates this Wenabozho story by Rose Foss, an elder from the Mille Lacs reservation, to demonstrate a disconnect between Ojibwe oral tradition and the postmodern sensibilities of Louise Erdrich's novel Love Medicine (Treuer 2005, 31–32). For Treuer, this Wenabozho story moreover allegorizes the quest for “authentic Indigenous culture” that so often impels readers, critics, and even authors in the field of Indigenous literature. Smartberries—discrete, displaced packets of cultural knowledge—are but signs of the literature's desire for a holistic, tribally specific cultural understanding, and should not be mistaken for an end in themselves.

There is a reciprocal irony in the fact that Treuer uses a trickster tale to illustrate the dangers of eating smartberries, since the trickster could be characterized as the smartberry par excellence. The tremendous literary success of Gerald Vizenor and Thomas King, both writing as self-declared trickster-authors, has done much to install a poststructuralist, pan-Indian species of this culture hero as a dominant literary and critical trope, what Kristina Fagan calls “a stable symbol of chaos, disorder, and resistance” (2010, 5).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

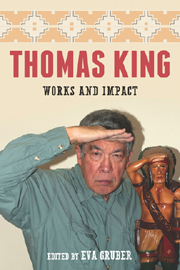

- Thomas KingWorks and Impact, pp. 167 - 183Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2012