Introduction

We have all heard the old saying ‘practice makes perfect’. Perhaps, for some of us, the images evoked by this expression are rather dreary ones, maybe from childhood, of trying to perfect some skill that we had little interest in learning. On the other hand, others of us may think positively of the rewards that came our way as a result of devoting time to practise something that we enjoyed doing.

In this chapter, we consider the place that practice might have in the language classroom. We will address these three questions:

Why practise?

How to practise?

How much practice?

When we talk about practice in language learning, we need to remember that practice can and should involve any and all of the language skills. We can practise improving our receptive language skills, for example, by listening to songs or by reading magazines in the language we are learning. In this chapter, however, we are mainly concerned with practice as it refers to the use of oral productive language. One reason for this is that, while it may be possible to set up opportunities for students to practise other language skills outside of the classroom (we have referred to ways that this might happen in other chapters), it is often difficult to arrange ways for students to practise speaking and interacting in a foreign language outside of the language classroom. In fact, the lack of opportunities for students to practise and use the language they are learning has been identified as the key characteristic that distinguishes the foreign language classroom from the second language classroom (Reference Ortega and DeKeyserOrtega, 2007). The challenge for the language teacher, then, is how, in the classroom, to compensate for this lack of opportunities.

Why Practise?

To answer our first question as to why practice might be useful in the language classroom, we need to understand something of skill acquisition theory (Reference Carlson and NadelCarlson, 2003), first used within the area of cognitive psychology to explain general learning processes.

Skill Acquisition Theory

Skill acquisition theory explains how learners might proceed from basic to more advanced proficiency in a given skill. Reference DeKeyser, Doughty and WilliamsDeKeyser (1998, Reference DeKeyser and DeKeyser2007) has found this theory useful to explain how language learners, over time and with practice, become more proficient until eventually they may be able to produce language without thinking explicitly about the language they are using.

Factual knowledge that a learner might have about a language.

This theory helps us understand why repetitive practice of a skill helps develop mastery. It is fundamental to many of the abilities we develop, from learning to eat, tying a shoelace, learning to read and write, playing an instrument, learning to play a sport, riding a bicycle, and driving a car. Our early attempts are clumsy and full of errors, but we can achieve a measure of mastery through trying over and over again. The same applies to language learning. Classroom language learners often first depend on ‘declarative knowledge’ when something is new to them (see Figure 6.1 for a summary of the processes of skill acquisition theory). That is, they depend on information but are unable to make use of that knowledge yet. For example, they might have information about, and even be able to explain, how past action is expressed in a particular language, but they are not able to use this knowledge to communicate about past action. Through practice, however, they will develop ‘procedural knowledge’ and this type of knowledge will manifest itself in language behaviour, so that, using the previous example, they will now be able to use verbs in the target language to communicate about events in past time. At first, using this procedural knowledge might take up quite a lot of their attentional resources, so that they will need to be very focused on the new language that they are using. They probably won’t have the capacity to be aware of much else. They will probably also be slow at using the new language and liable to make errors.

Figure 6.1 The processes of skill acquisition theory

Procedural Knowledge

Knowledge of how to use language without having to think explicitly about it.

Here is an example of this in action from a high school French class. The students are learning to use negation, or how to say that they don’t or didn’t do something. Here they practise by reporting what they ‘did not do’ on the weekend. The teacher gives a model, and explicitly directs them to use ‘ne … pas’ around the verb. However, this requires some trial and error. Notice how much the teacher corrects and guides them at this stage (the sections of the text that are examples of negation or attempts at negation in French are underlined).

Example 6.1

Translation Comment T I want to know what you did not do on the weekend. D’accord? Remember last week on a discuté the passé composé, the negative dans le passé composé. Moi, moi, je n’ai pas fait mes devoirs pendant le weekend. Je n’ai pas fait mes devoirs. Qu’est-ce que vous n’avez pas fait ? What did you not do? So putting in ‘ne pas’ in the passé composé. [Names a student] … ok? Remember last week we talked about the passé composé, the negative in the passé composé. I, I did not do my homework during the weekend. I did not do my homework. What didn’t you do […] S Umm, je n’ai regardé pas la télé Umm, I did watch not TV The student uses the negative but not completely correctly T Ok. Where does ‘ne pas’ go in the passé composé negative? Around which part? You said it all the right way except one S Je n’ai I did T Right, you said ‘Je n’ai regardé pas’ … Right, you said ‘I did watch not’ … The teacher repeats what the student said previously so that they can hear their mistake S Je n’ai pas regardé [la télé] I did not watch [TV] The student uses the negative correctly T Je n’ai pas regardé [la télé]. C’est ҫa I did not watch [TV]. That’s right (Data adapted from Reference TogniniTognini, 2008, p. 161)

These students have to consciously think about where to put the ‘ne pas’ to indicate negation. As we continue to practise, however, our procedural knowledge can become ‘automatised’ (Reference DeKeyser and DeKeyserDeKeyser, 2007). With automatisation, our use of the new language will be spontaneous, effortless, fast, and without error. DeKeyser explains that the word ‘automatisation’ can be used narrowly to mean the speeding up of performance at a task (as in developing fluency) or more widely, as it is understood here, to refer also to the restructuring of knowledge that happens as learners become more proficient. For the language teacher it is important to understand that all these processes of skill acquisition theory require a considerable amount of practice and take place over time.

There is, however, another very compelling reason for incorporating opportunities for practice in the language classroom. Reference Ortega and DeKeyserOrtega (2007) claims that the right type of practice, where there are opportunities for learners to use the language to communicate, can help learners notice aspects of language, and even reflect on and test out these aspects of language. This noticing, reflecting, and experimenting with language can promote language learning and contribute to the development of declarative knowledge. In other words, there could be times when practice could also act as a catalyst at the beginning of the sequence to set in motion the processes in Figure 6.1, alongside its more fundamental and crucial role in helping advance language learning processes along the sequence. For example, in the classroom we describe below, Amelia is asked the question ‘What don’t you like doing?’ (‘Qu’est-ce que tu n’aimes pas faire?’) and realises that she doesn’t know how to say ‘do athletics’ in French. This realisation is the catalyst for her to seek help from the teacher, who tells her that it is ‘faire de l’athletisme’, and who helps her construct the sentence she wants to say. Three days later, when we interview her, Amelia uses this expression, demonstrating that she is at least partway along the process of learning it (though we can’t be sure whether she has learnt it well enough to be able to use it spontaneously in a conversation).

The examples of practice that we will look at in this chapter come from Jessica’s classroom of Year 9 students of French who are towards the end of their first year of learning the language. The context is that they are practising for an oral

language assessment,

the following week. Notice how, in an interview, when asked about her goals

for the lesson, Jessica refers to both the idea of increasing fluency and

also the possibility that practice may lead to new learning for her students; she suggests that her students will be noticing what they don’t know and asking questions.

How to Practise?

In recent times, getting students to practise may have become rather ‘out of vogue’ in some language teaching contexts. This is often a reaction to the type of meaningless drills and exercises that were characteristic of an audio-lingual approach to language teaching (Reference Larsen-Freeman and AndersonLarsen-Freeman & Anderson, 2011). ‘Drills’ have been ‘alternately advocated, demonised, derided and resuscitated’ (Reference DeKeyser and DeKeyserDeKeyser, 2007, p. 10). Reference DeKeyser and DeKeyserDeKeyser (2007) describes three types of drills: (1) mechanical, (2) meaningful, and (3) communicative. He makes a case for almost, but not quite completely, discarding type (1) and for incorporating the other two inside the classroom. This brings us, of course, to the second question of the types of practice that might be helpful, and not so helpful, in the language classroom.

1 Mechanical Drills

Reference Paulston and BruderPaulson and Bruder (1976, p. 3) describe mechanical drills as involving ‘complete control of the response and only one correct way of responding’. Reference DeKeyser, Doughty and WilliamsDeKeyser (1998, p. 53) goes on to explain that in mechanical drills, learners are only practising ‘language-like behaviour’ and ‘shuffling forms around’ rather than conveying meaning. The problem with drills is that it is possible to carry them out without understanding what is being said at all. This type of practice was very common in the audio-lingual classroom and has been criticised for not helping learners learn to use language in communication.

For proceduralisation, and therefore learning, to occur, language forms need to be associated with meaning. In this way, form-meaning links or mappings are built up in long-term memory (we discussed the importance of these in Chapter 5). For example, when a learner of English realises that when someone says they are ‘going to do something’ (form), they are talking about a future intention (meaning), they have made a form-meaning mapping. As we have already mentioned, drills can be carried out without understanding the language being used at all, and so don’t help these form-meaning mappings to be established.

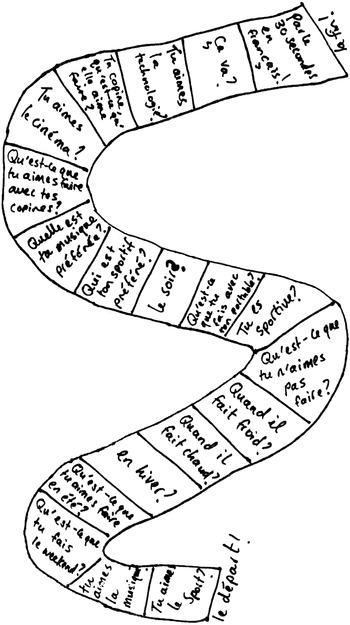

However, Reference DeKeyser and DeKeyserDeKeyser (2007) doesn’t go as far as saying that there is NO place for mechanical drills inside the classroom. He mentions that drills can be helpful for some learning, for example, pronunciation and verb forms. Reference HarmerHarmer (2012) also explains that drills help students ‘to get used to new language’ (p. 109). In discussing opportunities for ‘language-focused learning’ in the classroom, Reference NationNation (2007) talks about the importance of including ‘pronunciation practice, using substitution tables and drills [and] learning vocabulary from word cards’ (p. 6) in the classroom. An example from Jessica’s classroom is when Rosie and her game partners are busy playing the snake game (see Figure 6.2). In Example 6.2, Ruby and Chanelle focus on the question ‘Qu’est-ce que tu aimes faire en hiver?’ (‘What do you like doing in winter?’). However, Rosie has noticed the form ‘en été’ (‘in summer’) from the preceding question ‘Qu’est-ce que tu aimes faire en été?’ (‘What do you like doing in summer?’) and she has decided to ‘take time out’ to repeat ‘en été’ to herself. In this way she can practise the pronunciation of this expression, which presumably is one that is new to her.

Figure 6.2 The ‘snake game’

Example 6.2

Of course, here Rosie takes the initiative to do this on her own, but the teacher could also have had the whole class practise their pronunciation of this and similar phrases. What the teacher, Jessica, did do during the lesson was to stop the whole class so that they could recite together the conjugation of the verb ‘être’ (je suis, tu es, etc.) to the tune of ‘The Pink Panther’.

In an interview Jessica talks further about the type of mechanical drills that she has her students work on in the classroom and how useful they are for teaching verb conjugations. She explains how for ‘-er’ verbs she teaches a ‘little rhyme; “e, es, e, ons, ez, ent” you know for the endings’ and how her students respond positively ‘they absolutely loved the “e, es, e, ons, ez, ent”’ and said “we want more of that”’. She also describes a song (a round), to the tune of ‘Frère Jacques’, that she uses for teaching the conjugation of ‘avoir’ (to have):

| j’ai tu as, j’ai tu as, |

| il/elle a, il/elle a, |

| nous avons vous avez, |

| nous avons vous avez, |

| ils/elles ont, ils/elles ont. |

Such short drills and songs can help learners retain formulaic knowledge and explicit (declarative) knowledge that they can draw on in production. But, where input and opportunity for communicative use is limited, the danger is that students become dependent on this declarative knowledge and never progress beyond it.

2 Meaningful Practice

We argue, as Reference DeKeyser and DeKeyserDeKeyser (2007) and others note, that mechanical drills are of limited benefit in the language classroom. They can be useful as an early aid to memory, as we have seen in the previous section. They can also be helpful for aspects of the language which are less noticeable, or which are less meaningful, and so, therefore, are harder for learners to pick up. In foreign language contexts where input and time are limited, however, Reference DeKeyser and DeKeyserDeKeyser (2007) argues strongly in favour of the inclusion of meaningful and communicative drills. This is because the latter allow learners to make connections between a language form and its meaning and, therefore, do allow for the process of proceduralisation. In this chapter we are going to refer rather to meaningful and communicative ‘practice’, because we consider that the term ‘drill’ does little to describe the way that language is used in these types of practice. Meaningful practice can be understood as practice that a student cannot complete without understanding what is being said (Reference Paulston and BruderPaulston & Bruder, 1976).

Jessica had her twenty-seven Year 9 students work at meaningful practice as they prepared for an oral assessment. We have had glimpses into Jessica’s classroom elsewhere in this book; Jessica teaches in a single-sex, state-run girls’ school. Her students have three fifty-minute lessons a week throughout the year. In Year 11 they will sit a national exam, the National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA). One of the components of NCEA, the ‘Interact Standard’, requires students to ‘interact using spoken French to communicate personal information, ideas and opinions in different situations’ (www.nzqa.govt.nz). Jessica’s school decided that at the end of Year 9, their first year of learning French, all students would have the opportunity to take part in a mock ‘Interact Standard’.

Jessica gives some information about how her students will be assessed as they interact in pairs.

To prepare for this assessment Jessica devised a game (see Figure 6.2; see also an English version of the game in the Appendix). It was played with a dice and counters, and as students landed on the different sections of the snake shape, they had to answer specific questions. An answer in French meant they could advance, a response in English meant they had to go backwards. The language that Jessica chose to include in the game was language that the students had already been introduced to. This is an important point.

Reference NationNation (2007) claims that in developing fluency,

the language that students work with should be largely familiar to them. In an interview, Jessica describes the language work (we highlight the target language and include translations) that predated the practice described in this chapter. This was, firstly, a unit that the students had previously completed and, secondly, a poster they had written about themselves using the language of the unit.

In this chapter we describe the lesson that Jessica taught to allow her students to consolidate and revise this language work, described above.

Jessica allowed students to work in groups of approximately three as they played the game. They were able to choose which groups they worked in (something that adolescents say is important to them, see Chapter 2). When students had completed the game, they were given the choice of either playing it again outside in the corridor or doing some writing. They were told that, in the writing, they should develop their ideas based on the language they had practiced.

That this type of practice was meaningful is evident from the fact that the students had to understand what each question was asking and then find the French to construct an answer that was an appropriate response. We can see in Example 6.2 that Ruby has actually translated the question ‘Qu’est-ce que tu aimes faire en hiver?’ Perhaps the fact that she has done this indicates that she and/or Chanelle were not entirely familiar with the language of the question and needed the English to help her/them. Chanelle has responded appropriately by saying she watches television (‘En hiver je regarder la télé’), albeit without conjugating the verb ‘regarder’, to watch.

We can hypothesise that the kind of meaningful practice provided by this game presented students with opportunities for language proceduralisation, as seen in Example 6.2, and automatisation, as seen in Example 6.3. In Example 6.3, the two students, Hannah and Francesca, appear more at ease with the meaning of the question forms and with answering them. This may be because they are playing this game for a fourth time, at this stage of the lesson. These students elected for a second practice in the corridor outside of the classroom, rather than doing written work inside, and during each of the two practice sessions that the teacher made time for in this lesson, they played the game twice.

Example 6.3

Hannah Tu es sportive? Are you sporty? Francesca Oui, je suis assez sportive. Yes, I am fairly sporty. Hannah Qu’est-ce que tu fais avec ton portable? How do you use your mobile? Francesca Avec mon portable je chat sur facebook.Qu’est-ce que tu fais avec ton portable? I use my mobile to chat on Facebook. How do you use your mobile? Hannah Avec mon portable j’envoie des SMS et les emails. I send texts and emails with my mobile.

The increased practice that these two students had may have served to develop automatisation, resulting in an improvement in language fluency. This is suggested by Hannah and Francesca’s responses to a written questionnaire filled out at the end of the lesson. When asked what they thought they had learnt in the lesson, Hannah noted ‘coming up with answers on the spot’ and Francesca ‘answering questions on the spot’.

3 Communicative Practice

Is Jessica’s game an example of communicative practice as well as meaningful practice?

To answer this question, we need to establish what is meant by communicative practice. In communicative practice activities, the actual exchange of information is the goal of the communication and the information that is exchanged is something that the listener (or reader) does not already know (Reference DeKeyser and DeKeyserDeKeyser, 2007). In other words, there has to be some sort of communicative gap that is bridged as the practice takes place. It is hard to be sure if there was a gap for Jessica’s students and whether, as they played this snake game, they were learning something new about their conversation partners. They may have already had a reasonable amount of knowledge about their classmates and there may have been little that was new for them to find out (especially as students self-selected their partners and tended to interact with their friends). This exchange of new information or ‘gap’ is important because it motivates learners to pay attention to each other as they communicate. Listening to each other is also important for learning; it is an opportunity for learners to be exposed to language input (as we saw in Chapter 3).

One simple way that this game could be made into communicative practice is to tell the students that, as they played the game, they had to tell one lie and that their partner had to correctly specify, at the end of the game, what that lie was. That would ensure that students attended to each other’s answers and that there was a focus on the information being exchanged.

Ortega’s Optimal Practice

We have already referred to Reference Ortega and DeKeyserOrtega’s (2007) claim that practice has the potential to drive language learning, to act as a catalyst for acquisition. In a chapter that deals with practice in the foreign language classroom, she argues that optimal practice needs to respect three principles (Reference Ortega and DeKeyserOrtega, 2007, pp. 182–186). These are:

1 Language practice needs to be interactive.

2 Practice needs to be meaningful.

3 There should be a focus on task-essential forms.

We will discuss each of these in turn and look at how they might be facilitated in the classroom with examples from Jessica’s lessons.

The First Principle Is that Language Practice Needs to Be Interactive

Fortunately, it may be relatively easy to facilitate ‘interactive practice’ in the language classroom where adolescents are the learners, for two main reasons. Firstly, the adolescent language learner prefers cooperative learning over teacher-fronted learning; this means that learners are more likely to be attending to language in exchanges initiated by peers than those initiated by the teacher (Reference WilliamsWilliams, 1999). Secondly, relationships with peers are very important, as we saw in Chapter 1.

There are several reasons why language practice needs to be interactive, the most obvious being that there are far more opportunities for learners to use language when they are interacting in pairs or groups than when the teacher is directing the interactions. Another reason why interactive language practice is important is that, during practice, learners have opportunities to negotiate for meaning, to identify problems and to seek solutions. We will look at these in Examples 6.4 and 6.5 from Jessica’s classroom where we argue that, through the interactions that took place as the students worked in groups of three, students could have had opportunities to expand their language competence.

Example 6.4 Playing the game in Figure 6.2, Ruby throws a five on the dice and together with Rosie counts up to five in French. Ruby’s counter lands on the question – ‘qu’est-ce que tu aimes faire en hiver?’ (what do you like doing in winter?)

It is obvious from the rising intonation Ruby uses at the beginning of this interaction that she was not sure that her message was clear. However, through the interaction that follows she receives positive feedback that she had communicated what she intended. Both students paid attention to the meaning of what was said.

In Example 6.5 Amelia realises that she does not know or remember the word for Saturday in French. Her conversation partner provides it for her.

Example 6.5

Amelia Quand il pleut je télécharge le musique et en hiver j’aime faire de la natation … le weekend le weekend; comment dit-on Saturday When it rains I download music and in winter I like swimming … at the weekend at the weekend; how do you say Saturday S samedi Amelia Samedi, le samedi quand il chaud mais dimanche quand il pleut quand il fait pleut Saturday on Saturday when it hot but Sunday when it rains when it makes rains

Three days later Amelia was able to give the correct word for Saturday in French; this is some evidence that this exchange during language practice had led to vocabulary development for Amelia.

Having a classroom environment where students are able to work together collaboratively, as they do in these examples, is something that is unlikely to happen by chance (see Chapter 1). The teacher may need to train students to work together in ways so that they are able to encourage and support their peers and give them the type of feedback that will promote learning (Reference Philp, Sato and BallingerPhilp, 2016; Reference Sato and BallingerSato & Bollinger, 2012). Building an environment where the relationships are positive and where there is a high degree of trust may take time. At the same time, as students work together in these ways, it will be important that the teacher monitors group work and provides support and scaffolding as necessary (Reference Philp, Adams and IwashitaPhilp et al., 2013).

The Second Principle Is that Practice Needs to Be Meaningful

Reference Ortega and DeKeyserOrtega’s (2007) principle that practice needs to be meaningful reinforces DeKeyser’s claim that only meaningful or communicative practice can help learners ‘proceduralise’ knowledge so that it is available for use. Ortega argues, as we have already discussed, that meaningful practice may do more than facilitate proceduralisation, it can be ‘competence-expanding’, that is, it can act as a catalyst for new language learning. For example, she claims that learners may have the opportunity to realise that they need language that they do not have and may ask for help from a teacher or from a peer (we have an example of the latter in Example 6.5). Example 6.6 is an example of a student asking the teacher for a word they do not know and then using this word in a sentence, pushing their language (see Chapter 4) output to attempt a grammatical structure that they haven’t yet mastered (note that we have already explained in the ‘Meaningful Practice’ section how the game that the learners in Jessica’s classroom played required a focus on meaning).

Example 6.6

Translation Explanation Ruby Quelle est ta musique préférée? What is your favourite music? Rosie Mon musique préférée c’est Lorde My favourite music is Lorde Chanelle I don’t like her Ruby (or Rosie?) Pourquoi … pourquoi Why … why It is not possible to determine exactly who asks Chanelle why she doesn’t like Lorde Chanelle Parce que c’est weird oh Madame Because it is weird oh Madame Chanelle doesn’t know the word for weird in French Chanelle Madame comment dit-on weird? Madame how do you say weird? She asks the teacher T Bizarre. Bizarre The teacher gives her the French word for weird Chanelle C’est biz parce que elle c’est bizarre It’s wei because she it’s weird She tries using this in a sentence but makes a mistake T Elle est bizarre She is weird The teacher says it correctly (recasts it) Chanelle Elle est bizarre She is weird Chanelle repeats it T Ta copine, elle est bizarre Your friend is weird The teacher thinks Chanelle is talking about her friend Chanelle Non, ah Lorde No, ah Lorde Chanelle corrects her T Oh Lorde est bizarre. Elle est bizarre. Oh Lorde is weird. She is weird. Chanelle Elle est bizarre She is weird Chanelle correctly repeats again the sentence she had difficulty with before T Elle est un peu bizarre, je suis d’accord. She is a bit weird, I agree

Example 6.6 is part of the same conversation as Example 6.4, a little further on in the practice activity and this time Chanelle joins the interaction along with Ruby and Rosie. This is an instance where the students are focused on really communicating a message (we could say that at this point the students ‘step outside’ the meaningful practice activity, so to speak, and that it becomes an actual conversation) as either Ruby or Rosie (not possible to distinguish exactly who from the recording) asks Chanelle why she does not like Lorde. Chanelle needs the word for ‘weird’ in French and so asks for assistance from the teacher. That this exchange was competence-expanding and led to new language learning for Chanelle is attested by the fact that three days later she was able to say what the word for ‘weird’ was in French and was also able to demonstrate that she could correct ‘parce qu’elle c’est bizarre’ to ‘parce que c’est bizarre’.

The examples given here come from a unit of work taught over three lessons. Examples 6.7 and 6.8 come from the lesson following the one (on a Monday) that has so far been described. This next lesson, on a Wednesday, also had the aim of giving learners practice in using language they were already familiar with. As Jessica says in the interview:

In Wednesday’s lesson she gave each student a whiteboard and asked them to write

as many questions as they could remember. She then asked them to find someone and ask them the questions on their whiteboard. A little later in the lesson she asked students to find someone new and ask their questions again. Many of the questions that the students wrote were similar to the ones they had worked with during the game the previous day. In Example 6.7, as Rosie formulates her answer, she has the opportunity to notice a ‘hole’ or gap

in her own language competence (see Chapter 4).

Example 6.7

Translation Explanation Rosie En hiver hiver je joue le hockey non je joue au hockey or is it le hockey … mmm tout le tout tout le temps all the time In winter winter I play the hockey no I play hockey or is it the hockey … mmm all the all all the time Rosie realises that she doesn’t know whether she should say ‘jouer le hockey’ or ‘jouer au hockey’ Chanelle Et en hiver je joue au underwater hockey tous les jours And in winter I play underwater hockey every day Chanelle does not directly answer Rosie’s musings, but she uses the correct form herself in talking about what she likes doing in winter (je joue au underwater hockey).

Chanelle uses the correct form for the structure that Rosie is not sure about. We do not have the data to know whether Rosie noticed this or learnt from it, but potentially, the opportunity to realise what she didn’t know could have been a catalyst for learning.

In Example 6.8 Rosie is now talking with a new conversational partner. She has the opportunity to try out a language form that she is not sure about – ‘d’accord’. Having used it, she then queries whether it was appropriate in the context in which she used it.

Example 6.8

S Salut Hi Rosie Ça va? How are you? S Ça va. Très fatigué Alright. Very tired. Rosie D’accord. Like does that make sense? I am pretty sure it does. It is meant to be like I agree because like can I just check that? I just want to check that so that I don’t say it in the test. Ok. […]

A little later in the lesson the teacher asks for questions and Rosie seizes this opportunity in Example 6.9.

Example 6.9

Rosie Does accord mean ok or does it also mean I agree? T D’accord – ok. Je suis d’accord – I agree.

We can see from Examples 6.5 to 6.9 that Jessica had intended the practice that students were engaged in to promote fluency and to allow them to work with the language that they had already been introduced to in class. Yet, it also provided opportunities for students to push their language output, to notice what they did not know, to try out and experiment with language and to get feedback and help from each other. All of these processes could have contributed to new language learning because on these occasions students were working at a level slightly beyond what they could cope with, as Reference Ortega and DeKeyserOrtega (2007) describes (see Chapter 4), at 0 + 1, or output plus one level (in a mirror image of Krashen’s input + 1 metaphor, see Chapter 3).

In Chapter 1 we discussed the importance of environmental support in promoting learning in the classroom. In this section we see good examples of environmental support in the trust and support that students experienced from and gave each other as they practised language together. The positive and collaborative ways in which they worked led to opportunities for language learning.

The Third Principle Is that There Should Be a Focus on Task-Essential Forms

Ortega claims that there is a need for intensive practice of specific aspects or forms of a language. When a teacher knows what particular language structure, or language structures, they think that their students need to practise, it can be a challenge to design a practice activity or task that requires them to use this structure or structures. In other words, this/these structure(s) need(s) to be essential, so that it is not possible to complete the task/activity without using it/them. The ‘task essential’ form in the snake game would appear to be the expression ‘aimer faire’ (‘to like doing’). In the interview, Jessica identifies this expression as one that is prominent. As we see in Example 6.10 where Francesca and Hannah play the game during the first lesson, the game succeeds in having students practise this structure intensively (as underlined).

Example 6.10

Francesca Qu’est-ce que tu n’aimes pas faire? What do you not like doing? Hannah Mmm je n’aime pas faire de la danse Mmm I don’t like dancing Francesca Qu’est-ce que tu aimes faire avec ton portable? What do you like doing with your mobile? Hannah Avec mon portable j’envoie des SMS I send text messages with my mobile [then 4 turns later the exchange continues] Francesca Qu’est-ce que tu aimes faire avec tes copines? What do you like doing with your friends? Hannah Avec mes copines j’aime faire . . . j’aime faire le danse. With my friends I like … I like dancing

This structure was salient or obvious to at least one learner, Rosie, as she played the game during the lesson. This is evident from her response to the following question in the written questionnaire that she filled out at the end of the lesson:

What did you learn today in your French lesson? Please think of as many things as possible and write them below.

To summarise, in this section we’ve illustrated features of optimal practice activities. They are interactive

and meaningful,

and they provide opportunities for learners to focus on form or on specific language structures. These three features are important because they have the potential to help learners notice, reflect on,

and experiment with language. When learners have these opportunities, they are more likely to acquire language.

In this next section, we return to the idea of Nation’s four strands and focus on what Nation says about language practice.

Nation’s ‘Fluency Development’ Strand

As we have already seen, Reference NationNation (2007) argues that a well-balanced language course should consist of four strands.

Nation’s Four Strands

Practice allows for the development of ‘fluency’. However, Reference NationNation (2009, p. 2) paints a negative picture of the attention that is given to this strand: ‘there are courses that give useful attention to language features, but that do not provide opportunities for the learners to become truly fluent in using what they know’.

As well as emphasising the need for adequate practice time, Nation outlines what he considers are the essential conditions. Two of these we have already discussed in this chapter; that is, firstly, the need for students to be working with language that is largely familiar to them and, secondly, the need for a focus on receiving or conveying meaning.

Two other requirements for building fluency are the need for some pressure or encouragement to perform at a faster than usual speed, and the need for a large amount of input (for the receptive skills of listening

and reading)

and output (for the productive skills of speaking

and writing).

In other words, time on task is important to building fluency. We could argue that in Jessica’s classroom, there was evidence of a large amount of output in that the students spent the major part of two fifty-minute lessons either interacting in pairs

or using the language they had practiced orally to write about themselves. In the lessons we observed in Jessica’s classroom, there was no mention by the teacher that students should increase their speed at any stage of the practice. However, it seems that at least one student was aware that this was the aim. In a written questionnaire at the end of the lesson, Rosie wrote in response to the question:

Please write one thing that you liked about today’s lesson. If there was nothing, that is ok.

Another very effective way of promoting fluency in oral language that makes use of time pressure

is the 4/3/2 technique (Reference Nation and MacalisterNation & Macalister, 2010). In this activity, learners work in pairs, with one acting as speaker and the other as listener. The speaker talks for four minutes on a specific topic, then moves to another pair and gives the same information to a new partner, but this time in three minutes. Lastly, the speaker gives a two-minute talk on the same topic to another new partner.

Reference Nation, Macalister and NationNation (2011) makes another important point about language practice, although this advice need not only apply to the ‘language practice’ context. He says that in language practice, the students need to be doing the work. In other words, there should be relatively little ‘teacher-fronted’ classroom focus.

And What Did the Students Think?

Eight students gave permission for their exchanges to be audio-recorded as they participated in Jessica’s lessons. Five students in this class filled out a questionnaire of their perceptions at the end of each lesson. On the first lesson, they were all positive, ticking enjoyable or very enjoyable (the top two from a choice of five descriptions). In the second lesson, three remained positive, but one ticked ‘neutral’, stating that she was tired and found it hard to concentrate and the other ticked, ‘not very enjoyable’, explaining ‘I didn’t get to sit with my friends’. This comment underscores the importance of peer relations for the adolescent language learner (see Chapter 1).

This student feedback suggests that overall students found the practice activities a positive experience, but enthusiasm wasn’t sustained for all, over the two lessons. A difficulty in practice is that it requires persistent effort, and quite a deal of creativity on the teacher’s part to encourage students when interest or confidence flags.