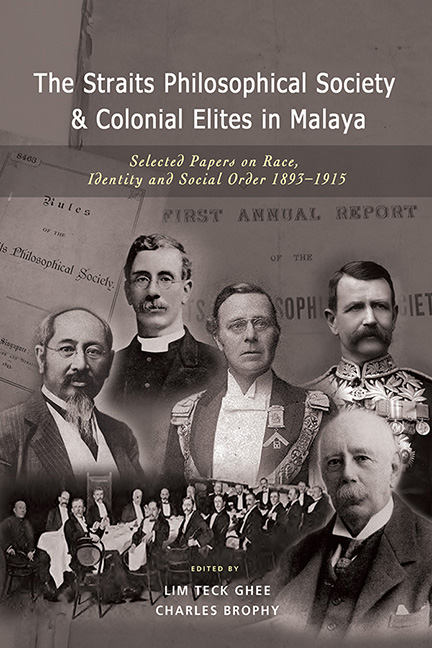

The Straits Philosophical Society and Colonial Elites in Malaya

The Straits Philosophical Society and Colonial Elites in Malaya 15 - The Reformation of British Malaya

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 January 2024

Summary

Editors’ Note

A more critical tone towards colonial government was also evident in James Aitken’s essay of 1907. Aitken, a Queen’s Scholar from Singapore and a lawyer who practised alongside Song Ong Siang, came to criticize in the Society what he saw as the failings of British policy in Malaya. The central issue of the ensuing debate with Arthur Knight was the standards to which British colonial policy was to be held. For Knight, British achievements had to be understood in relation to the condition in which they had found the Malay Peninsula and the improvement of this condition. Aitken, on the other hand, was concerned with the British failure to attain for the colony a fuller level of economic and social development and for the unevenness of their achievements. This debate came to focus particularly on the position of the Malays, and British responsibility to include them within the development of the colonial economy and colonial society. On his part Aitken would argue in a manner that was a precursor of later debates around affirmative action that whilst the Malays were “not likely for a long time to reach the standard of the European, Chinaman, or Tamil, he should be encouraged by Government, and the other races should even be slightly handicapped in order to advance him”. Arthur Knight’s critical response similarly emphasized objections to affirmative action which anticipate arguments raised in future debates. For him the current status of the Malays was an outcome of their nature. He argued that they had the formal right to study medicine and join the legislative council but lacked the inclination. He was of the opinion that their improvement could not therefore be forced. Moral reform and improvement for Knight appeared to be confronted with the reality of racial difference.

For the purposes of this paper British Malaya may be taken to be the Straits Settlements and the Federated Malay States, leaving out of account Labuan, British North Borneo, and Sarawak.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Straits Philosophical Society and Colonial Elites in MalayaSelected Papers on Race, Identity and Social Order 1893-1915, pp. 212 - 230Publisher: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak InstitutePrint publication year: 2023