Estonia is a small European country with a population of 1.4 million and an area of circa 45,000 square kilometers. It is one of the three Baltic countries located beside the Baltic Sea. It has a land border connecting with Russia and Latvia and it is only 80 kilometers by sea from the capital of Finland, Helsinki. Only some thirty years have passed since Estonia regained independence in 1991, when the Soviet Union dissolved. It had already declared independence much earlier, in 1918, after World War I, but was occupied by the Soviet Union from 1940 until 1991. In 2004, Estonia became a member of the EU and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

Estonia’s energy policy has been heavily oriented toward national security concerns and attempts to break connections with the Russian energy system. The general orientation has been to reduce the geopolitical threat of Russia, that is, negative security. The development of oil shale has been important to Estonia in its disconnection pursuits from the Russian energy supply and, hence, this has slowed down Estonia’s zero-carbon energy transition. Yet the location of the oil shale production has been close to the Russian border, reducing the security of this energy type due to potential Russian intervention. Gradually, Estonia has stopped commercial electricity trade with Russia, despite still-existing infrastructural connections, and has aimed to cover consumption by using domestic sources while also expanding energy interconnections with the EU (Kama, Reference Kama2016). This decision made Estonia the EU member state with the lowest energy import dependence. Estonia’s reliance on energy imports reduced from 34 percent in 2000 to less than 5 percent in 2019.Footnote 1 From 2010, Estonia became a net exporter of electricity generated from oil shale. However, by 2020, the country’s energy import dependence had increased again to 11 percent (Statistics Estonia, 2023), partly due to the emission reduction requirements of EU climate and environmental policy.

Since the early 1990s, this country has experienced a relatively rapid development, from being part of the “laggard” Eastern European Bloc to a nation with advanced digital technologies. Despite the general innovativeness of Estonia, its energy system has been largely tied to an old fossil fuel-based regime, in particular oil shale, and dependence on Russian electricity and gas networks. Oil shale is “an energy-rich sedimentary rock that can either be burned for heat and power generation or used for producing liquid fuels” (IEA, 2019, p. 11); it has a carbon intensity similar to coal but is less efficient as a fuel due to a lower share of organic matter. The mining of oil shale began officially in 1918 when a government decree made open pits the responsibility of a particular department in the Ministry of Trade and Industry (Holmberg, Reference Holmberg2008). Estonia’s energy supply has relied almost entirely on domestic oil shale since 1991.

Oil shale consumption dropped dramatically, over 40 percent, during the 1990–1995 period, in connection with Estonia gaining independence.Footnote 2 However, after 2000 there was a gradual increase in total oil shale consumption, peaking at 15 million tons in 2013, a 42 percent increase on 2000 (Statistics Estonia, 2023). This was followed by a gradual decline, and then sudden drops to 5.9 million tons in 2019 and 3.1 million tons in 2020 (see Figure 5.1). This decline in the share of oil shale was caused by rising CO2 emission quota prices, making this type of energy less competitive in the European electricity markets (Vasser, Reference Vasser2021). In addition, some large oil shale plants had reached their full operational age. However, the data also shows a rather rapid increase of oil shale consumption more recently, in 2022, when the energy crisis hit Europe following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Figure 5.1 Total consumption of oil shale (thousand tons), 2000–2022.

The overall share of natural gas has been low within Estonia’s total energy consumption, while the gas used in Estonia was mostly supplied from Russia until 2015. A Russian company, Gazprom, was the main supplier to all the Baltic countries and the only gas supplier to Estonia, meaning these countries were all vulnerable to sudden disruptions (Pakalkaitė and Posaner, Reference Pakalkaitė, Posaner and Godzimirski2019). This is illustrated by the gas dispute in 2009 between Russia and Ukraine that left many EU countries that relied on Gazprom with severe shortages (Štreimikiene et al., Reference Štreimikiene, Strielkowski, Bilan and Mikalauskas2016). Estonia’s concerns about Russia’s tactics to maintain a monopoly of gas transit to Europe has resulted in it denying the Nord Stream pipeline access to its territorial waters (Crandall, Reference Crandall2014). In December 2014, a new terminal for liquefied natural gas (LNG) was opened in Lithuania, which allowed Estonia to diversify its supply from Gazprom (Pakalkaitė and Posaner, Reference Pakalkaitė, Posaner and Godzimirski2019). A new gas pipeline, Balticconnector, was opened between Finland and Estonia in 2020, connecting gas markets in the two countries, with the aim to create a regional Baltic–Finnish gas market. The pipeline was massively damaged in fall 2023 halting supply. Investigation to this incident was inconclusive regarding intentionality of this damage, with the likely cause being damage by a ship anchor. Almost 40 percent of natural gas is used in district heating, but, due to increasing natural gas prices, district heat producers are increasingly considering local renewable fuels (MEAC, 2022).

Estonia met the EU target for renewable energy, 25 percent, in 2011, primarily through biomass and wind power, although the former caused degradation of biodiversity. The shares of renewable energy and combined heat and power (CHP) in the country’s electricity production have rapidly expanded. In 2021, renewable energy amounted to 38 percent of total energy and 29 percent of electricity production, while oil shale still made up over a half. Of renewable electricity production in 2022, about half was from wood chips and waste, a quarter from wind power, and 20 percent from solar power (Statistics Estonia, 2023). The expansion of the wind power niche has been limited owing to concerns related to the effects of wind turbines on the defence sector’s air surveillance radars. This issue is explored later in this chapter.

This chapter analyzes the first country case study of this book. It creates the context of energy and security regimes in which the interplay of energy and security policies occurs. It then follows the analytical foci presented in Chapter 3: the perceptions of Russia as exerting landscape pressure on energy transitions, policy coherence and integration between energy and security, and positive and negative security aspects related to niche development and regime destabilization via three cases. These are: the phaseout of oil shale, the effects of wind turbines on defence air surveillance radars, and desynchronization from the Russian electricity system. The empirical data analyzed include government energy and security strategies published during 2006–2021 and two rounds of interviews with energy and security experts, between October 2020 and May 2021 and between January and March 2023. These primary sources have been complemented with the literature.

5.1 Energy Regime

As outlined, the key sources of the Estonian energy system have been oil shale, imported natural gas, and a range of renewable energies, especially wood chips and waste streams. Unlike in Finland (Chapter 6) and the UK (Chapter 8), Estonia does not have any nuclear power. A government-level working group was established in 2021 to investigate the possibilities of establishing small modular reactors. One complication is that Estonia has no experience of regulating nuclear power so proceeding with this would require drafting new legislation and increasing nuclear expertise.

A developing renewable energy niche is that of offshore wind power, for which there are significant plans. The planned developments include two sites in the Gulf of Riga and near the western island of Saaremaa that would cover 1,700 square kilometers and provide circa 7 gigawatts (Vanttinen, Reference Vanttinen2022). By 2030, the Estonian government aims that 65 percent of total consumption will be provided by wind power (CPTRA, 2023). Maritime planning was advanced in early 2022 to investigate the effects of offshore wind on defence, shipping routes, and the environment.

Besides renewable energy development and in direct opposition to the aim to decarbonize the energy system, new applications to exploit oil shale and gas are still being made. For instance, the Estonian Ministry for Economic Affairs and Communications has been interested in the shale gas developments in North America, which are a result of substantial shale gas deposits found in the US (MEAC, 2022). In addition, connected to the need to diversify gas supplies, biomethane from local bio-based raw materials has garnered increasing interest. In 2021, Estonia had two biomethane production plants, producing up to 40 percent of the gas used in transport.

As Estonia is a small country, its administrative structure concerning energy and climate governance is relatively simple. The Ministry of the Economic Affairs and Communications (as of July 2023 the newly established Ministry of Climate) oversees Estonia’s energy policy. The Ministry of Finance has some responsibilities regarding budget preparation for the national “Energy and Climate Plan.” The Ministry of the Environment (from July 2023 onward the Ministry of Climate) coordinates environmental policy and the management of natural resources. A state-owned company for oil security of supply was established in 2005, which was reorganized as a broader security-of-supply organization akin to the Finnish National Emergency Supply Agency (NESA) (see Chapter 6) in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. A governmental Climate and Energy Committee was established to operate during 2019–2021, with the prime minister chairing this committee, which also had the Minister for the Environment, the Minister for Defence, and the Minister for Foreign Affairs among its members. In 2021, the government established a Green Policy Steering Committee, chaired by the prime minister, to coordinate the implementation of “green policy” across sectors. The ministerial committee is supported by an expert group and makes proposals to the government. In 2023, an expert-based Climate Council was established.

A rather unique feature of Estonian energy policymaking is that there is no agency level. Energy agencies typically regulate and monitor operation of electricity and gas markets as well as emission reductions, or advance energy efficiency. In Estonia, instead, the electricity and gas transmission network operator Elering effectively plays the role of an agency in security of supply. According to an expert interviewee, it is “a quasi-security police or authority.” This role is at least partly due to the large role of electricity in Estonia’s energy transition, namely desynchronization and offshore wind efforts. In addition, before the 2020s, the security-of-supply organization only addressed oil and not electricity. Some regard Elering’s position as a conflict of interest, resulting in little expertise in the public sector:

Sometimes you get the impression that Elering plays the energy agency’s role, rather than some big kind of a state agency or energy and climate agency or energy agency or you know whatever you call it, so it’s certainly a structural weakness.

Eesti Energia, a fully state-owned company, is the main producer of electricity. Ninety percent of oil shale-based electricity was produced by Eesti Energia in 2020 (Sillak and Kanger, Reference Sillak and Kanger2020), but it aims to stop production of electricity from oil shale by 2030 and increase renewable energy production. The company is among the largest employers in Estonia and it is free to make its own investment decisions irrespective of its state ownership (Tõnurist, Reference Tõnurist2015). The dominance of this state-owned monopoly meant that, until 2014, there was little distinction between the management of the oil shale industry and government energy policy; an attempt to reduce the influence of the industry on energy policymaking was made by transferring the company’s ownership from the Ministry of Economic Affairs to the Ministry of Finance in 2014 (Kama, Reference Kama2016). Nonetheless, it still appears that the company has more influence on Estonian energy policy than policymaking has had on the company.

Several political figures and civil servants in Estonia have held both ministry positions and positions in the energy industry. For example, Taavi Veskimägi has been the Minister of Finance (2003–2005) and the director of the transmission system operator Elering (2009–2023). In addition, at least four individuals interviewed have worked for the energy sector (Elering or Eesti Energia) and the Ministry for Economic Affairs, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, or the Ministry of the Interior. This is partly explained by the small population of the country, that is, there is a limited number of experts, but also by the nature of informal energy relations and the tightknit relations of the “energy elite.”

Another important feature is the relatively late growth of the formalized environmental movement in Estonia. The Estonian Green Party was only established in 2007, despite the fact environmentalism has played an important role in Estonia’s independence pursuits since the 1980s (Auer, Reference Auer1998). The Renewable Energy Council was formed in 2011 by renewable energy entrepreneurs and associations, becoming a vocal advocacy group and proposing a plan for transitioning the country’s energy system into a 100 percent renewable energy system (Sillak and Kanger, Reference Sillak and Kanger2020).

Since 2004, when Estonia became an EU member state, its energy and climate policy has been shaped by the EU. Estonia had already applied for membership in 1995 but, according to an interviewed expert, was unable to join then because its oil shale industry conflicted with EU environmental objectives. Eventually, the EU agreed to give oil shale a temporary status, prolonging the deadline for renovating old power plants to meet EU air-quality standards until 2016, allowing Estonia until 2013 to fully open up its electricity market, and allocating research and development (R&D) support for reducing the environmental impacts of oil shale (Sillak and Kanger, Reference Sillak and Kanger2020).

Despite these early concessions, Estonia has taken some time to liberalize and decarbonize its energy regime. When the electricity market was fully opened up in 2013, Eesti Energia maintained a significant role in the market. Throughout the years, Estonia has managed to keep large part of the energy production under state ownership, even though this is at least partly contradictory to EU energy market rules. Kama (Reference Kama2016) has noted that “[t]his state-regulated and extremely carbon-intensive sector has shown remarkable resistance to liberalisation, unbundling and privatisation; the three neoliberal modes of energy governance that underpin the policies of the EU, the OECD, and international donor agencies” (p. 836). She continues:

The government’s recurrent flirtations with privatisation further demonstrate how energy security arguments blur the distinction between market and non-market practices in state policy, for conservative and liberal parties alike. Despite two serious attempts to induce private investment capital for replacing the Soviet-era thermal units commissioned over forty years ago, the energy monopoly remains fully owned by the state.

Likewise, oil shale has not been addressed to the degree it should have according to EU requirements. When oil prices declined and the price of EU emissions-trading permits rose, the oil shale market became less lucrative. In response to this, the Estonian government lowered environmental taxes to support the industry, justifying this action by claiming the fuel was important for national interests, such as security and employment (Holmgren et al., Reference Holmgren, Pever and Fischer2019). In 2019, the International Energy Agency (IEA) noted in its country review of Estonia that “the negative externalities of fossil fuels are currently not sufficiently reflected in the existing tax rates and there is a significant number of tax exemptions and reduced tax rates which are counterproductive for meeting the climate targets” (IEA, 2019, p. 28). An interviewee noted that:

We still thought that shale oil is going strong and oil shale burning is fine, so, [you saw] even some misguided investments like Eesti Energia putting up a new unit, spending over half a billion euros to continue burning oil shale and so on because the focus was on reducing the SO2 emissions rather than CO2 emissions.

During 2017–2018, Estonia prepared some key documents for its medium-term energy and climate policy, including the “National Development Plan for the Energy Sector until 2030” and the “Estonian National Energy and Climate Plan 2030,” submitted to the EU. Estonia aimed to reduce greenhouse gases 70 percent by 2023 and 80 percent by 2025 by increasing renewable energy (above 25 percent of total energy use), while simultaneously maintaining a high level of energy security by limiting fuel imports, diversifying energy sources and supplies, and connecting with the European electricity market. In the baseline year for emission reductions, 1990, the greenhouse gas emissions were so high, 40,233.79 tons of CO2 equivalent, that it was relatively easy to reduce these by 20 percent by 2020 as required by the EU. The greenhouse gas emissions had dropped almost by half already by 1993 and were on the same level until 2018. Further, Estonia aimed to produce 50 percent of domestic final electricity consumption via renewables by 2030. Wind energy and solar energy for electricity production were planned to be further developed, and biomass use increased for heating. Biofuels and hydrogen fuels were also to be developed, the latter being on the agenda of the Green Policy Steering Committee. The plans were updated in fall 2023. The revised plans show an aim to achieve 24 percent reduction in emissions by 2023 compared to 2005, and net-zero emissions by 2050.

Energy independence from Russia has been the cornerstone of Estonian energy policy since its independence. Its EU membership has, however, forced Estonia to change its traditional energy policy and pay attention to the decarbonization of its energy system, which has impacted its energy independence to some extent. This decarbonization process has been slow on both security and economic grounds. Despite the ambitious plans for renewable energy and energy efficiency, oil shale has continued to play an important role in energy policy. The “National Development Plan for the Use of Oil Shale 2016–2030” stated that oil shale will remain an important fuel. The “National Development Plan for the Energy Sector” also mentioned the possibility of new investments in the oil shale sector to increase energy exports. If this continues, it will be hard to lower Estonia’s ecological footprint. Figure 5.2 summarizes the key aspects of the Estonian energy regime.

Figure 5.2 Key aspects of Estonian energy policy.

5.2 Security Regime

In Estonia, security policy is the responsibility of the Ministry of Defence. The Ministry of the Interior and its agencies play a supportive role, with responsibility for policing, border control, rescue, migration, and immigration management. For information security, different ministries have their own responsibilities, coordinated by the Ministry for Economic Affairs and Communications. The ministries of defence, of the interior, and of foreign affairs also have important tasks with regard to cybersecurity. At the agency level, the Foreign Intelligence Service and Estonian Security Policy Board are important.

Estonia joined NATO in 2004, and this move has had a large impact on its security policy and defence spending. The latter has gradually increased from 1.39 percent of GDP in 2006 to 2.35 percent in 2022. After Russia’s actions in 2014 in Crimea, Estonia has become “a meaningful player in NATO’s management of renewed Russian security threats” (Studemeyer, Reference Studemeyer2019, p. 789). The capital city Tallinn hosts the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence. Estonia has developed leading expertise in cybersecurity for NATO, alongside with prioritizing its membership fees to it, even during times of economic austerity (Studemeyer, Reference Studemeyer2019).

Estonian Defence Forces were reestablished immediately after independence (Piirimäe, Reference Piirimäe2020). They consist of 4,000 people in permanent readiness and another 4,000 in supplementary reserve. Thirty thousand reservists have also been trained by the Defence Forces (Estonian Defence Forces, 2023).

Security and defence governance are strongly based on the country’s history with Russia. Alongside the other Baltic countries, after its independence Estonia sought security by integrating with Western structures: the EU and NATO. The latter led to a revision of security and defence strategies that are reactive to changes in the surrounding geopolitical environment (Piotrowski, Reference Piotrowski2018). Despite becoming an EU member state, Estonia’s foreign policymakers have maintained a traditional realist approach to the East, their security policy “driven by an existential concern about national security,” with the hard security guarantees of NATO being a cornerstone of the country’s security policy (Raik and Rikmann, Reference Raik and Rikmann2021, p. 606). These reflect thinking along the lines of “negative security” (cf. Hoogensen Gjørv, Reference Hoogensen Gjørv2012). Eurosceptic views have been present all the time but were marginalized until 2015, when the Conservative People’s Party of Estonia (EKRE) won 8 percent of the parliamentary seats and later expanded its populist presence in government politics (Raik and Rikmann, Reference Raik and Rikmann2021).

The security risk from Russian interference is perceived as tangible even after three decades of independence and before Russia’s attack on Ukraine in 2022. The elevated perception of risk is not only due to historical factors. It has been influenced by the very slow withdrawal of Russian troops after independence, with some thousand soldiers remaining until August 1994 and an “increasingly aggressive Kremlin policy towards its neighbouring countries” (Piotrowski, Reference Piotrowski2018, p. 47).

Security policy in Estonia is based on a broad security concept. This means the capability of the state to defend its values and objectives from military and nonmilitary risks. Security policy aims to guarantee independence, sovereignty, survival, and the constitutional order. The key policy documents for security and defence policy are the “National Security Concept of Estonia” (2017) and the “National Defence Development Plan 2017–2026.”

There is a specific focus on cybersecurity because Estonia is one of the most digitalized societies in the world. Besides Estonians being among the highest internet and mobile broadband users, the country had already installed 100 percent smart electricity metering by 2016, improving network management (IEA, 2019). Cyberattacks from Russia are some of the most concrete threats that Estonia has more recently experienced. Russia considers Estonia as “ideologically unfriendly” and has tried to cause economic disruption by putting pressure on and maintaining tensions between the Russian nationals in Estonia and the Estonian population via cyberattacks (Studemeyer, Reference Studemeyer2019). Following a sequence of nationwide cyberattacks in 2007, Estonia decided to develop its cyber expertise, including the first governmental cybersecurity strategy in 2008, by providing university-level education in this field, and establishing a “cyber defence league” to act under its own military command in case of war (Crandall, Reference Crandall2014).

The trend is, and this is not surprising, that the cyberattacks are increasing every day. And they are just not joking, but we see they’re professional. We see the professionally designed cyberattacks more and more … We could imagine a very dark scenario when the major power plants in this north-east region would be cyber-attacked, and the damage could be really huge. But I can confirm that our public authorities are dealing with that.

Two government strategy documents relate to cybersecurity: the “Digital Agenda 2020 for Estonia” (2018) and the “Cybersecurity Strategy” (2019). This preparedness is valid, as the risk of cyberattacks appear to be rising. Figure 5.3 summarizes the key aspects of Estonian security and defence policy.

Figure 5.3 Key aspects of Estonian security and defence policy.

5.3 Perceptions of Russia as a Landscape Pressure at the Intersection of Energy and Security

This section examines landscape pressure for the energy transition in Estonia, focusing on the ways in which perceptions of Russia as a landscape pressure for Estonian energy policy have formed. Policy documents from the period 2006–2020 mentioned a range of factors that can be interpreted as landscape pressures (Kivimaa and Sivonen, Reference Kivimaa and Sivonen2021). In 2006–2010, these included globally growing competition over energy, risks of cyberattacks, and land-use-related conflicts. At that time, the documents pictured Russia as a substantial landscape pressure and a global superpower ready to utilize military force as well as energy as political tools in international relations. Policy document material was limited during 2011–2015, so landscape pressures were more difficult to detect. Uncertainties in global energy markets and risk of attacks against energy and digital systems were mentioned. During 2016–2020, similar pressures as in the first period of analysis were mentioned. However, Russia was mentioned less, and instead the instability of the global economy and international finance were emphasized. Nevertheless, Estonia has quite consistently perceived Russia as a significant landscape factor, shaping the Estonian state’s actions in energy and security policies.

Perhaps due to deep historical and cultural issues, alongside the rather short period of independence from Russia, perceptions of Russia as exerting a substantial landscape pressure on the Estonian energy regime are prevalent in the expert interviews. Thirteen out of sixteen interviewees considered Russia to be a considerable security risk in the energy–security nexus both prior to and post 2022.

We see a very determined and aggressive Russia, rising from the ashes threatening Europe, Finland and the Baltic States.

There has always been a strong distrust toward Russia, and Russia has demonstrated several times how they might use energy to influence policy.

The impact of this risk is evident in the plan of the Estonian state to desynchronize its electricity system from Russia and in complicating the oil shale phaseout in Ida-Viru County (see details in Section 5.5). The direct impact of this landscape pressure has been the slowed-down destabilization of the domestic (oil shale-based) part of the fossil fuel regime, as such pressure was largely not supportive of renewable energy niche development before 2022 (see also Sillak and Kanger, Reference Sillak and Kanger2020).

Although most of the interviewed experts were in consensus, the perceptions of three interviewees differed. Two experts were somewhat more positive about the influence of Russia, although they still recognized certain risks.

A real conflict between Estonia and Russia, or Russia and Ida-Viru County is very unlikely.

One interviewed politician mentioned that Russia has been a stable energy partner to Estonia and, contrary to others, believed that desynchronizing from the Russian grid might increase instability:

Well on energy side Russia has been a very good neighbor … electricity has been flowing freely all that time and given us this security of the grid.

The perceptions of Russia as a landscape pressure were largely unchanged as a result of the 2022 attack on Ukraine, due to the preexisting negative perceptions. One interviewee mentioned that, after, things were even more openly discussed as a result. Another interviewee noted:

Well, they have lost every bit of trust that we still used to have. I mean we were never really very optimistic, but now we just regard Russia as an aggressor country.

The analysis shows that Russia has been perceived as a dominant landscape pressure for Estonian energy policy from the security perspective. This pressure has remained throughout the studied period, from 2006 until 2023.

5.4 Policy Coherence and Interplay

Policy coherence and integration were studied by focusing on synergies, conflicts, and administrative integration between the policy domains of energy and security/defence. To do this, analyses were conducted on Estonia’s key energy and security policy strategies, published during 2006–2020, and interviews conducted in 2020–2021 and 2022–2023. The results of these analyses have been published in journal articles (Kivimaa, Reference Kivimaa2022; Kivimaa and Sivonen, Reference Kivimaa and Sivonen2021) and some of the key findings are summarized in this section.

It is very clear that security from the Russian threat has played a significant role in Estonia’s energy policymaking – resulting in a rather unique approach among EU countries prior to 2022, when the focus in the EU was mostly directed toward open and competitive energy markets. A moderate-to-high integration of security was already visible in Estonia’s energy policy documents during 2006–2010 – market collaboration with Europe, oil shale, and diversification of supply being the key means to achieve this (Kivimaa and Sivonen, Reference Kivimaa and Sivonen2021). This integration has become even more visible since 2016.

Kivimaa and Sivonen (Reference Kivimaa and Sivonen2021) noted that energy–security integration has been observable in policy objectives, policy measures, and policy processes alike. However, the objectives have been conflicting from the perspective of decarbonization, emphasizing both oil shale extraction and wind power development. In the policy documents of 2016–2020, security was visible in the objective to redefine security of supply for operational continuity even when transmission capacity between EU member states is lost. Among measures, the energy (de)synchronization project has been vital; the institutional change has been easier to achieve, while technologically the project has not yet been completed. Policy strategy documents have also focused on cybersecurity readiness measures and investments in additional prewarning systems for defence to enable offshore wind development. This kind of integration is better achieved by involving Ministers of Defence and of Foreign Affairs in the government Climate and Energy Committee, which Estonia has done. The strong security aspect was also very visible in the use of the term “readiness of war” as an important principle for the development of energy systems. Such language was rarely used in other European countries prior to the events of 2022.

Although security from Russia has played a substantial role in Estonia’s energy policy, the document analysis showed energy issues were not substantially addressed in the country’s defence and security strategy documents; less so than in Finland’s, for example (Kivimaa and Sivonen, Reference Kivimaa and Sivonen2021). This lack of integration may also explain the difficulties and slow progress with offshore wind power expansion.

An analysis of expert interviews from 2020 to 2021 also shows evidence of insufficient formal integration of energy and security policies. Justified on the basis of small country size, it was seen that in areas where policy coherence has been achieved this has been the result of informal connections and bottom-up problem-solving exercises. Strategies, objectives, or shared visions in bringing together energy and security policies have been missing (Kivimaa, Reference Kivimaa2022). Yet some concrete policy decisions have supported improved coherence between energy and security considerations despite the absence of supportive processes. Importantly, these include the desynchronization process and the decision to invest in new radar technology to allow for the expansion of wind power.

As in many countries, the “National Security Strategy” has framed energy as critical infrastructure and a vital element of national defence. This pursuit is mainly visible in the strategy as ambitions to intensify collaboration with the EU, the Baltic States, and the US, and to keep using oil shale in a “rational” manner – instead of more concrete action proposals. The continued use of oil shale has created a substantial conflict with the progress of the zero-carbon energy transition. Another observed potential conflict was the impact of oil shale phaseout on internal stability in Ida-Viru County. This is explained in more detail in Section 5.5.

Despite the existence and acknowledgment of these conflicts, formal mechanisms and strategies for advancing coherence between the policy domains of energy and of defence and security have been lacking. Policymaking has been reliant on informal communications between the actors in charge. There was a lot of divergence in how actors with expertise on energy and security observed this interaction between the two administrative sectors during 2020–2021. Some agreement that the interaction between key ministries has improved did, however, did exist.

On the positive side,

The Estonian public sector is quite small … which means that there is no need to create large and heavy administrative systems. We just meet up with the relevant people and have the discussions and try to find a solution which is workable, and which is win–win for everyone.

We have very little silos in the Estonian government … we’re well connected and well informed about each other’s processes … each and every year it’s getting better and better.

And, on the negative side,

Traditionally these two ministries have been held by different political parties. They are not really communicating to my understanding. Probably there are some ways of communication. I would doubt that.

The ministries still retain quite a substantial degree of latitude in their activities, and we often complain that in this whole comprehensive system of security, there’s still too little coordination and, perhaps, an awareness of each other’s activities and plans and so on between the ministries … which sometimes leads to some clashes like, for instance, there’s this episode of clash between the wind energy ambitions … and defence interests.

While this informal way of working may be a fluid means of policymaking in a country with a population of only 1.4 million people, it allows for a chance element in dealing with potentially pressing issues that tie energy to security and it has reduced the transparency of public administration, as indicated by the interview comments from external actors. As seen with the case of wind power, sustainability transitions may not advance rapidly enough when reliant on informal interactions for integration and coherence. This is also visible in the complications around the phaseout of oil shale; a phaseout that is inevitable if Estonia is to achieve decarbonization of its energy system and the EU emissions target.

A rather significant shift on this front happened following the events of 2022, given that the Estonian state administration had not given much thought to formalizing the energy–security interface before then. A concrete act was that the energy trade with Russia ceased. Another measure departing from previous practice was acquiring the joint LNG terminal with Finland:

This LNG project has been very out-of-the-box thinking, Elering taking an active part in the project due to a government decision. Usually, such projects are left for the private sector.

Several interviewees remarked that energy issues became politicized after the 2022 crisis, but not securitized in their eyes. It appears that some change in narratives occurred although the risks had already been recognized. Perhaps the most obvious change is cross-political party support for continuing oil shale production, which was a more contentious issue before, while some also reported improved understanding of how energy transition can improve security:

I think that political communication is definitely impacted, because everybody understands that we need them [green energy investments] more.

Many narratives have changed, what relates to energy security, what relates to the security of supplies, how the country should guarantee its power supplies and gas supplies … if you think, a year ago, or maybe a bit more, these were not topics at all.

All the parties support the use of oil shale as a strategic reserve in the future, and [the] majority say that we would need also renewables to come to play, more renewables investments, and we have to remove all the obstacles there.

More broadly, some experts saw that the shock from the war created positive synergies between energy and security by mobilizing society and increasing communication and interaction between the ministries. The effect, however, seems to have been an increase in volume rather than formalization of previously informal relations:

We are kind of trying to build up the system which is more reliable … in war situations for example … These are more on the table and thought over how we can handle them.

For the past year, it’s basically everyday communication and maybe it has come down a bit, but at the beginning all this coordination was just massive.

I would say the cooperation is closer, there’s more coordination. We kind of try to be proactive, we try to also have better, let’s say, communication with potential investors who are interested in having some kind of windmill parks or solar energy parks, so we consult them in early stages.

As a result, the administration conducted activities to stimulate the acceleration of renewable energy, such as setting up new, more ambitious goals for renewable energy, speeding up permissions to erect wind turbines, and identifying gaps in legislation potentially hindering renewable energy deployment – contributing to the process of expectation-building in niche development. These measures were influenced by the RePowerEU policy launched in May 2022 by the European Commission in response to the energy crisis:

Everything which is coming from the European side, meaning building the new wind farms or solar parks, must be quicker and must be easier, that we are currently working on, and trying to make everything faster.

There are cases where one wind farm, due to the complexity of the permitting, needed two, sometimes even three, environmental impact assessments, so we are trying to make the processes leaner, quicker, and easier in order to get more renewables in.

The political pressure has made some quite remarkable steps when it comes to, let’s say spatial planning. It used to take a quite a long time from the idea to full windmill for example, … now the process is much … quicker in a way.

At the same time, activities to support the existing fossil fuel regime have continued due to the energy crisis. These include the LNG project, establishing a new natural gas reserve (stockpiling), and slower decommissioning of combustion plants, and these have partially restabilized the regime despite decreasing gas consumption during the energy crisis. The stockpiling was perceived by one interviewee as a shift from market-based thinking to a more security-oriented one.

More broadly, the last few years have seen increased focus on critical infrastructure; in other words, the vulnerability of cross-country underwater energy interconnections on which Estonia is dependent, as well as Russian control over the cooling water used by Estonia’s Narva power plant. One expert noted that this risk had been acknowledged previously but the likelihood assessed as negligible – now all risks are reviewed from a different perspective. Section 5.5 illustrates three different cases that highlight how energy and security have interacted within Estonian policymaking.

5.5 Niche Development, Regime (De)stabilization, and Positive and Negative Security

In the analysis of expert interviews, three specific cases that relate to niche development and regime destabilization clearly emerged in the energy–security interface in Estonia. The first one deals with the importance of oil shale and the potential economic and geopolitical security concerns that are arising from the phaseout of oil shale in one of Estonia’s poorest regions, which also has a significant Russian-speaking population. The second issue connects to the arduous expansion of wind power and how it has been impacted by the operation of the defence regime’s air surveillance radars. The third interesting issue is the desynchronization of Baltic countries from Russia’s electricity system, where the principal driver has been that of national security, but the move can also be seen to benefit the zero-carbon energy transition. Hence, the three issues relate to the destabilization of the existing energy regime, niche expansion, and regime reconfiguration via the desynchronization project.

An emerging issue related to the expansion of the renewable energy niche is the supply of critical minerals and metals needed for renewable energy technologies. However, this is not discussed here as a specific case, because during the 2020–2021 interviews this aspect was not debated as a security-related challenge in Estonia by the interviewees. The topic did receive attention during the later interviews. For instance, a decision has been made to invest in critical materials-related R&D, while expanding mining activity has its own environmental consequences. Developments have also occurred in the manufacturing side. Silmet, an Estonian subsidiary of the Canadian company Neo Performance Materials (NPM), has announced plans to build a magnet factory and an R&D center in Narva. Therefore, the critical materials question is pertinent for the future development of the energy–security nexus in Estonia. Section 5.5.1 discusses the three cases outlined.

5.5.1 Oil Shale Phaseout in Ida-Viru County

Since around 2014, oil shale has contributed up to 85 percent of Estonia’s electricity production (Kanger and Sillak, Reference Kanger, Sovacool and Noorkõiv2020). Except for 2019–2020, this has been a negative development with regard to a zero-carbon energy transition, explained by concerns of national security, economic gains, and energy independence. Estonia has also used its oil shale expertise to advance its position internationally, by developing processing plants in Jordan and the US (Crandall, Reference Crandall2014). Becoming a worldwide expert in oil shale meant that Estonia was recognized by other countries and could make energy alliances. Such alliances led to increasing support for Estonia against the Russia threat, such as the US speaking on behalf of Estonia during its negotiations with NATO in 2004 (Studemeyer, Reference Studemeyer2019).

EU environmental and climate policy has been a significant driver for oil shale regime destabilization in Estonia. For example, in 2018, Eesti Energia announced it would close four old and inefficient oil shale electricity production units in its Narva power station to comply with the air emissions directive (IEA, 2019). Further pressure for the oil shale industry has been imposed by EU decarbonization targets:

Now for the first time in history Estonia has this serious prospective of phasing out oil shale. And phasing out oil shale is a huge political issue.

Most of the Estonian oil shale industry is located in Ida-Viru County, a northeastern region of Estonia at the Russian border. It can be described as a postindustrial area dominated by Soviet industries, where a lot of oil shale industry was developed. After World War II, the region was subject to Moscow’s policy to minimize the number of Estonians in the region by forcing the relocation of Estonians elsewhere and locating Russian people to the region, while many Estonians also made their own decision to migrate to economically more attractive parts of the country (Holmberg, Reference Holmberg2008). In current times, over 80 percent of the population is estimated to be Russian-speaking and over 40 percent to hold Russian citizenship. The region has less than 10 percent of Estonia’s population, and only 58 percent of working-aged people are employed (Statistics Estonia, 2021). It has the highest unemployment rate coupled with low average income (Prause et al., Reference Prause, Tuisk and Olaniyi2019). It is, thus, the most socially deprived region in Estonia and, consequently, the oil shale industry has been an important source of income. Without this industry, the already poor social conditions could become worse (Holmgren et al., Reference Holmgren, Pever and Fischer2019):

Considering that it actually is deindustrialized or postindustrialized, social issues there are pretty extensive. [The] population is poorer than average in Estonia apart from some very rural and forgotten areas in the south of Estonia … We are talking about big cities. In terms of urban population, they are certainly the poorest.

Thus, the decisions regarding oil shale phaseout need be balanced with minimizing further unemployment and economic hardship, and may create risks of internal instability in Estonia and worsen economic insecurity in the region. The interviewees also pointed out a risk of Russian interference in issues in northeast Estonia due to the large Russian-speaking population; a worry that generated especially strong discussion after Russia invaded Crimea in 2014. This is perhaps connected to the failed attempt at independence from Estonia by the city of Narva in 1993 (cf. Sillak and Kanger, Reference Sillak and Kanger2020).

The conclusion of this discussion was very strongly that it is extremely unlikely due to several reasons. People’s well-being and livelihoods are better on the Estonian side of the border than the Russian side. The local population is well aware of that. And of course, Estonia belongs to the EU and NATO … There have been some attempts by Russia to influence and connect there to the Russian-speaking population, but their influence has been very small.

You just tell them, okay, we go away from shale oil because it’s one of the most energy intensive fuels. We close the factories. We close the mining but then the social tensions will even amplify. They will get amplified. The other side of the Narva river would also react to it and maybe add fuel to the fire. We don’t know anything.

Politicians have tried to keep tensions as low as possible with the Russian nationals who, throughout the years, have not integrated well into Estonian society (Crandall, Reference Crandall2014). Effectively, the residents of Ida-Viru County have been found to have the lowest trust of all of Estonia’s regions in the president of Estonia, the public governance, and the judicial system (Ministry of Defence, 2021). The 2023 election result showed that the Russian-friendly United Left Party had increased their popularity by receiving 15 percent of the votes in the region. This debate is also intertwined with the rise of far-right populist politics in Estonia, which has attracted an increasing number of votes from Russian speakers, despite EKRE’s negative stance toward Russia and the rights of the Russian-speaking population. EKRE is against EU climate policy and, in 2020, proposed the withdrawal of Estonia from the EU emissions-trading scheme. There is, however, consensus between EKRE and the Center Party to save the northeastern part of Estonia from collapsing, despite their differences in politics concerning the integration of the Russian-speaking population into Estonian society. EKRE has used the unemployment and self-determination of Ida-Viru County to support its anti-decarbonization rhetoric (Yazar and Haarstad, Reference Yazar and Haarstad2023). In turn, Kersti Kaljulaid, president of Estonia during 2016–2021, very openly communicated to the population of Ida-Viru County that oil shale is the past and a new plan for the region is needed.

Ida-Viru County and its oil shale phaseout is one of the issues that the EU Just Transition Mechanism is trying to alleviate, with attention paid to employment, the environment, and social inclusion:

So, this is where the just transition mechanism and program comes in. We are in Estonia with different ministries and also with the local municipalities working hard to put together a program which could really then pose as [an] alternative, and which would smoothen the transition which is inevitably happening there if the carbon neutrality goal is achieved, as I’m sure it will be.

In 2022, the EU Just Transition Fund awarded almost 19 million euros to launch a magnet factory in Ida-Viru County, which also responds to EU security-of-supply concerns and the dependence on China for magnets (Kalantzakos et al., Reference Kalantzakos, Overland and Vakulchuk2023). The magnets are vital, for instance, in electric vehicles and, therefore, the investment relates both to the economic security of Ida-Viru County and the security of European supply for technical components required in the energy transition (policy synergy).

The aftermath of 2022 saw some revived interest in the use of oil shale. It became competitive against other energy sources when energy prices increased because of the 2022 crisis, and its continuation has received political support since then – indicating a restabilization of the regime. At the same time, however, the goals for decarbonization are pursued, increasing policy incoherence within Estonian energy policy.

We saw sort of a revival of oil shale power generation in Ida-Viru. So, for years before that, the trend in Ida-Viru was that less and less electricity is produced from oil shale, less and less workforce is needed in [the] oil shale industry. Last year, it changed. Last year, those power plants or the energy sector in Ida-Viru recruited, I don’t know, more than 1,000 people back to work, because, all of a sudden, those power plants were needed in the regional energy market and also in Estonia. And, of course, from that perspective, it made people in Ida-Viru think, whether the green transition all of a sudden has stopped, and whether the situation we saw last year is a new normality.

Eesti Energia is still having the goal in its mind to be 100 percent renewable on electricity by 2030, and, by 2040, [in its] entire [energy] production. So, the plans are still there, the plans what to make from oil shale after we don’t produce electricity [from it] anymore. So, the fact that, yeah, now we had to use more, and still we don’t know how much more, we had to use oil shale to produce electricity, but the overall vision is still toward neutrality.

The restabilization of the oil shale regime has been actively supported by the far-right political party EKRE since 2018 (Yazar and Haarstad, Reference Yazar and Haarstad2023), while other political parties began backing this more for security-of-supply and economic reasons from 2022. An energy business representative stated that the old parts of oil shale power plants in Narva have now received an extension from 2023 until at least 2026, because Eesti Energia is required to guarantee a certain amount of dispatchable production capacity until 2026.

5.5.2 Wind Power and Air Surveillance for Defence

Alongside biomass, wind power is one of the key renewable energy sources used in Estonia, with significant plans to expand. It is, therefore, the most promising renewable energy niche for Estonia. The country’s geographical positioning is favorable to wind power production (Crandall, Reference Crandall2014). However, offshore wind-power development has had a complicated beginning, with a lack of marine spatial planning regulation prior to 2015 and strong opposition from residents (Tafon et al., Reference Tafon, Howarth and Griggs2019). Perhaps a bigger problem – and one that concerns national security more closely – has been the conflicting views of the Ministry for the Economic Affairs and the Ministry of Defence regarding the expansion of wind power. This conflict has been openly acknowledged by those working in the domains of energy and security. During the 2020–2021 expert interviews there were differing perceptions of this conflict between the zero-carbon energy transition and national security. In contrast, by the 2022–2023 interviews a more consensus-based view had formed and solutions had been found via investment into new defence air-surveillance radars.

The conflict was substantially drawn out. In 2006, an offshore wind project off the coast of Hiiumaa, with plans to construct 100–200 turbines with output capacity from 700 MW to 1,100 MW, was halted when the Ministry of Defence suspended the permitting processes for all offshore wind proposals (Tafon et al., Reference Tafon, Howarth and Griggs2019). The reasoning at that time related to the need to establish a legal framework for regulating and planning such developments. Another case involved two wind turbines in Ida-Viru County, which had received permission from the Ministry of Defence in 2012 but, when constructed, were higher than initially permitted, so were found to interfere with air surveillance radars and signal intelligence (Koppel, Reference Koppel2022).

The Ministry of Defence faces a technical problem, whereby the increasing height of wind power turbines interferes with the operation of their air surveillance system – vitally important for Estonia: “Wind turbines can affect the ability of radar to detect and track airplanes, resulting in negative impacts on national security capabilities” (IEA, 2019, p. 124). While better siting of wind turbines and upgrading radar technology can offer some solutions, the small land area and the geopolitical location of Estonia have created obstacles – with the result being that planned wind-power projects of over 500 MW have been objected to by the Ministry of Defence (IEA, 2019).

Wind-park dimensions have grown three times since … the beginning of the 2000s … and they are starting to impact some of our defence systems.

There is the issue with radars. Defence radars which cannot function if some sort of wind farm is built right in front of them. So, this is a real serious issue but by now we have overcome it … there has been a decision to build a new radar.

This debate has created quite a lot of conflict between different parties. Some have argued that the Ministry of Defence has prevented the development to an unreasonable extent, while others have been more understanding:

The Ministry of Defence for a long time didn’t want to talk about it. It was like a public secret that we have a radar and we are monitoring what’s going on over borders. But now they said it publicly and it’s not secret anymore.

The Ministry of Defence has been, let’s say, too offensive and not willing to cooperate. Because I think there are solutions that are able to give that clear view back especially to the east side and have also these wind turbines. On the governmental level, we have agreed to build another radar … But I think still it needs a bit [more] cooperation between this Ministry of Defence or security or military side and the enterprise side to meet both objectives.

The processes resolving these conflicts have taken a long time, with some even resorting to court dealings, but some solutions have been found. In 2018, the government established a working group between the Ministry of Defence and wind power developers to clarify national security restrictions on wind power projects – yet, the IEA noted in 2019 that the government had not offered “a clearly defined planning and permitting process that will allow developers to … open a pathway to projects to proceed in a manner that does not excessively impact radar and other national security assets” (IEA, 2019, p. 124). A decision to invest in a new radar, opening up quite a large territory for onshore wind energy in northeast Estonia, was made by the government in 2019.

The process of wind power development has, nevertheless, been extremely slow and reveals a significant conflict between national security and zero-carbon transition policy objectives. Between 2017 and 2021 no new wind turbines were made operational as suitable locations approved by the Ministry of Defence had not been found (Resmonitor EU, 2021). The new radar should become operational in 2024, finally allowing the planned expansion of wind power and removing all height restrictions. The court dealings were also noted by several interviewees in 2023 to have ultimately led to much-improved collaboration and coherence between the ministries:

I would say that for all our offshore or onshore developments, there is quite good cooperation between ministries, starting from the environmental ministry, in terms of our [environmental impact assessments] EIAs, then the planning in our finance ministry, and also from our defense ministry.

The 2022 energy crisis created a new legislative process that aimed to shorten the planning process by allowing some steps to happen in parallel and resulted in extra funds to acquire new air surveillance radars too; the latter found “extraordinary” by an interviewee from the Ministry of Defence. Several new projects in Ida-Viru County have been planned to increase wind power capacity.

5.5.3 Desynchronization from the Russian Grid

Developments in the reduction of oil shale supply, combined with Estonia being a full member of the Nordic electricity exchange Nord Pool, have focused attention on desynchronizing Estonia’s electricity network from Russia. Initially, after regaining independence, the Baltic States were not connected to the Central European grid and had to sign what is called the BRELL (Belarus, Russia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) agreement in 2001, which formalized the countries’ synchronous operation with the Russian electricity system (Juozaitis, Reference Juozaitis2020). A complete synchronization with the Central European electricity network and desynchronization from the Russian power system were announced as mutual strategic priorities by the Baltic States in 2007 (Juozaitis, Reference Juozaitis2020) and have been in preparation since 2009 (IEA, 2019). A principal reasoning for this has been national security, via breaking ties with Russia. Not everyone in the Baltic States was united on this at first. A common perspective was, however, reached from around 2010:

Fifteen years ago, there was a lot of lack of consensus about synchronization with continental Europe or desynchronizing from Russia, so our thinking was not synchronized between the Baltic States at all. So, there’s a very different picture from where we are now.

The last ten years I would say, all the three Baltic States are in cooperation with Finland, Sweden, and Poland to build a network which could be sustainable and could be autonomous also from Russia’s electricity … Up to 2025, all the three Baltic States, according to the plans, should be ready to desynchronize from Russia’s electricity networks.

In 2014, after Russia stopped the flow of gas to Ukraine, causing an energy crisis, the EU also began to pay more attention to synchronization. Two political roadmaps to advance synchronization were signed by the Baltic States, Poland, and the European Commission in 2018 and 2019 (IEA, 2019). The Baltic Synchronization Project, to improve the security of supply of the Baltics, has been supported by the EU to the tune of over one billion euros and is expected to be completed by 2025. The Baltics had planned to stop all electricity trade with Russia once the synchronization was fully complete, but the 2022 events led to the electricity trade being halted early, in May 2022. Until desynchronization is completed, however, the Kremlin is argued to have “a very detailed and up-to-date picture on the situation of Lithuanian, Latvian and Estonian power systems” (Juozaitis, Reference Juozaitis2020, p. 5). In the meantime, potentially strategic information is being passed on to Russia, while the Baltic States have agreed to speed up desynchronization from the timeline initially planned.

Estlink 1, a submarine electricity cable between Finland and Estonia, was opened in late 2006, with national transmission-network operators Fingrid and Elering becoming its owners in 2013; it was followed by Estlink 2 in 2014. Other new connections that have also benefited the Estonian energy system are the LitPol Link between Lithuania and Poland, in 2015, and NordBalt, which began to operate between Sweden and Lithuania in 2016.

Simultaneously, Russia advanced its own desynchronization from the Baltic States. It did so in order to have “a chronological advantage over the Baltic States” and the possibility of unexpectedly withdrawing from the BRELL agreement (Juozaitis, Reference Juozaitis2020, p. 6). An interviewee noted that Russia had already shown its power position by not supplying emergency electricity to the Baltic States in June 2020, when substantial blackouts occurred following disruptions in the electricity network. This caused a tenfold increase in electricity prices, and even worse blackouts would have occurred if Poland had not supported the Baltic countries with an emergency supply of power.

In 2022, Estonia’s electricity market was heavily import-dependent, especially during peak consumption periods (ERR, 2021). For some, this has raised concerns about peak consumption (e.g., cold weather) coinciding with those of the neighboring countries, such as Finland. Thus, diversifying and developing renewable energy is increasingly becoming a priority to reduce energy supply risks (but coexists with demands to continue the oil shale industry). According to the expert interviews, the energy crisis also led to a search for ways to speed up desynchronization, improving the readiness to desynchronize to within twenty hours if necessary (for instance, if Russia interfered with Estonia’s electricity supply):

Now the war has really made all of us understand that it needs to be quicker. Russia cannot be relied upon in any aspects of life. So, we would like to speed it up, but it’s a completely technical issue. It really, it’s mostly about hardware. Meaning that we have to build those, I think in the Baltic countries altogether, nine huge machines which will guarantee this synchronization, frequency synchronization.

The desynchronization project provides synergistic developments for improving Estonia security vis-à-vis Russia and advancing the zero-carbon energy transition. Electricity supplied via the Estlinks and the NordBalt is more likely to be produced fossil-free than that supplied from Russia or produced with oil shale. Further, the desynchronization is connected to policies advancing the use of fossil-free energy sources, with some risks for the security of the energy supply, especially if the expansion of wind energy infrastructure keeps being delayed.

5.6 Concluding Remarks

Estonia is an interesting case of how “negative security” interests, that is, threats to national security and geopolitics, tie into energy policy and how this, on the one hand, complicates and slows down the zero-carbon energy transition while, on the other, has also advanced it to a degree by the country disconnecting from Russian fossil fuel supplies. Energy has been, to a degree, securitized since Estonia’s independence, and is mainly thought of from the perspective of negative security (security against threats; see Gjørv, Reference Gjørv2012). The substantial threat of Russia has been the prevalent landscape pressure on the energy regime, although other landscape pressures have also been noted – such as climate change, cyber risks, and globally increasing energy demand.

Due to the perceived high Russian landscape threat, first, the impact of wind turbine niche expansion on defence radars made the Ministry of Defence cautious about wind power until recently and, second, there has been caution regarding how Russia would react to the phaseout of oil shale located in the bordering Ida-Viru County, which has a large Russian-speaking population. EU just transition efforts in connection to supporting the oil shale phaseout, that is, regime destabilization, and to new industrial activity in Ida-Viru County, have introduced an element of “positive security” into the Estonian energy–security nexus. These efforts have addressed the well-being effects of the energy transition in this relatively poor region. Yet this is contrasted with diverging political interests related to resistance to EU energy policies.

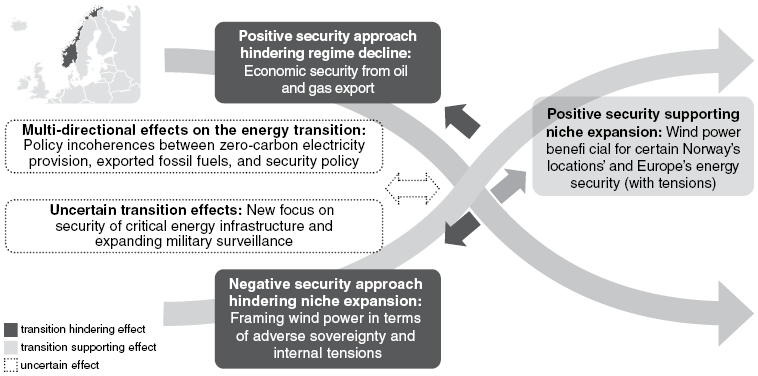

Progress around electricity network integration with Central Europe, which reduces the energy independence of Estonia, resonates with ideas around redefining energy security by accessing cross-border grid communities (cf. Blondeel et al., Reference Blondeel, Bradshaw, Bridge and Kuzemko2021). Yet this aim coexists with the old security narrative constructed around oil shale and energy independence. Relatively little attention has been paid by policy actors to the security implications of the expansion of the energy “niches,” such as solar and wind power, while these implications have clearly increased via newly emerging attention paid to critical materials. More broadly, the extensive efforts already made by Estonia in cybersecurity will also help address the security implications of a new energy system based on renewable energy and the expanding interconnected electricity system. Figure 5.4 summarizes key energy security aspects and their impact on energy transition in Estonia.

Figure 5.4 Key energy security aspects and their transition impacts in Estonia, 2006–2023.

The events of 2022 changed the energy–security nexus. Although security was already present in energy policymaking (more so than the presence of energy in security policymaking), the dialogue became more open after 2022. New solutions for wind power were sought even more actively, with additional radars enabling wind power niche expansion as a measure to improve the security of energy supply. At the same time, however, fossil fuels were restabilized by a new gas reserve, a joint LNG terminal with Finland, and improved political consensus about continuing oil shale production at least for some time. It remains to be seen how these two aims will be balanced in the years to come.

The conflicts situated on the energy–security interface involving oil shale phaseout and the expansion of wind power have had a significant hindering effect on the zero-carbon energy transition in Estonia. These conflicts are unlikely to be resolved immediately due to heightened attention on geopolitical security since Russia’s attack on Ukraine in the winter of 2022. However, recent institutional changes have supported the zero-carbon energy transition, most importantly the goal for 100 percent renewable electricity by 2030, set in 2022. Nevertheless, the EU decarbonization targets and Estonian renewable energy niche actors face a counterforce of strong and established energy regime actors and entrenched party politics. The perceptions and established networks of these regime actors may be hard to overcome. Informal governance structures could be employed for flexibility but may also cause a barrier for new entrants and result in a lack of transparency regarding the energy–security nexus.

Finland is a small Northern European country in population terms, with only 5.5 million residents. Yet it covers a rather large geographical area – 338,440 square kilometers. The country is situated between Russia in the east, Sweden in the west, and Norway in the north. Estonia is only around 50 kilometers away, across the Gulf of Finland. In the past, Finland has been both a part of Sweden and of Russia, with independence gained in 1917. Both historical connections have partly influenced energy policymaking in Finland, and the country has had active energy trade across eastern and western borders, with the former halted after Russia attacked Ukraine in 2022.

Since World War II, Finland has gradually transformed from an agricultural society to a technological one, where the development of the forest and telecommunications industries was particularly significant. The forest industry has had a profound influence on both the demand for energy and the use of forests. Early on, the industry became an energy producer because postwar industrialization raised energy consumption. Hence, forest industry companies invested in electricity production from hydropower and established their own energy company, Pohjolan Voima (PVO), in 1943. In the 1970s, PVO expanded with condensation and nuclear power plant investments. Innovation in pulp and paper production processes enabled forest industry companies to produce bioenergy via their byproducts from the 1980s and 1990s onward, improving the energy economy of the forest industry. After recession in the early 1990s, the telecommunications industry acted as a spearhead for innovation policy. This industry experienced somewhat of a decline after Microsoft purchased global telecoms leader Nokia in 2014 and, later, ended most of its operations in Finland.

Finland is a rather interesting case to study energy–security relations for multiple reasons. First, its domestically available fuels are limited. Besides wood fuels, Finland uses peat in energy production. Peat provided 7 percent of total energy consumption in its peak year in 2007 but, in 2021, was reduced to 2.7 percent of total energy consumption (Statistics Finland, 2023), with a policy goal to halve the use of peat from the 2020 level by 2030 (Figure 6.1). During the 1993–2012 period, peat provided a minimum of 5 percent of Finland’s energy consumption. A strong peat lobby has existed since the 2000s, utilizing security as an argument when favorable. One campaign occurred after the 2006 gas disruptions between Russia and Ukraine, resonating with fears and concerns about energy availability and price (Lempinen, Reference Lempinen2019). Following the events of 2022, policies for the peat phaseout were temporarily relaxed and an emergency stockpile of peat created. This case is explored further later in this chapter.

Figure 6.1 Percentage shares of peat in Finland’s total energy consumption, 2000–2022.

Second, Finland is a neighboring country to Russia, with a 1,340-kilometer shared border, which has meant defence preparedness since Finland’s independence in 1917. However, the country also experienced a culture of “Finlandization” after World War II, described as the “adaptive acquiescence to the will of the Kremlin during the Cold War” (Arter, Reference Arter2000, p. 688). This was followed by the search for positive business relations with Russia and with the avoidance of negative remarks toward Russia in energy policy, and more generally in public discussion. Even after the EU imposed sanctions on Russia after the annexation of Crimea in 2014, Finland kept shoring up its relations to Russian energy value chains and maintained the framing of Russian energy (merely) as an economic topic (Höysniemi, Reference Höysniemi2022). At the same time, Finland has maintained strong territorial defences in the post-Cold War era due to its historical experiences with Russia (Pesu and Iso-Markku, Reference Pesu and Iso-Markku2020).

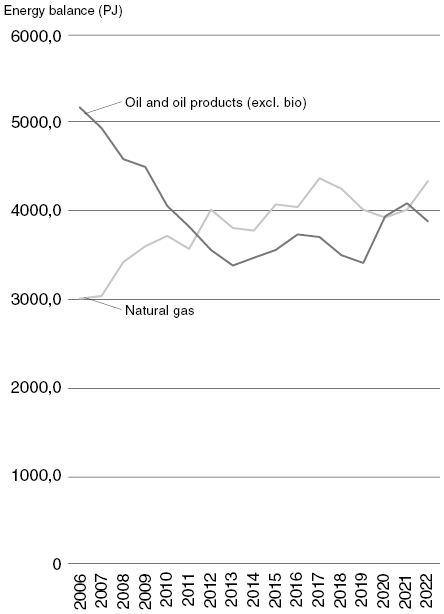

Third, in 2019, the coalition government led by the Social Democrats set an ambitious climate policy goal of a carbon-neutral society by 2035, while the previous government had decided to ban the use of coal in energy generation by 2029. These moves have been supported by the already declining trend of the share of fossil fuels in Finland’s energy production from about 2010 and an acceleration of new renewable energy sources, especially wind power, from about 2014. During the initial study period 2006–2021, prior to the European energy crisis, the share of oil decreased from 25 percent to 19 percent, coal from 14 percent to 6 percent, and natural gas from 11 percent to 5 percent (Statistics Finland, 2023). While the overall share of natural gas was low in 2022, this was still problematic for Finland because all the natural gas had been imported from Russia. Finland managed to secure a liquefied natural gas (LNG) vessel to compensate for some gas supplies. This is the setting in which the analysis of security and energy transitions takes place.

This chapter presents the country case study of Finland. It first describes Finland’s energy and security regimes. It then continues with the analytical sections, drawing on Chapter 4: namely, the perceptions of Russia as a landscape for energy transitions; policy coherence and interplay between energy and security regimes including the level of securitization; and, finally, positive and negative security related to niche development and regime (de)stabilization. The project this book is based on studied Finland’s energy and security-related government strategies published since 2006 and conducted two rounds of interviews with energy and security experts, the first between September 2020 and April 2021, and then the second between December 2022 and January 2023. This chapter draws on these materials and on related literature and selected policy reports.

6.1 Energy Regime

The energy sources of the Finnish energy regime are based on a mix: (relatively limited) domestic fuels (wood-based fuels and peat) and imports of coal, oil, and natural gas (which have been significant since World War II). Therefore, wood has been an important energy source directly and via forest industry byproducts. The decarbonization of the electricity sector has already reduced dependence on these energy forms but transport – and to a lesser degree heating – still rely on imported oil and natural gas. Overall, the energy profile has been variable with no single source dominating.

Finland has a relatively fixed amount of hydropower as an important balancing capacity, with its further construction restricted since the 1980s for nature protection reasons and because the largest rivers were already utilized for hydropower in the 1960s. While, in the 1950s, over 90 percent of Finland’s electricity was produced by hydropower (Kivimaa, Reference Kivimaa, Lafferty and Ruud2008), hydroelectric plants began to face opposition from local communities due to disrupted fishing and farming activities, leading to increased support for nuclear power in the 1960s and 1970s (Myllyntaus, Reference Myllyntaus1991). Finland, therefore, heavily relies on hydropower-based electricity imports from Sweden and Norway.

Nuclear power has been part of the mix since the late 1970s, spurred by the worldwide oil crises of that time. In the 1970s and 1980s, four nuclear reactors were constructed. Half a century later, in 2022, the fifth nuclear reactor, Olkiluoto 3, began operating, but suffered from technical difficulties, limiting production, so only began full operation in 2023, about fifteen years behind the initial schedule. Attitudes to nuclear power have varied over time. The pronuclear group has aimed to depoliticize nuclear power with argumentation about technical safety, while the antinuclear camp has aimed to make the issue more political (Ylönen et al., Reference Ylönen, Litmanen, Kojo and Lindell2017), raising nontechnical questions related to nuclear power.

Biofuels were important in the early 2000s, especially in the form of black liquor, a byproduct of the forest industry, and later also via the direct use of wood for energy. Besides this, various forms of biofuels and technologies have characterized the development of bioenergy (Kivimaa, Reference Kivimaa, Lafferty and Ruud2008), alongside a battle for the use of wood for different purposes. Bioenergy was initially perceived as “the fossil-free source” for Finland, but it became more contentious when wood energy’s real impacts on greenhouse gas emissions and on carbon sinks became more widely considered in the EU. Increasing concern has been placed on the reducing carbon sink of the forests when the use of wood has increased.

The year 2013 was described as the time when the wind power niche began taking off in Finland (Haukkala, Reference Haukkala2018). Wind power has developed rapidly since 2014, contributing almost 12,000 gigawatt hours and 14 percent of electricity consumption in 2022 (Finland’s Wind Power Association, 2023). The capacity in 2022 was circa 5,677 megawatts (MW), with further 44,000 MW land-based and 10,000 MW offshore wind power structures planned (Finland’s Wind Power Association, 2022).

Another dominant feature of the Finnish energy regime is the district heating system initiated in the 1950s that covers about a half of Finland’s residential and service buildings, and is closer to 90 percent in cities (Schönach, Reference Schönach2021). However, this is partly being replaced by an expansion of ground-source and air-source heat pumps as more sustainable heating sources than hydrocarbon and biomass-powered district heating. The expansion is taking place especially in detached housing stock, while for larger buildings district heating still dominates. The district heating system is seen as an important means of energy storage, especially considering the shifts currently taking place toward the advancement of electrification.

Fortum, a partially government-owned company, is the largest provider of heat and power. It had heavily expanded into Russia prior to 2022 and it owned part of the German Uniper corporation before Uniper’s economic difficulties in the same year and until the German government bought Fortum’s share of Uniper. The second-largest energy company is Helsinki Energy, operating in the capital region and owned by the city of Helsinki. The manufacturing industry-owned PVO and the Swedish energy company Vattenfall are the third- and fourth-largest energy sellers.