Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Series Editors’ Preface

- Dedication

- Introduction

- 1 ‘Living modernly's living quickly’: Towards Travelling Light

- 2 ‘A purse of her own’: Women and Carriage

- 3 ‘No one is safe from the beggar's pack’: Portability and Precarity

- 4 ‘Have you anything to declare?’: Portable Selves on Trial

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

2 - ‘A purse of her own’: Women and Carriage

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 December 2017

- Frontmatter

- Contents

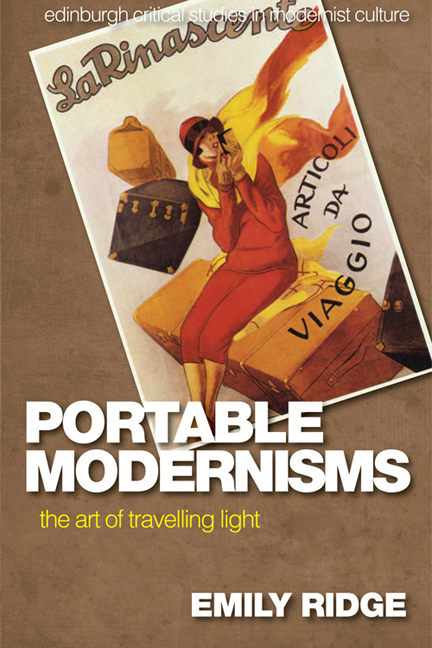

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Series Editors’ Preface

- Dedication

- Introduction

- 1 ‘Living modernly's living quickly’: Towards Travelling Light

- 2 ‘A purse of her own’: Women and Carriage

- 3 ‘No one is safe from the beggar's pack’: Portability and Precarity

- 4 ‘Have you anything to declare?’: Portable Selves on Trial

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

And then Mrs Brown faced the dreadful revelation. She took her heroic decision. Early, before dawn, she packed her bag and carried it herself to the station. She would not let Smith touch it. She was wounded in her pride, unmoored from her anchorage; she came of gentlefolks who kept servants – but details could wait. The important thing was to realize her character, to steep oneself in her atmosphere. I had no time to explain why I felt it somewhat tragic, heroic, yet with a dash of the flighty, and fantastic, before the train stopped, and I watched her disappear, carrying her bag, into the vast blazing station. She looked very small, very tenacious; at once very frail and very heroic. And I have never seen her again, and I shall never know what became of her.

‘[D]etails could wait’, Virginia Woolf interjects in the culminating image of her version of the Mrs Brown story, as recounted in her well-known 1923 essay on the subject of character in fiction. She immediately adds that ‘the story ends without any point to it’. However, she does pointedly draw attention to one particular detail: the fact that Mrs Brown carries her own bag. It is a fact she states twice in quick succession, though it is a detail tellingly overlooked by her imagined Edwardian literary counterparts, in the versions of Mrs Brown respectively allotted to each. Why is this detail worth repeating, while others can wait? Why does Woolf stress Mrs Brown's adamant refusal to let Mr Smith touch her bag, and what does this gesture imply? Why is it something only she purports to notice? And since this is, to all intents and purposes, a discussion of the changing approach to fictional character, and thus to fiction itself, in the early twentieth century, what does this particular detail add to that particular discussion?

This chapter contends that the woman's bag became a central symbolic point of focus and literary motif in portrayals of shifting gender relations during the modern period, dating back to the emergence of literature by and about ‘New Women’ at the fin de siècle. Chapter 1 showed that the ‘Woman Question’ and the thorny issue of women's desires persistently surface as key contributing factors in the declining relevance of the house in the earlytwentieth- century literary imagination.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Portable ModernismsThe Art of Travelling Light, pp. 66 - 107Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2017