Book contents

- The Kingdom of Darkness

- The Kingdom of Darkness

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Preface

- Abbreviations and Conventions

- General Prologue

- Part I Giving Up Philosophy

- Part II Pierre Bayle and the Emancipation of Religion from Philosophy

- Part III Isaac Newton and the Emancipation of Natural Philosophy from Metaphysics

- Part IV The European System of Knowledge, c.1700 and Beyond

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

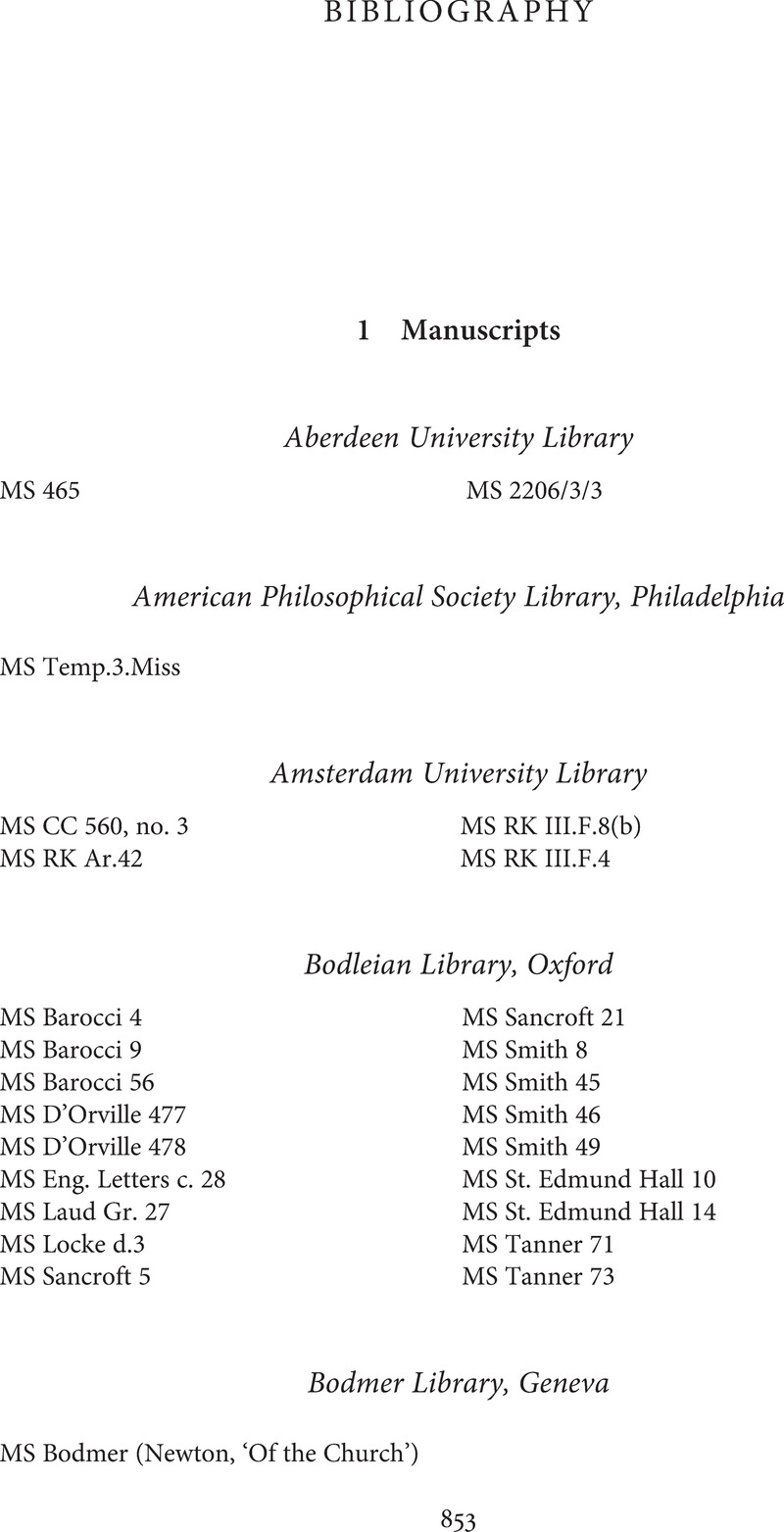

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 March 2022

- The Kingdom of Darkness

- The Kingdom of Darkness

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Preface

- Abbreviations and Conventions

- General Prologue

- Part I Giving Up Philosophy

- Part II Pierre Bayle and the Emancipation of Religion from Philosophy

- Part III Isaac Newton and the Emancipation of Natural Philosophy from Metaphysics

- Part IV The European System of Knowledge, c.1700 and Beyond

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Kingdom of DarknessBayle, Newton, and the Emancipation of the European Mind from Philosophy, pp. 853 - 934Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022