Coming and Going

The most comprehensive local gazetteer about the early history of Fujian, Sanshan zhi (1174–89), records that there are many islands in the northeast sea of Lianjiang County, among which are “the Upper and Lower Gantang in the sea.”1 Upper Gantang and Lower Gantang are the old names of Nangan and Beigan, the major islands of Matsu. A later record explains the origin of the name: “Gantang … was named for its abundance of cogon grass (maogan).”2 A stele standing in Dawang Temple, Tieban Village, Nangan, further reveals the ancients’ footprints on the island. The inscription reads: “Lin Youcai happily donated twenty guan of Zhongtong paper notes.” Zhongtong paper notes were issued during the reign of Kablai Khan (1260–87). By the early years of the thirteenth century, therefore, fishermen were already docking their boats in Nangan and building a temple there.

When Japanese pirates became rampant along the coast in the early Ming period, the government adopted a scorched-earth policy as its coastal defense strategy. In 1387 (Hongwu 20), all the islanders were moved back to the mainland, leaving the Matsu Islands deserted.3 The storytellers’ memories help us to track this large-scale movement of population. According to Chen Jinmei, a storyteller in Shanlong, Nangan, it was said that there once lived a family with the surname Sun and the village was thus once called “Sunlong.” Later, when Japanese pirates went on the rampage, the Ming emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang, ordered all the people evacuated and had the whole village burnt down, turning it into a barren wasteland (J. Liu Reference Liu1996b).

Despite an official edict that “not a single ship should sail the seas,” coastal residents began to revisit Matsu for fishing or resettlement by the mid-Ming. At that time, there were already thirteen settlements in Nangan and Beigan. An important gazetteer, Bamin tongzhi (1490), records:

The Upper Gantang Mountain in the sea has winding and twisting peaks and ridges, on which are six ports including Zhuhu and Huwei. The Lower Gantang Mountain protruding from the sea stands opposite the Upper Gantang Mountain; it has a steep, tall shape and has thereon seven ports including Baisha and Jingcheng. … In Hongwu 20, to defend against Japanese pirates, all the people were moved [inland] near the city.4

Yet in the early Qing years, the residents of Matsu were once again ordered to move: To wipe out the anti-Qing forces led by Koxinga (Zheng Chenggong), the Qing government issued the Great Clearance Order. In 1661, the coastal residents in Fujian, Zhejiang and Guangdong were forced to move 30 li inland:5

South Gantang and North Gantang are in the northeast seas of the county, with a distance of eighty li from each other; both are on strategic locations and have military posts. South Gantang belongs to Min County, and North Gantang to Lianjiang. Beacon towers and watchtowers have been established on North Gantang, where there are … seven ports. …In the early Ming the people were moved inland. The ban on dwelling in coastal areas was later lifted, and agricultural and fishing activities flourished. But when our country was newly established, the rebellious forces in the sea were yet to be pacified, so the people were moved inland again.6

After that year, Matsu was abandoned once again (S. Li Reference Li2006: 75). In 1683 (Kangxi 22), following the pacification of Taiwan, the Qing government gradually lifted the sea ban, allowing the coastal residents to return to their homeland. Nonetheless, it was still forbidden to move to the coastal islands, or to fish or build shelters there. Nangan and Beigan remained “deserted islands in the sea.”7 It wasn’t until the reign of Qianlong (1735–96) that coastal residents gradually started to colonize the islands. Fishermen went there to “build shelters and to hang fishing nets” (daliao guawang), and the number of settlers steadily multiplied (131). This, however, disturbed the officials: “It is inevitable that some tricky fishermen would build shelters or erect poles to hang fishing nets. … But it is reported that there are even people who live there permanently, who gather crowds to cultivate the land and the mountains, and who disobey expulsion orders.”8

Faced with this trend, some officials in Zhejiang and Fujian (such as the Zhejiang Commissioner, Gu Xuechao, 1721–?) worried that the people on the outlying islands would become outlaws and thus suggested burning down the illegal thatch settlements that had been stealthily built over time. Others (such as the Viceroy of Zhejiang-Fujian, Gioroi Ulana, 1739–1795) feared that if all the people of the numerous islands along the coasts of Zhejiang and Fujian were expelled, they would be out of work and might even be forced to turn to banditry. Gioroi Ulana suggested that those people who were already incorporated in the baojia (household registration system) should not be expelled, while other scattered households and those living on forbidden lands should be returned to their domicile of origin and their shelters burned. As for fishermen sailing to the islands and building temporary shelters, the local officials should go and inspect them and issue licenses as appropriate.9

As habitation of the southeastern outlying islands had been debated for a long time, Emperor Qianlong finally decided to legalize it. The imperial decree in 1790 (Qianlong 55) proclaimed that the coastal residents had lived and worked in peace and contentment on the islands for a long time; if they were suddenly ordered to move, hundreds of thousands of people along the coasts might be put out of work, and so they were deserving of sympathy. Besides, if the local officials handled this matter improperly, they would disrupt people’s lives and might even cause them to become vagrants or pirates, a most unsatisfactory outcome. The emperor thus ordered that people on the outlying islands should be allowed to live there without fear of expulsion, with the exception of areas classified as forbidden lands. As for the scattered households, most of them were impoverished, and it was wrong to dash the hopes of such people. In the end, the emperor decreed the following:

The fishermen sail the seas to fish; it is improper to comprehensively forbid them from setting up temporary shelters on the islands. In addition, since there are only a few households, it is not difficult to perform an inspection. …Thus people shall be allowed to live on these islands, and their houses need not be burnt.10

From then on, it was no longer illegal to stay on the islands, and the number of people there gradually increased.

From the mid-Qing to the late Qing, a steady stream of coastal inhabitants of Lianjiang, Changle and other counties moved to Matsu. Yet the residents still traveled back and forth between mainland China and the islands. Previous studies on Taiwan have shown a close relationship between temple construction and settlement formation (See 1973; C. Hsu Reference Hsu1973). The temples in Nangan were mostly built during the Daoguang years (1820–50) in the late Qing (H. Wang Reference Wang2000); the Matsu residents probably settled there in this period. By the early twentieth century, there were already more than 300 households in Tieban, Nangan.11

As isolated and peripheral islands, the historical literature about Matsu is very limited, and descriptions are even rarer. However, the few extant entries disclose again and again the fact that Matsu had historically been a forbidden outpost. Located in the southeast seas of China, Matsu was inevitably under the sway of the constantly changing frontier policies of the government. The fishermen fluctuated between using the islands as temporary shelters, settling there permanently and deserting the islands when forced to do so.

Signposts in the Sea

As indicated above, historical records of Matsu are scarce. Other documents, such as nautical maps, mark the islands as signposts in the sea and describe how they may serve as places to ride out the tide or to take shelter from the wind before entering Fuzhou, the provincial capital.

Sitting at the mouth of Min River, Nangan, Beigan and Baiquan appear in many ancient nautical charts; Dongyin, Nangan and Beigan are marked in “Zheng He’s Nautical Chart.”12 S. Li (Reference Li2006: 46–7) further indicates how Matsu was one of the stations along the sailing routes frequented by both investiture ships (fengzhou) and tribute ships (gongchuan) during the Ming and Qing periods. Investiture ships were sent from Fuzhou to Ryukyu to confer kingship on its kings, while tribute ships carried tributes back to the court. An early Qing record (1684) states:

The two mountains of Gantang are very close to each other. …Whenever a scout is sent to Tamsui, Keelung, Ryukyu or Japan, he always departs from there and returns to the port. Each time the Japanese pirates arrive at Gantang, they also put down anchor there to gather water.13

Historically, the Matsu Islands harbored ships destined for Fuzhou while they waited for the tide or took shelter from the wind. The role of Matsu as a safe harbor became more prominent when Western forces reached China in the late Qing. After its defeat in the Opium War of 1842, China ratified the Treaty of Nanking with Britain, stipulating the opening of five ports along the southeastern coast of China. To safely navigate the reef-ridden waters, the British Navy sent vessels in 1843 to map the islands and reefs along the coast of eastern China, and to determine their latitude and longitude. The results were published in The China Sea Directory (Reed and King Reference Reed and King1867), offering an overview of the ports on different islands.

The British Navy provided more information about navigation in the sea of Fujian, including entries about Baiquan (now called Juguang), Nangan, and Beigan (S. Li Reference Li2006: 98). An Englishman named Collinson (Reference Collinson1846: 231) indicated that if ships encountered the northeast monsoon before entering Min River, they could dock in the south of Baiquan Island to take shelter from the wind. The British warship HMS Cornwallis was recorded to have anchored there for five days due to a strong monsoon wind. Ships could obtain small amounts of freshwater in Baiquan and hire pilots capable of navigating ships to the Min River during ebb tide. Two ports in Nangan could harbor ships during the northeast and southwest monsoon seasons, respectively, and freshwater was also available in both ports. The south of Beigan also allowed for anchorage, and junks and small fishing boats traveled back and forth between Beigan and the Min River.

Later, in order to help ships identify routes through the reefs, Robert Hart, who served as the Inspector-General of the Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs Service, built two lighthouses on the south and north ends of the Matsu Islands in 1872 and 1904. The Dongju Lighthouse in the south directed boats to safely enter and exit Fuzhou and Mawei, while the Dongyin Lighthouse in the north directed them to sail in and out of Sandu’ao (see Map 1.1).

Map 1.1 The lighthouses in Matsu and the sea routes around them

The two lighthouses stood as signposts to guide boats in the sea of Min. In this period, the Matsu Islands were influenced by the treaty port of Fuzhou: the islanders started to have access to Western ideas and goods. Today, houses including elements of Western styles (F. huang ngiang nah) are still very popular in Matsu. These houses in a mixed style were probably developed by artisans inspired by the foreign houses in Fujian.

Pirates and Bandits

As the Matsu Islands were located at the very border of the state, and there was no formal governance over it, numerous pirates and bandits rose to power one after another. For a long period, the islands along the coast of southeastern China were infested with pirates. On Dongju Island a stele commemorating the defeat of Japanese pirates by a general in the late Ming period (1617) still stands. The notorious pirate Cai Qian (1761–1809), who plundered Zhejiang, Fujian, and Taiwan during the mid-Qing, was active on the Matsu Islands. Historical descriptions show that Cai Qian often hid himself in the seas of North and South Gantang (Beigan and Nangan today). According to a memorandum from Li Diantu ([1738]–1812), the viceroy of Fujian, while the coastal navy was gathering in Gantang to blockade the pirates, all of a sudden, “thirty-something pirate ships sailed out from South Gantang; the navy bombarded and fired at them, chasing them in full force …all the way to the outer sea of Baiquan.”14

Cai Qian exacted taxes from the island fishermen and forced the people to supply freshwater. In addition, Cai built shacks in Beigan, and procured rice, food, and material for ropes to use on ships.15 Even in the present day, many elders can still point out the traces Cai Qian left on Matsu. For example, the Matsu people call Cai Qian “the Sea Emperor” (F. hai huongna) (J. Liu Reference Liu1996c); “Datielu” (lit. the blacksmithing furnace) in Tieban Village was said to be the site where Cai forged his weapons; and the crude cannon originally placed in the Goddess Mazu Temple in Tieban was said to be forged by him as well (Wang, Wang, and He Reference Wang, Wang and He2016: 104). It is said that the four Goddess Mazu temples in Matsu were all built by him (J. Liu Reference Liu1996c); indeed, the name of the islands originated from one of those temples (Y. Yang Reference Yang, Liu, Li and Lin2014: 143–4).

The relationship between the islanders and the pirates was in fact even more complicated. Previous studies on the pirates in southeastern China have shown that the pirates relied on the coastal residents in China or the islanders to supply the necessities of life (Antony Reference Antony2003: 17; Murray Reference Murray1987: 89). The story of the Wheat-Field-Plowing King (F. Lemah Toyuong) told by Chen Ruichen, an elder in Dongyin, reveals more about the ambivalent relationship between the islanders and the pirates:

When the pirate ships were docked in Bei’ao Bay, Cai Qian was suddenly agitated and could not sit or lie down. He stood up and strode to the ship’s wheel. The sky above was completely cloudless, and the strong, powerful south winds blew directly at him; suddenly he spied on Bei’ao Hill a farmer and a large yellow ox plowing a field of immature green wheat shoots. Cai was greatly surprised by this scene and muttered to himself, “a farmer shouldn’t be doing that to unripe wheat—how strange!” So he instantly sent out some men to investigate the matter, ordering them to report back to him as soon as possible.

The men sailed ashore on sampans, but when they climbed the hill, they saw neither the farmer nor any green wheat but spotted instead dozens of giant sails on the remote horizon in the direction of Matsu. It was not the fishing season, so there should not have been so many ships in the sea. The men glanced at one another, knowing from experience that something was wrong. They hurried back to the ship and reported what they saw to Cai Qian. Cai thought it very likely that the navy was coming …so he ordered all his ships to embark at once and flee downwind, escaping a possible disaster.

Because Cai Qian called himself “the Sea Emperor,” Cai ordained the mysterious farmer as “the Wheat-Field-Plowing King” in gratitude for saving his life, and had his statue placed on the left side of Goddess Mazu in Dongyin Temple.

In fact, the fate of Matsu was intertwined with pirates and bandits not only in the Qing Dynasty but also well into the early twentieth century, when the newly formed Nationalist government set up in Beigan the first Gan-Xi Joint Security Office (administering Gantang and Xiyang Islands) in 1934. However, in this time of political instability, the Nationalist government was unable to control the numerous islands in the southeast seas. When the Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937, the Japanese forces quickly came to these islands (although they did not occupy them). The Japanese warships patrolled the ocean, mainly with an eye to preparing an attack on southeastern mainland China. Meanwhile, the Nationalist government deployed troops on both banks of the mouth of Min River to defend the provincial capital of Fuzhou. During the turmoil of war, islands in the southeast seas, such as Matsu, became an ungoverned no-man’s- land where many local despots rose to power one after another, transforming themselves into pirates. Japan bought off the local forces to fight the Chinese, calling them the “Fujian National Salvation Army” (Fujian jiuguojun). Though the pirates and bandits abided by the orders of the East Asia Development Board in Xiamen under the Japanese, they also cooperated covertly with the National Bureau of Investigation and Statistics, profiting from both sides of the conflict.16 As for the pirates themselves, they constantly clashed with each other, seeking every opportunity to drive their opponents away. Up to the present day, legends continue to circulate about the pirates and about the many buildings they left on the islands, such as the pirate house in Beigan (see Fig. 1.1).

This house was built by a particularly menacing bandit in Beigan named Chen Zhongping during his heyday in the 1940s. Hiring masons from mainland China to construct it, Chen also had a secret tunnel dug under the floor to allow him escape when needed. Right before completion, however, with only the floor of the second level unfinished, Chen’s “boss” Lin Yihe was killed by the Japanese and he was forced to become a fugitive. Chen did not have a chance to use the house even for a single day. He was later killed in Nangan (J. Liu Reference Liu2004a).

When I first visited Beigan, I was amused to find my guest house hostess reciting in fluent Fuzhou dialect the following limerick composed by Chen:

| My ancestors moved from Heshang to Beigan, | (tsuluong ouhluong, tshiengky poyh kang) |

And lodged above Qinbi called himself Banshan. | (khyngmiah suong’o, toho puangnang) |

In youth I worked in Yuansheng, buying fish, | (tsoey’ iu tshouhsing, nguongsing kautshiang) |

I lost all my money because of gambling. | (ingui tujieng, suokho kangkang) |

Having no way out, to Nangan did I flee, | (mouhhuah khotaih, tahlouh nangngang) |

Where the Yihe army granted a position to me, | (ngiehuo uilui, hungngo tsokuang) |

raised to a director, to Beigan I transferred | (kuangtso tsuoeing, teusuong poyhkang) |

Whoever hears my title Quanquan gets scared, | (miangho kheingngeing. hungnoeyng tukiang) |

for if I beat you up, a single punch will strike your heart. | (kungnau khatheih, suohthui kau ny singngang) |

I still clearly remember the rather realistic punch she threw in my direction to illustrate the last line!

This limerick was obviously intended to intimidate the local people, but it also briefly accounts for the origin of Chen Zhongping and his rise to power. His ancestors came from Changle, Fujian and settled in a place above the Qinbi Village in Beigan. As a young man, he worked in a store in Qiaozi, trading shrimp and other common low-cost fish. Having lost everything by gambling, he fled to Nangan to seek protection from Lin Yihe, a pirate chief. Later, Chen was assigned to Beigan as a boss, collecting protection money from passing fishing boats and merchant ships. All the people in Beigan were afraid of him, for if they dared to disobey him, they would suffer his wrath and even violence.

Other pirates also often compelled the locals to collect fees for them. For example, Chen Ruichen, the Dongyin elder, recalled his own experience:

In the early 1940s, I was forced by the Peace Salvation Army to become the security head (baozhang) of the Dongyong Security Group. …There were tithing heads (jiazhang) under security heads, and at that time the usual practice went as follows: lots written with words like beds, tables, chairs and quilts were put into a bamboo jar or an iron can; each tithing head drew a lot and “collected” the item specified on the lot from each household.

During the Second World War, many pirates and bandits of this kind dominated the sea along the coast of Fujian. For example, Lin Yihe, who granted Chen Zhongping a position, was an important figure on the Matsu Islands.

The rise of Lin Yihe vividly illustrates how these islands remained “a place outside civilization” (huawai zhi di) during the early twentieth century, where local despots, the Japanese, and various Chinese forces collaborated, competed, and clashed with one another. As noted above, it wasn’t until 1934 that a state institute called the Gan-Xi Joint Security Office was established in Matsu for the very first time, with Wang Xuanyou appointed as its director. Yet in less than two years, Wang was shot dead by Wu Yike, a bandit from Changle, China, who seized the office’s guns. After that, Wu often extorted money and goods in Nangan and Beigan; he even robbed the house of Lin Yihe, by then an important local figure. One day the following year, when Wu sailed out to go plundering, Lin captured him and delivered him to the government of Lianjiang County in China. For his actions, Lin was awarded the position of “police captain” (tanjing) by the county government and made responsible for anti-smuggling operations at sea. Before long, however, Lin himself was listed as wanted by the county government and forced to flee because gangsters in his employ had stolen legally confiscated opium. One day, when a village in Nangan was staging performances for deities, Lin Yihe broke into the Township Office and stole its guns, thereby formally becoming a pirate living on pillage and booty. Lin collected protection fees from fishermen and exacted taxes from passing ships (P. Zhang Reference Zhang2001 and J. Liu 2004b). He also opened an opium shop in Matsu, where opium was sold publicly (J. Lin Reference Li2006).

As previously mentioned, the Japanese bought off the local forces and named them the “Fujian Peace National Salvation Army” (Fujian jiuguojun); Lin Yihe was among their ranks. He was incorporated in 1939 and appointed “the commander of the first road army under the second army group” (Di’er jituan diyi lujun siling), while simultaneously cooperating with the National Bureau of Investigation and Statistics, thus playing both sides. At his peak, he built a munitions factory in Siwei Village, Nangan, and mustered his own private armed force. Later, an unfair division of spoils triggered a conflict between Lin Yihe and Lin Zhen, who was in charge of the army group in Dongju. In 1942, Lin Zhen introduced the forces of Zhang Yizhou from Nanri Island and, conspiring with the Japanese, lured Lin Yihe into the sea to drown him (P. Zhang Reference Zhang2001: 983). After defeating Lin Yihe, Zhang Yizhou renovated the Mazu Temple in Nangan in 1943 and erected a stele in front of the temple as a mark of his victory.

Taking over Lin Yihe’s forces, Zhang Yizhou built his short-lived “Kingdom of the Min Sea (minhai wangchao)” which was headquartered in Nangan and stretched from Xiamen in the south to Zhejiang in the north (C. Zhang Reference Zhang1984: 94). Skillful in dealing with the Japanese, Zhang took good advantage of them:

Whenever the Japanese special agents were sent …to South Gantang, Zhang treated them to feasts and even provided opium and morphine to them. …As for the Japanese on the warships in the sea around Dongju Island, when they reached Baiquan or South Gantang, Zhang also paid due respect to them, so the Japanese didn’t have any worry in the Fujian seas. If the Japanese warships mooring offshore at the mouth of Min River requested freshwater, vegetables or other provisions, Zhang was always responsive, and he also often offered intelligence collected from the mainland to the Japanese. Meanwhile, he used …steamships to smuggle goods banned for export during wartime, such as food, tung oil and timber, to Xiamen and Shanghai …in exchange for cotton yarn, cloth and other materials. After transporting the materials back to the islands, he resold them to the mainland, earning a good return.

Zhang also realized that Matsu was on the route from Hong Kong to Shanghai and was frequented by many merchant ships. With roads often blocked during wartime, the sea routes became highly lucrative. Accordingly,

[Zhang] established a taxation bureau in South Gantang and set up branches on other important islands to collect cargo tax, fishing tax, license tax etc. …Every ship that passed through the sea near Gantang had to apply for a sailing license from the appropriate taxation bureau, and the fishing boats in the sea had to pay fishing taxes.

As the Japanese gradually retreated in 1945, Zhang quickly pivoted and opportunistically pledged support to the Nationalist government, transforming himself into part of its “Fujian Vanguard Army” (Fujian xianqian jun), though he was dismissed soon after his incorporation.

To conclude, we could say that in the early twentieth century Matsu was a stateless society located within a no-man’s-land: ruthless bandits and pirates scrambled for power and profit using physical force and tactical ingenuity and surviving in the crevices between warring Japan and China. On these outlying islands they rose, fell, and vanished in the blink of an eye, fleeting as shadows. As the local saying goes: “He whose fist is strongest takes everything” (F. Tie nëüng kungnaumo tuai, tie noeyng to sieh). Indeed, the Matsu islanders seemed to take this for granted.

Islands Indivisible from the Mainland

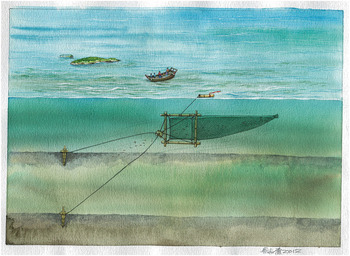

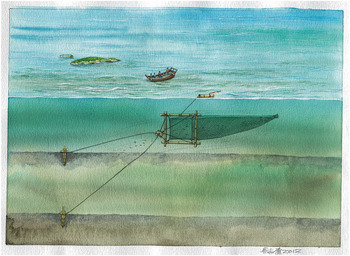

The people who migrated from the coasts of China to Matsu mainly made their living by fishing. They usually chose an area near the sea as a base, and later extended the village inland toward the mountains (see Fig. 1.2).

Fishing was a man’s job and the only source of family income. When men sailed out, they spent all day or sometimes many days at sea, and so the management of the household fell solely on women who were responsible for chores such as cultivating sweet potatoes, cutting firewood for fuel, feeding livestock, and taking care of children. Life on the sea was unpredictable and dangerous and the threat of disaster loomed large; shipwrecks were relatively common. When a fisherman did not return, the entire responsibility for the family fell on the shoulders of his widow. There is a saying in Matsu to the effect that “a wife (or a mother) is a bucket hoop (F. Lauma/ nuongne sei thoeyngkhu).” The analogy drawn between a bucket hoop that encircles the bucket to prevent the staves from falling apart and the role of a mother who holds the family together, protecting the children from destitution, is an apt one.17 If only one family member is to survive most “would rather that the mother lives” (F. gangnguong si nuongma, me a si nuongne). Nonetheless, the hardships endured by widowed mothers and fatherless children were almost unbearable in these barren islands, and thus the Matsu people also practiced a special kind of marriage arrangement in which a man came into the family of a widow (F. suongmuong). His responsibility was to support the family and to take care of the children left by the deceased husband. This allowed the children to receive good care, instead of becoming “a burden as children-in-law” (tuoyou ping). The rewards flowed both ways: the man entering a widow’s family earned respect for looking after her children, and the family’s continuation was guaranteed.

As for the inter-household relationships, people who had lineage relations or came from the same place usually formed their own communities inside the village. Those who came to Matsu alone would ally with people with similar circumstances into multi-surname dwelling units. In Ox Horn, for example, there are five major neighborhood units, including Da’ao (F. toey o, Big Inlet), Niujiaopi (F. ngu oyh biah, Ox Horn Slope), Xibianshan (F. se bieng nang, Western Hill), Nanguan (F. nang nguang, Southerner’s Place), and Liujianpai (F. loeyh kang be, Line of Six Houses). Not only do the residents of each of these units have diverse hometown origins, but they also worship their own separate deities. Before the communal temple was built in 2008 (discussed in Chapter 8), they organized separate ceremonies on festival days. Take, for example, the Lantern Festival (F. pe mang), which is the most important local celebration. Each unit observed it on a different day; thus the same festival was celebrated as many as eleven times in a village! Even though both banks of the inlet in Ox Horn had jointly built a temple for a deity named “Big Brother Chen” (F. ting noey o), each area still chose a different time (during the Dragon Boat Festival and the Mid-Autumn Festival, respectively) to hold the ceremony. In other words, although the villagers of Ox Horn lived together around the inlet, they were not integrated into a community in this period.

Inter-village interactions were limited too. The islanders usually sold fish directly to the mainland in exchange for daily necessities, but there were few inter-village exchanges inside the islands. The islanders seldom visited other villages except to see relatives, and the roads between villages were merely narrow trails overgrown with grass. The Matsu people called the act of going to another village “traversing a mountain” (F. kuo lang), a phrase which clearly illustrates the inconvenience of movement. A good number of Matsu people mentioned that “it was faster to row a boat” to a neighboring village.

During this period, the residents of the Matsu Islands formed an indivisible whole with their hometowns on the mainland. Indeed, the islanders usually replicated their hometown lineage relations on the islands. For example, of the Cao lineage members in Ox Horn, only the fourth and seventh branches lived in the village; the descendants of the eighth branch were isolated on the other side of the mountain, near the islet of Huangguanyu, lying to the east of Nangan. Not until their shabby thatched huts were burned in an accidental fire were they allowed by the other lineage members to move into Ox Horn. This spatial allocation in Ox Horn reflected the relationships of the Cao lineage in their homeland, Caozhu Village in Fujian. It is said that the founding ancestor of the Cao only had seven sons. The eighth branch comprised the descendants of a long-term farm laborer who was considered to be “of impure ancestry” by the other lineage members. When members of the fourth, seventh, and eighth branches moved to Ox Horn, the Cao people still isolated the descendants of the last branch away from the village as before. This spatial distribution reveals how the early society in Matsu duplicated social relations in the mainland.

Between the islands themselves, there were also linkages based on the relations radiating from the hometown. After moving to Matsu, lineage members still kept in close contact with one another even when they were on different islands. For example, the Caos in Ox Horn were the descendants of the seventh branch Cao lineage in Caozhu, Changle. Some of the members of the seventh branch had also moved to Fuzheng Village in Dongju. In earlier days, these Cao lineage members scattered across different islands even bought boats together. Some Ox Horn people said their parents would, on their deathbeds, urge them in particular to keep up close contact with their relatives on other islands.

Similarly, if lineage members moved to different villages on the same island, their relationships would be even closer. For example, there are two lineages with the surname Chen in Shanlong, the largest village in Nangan. Though both Chens came from Changle, China, one belonged to the Chen lineage of Wenshi (hereafter Wenshi Chen), and the other to the Chen lineage of Lingnan (hereafter Lingnan Chen). The ancestors of the Wenshi Chen originally came from Jiangtian, Changle; some of them later moved to Nangan, and they developed into an important group in Shanlong. There are fewer Lingnan Chen than Wenshi Chen in Shanlong itself, but this is not the case when we take the whole of Nangan Island into consideration: in addition to Shanlong, the Lingnan Chen moved to the villages of Tieban and Meishi. Indeed, if the Lingnan Chen united their members in all three villages, they would outnumber the Wenshi Chen and become the biggest group. Liu Jiaguo, a local historian of Matsu, has recorded a dispute in 1930 between the Wenshi Chen and Lingnan Chen which expanded to the other villages in Nangan, and eventually their hometown—Changle, Fujian:

In Shanlong Village, Chen Guanbao of the Wenshi Chen had an argument with Chen Zhengzheng of Lingnan Chen. The family of Chen Guanbao ran a cargo business that made a lot of money. Chen Guanbao, well-fed and corpulent, gave Chen Zhengzheng a good beating. Later, one time when Chen Guanbao was passing by Meishi, he had the misfortune of falling into the hands of the Lingnan Chen. He was kidnapped to the mainland and was being transported to Lingnan to suffer some extralegal penalty. The group who escorted Chen Guanbao, however, was discovered by the Chens of Jiangtian (Jiangtian being the ancestral residence of the Wenshi Chen) at an inlet in Changle, and Chen Guanbao was released through mediation. After this incident, in order to empower the lineage members on the outlying islands, the Chens of Jiangtian even “opened the ancestral hall (F. khui sydoung)” and carried a palanquin to Lingnan. They demanded that the Lingnan Chen stop bullying the Wenshi Chen on the outlying islands; otherwise, they would “fight the whole village” (F. piang tshoung) of Lingnan regardless of cost.

This story shows how the Matsu Islands and the relevant mainland hometowns were an indivisible whole during this period. Though geographically separated by the ocean, they shared a strong social and cultural affinity. Indeed, the Matsu people say that in the past, traveling to Matsu was described as “going to the outer mountain (F. kho ngie lang),” while departing for the mainland was called “returning home (F. tuong tshuo li).” At that time, people on Matsu would try to return home to celebrate important festivals. Since the location of Ox Horn is very close to the mainland, the villagers always held festivals one day early so that the residents could return to their hometowns in time for the celebrations there. This special custom continues to the present day, but the residents of Ox Horn are now teased by their neighbors as “real foodies (F. tshui ia ie),” who just cannot resist feasting twice for the festival. Last but not least, when islanders reached the end of their lives, some hoped to be brought back to their hometown for a proper burial. As a result, there was a practice of the “waiting coffin (F. ting nuo).” The bereaved set up a shelter outside the village and temporarily placed the coffin on a wooden rack or on a stone to wait for the ship to take the coffin back to the mainland for burial.

Conclusion: Stateless, Transient, and Fragmented Islands

When I first visited Matsu in 2007, I was surprised to find that unlike in Taiwan or southern China, there are no lineage halls on the islands. It wasn’t until I visited an old house and heard an eighty-year-old woman’s explanation that I understood the reason for this. The ancestral altar in this lady’s old house looks very rough and rudimentary (Fig 1.3): when her family built the house, they simply dug a hole in the corner of a wall to place ancestral tablets or pictures. The tablets are often surrounded by a messy collection of objects and appear to lack the aura of sanctity that we commonly see in Taiwan.19 I asked her why this was so. She replied that the Matsu people did not intend to stay on the island permanently; they lived simply and remained flexible in life, ready to return to the mainland at any time.

Indeed, people who relocated to Matsu in earlier times often moved back and forth between their hometowns and the islands according to the fishing season. As they did not necessarily plan for a long-term settlement, the relationships between the lineage members in Matsu were not as stable as those in their hometown. The lack of a lineage hall or relevant ceremonies further reduced the cohesion among the members on the islands. Cao Changbi, the editor of the genealogy of the Cao family in Ox Horn, spent more than two decades going back and forth across the Strait for his laborious investigations.20 Cao told me that the greatest difficulty he encountered while compiling his book was a frequent lack of links between the lineage members: many people only vaguely know that they are descended from a common ancestor but are unable to trace genealogical relationships in detail. His difficulty gives further clues as to why there are no lineage halls on the islands. Since the islands for them were but “outer mountains,” the Matsu people thought it unnecessary to build a lineage hall in a temporary residence. Neither did they hold any big celebrations on the islands or pilgrimages to China in the early days, since they could return to the mainland at any time.

In sum, Matsu in early times was not even an immigrant society but merely a stopover or temporary place to live, with people coming and going in a constant state of flux. Lying beyond the reaches of state power, the islands were almost deserted, a lawless place where “the strongest fist took everything.” The island society during this period was characterized by transience and brokenness. All of that changed with the arrival of the army in 1949.

Memories of a Murder

One evening around dusk, the company commander of military base 99, located just above Ox Horn, caught sight of Guoxing—a soldier from Jinmen who had been transferred to the Matsu Distillery in the village—heading toward the house of his lover Xuemei. The company commander immediately grabbed his bayonet and strode toward the village.

Xuemei was an attractive woman. She had been dating the company commander for a while when she also began to get close to Guoxing, who frequently went to her house to chat and flirt. The commander had seen him heading there many times and suspected that the two were having an illicit affair. It was around five o’clock that evening, and the commander had already planned what he would do. Watching Guoxing go into her house, he armed himself and hurried straight there.

He barged into the house and attacked Guoxing with his bayonet in a rage. Although badly wounded, Guoxing managed to escape in the confusion. The commander did not bother to follow him. Instead, he turned his attention to Xuemei, forcing her into a corner and stabbing her dozens of times until she collapsed dead in a pool of blood.

Having murdered Xuemei, the commander left the house to find Guoxing. He did not give chase, but rather stood near the doorway of Xuemei’s house and kept watch. He knew the layout of the village so well that there was nowhere Guoxing could escape him.

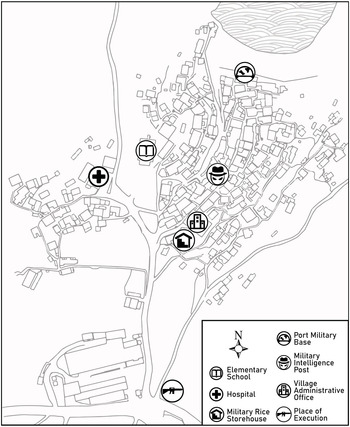

Bleeding and desperate, Guoxing fled down to the bay to try to find shelter with the soldiers at the Port Military Base, screaming, “Help me! Help me!” But the soldiers had no orders from above and did not know who he was, so they warned him away as he approached. When Guoxing saw that they had no intention of protecting him, he headed back across the village. He passed the central state school to the county hospital, looking for someone to help him. But since it was after five o’clock, the hospital was closed, and the military doctors and nurses had gone home.

Guoxing had no choice but to turn in another direction, likely heading toward the village administrative office. His shrill screams for help carried throughout the village, but no one dared to come out and aid him. The company commander heard him and headed toward his voice. A little past the rice storehouse, he caught up with Guoxing and repeatedly stabbed him in the back. Guoxing collapsed and died beside the fishing nets outside a villager’s house. Then the company commander calmly left the village and returned to the military barracks without so much as a backward glance.

The day after these events occurred, the commander was arrested at military base 99. Because the circumstances involved not only the taking of two lives, but also the highest-ranking official on the island ever to be implicated in a crime, the news had risen through the lines of command to the very top. The judgment came quickly, and announcements of the time and place of the execution were posted all over the island.

Early on the day of the execution, the commander’s hands were bound and a wooden tablet stating his crimes was fastened to his back. He was made to stand in the back of a military truck and was driven from village to village as a warning to the public. Finally, he was taken to the execution site near the entrance to Ox Horn. Many villagers, even those who were just primary school students at the time, witnessed the execution. “Although terrified, we were curious to see what would happen,” they said. Their descriptions of the execution are particularly striking:

Across from the execution site was a hill covered with military police. They all carried guns—it was scary!

The military commander was pulled off the truck and made to kneel at the foot of the hill.

They offered him some food. He didn’t eat anything, but he drank the sorghum liquor they gave him.

After that, the placard on his back was taken off and thrown to the ground. It was time for the execution.

Six executioners lined up in a row with their guns pointed at his head. In fact, only one of them was going to shoot, but they wanted a show of force.

Before he was killed, the company commander let out a shout, something like “Long live the Republic of China!” or some such patriotic motto.

Everyone fell so silent that it was as though we could hear each other’s hearts beating.

Bang! Bang! Bang! There were three shots in a row, but the commander didn’t fall. He wasn’t dead! According to the custom, if three shots didn’t kill the criminal, it meant he wasn’t destined to die. But because the circumstances involved someone so high up, the higher-ups at the WZA had already made their wishes known: “He must die!” So they shot him once again.

I heard his last sigh…oh!…and he was gone.

Cao Daming, an Ox Horn villager who at the time was barely fifteen years old, later helped the deputy head of the village investigate the case and so could describe the events vividly even forty years later. Others remembered the case clearly because they had witnessed the execution. This event gives us an important perspective on the reign of the military in Matsu. How was military rule imposed on the islands? How were the people governed? In a place which had never been directly governed by a state power before, how did the locals conceptualize the military state?

The Advent of the Military State

When Chiang Kai-shek’s army suffered successive losses against the CCP (Chinese Communist Party), his government withdrew to Taiwan in 1949, while the KMT (Kuomintang, Nationalist Party) armed forces retreated to the islands along the coast of southeastern China. In 1949, Chiang’s army reached Matsu, and in 1950 they set up the Matsu Administrative Office (Matsu xingzheng gongshu) with jurisdiction over the archipelago of Matsu and the islands to the north. After the northern islands fell into enemy hands in 1953, the KMT government set up three county administrative offices in Fujian—Lianjiang, Changle, and Luoyuan—on the islands of Nangan, Xiju, and Dongyin, to symbolize that Chiang Kai-shek still governed Fujian province, and therefore more generally the rest of China.

Simultaneously, the KMT established the East China Sea Fleet (Donghai budui), which included fishermen from coastal Fujian, pirates (such as the aforementioned Zhang Yizhou and the former “National Salvation Army”) (Donghai shilu bianzhuan weiyuanhui 1998: 97), and soldiers stationed at Xiju by the mouth of the Min River, who were posed to launch guerrilla warfare at any moment. Since the KMT government offered almost no provisions at that time, the soldiers behaved much like the bandits of the past, plundering shipping vessels to survive (226–8). With the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, the United States established Western Enterprises Inc. (Xifang gongsi) in Taiwan in 1951, a Western outfit that was designed to spy on the enemy and to carry out guerrilla warfare in order to contain the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) military strength and to prevent it from dispatching forces along the southeastern coasts to fight on the Korean peninsula. The company operated under the auspices of the CIA and established a liaison station in Xiju, collaborating with the East China Sea Fleet in attacks on coastal China (Holober Reference Holober1999). The company closed down when the hostilities ended, and the East China Sea Fleet was absorbed into the KMT armed forces in 1955. Although the USA Military Assistance and Advisory Group still maintained a base in Nangang, they withdrew completely in the 1970s.1

After repeated losses in the series of battles between the KMT and the CCP on the southeastern islands, the KMT government was left holding control over only two island areas, Jinmen and Matsu. With no end in sight to the standoff between the KMT and the CCP, Chiang Kai-shek implemented military rule over the frontlines of Jinmen and Matsu in 1956. The Warzone Administration (hereafter WZA) was a centralized military administration, subordinating civilian affairs to the military command. It took centralized orders from the highest military commanding officer on the islands, unifying the whole society and the lives of citizens under military rule (Guofangbu shizheng bianyiju 1996: 96, 109). It was originally employed during the war to govern occupied territories and newly recaptured territories, and it was designed to control manpower and resources within military zones for the benefit of the military (8, 101). Since Jinmen and Matsu were on the frontlines of the conflict between China and Taiwan throughout the 1950s, Chiang Kai-shek chose these two areas as a “testing ground” for military administration.

From the point of view of the government, over the short run the implementation of the WZA in Jinmen and Matsu could provide a protective screen across the Taiwan Strait. In the long run, it was hoped that political, economic and cultural development of these warzone areas would be carried out under military control. With the ideal “to administer, instruct, enrich, and secure” (guan, jiao, wei, yang) (190), the military army aimed to transform Jinmen and Matsu into “a model county for the Three People’s Principles” (sanmin zhuyi mofan xian) in the Republic of China.

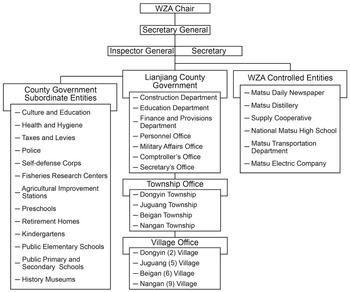

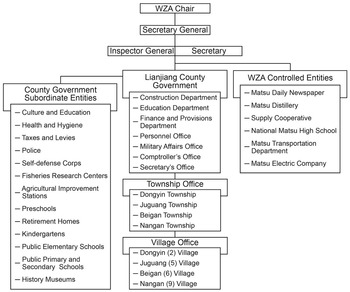

The WZA was led by the committee chair, held by the islands’ highest commanding officer, with a secretary-general under him, held by the director of the Office of Political Warfare. The Warzone Administration Committee (WZAC) consisted of five to seven members and had jurisdiction over the Liangjiang county government. On the premise that the military would govern civil affairs, the WZAC was responsible for governmental policies and supervision, while the county government was responsible for the planning and implementation of those policies (Fig. 2.1).

Fig. 2.1 Matsu Warzone Administration Organization

In addition to WZA organs, the military had other ways of managing the villages. Each village head was selected by the WZA, and a deputy village head (also known as a political instructor) was sent by the military to supervise and oversee village affairs. The military also had a hand in the lives of individuals: locals were armed and organized into civil defense units. Every man between the ages of 18 and 45 and every woman between the ages of 16 and 35 had to participate in four weeks of training twice a year.2

From the above description, we can see that the WZA produced a system in which the military had full command of the local people and their resources. It was, first and foremost, a systematic administrative system commanded by the military. Second, it reorganized the people into civil defense units to assist in the war effort. Third, it controlled the resources of the islands with the establishment of the “Supply Cooperative” (1953) and the Matsu Distillery (1956), which brought the consumption and circulation of goods under government management. Finally, the military state also published a local newspaper, Matsu Daily (starting in 1957), to promulgate government orders and enforce ideological control. Overall, the WZA or military governance represented a kind of militarized modernism (Moon Reference Moon2005; Szonyi Reference Szonyi2008): power plants, water reservoirs, hospitals, and schools were set up on each island. Many modernizing projects of farming, forestry, fishery, and animal husbandry were implemented to make the best use of the people and resources within the warzone.

The establishment of this particular administration had its own historical basis and objectives. Szonyi’s (Reference Szonyi2008) research on Jinmen builds on the geopolitics of the Cold War and greatly clarifies the significance of Jinmen and Matsu with respect to America, Taiwan, and China. When the Korean War broke out, the American president Harry Truman declared a “neutralization of the Straits of Formosa” in order to cool hostilities between China and Taiwan. In 1958, America and Taiwan signed the “ROC-US Mutual Defense Treaty” to work together to prevent the spread of communism, but the treaty did not extend to Jinmen and Matsu. In 1979, when the US and China established diplomatic relations, America abrogated its mutual defense treaty with Taiwan. Although America agreed to sign the “Taiwan Relations Act” to help Taiwan to protect itself and to consolidate its East Asian line of defense in the Cold War, the position of Jinmen and Matsu was left unclear.

For Chiang Kai-shek, Jinmen and Matsu had great significance. Located in the southwest and northwest parts of the Taiwan Strait, they could block Taiwan’s access to Xiamen, Fuzhou, and Sandu’ao (Guofangbu shizheng bianyiju 1996: 193). The islands were also of military importance in other ways. They allowed outposts of soldiers to carry out intelligence gathering and guerrilla warfare, as well as preparation for PRC counterattacks. Because they were so close to mainland China and had once belonged to Fujian province, their very existence as such could be claimed as evidence that Chiang Kai-shek was still in control of “China” (and not just of Taiwan). Chiang Kai-shek also believed that the strategic importance of Jinmen and Matsu could actually ensure America’s continuing support for Taiwan (Szonyi Reference Szonyi2008: 43). It was for these reasons that Chiang tried to construct an image of Jinmen and Matsu as symbols of a global fight against communism.

In China, Mao Zedong considered seizing Jinmen and Matsu. However,

…by September [1958] Mao was confirmed in his decision that it would be counterproductive for Jinmen to fall to the PLA. The ROC presence on Jinmen was a reminder that both regimes agreed there was only “One China” that would one day be reunified. If Jinmen were to fall, it might be a first step toward the permanent separation of the two regimes, toward “Two Chinas.”

Therefore, from 1958 to 1979, when diplomatic relations were established between China and the US, the People’s Liberation Army engaged in a special “one day on, one day off” (danda shuang buda) battle tactic, which allowed the defending forces in Jinmen and Matsu a chance to resupply. This also served to remind the US and Taiwan that both Taiwan and the islands of Jinmen and Matsu belonged to China (76).

“One Island, One Life”

How did the implementation of military rule, and in particular, the WZA, influence Matsu? As previously described, Szonyi’s research on Jinmen, another frontline island of Taiwan, demonstrated how militarization (Lutz Reference Lutz2001, 2004) infiltrated every aspect of Jinmen, and how the local society—whether in terms of the labor force, material goods, minds and bodies—was gradually molded to serve military goals. To understand the effects of military rule on Matsu, it is therefore important to note that it had a very different history from Jinmen before the army arrived. A brief reminder of Matsu’s transient and fragmented past, discussed in detail in Chapter 1, will aid in our discussion.

Matsu before 1949 was a forbidden outpost and a stateless society. The first official administration over the area was established only in 1934; even so, the responsible officer sent to the island was killed by bandits in less than two years. Matsu was quite lawless in the early part of the twentieth century and hostage to violent clashes between pirates, bandits, and warring international forces. Before the arrival of Chiang Kai-shek’s army, there were few links between the villages of the Matsu archipelago; rather, each was connected to Fujian separately. The people at that time were often temporary residents during the fishing season: they described the islands as merely their “outer mountains,” while their real “homes” were on the mainland. Not only were they ready to return “home” at any time, many important rites were performed on the mainland. For this reason, inter-village interactions were limited, and even within each village, different neighborhoods often remained independent from one another.

The establishment of the military administration in Matsu was thus unprecedented and totally transformed the islands. On the one hand, modernizing projects including power plants, reservoirs, fishery and agricultural improvement centers were initiated to augment local production capacities; and a new Matsu currency and the Regulation of Goods Department directed the flow of money and goods. On the other hand, intensive surveillance, including household registration and regulation of people’s movements, as well as normalization, such as schooling and other ideological controls, were implemented at the level of the individual. The islands were thus brought totally and abruptly under military control.

The Matsu archipelago, however, is spread along a stretch of 54 km of ocean. During a war, contact between the islands could be easily cut off. Even more important than developing the labor and resources of Matsu was the need to foster a spirit of independence so that each island could carry on the war effort on its own. When the army arrived, they quickly constructed ring roads on all the islands; military trucks served as means of public transport, running between villages to encourage interactions between locals. Important intersections were festooned with spirited slogans, such as “One island, one life—the army and the people are one family,” to indoctrinate the population and to promote a sense of solidarity (Fig. 2.2). The army also published an island newspaper, Matsu Daily. A shared daily rhythm thus appeared; an idea of simultaneity, provinciality, and even a common fate among the islands had emerged. A new consciousness on each island, and also on the archipelago writ large, had arisen: Matsu had become an imagined community (Anderson Reference Anderson1991[1983]).

Fig. 2.2 A carved slogan erected beside a Matsu transportation hub: “One island, One Life”

The army’s large-scale modernization projects, from the paving of roads and island-wide forestation, to compulsory education, were jarringly new for the people who had long lived on the peripheral margins of the state. Since the Matsu Islands had always served as a temporary residence, the first facilities were rudimentary and shabby. The massive improvements of infrastructure, and the ubiquitous schools in particular, met with the people’s approval, to the extent that to this day they are grateful even today for the army’s contributions to these once-barren lands. Locals and soldiers gradually formed a sense of being “one community.” Although this concept was initially imposed by the army, it penetrated deep into the island’s social texture and the people’s minds.3 During this time, the islanders identified “Matsu” as a place of great military importance, “a springboard against communism” (fangong tiaoban), and “a protective shield across the Taiwan Strait” (taihai baolei), a notion which legitimized military control and justified the many sacrifices made by its people.

A Trail of Blood

Even so, it cannot be denied that the military state was an imposed power, one that was armed with physical and disciplinary force. How did the people of Matsu experience this abrupt intrusion? How exactly did this power weigh on individuals? The memories of the murder love triangle recounted above provides further clues.

The people of Matsu called the soldiers “lang a liang,” meaning “two different voices” in the local dialect, emphasizing the difference of their origins and languages from those of the islanders. The two men involved in the love triangle—the company commander, and Guoxing, who had been transferred there from Jinmen to work in the Matsu Distillery—were both outsiders. The new administration, the WZA, brought in such outsiders and set up institutions that had never before existed in these outlying islands. When locals recounted the event, they usually emphasized how Guoxing turned to different state institutions for help after he was injured: the port authorities, the county hospital, and the village administrative office (Fig. 2.3). This reveals how a once isolated world had by this time become a military state. The institutions Guoxing or the commander passed, such as the military intelligence post and the rice storehouse, had been set up as part of the war effort. These buildings obtruded everywhere in the village as physical manifestations of the intrusion of the military state in every aspect of life.

Fig. 2.3 The buildings and sites related to the crime4

The crime of passion also demonstrates how these state institutions were frequently inhumane and unconcerned with the plight of the local people. When Guoxing ran, dripping with blood, to the port authority to seek help, the soldiers made no attempt to assist him. He could only flee in a panic to the next place of possible aid, namely the army hospital. But since the military personnel there were regular nine-to-five workers, they had already gone home.

This story was narrated to me in detail by Cao Daming, who was fourteen or fifteen years old at the time of the murder. A child of a poor family, he began to work as a messenger boy for the local village office not long after he finished primary school. Encountering this tragic event at an impressionable age, he remembered it vividly, particularly the long trail of blood. The deputy village head was charged with investigating the causes of the murder and reporting back to the army. Cao accompanied him to examine the sites and timeline of the violent acts. That message boy is now over sixty, but he spoke of the events as though they had happened yesterday, becoming agitated and even beginning to stutter. When asked about his speech impediment, he answered that when he was a young boy, his family lived next to a room used for interrogation by the army, which often held “communist spies.” Curious, he would sometimes creep up to the room’s windows with his two brothers to watch the prisoners being tortured for information. He was still young and innocent at that time, and he and his brothers would imitate how the spies talked as they underwent water torture or were beaten:

I – I – I don’t know!

I – I – I really didn’t do it!

It – it – it really wasn’t me!

Even today, he and his brothers still have a slight stutter. The scars left by military rule have not healed.

I heard this story not long after arriving in the village. Startled, I decided to scrutinize how military rule had changed the lived world of the islanders.

Circumscribed Spaces

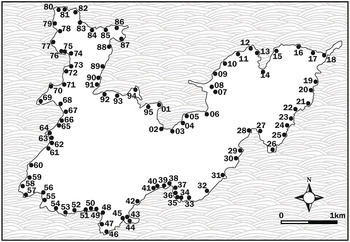

What followed the imposition of military rule was a general sealing off of the islands. The people of Matsu used to be able to move about freely, but soon each island was encircled by military bases. The coastline of Nangan, for example, had ninety-five coastal military bases and checkpoints keeping watch over the open sea (Fig. 2.4).

Each inlet and all of the coastlines had layer upon layer of military defenses. Inlets were fortified with anti-landing spikes and shards of glass, and both sides of promontories were dotted with hillside military blockhouses. This fortification of village inlets (Cheng Reference Chen2010: 74) not only cut the islands off from one another, but also cut the local people off from the ocean. The sea-going Matsu people, who liked to collect shellfish during low tide, now had to pass through layers of wire fencing and landmine zones in order to get to the shore where they then risked being driven away by soldiers. For years, the people of Matsu born during military rule grew up as strangers to the sea. Here’s how Xie Zhaohua, a local doctor, describes his experience as a child:

To me, the sea was always foreign. Though I could see it each morning when I left the house, I always kept my distance from it. It was foreign not because I couldn’t see it, but because there was no way to get close to it. Our teachers told us again and again not to approach the shores, especially areas surrounded by wire fencing, which meant that they were “dangerous landmine zones.” Those were forbidden areas, secret places, just like the many military encampments hidden in the mountains.

In this passage, Xie Zhaohua’s allusion to the “many military encampments hidden in the mountains” is worth examining. The memories of old residents as well as photographs from the period show that in earlier days, trees were very sparse on the islands and hillsides were covered with thick cogon grass. According to records from 1956, “the whole island had only about twenty banyan and other trees, and the bare hills were covered in pale sand” (Fujiansheng lianjiangxianzhi bianzuan weiyuanhui 1986: 471). Thick vegetation, however, could also provide camouflage for military encampments and helped to prevent enemy fire from reaching its target; moreover, military activity could be carried out in secret behind the tree cover. Given this necessity for concealment, the WZA began to carry out continuous “Matsu forestation” projects, implementing measures of “rewards and punishment to promote forestation” (Weihu shumiao 1961). The military at one point even decided that sheep were an impediment to forestation, and promulgated an edict ordering the “elimination of sheep” (Tan lühua 1962). Not content with forbidding the grazing of sheep, the army announced that any sheep found grazing outside the allowed areas could be killed by any person (Y. Li Reference Li1998: 49; B. Yang Reference Yang, Liu, Li and Lin2014: 271–2). Liu Hongwen’s article “Sheep,” describes an incident that occurred at the time between a group of Matsu school children and a sheep:

In those years, you would always see a few sheep around the islands, perching high up on towering ocean cliffs. …Some said that these were sheep that had been driven into the wild after the forestation projects and the prohibition on grazing. Others said that they belonged to noncommissioned officers who were raising them on the sly…. At that time, I was in elementary school, and each day I had to walk with some of my classmates down a mountain path to get to the school. …One day not long after we had left our village…we suddenly saw a frail-looking sheep on the mountainside to our left. It was nibbling at the grass and staring at us forlornly. One of us started shouting “baaaa baaaa”…and it lifted its head to look at us. We…gave the sheep a nickname, “White Whiskers.” Every day we hoped to see White Whiskers again. The bolder ones among us would even pull on White Whiskers’ beard and rub his belly. …Forming a relationship with White Whiskers became the most exciting event of our schooling.

One day we came home from school, and the atmosphere in the village seemed strange. The adults were all silent and mysterious…as though they were hiding something. Then…I went around to the back door of my uncle Jinquan’s house, and my eyes fell on the already-skinned body of a sheep…hanging bare and naked from the doorframe. …It was White Whiskers. In that difficult time of deprivation, especially in a poor remote village on an outer island, a meal of stewed mutton was a very rare pleasure. That night, the whole village was happy, and everyone got a share of the meat and organs. My family got a small portion of a leg. …I had no appetite. All I could think about was why White Whiskers had come down from the mountain. He had trusted us so much that he’d lost his wariness around the villagers. And when the villagers caught sight of him…

After the sheep disappeared, the forestation of Matsu proceeded apace. Today Matsu is completely green, and each island has more than eighty percent forest cover (B. Yang Reference Yang, Liu, Li and Lin2014: 272). However, this also divided the island’s high-altitude areas from its low-altitude areas; the difference between the military encampments concealed in the mountain forests and the exposed villages along the inlets was thrown into stark relief. The history of the development of the villages of Matsu cannot be separated from the fishing economy. The villagers were fishermen and built their houses first around the inlets and then expanded out toward the mountain cliffs. Outside of the villages, the mountains were covered in trees, concealing military bases, blockhouses and encampments. From above, the soldiers stationed in the woods could maintain a clear sense of what was happening in the villages.

Foucault’s (1977) concept of panopticon can help us understand the power dynamics of this spatial arrangement: the Matsu villagers below could not see the soldiers hidden in the mountain forests, but the soldiers above could tell at a glance what was happening in the villagers’ lives, even knowing the comings and goings of any given individual. If we return to the crime of passion and examine it in terms of its location—Ox Horn—we find that there were three nearby encampments placed above the village, from which each household could be seen clearly. In other words, the company commander need only look down from his encampment to apprehend what was going on with his lover and his rival and prepare to ambush them. After Guoxing was stabbed and fled, the company commander knew Ox Horn so well that he could infer the route Guoxing would take to try to escape and felt no need to pursue him. He need only wait at a major intersection for his rival to return exhausted and weakened. The company commander’s gaze in this incident thereby represents the state’s panoptical power. The state could observe every villager, while also remaining invisible to the villagers. As an agent of the state’s panoptical nature, the company commander both created and enacted the state’s potential to see and to know.

If Foucault’s concept of the “panoptical” can help us understand the spatial structure of the military rule over these islands, then the execution following the love triangle murders shows us an example of state ceremony. Geertz (Reference Geertz1980: 123) says that the state draws its force from imaginative energies. From this perspective, it is clear why the state decided to publicly execute the company commander. Indeed, the set up was a carefully staged state ceremony: the company commander forced to wear a placard inscribed with his crimes and paraded around the village, the execution grounds filled with somber military police, the six pointed rifles, and the WZA’s order to shoot to the death. Its goal was to display, defend, and reaffirm the state’s power. Ironically, only the patriotic slogan shouted by the company commander before his death revealed the real executioner behind the scenes.

Sailing through Liminality

As one can imagine, with the islands closed off from the outside world, border-crossing became very difficult. During the military reign, strict controls were imposed on movements between Matsu and Taiwan. The application process to leave was very tedious:

To board a ship, you had to have papers, formally called a “Republic of China Taiwan-Jinmen-Matsu Area Travel Permit.” First you went to a studio to get a headshot taken, then you had to fill out the forms, find a guarantor, and take everything to the village office. Your paperwork was checked at the local police headquarters before finally being sent on to the local command post. Every detail was inspected at each stage, and each step carefully controlled. …Then you had to wait…and when the papers were issued…you had to somehow get a berth on the ship. Sometimes there was space and sometimes there wasn’t. It all depended on what kind of connections you had.

Even after all of the aggravating paperwork, traveling by supply ship was a painful experience shared by nearly all the islanders. At that time, no civil vessels made the trip between Taiwan and Matsu, so Matsu residents heading to Taiwan had to take supply ships. A resident of Dongyin recalls that in the early days, a supply ship could take as long as a week to reach Taiwan: after leaving Dongyin, the ship first went to the administrative center in Nangan, and then headed back north to Beigan before proceeding to Dongju and Xiju. Only after it had circled all of the islands did it finally make its way to Taiwan. Although this detour was later shortened, one still considered oneself fortunate if one could make it to Taiwan within two days.

A long tedious journey was one thing, but what they encountered on the ship was really torturous:

On the day of the trip, we rose at dawn…it was drizzling, and people squatted in rows all along the beach, patiently waiting to be called onboard. The military police shuttled back and forth, checking our papers, ransacking our luggage…they went through everything and left behind a mess.

Finally, we were given the signal to board, and the crowd swarmed toward the mouth of the huge beast [ship], and found berths in the gloomy cabins that were filthy with cement, dust, rice bran, engine oil, and putrefied fruit. Many were left without a berth, and had to find a spot in a corner where they could spread out a mat or put down a piece of cardboard. This was where they would rock back and forth for eighteen hours.

The summer was easier, since people could be aboveboard on the deck…occasionally a wave would come up and slap their faces, and soon their eyes, faces, and arms would be covered in a thin layer of sea salt. Even the breezes were salty. …In the winter, the ocean wind was piercingly cold, and enormous waves would beat the deck while everyone hid in the hull and retched as the children wailed and the filth got worse and worse.

It was just as agonizing to come back to Matsu from Taiwan. Migrants returning to Matsu first had to register at the Jinmen-Matsu Guesthouse (Jinma binguan) in Keelung and then wait. Sometime in the afternoon, if the guesthouse posted a sign saying “Departures Today,” everyone would prepare to board with relief. If no sign was put up, they would have to return the next day. The Jinmen-Matsu Guesthouse was provided for soldiers to have a place to stay on those days when the weather was too poor for the ships to sail. In general, ordinary citizens had to return to their residences each day until they could leave. For young people in particular, who had very little money to begin with, going back and forth a few times would easily exhaust their funds. Cao Daming recounts how he waited once for seven or eight days until he ran out of money and decided to sleep in an empty freight truck parked near the Jinmen-Matsu Guesthouse with his teenage friends. He woke up to realize that the truck was driving south. It turned out to be a vegetable truck from a nearby market, and the driver had stopped to rest before leaving early the next morning to pick up more produce. When the driver realized he had stowaways, he scolded them and shooed them off. The penniless young men could only put their heads together and try to figure out a way to get back to Keelung.

The passage between Matsu and Taiwan was like a liminal period, in which both the body and spirit were tested and transformed. As Turner has stated: “[D]uring the liminal period, neophytes are alternately forced and encouraged to think about their society, their cosmos, and the powers that generate and sustain them. Liminality may be…described as a stage of reflection” (Turner Reference Turner1967: 105, original italics). This kind of reflection happened not only during the journey on the ship, but also became deeply ingrained in people’s memories. The local leaders examined in Part III frequently begin with their painful experiences of such trips when explaining the impetus behind their desire to change Matsu.

Conclusion: Imagined Community vs. Individual Suffering

In 1949, the army abruptly arrived in Matsu and indelibly changed the fate of the islands. This chapter analyzes how military rule transformed the lives of the local people from the perspective of space. I have demonstrated that once the Matsu archipelago became a frontline in the war, the close connections that had previously existed between the islands and the mainland were severed. The WZA carried out large-scale construction projects, propagated public education to modernize the islands, and also employed print media and local currency to create pan-island connections. As a result, “Matsu” became a newly imagined community, with a new social imaginary as a “fortress in the Taiwan Strait” and a “springboard for anticommunism.” This imaginary gradually became the identity of the Matsu people.

If we examine the lives of individuals more closely, however, we see a different picture. The state came from afar and penetrated every aspect of the islands immediately and deeply: all kinds of military institutions (such as port bases, intelligence posts, and rice storehouses) mushroomed, and became integrated into the living spaces of locals. In the hills above the villages were secret military barracks, with their constantly surveilling eyes: the oversight and control of the state was ubiquitous. Anyone wanting to enter or leave the islands had to brave the torture of travel by sea. The crime of passion, Cao Daming’s stutter, the schoolchildren who lost their beloved sheep, and the sense of being close to the sea but estranged from it—all these examples demonstrate how the power of the state permeated people’s bodies, minds, emotions, and knowledge, clashing with them and creating conflicts and trauma.

The impact on individuals and society when a place becomes a frontline is complex and intricate. In Chapter 3, I will explore this issue further from the perspectives of the fishing economy and gender relations.

In descriptions of the love triangle murders, Xuemei’s husband never puts in an appearance. When I asked about him, the answers I got from residents of Ox Horn were always vague and ran along the lines of: “He was a fisherman”; “The fishing in Matsu wasn’t good, so he moved to Keelung (Taiwan).” Is the absence and silence of this fisherman husband connected in any way to the difficulties of the military period in Matsu?

Restricted Fishing and Imagination

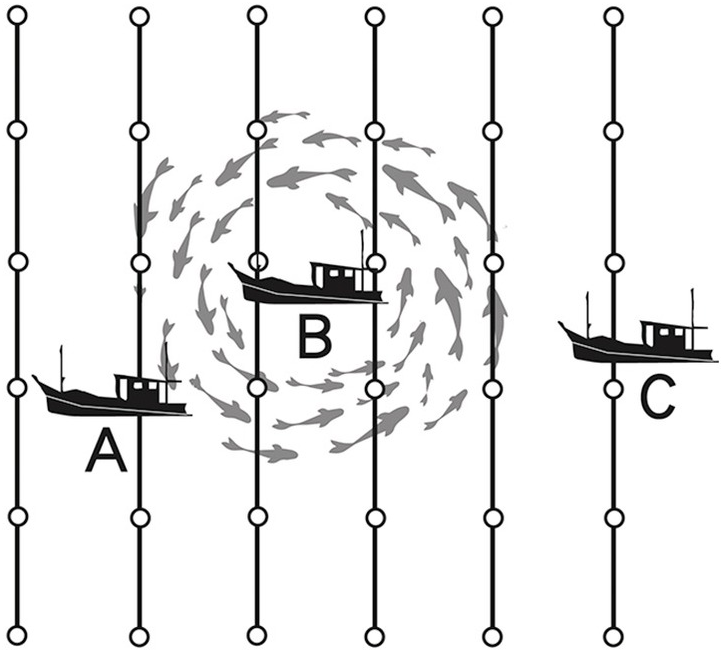

Beginning with the establishment of the WZA, the proportion of the population involved in the fishing economy steadily declined (J. Wang Reference Wang2000: 165–6), with many fishing villages emptied out by emigration to Taiwan. Most of the Matsu people who moved to Taiwan came from fishing villages such as Beigan’s Qinbi and Qiaozi, Nangan’s Ox Horn and Jinsha, and Juguang’s Fuzheng and Tian’ao (S. Cao Reference Cao1978). Indeed, the implementation of military rule had a tremendous effect on the fishing economy, such that fishermen could no longer make a living. After Matsu was militarized, the unrestricted movement of fishermen on the seas was deemed a threat to national security; fishermen were seen as “internal enemies” and potential leakers of military secrets. The state started to implement a series of stringent rules and inspections to reduce any potential threat.1 The procedure was as follows: anyone wanting to work in the fishing economy was required to apply to the village administrative office. Each applicant needed to supply three guarantors and was required to pass a clearance check before he could receive a fishing license.2 A licensed fisherman had to register with the village administrative office the day before he wanted to go fishing and receive a day permit. Before he set out, the fisherman had to show his fishing license and permit to the port authorities and pass an inspection before the guards would return his oars (for sampans) or motor starter (for motorboats). Every fishing trip had to have at least three people, and the boat was required to return with the same personnel onboard (Z. Chen Reference Chen2013: 80). These layers of onerous restrictions served to control fishing on and off the water.

Military officials worried that once at sea, Matsu fishermen could come into contact with fishermen from enemy territory and leak military secrets, so they established fishing boundaries that could not be crossed. In addition to being assigned a serial number, fishing vessels were required to fly an official flag so as to be more easily monitored. If fishermen crossed over a boundary or were suspected of fishing outside the allowed zone, upon return they would be restricted from going out again for at least a week, face interrogation and sometimes torture, be subject to jail time, and could even be banned from the water for extended periods. When any boat returned to harbor, the port authorities would inspect it for contraband and again impound the oars or motor.

Given the enormous maritime area, however, there were necessarily sporadic gaps in military control and surveillance. Matsu fishermen had a keen sense of where they could go at sea to avoid the eyes of soldiers, and where they could have contact with fishermen from the other side of the Strait: “Sometimes, when the weather was good, we’d run into them and hide someplace we couldn’t be seen to chat. But when we came back, we wouldn’t dare talk about it…otherwise we’d be locked up!”3

Matsu and mainland fishermen behaved like old friends when together, conversing congenially, joking and laughing with each other. They shared a mutual understanding, and did not participate in the enmity between the KMT and the CCP: