In the mid-1970s, the Frankfurt branch of the Turkish bank Türkiye İş Bankası distributed a roadmap to Turkish guest workers.Footnote 1 Hoping to wrest this hotly desired customer base from the clutches of leading West German competitors such as Deutsche Bank and Sparkasse, Türkiye İş Bankası – like many Turkish firms of the time – appealed to the guest workers’ nostalgia for home. The front cover depicts a quaint Bavarian scene, with a cheerful blonde man in full Lederhosen and a traditional feathered cap, grinning as he drinks from a foamy beer stein. In stark contrast, the back cover features a modernizing, industrial Turkey, with a skyscraper looming behind a Turkish half-moon flag. The message is clear: in the years since the migrants had left the poverty and dilapidation of their home villages in the hopes of amassing great wealth, Turkey, too, had begun to industrialize. Investing their Deutschmarks in Turkish banks would not only be as lucrative as investing in West German ones but would also support the economy of their homeland – and, accordingly, the well-being of the families they left behind.Footnote 2

More striking than the roadmap’s advertising strategy are its contents once unfolded.Footnote 3 The map does not depict the municipal street plan of Frankfurt, where the would-be customers lived, but rather a much broader system of international highways, centered around Europastraße 5 (E-5), or Europe Street 5, which stretched from West Germany by way of Munich through Austria, Yugoslavia, and Bulgaria to Istanbul.Footnote 4 At the height of the Cold War, the road featured on the map traversed the entire Central European continent, providing a clear-cut path across the imagined boundary of the Iron Curtain. Given that guest workers had been recruited to work and live within the spatial confines of West Germany, the map’s expansive reach is puzzling. If guest workers lived right in the bank’s own backyard, why would they need a map of Cold War European highways? Would it not have been more pertinent to provide a map of Frankfurt’s own roadways, which the guest workers could have used to find their way from their homes to the bank branch?

The map of Cold War Europe’s international highways was in fact a crucial tool for Turkish guest workers in West Germany. At least once per year, they revved the engines of their (usually) pre-owned Mercedes-Benzes and Fords – for many, the products of the factories at which they worked – and set off on a three-day car ride on Europastraße 5 en route to Turkey. Perhaps best conceived as small seasonal remigrations, or even pilgrimages, vacations to the home country were widespread activities, occurring during the summer months and less commonly during Christmas time. While the West German government and media tended to use the German word Heimaturlaube, or “vacations to the homeland,” the guest workers themselves, as well as those in the home country, typically used the Turkish word izin, which translates literally to “permission” or “leave.” As Ruth Mandel has noted, the concept of “leaving” or “taking leave” was in reality more of an “undertaking,” since the car ride involved not only substantial planning and capital expense but also long travel times, dangerous roads, emotional energy, and physical exhaustion.Footnote 5

While financial expenditure sometimes prohibited guest workers from taking the trip every year, they generally made it a priority. Far more so than letters, postcards, phone calls, and cassette recordings, physically traveling to Turkey assuaged homesickness and fears of abandonment because it allowed guest workers and their families to reunite face-to-face. In the 1960s, when single guest workers yearned for their spouses, children, parents, and lovers left behind, vacations gave them the sole opportunity to hug, kiss, and spend time together. With the rise in family migration of the 1970s, vacations assumed new meaning as a crucial tactic for preserving “Germanized” children’s connection to Turkey. For children who grew up primarily in Turkey, vacations were generally joyous occasions to spend time with dearly missed friends. For children born or raised in West Germany, vacations familiarized them with a faraway “homeland” that they might otherwise have known only from their parents’ stories.

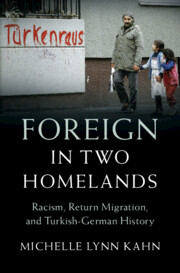

But the seemingly mundane act of taking vacations, as this chapter reveals, held much more significance: the road trip across the Iron Curtain, as well as the reunions upon arrival, not only tied the migrants closer to their friends, family, and neighbors at home, but also pushed them farther apart. The migrants’ unsavory experiences traveling through socialist Yugoslavia and communist Bulgaria on the E-5 confirmed their affiliation with the democratic, capitalist “West,” encouraging them to transmute their disdain for the Cold War “East” onto the perceived underdevelopment of Turkish villages. And more so than the rumors of abandonment, face-to-face contact provided firsthand impressions of how, year after year, guest workers and their children increasingly transformed into Almancı, or Germanized Turks. This sense of cultural estrangement involved not only mannerisms and language skills but also material objects. Even though in reality most struggled financially, guest workers used their vacations as an opportunity to perform their wealth and status as evidence of their success – that they had “made it” in Germany. Envious of the cars and consumer goods that guest workers flaunted upon their return, those in the homeland began to perceive the migrants as a nouveau-riche class of superfluous spenders who were out of touch with Turkish values and had adopted the habit of conspicuous consumption – a trait that many Turks associated with West Germany at the time (Figure 2.1). By using their Deutschmarks selfishly rather than for the good of impoverished village communities, they had stabbed their own nation in the back.

Figure 2.1 A quintessential portrayal of an Almancı, whom Turks in the home country denigrated as superfluous spenders, flaunting his Deutschmarks and posing proudly in front of his loaded-up car, 1984.

Travelers, Tourists, Border Crossers

Despite spending long hours performing what West Germans called “dirty work” (Drecksarbeit) in factories and mines, Turkish guest workers were by no means an oppressed, nameless, faceless proletariat exploited by their employers and tied to their places of work as immobile peons. They experienced vibrant lives and social interactions centered not only in the space of the company-sponsored dormitory but also throughout West German cityscapes – participating to varying degrees in the world around them through everyday activities such as eating at restaurants, drinking at bars, attending cultural events, and shopping.Footnote 6 Yet guest workers and their family members in Germany did not spend their leisure time only in the cities surrounding their workplaces. Nor did their excursions take place only after work hours and on weekends. Rather, the migrants were highly mobile border crossers, who took vacations to other European countries during their holiday breaks from work and, at least once per year, traveled back to Turkey to visit their families, neighbors, and friends. The ability to take lengthy vacations of up to four weeks at a time, given West Germans’ generous paid leave policy, was not only central to their personal migration experiences but also created much broader tensions. Employers imposed harsh disciplinary measures, including firing, on guest workers who failed to return to work on time, and the West German and Turkish governments – along with corporations – jockeyed to control and profit from guest workers’ travel.

Effective trade unions, a powerful component of political life in the West German social welfare state since the establishment of the Federal Republic in 1949, ensured that guest workers received time off from their jobs – particularly during Christmas and summertime, when their children were out of school. Although guest workers’ relationships with the trade unions were strained by discrimination and mistrust, trade unions upheld West Germany’s “right to vacation” (Urlaubsrecht), which was codified in 1963, just two years after the signing of the guest worker recruitment agreement with Turkey.Footnote 7 The Federal Vacation Law (Bundesurlaubsgesetz), which applied also to guest workers, required employers to provide a minimum of twenty-four days, or roughly five weeks, of paid vacation per year.Footnote 8 Accompanying the legally codified right to vacations was another perk: guest workers’ work and residence permits, which afforded them the opportunity to travel freely throughout other European Economic Community member states – a privilege extended to other Turkish citizens only when in possession of tourist visas.

While the most common form of travel was the Heimaturlaub or izin vacation to Turkey, many others went sightseeing in nearby Western European countries. Family photographs depict groups of primarily male guest workers tanning on beaches in Cannes and posing in front of the Seine River in Paris, the narrow alleys of Venice, and the many fountains of Amsterdam – all the while smiling with cameras hanging around their necks.Footnote 9 Those who lived in West Berlin regularly took day trips (Tagesausflüge) to East Germany, since unlike West Germans, Turkish guest workers were permitted to cross the Berlin Wall with foreign tourist visas, as long as they returned by midnight.Footnote 10 Taking these trips, especially those to Western Europe, was a matter of privilege, however. Despite affordable bus and train travel to neighboring countries, even a short weekend trip still entailed great financial expense. Guest workers therefore needed to calculate whether they had sufficient funds left over for a short getaway after paying for rent, food, and other basic necessities and sending remittances to their families in Turkey.

Guest workers generally recalled their vacations to Western Europe fondly. Yaşar, the self-appointed “social organizer” of a local music club in Göppingen, enjoyed planning semiannual affordable bus tours of neighboring countries for around fifty of his German and Turkish friends and their family members.Footnote 11 He and his wife also took frequent weekend trips to nearby Switzerland, where they stocked up on the famed Swiss chocolate to bring back to Turkey as gifts. London, with its bright red double-decker buses, proved especially exciting. But France was his favorite country, because a friendly Parisian woman had once offered him assistance when he was lost. While his trips to Italy were “not as nice,” he delighted in the scenic beauty of Venice. Though based on limited experiences and anecdotal encounters, Yaşar’s pleasant experiences during these travels shaped his identity. While he felt adamantly Turkish, he insisted that he “lived like a European” – despite having to decline pork while trying national cuisines.

Gül, whom neighbors in Şarköy called “the woman with the German house,” fondly recounted visiting Istanbul for her sister’s engagement party in 1965 – a trip that surprisingly led to a marvelous vacation in Vienna. Always eager to chat, the then twenty-nine-year-old seamstress struck up a conversation with a middle-aged Austrian couple who were traveling on the same train as tourists to Istanbul. The couple invited Gül and her sister to visit them at their posh home in Vienna. After a week of drinking Viennese coffee and sightseeing, most memorably at the stunning Schönbrunn Palace, the sisters took a train to Gül’s home near her textile factory in Göppingen. The journey allowed Gül not only to experience life in Vienna but also to help her sister enter West Germany as a tourist and work “quietly” (in Ruhe) – a euphemistic term that Gül used to describe her sister’s illegal employment.Footnote 12 Like Yaşar, Gül developed a positive impression of Western Europe, associating it with friendliness, beauty, consumption, and luxury even decades later.

Despite the prevalence of touristic travel throughout Western Europe, most guest workers took their annual leave all at once and used it during the summer for a one-month stay with their relatives at home. This pattern resulted in a massive summertime increase in travel between the two countries. Despite Turkey’s status as a NATO member state, it was still relatively low on Germans’ list of vacation destinations during the 1960s, not least because of the distance, the language barrier, and longstanding tropes about Muslim cultural difference. When Germans did travel to Turkey, they typically expressed a sort of Orientalist curiosity about the exotic “East.” As one 1962 travel guide described it, “the land between Europe and the Orient” was so tantalizing that German visitors “never packed enough film for their cameras” and “one always hears the joyful cries: ‘Oh, these colors, this vibrancy, this diversity!’”Footnote 13 Travel from Turkey to West Germany was also relatively limited. In 1963, the Turkish newspaper Cumhuriyet advertised a company called Bosphorus Tourism that offered bus tours from Istanbul to Rome, Paris, London, and Hamburg, with stops along the international highway Europastraße 5 in Sofia, Belgrade, Vienna, and Munich.Footnote 14 But affording these lavish tours, especially given the high currency exchange rate, was a privilege available only to elite, wealthy, urbanites.

Yet the existing tourism offerings were no match for the guest-worker-fueled boom in travel between the two countries in the 1960s. To accommodate vacationing guest workers, the West German government, railway system, and individual firms all organized special travel options. In 1963, the Ford factory in Cologne granted Turkish guest workers an additional three weeks of vacation time and contracted special trains for them, with discounted roundtrip tickets.Footnote 15 During the 1972 Christmas season, the German Federal Railways (Deutsche Bundesbahn) commissioned special half-priced charter trains to the home countries of all guest worker nationalities.Footnote 16 Political events also put officials on alert for a surge in guest worker travel. In anticipation of the June 5, 1977, parliamentary elections in Turkey, for which voting by mail was not an option, the Federal Railways once again organized charter trains from Frankfurt and Munich to Istanbul.Footnote 17

Guest workers’ vacations were also a matter of international importance, creating conflict between the West German and Turkish governments when it came to air travel. Though flying was far less common than driving in the 1960s and 1970s, airlines competed over guest workers as customers. In April 1970, representatives from both countries’ governments and airlines signed a “pool agreement” between Turkey’s publicly owned Turkish Airlines and the West German private companies Lufthansa, Atlantis, Condor, Bavaria, GermanAir, and PanInternational.Footnote 18 Aiming to even the playing field, the pool agreement fixed prices between Istanbul and ten German cities and required guest workers’ air travel to be split 50–50 between the two countries. West German firms, however, complained that Turkish Airlines (and hence the Turkish government) was breaching the agreement. Turkish Airlines’ monopoly in Turkey due to the ban on private companies serving Turkish airports meant that it could offer a much more flexible schedule, whereas competition among West Germany’s private airlines required dividing the number of flights among them. West German flights were permitted to land only in Istanbul, whereas Turkish Airlines could serve all the country’s airports. Rumor also had it that Turkish Airlines tickets were available on the black market for cheap and that passing through customs in Turkey was much easier if a guest worker traveled on Turkish Airlines.Footnote 19

Amid the Cold War context of Germany’s internal division, tensions over guest workers’ travels also strained relations between East and West Germany. In the 1960s, guest workers living in West Berlin flew to Turkey without exception through West Berlin’s Tegel Airport. Problems began in 1973, however, when Turkish Airlines began offering flights through East Berlin’s Schönefeld Airport. Given the cheaper prices and Schönefeld’s closer proximity to the heavily Turkish neighborhoods of Kreuzberg and Neukölln, guest workers increasingly opted to cross the Berlin Wall and fly out of East Berlin. The situation intensified in 1977, when East Germany’s budget airline Interflug commenced flights to Turkey, attracting 45 percent of guest workers. Concerned about the detrimental economic effect, the West German government repeatedly implored the Turkish government to reduce the number of Turkish Airlines flights through Schönefeld and to pressure Interflug to adhere to the fixed prices.Footnote 20 Yet little changed. In 1981, in an expression of Cold War paranoia, the West German newspaper Die Zeit attributed the “unfair competition” to a Moscow-led conspiracy to destroy the West German economy.Footnote 21

In terms of everyday life, guest workers’ vacations often caused conflicts with employers. Despite the legal right to vacation, their work and residence permits were beholden to the whims of floor managers, foremen, and other higher-ups prone to discriminating against Turkish employees, and a tardy return made a convenient excuse for firing them. Rumors about these firings became especially worrisome after the 1973 OPEC oil crisis, the associated economic downturn, and the subsequent moratorium on guest worker recruitment, when criticisms of Turkish workers “taking the jobs of native Germans” increased. The metalworkers’ trade union IG Metall spoke out against an “immoral” trend whereby some employers handed out termination-of-contract notices before the holiday season and then promised the workers their jobs back if they returned early enough.Footnote 22 Such clever though nefarious policies forced guest workers to choose between losing their jobs or sacrificing the opportunity to travel home. Although these discriminatory policies were rare, the rumors influenced guest workers’ decisions. A representative of the German Confederation of Trade Unions noted a marked decline in the number of Turkish guest workers who booked trips home via the German Federal Railways, which she attributed to their fear of being fired even though these concerns were “mostly unfounded.”Footnote 23

Termination due to late return from vacation was most publicized during the August 1973 “wildcat strike” (wilder Streik) at the Ford automotive factory in Cologne, during which as many as 10,000 Turkish guest workers went on strike for multiple days alongside their German colleagues.Footnote 24 The Ford strike marked a turning point in Turkish-German migration history: taking place just months before the recruitment stop, it was a crucial moment of Turkish activism, resistance, and agency in which migrants demanded their rights and proved that they were not an easily disposable labor source.Footnote 25 In a transnational frame, the Ford workers were also inspired by the hundreds of organized strikes by trade unions in Turkey, which contributed to Turkey’s 1971 and 1980 military coups and stoked fears that guest workers would import Turkish leftist radicalism into West Germany amid the Cold War.Footnote 26 Despite protesting labor conditions broadly, the immediate trigger of the Ford strike was the firing of 300 Turks who returned late from their summer vacations.Footnote 27 Süleyman Baba Targün, one of the strike’s leaders, had missed the deadline to extend his work permit because of car trouble while driving along the Europastraße 5. Although Targün’s work permit had expired just days prior to his reentry into West Germany, the Foreigner Office (Ausländeramt) of Cologne classified him as “illegal.” Partly as payback for his leadership role in the Ford strike, his appeal to the federal government to extend his residence permit was rejected. By Christmas, Targün was set for deportation to Turkey, where, to compound his problems, he faced a prison sentence for anti-government political activity.Footnote 28

Despite such high-profile cases, most guest workers took comfort in knowing that their right to vacation remained “just as firm” as it did for Germans – as long as they returned punctually.Footnote 29 Still, when threatened with travel delays, they often went to great lengths to avoid being fired. In 1963, one guest worker asked a Turkish Railways station director to send his boss a telegram testifying that his tardy return owed to a heavy snowfall that had prevented trains from traveling between Edirne and Istanbul.Footnote 30 In 1975, in a far more tumultuous and widely publicized situation, a Turkish Airlines flight from Yeşilköy to Düsseldorf carrying 345 Turkish passengers returning from their summer vacations made headlines when a twenty-four-hour delay caused massive unrest. Infuriated passengers ran onto the runway and attempted to storm the aircraft, shouting “Why are you treating us like slaves?” and “Rights that are not given must be taken!” To suppress the insurrection, airport security officials blocked the protestors with tanks. Several passengers were injured, and a father traveling with his young son was rushed to the hospital after fainting due to poor ventilation in the terminal.Footnote 31 To avoid such situations, guest workers adjusted their travel plans accordingly. Following this incident, Yılmaz avoided Turkish Airlines and opted for the reputed “German punctuality” of Lufthansa.Footnote 32

Guest workers’ job security was also jeopardized by shady Turkish travel agents, who exploited them by forging tickets and selling far more seats than were available. One guest worker collaborated with GermanAir as co-plaintiffs in a lawsuit against a travel agency that had overbooked a flight from Istanbul to Düsseldorf, resulting in his tardy return.Footnote 33 The problem was more systemic, however. In 1970, officials at the Düsseldorf Airport complained to the West German transportation ministry about a nightmarish day, with one problem after the other – all caused by Turkish travel agencies.Footnote 34 Anticipating an influx of Turkish travelers, the airport had not only commissioned additional border officials for passport checks, but had also set up a 4,000 square-foot tent outdoors, with makeshift check-in counters, luggage carts, chairs, lighting, loudspeakers, toilets, and even a refreshment stand. But even more travelers arrived than had been expected, and by noon it became clear that hundreds held fraudulent tickets. In one of many such incidents, 110 passengers were stranded for three days because their travel agency had sold enough tickets for two flights even though only one had been scheduled. Expressing no sympathy, some blamed the “chaos” not on the travel agencies, but on the travelers. The next day, Neue Rhein Zeitung reported that “hordes” of “men of the Bosphorus” from the “land under the half-moon” had been “shoving themselves” through the airport and having “temper tantrums.” “But what’s the point?” the article quipped: “After all, for 450 DM to Istanbul and back, you can’t expect first class service.”Footnote 35

As this racist and Orientalist rhetoric suggests, many West Germans exploited guest workers’ right to vacation as another weapon in their arsenal of discrimination. Not only did employers use a tardy return as an excuse to fire unwanted workers, but the overwhelmingly negative portrayal of guest workers’ travel reinforced stereotypes of Turkish criminality and backwardness that cast Turks as shady, deceitful, and dangerous. German airline firms blamed both Turkish Airlines and the Turkish government for violating international agreements. Airport officials lambasted Turkish travel agencies’ shady business practices and emphasized the overall chaos of being overrun by Turkish passengers. And, even though the guest workers were the real victims in these situations, the German media portrayed them as temperamental, violent aggressors who threatened the stability of air travel. Guest workers’ vacations were thus not only a private but also a public matter: their mobility could also be mobilized against them.

On the “Road of Death” through the Balkans

Far more than trains, buses, and airplanes, most guest workers vacationed to Turkey by car. Cars not only permitted autonomy and flexibility, but also served as a means of transporting large quantities of consumer goods from West Germany to Turkey and of securing heightened social status among friends and relatives. In the 1960s and 1970s, the only major route from West Germany to Turkey was the Europastraße 5 (Europe Street 5, or the E-5), the 3,000-kilometer international highway that spanned eastward across Central Europe and the Balkans through neutral Austria, socialist Yugoslavia, and communist Bulgaria, passing through Munich, Salzburg, Graz, Zagreb, Belgrade, Sofia, and Edirne. An alternative sub-route, which bypassed Bulgaria and went through Greece and the Yugoslav–Greek border at Evzonoi, posed too lengthy a detour. And while some Turks in West Berlin opted for a different route through East Germany, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria, the E-5 was by far the most common.

The journey across Cold War Europe was not easy. Traumatizing for some, adventurous for others, the drive from Munich to Istanbul alone lasted a minimum of two days and two nights, assuming the driver sped through, and much longer if they stopped along the way to catch much-needed shut-eye at a local roadside hotel. Yet, even as the migrants sighed with relief and kissed the ground as they crossed the Bulgarian-Turkish border at Kapıkule, the journey was not over. Considering that most Turkish travelers were journeying to Anatolian hometowns and villages much farther than Istanbul, such as the eastern provinces of Kars and Erzurum, the journey could take three or four days. Aside from the tediousness, the car ride also posed numerous dangers because of poor infrastructure, as well as traffic and weather conditions. Unpaved roads, seemingly endless lines of vehicles steered by overtired drivers, bribe-hungry border guards, fears of theft and vandalism, sleeping in cars, eating and urinating along the road – all remain vividly etched in both personal memory and popular culture. Reminiscing about both the hardship and the emotional significance of the journey, one Turkish migrant wrote in a poem: “Between Cologne and Ankara / One must speed through to arrive. / In between lie three thousand kilometers. / Who would drive it if he were not homesick?”Footnote 36

Turks were not the only guest workers who made the arduous annual trek along the E-5. The geography of the European continent meant that Yugoslavs and Greeks took the same route. Given that Yugoslavia was geographically closer to West Germany, Yugoslavs’ journey was a day shorter. Greeks, rather than passing through Bulgaria like Turks did, veered rightward at the Yugoslav city of Niš, switching to a different route through Skopje, Evzonoi, and Thessaloniki all the way south to Athens. Because of the diverse nationalities of the travelers, West Germans and Austrians often homogenized the E-5 into a migration route not only for Turks but also for all guest workers and “foreigners.” Across nationalities, travelers often recalled similar experiences, albeit mediated by their own individual circumstances and the varying historical, social, and cultural ties they had to the countries that they passed through. Nevertheless, given that Turks became West Germany’s largest ethnic minority in the late 1970s – and hence numerically the largest group of vacationing migrants – the E-5 gradually became associated primarily with them. While each migrant had a distinct narrative of their journey, their accounts converged into a collective experience that fundamentally shaped their identities and broader Cold War tensions.

The E-5 earned numerous monikers and substantially shaped the way that all Turks, not just guest workers, imagined migration. Guest workers typically referred to it fondly as “the road home” (sıla yolu), emphasizing its importance to their national identities. West German names ranged from “the guest worker street” (Gastarbeiterstraße), which emphasized that not only Turks but also guest workers from Greece and Yugoslavia traveled along it, to “the road of death” (Todesstrecke), which sensationalized its dangerous conditions and the high prevalence of fatal accidents. The highway was also ubiquitous in Turkish popular culture. E-5 is the title of Turkish author Güney Dal’s 1979 novel in which a man transports his deceased father along the highway for burial in his home country; this theme also appears in Turkish-German director Yasemin Şamdereli’s acclaimed 2011 film Almanya – Willkommen in Deutschland (Almanya – Welcome to Germany).Footnote 37 In 1992, Tünç Okan’s internationally released film Sarı Mercedes (Mercedes Mon Amour), based on Adalet Ağaoğlu’s 1976 novel, told the story of a guest worker’s journey along the E-5 to marry a woman in Turkey and show off his luxurious car.Footnote 38 The sixty-minute documentary E5 – Die Gastarbeiterstraße, directed by Turkish filmmaker Tuncel Kurtiz, was broadcast on Swedish television in 1978, and in 1988, the Turkish television series Korkmazlar aired an episode titled “Tatil” (The Vacation) in which guest workers travel along the E-5 to visit relatives in Turkey, giving rise to comedic cultural conflict along the way.Footnote 39 The road also appeared in music. “E-5” was the name of a Turkish-German music group formed in the 1980s, whose style – a mixture of rock n’ roll, jazz, and Turkish folk music – paid homage to the road connecting the “Occident” and the “Orient.” In 1997, the Turkish-German rap group Karakan recalled their childhood road trips in a song titled “Kapıkule’ye Kadar” (To Kapıkule) named after the Turkish-Bulgarian border.Footnote 40

The most extensive media portrayal of the E-5 was an alarmist, ten-page article in the leading West German newsmagazine Der Spiegel, published in 1975 (Figure 2.2). The article sensationalized the treacherous conditions along the E-5 – which, it elaborated, ensured “near-murder” and “certain suicide” – and noted forebodingly that annual fatalities on E-5-registered roads exceeded those on the entire Autobahn network, as well as the number of casualties in the previous decade’s Cyprus War.Footnote 41 A 330-kilometer stretch through the curvy roads of the Austrian Alps – precarious during the summer but even worse during the icy winter – was allegedly the site of over 5,000 accidents annually, and on the highway’s Yugoslav portion, one person supposedly died every two hours. As the article explained, travelers who did not succumb fatally to this “rally of no return” faced psychological torment due to tedious stop-and-go traffic, with bottlenecks caused by accidents in poorly lit tunnels. Particularly notorious were two unventilated 2,400- and 1,600-meter tunnels in Austria, which plagued travelers with anxiety and shortness of breath.Footnote 42

Figure 2.2 Map of the Europastraße 5 (E-5), titled “Death Trek to Istanbul,” published in a sensationalist 1975 article.

Reflecting anti-guest worker biases prevalent in Der Spiegel at the time, the same article blamed these harsh conditions not only on environmental and infrastructural problems but also on the guest workers themselves. Invoking rhetoric common in criticism of migrants, the article described the caravan of cars filled with Turkish travelers as an “irresistible and uncontrollable force” and a “mass invasion,” which posed serious problems for local Austrian communities and border officials. In 1969, local officials near Graz had called upon the Austrian military for assistance in policing guest workers’ traffic violations, resulting in the deployment of six tanks and 120 steel-helmeted riflemen – an incident that the newspaper jokingly called “the first military campaign against guest workers.” As the years passed, officials increasingly felt their hands tied. One Senior Lieutenant of the Styrian state police expressed frustration at the number of cars needing standard ten-minute inspections at the Austrian-Yugoslav border: “If we were to catch eight Turks in a five-person car, what would we do with the surplus? Should we leave behind the grandma and the brothers, or the children? Who would take them in? The nearest hotel, the community? Or should we establish a camp for [them]? Here I am already hearing the word ‘concentration camp!’”Footnote 43 While it is unclear who was beginning to invoke the term “concentration camp,” the lieutenant’s remark demonstrated his self-conscious concern that, in the aftermath of the Holocaust, the detention of foreign travelers – particularly elderly women and children – could devolve into public accusations of human rights violations.

Centuries-old tensions between the Ottoman and Habsburg Empires were also a reference point. Dramatically, the article quipped: “‘The Turks are coming!’ has become a cry of distress for Alp-dwellers and Serbs – almost as once for their forefathers when the Janissaries approached on the very same age-old path.” By condemning Turkish travelers as a terrifying invasion of Janissaries, the elite corps of the Ottoman Empire’s standing army, Der Spiegel alluded to the bloody 1683 Battle of Vienna, which occurred after the Ottoman military had occupied the Habsburg capital for two months. And by explicitly using the phrase “ancient migration route,” the article characterized the region not as strictly demarcated by national borders, but rather as a space of deeply rooted travel, mobility, and exchange. However facetious, the interpretation reflected the importance of the Ottoman past in shaping twentieth-century attitudes toward Turkish guest workers. Nearly three hundred years later, ancient hatreds of “bloodthirsty Turks” and the Ottoman “other” remained a racializing anti-Turkish trope.Footnote 44

Far from a military threat, the article continued, local Austrians’ terror manifested in a constant onslaught of revving motors, piles of garbage, and human excrement. Making matters worse, the locals received little to no economic benefit from what might otherwise have constituted a touristic boon. To save money, Turkish travelers generally did not patronize Austrian restaurants, hotels, and souvenir shops. Instead, they preferred to sleep in their cars, eat pre-prepared meals, and cook using an electric stovetop. They also avoided Austrian gas stations because they considered refueling in Yugoslavia much more economical.Footnote 45 Despite these tensions, some local Austrians were willing to assist the travelers by placing cautionary Turkish-language signs on dangerous stretches of road and building a “Muslim Rest Stop” with a makeshift prayer room, meals free of pork and alcohol, and an Austrian transportation official on site.Footnote 46

The West German government, too, expressed concern about the E-5’s treacherous conditions. Around the same time as the sensationalist Der Spiegel article, the Federal Labor Ministry launched a public campaign to educate guest workers about proper driving habits. The forum was Arbeitsplatz Deutschland (Workplace Germany), a newsletter for guest workers published in multiple languages that sought to provide advice – sometimes useful, sometimes not – on aspects of life in West Germany. Many of the newsletter’s articles took a didactic, paternalistic tone. Presuming that many guest workers, especially the Turks, came from rural areas stereotyped as “backward,” the articles portrayed them as in need of enlightenment – or at least of a rudimentary orientation to the norms of life in “industrialized,” “urbanized,” and “modern” societies. In a series titled “The ABCs of the Car Driver,” which ran from the mid-1970s through the mid-1990s, the Labor Ministry instructed guest workers on traffic rules and safety, such as not driving without a license, following traffic signs and signals, paying more attention to children crossing the street, and eating a full breakfast to avoid hunger on the road.Footnote 47

Responding to the shocking media reports on the E-5, the newsletter published a six-page, multi-article feature sponsored by the German Council on Traffic Safety, titled “Vacation Safely in Summer 1977.”Footnote 48 The Turkish edition’s cover featured a dark-haired husband, wife, and three children loading suitcases into a car, about to embark on the journey to the “hot countries in the South.” Among the articles was a cautionary tale, in which a stereotypically named guest worker (“Mustafa” in the Turkish edition, “José Pérez” in the Spanish) had saved 4,000 DM to purchase a used van from his friend, only to find out halfway through his 3,000-kilometer journey that the brakes were defective. “Had Mustafa inspected the car beforehand? Far from it!” the article decried. “His friend had given him a ‘guarantee,’ saying the car was like new!” Mustafa had also failed to check alternative routes, insisting that his was the shortest, and refused to obey speed limits and to avoid forbidden entry roads. Guest workers like Mustafa, the newsletter insisted, justified their flagrant disregard for traffic safety with pride: “If you’re not brave, then don’t get on the road!”Footnote 49 While readership statistics are unavailable, the newsletter’s continued references to inept drivers on the E-5 in the 1980s suggest that the warnings had little impact.

Amid broader Cold War geopolitics, government and media reports also perpetuated self-aggrandizing critiques of socialism and communism by blaming the Balkan countries for the E-5’s dangerous conditions. While these reports typically attributed the dangers in Austria to snow, ice, and other inclement weather, Arbeitsplatz Deutschland echoed tropes of “Eastern” backwardness. Yugoslav roadways, the newsletter noted, were “not up to the standards of modern traffic.” In contrast to Germany’s esteemed Autobahn, only one-third of the E-5’s Yugoslav portion was paved, and traffic officers failed to enforce safety regulations. Travelers were thus forced to endure “curves and obstacles without warning, swerving trucks, cars without lights, tractors that disregard the right of way, and agricultural vehicles or even animals crossing the road.” Accompanying photographs depicted a large herd of sheep alongside a smashed car.Footnote 50

Guest workers, too, perceived an immediate change as soon as they crossed the Austrian-Yugoslav border into the Balkans. On the one hand, they took comfort in knowing that every kilometer they drove eastward brought them closer to their homeland. Some even felt a “comfortable ease and relaxation” in Yugoslavia and Bulgaria.Footnote 51 Murad recalled that one of the highlights of the trip was eating at a roadside restaurant in Yugoslavia that served ćevapi, a minced-meat kebab similar to the Turkish köfte, which reminded him of home.Footnote 52 Others recalled that Bulgarians were able to communicate using Turkish words, many of which had long entered the Bulgarian language.Footnote 53 This sense of shared culture, like Der Spiegel’s remark about Janissaries, further reflects the legacy of centuries-long Ottoman rule in the region.

Yet, overwhelmingly, Turkish travelers perceived extreme animosity from local Yugoslavs and Bulgarians, making the drive east of the Iron Curtain especially fearsome. This animosity, as Der Spiegel’s comment about Janissaries evidenced, owed in part to the especially bitter memory of Ottoman conquest in the Balkans.Footnote 54 Whereas Austrians’ fears of Ottoman invasion reached a height at the 1683 Battle of Vienna, Balkan populations endured both indirect and direct Ottoman rule that lasted in some areas from the fourteenth through the early twentieth centuries. Although Western European disdain for Turks subsided somewhat during Ottoman “westernization” campaigns of the Tanzimat Era (1839–1876), resistance to the oppressive “Ottoman yoke” spurred the Balkan nationalist movements and bloodshed of the nineteenth century.Footnote 55 In Bulgaria in particular, tensions persisted long after the downfall of Ottoman rule, and guest workers traveling on the E-5 in the 1980s did so in a climate in which Bulgaria’s communist government was engaged in a campaign of forced assimilation, expulsion, and ethnic cleansing against the country’s Muslim Turkish ethnic minority population.Footnote 56

These animosities assumed another layer during the Cold War. Socialism and communism in the Balkans contrasted with Turkey’s democracy and NATO membership, and the reality that guest workers were traveling from West Germany tied them further to the “West.” While they neither looked stereotypically German nor conversed primarily in the German language, the association reflected Cold War economic inequalities. The cars they drove were highly reputed Western brands (commonly BMW, Mercedes-Benz, Volkswagen, Audi, Opel, and Ford), and, when they exchanged money with local populations, they were identified not only by the materiality of their West German bills and coins, but also by their purchasing power. By contrast, access to Western consumer goods was rarer in Yugoslavia and Bulgaria. Although some Yugoslavs were able to acquire such products – either through international trade, shopping trips to neighboring Italy, or gifts from vacationing Yugoslav guest workers – scarcities and their less valuable currency imbued Western products with a cachet of luxury.Footnote 57 Such products were even harder to obtain in Bulgaria, even though, as Theodora Dragostinova has shown, Bulgaria was a crucial actor on the global cultural scene.Footnote 58

Although both Yugoslavia and Bulgaria were far more entangled with the “West” than Cold War rhetoric has historically maintained, Turkish travelers envisioned the Balkans in terms of “Eastern” backwardness and underdevelopment. These lasting prejudices solidified due to their everyday encounters with local populations, which were marred by violence, bribery, and corruption. Yugoslavia, exclaimed the Turkish rap group Karakan in their song about the E-5, was “full of crooks.”Footnote 59 One guest worker, Cavit, complained that rowdy Yugoslav teenagers would scatter rocks along the highway to cause flat tires and then rob and vandalize the cars when the weary drivers pulled over for assistance.Footnote 60 Tensions also occurred with Yugoslav police officers and border guards, who had a sweet spot for bribes. When Zehrin’s husband made a dangerous turn into a gas station, the police arrested him, confiscated the family’s passports, demanded a fine of 520 DM, and refused to release him until he gave them his watch as a bribe.Footnote 61 Another traveler recalled “sadistic” border guards who, in search of contraband, forced her family to completely empty their car. Fortunately, she remembered poetically, “Sweets and cigarettes appeased the gods of the border, and my cheap red Walkman worked to make one-sided friendships.”Footnote 62 Avoiding conflict was easier for Erdoğan, whose mother had grown up in Sarajevo and could communicate with the border guards, but his family still stocked up on extra Marlboro cigarettes, Coca-Cola, and chocolate bars just in case.Footnote 63

For many travelers, driving through Bulgaria was even worse than Yugoslavia. One child admitted to not knowing much about politics, but he recalled vividly that his first impression of communism was the absence of color: everything was gray. The only color was on the building façades, which were adorned with ideological murals touting the benefits of communism by depicting happy young workers – a stark contrast to the depressing faces he saw on the streets.Footnote 64 An additional stressor for him were visa laws that permitted Turkish citizens a mere twelve hours to pass through the entire width of the country. If a policeman caught a car idling, he would not hesitate to tap on the driver’s window, grunting “komşu, komşu” (neighbor, neighbor), a Turkish word that had become part of the Bulgarian lexicon.Footnote 65 Bulgarian children, too, apparently had a taste for bribes and would tap on travelers’ windows demanding chocolate and cigarettes. When Cavit refused, the children cursed him: “I hope your mother and father die!”Footnote 66

The anxiety-provoking time in Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, which confirmed guest workers’ preconceived distinctions between Western and Eastern Europe, did not entirely disappear when they crossed into Turkey. Far from a peaceful relief, the Bulgarian-Turkish border at Kapıkule was just as chaotic as the others they had crossed (Figure 2.3). The Turkish novelist Güney Dal described the scene in his 1979 book E-5: “German marks, Turkish lira; papers that have to be filled out and signed … exhaust fumes, dirt, loud yelling, police officers’ whistling, chaos, motor noises … pushing and shoving.”Footnote 67 Just like their Yugoslav and Bulgarian counterparts, Turkish border guards enriched themselves through bribery and extortion, and guest workers reported having to wait in hours-long lines of cars just to cross the border.Footnote 68 Murad rejoiced that his family was able to skip the lines because his uncle was the wealthy mayor of a local community.Footnote 69

Figure 2.3 Border guards inspect guest workers’ cars at the Bulgarian-Turkish border at Kapıkule, mid-1970s. The woman’s trunk is stuffed full of consumer goods, including a bag from the West German department store Hertie.

Despite the massive corruption, the Turkish media romanticized the treatment that guest workers received from Turkish border guards, compared to officials in the Balkans. In 1978, the Turkish newspaper Cumhuriyet published an overly rosy portrayal of the Kapıkule border crossing. Guest workers are warmly welcomed by “cleanly dressed and smiling customs officials” and “friendly but cautious police officers,” who are “very courteous and take care of you.” The passport check and customs inspection proceed “quickly.” Upon crossing the border, guest workers encounter local villagers who “smile, say hello, and wave to one another.” The experience is so pleasant that the guest workers “are filled with pride”: “With an expansive joy in your heart, you say, ‘This is my home.’”Footnote 70 While this report certainly contradicted reality, its stark contrast to the long lines and corruption in Yugoslavia and Bulgaria supported a nationalist narrative that touted the supposed superiority of Turkish hospitality and efficiency.

The Cumhuriyet report was more accurate, however, in its portrayal of the “pride” and “expansive joy” after the physically and emotionally exhausting three-day journey. In the travelers’ recollections of the Kapıkule border crossing, complaints about corruption are overshadowed by happiness and relief. One child recalled the joyous cries of “Geldik!” (We’ve arrived!) as her family’s car crossed the border, which seemed “like a gate of paradise.”Footnote 71 Another woman explained: “When we drive over the border in Edirne, I feel very relieved. I don’t know why. Maybe because it’s my own country, or maybe it comes from the dirt or the water. It doesn’t matter which one. There is a saying: a bird locked in a golden cage is still in its homeland … No matter how bad it is.”Footnote 72 As a symbol of this feeling of relief and renewal, many guest workers kissed the ground, washed their cars, and enjoyed fresh watermelon.Footnote 73

Not all travelers, however, felt a sense of familiarity. For many children who had been born and raised in Germany, Turkey seemed just as strange as Yugoslavia and Bulgaria – at least the first time they encountered it – and they described it not as their “homeland” but rather as a “vacation country” (Urlaubsland). Though long regaled with their parents’ happy tales of Turkey, some children felt a sense of culture shock. “I thought everything was very ugly,” Fatma recalled, criticizing Turkey’s infrastructure as “wild” compared to Germany’s “standardized” and “orderly” urban planning. “The bridges were sometimes not high enough to drive under. The buildings were partially crumbling. As a child, I thought: ‘What is this place?’”Footnote 74 In Gülten Dayıoğlu’s 1986 book of short stories, a teenage boy expresses a similar sentiment: he derides his parents’ village as little more than “mud, dirt, and crumbling houses,” and he mocks the villagers for living “primitively” and being “stupid, backward, conservative, strange people.”Footnote 75 Even the guest worker generation, who had grown up in the villages, sometimes came to view their former neighbors with disdain. People who remained in the villages, they noted, were “dumb,” “ignorant,” “uneducated,” “uncultured,” “old-fashioned,” “rigid,” and even “crazy.”Footnote 76

This derision of Turkey’s shoddy infrastructure and villagers’ cultural “backwardness” reflects the power that the journey along the E-5 had in shaping the migrants’ identities. Their unsavory experiences driving through Yugoslavia and Bulgaria made them disdain life in the communist and socialist East and solidified their identification with the perceived freedom, democracy, modernity, and wealth of the West. By bribing Yugoslav and Bulgarian police officers and border guards with Marlboro cigarettes, Coca-Cola, and Deutschmarks, vacationing guest workers not only testified to the porosity of the Iron Curtain but also assumed small roles as purveyors of Western consumer goods in the Cold War’s underground economy. And some migrants, particularly children, transmuted their disdain for Yugoslavia and Bulgaria’s perceived economic underdevelopment onto their parents’ home villages, employing the same tropes of Turkish “backwardness” that West Germans used to condemn Turks as unable to integrate. The E-5 was not only paved with potholes, ice, and accidents, but also with paradoxes: while it transported the migrants to Turkey, it also solidified the West German part of their identity.

Fancy Cars and Suitcases Full of Deutschmarks

Like the journey itself, the happy reunions upon the guest workers’ arrival were also marked by new tensions of identity, national belonging, and cultural estrangement. Every year, as guest workers returned to their home villages, the friends and relatives they had left behind gradually detected that something about them had changed. These local-level perceptions of the migrants’ newfound difference soon crystallized into Turkish public discourse and became crucial to the development of discourses about the Almancı, or “Germanized Turks.” Visual depictions of the Almancı evolved with the changing demographics of migration. Whereas the depictions of the 1980s emphasized the forlorn faces of the second-generation children who had grown up abroad and could barely speak Turkish, those of the 1960s and early 1970s focused on the first generation, the guest workers themselves, usually portraying the average Almancı in similar fashion: as a mustachioed man in button-down shirt, vest, and work boots, donning a feathered fedora, and – more often than any other accessory – carrying a transistor radio.Footnote 77

The prevalence of the transistor radio in the images of the first-generation Almancı points to the important role that Western consumer goods played in delineating the shifting contours of Turkish and German identities in a globalizing world. First hitting American and Western European markets in 1954, transistor radios were among the most purchased electronic communication devices of the 1960s and 1970s and were widely popular among guest workers. In fact, up to 80 percent of guest workers chose transistor radios as their first purchase in West Germany. Promising access to Turkish-language broadcasts, transistor radios became the crucial means for staying apprised of news from home.Footnote 78 In Turkey, however, transistor radios came to symbolize not the migrants’ connection to their homeland but rather their estrangement from it. Here, vacations on the E-5 were critical, for they were the channel by which guest workers transported radios, along with cars and myriad other German-made consumer goods, to Turkey. The cars and consumer goods brought on the E-5 were a major factor influencing Turkish perceptions of guest workers’ Germanization: the Almancı, according to the stereotype, had transformed into nouveau-riche superfluous spenders who performed their wealth and status in the face of impoverished villagers.

The association of guest workers with Western consumer goods was rooted in broader economic trends. In the 1960s and 1970s, Turkish state planners’ import substitution industrialization policy, which aimed for industrialization with minimal outside influence, resulted in a largely closed economy in which foreign-made goods were rare.Footnote 79 Like Yugoslavs and Bulgarians, Turks often romanticized the variety and quality of Western European and American consumer goods compared to the allegedly inferior Turkish brands.Footnote 80 The divide was starker in villages, where the importance of local production and the absence of running water and electricity ensured that residents had virtually no exposure to emerging products like washing machines and refrigerators.Footnote 81 While villagers’ previous exposure to industrial products had come through internal seasonal labor migration to Turkish cities, vacationing guest workers brought a far more astounding array of products, and the label “Made in Germany” held more cachet than “Made in Istanbul.”Footnote 82

Since the start of the guest worker program in 1961, the Turkish government encouraged guest workers to import West German goods to Turkey as part of a larger policy of using remittances to stimulate the country’s economy.Footnote 83 Advertised lists of duty-free items reflected the variety of objects that guest workers brought back. In the 1960s, the category of “home furnishings” (ev eşyası) included pianos, dishwashers, radios, refrigerators, and washing machines, and “personal items” (zat eşyası) included fur coats, typewriters, handheld video recorders, cassette tapes, binoculars, gramophones, skis, tennis rackets, golf clubs, children’s toys, hunting rifles, and one liter of hard alcohol.Footnote 84 Reflecting the new sorts of goods popular in Germany, the 1982 list included handheld and stationary blenders, fruit juice pressers, grills, toasters, chicken fryers, coffee machines, yogurt-making machines, and electric massagers.Footnote 85 The number of duty-free items also diminished. Previously duty-free items, such as video cameras and washing machines, now cost up to 700 DM to import, and the minuscule half-Deutschmark tax on a single child’s sock or slipper reflected the government’s growing desperation for revenue amid economic crisis.

No consumer goods, however, were as significant as the cars that guest workers drove along the Europastraße 5. Amid Western Europe’s postwar industrialization, cars held great social meaning. As a 1960s travel guide for Germans traveling to Turkey put it, “The man of our days wants to be independent. For him, the car is not only a demonstration of his social position, but it is also the most comfortable form of transportation.”Footnote 86 Guest workers’ desire to purchase their own cars ran deeper, however. Psychologically, Der Spiegel insisted, cars were a “fetish” for all guest workers: “When Slavo in Sarajevo, Ali in Edirne, and Kostas in Corinth roll up with their own Ford, BMW, or even Mercedes, then the frustration of months on the assembly line in a foreign country turns into a pleasant experience of success in the homeland.”Footnote 87 Through their cars’ “modern” symbolism, the “scorned, mocked, and exploited pariahs of industrial society” could transcend their socioeconomic status, making their backbreaking labor worthwhile.

The cachet of guest workers’ cars was especially palpable in Turkey in the 1960s and 1970s, when car ownership was rare. The first Turkish sedan, the Devrim, was produced in 1961, the same year as the start of the guest worker program, and the first mass-produced Turkish car, the Anadol, did not begin production until 1966.Footnote 88 Whether purchasing an Anadol in Turkey or paying expensive taxes to import a car from abroad, the high cost of car ownership ensured that they were a luxury available only to wealthy urbanites. Even among the wealthy, however, the number of cars remained minuscule: for every 1,000 people in Turkey, there were only four cars in 1971 and, despite increasing, the number remained relatively low in 1977, at just ten per thousand.Footnote 89 The symbolic value of a car was especially pronounced in villages and smaller towns: while Turkish urbanites were familiar with cars by the late 1960s, most villagers had never seen a car with their own eyes until vacationing guest workers returned with them. In both cities and villages, Turks in the home country began to associate guest workers nearly synonymously with West German car brands: Mercedes-Benz, BMW, Volkswagen, Audi, and Opel. Incidentally, these were the same automotive firms where many guest workers were employed, and many took special pride in showing off a car that they had helped produce. Even if their cars were rickety, used beaters that had been sold multiple times and had broken brake lights, they became symbols of the guest workers’ upward mobility.

Family members, friends, and neighbors in Turkey reacted to guest workers’ cars with a mixture of awe, bewilderment, and envy. In the 1960s, twenty-year-old Necla even based her decision to marry her husband, Ünsal, on his car (Figure 2.4). Before their marriage, Necla knew nothing about Ünsal – only that he was from a small village five kilometers east of Şarköy, where she had grown up, and that he had become captivated with her when he caught a glimpse of her during his vacation from Germany. Although Necla’s father scrutinized potential suitors, he entertained Ünsal’s request for marriage simply because he was a guest worker. When Ünsal asked Necla’s father for her hand, her mother forced her to stay in her room, insisting that she should not see her suitor before the formal arrangement. Nervously awaiting Ünsal’s arrival, Necla peeked out the window and was delighted at what she saw. Although she could barely see Ünsal’s appearance from far away, one thing was certain: he had a car, a gray Mercedes-Benz. “That car had come to me like a fairy tale,” Necla gleefully recalled fifty years later. “All I knew was that he was a wealthy man and that he was working in Germany. I just had to marry him.”Footnote 90

Figure 2.4 Ünsal Ö., Necla’s husband, with his blue Opel – one of the eighteen cars that he bought and sold during his two decades living in West Germany before remigrating.

Guest workers also coveted cars as an additional income source. In 1963, Anadolu Gazetesi reported that 500 workers at the Ford factory in Cologne had purchased used cars to drive to Turkey to sell.Footnote 91 Selling West German cars in Turkey was so prevalent that the Turkish government instituted strict customs regulations to prevent competition with the emerging Turkish automotive market. In 1973, Turkish citizens who had worked in West Germany for at least two years could import one small- or medium-sized passenger vehicle – but only upon their permanent remigration. Within six months of their arrival, the returning workers had to register their cars to ensure they had a valid Turkish driver’s license. Although they could import a tractor for farming, they were restricted to a list of twenty-one “permitted tractor brands,” including Massey Ferguson, Ford, Caterpillar, and John Deere, and the duty-free import of trucks, vans, buses, and minibuses was “strictly forbidden.”Footnote 92 Circumventing these restrictions, guest workers regularly sold cars on the black market.Footnote 93 During their thirty years in Germany, Necla and Ünsal purchased eighteen used cars, most of which they sold for cash in Turkey.

Cars were not only modes of transportation, status symbols, and income generators, but also vessels for transporting other consumer goods. Personal vehicles’ capacity for mass quantities of luggage was a major factor motivating the decision to drive rather than fly to Turkey, compared to airlines’ harsh baggage restrictions. One guest worker had even offered a 100 DM bribe to a baggage handler at the Düsseldorf airport to load his massively overweight suitcase onto the plane. To his dismay, however, bribes were far less successful at German airports than they were at Yugoslav, Bulgarian, and Turkish border checkpoints: an airport official wrote a formal letter of complaint to his employer, which was forwarded to the state and federal government transportation ministries.Footnote 94 The importance of cars’ capacity for luggage is captured in vacationing guest workers’ family photographs, which depict lines and lines of cars on the Europastraße 5 filled to the brim, complete with carefully tied-down rooftop luggage racks.Footnote 95 Güney Dal’s 1979 novel E-5 even features a curious subplot involving a blue porcelain bathtub tied to the roof of a car.Footnote 96 After the rise in family migration in the 1970s, guest workers deliberately opted for cars that could hold not only large quantities of luggage but also large families. The Ford Transit, a sturdy and spacious minibus first produced in 1965, became such an iconic symbol of the guest worker program that the German city of Bremen erected a statue of it in 2017 (Figure 2.5).Footnote 97

Figure 2.5 Turkish vacationers at a rest stop on the E-5 in Austria, ca. 1970. Their car, an iconic Ford Transit, is loaded to the brim with consumer goods, including a rooftop luggage rack.

Well aware that vacationing guest workers were loading up their cars with consumer goods, West German firms sought to take advantage of the phenomenon. In the 1960s, supermarkets and textile stores in West German cities began hiring translators to accommodate the large number of Turkish customers.Footnote 98 Local stores also advertised in newspapers oriented toward guest workers. The Frankfurt-based retailer Radio City, the self-identified “oldest and best-known Turkish firm in Germany,” boasted that its inventory included well-regarded companies, such as Grundig, Telefunken, Philips, and Siemens, that employed guest workers.Footnote 99 In the most blatant example of ethno-marketing toward Turks, the home improvement and construction store OBI, located in Berlin’s heavily Turkish district of Neukölln, distributed a Turkish-language flyer advertising special deals on auto equipment necessary for the drive along the E-5, including hydraulic car jacks, water pumps, and rooftop luggage racks (Figure 2.6). The ad featured a Turkish woman wearing a headscarf, shouting: “Run, run! Don’t miss the deals at OBI!”Footnote 100

Figure 2.6 Turkish-language ethno-marketing flyer from the West German home improvement store OBI, advertising auto parts and rooftop luggage racks to vacationing guest workers, mid-1970s. The woman, wearing a headscarf, shouts: “Run, run, don’t miss the deals at OBI!.”

While the OBI advertisement certainly exaggerated the haste of running to catch deals, it did capture the importance that guest workers placed on shopping before their vacations. Given stereotypes about guest workers’ riches, friends and relatives in Turkey expected to receive not only hugs and kisses but also gifts and souvenirs. The sheer pressure of pleasing relatives – and of not being perceived as poor, unsuccessful, or stingy – turned shopping into an annual ritual, and guest workers put extensive planning, effort, and expense into purchasing gifts. Birgül explained that her mother would take several days off work before the vacation to complete the shopping. “Everyone wants something from Germany because they think that the things here are much nicer,” she explained. At department stores, Turkish women would shop for dresses, skirts, blouses, shoes, and bed linens, while men generally assumed responsibility for larger items, such as radios, vacuums, and appliances. To introduce her friends to the latest fashions, Birgül brought lipstick, mascara, and nail polish, as well as copies of the magazines Burda, Brigitte, and Petra. Polaroid cameras, too, were hot items. Birgül recalled excitedly that when her father photographed villagers in Çorum and the prints came out, “They thought it was a miracle!”Footnote 101

Guest workers who were interviewed for this book confirmed this broad and oddly specific range of items. “Oh, we brought everything!” exclaimed Necla, the same woman who had married her husband because of his car.Footnote 102 Necla’s list contained small items, such as beauty products and cosmetics, as well as furniture, such as chairs, cabinets, and a television, even though her village did not yet have a broadcasting connection. Above all, however, Necla coveted cookware. She brought plates, pots, and pans, including a multi-piece American set of pots and pans with a 100-year warranty that she was still using as of 2016. Burcu, who was a child while Necla and Ünsal were traveling back and forth between the two countries, remembered Necla’s beautiful silver knife set even thirty years later, reminiscing, “I always loved those knives.” Burcu would also get excited when “Necla Teyze” (Auntie Necla) would bring her special presents, such as balloons – since Necla worked at a balloon factory in Dortmund – and even her first Barbie doll.Footnote 103

“Suitcase children,” who lived with relatives in Turkey and traveled to West Germany to visit their parents, also transported goods between the two countries. Bengü’s grandparents packed her suitcase with Turkish culinary staples like chili paste, garlic, olive oil, and dried okra, which were hard to find in Germany before the rise in Turkish markets and export stores established by former guest workers.Footnote 104 The only downside, she laughed, was that her clothes frequently smelled like garlic. Murad spoke fondly of transporting products on the other leg of the journey – from Germany to Turkey – which elevated his social status. “Turkey was like a socialist country back then,” he joked, elaborating that Turkey’s relatively closed trade policies made foreign products rare.Footnote 105 While his uncles asked for cigarettes and alcohol from the German airport’s duty-free store, his classmates demanded sweets: “Bringing chocolates was like gold!” With its Italian origins, the chocolate hazelnut spread Nutella made Murad especially “popular,” while Bengü’s classmates delighted in Switzerland’s Nesquik chocolate powder.

The West German media was curiously fixated on the shopping and “show-and-tell” at these reunions, emphasizing how guest workers – often arrogantly – performed their wealth and status. While newspapers mentioned vacationing guest workers, they focused on individuals who had remigrated permanently because it was then, when a guest worker had all his German-made possessions centralized in his village, that he could fully flaunt his wealth. In 1976, Zeit-Magazin reported on Ahmet Üstünel, a thirty-year-old farmer who had returned to Gülünce after mining coal for five years in Oberhausen. He brought not only his wife and three children but also 30,000 DM (actually 28,509 DM and 33 pfennigs, per his meticulous calculations) saved through thrifty budgeting. Üstünel also owned not one, but two, vehicles: a brand-new McCormick 624 diesel tractor and the fully packed Volkswagen Variant. The shiny car, washed clean after the arduous three-day journey on the E-5 and boasting a West German license plate, attracted villagers’ awe and envy. As he drove past a local coffee shop, a group of children chased him down the street, hoping for treats. “Cigarette! Cigarette!” they yelled.Footnote 106

In a more comprehensive five-page article and photo series, titled “What Turks Do With Their Marks,” the West German magazine Quick profiled ten guest workers who had returned “from the golden West” and were now viewed enviously as “capitalists” and “little kings.”Footnote 107 Rather than praising the guest workers for achieving their dreams, the article belittled their frivolousness and naiveté in contrast to Germans’ allegedly wise and prudent financial decisions. Jusuf Demir, who had spent three years as a garbage truck driver in Langenfeld, smiled widely for a photograph to show off his shiny new gold teeth – “a good investment,” the article joked. The article further mocked Hursit Altınday, a former construction worker, for having built a “Swabian paradise on the Anatolian highlands,” complete with “German” features, like a bathroom, balcony, garden, and wrought-iron railing. The article also marveled at guest workers who leveraged their wealth to secure positions in local government, implicitly criticizing Turkish politics as nepotistic. One striking example was İbrahim Öksüz, who upon returning from Wuppertal with 100,000 DM, had been elected to the Şereflikoçhisar town council and was planning to run for a seat in the parliament. But “nobody was as generous as Bünyamin Çelebi,” the article continued, who used his savings to build a 125-foot minaret and was “promptly” elected mayor.

Disparaging media reports also often highlighted the negative consequences of the displays of wealth. In 1971, a fourteen-page Der Spiegel article on guest workers’ vacations reported the emergence of Turkish discourses lambasting guest workers as extravagant spenders who squandered their hard-earned savings on items that were often entirely useless in the hinterlands of Anatolia, where electricity first arrived in the 1980s. “No one knows what to do with a camera and typewriter, so they are sold,” the newspaper wrote. “The electric razor is buried at the bottom of a cabinet – until one distant day, when [the guest worker] returns or his four-year-old son sprouts his beard.”Footnote 108 Even The Sunday Times, a British newspaper with no direct connection to the issue, condemned the “waste of the skilled men who return home”: “Other than a smattering of German and perhaps the money to buy or build a house, possibly a German car or even a German wife, the vast majority have little to show for five to ten years spent in one of the world’s most affluent countries.”Footnote 109 In short, guest workers had filled their homes with fancy stuff that had little other purpose than to collect dust.

Although laden with stereotypes and exaggerations, these media accounts were rooted in reality. In 1971, the same year as the Der Spiegel feature, a governor of the Anatolian province of Cappadocia told a visiting West German official that migration had destroyed local economic life. Not only had it drained the villages of able-bodied workers, male protectors, and individuals able to participate in government, but it had also wrought no economic benefits. “Most of the workers come back without money,” the governor complained. “They just spend it on frivolous things, such as cars, television sets, etc., or even items that do not correspond to their current standard of living and cannot at all be financed by them.” In such cases, the items were sold or abandoned because they could not build or purchase replacement parts. The governor implored the West German official to “advise the workers in Germany to bring such items that can be used for the building of new and income-generating activity,” such as tools and equipment.Footnote 110

Such pleas proved fruitless, however. Nermin Abadan-Unat’s 1975 survey of 500 returning workers in two small Turkish villages confirmed the governor’s complaint that they were not bringing back “useful” items.Footnote 111 Nearly two-thirds brought clothing, tape recorders, and radios, while only 1 percent – a mere seven of the 500 surveyed workers – brought professional tools. One man built himself a five-bedroom house, by far the biggest in the village, which could fit his wife and five children, his son’s wife, and his two grandchildren. While most villagers had austere decor, he adorned his guest room with “modern urban business furniture” and filled the home with accessories: two electric blankets, two lamps, a blender, an electric knife sharpener, five or six clocks, a vacuum, cups and mugs displayed in a grand showcase, a large kitchen table, a washing machine, a food compressor, a tanning bed to provide relief from rheumatism, and – most curiously – a single plastic Christmas ornament hanging from the ceiling. Despite having no electricity, he placed a refrigerator in his bedroom and stored clothing on its shelves.

This conspicuous consumption, which the survey’s researchers called “gaudy” and “superfluous,” was especially offensive not only because its overt ostentation highlighted villages’ wealth disparities, but also because it testified to the migrants’ abandonment of the rural values of hospitality and austerity amid poverty.Footnote 112 At a time when even the poorest families “were suffering for the sake of hospitality” – offering guests refreshments like sugar, perfume, food, tea, and coffee – guest workers spent their money recklessly and ostentatiously. Yet it was not entirely the workers’ fault, the researchers explained: “Workers in foreign countries are accustomed to societies with excessive spending habits. As they walk along the street in the evenings, they are confronted with all kinds of advertisements and shop windows. In these countries, luxury furniture and necessities are exhibited and promoted. On the other hand, to sell to the foreign workers, the owners of stores and shops in these countries also have a tendency to exploit them, even to appeal to their chauvinistic thoughts.” Tantalized by the array of products available at lower prices and buoyed by their higher wages, guest workers “fall into the trap.”Footnote 113

Although the researchers associated these excessive spending habits with the capitalist values of “foreign countries,” both the guest workers and their neighbors described it as a peculiarly German problem. “I’ve been injected with a German sickness. I always want more,” admitted one guest worker, who despite already owning multiple lavish properties in his village planned to open a huge shopping center modeled after the German department store Hertie.Footnote 114 Defensively, another guest worker attributed his spending habits to a broader sense of adopting German culture. “The workers here are slowly beginning to live like Germans,” he contended. “They do not want to live in old houses. Everyone wants to live in a civilized manner, not to work like a machine. Like people. As a result, our spending has increased. Isn’t that our right?”Footnote 115 This praise for “civilized” life in Germany and denigration of “old houses” in Turkish villages, alongside the bold assertation that guest workers were “slowly beginning to live like Germans,” struck precisely at the heart of the issue: after years abroad, guest workers, too, were well aware of their gradual estrangement from Turkish villages and, by proxy, from the Turkish nation. Even if they rejected the derogatory label Almancı, they – to a certain extent – were willing to acknowledge, and even embrace, the notion that they had Germanized.

*****

At age eighty, reflecting on his many years of road trips along the E-5, Cengiz was emphatic: never again would he endure the “crazy” journey, “even if someone offered me 10,000 Euros!”Footnote 116 Fortunately, as for the vast majority of guest workers, Cengiz’s last drive on the E-5 was in the mid-1980s, a time when the significance of the E-5 declined markedly due to the increased expansion, affordability, and convenience of air travel. As Turkey opened its economy to foreign influences in the 1980s, investment in the Turkish tourism industry skyrocketed, and the number of foreign tourists visiting from Germany rose by 12.5 percent annually between 1980 and 1987. By 1994, one-quarter of all tourists visiting Turkey were German.Footnote 117 Competition among firms in the expanding West German and Turkish tourism markets lowered prices and democratized air travel, transforming it from a privilege of the wealthy elite into one that could be enjoyed even by guest worker families. With nonstop flights from Frankfurt to Istanbul taking just four hours compared to three exhausting and dangerous days on the E-5, the preference was clear for many. The long road home had become much shorter, and the Cold War buffer zone had turned into a flyover zone.

Guest workers’ reasons for traveling to Turkey also changed in the 1980s. They increasingly vacationed to Turkey not only to visit relatives but also, as Germans did, to sightsee and take cruises. As one guest worker remarked, “If you want to take a vacation in another country, you would have to pay three to five times as much.” His “pockets full of Deutschmarks,” he added, allowed his family to enjoy much nicer vacations than most Turks could ever imagine.Footnote 118 The number of Turkish tourism firms in Germany also grew markedly, many of them founded by entrepreneurial former guest workers. By 1987, one of the largest was AS-Sonnenreisen, which was founded by Sümer Akat, a former Volkswagen and Ford factory employee, who had begun organizing flights for Turkish mineworkers and later expanded to include German tourists. Just two decades after his menial labor as a guest worker, Akat’s initiative in anticipating the lucrative new market had allowed him to manage 300 employees, several Turkish hotels, and his own airline with regular flights from Düsseldorf, Frankfurt, Hamburg, and Munich to Istanbul, Izmir, Dalaman, and Antalya.Footnote 119

By the late 1980s, the fixation on guest workers’ cars and consumer goods declined in importance as the Turkish government overhauled the country’s macroeconomic system. Not only had guest workers’ friends and families become accustomed to the consumer goods they had brought back over the past two decades, but Turkey’s neoliberal external economic reorientation of the 1980s, which vastly reduced import duties, made foreign products available to a broader stratum of Turkish society.Footnote 120 The migrants recalled that the products they brought with them no longer had the same social cachet. The highly coveted Coca-Cola bottles and Nutella chocolate spread that Murad brought to Istanbul were now available in Turkish stores and no longer made him as “popular” as they had before. And as the economic reforms bridged the rural–urban divide by bringing running water and electricity to even the most remote parts of Anatolia, items like refrigerators, dishwashers, and electric chicken fryers no longer inspired the same awe.