Book contents

- Feral Empire

- Feral Empire

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 The Equine Imprint in Iberian History, Tenth to Fifteenth Centuries

- 2 A Politics of Horses

- 3 The Paradox of Abundance and Illusion of Control

- 4 Indigenous Equestrianism

- 5 Ferality and Breed in “New World” Horses

- 6 Defining Casta and Raza

- Conclusion

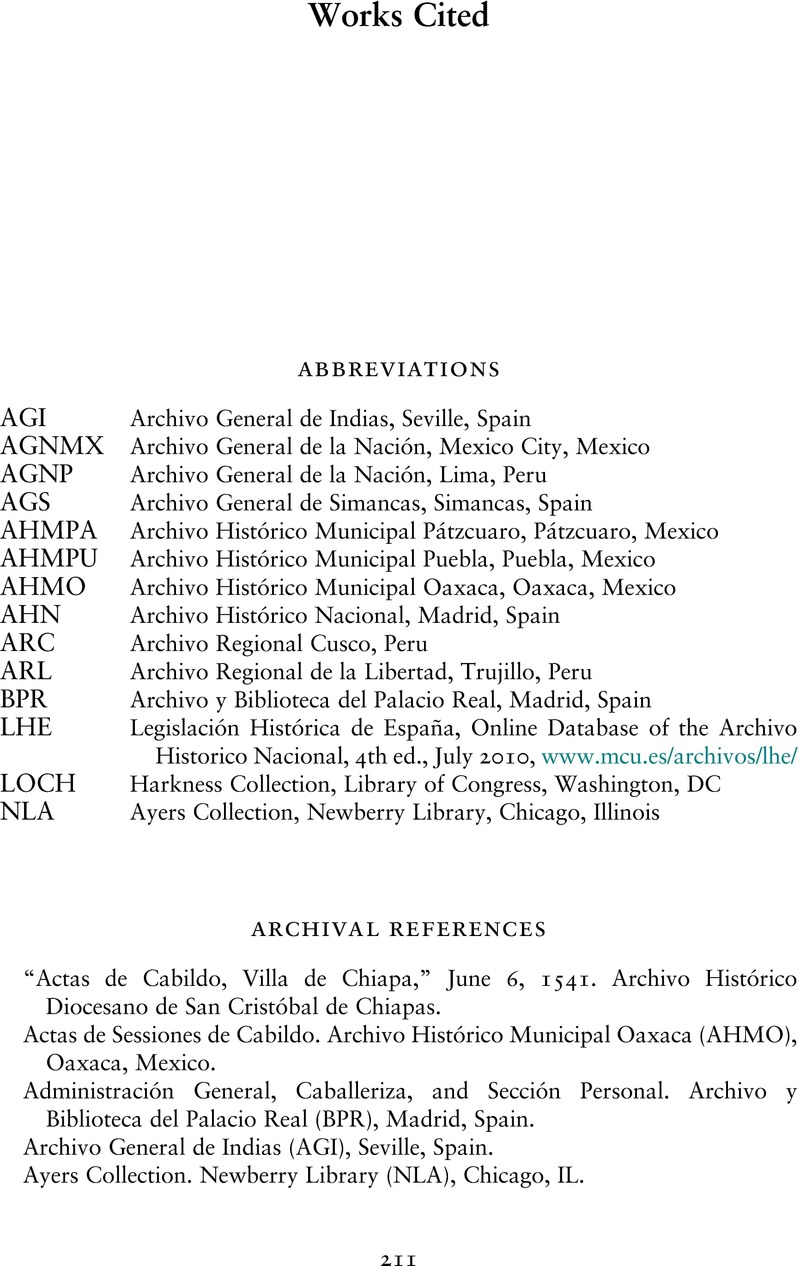

- Works Cited

- Index

- References

Works Cited

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 30 May 2024

- Feral Empire

- Feral Empire

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 The Equine Imprint in Iberian History, Tenth to Fifteenth Centuries

- 2 A Politics of Horses

- 3 The Paradox of Abundance and Illusion of Control

- 4 Indigenous Equestrianism

- 5 Ferality and Breed in “New World” Horses

- 6 Defining Casta and Raza

- Conclusion

- Works Cited

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Feral EmpireHorse and Human in the Early Modern Iberian World, pp. 211 - 232Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2024