This chapter further clarifies the entanglements between popular and imperial discourse at the turn of the twentieth century by focusing on the writings of labor leaders and activists, elite world historical writings, and documents from the British imperial bureaucracy. I show that popular discourses embraced by white labor in the United States and the British settler colonies borrowed from imperial scripts to mark nonwhite workers as a threat. This discourse was thus both imperial and popular, because it enlisted the working class throughout the European and the settler colonial world to defend imperial logics of labor control and settlement while demanding their own enfranchisement. Moreover, while finding channels and institutionalization in emerging national states, white labor enfranchisement demands were part of a transnational emancipatory imagination. These institutional formations emerged from the encounter between capitalists interested in facilitating the mobility of racialized laboring subjects around the globe, elite projects invested in sheltering settler spaces, and white workers concerned with protecting their own labor from competition by excluding exploitable nonwhite workers. Ultimately, white labor’s embrace of racial prejudice and the exclusion of workers of color created segregated labor spaces that fit neatly with both capitalist goals of labor control and settler logics.

In developing the entanglement between empire and popular sovereignty mediated by racial capitalism, this chapter highlights the centrality of migration for prompting the negotiation of tensions in a way that responded to racialized priorities of capitalism and infused popular sovereignty with imperial hierarchies. This makes migration a world historical event, that is, an event with large-scale historical consequences, in this case its prompting of the negotiation and definition of dominant narratives of popular will and self-government. In the process of negotiating tensions between white and nonwhite migrants to the settler colonies and priorities of labor control, ideas of settler self-government consolidated around demands of emancipation grounded in racial hierarchies and redirected anticapitalist critiques in reformist directions. The value of this analysis is to capture a moment of flux in which mobile racialized and white labor reached settler colonies to fulfill different roles within a division of labor dictated by capitalist drives for accumulation. This encounter prompted thinkers, workers, and the British imperial bureaucracy to consider questions of race and democracy, self-government, and profit in ways that shaped the meaning of popular sovereignty and structured the struggles of enfranchisement by white labor. As such, this study makes salient the dynamic and contingent political arrangements that “solve” tensions between capitalist, racial, and democratic logics, as they find new modes of mutual articulation.

Methodologically, the chapter weaves together texts, archives, and regions that are usually approached separately, and grounds the textual analyses in the varied imperial mobilities of the era and the political formations that emerged from these encounters. This historical contextualization illuminates how political practices infuse central political concepts with meaning. The account proposed does not mean to encompass the wide expanse of progressive imperial thought that circulated in this period but it does illustrate the affinities of discourses by imperial bureaucratic elites and working-class intellectuals, on the one hand, and capitalist interests, on the other.

In the rest of the chapter, I first specify how the novel methodological framework of the chapter facilitates the theorization of the dynamic articulation between racism and capitalism, whose existence depends on imperialism and whose shape is partly determined by and underpins popular sovereignty. Then, I analyze writings on labor and world history, which I read jointly with narratives of the British imperial bureaucracy that made sense of the circulation of labor and its curtailment. I connect this conversation to labor politics in England and its white settler colonies or former colonies, and read these events through the prism of popular sovereignty. Having shown the central role of immigration in shaping the intersecting forces of empire, racial capitalism, and popular sovereignty, and how it was also shaped by these forces, I conclude by calling for its historicized reconceptualization within critical theory.

2.1 Method, Migration, and Mobility within Empire

This chapter theorizes the imperial origins of popular sovereignty in British settler colonies and the metropole by focusing on the actual political exchanges, bureaucratic practices, and economic imperatives that shaped moments of enfranchisement. These are “material practices,” by which I mean those actions – including political claims and institutional changes as well as economic and extractive capitalist endeavors – through which empire took shape on the ground and affected the lived meaning of political concepts whose nature concerns political theorists. Even if the existing scholarship reveals that the inherited canon of political thought obscures or disavows a dynamic realm of imperial hierarchies, its focus on absence cannot possibly illuminate this realm, a scrutiny that requires centering material practices to understand how they infused the social and political world in those times, and how they transformed its meaning and trajectory. The entanglement between popular sovereignty and empire means that popular claims were made over the wealth obtained through racial capitalist modes of accumulation enabled by overseas domination. In other words, the material practices of empire and the capitalist wealth it enabled were an integral part of the political world that political theorists interested in empire and popular sovereignty must grapple with.

Onur Ulas Ince’s work on empire and racial capitalism is a partial exception to this trend in that it explicitly takes a “material” approach that centers capitalism conceptually.Footnote 1 Yet the exclusive focus on textual resources – in particular, the theory of colonization of Edward Gibbon Wakefield – directs Ince’s attention to the schemes of governance that Wakefield devised for the emigrating British working class, without following this group into the settler colonies, where they would adopt imperial discourse in their own racialized demands for enfranchisement, which had no place for nonwhite workers arriving on these shores at the same time.Footnote 2

In sum, attention to practice is not simply about applying theory but about correcting the formulation of central political theoretic concepts to account for their (racialized) operation and their entanglement with imperial capitalism. To do this, the chapter jointly analyzes archives, regions, and groups that are traditionally studied in isolation.Footnote 3 By “read[ing] across separate repositories organized by office, task, and function,”Footnote 4 the chapter co-implicates distinct geographical areas and seemingly separate preoccupations and reconstructs a genuinely transnational phenomenon of racially regulated labor mobility and its political ramifications. This reading is organized around mobility as a central feature of empire and an entry point to understanding the political process by which settler colonies recruited labor and enfranchised/excluded it depending on racial markers. In this way, imperial policies of labor control dictated by capitalist needs for labor impacted self-governing colonies and were shaped by (foreign and native) white working classes, who demanded their enfranchisement while rejecting the incorporation of racialized others. Transit, displacement, and groundedness led to entanglements with theoretical implications for how we theorize popular sovereignty but are missed in exclusively textual engagements with these concepts.Footnote 5

By focusing on practices of violence, capitalist labor exploitation, and clashes between different political forces underpinned by ideas about race and labor, this approach necessarily broadens our view spatially and temporally. Spatially, this move refocuses attention onto transnational imperial currents that shape politics in the metropole and self-governing settler colonies who negotiated political demands with imperial capitalist priorities and, in so doing, determined the fate of racialized others. Temporally, this move relativizes the break between empire and self-governing democratic politics, because it shows that the popular movements that spearheaded democratizing trends in the metropoles and the settler colonies were committed to maintaining the subjection of nonwhite subjects and the imperial capabilities of extraction, differing only in the distribution of the gains between capital and white labor. Importantly, this exploration recasts western democracies as imperial products that internalize hierarchical understandings of belonging that fit with racialized capitalist exploitation, on which they depend for their well-being.

With this framework in place, I expand on Chapter 1’s focus on moments of transition and changing forms of subjection and further complicate these processes by theorizing the role of mobility in spearheading instabilities that prompt the negotiation of existing political formations and give shape to new institutions. White workers – transnationally linked through common discourses and networks of solidarity – claimed a right to move and settle, while objecting to the mobility of nonwhite labor, which they saw as threatening. These claims of self-government and demands for a racial regulation of mobility were made at the state level in both settler colonies and the metropole, but converged to create gradated spaces of exploitation globally and within territorial borders. In settler colonies, these struggles cemented the role of the state as the arbiter of working-class struggles and as the gatekeeper of the land, naturalizing its expropriation from Indigenous peoples.Footnote 6

These processes were not independent of the experience of the emancipation of Black slaves in the United States, which was understood as a “failed” incorporation into a white polity and loomed large in how elite writings and demands for white enfranchisement dealt with nonwhite newcomers in Australia, Canada, South Africa, and the United States. As shown later, these connections and separations resorted to notions of “popular sovereignty” to create what is known today as “immigration control,” but can more accurately be characterized as imperial labor control in the service of racial capitalism. It is in these interconnections and transitions that I continue to track the imperial character of our present institutions.

Attending to mobility and emerging tensions shows that the global British imaginary and common culture that scholars have reconstructed developed neither just at the elite level nor in isolation from the native and nonwhite groups it excluded,Footnote 7 but very much through the encounters and the actions, negotiation, and arguments about these exclusions. The expansive view proposed here shows that differently racialized groups in transit shaped each other and were shaped jointly by capitalist imperatives, elite priorities, and grassroots movements for white labor enfranchisement, three parties that often found themselves at odds. While capitalists were invested in facilitating labor control by moving laboring subjects around the globe and curtailing their mobility upon arrival, elite projects were invested in sheltering settler spaces, a concern echoed by white workers invested in protecting their own labor from the competition of exploitable nonwhite workers. Ultimately, white labor’s embrace of racial prejudice and the exclusion of nonwhite migrants cemented subject constructions and segregated labor spaces that fit neatly with racial capitalist goals of labor control through differentiation and separation.

All three actors – imperial capitalists, intellectual elites, and white workers – relied on racial arguments about the ability to perform disciplined, self-directed work and/or partake of self-governing, civilized societies, even if they did not always pull in the same direction. While white workers’ demands were for local state-based restrictions on the entry of nonwhite foreigners, their narratives were part of global imperial narratives and operated in transnational solidarity with other white workers. The state institutions that emerged imitated the imperial racial regulation of mobility while materializing them through self-governing rules, which eventually congealed and hid their imperial and transnational origins.

2.2 Racial Capitalism and Mobility within Empire

In his Inaugural Address to the International Workingmen’s Association in 1864, Marx argued:

In all countries of Europe it has now become a truth … only denied by those whose interest it is to hedge other people in a fool’s paradise, that no improvement of machinery, no appliance of science to production, no contrivances of communication, no new colonies, no emigration, no opening of markets, no free trade, nor all these things put together, will do away with the miseries of the industrious masses; but that, on the present false base, every fresh development of the productive powers of labour must … deepen social contrasts and point social antagonisms.Footnote 8

Here, Marx notes two transnational dimensions of capitalism. First, capitalist exploitation and dispossession reached abroad through the acquisition of colonies. Second, it required the expulsion (via emigration) of redundant sections of the population,Footnote 9 which in turn populated British settler colonies in North America, Oceania, and South Africa. Moreover, Marx notes that capitalism has no national loyalties; imperial exploits, along with other techniques to increase productivity, did not aim to relieve the miseries of European workers, and did not in fact do so. Thus, as Marx notes in closing, before demanding proletarians of all countries to unite, the success of the working classes will come out of “combination and knowledge” and from standing “firmly by each other.” Failing that, any efforts must collapse due to the “common discomfiture of their incoherent efforts.”Footnote 10

The story that this chapter tells is one of discomfiture and incoherent efforts, organized along axes of race that Marx did not examine, but that would prove determinant for the failure of projects that could oppose imperial capitalism in its transnational form. Even in his limited internationalism, Marx’s hopes that the early signs of British working-class internationalism – at play in its support for Lincoln and the struggle of Poland against Russia – would prevail were unwarranted.Footnote 11 This internationalism, which had thrived during Chartism’s cooperative work among British and Irish workers and would be sustained by radical artisan groups who actively debated imperial questions, would wane as the century progressed.Footnote 12 It would give way to a tamer trade unionism, the depoliticization of workers’ social activities, and, ultimately, an embrace of imperial successes, represented by the euphoria around the end of the siege of Mafeking, in the Second Boer War (1899–1902), which radical workingmen’s clubs joined in 1900.Footnote 13 The war had split the socialist Fabian Society, between those behind S. G. Hobson and Sidney Olivier and a branch that followed George Bernard Shaw. The former maintained that the aim of the Boer War was to establish supremacy over the natives and that imperialism as a whole detracted the British government from worthy domestic purposes, such as the establishment of an “industrial democracy.” Shaw, on the other hand, was invested in the protection of British miners and the transfer of mining to public control to support an imperialism for the public interest. The Society ultimately did not take a position on the war, though most of its members sanctioned some form of imperialism.Footnote 14

These evident divisions among progressives by the end of the century are predicted by Marx’s increased pessimism about the unity of the working class, expressed only six years after the 1864 address, in his comments about the divisions between Irish and British workers. He criticized the latter’s self-conception as members of the “ruling nation,” one fueled by “the press, the pulpit, the comic papers, … [i.e.,] the means at the disposal of the ruling classes.”Footnote 15 These imperial alignments turned the British worker into “a tool of the English aristocrats and capitalists against Ireland, thus strengthening their domination over himself.”Footnote 16

Marx points to the important – and still pressing – problem of working classes’ cooptation by imperial capitalist projects, but he also misses the point that alongside white emigrants, Indian and Chinese subjects had circulated within and beyond the British Empire since the early nineteenth century and had joined freed slaves and native labor within the empire.Footnote 17 This does not mean that differentiations among white workers were inconsequential – as Marx’s discussion of Irish labor shows – or that these differences were not racialized. There is a long trajectory of European racialism, comprising enslavement regimes (of Slavs, Greeks, Russians, among others), the devaluation of European peoples identified with the “Orient,” the drawing of the European bourgeoisie and proletarians “from particular ethnic and cultural groups,” and the racialization of white workers through slave analogies.Footnote 18 In the United States, white workers’ skills and wage differences were exploited by employers for the purposes of labor control, with Eastern European migrants conscripted to break strikes or counter unions’ threat to take management control.Footnote 19 Ethnic differences, moreover, were often exploited to lower labor clout, by creating competition among different ethnic groups or mixing ethnicities on the shop floor. These maneuvers interacted with technological change and allowed for workers to be replaced by unskilled labor, predominantly from Eastern Europe. For example, 80 percent of “common laboring jobs” at the former Carnegie Mills in Allegheny County were filled by Eastern Europeans by 1907.Footnote 20 Further illustration of the distinct character of white ethnic gradations vis-à-vis the white/nonwhite divide appears in South African debates about Chinese indenture. Debates about mining acknowledged the alternative of relying on “mean” or “hardy” whites such as Swedes, Italians, Lithuanians, or Russians, but took these groups to be undesirable in comparison to the acknowledged equality of the Dutch and English “races.”Footnote 21

Yet the competition of these groups, while “unwanted,” was threatening precisely because, unlike Chinese indentured migrants, other white workers could and would demand salaries closer to those earned by Dutch and English workers and could not be disciplined or segregated like the Indian and the Chinese were. Thus, the subtle hierarchies within whites do not diminish the qualitative and quantitative break of transatlantic slavery in this genealogy. Similarly, while an array of distinctions among different white ethnicities were discussed by eugenicists and exploited by employers in the United States and the settler world, the racial distinctions, practices of separation, and intensity of exploitation between whites and nonwhites were starker and more persistent, and merit particular attention. Notably, while ethnic whites in the United States were allowed to fill low skilled positions in factories that incorporated new machinery, nonwhite workers were confined to strenuous bodily work in the fields, mining, or railway construction, pointing to the stricter labor segregation and exclusions affecting these groups. This was at play in occupations like crane operation, which was an easily learned skill but it “long survive[d] as a craft job preserved for white workers.”Footnote 22

Nonwhite labor flowed into the settler colonies via indenture programs that became prominent after the gradual abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1834. Labor imports, regulated by the Court of Directors of the East India Company and the British Parliament, were sought to control newly freed African laborers in the Caribbean.Footnote 23 While indentured labor – recruited predominantly from British India – was defined as “free” labor, all recruited individuals traveled as a group, contracted some form of debt, and/or were attached to an employer upon arrival.Footnote 24 Moreover, while regulations existed to protect the emigrants, reports abounded of recruitment through “fraud, deception, and kidnapping.”Footnote 25 Finally, findings from official investigations indicated that indentured workers were subject to high death rates and corporal punishment if they tried to escape.Footnote 26 Attesting to employers’ motivations, many proposed schemes were rejected for containing conditions considered “even less equitable than [those] of slavery itself.”Footnote 27 In the face of loud protests from the Indian Colonial Office and anti-slavery activists, the program was suspended only a year after its official sanctioning; it was allowed again in 1843 with conditions less favorable to planters and shorter contracts, which were expanded to five years only in 1860.Footnote 28 Even after reforms and the establishment of offices to protect workers and control employers, reports noted the abundance of disease in waiting camps and vessels carrying indentured laborers, poor living conditions, and the use of criminal prosecution and hard labor as punishment for labor disputes.Footnote 29

While labor imports from India were banned, colonial secretary Lord Stanley expressed no reservations about Caribbean planters recruiting from Chinese territories under British control. He noted that “emigration was … routine among some Chinese communities,” making protocols addressing fraud and abuse unnecessary.Footnote 30 Thus, throughout the nineteenth century, imperial authorities scrambled to “solve” the post-emancipation problem of labor control by transporting laborers from around the empire to provide planters, mining interests, and infrastructure developments with a submissive workforce. In the process they deployed racial discourses that assigned to different groups particular propensities to work, obedience, and adaptability to “free” contracting. Just as arguments about the laziness of freed slaves and their inability to honor contracts had been deployed to justify importing Indian labor to the Caribbean in the 1830s, planters – likely in the face of desertions, strikes, and the lodging of complaints by indentured labor – turned to argue that Indians, while steadier workers than Afro-Caribbeans, were also “avaricious, jealous, less robust, and given to killing their women, not to mention dishonest, idolatrous, [and] filthy.”Footnote 31 In comparison, recruiter James T. White reported from China that Chinese workers were alive to the needs of authority and generally “tractable and manageable,” strong, tough, and “not averse to foreigners.’”Footnote 32 Halfway through the nineteenth century, Chinese laborers started reaching North America and Australia in greater numbers, fleeing the opium war and political instability in China, and spurred by the discovery of gold in California in 1849, in New South Wales in 1851, and in British Columbia in 1858.Footnote 33 The construction of the intercontinental railways in the United States and Canada brought more Chinese laborers from Guangdong and Hong Kong, respectively, who arrived with pre-paid contracts and free passage and the official imprimatur of the Burlingame Treaty for temporary migration, signed in1868 by the United States and China.Footnote 34 In the second half of the nineteenth century, Australia received significant numbers of Chinese migrants and arranged with the India Office to recruit indentured workers from India.Footnote 35 South African colonies similarly resorted to labor recruitment programs that brought Indians to work in sugar plantations in Natal, and, later, Chinese in mining in the Transvaal.Footnote 36

Different forms of labor mobility and immobility awaited white workers. Liberal intellectuals such as Edward Gibbon Wakefield were concerned with excess labor in the metropole (which brought risks of unemployment, poverty, and labor militancy) and the dispersal of capital and labor in the settler colonies, and saw emigration from the metropole as a solution to both problems.Footnote 37 Accordingly, the New Poor Law Act of 1834 allowed parishes to raise or borrow money to support the emigration of its willing members, who joined earlier programs of child emigration, convict labor, and voluntary migrants from England and elsewhere in Europe. Altogether, upwards of 55 million migrants left Europe for the Americas between 1846 and 1940, while others left for Australia, in various capacities, starting in the eighteenth century and picking up pace in the second half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 38

By the end of the nineteenth century a backlash against nonwhite migrants had set in. In 1893, Charles H. Pearson – an Oxford-educated historian, King’s College professor, and recent emigrant to Australia – published National Life and Character: A Forecast, which prophesied the decline of western civilization in parallel to the advance of Asia, in particular China.Footnote 39 The work was inspired by two realizations. First, Pearson noted, “America was filling up,” making less plausible the use of British emigration as an escape valve for working class organization and fueling a tendency toward state socialism in the west.Footnote 40 Second, Pearson noted the breakthrough of nonwhite peoples onto the world stage. This was not merely hypothetical for Pearson, who witnessed the Chinese empire’s exchanges and demands regarding its subjects in Australia.Footnote 41 Pearson contested prevalent conceptions of world history by acknowledging nonEuropean countries’ political agency, even as he reproduced a number of dictates of racial science, such as the inadaptability of the white race to tropical climates, the barbarism of certain peoples, and/or the inferiority of Indigenous Central Americans.Footnote 42 It was the latter, among others, that he foresaw being ruled by the Chinese, an estimation informed by both the difficulty of white settlement beyond temperate zones, and the experience of Chinese settlement in other countries. He cited the Straits Settlements as an example of the spread of the Chinese, noting that they amounted to half of the population in Singapore and Perak (Malaysia), and that the Malay could not hold their own against them.Footnote 43

Moreover, Pearson continued, the Chinese were “tolerably certain” to gain the upper hand in the long run, given their superiority in numbers vis-à-vis the Malays (“sixteen to one”), and their superior industriousness and organization in precluding competition. If in fifty years China had become one of the great world powers, he inquires, would “the larger part of Borneo … still be a dependency of the Netherlands?” or would this island “have passed, by arms or diplomacy, into the possession of China?”Footnote 44 If the Chinese had not become a power in the Australian continent despite their growing numbers in Victoria, Pearson explains, it would only be because of the “vigilant opposition of the Australian democracies.”Footnote 45 Pearson saw whole areas of Central and South America “north of Uruguay” (where the aboriginal race – decimated by misrule and the half caste – “is fit for nothing but servitude”Footnote 46) as open to the control of “Chinamen” with a footing in Peru, or by “coolies … working profitably in British Guiana.”Footnote 47 Pearson thus concludes that a strong presumption exists for a people of such enormous natural resources as the Chinese, that they will eventually “overflow their borders, and spread over new territory, and submerge weaker races.”Footnote 48

Pearson’s book caused a stir in academia and political circles. Theodore Roosevelt reported directly to Pearson of the “great effect” his work was having in the United States, and Prime Minister Gladstone was reportedly “full of Pearson’s book.”Footnote 49 The National Character influenced nativist American tracts such as Madison Grant’s The Passing of the Great Race (1916), and The Rising Tide of Color (1920), by Lothrop Stoddard, who characterized Pearson’s book as “epoch-making.”Footnote 50 Pearson’s book transformed the victorious Teuton marching triumphant through world history into a narrative of the white man under siege, one that would justify a host of exclusionary immigration and domestic measures securing “white countries” around the globe.Footnote 51

2.3 Empire, Settlement, and the People

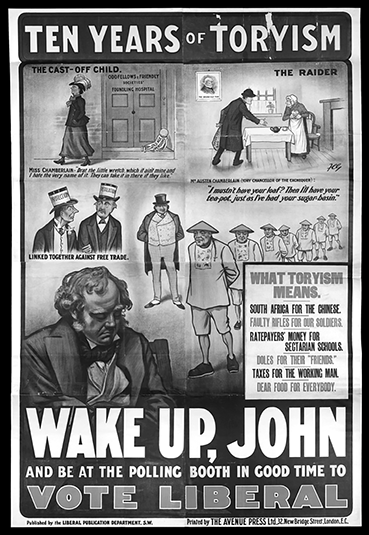

Elite discourses of threat had a popular counterpart in the anti-immigrant claims by workers in the British colonies who refused to compete with “free” workers of color.Footnote 52 Australia and most colonies in South Africa, for example, already mandated nonwhite guest workers to return at the end of their contracts and subjected them to tight restrictions while in the country. These racialized discourses were also prominent in the metropole, as the British general election of 1906 illustrates, with the historic defeat of the Tory government of Arthur Balfour in an election that revolved around the Second Boer War. In this election, the recruitment of Chinese indentured workers by mining companies in the war’s aftermath figured prominently, a phenomenon dubbed “Chinese slavery” by abolitionists and humanitarian activists.

The buildup to the Second Boer War mobilized British ethnic feeling both in the South African colonies and the metropole by highlighting the vulnerable position of British subjects in South Africa.Footnote 53 The diamond and gold wealth discovered in the 1860s and 1880s in Kimberley and the Witwatersrand had renewed Britain’s hopes of turning South Africa into a destination for English emigration. Such a project envisioned its gradual transformation into a unified self-governing colony in the style of Australia, Canada, and New Zealand.Footnote 54 Through the promise of wealth through emigration-cum-settlement, political elites implicated the British working class in the war and the policies toward Chinese migration. The victory of the Liberals in the 1906 election and the historic Tory upset were based on a campaign that tied Toryism with a “South Africa for the Chinese” policy, a platform shared with the Labour Representation Committee (later the British Labour Party)Footnote 55 (Figure 2.1). In particular, British trade unionists relied on anti-slavery rhetoric to condemn the conditions of Chinese labor. Yet, in this condemnation, those enslaved received no sympathy, which instead went to “British and South African white workers,” whose rights to welfare and employment were threatened by Chinese competition.Footnote 56

Figure 2.1 Artist Unknown. Poster produced by the Liberal Party for the 1906 General Election campaign: “Ten years of Toryism.”

The tensions between race, mobility, capitalist profit, and the settler project came into relief in turn-of-the-century South Africa. The discovery of gold had turned this colony from a strategic port on the way to India into a crucial source of the precious metal needed to maintain the supremacy of British sterling.Footnote 57 But the strategic importance of gold, and the urgent need to secure the labor to extract it, had to be reconciled with the goals of white settlement, which entailed establishing British dominance in relation to Boer settlers and attending to the anti-Chinese demands of white workers in the metropole and the colony.

According to a report that circulated among British imperial bureaucrats, opposition to Chinese labor imports in the Transvaal was associated with the fear that they would “swarm over the whole country in enormous numbers, invading every trade and acquiring a permanent hold of the land.”Footnote 58 A communication from South African leaders to Viscount Alfred Milner (British governor of the colonies of Orange and Transvaal), including soon-to-be Prime Ministers Louis Botha and Jan Christian Smuts, put a popular spin on this objection. They claimed that introducing “Asiatic” labor without consent would be fatal and looked upon as “a public calamity of the first magnitude,” because it would “prevent this from ever becoming a white man’s country” and exclude the native population from participation in the development of industry.Footnote 59

Interestingly, those who favored the importation of Chinese labor to the Transvaal in no way departed from basic settler assumptions. For proponents of Chinese labor, the dignity and superior racial status of whites required the temporary importation of indentured laborers, who would be repatriated after fulfilling unskilled mining work or until native labor could be relied upon again.

The strenuous work that whites could not perform for either “climatic and physical reasons,” the simple taboo on performing demeaning work, or the fact that their wages made their employment in unskilled positions unprofitable, was required to return the mining industry to health and fuel economic activity that would benefit white workers.Footnote 60 Thus, the settler logic relegated African natives to physically intense jobs without which gold extraction could not be made profitable; for this, they relied on taxes that pushed natives into selling their labor and, failing this, enlisted Chinese indentured migrants to be returned at the expiry of their contracts. White settler jobs were thus cordoned off, just as the land they settled was protected by the creation of native reserves, pass laws, and ordinances that separated African, Indian, and Chinese laborers from whites’ places of residence. Indentured work “failed” only when nonwhite migrants remained in the territory and accessed “certain classes of white trades” and political rights, as happened in Natal.Footnote 61 The established division of labor, assigning “brain work” to whites and “brawn and spade work” to “black or some coloured race,” reinforced racial theories that established the superior status of the white race over all others, and required a wage to match “the higher scale of civilization and standard of living” that laboring Englishmen, however despised at home, achieved by merely landing in South Africa.Footnote 62 Restrictions applied to nonwhite arrivals and nonwhite residents curtailed this same upward mobility and political enfranchisement for everyone else. The connection between wage and stage of civilization was by no means a new or isolated claim; Marx himself casually tied together the “necessary requirements” of workers with the level of civilization in his discussion of the sale and purchase of labor power.Footnote 63 This feature of labor power – which sets it apart from other commodities – is what Marx calls the “historical and moral element” in the determination of its value,Footnote 64 and reappears racialized in the debates reproduced here to justify the racialized threat that nonwhite arrivals posed to white settlers-qua-workers. This metamorphosis of the “historical and moral” into the racial is clear in how white workers could leave behind their wretched conditions in Europe, while racialized immigrants remained tethered to their supposedly inferior “scale of civilization” indefinitely. The grounds of this dispute were, in turn, the land dispossession of Indigenous peoples, whose “civilization” made them unfit to control land, given their inability to work it in the destructively productive manner sanctioned as proper by European modernity.

The division of labor which required the physical exploitation of Black and brown workers was entwined with the production of racial difference and the protection of white settlers, who appropriated the most valuable jobs in the mining industry, in addition to the most valuable land. But the exclusionary impetus among white workers had to be modulated by the interest of British capital, which depended on South African mining, leading a member of Parliament to claim that taking away Chinese labor from the Rand gold mines would be “an act of treachery to the Empire itself.”Footnote 65 Thus, the racist construction of the Chinese as ready for harsh and poorly paid labor served to prop up South African mining cheaply after the war, a position solidified by the popular mobilization of white workers against them; this mobilization failed to exclude them altogether, but demanded and embraced measures to enforce these workers’ precarious, exploitable position and their residential and labor segregation.

A similar privileging of white workers’ well-being and an implicit settler orientation characterizes the writings on Chinese emigration by prominent British labor leader and intellectual Henry Mayers Hyndman, credited with building “what there was of a Marxist movement” in England, including founding and dominating the first 1880s Marxist organization (the Social Democratic Federation), the forerunner of the Communist Party.Footnote 66 In his volume The Awakening of Asia, Hyndman devotes a full chapter to the question of Chinese emigration. He acknowledges the racial motivations of anti-Asian feeling in the United States and Australia, but considers wage competition an acceptable ground for restricting their settlement in countries “already partially peopled, not by Malays or other Asiatics, but by men of European Race.”Footnote 67 This is because he thinks that it is beyond dispute that “under capitalism, competitive wagedom and production for profit, the European and American workers cannot hold their own against the Mongolian toilers.”Footnote 68 Hyndman explains that the transition toward the “general organisation of industry upon the basis of co-operation instead of competition” cannot advance fast enough to handle the problem of Asian labor competition with white workers before “it is forced upon the world on a vast scale.”Footnote 69

Hyndman was frustrated with discussions of Chinese migration in international socialist fora and in Special Commissions on which he served. Hyndman thought the majority exhibited great ignorance about the matter and were not inclined to “look facts in the face” when they conflicted with “universal humanitarian theories,” making the reports presented practically valueless. The facts, according to Hyndman, were that European workers were not yet competent to handle “the whole of this immigration problem” and that American and Australasian workers were, mostly, bitterly prejudiced.Footnote 70

Thus, Hyndman acknowledges and implicitly condemns racial prejudice (with some equivocation on whether it is justified against the Chinese rather than the civilized Japanese).Footnote 71 However, he demands that the facts of Asian superior toil and the difficulty of addressing the competition for labor in a society that falls short of cooperativism take precedence over universal principles. In fact, he does not even specify these universal principles, socialist or otherwise. Hence, as in the South African case, the discussion is centered on the grievances that befall white workers as a consequence of Asian labor, rather than on those that affect Asian workers, including the unpacking of assumptions regarding their work ethics, surely due to vulnerable legal status, discrimination, and exploitation rather than a natural propensity toward toilsome work.Footnote 72

The world historical conceptions of Asian threat, the Chinese slavery debate, and white labor’s discourse about nonwhite workers reveal that race, space, and capital figured prominently in turn-of-the-century global discourse. This discourse was clearly imperial, but it was also popular, because it reached and enlisted the white working class throughout the United States, England, and white settler colonies, and became part of their emancipatory imagination, binding them together “into an imperial working class.”Footnote 73 This transnational working class linked British trade unionists and socialists with white workers in South Africa and “crisscrossed the western U.S.-Canadian frontiers to engage in riots, lobby for immigration restriction, and establish anti-Asiatic organizations,” animated by a broader pattern of racialization drawing from linkages between racist proletarian movements in the United States, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and the British metropole.Footnote 74 Labor organizers echoed the language of competition that displaced the injustice of capitalist arrangements and instead centered their critique on capitalists’ recruitment of Chinese labor. This was expressed crisply by British Columbian M. A. Beach, who, speaking at the Washington Federation of Labor gathering in the United States, celebrated working class successes, such as increasing the Chinese head tax from $50 and $500, but encouraged his comrades not to rest until “we get total prohibition of the yellow evil.”Footnote 75

While the multiple acts restricting and ultimately banning Asian migration to the United States that emerged in this political climate are relatively well known, the Canadian efforts at restricting Indian migration and taxing Chinese entrants are less so. Yet even if during this period their common belonging to the British Empire prevented an outright ban, Canada creatively restricted Indian migration.Footnote 76 Debates between 1906 and 1915 culminated in the creation of a passport system for the British empire and made embarking on a journey in any British India port without a such a document a crime, breaking with the principle of free movement and equal subjecthood within the empire.Footnote 77 Thus, settler and former settler colonies were of one mind with US eugenicist Stoddard, who remarked that what concerned the Japanese in California also held “for all types of Asiatic [elsewhere in] our Union, in Canada, in Australia, in South Africa and in every other region of white settlement where the man of color attempts to penetrate.” This, “a true world-problem,” he argued, “must be considered in this broad way.”Footnote 78

The language of self-government and democracy figured prominently as the British bureaucracy coordinated and made sense of the demand for immigration restrictions within the empire. In a letter to the secretary of state for the colonies, responding to a complaint by Sikh groups about restrictions on entry to Western Australia and curtailed access to work permits, the governor of that colony argued that, regardless of the views of the government, it could not “retain its position in this Democratic Country, and advocate an equality of rights to coloured people.”Footnote 79 The “democratic” conception of rule is clearly distinguished here from a substantive commitment to equality. The letter then states that Western Australian voters do not take into consideration “what the obligations of the Mother Country may be to the Indian Subjects,” but “the competition of a Race or Races who can and will, owing to their different conditions of living and frugality, undersell them in production and labor.”Footnote 80 The latter argument connects the popular will to the well-being of white workers, who are entitled to demand that the polity excludes those who are exploited, for they offer a competition that less “frugal” workers cannot beat. As with other instances of narratives of threat, these claims run counter to the fact that the measures defended – like banning nonwhites from certain trades – in fact produced the frugal workers that would then be deemed threatening.

However, the opposition between the self-governing colonies and the imperial government’s “obligation” to protect Indian subjects is not so pronounced as the exchange suggests. In a later exchange regarding the Union of South Africa, the Earl of Crewe (secretary of state for India) states the point to Viscount Gladstone (governor of the General Union of South Africa) by acknowledging that while His Majesty’s Government raises strong objections to “the prescription … of the inhabitants of one part of the Empire by another,” it also fully recognizes “the right of a self-governing community such as the Union to choose the elements of which it shall be constituted.” He concludes by noting that it is not their desire to press the government to admit immigrants whom the people of South Africa are resolved to exclude.Footnote 81 Here, the British crown relies confidently on the language of constitution of a people as having to do with its (racial) “elements” and acknowledges this as a legitimate feature of white self-governing polities, even though it contradicts the formal principle of equal subjecthood.

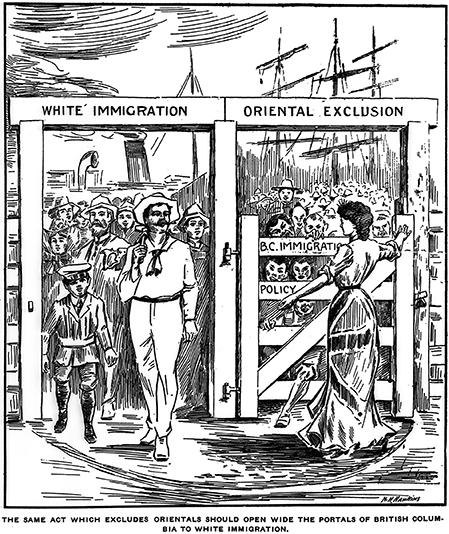

In these debates, which are formally concerned with immigration, the distinctions cited in favor of exclusion by intellectuals, labor, and the imperial bureaucracy were strictly about race, rather than foreignness. Claims by labor groups followed not from longstanding membership in the polity but from whiteness. These claims, moreover, were made in dialogue or solidarity with white working classes in other colonies and the metropole, who saw emigration and settlement as a path to upward mobility. Understandably, then, restrictions on Asian migration co-existed with incentives and desires to foster European white migration (Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2 N.H. Hawkins’ cartoon in the Saturday Sunset, August 24, 1907: “The same act which excludes orientals should open the portals of British Columbia to white immigration.”

The salience of race, rather than membership, in motivating labor hostility was evident in the United States, where racial animosity also pitted white workers against Mexican-American and Black workers who were citizens. Du Bois’s critique of Democrats in Reconstruction reflects this when he notes that California and Washington state opposed the franchise of Black, Indian, and Chinese groups in 1868.Footnote 82 Moreover, immigrants from Mexico, while foreign, were exempted from the quotas established by the anti-Asian laws in order to provide the labor needed after the ban on Asian migration led to a shortfall.Footnote 83 Despite this exemption, this group was the subject of widespread racism and targeted by border policing and other forms of surveillance in ways that their foreign white counterparts were not.Footnote 84

It follows that the control of nonwhite immigration was simply one among many mechanisms of labor regulation and dispossession of racialized others that privileged the well-being of white groups and their access to land. In the countries under study, land dispossession and/or racial labor regulation targeted African natives in South African colonies, Indians in Natal, Indigenous, Black, and Mexican-American groups in the United States, and Indigenous groups in Australia and New Zealand, all groups whose subjection could not be ensured through migration control. These internal racial exclusions were also supported by white groups, and the reasons for the avowedly threatening character of these racialized groups were continuous with those to restrict migration. A racial capitalism approach, which takes the differential and more intense exploitation of racial others as typical of capitalist forms of reproduction through the exaggeration and racialization of difference,Footnote 85 clarifies that migration control constitutes no realm of its own but a racial technology akin to many others.

Not only was race the overarching axis of exclusion across many domains, but the racialized discourses were also continuous throughout imperial republics, self-governing units, and the British metropole and sought to order all races, not just Indians and Chinese. Indeed, much of the debate on the threat of Asian migration in the settler world was inspired by the historiography of the “failed experiment” with racial equality in the post–Civil War United States.Footnote 86 This question also figured in the discussions about white emigration from Britain, leading Wakefield to judge British emigration an incalculable gain for Americans, who were “cursed with slavery.”Footnote 87 This “curse” was also discussed in US labor circles. Samuel Gompers, the English-born US union leader and founder of the American Federation of Labor, argued that the association of manual labor with “those who were formerly slaves,” who were placed below white workers in terms of worth and dignity, operated against efforts “to secure social justice” by law or labor organizing.Footnote 88 David Roediger captures this dynamic when he identifies whiteness as the identity that allowed US white workers to respond to fears of dependency on wage labor and to the discipline of capitalist wage work, but I show that these dynamics are neither strictly national nor limited to anti-black racism.Footnote 89 In fact, Gompers moves on to discuss labor competition in relation to the annexation of the Philippines, which would have “the Chinese, the Negritos and the Malays coming to our country,” or “Chinese coolies” from the Philippines swarming “the United States engulfing our people and our civilization.”Footnote 90

In sum, the paths carved by mobile colonial subjects, and the popular, discursive, and administrative justifications for restricting nonwhite migrants fueled a conception of proper global mobility, newly regulated by self-governing colonies and sovereign states that absorbed rather than abandoned imperial logics of mobility and white settlement. The very view of settler colonies as more advanced democratically and socially progressive coexisted without contradiction with their presumed right to govern inferior others, a position publicly endorsed by Roosevelt, Alfred Deakin, and many others.Footnote 91 In this sense, the control of nonwhite migration was at once imperial, colonial, and popular, in that it presumed a collective agreement to displace Indigenous peoples and populate these areas with white European subjects while conscripting nonwhite labor for strenuous jobs, or excluding them altogether when they attempted to enter the territory.Footnote 92 Racial discourses of labor competition grounded the popular justification for exclusion and the performance of settler self-government that so enthused nineteenth-century liberals.Footnote 93 Throughout the settler world, the regulation of mobility and establishment of sovereign border controls was less about foreignness and more about finding institutional proxies through which to racially shape population inflows and enforce a profitably precarious status for racialized others, while protecting the well-being of white subjects in “white countries.”

In this sense, the “present everydayness” character of settler colonialism revealed itself as not only the continued occupation of Indigenous land and expansion of its oppressive logics to other subaltern subjects that Chikasaw scholar Jodi Byrd recovers,Footnote 94 but also the continued recruitment of settler subjects (European migrants) into the project. Following Byrd’s warning about how struggles for hegemony within and outside institutions may make us lose sight of underlying structures of settler colonialism,Footnote 95 my focus is not on the exclusion of racialized others from a normalized settler-citizen status, but on how white subjects arriving from Europe enthusiastically joined the settler project and called it democracy. These enthusiastic joiners solidified the territorial character of settler dominions, cordoned off nonwhites from the area through land dispossession, and sustained white life through the forced labor of workers of color, facilitated through the strategic establishment of different governmental technologies that produced subjection and vulnerability.

Overlaying and hiding this structure, discourses and actions by the white working class successfully posited a “people” that encompassed foreign and native whites and enacted a particular shape and content of popular sovereignty, while constituting their demands as “the people’s will.”Footnote 96 Although the democratic legitimacy of such a declaration is dubious, it is nonetheless a popular claim to authority, an attempt at “racialized people making” that provided closure in moments when the boundaries of the polity were contested.Footnote 97

The instance of people-making depicted in this chapter, however, indexes the notion of popular sovereignty in two further ways. First, it highlights the transnational affinities of movements that enlisted states as protectors of white well-being – an early instance of “think global, act local.” Second, it illustrates that popular sovereignty in self-governing white spaces was entangled with empire, in the sense that it continued the imperial mode of governance of labor mobility, this time through immigration regulations that protected and solidified settler colonialism. This brand of popular sovereignty relied on selective modes of sharing and concentrating power, and was built on differentiation and selective inclusion and exclusion in modes typical of empire and its racial capitalist mode of extraction.Footnote 98 In this sense, popular movements demanding enfranchisement in the early twentieth century should be seen less as self-determining units differentiating themselves against other units than as processes of decentralization of imperial governance through its absorption by settler states. The same can be said of the immigration regimes that ensued from these emancipatory struggles, which were imperial institutions through and through, and whose goal was to exclude racialized others.

In this equation, people-making and critique of white workers’ exploitation, on the one hand, and the element of racism, on the other, were inextricably entangled.Footnote 99 This undermined the democratizing and anticapitalist credentials of this activism. Yet it would be incorrect to consider the demands of white labor as necessarily contradicting the priorities of imperial labor control, because the differential commodification of labor needed not erode the standing of privileged wage labor and may have even safeguarded the well-being of this group.Footnote 100 Tragically, this development displaced more structural challenges to capitalism and its reliance on racially gradated regimes of exploitation.

2.4 Critical Theory, Migration, and the Question of Empire

The proposed account suggests that imperial mobility was organized to differentially govern subjects in order to create a racially exclusive people that relegated other groups to the margins, thus facilitating more intensive accumulation, which enabled the expansion of well-being among white groups. In contemporary political theory, mobility is theorized under the category of “immigration,” which is studied either as a realm of its own by political philosophers or in an ad-hoc manner prompted by worrying political developments by critical theorists. In the former case, which I analyze at greater length elsewhere,Footnote 101 migrants are taken to be outsiders whose treatment ought to be assessed via a variety of normative principles, including territorial rights, freedom of movement, or national culture. But in considering immigration control a legitimate attribute of (popular) sovereignty or contesting this legitimacy, these accounts fall for the disappearing act performed by the transfer of the functions of imperial labor control to white, self-governing, settler colonial states. As such, they debate imperial remnants that racially segregate and control labor as an ahistorical realm that we can judge via ethical principles while avoiding engaging with its genealogy. In the latter case, migration has been addressed by those interested in the growth of support for right wing, xenophobic leaders and the democratic erosion that sometimes accompanies this trend. Yet critical theorists seldom make migration itself a topic worth theorizing on its own, assuming instead that it is either one of the “flows” characteristic of globalization, or the target of anxiety provoked by the precarization of increasing portions of the white working class.

Wendy Brown, for example, takes “immigrant flows” alongside capital flows, digital networks, and supply chains as evidence that “the world has invaded the nation,” weakened its borders, and transformed the existential conditions of populations.Footnote 102 Brown ties white men’s affirmation of supremacy and entitlement to the threat that neoliberalism poses to their status, and their racialized reaction to the fact that they hold “politicians … responsible for allowing [new immigrants] into the West.”Footnote 103 This framework superimposes “immigration as source of anxiety” over the complex role of mobility and migration in the founding of western democracies. From European migration populating settler colonies and easing excess labor problems in the metropoles to the Indian and Chinese indentured migration that facilitated continued labor control post-abolition and emancipation described in this chapter,Footnote 104 and the Mexican labor that made up for the eventual exclusion of Chinese and Indian labor, analyzed in the next chapter, migration appears as a world historical force that allows for the negotiation of shifting regimes of domination and capitalist accumulation on a world scale. Naturally, the salience of migration is intensified in moments of crisis, but the phenomenon itself is nested in and indicative of imperial labor control, which is missed when it is theorized simply as an external flow associated with globalization and neoliberalism. In this sense, migration control was and remains an essential governmental tool to racially filter foreigners and locate them on distinct paths in terms of access to land, political enfranchisement, and labor conditions vis-à-vis privileged whites. This racial filtering operates in tandem with historical declarations of the people that found and refound the settler polity. This explains its salience as a realm of governance when white status achieved through the historical marginalization, exclusion, and expropriation of nonwhite workers is in crisis. Without this background, the naming of the “backlash” against migrants prompted by neoliberalism simply begs the question of why this group is being targeted and problematically cast migrants as an external – rather than the group with and against whom white polities were founded. As this chapter shows, migration control functioned historically and still functions continuously with other racial capitalist arrangements domestically and globally, which are being reshaped by neoliberalism, rather than being outcomes brought about by this economic logic. In other words, this chapter’s proposed conceptualization of migration and its control transforms immigration from an external flow that prompts the authoritarian backlash into an imperial field whose evolution grounded and shaped the western polities that today reward anti-immigrant political agendas. This means that the xenophobic agendas that garner support at the time of writing are not an “inversion of values … [that closes] out three centuries of modern experiments with democracy,”Footnote 105 but a component part of how democratic regimes in the west took shape, and a core marker of the historically continuous racial exclusions of these polities.Footnote 106

Another displacement of the question of racial subjection generally and migration in particular is at work in Nancy Fraser’s comprehensive appraisal of capitalist crisis. Migrants appear in three instances in Fraser’s system: as the group of women of color who take up care work when state-managed capitalism is dismantled in the west; as part of the group of workers that are expropriated rather than exploited by capitalism historically; and – similarly to Brown – as the group that is targeted by white voters in their backlash against neoliberalism. To start with the third aspect, Fraser suggests that the fear of immigrants could be expressing the understandable anxiety “that things are out of control.”Footnote 107 This statement begs the question of why is it that the feeling “that things are out of control” does not result in solidarity with migrants, who, after all, come from countries where things have been “out of control” more regularly and for longer periods of time.Footnote 108 Fraser asserts further that disgruntled voters with real grievances react with racial hostility because they lack access to left-wing alternatives that can provide anticapitalist and anti-imperialist diagnoses of the crisis.Footnote 109 This problem, she adds, is compounded by the cooptation by neoliberalism of certain forces of emancipation, further reducing their appeal among industrial workers and rural communities.Footnote 110 What this account leaves out is that, as this chapter reconstructs, socialist and social democratic narratives were historically connected not only to capitalism, but also to imperial narratives of racial hierarchy and entitlement to rule, making contemporary reactions not a misunderstanding of emancipation, but the channeling of particular racialized threads of popular narratives that still hold currency and emotional appeal in Europe and the white settler world today.

In other words, the problem of the left is not just its cooptation by neoliberalism, but its equally worrying internalization of the racialized logics that characterize capitalism. Hillary Clinton’s advice to European leaders that they should get a handle on migration, because it “lit the flame” of right-wing populism, falls into this problem.Footnote 111 This line echoes a generation of left-wing politicians in Germany, France, and England, including Jeremy Corbyn, Mette Frederiksen, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, and Sahra Wagenknecht, who avoid, equivocate, or are skeptical about migration while embracing left-wing social policy.Footnote 112 This vision protects domestic white labor while evading addressing western global corporate practices that today, as in the past, benefit from the manageability of labor, including its global segregation and the vulnerability induced by tough migration policies. As in the past, too, this strategy deflects the transnational modes of imperial extraction operating now through neoliberalism that shelters western workers through the exclusion of migrants and mild wealth socialization. These measures are misguided even when judged by the goal of protecting the domestic working class, because privileging domestic struggles allows capitalist elites freer play worldwide, strengthening their power at home.Footnote 113 Most importantly, it displaces from left-wing agendas the politicization of business elites’ responsibility in global and domestic oppression, and the distinct but entangled conditions of workers around the world.

Thus, the contemporary reaction against migrant and refugee flows on the right and left, which perceive them, respectively, as unduly trespassing borders or as competing for social gains that rightfully belong to the native working class, needs to be understood in the context of the proposed genealogy of the imperial and popular roots of immigration control, that is, how white collectives aimed to appropriate territory and wealth while reaping the benefits of racial regimes of exploitation. The fact that the share of the wealth being distributed at the time of writing is increasingly paltry even in wealthy countries likely increases possessive anxieties among downwardly mobile white groups, who, like a century ago, tragically direct their anger to precarious nonwhite workers and migrants. This account also offers lessons for the US left, which does not explicitly oppose immigration but avoids contesting the right’s political economy framing of immigration as an economic threat. Here, the neoliberal cooptation of the left is operative because it prevents it from properly articulating and contesting capitalist labor control as implemented via the contemporary immigration regime of surveilled undocumented labor, thus leaving it to focus on humanitarianism and immigrant rights discursively, while departing only marginally from the right-wing focus on the militarized surveillance of borders and interior control in practice.Footnote 114

Fraser goes some way toward addressing this point in her account of capitalism by including immigrants in the group of workers subject to “expropriation,” that is, accumulation by other means that dispenses with contractual relations of wage labor to instead confiscate capacities and resources into capital’s self-expansion in violent ways or through veiled means of commerce and debt.Footnote 115 Here expropriated labor is facilitated by a political order that denies certain subjects the status of free citizens, whose subjection is a condition of possibility for the freedom of merely exploited workers. This chapter – and the book as a whole – goes further by showing both the complexities of the political order that facilitates the co-existence of diverse forms of subjection within expropriation, and the intimate connection between white democratic politics and the creation of these realms, which expropriation as a blanket term falls short of capturing. Rather than blanket expropriation, then, capitalism depends on a heterogeneous and dynamic field of action sustained by a popularly supported racial hierarchy that targets different racial groups with varied institutional tools and reacts to resistance and emancipation efforts by re-arranging these conditions in order to maintain workers’ docility.

To understand these entangled conditions, the first part of the book theorized the entanglements between racial capitalism, popular sovereignty, and empire. The second part, to which I now turn, attends to social reproduction and nature, realms that constitute two of Fraser’s hidden abodes, but whose emergence from the combination of racial capitalist priorities, technological developments, and “democratic” moments of enfranchisement in wealthy countries remains undertheorized. Social reproduction is also the realm in which Fraser addresses migration as a fix to the capitalist crisis of social reproduction. But the political aspects and historical pedigree of this fix remain undertheorized. It remains unsaid how longstanding democratic and family formations enacted and policed via collective rule entail ruling over racialized others whose labor and expropriated land provide the rulers’ conditions of possibility. In this vein, Chapter 3 theorizes the racial dynamics of social reproduction. In particular, it shows that diverse institutional formations such as conquest, guest work, and irregular migration, traditionally studied as separate phenomena, served, throughout history, the very same purpose of securing strenuous bodily work from Mexico at minimal cost. These formations both preceded and were intensified when the supply of Asian labor ended with the 1924 US immigration quota law and were/are facilitated by the unequal relation between the United States and Mexico. Chapter 4 extends this analysis to consider how the forced conscription of racialized labor occurs in tandem with the exploitation of nature, with both manual labor and nature being devalued through ideologies of techno-racism that disavow privileged subjects’ dependence on this couplet.