Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- 1 The Liao

- 2 The Hsi Hsia

- 3 The Chin dynasty

- 4 The rise of the Mongolian empire and Mongolian rule in north China

- 5 The reign of Khubilai khan

- 6 Mid-Yüan politics

- 7 Shun-ti and the end of Yüan rule in China

- 8 The Yüan government and society

- 9 Chinese society under Mongol rule, 1215–1368

- Bibliographical essays

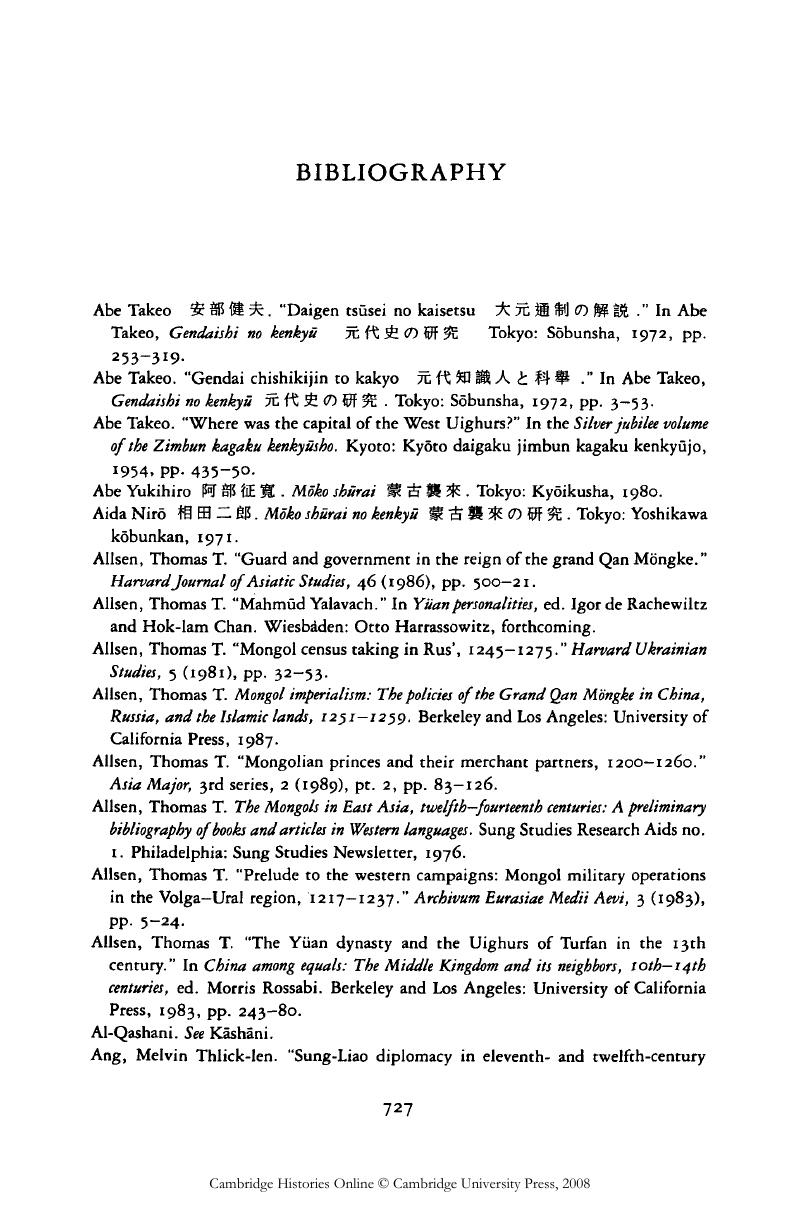

- Bibliography

- Glossary-Index

- MAP 7. The Liao empire, ca. 1045

- MAP 12. The Hsi Hsia state, IIII

- Map 17. The Chin empire

- MAP 32. The Yüan empire">

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 March 2008

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- 1 The Liao

- 2 The Hsi Hsia

- 3 The Chin dynasty

- 4 The rise of the Mongolian empire and Mongolian rule in north China

- 5 The reign of Khubilai khan

- 6 Mid-Yüan politics

- 7 Shun-ti and the end of Yüan rule in China

- 8 The Yüan government and society

- 9 Chinese society under Mongol rule, 1215–1368

- Bibliographical essays

- Bibliography

- Glossary-Index

- MAP 7. The Liao empire, ca. 1045

- MAP 12. The Hsi Hsia state, IIII

- Map 17. The Chin empire

- MAP 32. The Yüan empire">

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Cambridge History of China , pp. 727 - 776Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 1994