Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Old Women under Investigation: The Drab Housewife and the Grotesque Hag

- 2 Chimerical Procession: The Poetics of Inversion and Monstrosity

- 3 Priapic Ride: Gigantic Genitals, Penile Theft, and Other Phallic Fantasies

- 4 Magical Metamorphoses: Variations on the Myths of Circe and Medea

- 5 A Visit from the Devil: Horror and Liminality in Caravaggesque Paintings

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

3 - Priapic Ride: Gigantic Genitals, Penile Theft, and Other Phallic Fantasies

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 February 2024

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Old Women under Investigation: The Drab Housewife and the Grotesque Hag

- 2 Chimerical Procession: The Poetics of Inversion and Monstrosity

- 3 Priapic Ride: Gigantic Genitals, Penile Theft, and Other Phallic Fantasies

- 4 Magical Metamorphoses: Variations on the Myths of Circe and Medea

- 5 A Visit from the Devil: Horror and Liminality in Caravaggesque Paintings

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

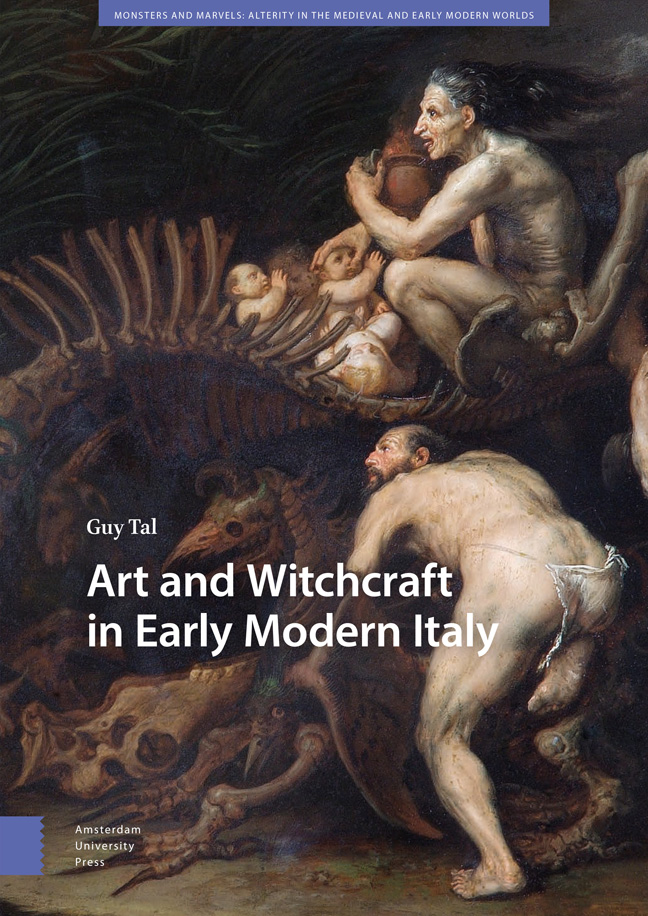

Abstract: Parmigianino's drawing of a witch riding a prodigious phallus, known today through two late print versions, has often been excluded from studies on early modern witchcraft and sexuality but is in fact indispensable to both. Its outward bawdiness belies a multilayered commentary on witchcraft lore and praxis. In each layer the phallus assumes a different function, oscillating between the literal and the figurative, the real and the fantastic. It relates, severally, to a man dominated by a witch, a castrated male organ, a demonic disguise, and a shielding amulet. Harboring sober ideas behind a superficially amusing facade, Witch Riding on a Phallus in effect canvasses a range of alternative reactions to the witchcraft phenomenon.

Keywords: humor, upside-down world, demonic illusion, delusion, Evil Eye, amulet

With characteristic verve, the Venetian satirist Nicolo Franco composed the following sonnet-shaped riddle, one of the delicious bawdy poems in his La Priapea of 1541: “It does not have feet but goes in and out. It is disarmed, but it has great courage. It does not have an edge, but is sufficient to cause blood. … It seems a great miracle because without ears it hears every noise, because it has no nose and yet likes to smell. It has no eyes, but it sees where to go.” Alas, the solution to the riddle is given at its very outset: “A great thing is the cock (cazzo), if we want to look at it.” This riddle, whereby the penis receives a life of its own—perhaps that of a warrior, in extension of the sex-as-warfare metaphor—is but one example among a plethora of genital humor, metaphors, and animation in Italian Renaissance learned erotica. Indeed, as Patricia Simons points out, in early modern Europe “male genitals give rise to logorrhea, to countless slang terms, verbal jokes and insults, to written and visual metaphors, double or multiple entendres, allusions, euphemisms and visual signifiers of power, puns, and play.” Her study shows the amplitude and variety of phallic symbols and double entendres in early modern art, from spades and lances to gourds and ladles. Less common at the time were artworks that reverse the path by which Franco's riddle is intended to be deciphered: instead of employing phallic motifs, these artworks flagrantly display virile members that invite the viewer to tease out manifold concepts and notions.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Art and Witchcraft in Early Modern Italy , pp. 131 - 188Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2023