Violence in the USSR during World War II assumed unthinkable proportions. In a witness statement composed in the newly liberated city of Kremenchuk, Ukrainian resident Dariia Mikhailovna Kiseleva described being unable to sleep due to “bloodcurdling screams” of Soviet prisoners of war confined in a Nazi camp near her home. She concluded, “In general, it is all difficult to recount and to describe, and even more difficult to believe, for someone who did not see it.”Footnote 1 Hundreds of kilometers to the west in L΄viv oblast, French prisoner of war Clément Loof testified to a similar feeling of inadequacy. “At night there was the murder of Jewish men and Jewish women,” he wrote. “It all happened in Rava-Russka, there were many other things that my friends saw that I did not see, it was horrible. You have to see it to believe it.”Footnote 2 Because most people would not be unlucky enough to see such crime scenes for themselves, Stalin's government marshalled images to convey the extent of Nazi brutality on occupied Soviet territory. Mixed in with these efforts was the quest to frame Hitler's forces for the NKVD's (Narodnyi komissariat vnutrennykh del) mass shootings of Polish prisoners of war in Katyn forest before the Germans arrived. The extent of Stalinist falsification of other atrocity investigations remains an open and contested question.

Kiseleva and Loof were two of a reported seven million people who contributed to the Extraordinary State Commission (Chrezvychainaia gosudarstvennaia komissiia, ChGK), the Soviet organization created on November 2, 1942, to gather evidence of atrocities and damage that took place during the Nazi occupation.Footnote 3 The novelty of the ChGK was evident from the outset, with Pravda, Izvestiia, Krasnaia zvezda, and the New York Times all publishing the founding decree in full.Footnote 4 By the following November, the ChGK had received a staggering 32,069 reports on violent crimes.Footnote 5 The United Nations War Crimes Commission, in contrast, established on October 20, 1943, without participation of the USSR, registered seventy cases from seventeen member countries during the same interval of operation, with half of the cases too incomplete to move forward.Footnote 6 The ChGK constituted a Soviet innovation in what had become an information war not simply against Hitler's Germany but among Allied and occupied countries. In April 1944, when preparing a report which alleged that the Nazi regime deliberately spread typhus, the ChGK's resident jurist, Il΄ia Pavlovich Trainin, warned participating epidemiologists to be on their guard: “Each inaccuracy can trigger evaluation not only from the Germans but even from countries friendly to us, our allies. Therefore, we want this document to be irreproachable.”Footnote 7 Where documents were not up to the task, images needed to fill in the blanks.

The Katyn falsification was a thread that ran through the entire fabric of the ChGK. In April-May 1940, the NKVD shot an estimated 22,000 Polish military officers and intellectuals, burying them in mass graves in Katyn forest as well as other locations. On April 13, 1943, less than one month after the ChGK began its work in earnest, Berlin radio announced the discovery of Polish victims near the NKVD dacha at Katyn and attributed the murders to Soviet state security organs. Subsequent broadcasts relayed the German launching of an investigation by experts from “neutral countries.” On April 15, 1943, Moscow radio accused Hitler's forces of massacring the Poles themselves, and in short order severed diplomatic relations with the Polish government-in-exile. More substantive distortions became possible once the Red Army's arrival in Smolensk oblast made way for Stalinist eyes on the ground. The ChGK investigation that followed in January 1944 would fuel the Soviet demand to include Katyn among the charges at the Trial of the Major War Criminals in Nuremberg in 1945–46, although the Allied court conspicuously avoided ruling one way or another on this count. Undeterred, the Soviet government cleaved to the ChGK's version of events at Katyn until Gorbachev broke ranks in 1990, around the same time that ChGK documentation first became available for research.Footnote 8

As work products ascribed to the Soviet state, ChGK records have been subject to significant suspicion. Marina Sorokina asserts that a “Katyn model” of the ChGK erasing Soviet crimes “was widely used by the Stalinists in other situations.”Footnote 9 Many historians have amplified Sorokina's hypotheses as conclusions, such as her conjecture that a central dictum for security organs to dominate local investigations was consistently realized in practice.Footnote 10 Certain other scholars condemn the ChGK for warping the historical record evidently without consulting the ChGK's archives first.Footnote 11 Such verdicts mirror broader controversies surrounding Soviet state documentation. A recent article took historians of World War II to task for relying on Stalin-era interrogation and trial records.Footnote 12 Related tensions appear in literature on photography in the USSR. While Holocaust scholars have elucidated Jewish photographers and specific images, the best-known critique of the Stalin period universalizes photographic manipulation while skipping over the war.Footnote 13 The latest publications foreground Soviet photography as an obfuscating medium by focusing on themes such as Gulag propaganda and security organ mug shots.Footnote 14

Perspective is everything. Among the cases Sorokina cites to support her claim of widespread falsification, all but one constitute material damage.Footnote 15 By design, ChGK documentation of economic destruction was malleable, as sums were supposed to encompass all war-related losses, including unrealized revenue, until peacetime conditions could be fully restored.Footnote 16 The sole instance Sorokina identifies of a ChGK investigation blaming Germans for Soviet violence was a frame-up in Kabardino-Balkaria, where local stakeholders misrepresented the NKVD's massacre of purported deserters and bandits evidently without Moscow officials ever being aware.Footnote 17 Other historians have taken aim at Maly Trostenets, a Nazi camp and mass extermination site outside Minsk. They suggest a top-down campaign that halted excavations and inflated death tolls to pass off Stalin's victims as the work of Hitler's regime.Footnote 18 Yet at this crime scene, some of the highest estimated death counts came from local residents who survived the camp.Footnote 19 Suspicious scholars credit the ChGK's chief forensic expert Nikolai Nilovich Burdenko with leading the cover-up because he advocated for immediately publishing the highest available victim count, but in doing so historians overrate his certitude. “In the future we are obligated to open and examine still more,” he told investigators in Minsk. “Once we receive the real numbers, we should take everything into account.”Footnote 20 Expedited publication of inchoate findings at Maly Trostenets hints at Burdenko's sincerity. Aside from Katyn, none of the known or suspected cases where Soviet propaganda attributed Stalinist murders to the Germans, such as Vinnytsia, Bykivnia, and Tatarka in Ukraine, were ever published in the ChGK's communiqués.Footnote 21

The “Katyn model” had the opposite effect from what scholars have presumed. Instead of poisoning the rest of the ChGK's work, the Katyn falsification led Stalin's government to crowdsource photographs and eyewitnesses of genuine German atrocities that could be likened to the mass shootings of Polish prisoners of war. This project was facilitated by overlap in the violent practices of Hitler's and Stalin's regimes. Through deployment of evidence from elsewhere in the occupied USSR, Soviet investigators obscured the Katyn exception: the sole case when a ChGK communiqué was dictated from above. Diverse participants in all stages of the ChGK's investigations became caught up in the Katyn lie, with western observers serving as human snapshots who disseminated their impressions abroad. In this way, lived experience fused with photographic documentation to reinforce intersections between personal truths and official narratives of Nazi atrocities in the Soviet Union.

Like other Stalinist schemes, the Katyn falsification took on a life of its own in ways that matter for researchers who use ChGK documentation. Here, it is crucial to remember that the mission of Soviet state organs was not to distort for the sake of it, but to further the political goals of the moment. For war crimes, this required imagery and testimony that could satisfy international as well as domestic audiences, material that individuals circulated for reasons of their own. Thus, the ChGK's collections should be evaluated as artifacts of mass mobilization which range from candid to malicious. Pursuing the grassroots origins of ChGK records offers a path forward that mitigates the potential disruption of inaccessible archives, such as central KGB holdings.Footnote 22 At the same time, moving beyond noncommittal speculation that falsification might be anywhere in the ChGK's work undermines the counterclaims that no fabrication took place, which are increasingly giving new strength to the old Katyn lie. Photographs are especially conducive to interpretation across transfers and manipulation because changes are visually recognizable. Katyn, a Nazi crime that never happened, was the hollow at the heart of the ChGK. By tracing its dimensions, this article deepens our understanding of the enduring power of Soviet documentation of mass atrocities: reverberations of extreme violence that are acquiring still more layers of meaning now that war has returned to the territory of the former USSR.

Picturing War

Hitler's regime was well aware of the persuasive value of images. In Krasnodar in September 1942, occupation authorities announced that a column of Russian prisoners of war would be passing through the city and local residents could give them water and food. Thousands of people reportedly gathered, but in the end automobiles full of wounded German soldiers arrived instead. Having arranged a scene in which it appeared that local residents were warmly greeting their injured overseers, Germans proceeded to photograph it.Footnote 23 Other forms of Nazi photography were more sinister. In Latvia, Germans and local members of the Arajs Kommando carried out mass shootings and then photographed the victims to give the impression of spontaneous pogroms against Jews and communists.Footnote 24 In some places, photography evidently served as a method for keeping track of the number of people murdered.Footnote 25

Representatives of the Nazi regime employed photography for unofficial purposes as well. In Rava-Russka, the ghetto commandant ordered that naked Jewish women be photographed in obscene poses before they were shot.Footnote 26 Soviet media attempted to exploit Nazi voyeurism, with the Red Army's newspaper Krasnaia zvezda publishing “candid” photos of executions seized from a German soldier. The accompanying caption read: “The photographs were in the German's wallet, and presumably he was happy to show them to his fellow looters and robbers.”Footnote 27 Nazi authorities had similar instincts, photographing excavations of victims reportedly shot by the “NKVD and Jews” for public distribution.Footnote 28 During a meeting in newly liberated Kyiv, the ChGK's jurist Trainin urged the auxiliary commission to fight back by documenting the mass killings at Babyn Yar. “We are thinking of responding to the Germans indirectly,” Trainin explained. “Here are German photographs of bodies with the accusation that the Bolsheviks did this. In fact, we will show along the way that this was their work.”Footnote 29

To accomplish this goal, Soviet cameramen traveled to newly liberated regions alongside ChGK representatives to photograph crime scenes and the investigation process.Footnote 30 The ChGK soon called for the creation of a “special division” under TASS, the Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union, to “systematize” photographs for use as “original documents characterizing crimes of the German-fascist troops.”Footnote 31 Some of this push to create a visual record of the occupation experience came from above. For example, when Trainin sent a request for permission to publish the ChGK's communiqué on Nazi crimes in Orel oblast to Andrei Ianuar΄evich Vyshinskii, the Deputy People's Commissar of Foreign Affairs responded that photographs must be included in the publication.Footnote 32 The Orel oblast commission and other auxiliaries disseminated this preference to local investigators by defining photographs as evidence equivalent to witness statements, without which no official report on Nazi crimes would be complete.Footnote 33 A pictorial record was especially important for documenting so-called “vivid crimes,” with photographers and medical workers responsible for playing the leading roles in such investigations.Footnote 34 When documenting the mass murder of Jews in what is today Luhansk, for instance, the Ukrainian republic commission deemed the absence of photographs and a conclusion from medical experts as equally serious problems that required immediate remediation.Footnote 35

Some investigators instinctively understood the need for visual evidence. In the Ukrainian SSR in April 1943, before the central ChGK began supervising investigations in earnest, the People's Commissar of Internal Affairs instructed local NKVD departments to assist oblast commissions by taking pictures of Nazi crime scenes.Footnote 36 In the city of Kaunas in Lithuania, NKVD operatives photographed corpses as they gathered them.Footnote 37 Other branches of the Soviet security apparatus joined in the project of creating a pictorial record of the occupation, for example, when Deputy People's Commissar of State Security Bogdan Zakharovich Kobulov supplied the ChGK with a photograph album depicting German atrocities in Kyiv.Footnote 38 Case files for the criminal prosecution of local residents who participated in Nazi crimes incorporated photographs of perpetrators as well as victims in happier prewar times, where they appeared like ghosts of the Soviet utopia that Hitler's regime was trying to destroy.Footnote 39

Historians frequently interpret the ChGK as a storefront for security organs.Footnote 40 This was not the way it seemed to the ChGK's investigators, with chief forensic expert Burdenko advocating for crowdsourced testimonies to determine the retaliative actions to be taken by the NKVD.Footnote 41 In Estonia, the procuracy administered the ChGK auxiliary, rather than security organs, and local residents volunteered pictures to support inquiries about loved ones.Footnote 42 Instructions on the central and local levels charged investigators with obtaining negatives from photographers among the general population, even as ChGK affiliates produced additional images of crime scenes.Footnote 43 In Kaunas, for instance, the NKGB (Narodnyi komissariat gosudarstvennoi bezopastnosti) sought out a Jewish photographer with pictures from the occupation years.Footnote 44 In L΄viv, the oblast commission published a newspaper announcement urging Soviet citizens to transfer their photographs to ChGK personnel.Footnote 45

Holocaust survivors had images that could not come from anyone else. When the ChGK's inspector and criminology expert in L΄viv learned that a Jewish prisoner forced to work as a photographer in the Janowska camp was still alive, the investigators rushed to his home immediately, even though it was two in the morning. Former prisoner Herman Lewinter provided these investigators with photographs he smuggled out of the camp when he escaped. In addition, Lewinter formally testified about his experiences and subsequently accompanied forensic experts to photograph excavations of mass graves.Footnote 46 Surviving Jews played similarly prominent roles in generating a visual history of atrocities in Latvia. Here, two Jews who formally worked for the ChGK auxiliary compiled an album of photographs of Nazi crimes, certifying images and composing captions.Footnote 47 Another Jewish survivor forced by the Germans to clean and sort clothing from west European Jews shot in Riga secretly preserved photographs he discovered as he worked, which he later volunteered to the Latvian republic commission.Footnote 48

In sum, the ChGK's visual record of the Nazi occupation assumed many different forms. Forensic excavations were a major focus. At Maly Trostenets, as ChGK investigators examined thirty-four pits in July 1944, they generated four maps and sixty-five photographs.Footnote 49 Photography provided a sense of place, conveying the contours of crime scenes for audiences fortunate enough never to visit these locations in person.Footnote 50 Photographs became formal records of the identities of victims, as survivors of mass violence were called upon to “confirm” the names attached to images of corpses.Footnote 51 Photography captured survivors as well. For example, the newspaper Krasnoe znamia published a photograph of a ten-year-old Jewish girl from Globino village in Poltava oblast along with the story of how the rest of her family was shot because the father was Jewish.Footnote 52 Perpetrators were additional focal points. In Labinskaia stanitsa in Krasnodar krai, when a ChGK member interrogated a Soviet woman who married the head of the Gestapo, she asked her to name him and other people in a recovered photograph.Footnote 53 Soviet investigators were particularly intent upon having Jewish former camp prisoners identify war criminals. In L΄viv oblast, surviving Jews accompanied investigators to search apartments for photographs of German officers.Footnote 54 Local residents were then left with the unpleasant task of explaining not only the identities of the Nazi leaders, but how they had come to possess such suspicious photographs.Footnote 55

Soviet Storytelling about Katyn

The challenges of explaining incriminating courses of events while deflecting blame were ones that Stalin's government knew well. At the time of the German invasion, the USSR was still reeling from mass repressions in 1937–38 that touched every sector of society and left the country on poor footing to meet the demands of total war. In 1939–40, tens of thousands of people petitioned their convictions or the sentences of loved ones, and while many verdicts were overturned, this could not bring back the dead or make mass graves of shooting victims disappear.Footnote 56 Soviet leaders worked hard to spin news of internal crises, but observers who wanted to know did not lack evidence.Footnote 57 Born on December 7, 1917, Kathleen Harriman was nearly the same age as the first socialist state. By her own admission, as the daughter of the US ambassador to the USSR, Harriman lived a largely sanitized existence behind “four big high walls” in Moscow, so when she made it out, she paid attention. For example, in a letter sent to a friend in London she took care to note that the ambassador's dacha “was built for an NKVD bigwig who subsequently lost his neck.”Footnote 58 As Harriman and the rest of the world would discover, it was the site of another NKVD dacha that posed the major threat to the Soviet public image.

On September 22, 1943, three days before liberation of the city of Smolensk, the director of the Communist Party's Department of Agitation and Propaganda, Georgii Fedorovich Aleksandrov, wrote to the leader of the Soviet Information Bureau, Aleksandr Sergeevich Shcherbakov. Aleksandrov recommended that a dedicated commission composed of representatives from the ChGK and security organs arrive in Katyn forest alongside frontline troops.Footnote 59 Trainin and Burdenko were already thinking along those lines when they reported up the chain of command their view that the corpses in Nazi propaganda about Katyn corresponded with victims of German mass shootings elsewhere in the USSR “like two geometric figures.”Footnote 60

The question was how to make the rest of the world see the same pattern. On January 12, 1944, the ChGK established a “special commission” chaired by Burdenko for investigating the murders of Polish prisoners of war in Katyn forest “by the German-fascist invaders.”Footnote 61 Burdenko assembled a team of fellow forensic specialists who had experience at the ChGK's other crime scenes.Footnote 62 Yet there were signals from the outset that investigators were dealing with a novel situation. Judging from the records of the ChGK's secretariat, members received a postdated draft of the communiqué authored by the “special commission” at the same meeting when it was formed.Footnote 63 Furthermore, out of thirty communiqués that the ChGK released in 1943–47, the Katyn report is the only one that does not have a working file containing drafts, correspondence, and source material assembled in the course of development. The ChGK's own workflow required crowdsourcing information. When documenting supposed Nazi crimes in Katyn forest, the driving force behind the investigation came from above.

To ensure that everyone involved shared the same vision, Deputy People's Commissar of Internal Affairs Sergei Nikiforovich Kruglov attended the first meeting of the “special commission” to explain the “special thoroughness and exactness” that were necessary for the Katyn investigation. NKVD operational workers had already reclaimed their dacha in the forest and spent three months collecting nearly 100 purported witness statements, but Kruglov clearly viewed these testimonies on their own to be inadequate. Burdenko recounted to the “special commission” the striking similarities he perceived between the murders at Katyn and the photographs of German executions published in Krasnaia zvezda that were discussed above. Burdenko emphasized the importance of photographing the entire excavation process at Katyn.Footnote 64

Establishing a visual record of German guilt at Katyn turned out to be more complicated than expected. During an on-site meeting on January 19, 1944, Viktor Il΄ich Prozorovskii, leader of the State Scientific-Research Institute of Forensic Medicine, warned that the quantity of excavation photographs was “insufficient,” while the quality “has not yet been verified.”Footnote 65 Prozorovskii was evidently not alone in his concern. The Katyn communiqué published in the Soviet press one week later and in English soon after did not include any images, and an album compiled for the investigation consists almost entirely of pictures of individual skulls against a black backdrop.Footnote 66 (Figure 1.) The writer Aleksei Nikolaevich Tolstoi, a member of both the ChGK and the “special commission,” advised against releasing film footage. “In its present form it is not only completely unsuitable for showing, but it could even have a negative effect,” Tolstoi informed Nikolai Mikhailovich Shvernik, the ChGK's chairman. “The scene with the questioning of witnesses makes it seem like the witnesses are repeating some kind of memorized lesson. Their speech comes off lifeless and therefore implausible.”Footnote 67

Figure 1. The first page of the album assembled by the Katyn “special commission,” c. January 16–23, 1944. GARF, f. R-7021, op. 114, d. 14, l. 1.

The falsified investigation of Katyn marked a turning point for the ChGK's reliance on visual documentation nevertheless. In March 1944, Burdenko, Tolstoi, and other participants in the Katyn “special commission” formed a new “editorial commission” to publish evidentiary materials. This publication project entailed the heads of the All-Union NKVD and NKGB ordering local security organs to collect photographs “characterizing the German method of shooting.”Footnote 68 The “editorial commission” prepared a volume titled “What is the Ideology of Hitler and the German-Fascist Command on the Destruction of Peoples in a Historical Perspective” that featured the Katyn massacre as the case study, supported by photographs seized from German soldiers, such as the images of gunshot executions previously published in Krasnaia zvezda.Footnote 69

The need to create pictorial context for the Soviet version of events at Katyn influenced future investigations of mass graves. In 1944, the central ChGK issued updated instructions for investigators that featured examples of documentation exclusively from Katyn and Smolensk, while warning that corpses must be photographed at the pit from which they were removed and not “in isolation,” so as not to give the impression of “staging.”Footnote 70 Auxiliary commissions distributed iterations of these instructions locally.Footnote 71 Such specific directions represented something new for the ChGK. Back in early 1943, two months before ChGK members met for the first time, the Soviet procuracy sent chairman Shvernik draft instructions for investigating Nazi atrocities that recommended “capturing [fiksatsiia] crimes with the help of photography.”Footnote 72 Similarly, draft instructions directed at military medical personnel advised photographing crime scenes “at the slightest opportunity.”Footnote 73 Yet such counsel was left to languish in a ChGK working file. The instructions for documenting violent crimes that the ChGK confirmed on May 31, 1943, mentioned photographs only once in passing, in the middle of a long list of different types of evidence that potentially could be appended to official reports.Footnote 74 It was only after the Katyn mass graves became a crisis for Stalin's government that photography of crime scenes was worthy of special attention. On a comparable timeline, a circular letter addressed to frontline film crews proclaimed: “Shoot the atrocities and destruction of the Germans, the most terrible, the most severe, adapting to aesthetic requirements.” Composed on December 2, 1943, this directive was distributed only months later in 1944.Footnote 75

In examining the ChGK's wartime publications as a whole, the role of Katyn as a turning point for photographic evidence becomes clear. Out of eight communiqués published before the Katyn report, only two—or 25 percent—included photographs.Footnote 76 In contrast, of the seventeen communiqués published between the Katyn report and the end of the war, thirteen—that is, 75 percent—featured pictures.Footnote 77 The lessons of Katyn were lasting. When submitting documentation to the Soviet team at Nuremberg, the ChGK sent photographs even for places like Stavropol΄ krai and Kyiv oblast, for which the published communiqués had not included images.Footnote 78 Beyond Nuremberg, the ChGK supplied photographs and other documentation of German atrocities for postwar trials in Krasnodar, Kharkiv, Smolensk, Mykolaiv, Briansk, Leningrad, Minsk, Kyiv, Velikie Luki, and Riga.Footnote 79 Such wide distribution ensured that everyone in the USSR, and whoever wanted to know abroad, clearly understood what Nazi crimes looked like. All such crimes looked the same as the mass shootings of Polish prisoners of war at Katyn.

To be sure, the consequences of the Soviet falsification of the Katyn massacre did not operate in a vacuum. Other factors over the course of 1944, such as the Red Army crossing into foreign territory and the increasing confidence in a Soviet victory, coalesced with the Katyn crisis to bring about a turn to visual storytelling. Nor could photographs of genuine or fabricated Nazi atrocities function independently. Stalinist decision makers understood the latter point even at the time, and to that end took a page from the German playbook by inviting international observers to witness the Soviet rendition of the Katyn crime scene. The US ambassador's daughter often lamented her cloistered lifestyle when corresponding with loved ones. In her first trip outside Moscow, Harriman would encounter the best of the worst of what Soviet power had to offer.

Falsification through Contextualization

Images of mass violence are a powerful force. Without them, all Soviet allegations of Nazi crimes could seem implausible. Foreign journalist W. H. Lawrence, for example, openly doubted the German massacre of Jews at Babyn Yar after attending the ChGK's presentation of the site in November 1943, in large part due to the Nazi policy of burning corpses. “There is little evidence in the ravine to prove or disprove the story,” Lawrence reported in the New York Times. “On the basis of what we saw, it is impossible for this correspondent to judge the truth or falsity of the story told to us.”Footnote 80 Katyn was a different story. Here, Soviet investigators left little to the imagination when leading western observers on a tour of the crime scene in January 1944, displaying mass graves still filled with corpses and autopsying victims as the visitors watched.Footnote 81

Harriman's presence transformed the Katyn pilgrimage into a diplomatic event. Once the ambassador proposed that she join, Soviet officials pivoted from a journey by truck that would require the westerners to bring their own food and drink for three days to supplying a well-provisioned sleeper train for what remained a challenging 36-hour roundtrip from Moscow.Footnote 82 The ordeal was worthwhile, according to the report Harriman submitted to the US Secretary of State. “It is my opinion that the Poles were murdered by the Germans,” she declared. “The most convincing evidence to uphold this was the methodical manner in which the job was done.”Footnote 83 (Figure 2.) Harriman expressed similar conclusions in her private correspondence, relaying to a friend: “While I was watching, they found one letter dated the summer of ’41, which is damned good evidence.”Footnote 84 Nor was Harriman alone in believing what she saw. For Lawrence, the proof for Nazi culpability rested in the fact that victims were buried fully dressed. “Never before in all my travels in the Soviet Union had I seen corpses wearing shoes, to say nothing of good boots or fur coats,” he wrote in his memoir published in 1972. “These items were in such short supply for the living they were never buried with the dead. On this basis, I decided that it was the Germans, not the Russians, who had murdered the Polish officers at Katyn.”Footnote 85

Figure 2. The final page of the Katyn “special commission” album. The sole woman pictured is Harriman. GARF, f. R-7021, op. 114, d. 14, l. 24.

Majdanek, the Nazi extermination camp in Lublin, Poland, served as further visual confirmation. “Whatever doubts about Russian versus German guilt might have lingered after the trip to Katyn were to be removed entirely after my visit in late August, 1944,” Lawrence remembered. “I can still see those bodies lying on stone slabs waiting to have their teeth examined for the gold they might contain, and I can still remember those piles of shoes, of clothing, and other possessions ready for shipment back to Germany.”Footnote 86 The ChGK worked to reinforce such connections between Katyn and Majdanek, zeroing in on survivor testimony and investigators’ own observations that German efforts to destroy corpses at Majdanek were a direct consequence of the Soviet “exposure” of Nazi crimes at Katyn.Footnote 87 By that point, Soviet persuasiveness was the product of momentum, with western observers such as Lawrence operating as human snapshots capable of conveying the horrors they had seen. The ambassador advised Harriman against visiting Majdanek, likely due to escalating tensions between the USSR and the Polish government-in-exile.Footnote 88 But Lawrence made the Soviet case by proxy. In a letter to her sister, Harriman described Lawrence as “the biggest skeptic among correspondents here on any horror story he sees,” now someone who discussed Majdanek “with tears in his eyes.”Footnote 89

The retaking of L΄viv oblast on July 28, 1944, was another important step in the Soviet quest to contextualize the Katyn massacre. Here, in response to earlier Nazi propaganda that blamed Jews for the NKVD's shootings in L΄viv, ChGK investigators asserted that Germans used Katyn to justify past and future Nazi atrocities, and to foment “a wave of hatred against Jews” among the Polish population.Footnote 90 Witness testimony asserted that Poles found German propaganda on Katyn too heavy-handed to be convincing.Footnote 91 The ChGK's communiqué published in late 1944 doubled down on the relationship between mass murder in Katyn forest and genuine Nazi atrocities in L΄viv, proclaiming their “complete identicalness.”Footnote 92 (Figure 3). Evidence suggests that some investigators took these purported links to heart. In a “completely secret” report evaluating potential witnesses for the Nuremberg trial composed on November 22, 1945, leaders of the NKVD, NKGB, and the procuracy in L΄viv oblast specified for their republic-level counterparts in the Ukrainian capital that a Jewish survivor of the Janowska camp had been forced to exhume and burn corpses of Nazi victims only “after the Katyn provocation.”Footnote 93

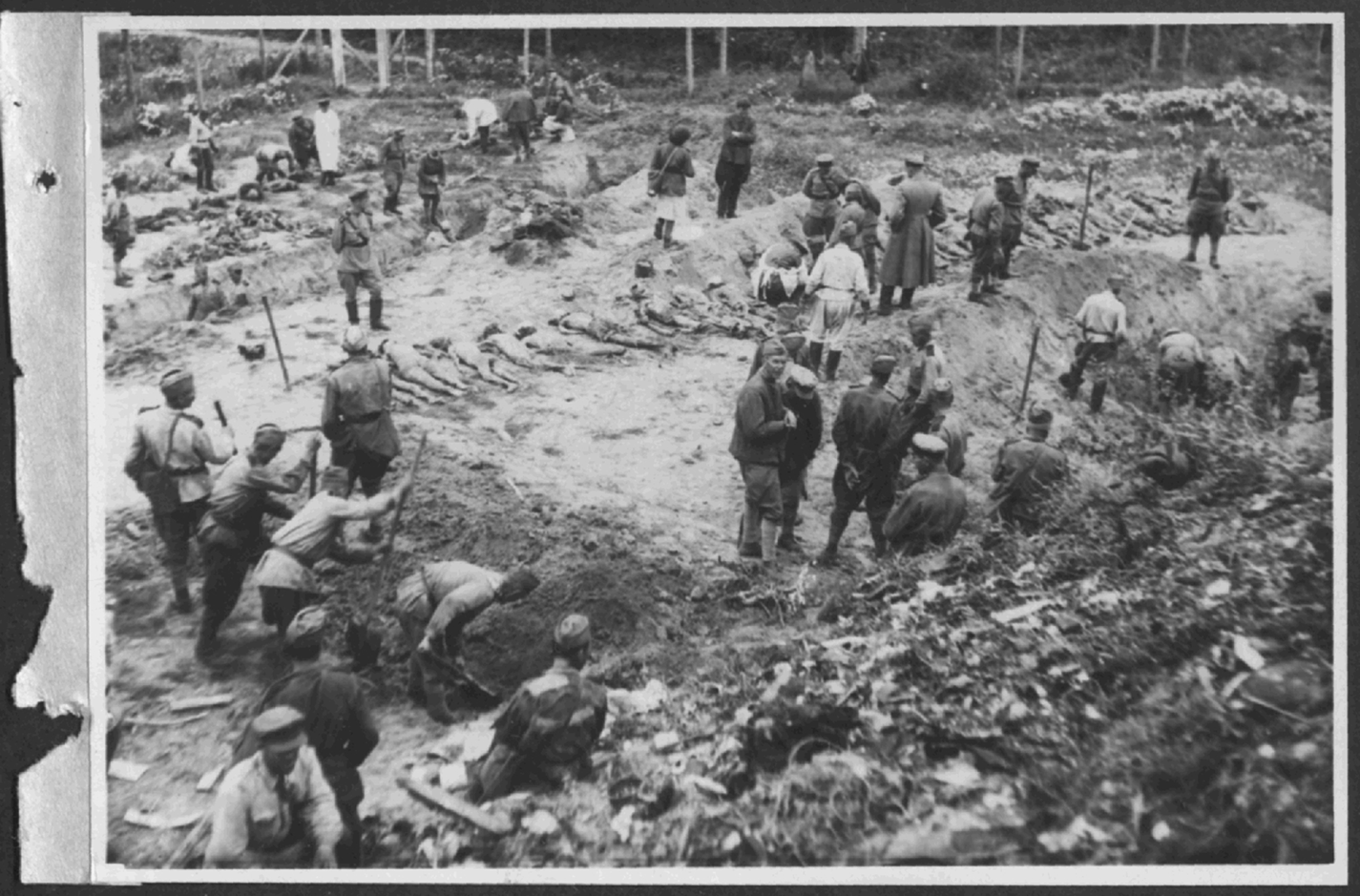

Figure 3. Excavations of victims from Janowska camp, c. September 9-October 20, 1944. Photograph taken by Soviet criminology expert Nikolai Ivanovich Gerasimov. GARF, f. R-7021, op. 116, d. 83, l. 138.

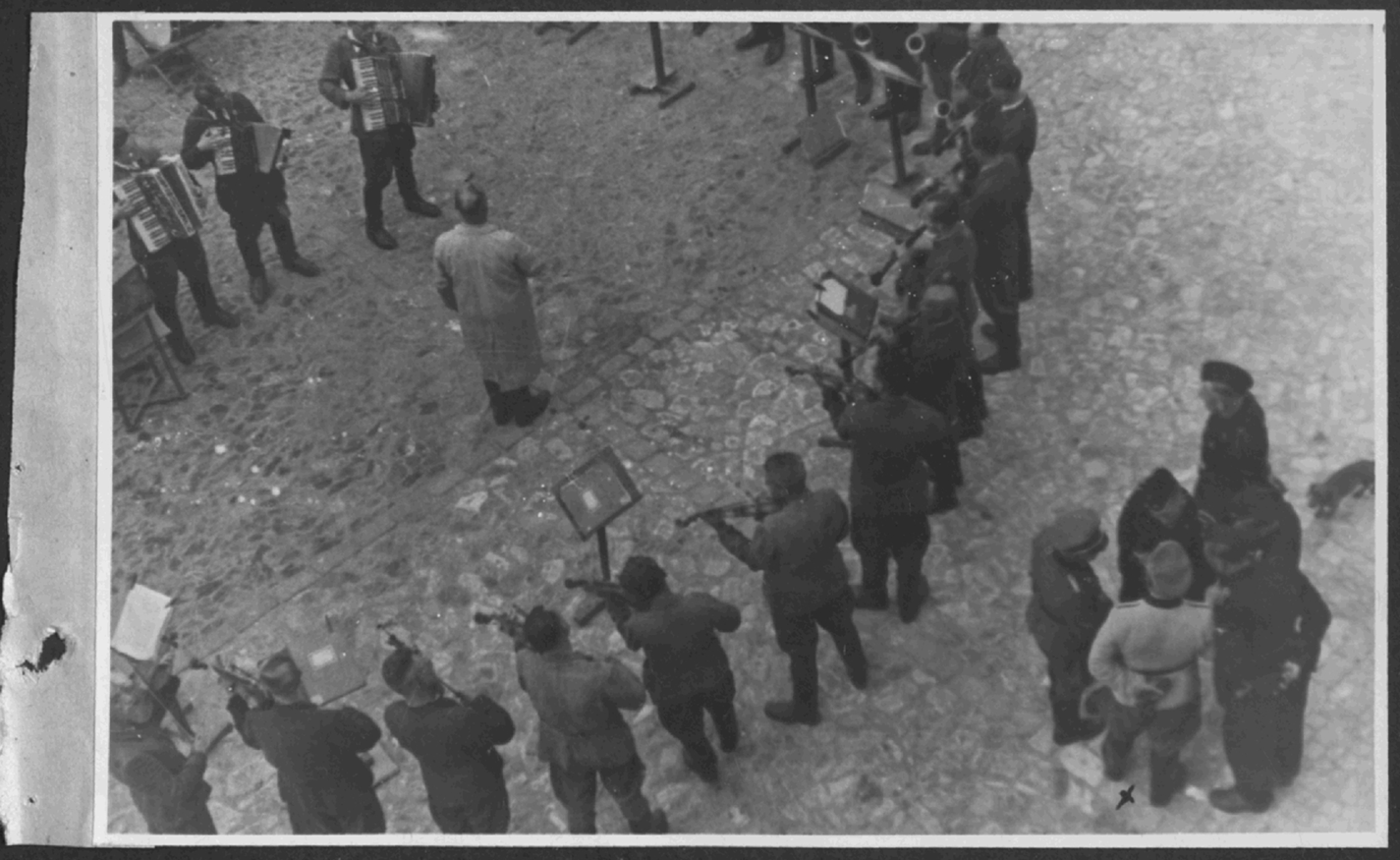

Photographic evidence underscored such stories and kept them from remaining abstract. Another Jewish survivor forced to burn corpses at Janowska worked with Soviet investigators to collect photographs left behind by murdered prisoners.Footnote 94 Investigators were especially interested in a photograph of the camp orchestra that they received from Herman Lewinter. (Figure 4). The central ChGK's inspector recalled decades later in his memoir that before seeing this image he was not certain the orchestra really existed. It took a picture to convince him to believe the accounts of prisoners compelled to play a song called the “Tango of Death” when no survivor could remember the melody.Footnote 95 The leader of the ChGK's investigatory group in L΄viv determined that a Jewish prisoner took this photograph in secret. When German overseers discovered the image, they made an example of the man by hanging him and throwing knives at his strung-up body.Footnote 96 The ChGK's published communiqué on L΄viv oblast featured this picture prominently alongside photographs of victims being transported to their deaths, a mass grave full of corpses, and other images.Footnote 97 (Figure 5). The Soviet prosecution showed the orchestra photograph at Nuremberg, and post-Soviet museums in Ukraine have largely continued its use as the quintessential image of the Holocaust in L΄viv.Footnote 98 But somewhere along the way the provenance got lost. The verso of the copy in the working file for the ChGK's communiqué identifies this image as a German photograph, an erroneous designation that the Soviet press reproduced.Footnote 99 A collection of Lewinter's photographs at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), which includes this image, mistakenly gives the impression that he took all the pictures himself.Footnote 100 Copies of these same photographs in the KGB archives in Kyiv that were assembled for an investigation of Janowska camp in the 1970s do not credit Lewinter at all.Footnote 101

Figure 4. Photograph obtained from Herman Lewinter and published in the ChGK's communiqué on Lviv oblast, December 23, 1944. GARF, f. R-7021, op. 116, d. 83, l. 144.

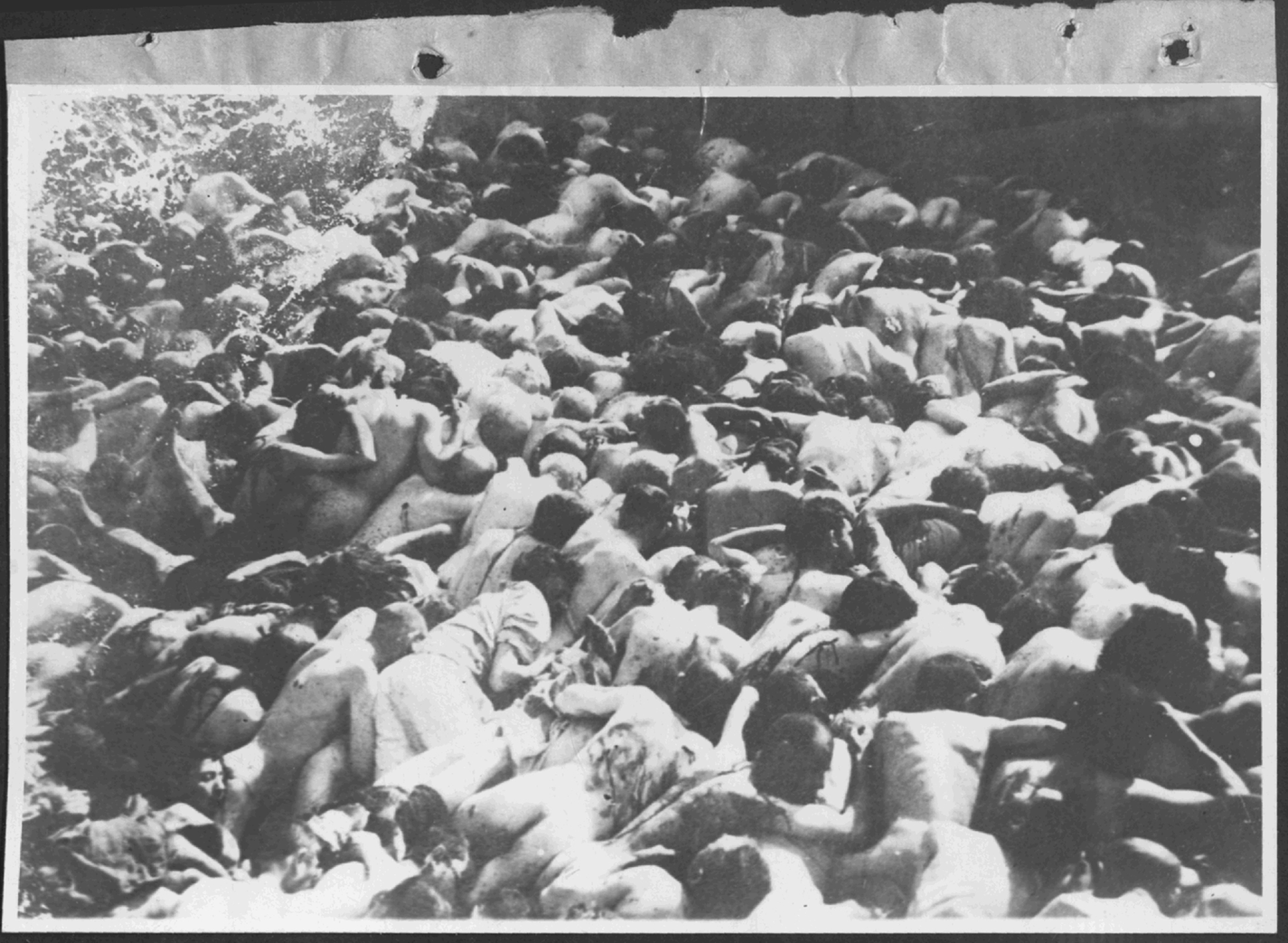

Figure 5. Photograph of victims from Zolochiv that appeared adjacent to the orchestra picture in the ChGK's communiqué, December 23, 1944. GARF, f. R-7021, op. 116, d. 83, l. 145.

Pictures like the image of Janowska's orchestra capture more than German cruelty and victims’ suffering. Such photographs incarnate the mass mobilization that made Soviet wartime investigations possible. Scholars can analyze the orchestra photograph today only thanks to a Jew who dared to take it, another who was brave enough to smuggle it out of the camp, a party activist who alerted the ChGK to the second man's existence, and the ChGK investigators who made sure to follow up.Footnote 102 This workflow was not according to plan. Stalin's regime created the ChGK to establish a “complete record of the vicious crimes of the Germans and their accomplices.” In pursuit of this goal, the ChGK was empowered to give assignments to investigative organs as well as to dispatch representatives across Soviet territory who were answerable only to the ChGK.Footnote 103 In turn, Stalin's government approached photography as inherently political work. ChGK photographers were subject to review by security organs.Footnote 104 Those who won approval traveled with certificates formally authorizing them to assemble pictures with the right to expect cooperation from all party, state, and military organizations.Footnote 105 The ChGK evolved into a photographic authority, with everyone from the Soviet Information Bureau to the NKGB requesting that the ChGK “certify” their photographs.Footnote 106 But in practice it was the contributions of ordinary people and the ubiquity of images of wartime atrocities that became convincing. Even when photographs were lacking, human snapshots, Soviet and western, spread word of what they had seen. Everybody had observed something for themselves that led them to believe everything else, including Soviet false explanations for Katyn.

Visual Trails

The Soviet falsification of the Katyn massacre reverberated in unexpected ways. British journalist Alexander Werth arrived in the city of Orel on August 10, 1943, soon enough after liberation that his visit overlapped with the ChGK's Burdenko. Werth watched Soviet officials sorting skulls according to the presence of bullet wounds and interviewed a local doctor who was a major witness for the ChGK.Footnote 107 Drawing on these experiences, Werth published a series of articles in the New York Times that shared his impressions.Footnote 108 In one publication, Werth relayed the horror that overcame Anglo-American correspondents who observed the ChGK's investigatory work. “I had seen such things in photographs but never in real life,” he wrote. “Beside a dug up trench were laid out strange, shriveled shapes of what had once been men. They looked like grotesque brown rag dolls.” In Werth's view, parallels with Katyn were self-evident: “I couldn't help remembering the gruesome details the Germans had produced about ‘piles of corpses of Polish officers murdered by the Russians.’ Their descriptions were reminiscent of what we were seeing now, and both bore the hallmark of the Gestapo.”Footnote 109

Werth's perspective changed based on time and place. When introducing his famous tome Russia at War, 1941–1945, released in 1964, he declared upfront, “I tend to agree with the Russian version of Warsaw, but not at all with the Russian version of Katyn—at least pending further information, which is remarkably slow in appearing.” Werth's reminiscences of his visit to Katyn alongside Harriman and Lawrence are more equivocal. In his retelling, while the outing had a “distinctly prefabricated appearance,” the circumstantial evidence “on the face of it, was favourable” to Soviet claims of German guilt at Katyn.Footnote 110 Readers on both sides of the Iron Curtain latched on to Werth's ambiguity. In 1967, his account became the subject of a debate in the New York Times’ letters to the editor that reached its polemical peak when Robert Conquest branded Werth “quite valueless in this context.”Footnote 111 Meanwhile, an abridged Russian translation of Werth's book published in Moscow that same year retained discussion of his visit to Katyn, with the Soviet editor framing Werth's study as an “exception” to generally hostile “bourgeois historical literature.”Footnote 112 Even looking back in 1995, on the other side of the Soviet collapse, Stalin's former bodyguard Aleksei Trofimovich Rybin pointed to Werth's text as supporting the view that “the shooting of Polish officers was carried out by German SS troops.”Footnote 113

For western audiences, the Katyn falsification was a contagion that seemed to spread without limits. During the McCarthy era, people as privileged as Harriman, former US Chief Prosecutor at Nuremberg Robert H. Jackson, and the late President Roosevelt came under fire for their credulity.Footnote 114 Lawrence went on record in Harriman's defense: “The evidence was inconclusive either way,” he emphasized. “We were impressed that most of the men still had on excellent boots. That the Russians, who desperately needed shoes, would bury 11,000 pairs of good boots seemed hard to believe.”Footnote 115 By the time Harriman was summoned before a House Select Committee to explain herself, she had been confronted with an interim report that not only “conclusively and irrevocably” attributed guilt to Stalin's government, but presented Katyn as a potential “blueprint” for the Soviet treatment of 8,000 US soldiers captured while fighting in Korea.Footnote 116 Faced with such opposition, Harriman was at a loss. “You had access to every side of the picture, which I did not have available to me,” she conceded under questioning. “I would say, having read your report, that my opinion is that the Russians did kill the Poles.”Footnote 117

In the years since, other people who sought to speak out on war crimes in the USSR have received similar pushback. Frida Zelikovna Michelson was one of three Jews who survived mass shootings in the Rumbula forest near Riga in 1941.Footnote 118 Even as she provided valuable eyewitness testimony for the ChGK, she endured scrutiny from security organs suspicious of how she escaped with her life. Michelson emigrated to Israel in 1971, but if she thought the days of state officials distrusting her were over, she was wrong.Footnote 119 In 1979, at the age of 72, she journeyed from Haifa to Baltimore to testify against a Latvian permanent resident of the United States accused of participating in the Rumbula massacre.Footnote 120 “He is imprinted on my memory, photographed in my memory,” she told the court of the defendant. “I exclude the possibility of any error.” Nevertheless, the judge ruled that Michelson was unable to make a “positive identification of the Respondent.”Footnote 121 Actual photographs of Latvian perpetrators did not fare much better, with West German prosecutors using Soviet images for identification purposes in court even as they denigrated the publications that contained them as “propaganda brochures.”Footnote 122 Holocaust deniers cite Katyn as reason enough for discarding all ChGK evidence out of hand.Footnote 123

The history of the Katyn falsification and Soviet war crimes investigations more broadly has been one of unforeseen consequences. The most significant photographs for understanding the truth behind the massacre of Polish prisoners of war in Katyn forest did not come from the ChGK or the USSR. Rather, examination of Luftwaffe wartime aerial photoreconnaissance beginning in 1981 enabled analysts from the CIA, elsewhere in the US, and Poland to determine that the mass graves at Katyn predated the Nazi occupation, a revelation that helped prod Gorbachev into acknowledging Soviet responsibility in 1990.Footnote 124 Thus, Hitler's regime had the necessary exculpatory evidence when it mattered but proved unable to exploit it. Awareness already in mid-1943 that the German death toll dwarfed the Katyn massacre may have been a factor.Footnote 125 An Annals of Communism volume released in 2007 devotes a separate section to these aerial photographs while also reproducing images from the Nazi-led excavations at Katyn. No pictures from the Soviet investigation appear.Footnote 126 From this perspective, it is clear that efforts to launder the NKVD's crimes under the auspices of the ChGK were a failure.

People caught up in Stalin's gamble lost a great deal. When Burdenko died on November 11, 1946, the many accomplishments of his life included operating on wounded soldiers in two world wars and founding what is known today as the Burdenko Neurosurgery Institute in Moscow, but the New York Times chose to focus on the most ignominious. “Gen. Burdenko, 68, Surgeon, Is Dead,” the title of his obituary read. “Headed Special Soviet Group that Probed Katyn Forest Massacre of Poles.”Footnote 127 Two decades later, Werth received similar treatment. Before discussing Werth's body of work, his obituary specified that, “Though never a Communist, Mr. Werth was generally sympathetic to the Soviet Union.”Footnote 128 Born one month after the Bolshevik Revolution, Harriman outlived the USSR by almost twenty years. Her obituaries routinely mentioned her implication in the Katyn falsification, even the one authored by her son.Footnote 129

Scholars have generally treated Harriman harshly, portraying her as at best naïve. For example, a major study of the Katyn aerial photographs misrepresents her as the lone US observer who accepted the Soviet narrative and, based on her noncommittal response when contacted by a researcher in the 1990s, ventures that, “Harriman still seemed to accept the Russian version.”Footnote 130 Her wartime correspondence reveals a more independent thinker than such judgments allow. In her own words, Harriman emerges as someone capable of condemning the “phoney air” of church services in Moscow who was at the same time haunted by the suffering she encountered. “Can you imagine watching the slow starvation of each member of your family,” she wrote to a friend in London. Just as Harriman's proximity to the Soviet experience helped her envision this torment better than her correspondent, unscripted moments during her visit to Katyn reinforced official narratives. Describing what she saw after sneaking out of a speech in Smolensk, Harriman marveled most at the way a “peasant woman” recounted mass murder “just as though she were discussing the weather. These people certainly are tough.”Footnote 131

In certain respects, the Soviet falsification of the Katyn massacre is paying dividends still. The Stalinist effort to substantiate the ChGK's explanation for Katyn produced a rich photographic record. Like the rest of ChGK documentation, photographs are not homogenous work products mirroring the will of a totalitarian state, but artifacts of mass mobilization, with much of the participation sincere. The power of these images lies in their reflecting a reality that was easily recognizable for people who witnessed atrocities. Soviet stakeholders could then liken mass graves at Katyn to German handiwork because there were so many examples of Nazi violence to choose from. The marshalling of visual evidence would become a campaign without end. On May 9, 1945, even as German military leaders signed a reworded document of capitulation at the demand of Stalin's regime, ChGK investigators delivered a picture of a corpse at Maly Trostenets for publication in the Soviet press.Footnote 132 Today, hundreds of similar images are available on a website launched in 2020 by the Federal Archival Agency of the Russian Federation, with a domain name that invokes the outrage of victimhood (victims.rusarchives.ru). Photographs of Katyn do not appear; they are not required. Instead, there are images from other investigations in Smolensk oblast, along with an account from Il΄ia Erenburg at Nuremberg that lists German attempts to blame the USSR for Katyn as only one of many disgraces at the trial, which included antisemitic rhetoric and insult to a survivor of Auschwitz. As he warned Soviet readers at the time, the struggle for truth about war crimes in Europe was just getting started.Footnote 133

Increasingly in recent years, responsibility for mass murder at Katyn has again become the subject of debate. On June 22, 2023, the 82nd anniversary of the Nazi invasion of the USSR, Russian media announced the declassification of testimonies from German prisoners of war which supposedly establish that after all, Katyn was the work of Hitler's regime. A captured photographer is quoted as recounting in 1947 how he and his wartime colleagues manipulated pictures and foreign observers to misrepresent Nazi crimes at Katyn and elsewhere as the responsibility of Soviet forces. The contemporary parallels are heavy-handed. RIA Novosti concludes that the post-Soviet Ukrainian government employed similar tactics when broadcasting photographs of atrocities in Bucha in spring 2022.Footnote 134 It may be tempting to dismiss such narratives and Russian citizens who embrace them as not worthy of engagement, much like Holocaust scholars refuse to argue with people who deny the genocide took place. There are important differences here, however. The Katyn falsification succeeded in the past not through downplaying the massacre, but by enabling people who witnessed the consequences of the German occupation firsthand to integrate the Soviet version of Katyn into their own experiences.

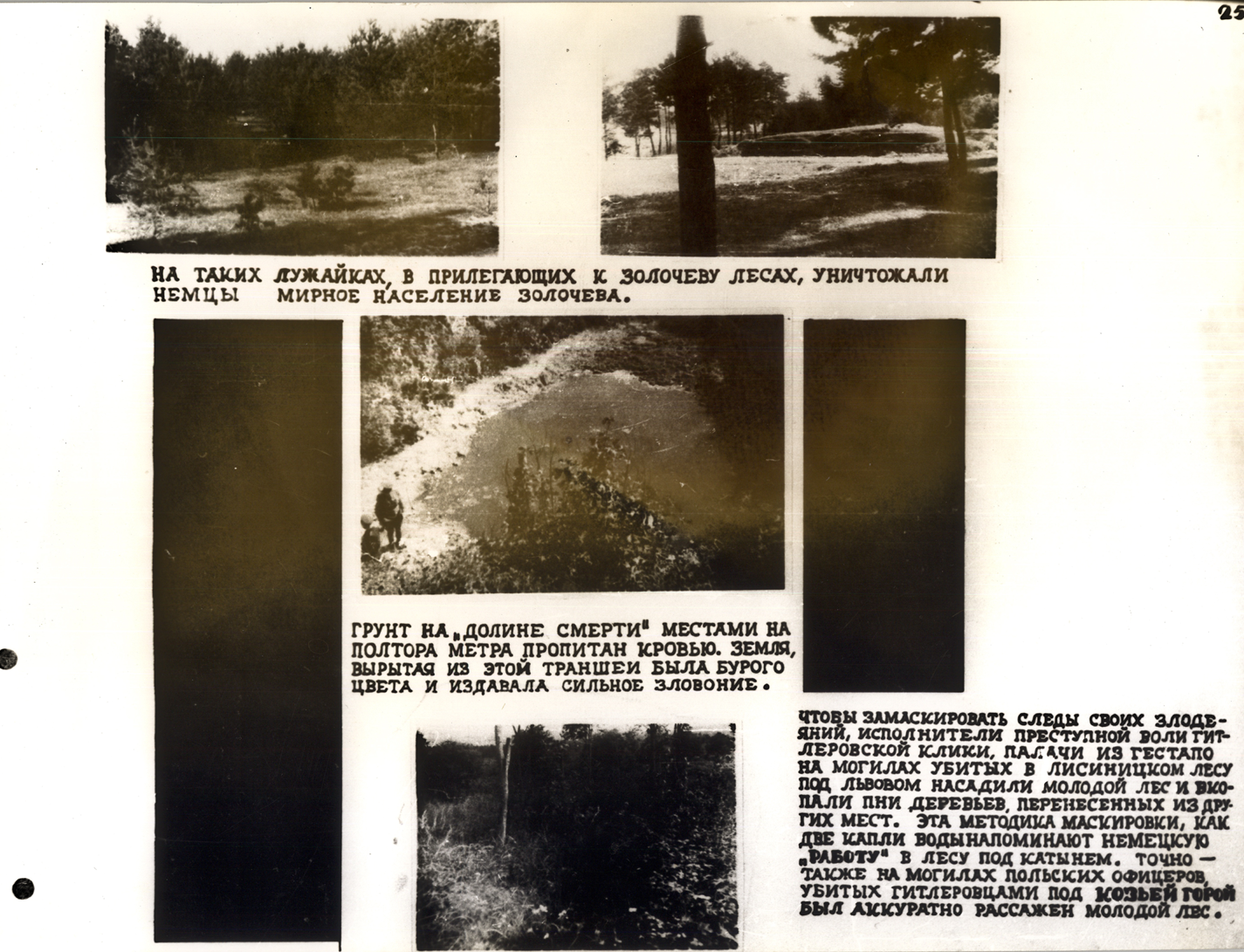

Researchers who wish to disentangle such links must begin by understanding the origins of the ChGK's photographs and other documentation. Herman Lewinter's oeuvre includes a photomontage devoted to his hometown of Zolochiv that focuses on trees planted to conceal mass graves. “This method of disguise resembles the German ‘work’ in the forest at Katyn like two drops of water,” the accompanying text reads. (Figure 6). In keeping with received wisdom, the copy of this photomontage in Lewinter's collection at USHMM would merit analysis into his motivation and creative process. The copy among the KGB's records, in contrast, probably would be dismissed as a top-down distortion, with some scholars reluctant to engage with such images at all. When treatment of the same source differs so greatly depending upon where it is accessed, new tactics are required. Approaching ChGK materials as diverse, often grassroots contributions promises to inject fresh insights into entrenched debates, even in the likely event that central KGB archives remain off-limits. Lewinter left behind no fewer than three oral histories that detail his perspective. Looking back, he depicts himself as “the last photographer” at Janowska, where he worked “so there should be a memory of what happened.” Yet Lewinter declined all requests to testify in West Germany due to concerns he would not be taken seriously, “even with the pictures.”Footnote 135 On that front, it is not too late to prove him wrong.

Figure 6. Photomontage composed by Herman Lewinter in the course of the ChGK investigation, c. September-December 1944. HDA SBU, f. 11, op. 1, spr. 988, t. 4, ark. 284.