Frontispiece 1. Excavation of a ‘schola' tomb discovered during work on the Pompeii Archaeological Park library building. The monument, dated to the Augustan period (27 BC–AD 14) is dedicated to Numerius Agrestinus; an inscription details his life and career. Among his various titles and roles, Agrestinus was a military tribune, prefect of the Autrygoni (a previously undocumented title), prefect of the engineers and was twice elected to the position of duumvir, one of the city’s two leading magistrates. Unusually, Agrestinus was already known from another funerary inscription erected by his wife, Veia Barchilla; the city council seems to have subsequently decided to honour Agrestinus with a second monument on public land. © Photograph courtesy of the Ministry of Culture-Pompeii Archaeological Park; reproduction prohibited.

Frontispiece 2. An 18m-long reconstruction of a Bronze Age ship undergoing sea trials off the coast of Abu Dhabi, UAE, in 2024. The vessel was built by shipwrights using traditional tools to a design based on information from Sumerian cuneiform tablets and ancient representations of boats typical of the land of Magan (modern-day Oman and the UAE). The hull of the wooden-framed vessel is made of 16 tonnes of reeds lashed together with palm-fibre rope and coated in bitumen; the sail is made of goat hair. During testing, the vessel reached speeds of 5.6knots. The ‘Magan Boat’ is the result of a collaboration between the Zayed National Museum, New York University Abu Dhabi and Zayed University. Photograph by E. Harris © Zayed National Museum.

Building for (an) eternity

![]() For an ancient and well-known city, there is always something new to discover in Rome. In late August, almost 5000 delegates gathered in the Eternal City for this year's annual meeting of the European Association of Archaeologists (EAA). Whether attending academic sessions or visiting sites, monuments and landscapes in and around the city, participants were left in no doubt about the scale of archaeological work underway in Rome today. The most prominent example relates to the long-running project for a new metro line that passes beneath the heart of the ancient city. As work proceeds on completing tunnels and stations, monuments such as the Basilica of Maxentius, propped up by scaffolding, are subject to careful monitoring for signs of subsidence caused by the works below. And it is underground that the real scale of the engineering—and the archaeological intervention—becomes apparent. Construction of the new station at Porta Metronia, for example, has involved the investigation of almost 50 000m3 of archaeological stratigraphy, in some places reaching more than 15m below current street level. At this station, excavations have revealed an early second-century AD military barrack block decorated with frescoes and mosaics, a large residential complex and a terraced garden all located on the edge of the ever-expanding imperial city. By the late third century, however, priorities had changed and the whole area was levelled during the hurried construction of the defensive Aurelian Walls around the city. Work on the new metro station required the complete removal of the surviving archaeological structures, but these will now be reinstalled in situ as part of a station/museum, one of several already completed or planned. Another stop along the line, the new station at San Giovanni, already offers commuters and visitors a fascinating display of finds recovered during the building works, while the stations under construction at the Colosseum and Piazza Venezia promise even more spectacular displays. The latter, for example, will incorporate parts of Hadrian's Athenaeum, or school for literary and scientific studies, discovered in 2009 during preparatory works for the metro. Visitors, and commuters, will need to wait a little longer for the first trains to arrive. Construction of the Piazza Venezia station, budgeted at approximately €0.75bn, finally began last year with a projected completion date of 2032.

For an ancient and well-known city, there is always something new to discover in Rome. In late August, almost 5000 delegates gathered in the Eternal City for this year's annual meeting of the European Association of Archaeologists (EAA). Whether attending academic sessions or visiting sites, monuments and landscapes in and around the city, participants were left in no doubt about the scale of archaeological work underway in Rome today. The most prominent example relates to the long-running project for a new metro line that passes beneath the heart of the ancient city. As work proceeds on completing tunnels and stations, monuments such as the Basilica of Maxentius, propped up by scaffolding, are subject to careful monitoring for signs of subsidence caused by the works below. And it is underground that the real scale of the engineering—and the archaeological intervention—becomes apparent. Construction of the new station at Porta Metronia, for example, has involved the investigation of almost 50 000m3 of archaeological stratigraphy, in some places reaching more than 15m below current street level. At this station, excavations have revealed an early second-century AD military barrack block decorated with frescoes and mosaics, a large residential complex and a terraced garden all located on the edge of the ever-expanding imperial city. By the late third century, however, priorities had changed and the whole area was levelled during the hurried construction of the defensive Aurelian Walls around the city. Work on the new metro station required the complete removal of the surviving archaeological structures, but these will now be reinstalled in situ as part of a station/museum, one of several already completed or planned. Another stop along the line, the new station at San Giovanni, already offers commuters and visitors a fascinating display of finds recovered during the building works, while the stations under construction at the Colosseum and Piazza Venezia promise even more spectacular displays. The latter, for example, will incorporate parts of Hadrian's Athenaeum, or school for literary and scientific studies, discovered in 2009 during preparatory works for the metro. Visitors, and commuters, will need to wait a little longer for the first trains to arrive. Construction of the Piazza Venezia station, budgeted at approximately €0.75bn, finally began last year with a projected completion date of 2032.

The new metro line is only one of many construction and renovation initiatives currently taking place in Rome. Ahead of next year's Jubilee, or Holy Year, the authorities are racing to complete hundreds of infrastructure projects to prepare the city for the arrival of millions of pilgrims. One of the largest interventions is the €70m pedestrianisation of Piazza Pia, which involves moving a five-lane road into a tunnel to allow visitors to walk unimpeded from Castel Sant'Angelo along the Via della Conciliazione to St Peter's Square. Excavations here have revealed a first-century AD fullonica for the processing and cleaning of textiles and gardens linked with the emperor Caligula. Coincidentally or otherwise, many of these recent investigations focus on the periphery of the ancient city, illuminating the suburban areas often omitted from studies of Roman urbanism.

With all of these projects underway, large parts of the city are currently concealed behind screens and hoardings (Figure 1). EAA delegates therefore did not have the opportunity to see the new and improved Rome set to be revealed for the Jubilee next year. But then Rome has been one great building site for the best part of three millennia. While scholarly studies typically focus on the completed architectural projects of emperors and popes, the experience of Rome's inhabitants was, and is, one of constant construction and reconstruction—a city in a perpetual state of becoming something else.

Figure 1. A screen conceals works underway on Via di S. Gregorio between the Palatine and Caelian hills, with the Arch of Constantine visible in the distance. Photograph by R. Witcher.

As a parting gift for EAA delegates, Rome offered one final spectacle. Just after the close of the conference, the week's scorching 37°C heat wave finally broke with a huge storm, dumping more than a month's worth of rain on the city in an hour and unleashing high winds that brought down trees and scaffolding. During the downburst, the Arch of Constantine was struck by lightning, sending lumps of marble tumbling to the ground.Footnote 1 The annals of ancient Rome list many examples of temples, houses and sculptures struck by lightning or damaged by storms, with doors ripped from their hinges, statues decapitated and trees uprooted. In Roman Antiquities, the first-century BC Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus recounts the importance of lightning and thunder as omens in the earliest (pre)history of the city. Storms were the medium that delivered the message, a means to communicate divine displeasure with human affairs. These messages required careful interpretation by the city's priests. The editor has no qualifications in such divination—duties typically require the interpretation of peer reviews rather than divine portents—but perhaps, in this case, we might venture that the medium is the message: a violent storm that is both a warning of anthropogenic climate change and the medium by which Gaia has expressed her concern. Rome has recently been held up by one scholar as an example of long-term urban resilience, reconciling significant vulnerability with sustainability, adapting over the centuries to outpace ecological, economic and political challenges.Footnote 2 But, as for many cities around the world, climate change now risks outpacing the ability of urban areas to adapt. Whether or not the gods really have spoken, the EAA meeting certainly ended with a bang! As a host city, Rome will be a hard act to follow; this Herculean task will be taken on by Belgrade in 2025, followed by Athens in 2026, Leiden in 2027 and Vienna in 2028.

Open access publishing

![]() The August editorial used the occasion of our 400th issue to look back over the Antiquity archive. Now, as our centenary year looms into view, it is also important to look ahead and here we take the opportunity to outline some of the initiatives underway to help shape Antiquity's future. At the heart of any journal are its contributors and readers, and we hope that these developments—some major, others modest, some immediate and others intended to bear fruit in the medium or longer term—will serve the Antiquity community well.

The August editorial used the occasion of our 400th issue to look back over the Antiquity archive. Now, as our centenary year looms into view, it is also important to look ahead and here we take the opportunity to outline some of the initiatives underway to help shape Antiquity's future. At the heart of any journal are its contributors and readers, and we hope that these developments—some major, others modest, some immediate and others intended to bear fruit in the medium or longer term—will serve the Antiquity community well.

The previous editorial explored how Antiquity has retained the core mission set out by the journal's founding editor, OGS Crawford: a global scope, a diversity of content and authoritative but accessible articles. At the same time, Antiquity has constantly evolved: its design and range of article types, the shift (for most readers) from print to digital, and the integration of social media as a means for engaging directly with our global audience. One development that would have fascinated Crawford is open access publishing. For decades, Antiquity editorials featured exhortations for subscribers to pay their dues and help keep the journal solvent. Today, by contrast, around 80 per cent of our research articles are published open access, removing the subscription paywall for readers and allowing anyone with an internet connection to access content. But, contrary to popular belief, open access does not mean ‘free’. There are still significant costs to be covered, including editorial staff, typesetters and proofreaders as well as submission systems, website hosting, doi numbers and so on. Today, it is no longer the subscribing reader that covers these costs but rather the author. Most Antiquity authors will find that their institution has an agreement with our publisher, Cambridge University Press, providing an automatic open access payment for their articles.Footnote 3 Instead of paying a subscription to allow their staff to read Antiquity, these institutions now effectively pay to allow their staff to publish with us, helping to remove the paywall for all readers in the process. Currently, authors without such an institutional arrangement can either pay an Article Processing Charge (APC) to make their article open access or publish it, without any fee, behind the paywall (though these authors may use ‘social sharing’ tools to help readers without a subscription).Footnote 4 But now, more than a decade since Antiquity published its first open access article, this hybrid situation of open access and paywalled articles will shortly come to an end.

In 2026, Antiquity will transition to a fully open access model, removing the paywall for all research articles. This is great news for readers, helping to make content more accessible than ever. It is also important for those authors whose funders mandate the open access publication of the research they sponsor. But what of those authors without publisher agreements or alternative sources of funding—particularly those from already under-represented parts of the world? Here, a partnership between the Antiquity Trust and Cambridge University Press has established a fund that will cover these costs: from 2026, all authors will be able to publish open access regardless of their institutional or financial circumstances. For a journal founded on a subscription model and where the subscriber/reader has always been at the heart of the journal's financial and philosophical model—including its proud claim of editorial independence—the transition to full open access publishing will be a significant step. It is, however, one that we believe works for both authors and readers, while also keeping the journal on a sustainable financial footing.

Credit note

![]() As well as open access publishing, OGS Crawford might have been surprised to learn of various other changes in the world of scholarly publishing, such as the rise of team authorship. The mean number of authors per article has increased from one in 1927 (indeed, all the contributions in volume 1 were single authored) to a mean of 6.5 authors per article in the current issue, ranging from a couple of single-authored articles to one with 25 authors (the latter is nothing unusual—an article in the August issue had 28 contributors). Such numbers, in part, reflect ever-growing specialisation within the discipline and hence the need for collaborative and interdisciplinary work; this is something Crawford would surely have welcomed, befitting his vision of Antiquity as a venue for bridge building between specialists. The growth in the numbers of authors per article in Antiquity, and in other archaeology journals, likely also reflects a trend towards the greater acknowledgement of the many ‘invisible labourers’ who contribute to archaeological knowledge through field and lab work.

As well as open access publishing, OGS Crawford might have been surprised to learn of various other changes in the world of scholarly publishing, such as the rise of team authorship. The mean number of authors per article has increased from one in 1927 (indeed, all the contributions in volume 1 were single authored) to a mean of 6.5 authors per article in the current issue, ranging from a couple of single-authored articles to one with 25 authors (the latter is nothing unusual—an article in the August issue had 28 contributors). Such numbers, in part, reflect ever-growing specialisation within the discipline and hence the need for collaborative and interdisciplinary work; this is something Crawford would surely have welcomed, befitting his vision of Antiquity as a venue for bridge building between specialists. The growth in the numbers of authors per article in Antiquity, and in other archaeology journals, likely also reflects a trend towards the greater acknowledgement of the many ‘invisible labourers’ who contribute to archaeological knowledge through field and lab work.

Even so, archaeology has not yet seen the sorts of author numbers that appear in some of the physical sciences where, sometimes, the author list is longer than the article itself. Here, the proliferation of authors can present challenges—not least, understanding who has contributed what. One solution is the Contributor Role Taxonomy, or CRediT, which provides a standardised list of 14 roles that can be used to describe the contributions made by individual co-authors. These roles include: Conceptualisation; Formal analysis; Visualisation; Writing—original draft; and Writing—review and editing. As a solution for a problem that is most common in the sciences, it is unsurprising that these descriptions are framed around scientific roles, but most of the tasks encountered on the typical archaeology project can be easily mapped across. The system is particularly valuable for early career researchers allowing them to record their specific contributions, especially important in support of tenure and promotion applications. It may also remove some uncertainty around the vexed question of author order. For these reasons, over the coming months, authors submitting to Antiquity will be able to start making use of the CRediT taxonomy.

Longer and more inclusive author lists may better reflect the collaborative nature of research, but they may also lead to misunderstandings or misuse, such as ‘gift authorship’ where researchers are added even though they have contributed little or nothing to the manuscript. Our publisher, like many others, now offers advice about how to determine who should, and should not, be listed as the author of an article.Footnote 5 Connected to this is, inevitably, the question of whether ChatGPT and other generative language models can be considered authors. In a word, no. Not least because one of the duties of an author is that they can take responsibility for an article's contents. Clearly, ChatGPT cannot do this. Nor is it able to generate the kinds of original research that Antiquity and other respected journals, and their readers, expect. Nonetheless, these rapidly evolving technologies may also present opportunities, for example, by helping the many contributors who have English as a second or third language (or ‘LX English’ users) to articulate their research.Footnote 6 You can find all of our policies, guidelines and other information about submitting your research to Antiquity at: https://antiquity.ac.uk/index.php/submit/guidelines

Rewriting world archaeology

![]() Many of the changes we have implemented over the past few years are small but signal important shifts in the nature of authorship or the use of language. For example, our style guide undergoes regular review to ensure that authors make use of appropriate and respectful language, including capitalising terms such as Black and Indigenous, and encouraging authors to avoid making assumptions about gender. Such changes are easy wins, but what about some of the bigger, systemic challenges, such as attracting more submissions on, and from, regions of the world that are under-represented in the pages of Antiquity? The question is not unique to this journal. For instance, in the past couple of years, the African Archaeological Review and the Journal of Archaeological Science have published analyses of the geographical focus of published content.Footnote 7 Notably, these studies reveal near identical distributions of research on African archaeology as that published in Antiquity: all three journals show concentrations that extend from Egypt south through East Africa, with a hotspot in southern Africa and a thin scatter across the rest of the continent (Figure 2).

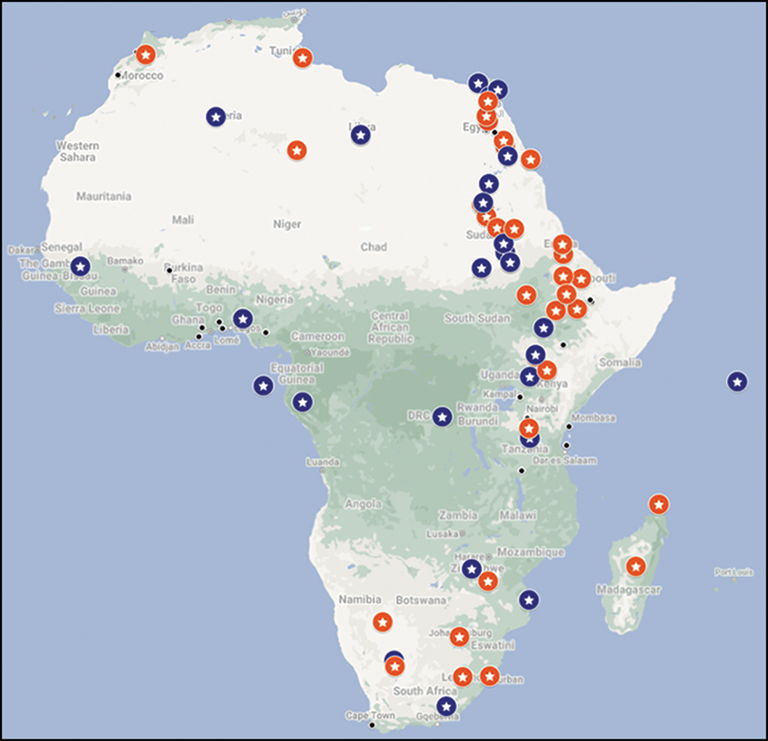

Many of the changes we have implemented over the past few years are small but signal important shifts in the nature of authorship or the use of language. For example, our style guide undergoes regular review to ensure that authors make use of appropriate and respectful language, including capitalising terms such as Black and Indigenous, and encouraging authors to avoid making assumptions about gender. Such changes are easy wins, but what about some of the bigger, systemic challenges, such as attracting more submissions on, and from, regions of the world that are under-represented in the pages of Antiquity? The question is not unique to this journal. For instance, in the past couple of years, the African Archaeological Review and the Journal of Archaeological Science have published analyses of the geographical focus of published content.Footnote 7 Notably, these studies reveal near identical distributions of research on African archaeology as that published in Antiquity: all three journals show concentrations that extend from Egypt south through East Africa, with a hotspot in southern Africa and a thin scatter across the rest of the continent (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Distribution of Antiquity content on African archaeology, 2018–2024: red = research articles; blue = Project Gallery articles; black = other editorial content.

If we then consider the authorship of these articles, the under-representation of African authors also becomes apparent. Although this situation is improving, with international teams of authors featuring more regional scholars, there are still significant challenges for archaeologists from Africa as well as places such as the Middle East and South and Southeast Asia. In a recent review of archaeological research in Africa, Chapurukha Kusimba observes welcome changes including the range of topics researched; however, some areas of concern are identified including ‘parachute science’ or ‘helicopter research’ and the disincentivisation of long-term engagement with African communities and their priorities.Footnote 8 Kusimba also summarises some of the initiatives intended to develop the capacity of African archaeology, including funding, training and institutional links. It is within this broad context of mentoring and capacity building that Antiquity has developed the ‘Rewriting World Archaeology’ (RWA) programme.

The origins of this initiative lay in the recognition of the relative lack of submissions from scholars based in certain parts of the world and of the problems that authors from these regions often encounter at the peer-review stage. For several years, we had offered ad hoc sessions for early career researchers (ECRs) at conferences such as the Society of Africanist Archaeologists (SAfA) meeting on writing for academic journals. Based on this experience, in partnership with colleagues from Bangladesh, India, Lebanon and South Africa, in 2021 we launched the RWA programme, funded by the British Academy (WW2021100224; PI Robin Skeates), to support 25 ECRs from Africa, the Middle East and South Asia, to develop academic-writing skills and expand their professional networks through a programme of online workshops and personal mentoring. Each ECR was assigned two mentors with a mix of specialist subject and editorial expertise, with one mentor from the ECR's study region and one from Europe or North America. Over the course of a year, our three regional groups of researchers worked on draft texts for submission to Antiquity or to other international, peer-reviewed journals.

The learning curve was as steep for us as it was for the ECRs, with the programme soon revealing the full extent of the many inter-related and varied challenges facing archaeological researchers in different parts of the world, including language barriers, lack of access to laboratories, and intermittent and unreliable electricity and internet. For many of the ECRs it has been a long and slow process to bring their research to publication, but we are now beginning to see the results in print. For example, Shatha Mubaideen's co-authored article on endangered archaeology in Jordan is published in Levant and Agnes Shiningayamwe's decolonising study of Namibia's cultural heritage database recently appeared in Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites.Footnote 9 We are very grateful to the three teams of mentors who contributed their time and expertise and to Kori Filípek for administrative support.

RWA South Asia and Africa workshops

![]() The original open call for participants received some 150 applications for just 25 places. This scale of demand, and the positive reception from the selected ECRs, their referees and regional mentors encouraged us to instigate two further rounds of workshops: one focused on ECRs from South Asia and the other for those based in Africa. Learning from our previous experience, we have refined the format and reset our expectations about time scales and the support needed. Another important difference is that, whereas the original workshops had to be conducted entirely online due to Covid-19 restrictions, the latest rounds have integrated in-person meetings.

The original open call for participants received some 150 applications for just 25 places. This scale of demand, and the positive reception from the selected ECRs, their referees and regional mentors encouraged us to instigate two further rounds of workshops: one focused on ECRs from South Asia and the other for those based in Africa. Learning from our previous experience, we have refined the format and reset our expectations about time scales and the support needed. Another important difference is that, whereas the original workshops had to be conducted entirely online due to Covid-19 restrictions, the latest rounds have integrated in-person meetings.

The first of the two to get underway, in late 2023, was the RWA South Asia programme, supported by funding from the Antiquity Trust, to work with 12 ECRs from India, Myanmar, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Tibet. As in the first programme, a series of online workshops covered topics such as what journal editors are looking for and guidance on the peer-review process—the latter a topic of perennial anxiety and misunderstanding, especially in research cultures where the practice is less common. Then, in March this year, the ECRs and mentors travelled to Kathmandu for a three-day workshop comprising presentations, peer-review exercises, one-to-one mentoring and intensive writing, all fuelled by significant quantities of dal bhat. There was also time to visit some of Nepal's cultural heritage including the Durbar Squares of Hanuman Dhoka (Kathmandu) and Lalitpur (Patan) and the Pashupatinath Temple, all part of the Kathmandu Valley World Heritage Site (Figure 3). It can be difficult to quantify the added value of such in-person meetings in order to justify the costs involved but the ECRs and mentors were in unanimous agreement on the benefits of gathering in one place to focus intensively on research and to spend time informally building networks and sharing new experiences. The ECRs and mentors are now working through the detailed feedback provided in Kathmandu and looking towards the submission of manuscripts to their chosen journals. We are very grateful to the mentoring group including Mr Kosh Acharya, Prof. K. Krishnan, Prof. Shahnaj Jahan, Prof. Shanti Pappu and Durham colleagues, to our Nepali hosts, and to Dr Armineh Kaspari-Marghussian for administrative support.

Figure 3. Early career researchers and mentors at the Rewriting World Archaeology: South Asia workshop, visiting the Hanuman Dhoka complex in Kathmandu, March 2024. Photograph by A. Kaspari-Marghussian.

Meanwhile, our RWA: Africa programme is generously supported by funding from the British Academy (WWAF\100023 PI Robert Witcher) and is supporting eight ECRs from Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa and Sudan. Again, we have been running a series of online workshops, including the opportunity to put questions to the editors of African and world archaeology journals, including Dr Tunde Babalola and Prof. Peter Mitchell. In September, the whole group then met for an in-person workshop in Nairobi hosted at the British Institute in Eastern Africa (Figure 4). Over three days, the ECRs and mentors worked intensively on the draft manuscripts to prepare them for submission. We were joined virtually by some of the first cohort of ECRs from the RWA workshops who talked about their experiences and, serendipitously, we were also invited to attend a reception at the Nairobi National Museum hosted by colleagues from the ‘Mapping Africa's Endangered Archaeological Sites and Monuments’ project (https://maeasam.org). We are enormously grateful to our mentors, Dr Elgidius Ichumbaki, Dr Abigail Moffett, Prof. Innocent Pikirayi and Dr Nancy Rushohora, plus colleagues from Durham University, as well as all those who have contributed to the online sessions over the past year. Our thanks also go to Dr Kennedy Gitu and Loice Anyango at the British Institute in Eastern Africa, and to Jane Abel for administrative support.

Figure 4. Early career researchers and mentors at the Rewriting World Archaeology: Africa workshop held at the British Institute in Eastern Africa in Nairobi in September 2024. Photograph by C. Mwaniki.

If world archaeology is to be more than an accumulation of case studies from around the globe and is, instead, about engaging with a diverse range of perspectives and research traditions, it is essential that the voices of scholars from currently under-represented regions are more central in the international literature. The RWA programme is a very modest contribution towards this goal. Our hope is that by building equitable partnerships and working with ECRs to demystify the publication process, develop research and writing skills, to expand professional networks and to grow confidence, these researchers will see their work published in high-profile journals and read by global audiences. But beyond that, we hope that these individuals have the potential to become future leaders within the discipline and to reshape the archaeological agenda.

In this issue

![]() The current issue features 13 research articles, two debates pieces, six Project Gallery articles and reviews of more than a dozen books. The research articles cover topics ranging from the initial phases of sedentism in Central Anatolia in the late ninth millennium BC (Goring-Morris et al.) through to evidence for the ‘crowded’ settlement landscape of the central Maya Lowlands (Auld-Thomas et al.). Two articles explore aspects of ancient textiles, in Iron Age France (Bertrand et al.) and tenth-century AD highland Peru (Quilter et al.). We also return to the Tollense Valley for further insights into Bronze Age Europe's most famous battle (Inselmann et al.) and to the site of Bangga in Tibet for new evidence about high-elevation prehistoric agropastoralism (Liu et al.). Other articles explore how UK museums communicate ideas about religious practice in Roman Britain (Lee), the debate about restitution and repatriation of objects to Southeast Asia (Murphy), the DNA metabarcoding of coprolites (Johnson et al.), and a re-evaluation of the origins of Greek Protogeometric pottery, shifting the earliest examples back in time and northwards into Macedonia (Van Damme & Lis). In the debate section, Bentley & O'Brien revisit the role of cultural evolutionary theory in archaeology, with responses from four invited commentators. We also feature a carb-fest of articles on food production: the cultivation of broomcorn millet in Bronze Age Anatolia (Maltas & Günel); the expansion of rice agriculture in Japan during the first millennium BC (Crema et al.); and the pre-Columbian spread of American sweet potato across southern Polynesia (Barber & Benham). Finally, we are excited to include an article presenting the first evidence for sedentary farmers in Bronze Age Mediterranean Africa, filling a significant chronological and cultural gap in our understanding of this region (Broodbank et al.). As ever, we hope that this issue provides something for all tastes and dietary preferences!

The current issue features 13 research articles, two debates pieces, six Project Gallery articles and reviews of more than a dozen books. The research articles cover topics ranging from the initial phases of sedentism in Central Anatolia in the late ninth millennium BC (Goring-Morris et al.) through to evidence for the ‘crowded’ settlement landscape of the central Maya Lowlands (Auld-Thomas et al.). Two articles explore aspects of ancient textiles, in Iron Age France (Bertrand et al.) and tenth-century AD highland Peru (Quilter et al.). We also return to the Tollense Valley for further insights into Bronze Age Europe's most famous battle (Inselmann et al.) and to the site of Bangga in Tibet for new evidence about high-elevation prehistoric agropastoralism (Liu et al.). Other articles explore how UK museums communicate ideas about religious practice in Roman Britain (Lee), the debate about restitution and repatriation of objects to Southeast Asia (Murphy), the DNA metabarcoding of coprolites (Johnson et al.), and a re-evaluation of the origins of Greek Protogeometric pottery, shifting the earliest examples back in time and northwards into Macedonia (Van Damme & Lis). In the debate section, Bentley & O'Brien revisit the role of cultural evolutionary theory in archaeology, with responses from four invited commentators. We also feature a carb-fest of articles on food production: the cultivation of broomcorn millet in Bronze Age Anatolia (Maltas & Günel); the expansion of rice agriculture in Japan during the first millennium BC (Crema et al.); and the pre-Columbian spread of American sweet potato across southern Polynesia (Barber & Benham). Finally, we are excited to include an article presenting the first evidence for sedentary farmers in Bronze Age Mediterranean Africa, filling a significant chronological and cultural gap in our understanding of this region (Broodbank et al.). As ever, we hope that this issue provides something for all tastes and dietary preferences!