Introduction

The killing of Cecil the Lion generated immense media attention and public interest, and for many in the conservation movement it also created an opportunity to push for policy change. Despite the persistent efforts of conservation advocates to raise the public salience of species decline, for many people around the world issues such as habitat loss, illegal wildlife trade and trophy hunting rarely garner much attention. The high-profile nature of Cecil's killing thus created a moment of intense attention to the issue of lion Panthera leo conservation. Scholars of public policy often refer to such moments as focal events, which alongside other factors can create a policy window, during which the conditions for policy reform are particularly favourable.

Here we examine the Cecil the Lion incident to determine whether the attention it generated prompted governments to adopt new policies regarding the trophy hunting of lions. We find evidence that the Cecil case created an intense but brief period of public attention around the world, consistent with how public policy scholars conceive of focal events. However, we also find that this surge in public attention did not lead to major policy changes in most of the eight countries (USA, Spain, France, Russia, Canada, South Africa, Germany, Mexico) where the importation of lion trophies is especially common. The primary contributions of this study are twofold. Firstly, we illustrate the use of internet search activity as a tool to identify the type of focusing events important in public policy scholarship. Secondly, we bring core public policy theories to the conservation literature through our evaluation of the policy impact of the Cecil incident.

The balance of the article is organized as follows. Firstly, we describe Cecil's death and the media coverage it generated. We then summarize leading theories of policy change to provide a theoretical framework from which we can generate expectations about the policy impact of the Cecil case. Next, we discuss our research design, including how we measure public attention to the Cecil incident and any resulting policy changes. We then describe the results of our study of policy in eight countries, which includes a more detailed examination of the USA. We conclude with our analysis and conclusions.

Background

Cecil was a 13-year-old lion, and one of the top tourist attractions in Zimbabwe's Hwange National Park. His popularity has been attributed to a combination of his belonging to a charismatic species and his large size, black mane, tolerance of tourist vehicles, and possession of an English nickname (Bittel, Reference Bittel2015). On 1 July 2015 Walter James Palmer, an American dentist and avid bowhunter, killed Cecil for a trophy (Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Thornycroft and Laing2015).

National Geographic first reported Cecil's death on 21 July 2015, and within days the incident became the focus of intense news coverage and social media interest (Macdonald et al., Reference Macdonald, Jacobsen, Burnham, Johnson and Loveridge2016). Initial reports (some of which contained erroneous or exaggerated information) stated that Cecil had been lured out of a national park, shot with an arrow to avoid detection, suffered for more than 40 hours before being killed with a rifle shot, and had his collar removed illegally to hide his death (BBC, 2015; Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Thornycroft and Laing2015; Rogers, Reference Rogers2015). On 27 July the media identified Palmer as the hunter, and a day later Zimbabwe's National Parks proclaimed that Palmer's guide was facing charges for having conducted an illegal hunt (Melvin, Reference Melvin2015). Celebrities began tweeting about Cecil's killing that same day, and Jimmy Kimmel, a popular late-night television host, gave an impassioned monologue about it that night (Macdonald et al., Reference Macdonald, Jacobsen, Burnham, Johnson and Loveridge2016).

The fame accompanying Cecil's death can probably be attributed to a combination of factors. Because of their size, charisma and popularity, conservation groups often use lions as a flagship species to raise awareness of and support for conservation issues (Caro et al., Reference Caro, Engilis, Fitzherbert and Gardner2004; Macdonald et al., Reference Macdonald, Burnham, Hinks, Dickman, Malhi and Macdonald2015). The initial reports of Cecil's death also contained a number of salacious details, in that he ‘was allegedly lured to [his] death…endured a lingering death, was killed in apparently dubious circumstances, by a client who was identifiable…wealthy, white, male and American and who, to judge by media reports, had previously been associated with problematic hunting episodes’ (Macdonald et al., Reference Macdonald, Jacobsen, Burnham, Johnson and Loveridge2016).

The attention surrounding Cecil's death was significant. Macdonald et al. (Reference Macdonald, Jacobsen, Burnham, Johnson and Loveridge2016) determined that during 1 July–30 September 2015 Cecil the Lion generated a total of 94,631 distinct editorial news items and 695,983 distinct social media posts across 125 languages. The spike in attention was generally consistent across the world but was also short-lived, having diminished to near pre-incident levels in just a few months.

From a policy standpoint, an important question is whether the high-profile killing of Cecil raised public interest in lion conservation and, specifically, led to reforms pertaining to trophy hunting. Scholars of public policy emphasize the role of causal stories as being important for setting agendas (Stone, Reference Stone1989) and creating the impetus for collective action (Mayer, Reference Mayer2014), and the killing of Cecil the Lion appears to be the type of causal story that can quickly raise the profile of an otherwise low-salience issue. Scholars often highlight the important role of these types of cases as focusing events that can play a crucial role in policy shifts.

Literature review

It is commonly observed that public policy is characterized by long periods of minor, incremental change interrupted by infrequent and abrupt policy shifts. Known as punctuated equilibrium, this phenomenon is seen across a range of policies, countries and government types (Baumgartner & Jones, Reference Baumgartner and Jones1993; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Baumgartner, Breunig, Wlezien, Soroka and Foucault2009; Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Foucault and François2012; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Flink and King2014; Lam & Chan, Reference Lam and Chan2015). The seemingly paradoxical tendency of policy to experience both incremental and sudden change is attributed to both institutional factors and the fact that policymakers of all types face logistical and cognitive limitations.

Lindblom (Reference Lindblom1959) proposes a model of policymaking in which policymakers have temporal, financial and mental constraints that prevent them from engaging in the rational consideration of all possible policy options. Consequently, rather than constantly remaking policy anew, policymakers instead ‘muddle through’ by making small changes to existing policy. This type of decision making tends to lead to incremental policy shifts, but it does not explain why policy periodically undergoes major changes.

Baumgartner & Jones (Reference Baumgartner and Jones1993) argue that these abrupt policy transitions, which they characterize as ‘shift[s] from one point of stability to another,’ are the result of breakdowns in ‘policy monopolies.’ These monopolies are coordinated groups of actors who succeed in influencing policymaking. Although ordinarily stable, policy monopolies can become stressed, allowing other actors the opportunity to influence policy decisions. During these periods of disequilibrium, policy issues are forced onto a broader political agenda (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Jones, Mortensen, Sabatier and Weible2014).

The instability of a policy monopoly is closely tied to the definition of the issue that the policy is meant to address. Proponents use these policy images—combinations of empirical information and emotive appeals—to advocate for a particular policy outcome (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Jones, Mortensen, Sabatier and Weible2014). Focusing events can help change the policy image around an issue, and it is at these moments of instability when advocates can be successful in moving policy in a new direction.

Kingdon's (Reference Kingdon1995) model emphasizes the fleeting nature of these opportunities for change. He conceives of three temporal streams that constitute policymaking: problems, policies and politics. The problem stream consists of issues identified by the public or government as problematic, often in response to some sort of focusing event. The policy stream includes policy alternatives and their advocates, who work to interest policymakers in particular policy approaches. The politics stream represents the political circumstances that influence whether a problem is embraced by policymakers as needing a solution.

In this multiple-stream model, Kingdon argues that policy change is most likely to occur when these three normally independent streams converge temporarily: focus turns to a problem, it captures the attention of policymakers, and an acceptable policy alternative is presented. During these brief moments, which Kingdon refers to as policy windows, policy entrepreneurs attempt to couple the streams to effectuate the desired policy change. At the close of these policy windows, the attention of the policymakers and public turn to other perceived problems, the streams separate again, and policy change becomes unlikely (Kingdon, Reference Kingdon1995).

Birkland (Reference Birkland1998) concentrates more closely on the focusing events that can help trigger policy windows. He defines a focusing event as an event that is ‘sudden; relatively uncommon; can be reasonably defined as harmful or revealing the possibility of potentially greater future harms; has harms that are concentrated in a particular geographical area or community of interest; and that is known to policymakers and the public simultaneously.’ Birkland contends that the suddenness of the focusing event (and hence the inability of the policy monopoly to prepare a response) evens the playing field between established interests and those advocating for policy change. Nevertheless, an advocacy coalition must quickly capitalize on a focusing event or it will fade from the public consciousness (Birkland, Reference Birkland1998).

Although the paradigmatic focusing event is of short duration (Kingdon, Reference Kingdon1995), scholars have also identified the possibility of aggregate focusing events, in which the accumulation of otherwise minor events can draw public attention to an issue (Birkland, Reference Birkland1997; O'Donovan, Reference O'Donovan2017). Thus, it is possible that Cecil's death could be the beginning of an aggregation effect, particularly given the (heretofore much less intense) news coverage in July 2017 that Cecil's son was also killed by a trophy hunter. Nevertheless, here we are interested in the effects of Cecil's death as a singular focusing event.

Scholars of public policy have identified numerous focusing events in the area of environmental policy, including catastrophes such as the Exxon Valdez and Deepwater Horizon oil spills and industrial accidents such as the nuclear meltdown at Three Mile Island and the fatal gas leak at the Union Carbide plant in Bhopal. To our knowledge, no previous single event in the domain of wildlife conservation has been broadly conceived as a focusing event, at least at a scale that might have contributed to major policy change. Yet, several notable voices in the conservation movement have suggested that the killing of Cecil the Lion may be just such an event (Allison, Reference Allison2015; Goode, Reference Goode2015; Macdonald et al., Reference Macdonald, Jacobsen, Burnham, Johnson and Loveridge2016). This study examines that possibility.

Methods

To investigate the role of Cecil the Lion's death as a potential catalyst for policy change, we analyse whether his killing (1) can be considered to be a potential focusing event, and (2) resulted in any tangible policy change. We use two analytical tools in this evaluation. Firstly, we examine internet search activity to assess whether Cecil the Lion's death focused public attention. Secondly, we measure recent adoptions of laws impacting trophy imports in the countries that most frequently import lion trophies, with a more detailed look at proposed and enacted changes to import policies in the USA. We focus on trophy importation policy, as much of the public interest in Cecil's death arose from the fact that he was killed as a trophy, rather than for his meat, to prevent livestock predation, or for some other reason. Moreover, we analyse the policies of demand-side importers because trophy hunting tends to be more controversial in developed countries (from which most trophy hunters hail), than it is in many lion range states, where the practice can generate significant income.

To select countries for our analysis we relied on data maintained by CITES (2016) to determine the largest importers of lion trophies (we identified as an individual trophy a lion carcass or any part of a carcass, such as bones, teeth, claws or skin). Because of disparities in the number of trophies listed by importing and exporting countries (i.e. importing countries often stated significantly lower trophy imports than the total indicated as being shipped to them by exporting countries), we used exporters’ data to determine this ranking.

We focus our attention on the top 10 importing countries, which are, in order, the USA, Spain, France, Russia, Canada, South Africa, Germany, Mexico, China and the Czech Republic. The USA is by far the largest importer of lion trophies (Table 1). During 2004–2014 it imported 7.5 times as many lion trophies (7,586) as the next highest importer (1,002), and more than twice the combined total of all the other countries analysed. Beyond these 10 nations, the next two highest importers were Norway and Laos, with 144 and 142, respectively. The remaining countries of the world each imported fewer than 125 lion trophies during this period (and 2,189 in total).

Table 1 Total lion Panthera leo trophy imports (and percentage of imports worldwide) in the top 10 importing countries during 2004–2014, from the CITES (2016) trade database.

Internet search activity

To evaluate whether the killing of Cecil the Lion can reasonably be characterized as a focusing event, we used Google Trends (2017) to measure public interest in the aforementioned countries. From the resulting data we can infer whether public attention spiked in such a way that we can reasonably conclude that the event focused attention on lion conservation and trophy hunting.

For a given time period, Google Trends uses a random sample of user data to identify the week with the highest search frequency and provides a relative value for the remaining weeks in the period. Values are normalized to a 0–100 scale, with 100 indicating the highest relative search frequency. Each data point is weighted according to location, so that locations within the search with a higher density of internet users do not skew the results.

Google Trends data have been found to be a valid, reliable measure of public attention and issue salience when compared to traditional methods of measurement (Ripberger, Reference Ripberger2011; Mellon, Reference Mellon2014). A number of studies have used these data to assess public interest (Mellon, Reference Mellon2014), including to measure interest in environmental issues (Mccallum & Bury, Reference Mccallum and Bury2013; Andrew et al., Reference Andrew, Arndt, Beristain, Cass, Clow and Colmenares2016; Nghiem et al., Reference Nghiem, Papworth, Lim and Carrasco2016). Of particular relevance to this study, Anderegg & Goldsmith (Reference Anderegg and Goldsmith2014) and Cha & Stow (Reference Cha and Stow2015) evaluated change in public attention to environmental issues in response to particular events. However, other than Kastner's (Reference Kastner2016) discussion of the creation of the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, we are not aware of any studies that have used Google Trends as part of an analysis of public policy adoption.

Within Google Trends, users can employ a topic search to examine the worldwide search frequency of clusters of topically related searches. In the topic search, Google uses an algorithm to aggregate related searches, including different syntax and spelling, across various languages. In this case we relied on an existing topic search created by Google titled Killing of Cecil the Lion. Specifically, we analysed these data for each of the selected countries to obtain a maximum normalized score of 100 for each country. When a Google Trends search includes multiple jurisdictions, each jurisdiction is scored relative to the one with the highest relative search frequency. By conducting a separate search for each of the selected countries we were able to measure the relative increase in interest within each of the selected countries, rather than changes in their comparative topical search frequencies.

Although the use of a topic search has the drawback of preventing us from knowing exactly what related searches are included, it is reasonable to assume that it includes alternative search terms such as ‘Cecil the Lion death’ or ‘Cecil killed.’ We also conducted our own Google Trends analysis using the following worldwide English language search terms: ‘lion conservation,’ ‘trophy hunting,’ ‘Cecil the Lion,’ ‘are lions endangered,’ and ‘lion hunting.’ These searches produced results consistent with those generated by Google's topic search.

The topic search option has the benefit of a single search encompassing the myriad search terms and languages that internet users might use to search for the killing of Cecil the Lion. As such, for the purposes of this analysis, the benefits of this increase in analytical power outweigh the drawbacks of not knowing exactly which languages and syntax are included in the search. Another limitation to the Google Trends tool is that it does not perfectly measure internet search activity everywhere in the world. Consequently, we lacked the data to conduct an analysis in two of the 10 countries (China and the Czech Republic) we originally selected for this study.

Trophy importation policy

We examine adoptions of policies to restrict trophy importation at the national level for the top eight lion importing countries for which Google Trends data are available. It is important to emphasize that we are not making any assertion as to whether trophy import bans were the ‘correct’ policy response, as there is an active debate among conservation scholars and practitioners about the value of regulating trophy hunting (e.g. Treves, Reference Treves2009; Di Minin et al., Reference Di Minin, Leader-Williams and Bradshaw2016a, Reference Di Minin, Leader-Williams and Bradshawb; Lindsey et al., Reference Lindsey, Balme, Funston, Henschel and Hunter2016; Ripple et al., Reference Ripple, Newsome and Kerley2016). We do not take a position in this debate here; we simply suggest that trophy importation limits were a plausible response to the killing of Cecil.

No single source of information on trophy import laws exists, so we conducted original data collection to identify changes in policy. We began with searches of databases maintained by the European Union and CITES, and of news articles and blog posts from various websites, including those geared towards both hunting and wildlife protection. We then queried policy experts from groups spanning the political spectrum, including policy advocates from organizations both opposing and supporting the continued hunting of lions and other wildlife.

We supplemented this national-level review with a more detailed review of proposed changes to trophy importation laws in the USA. Specifically, we searched national and state legislative archives for terms such as ‘lion,’ ‘endangered,’ and ‘wildlife.’ Where archives were organized by topics (such as wildlife or animals) we reviewed all legislation within those topics. In addition to the above search terms, we searched federal legislation using each of the terms ‘trophy hunting,’ ‘poaching,’ and ‘hunting’ in combination with the term ‘endangered species.’ We reviewed all proposed legislation for the period 2010–2016, to capture laws proposed in the years prior to the killing of Cecil and in the following year.

Our data collection was organized to measure whether the Cecil case materialized into a focusing event, and to identify changes in lion trophy importation policy in countries where such importation has historically been most frequent. We can then analyse the information to draw some conclusions about whether Cecil's death generated sufficient attention around trophy hunting to garner a policy response. It is important to emphasize that this research is not designed to make any causal claims regarding whether policy changed as a direct result of the Cecil incident. We also cannot delineate the mechanisms by which policy change did or did not occur, including the role of specific policy advocates and policy coalitions. We think it is likely that some advocates actively sought to use Cecil's death to effectuate policy change, but evaluating the role of policy actors in using the Cecil the Lion incident to advocate for policy change is beyond the scope of this study.

Results

Firstly, we report our results on cross-national internet search activity to determine whether it suggests that the Cecil case represented a policy focusing event. We then describe changes in lion trophy importation policy in the countries analysed.

Internet search activity

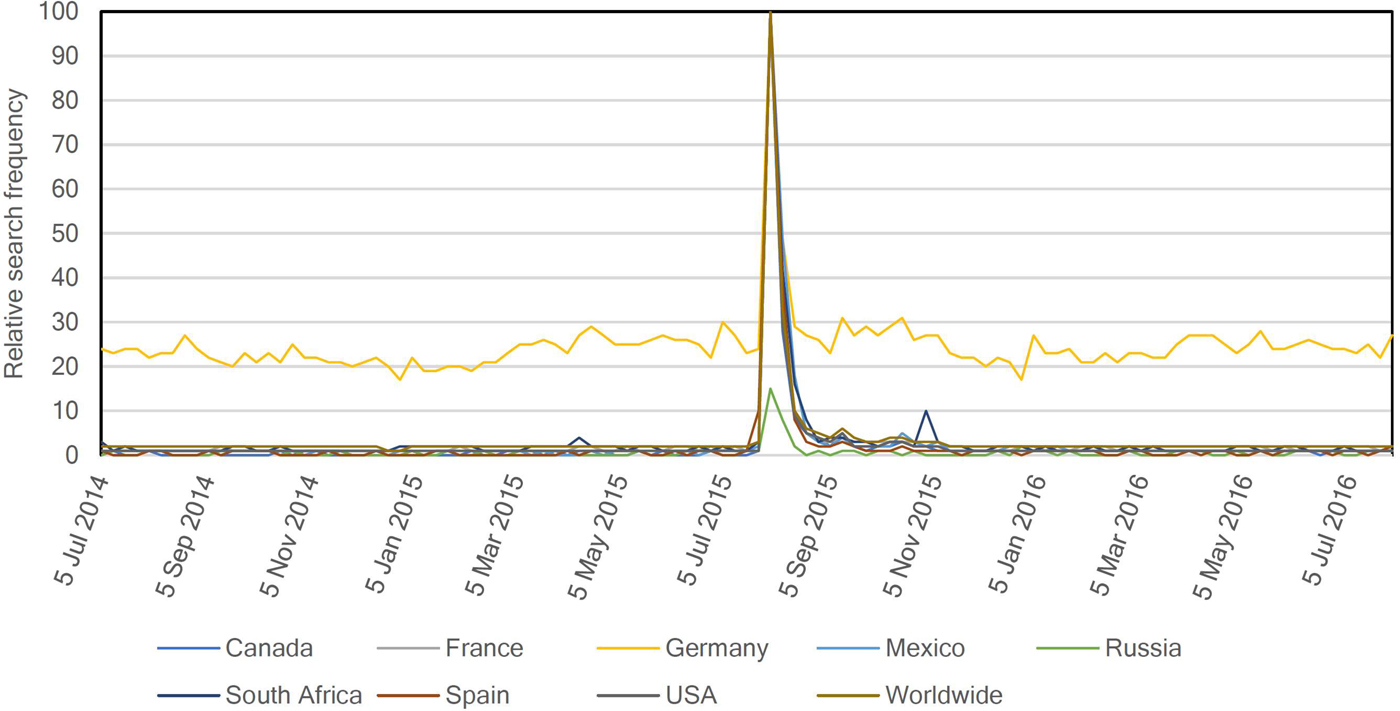

Figure 1 displays results from the Google Trends analysis for the year prior to and the year after the Cecil incident. The relative frequency of topical searches for ‘Killing of Cecil the Lion’ increased sharply during 25–31 July 2015, the week following National Geographic's reporting of the killing of Cecil. The spike is evident at both the worldwide level and in each of the eight countries in our study. Moreover, during that week each of the countries except Russia experienced its highest peak in search frequency over the entirety of the c. 12-year observation period. Supplementary Fig. S1 displays these data for the full period available in the Google Trends analysis (2004–2016), and the raw data are in Supplementary Table S1.

Fig. 1 Results from the Google Trends analysis showing the relative frequency of topical searches for ‘Killing of Cecil the Lion’ in the year prior to and the year after Cecil was killed.

Aside from Russia, the pattern of internet search activity shows a rapid decline after this initial week. During 1–8 August 2015 the relative worldwide search frequency dropped by two thirds, from 100 to 33. Search activity in the observed countries dropped in frequency by approximately 50% or more, with Canada experiencing the largest drop (73%). This decline continued in the third week after Cecil's death. During 9–15 August the worldwide search frequency dropped from 33 to 10, and the relative search frequency for the week in the focal countries was 8–29% of that in the first week.

The frequency of topical searches continued to decline over the course of the next year. Although the mean frequency for the worldwide and most of the country-specific searches remained slightly elevated for the next 6 months, after that they returned to at or near their historical pre-incident levels. These data show a similar pattern to the intense but short-term media coverage of the killing of Cecil (Macdonald et al., Reference Macdonald, Jacobsen, Burnham, Johnson and Loveridge2016).

Policy changes in high import countries

Our review of policy changes in the eight countries found three major reforms that potentially impact the import of lion trophies, one of which occurred prior to Cecil's death, and two afterwards. These three cases are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2 National policy changes in countries with high imports of lion trophies, before and after the killing of Cecil the Lion.

In February 2015, 4 months before the Cecil incident, the EU enacted a new policy to require the issuance of import permits for lion trophies (along with five other species) only after a demonstration that the activity meets a set of sustainability criteria. This policy affects four of the countries in our study: Spain, France, Germany and the Czech Republic. Specifically, lion trophies are no longer exempt from import permits as personal effects. Instead, these trophies are treated as though they come from the EU's Annex A, which means that an import permit may be granted only if, among other things, it would not have a harmful effect on the species’ conservation (European Commission & TRAFFIC, 2015).

After Cecil's death, there were two notable national-level policy changes in the eight countries we examined. France issued a ban on lion trophy imports in November 2015. The country's environment minister, Ségolène Royal, stated the change in policy in a letter to actress Brigitte Bardot, whose foundation focuses on animal protection (Royal, Reference Royal2015). Minister Royal advised that she had issued a directive to immediately cease the issuance of any import permits for lion trophies, and that she favoured the adoption of stronger controls on trophy imports more broadly.

In the USA the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed lions as threatened, under the Endangered Species Act. This action does not prevent the importation of lion trophies, but the listing requires that permits be granted only upon showing that the import will enhance the survival of the species. Although the final decision to list lions as a threatened species came 5 months after the Cecil incident, the original petition to do so was filed with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in March 2011, and a rule was proposed in 2014 to list the lion as threatened (USFWS, 2015).

It is worth noting that in the course of our research we also identified proposed and actual policy changes that fall outside the scope of our study. India issued a circular in February 2014 that capped trophy imports for non-Annex I species. Australia decided in March 2015 to treat lion trophies as being listed under CITES Annex I rather than the less stringent Annex II. In April 2016 the Netherlands issued a ban on the importation of trophies of 200 wildlife species, including lions. At the 17th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to CITES, the EU introduced a proposal that would have required both that export permits be issued for all trophies and that the permits would be issued only upon satisfaction of certain enumerated conditions. On 21 October 2016 the USA also banned all imports of lion trophies from canned hunts. Although this ban will certainly disrupt the import of lion trophies into the USA, the impact of the ban is limited to trophies of captive animals that are hunted within enclosures. Beyond formal government policy, more than 40 airlines adopted or reaffirmed bans on the shipment of animal trophies in the months following Cecil's death.

Additional policy changes in the USA

As the USA accounted for more than half of all lion trophy imports during 2004–2014, in this section we take a closer look at federal and state-level legislative policy change in the country during the 6-year period 2010–2016.

We identified four proposed bills at the federal level that would have potentially impacted the import of lion trophies (Table 3). The proposed Enhancement of Species Survival Act was the only bill that pre-dated Cecil's death, and it would have required that trophy import permits be granted for species listed as threatened or endangered under CITES if the trade in the trophy was in accordance with CITES requirements. The remaining three bills were proposed in the months after Cecil's death, and each mentioned Cecil's name explicitly in their titles. House Resolution 3448 would have prohibited the import of any species listed as endangered or threatened, by eliminating the ability of the Secretary of Commerce to issue import permits. Senate Bill 1918 and House Bill 3526 were identical companion bills and sought to extend the existing prohibitions on the import of trophies of endangered and threatened species to include species proposed to be listed under the Endangered Species Act (at the time these bills were introduced, no decision had been made on the petition to list lions as a threatened species). None of these bills were debated formally, voted on, or became law.

Table 3 Legislation on wildlife trophy imports introduced in the U.S. Congress during 2010–2016.

At the state level we identified nine proposed bills that would have impacted imports of lion trophies (counting partner bills filed in both houses as a single bill). As Table 4 shows, Illinois Senate Bill 2846 largely mirrored the federal House Bill 3526 in that it would have prohibited the import of endangered and threatened species as well as species proposed to be listed as such. The remaining eight bills all sought specifically to protect lions along with other species. All but one (Pennsylvania) proposed banning the sale or purchase of the protected species. The proposed bills in five of the eight states (Connecticut, Illinois, New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania) would have also prevented any import of the species. Only Hawaii and New Jersey adopted these proposed measures into law.

Table 4 Legislation on wildlife trophy imports introduced in the U.S. State Legislatures during 2010–2016.

Discussion

The evidence presented in the Results leads us to the following two conclusions: Cecil's death was a focusing event that triggered a potential policy window in several countries; and the Cecil incident did not elicit a large-scale change in policy, although it may have hastened policy reforms in some countries.

The killing of Cecil the Lion satisfies all five elements of Birkland's (Reference Birkland1998) definition of a focusing event. It was sudden and, although lion trophy hunting itself is not uncommon, news coverage of the scale that occurred was certainly exceptional. Rather than an isolated event, Cecil's death was discussed in the wider context of the controversial trophy hunting industry, often with further discussions of recent declines in global lion populations (Howard, Reference Howard2015; Melvin, Reference Melvin2015). The fact that Cecil was a lion provided conservation and animal rights activists with a common focal point for concern and advocacy, and widespread media coverage of the event meant that both the public and policymakers became aware of Cecil's death simultaneously.

Our Google Trends analysis suggests that the general public responded to the event with a strong, albeit temporary, increase in interest in Cecil's killing. Worldwide topical searches immediately after the incident were > 50 times greater than in the previous 2 years and c. 24 times greater, on average, in the eight countries analysed. Yet, within 3 weeks of the first news coverage of the event, public interest receded rapidly to near pre-incident levels. In the analysed countries the average level of internet search activity in the 6 months following Cecil's death (excluding the initial 2-week period) was a mere 5% of its post-death peak. During the 6–12 months after Cecil's death, public interest was only marginally higher than in the 24 months prior to the incident.

It is more difficult to reach firm conclusions about the impact of Cecil's death on policy adoption. We identified three major policy changes that have the potential to impact lion trophy imports in the eight countries we analysed. However, one of these changes, the EU's new permit requirements for lion imports, occurred 4 months prior to Cecil's killing. Additionally, the U.S. policy change represented a final decision on a petition that had been filed 4.5 years earlier, and for which a preliminary recommendation had already been issued. Thus, the influence of Cecil's death, if any, was probably on the timing rather than the substance of the decision. The policy change in France is most attributable to the existence of a post-incident policy window. It occurred c. 4 months after Cecil's death, and the new policy addressed only the import of lion trophies.

Possible reactions by other EU member states may have been muted by the EU's pre-existing policies. In addition to the 2015 policy change requiring the issuance of import permits for lions and several other species, the EU's Scientific Review Group on Trade in Wild Fauna and Flora releases periodic conclusions in which negative opinions are issued, re-evaluated and rescinded regarding the import of specific species/country combinations. As such, the combination of the EU's policy requiring import permits for lions and a country-specific system of evaluating the advisability of allowing imports more generally may have either created a perception by policymakers that no change was needed, or provided sufficient political cover for policymakers to avoid adopting new policy.

In the case of the USA, policy developments before and after Cecil's death suggest that the case spurred a limited number of attempts to change policy. The sponsors of the three federal bills, along with those of the Connecticut and New York bills, all clearly sought to capitalize on a post-incident policy window by incorporating ‘Cecil’ into the bills’ titles. For the remaining bills, a connection to Cecil's death is less clear, as none referenced Cecil explicitly, most contain 10 or more other species, and one (Illinois) does not specify any particular species.

Nevertheless, relevant bills were introduced in the U.S. federal government and in eight states in the post-incident 2015–2016 legislative sessions, compared with only one during the five and a half years preceding Cecil's death. Although a proposed change in nine out of a possible 52 jurisdictions (including the federal and District of Columbia governments) may not indicate the beginning of any broad post-Cecil movement, it certainly suggests that policy advocates perceived a window of opportunity to pursue policy change. However, our review also illustrates just how ‘sticky’ existing policy can be. Out of the nine jurisdictions, only Hawaii and New Jersey adopted new policy.

When we consider the totality of this evidence, the post-incident surge in efforts to change national and subnational policy and the low success rate of those efforts are entirely consistent with scholars’ theories of policy change. Simply put, public attention and the opening of a policy window are often insufficient for policy change to occur across a range of issues, particularly for those that are usually of low salience to the general public. Thus, although Cecil's death may have introduced many people to the issue of trophy hunting of lions, and even caused them to choose a side in the controversy, the Google Trends data do not suggest any enduring increase in public attention to the topic. In the absence of any sustained, heightened public attention, it is not surprising that Cecil's death did not lead to widespread policy changes.

If public interest has receded, we anticipate that both the number of proposed changes and their success rate will drop as policymakers turn their attention elsewhere. The short-lived window created by the immense public attention to the killing of Cecil the Lion seems to have closed.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jani Actman, Jeremy Clare, Daniela Freyer, Mark Jones, Masha Kalinina, Kirin Kennedy, Colman O Criodain, Jeff Patchen and Elly Pepper for their assistance with our research. We also benefitted from conversations with colleagues at the Cecil Summit hosted by WildCru and Panthera at Oxford University during 4–7 September 2016, and thank David Macdonald for inviting us to participate. All research associated with this article was conducted in accordance with all applicable institutional and statutory requirements using pre-existing publicly available data.

Author contributions

SC and DK jointly conceived the research design and wrote the article. SC collected the internet search activity and policy data, which SC and DK analysed collaboratively.

Biographical sketches

Stefan Carpenter’s research interests include environmental law and policy, wildlife policy, community-based wildlife management, and common-pool resource governance. David Konisky’s current research focuses on environmental politics and policy, regulation, and public opinion.