Introduction

Social inclusion of disabled people has emerged as a major management and policy issue in Australia (Gooding, Anderson, & McVilly, Reference Gooding, Anderson and McVilly2017). Currently, one in five Australians are disabled (4.2 million). Although social inclusion is not limited to income/poverty, Australia is the lowest-ranked Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) country for relative income of disabled people with 45% of them near or below the poverty line (OECD average: 22%) (Addis, Michaux, & McCutchan, Reference Addis, Michaux and McCutchan2018). With unemployment higher, poverty more pronounced and poor health and crime higher for disabled people, there is an urgent economic and social need for social inclusion of disabled people in society (Addis, Michaux, & McCutchan, Reference Addis, Michaux and McCutchan2018; Thomas, Gray, McGinty, & Ebringer, Reference Thomas, Gray, McGinty and Ebringer2011). Although national disability policy in Australia supports social inclusion, with some government departments undertaking studies in partnership with arts organisations (DADAA Inc., 2014), it is surprising how little academic and sectoral attention disability in the arts has received. As a ‘means of expression and development’ and with an ‘approach to creative activity that connects artists and local communities’ (Barraket, Reference Barraket2005, p. 3), evidence suggests that arts – encompassing visual, performing and literary arts, ranging from elite to community arts – leads towards social inclusion of individuals (Azmat, Fujimoto, & Rentschler, Reference Azmat, Fujimoto and Rentschler2015; Barraket, Reference Barraket2005). Individual benefits derived from the arts can lead to greater self-esteem, while at the community level the arts can contribute to neighbourhood renewal, create or strengthen communities, develop social capital and promote social inclusion by addressing social challenges, such as health, crime, employment and education in deprived communities (Azmat, Fujimoto, & Rentschler, Reference Azmat, Fujimoto and Rentschler2015). Furthermore, the arts ‘comfort in times of trouble’, heal, inspire community participation and foster a compassionate society (Chew, Reference Chew2009, p. 9). However, social inclusion and its subsequent benefits are beset by barriers which may be unequally distributed and/or unattainable for some disabled people, a topic which has received limited academic attention. Management implications include changes in policy and praxis that entail taking an integrated approach to disabled people focusing on multiple levels (Syed & Kramar, Reference Syed and Kramar2009), as described later in this paper. Within this context, this paper aims to examine barriers to social inclusion of disabled people in the performing arts. For the purpose of the paper, we define disabled people as those with physical, cognitive or intellectual disability.

Although management scholars have examined social inclusion in relation to Indigenous artists (Congreve & Burgess, Reference Congreve and Burgess2017) and disabled people in community organisations (Fujimoto, Rentschler, Le, Edwards, & Härtel, Reference Fujimoto, Rentschler, Le, Edwards and Härtel2014), the management perspective has received less attention with respect to disabled people in the arts. Accordingly, this paper fills this gap in the management literature by examining barriers that disabled people face in relation to their social inclusion in the arts, with regards to four dimensions: access (Gidley, Hampson, & Wheeler, Reference Gidley, Hampson and Wheeler2010; Kawashima, Reference Kawashima2006; Kusayama, Reference Kusayama2005), participation (Evans, Bellon, & Matthews, Reference Evans, Bellon and Matthews2017; Gidley, Hampson, & Wheeler, Reference Gidley, Hampson and Wheeler2010; Kawashima, Reference Kawashima2006; Putnam, Reference Putnam2000), representation (Kawashima, Reference Kawashima2006; Lindelof, Reference Lindelof2015) and empowerment (Evans, Bellon, & Matthews, Reference Evans, Bellon and Matthews2017; Gidley, Hampson, & Wheeler, Reference Gidley, Hampson and Wheeler2010; Themudo, Reference Themudo2009; vom Lehn, Reference vom Lehn2010). We answer the following research question: What are the barriers to social inclusion for disabled people in the arts?

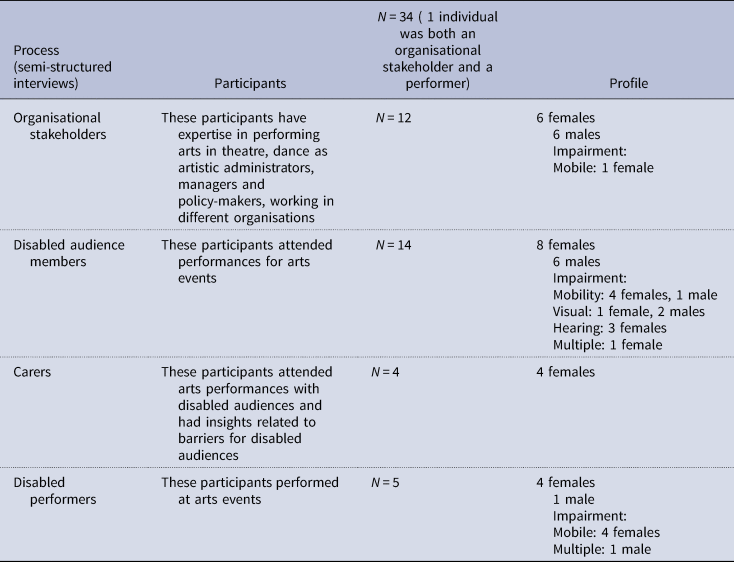

We use a qualitative study of semi-structured interviews to examine the question using the lens of the social model of disability. We interview disabled people who are actively involved in the performing arts, namely disabled audiences, carers, disabled artists in performing arts and people working in performing arts organisations such as artists and administrators as well as advocates, executives and board directors. Such diversity in participants enabled us to examine challenges in social inclusion in the performing arts.

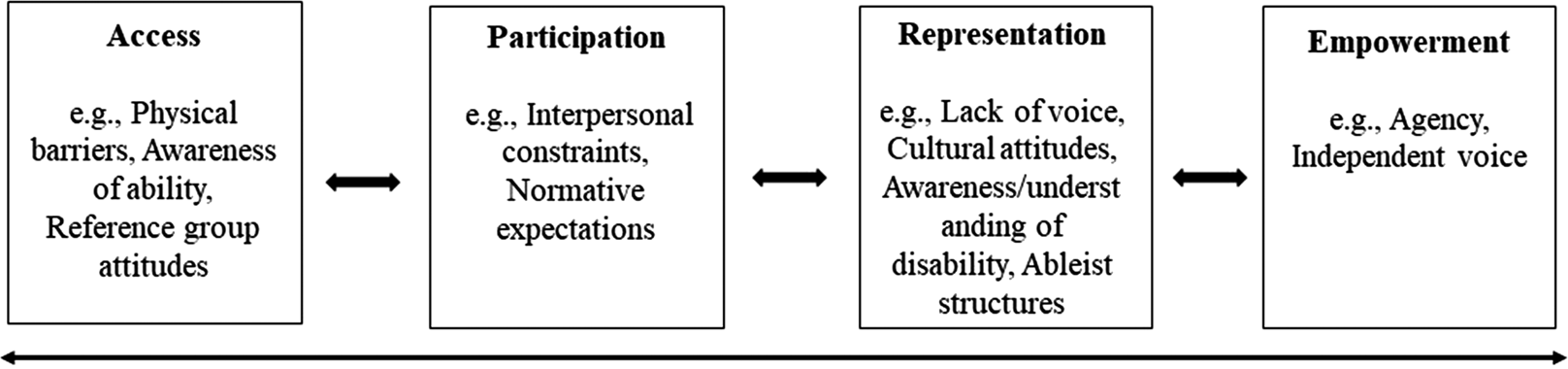

The study contributes towards expanding knowledge about barriers to social inclusion of disabled people in the performing arts by bringing together and analysing four dimensions of social inclusion that have not previously been examined holistically. Furthermore, using the voices of disabled people and other stakeholders, it develops a framework for management to better understand and conceptualise inclusion issues facing disabled people and identify key barriers to their social inclusion, which is timely given the under-researched nature of the topic. The framework (see Figure 1) thus provides a starting point for change leading to workplaces becoming better suited to maximising the inclusion of disabled people and could be applied for inclusion of people from other disadvantaged backgrounds as well as migrants or refugees. The framework also contributes to facilitating academic discussion about social inclusion/exclusion of disabled people and other disadvantaged members in workplaces. Although the framework is developed based on a study in the Australian context, its findings could be generalised to other nations seeking to understand barriers to social inclusion for disabled people as a means of seeking to overcome them.

Fig. 1. Access, participation, representation and empowerment (APRE) framework of barriers to social inclusion.

The rest of this paper is structured in the following way. We start by discussing the social model of disability to provide the theoretical underpinning of our study. Next, we provide insights into different interpretations of social inclusion and its four dimensions (access, participation, representation and empowerment) followed by an examination of how arts can facilitate social inclusion. This is followed by a discussion of our methodology, the findings, the empirical model and the theoretical and managerial implications of the study.

Literature review

Social model of disability

To further understandings of barriers faced by disabled people within the performing arts, this paper draws upon the social model of disability – a model that focuses on societal structures rather than individual impairment (Woods, Reference Woods2017, p. 1094). The social model recognises/makes the crucial difference between impairment and disability (Oliver, Reference Oliver1990). Within this model, impairment is defined ‘in relation to a species norm in terms of functional ability’ (Chapman, Reference Chapman, Rosqvist, Chown and Stenning2020, p. 218) or ‘loss’ in some ability that is assumed to be common to humans with impairments themselves' (Rosqvist, Chown, & Stenning, Reference Rosqvist, Chown and Stenning2020, p. 5). It considers disability to be societal failure, failing to accommodate and accept impaired individuals (Oliver, Reference Oliver1990). People are disabled by ableist structures, both physical and attitudinal (Rosqvist, Chown, & Stenning, Reference Rosqvist, Chown and Stenning2020, p. 5). Rather than an individual issue, the social model emphasises ‘material factors, social relations and power structures that exclude people with a disability’ (Verhaeghe, Van der Bracht, & Van de Putte, Reference Verhaeghe, Van der Bracht and Van de Putte2016, p. 234). As argued by Oliver (Reference Oliver1990, p. 33), this includes:

all the things that impose restrictions on disabled people; ranging from individual prejudice to institutional discrimination, from inaccessible public buildings to unusable transport systems, from segregated education to excluding work arrangements.

The social model, hence, argues for the removal of these barriers and has been accompanied by a social movement designed to politically address the social exclusion of disabled people (Verhaeghe, Van der Bracht, & Van de Putte, Reference Verhaeghe, Van der Bracht and Van de Putte2016, p. 234). Within the social model it is the lived experience that is essential to further understanding and research of the barriers to independence and equality (Rosqvist, Chown, & Stenning, Reference Rosqvist, Chown and Stenning2020, p. 5).

The social model offers a ‘simple, memorable and effective’ idea (Shakespeare, Reference Shakespeare and Davis2006, p. 199). This simplicity makes it easy to explain and presents a ‘clear agenda for social change’ (Shakespeare, Reference Shakespeare and Davis2006, p. 199). However, as noted by Shakespeare (Reference Shakespeare and Davis2006, p. 200), the model's simplicity is also its weakness. For example, a limitation of the social model is that it fails to identify impairment. Shakespeare pointed out that as early as 1992 Crow had argued that disabled people cannot simply pretend that their impairments are irrelevant (cited in Shakespeare, Reference Shakespeare and Davis2006, p. 200). For many disabled people their impairment is an important aspect of their lives and once the term ‘disability’ is located and understood as a form of ‘oppressive social reactions’ placed upon the impaired, ‘there is no need to deny that impairment’ or that ‘in many situations both disability and impairment effects interact to place limits on activity’ (Thomas, Reference Thomas, Barnes and Mercer2004, p. 29).

A second important limitation noted by Shakespeare (Reference Shakespeare and Davis2006, p. 201) is the concept of a ‘barrier-free Utopia’. Put simply, a world in which people with impairments are no longer disabled by barriers is hard to operationalise. For example, the sights and sounds of musical theatre will remain inaccessible for those lacking sight or hearing. Moreover, in some situations, different accommodations are incompatible with different impairments or indeed those with the same impairment may require different solutions (Shakespeare, Reference Shakespeare and Davis2006, p. 201). To highlight this, some individuals impaired by blindness may require Braille while others require large print or audio files (Shakespeare, Reference Shakespeare and Davis2006, p. 201). As such, in some situations, environmental change remains impossible, while in others, feasibility and resource constraints make other arrangements more practical (Shakespeare, Reference Shakespeare and Davis2006, p. 201).

Despite these limitations, services can and should be adapted wherever possible (Shakespeare, Reference Shakespeare and Davis2006, p. 202). The social model thus serves as a ‘practical tool’ rather than theory, idea or concept (Oliver, Reference Oliver, Barnes and Mercer2004, p. 30). From a management perspective, understanding barriers to social inclusion from the social model lens is important as it offers insight into the barriers faced by disabled people at both an organisational and societal level. Embedded in our argument is the premise that for managers to be effective agents for social inclusion they must understand disabled people beyond policy and the individual, by examining how people are disabled by societal factors. As such, this paper, drawing upon disabled stakeholders within the performing arts, offers a social inclusion framework to help further understand organisational and societal issues facing disabled people.

Social inclusion

Social inclusion ensures that everyone in society has opportunities, capabilities and resources to enable them to contribute to and share in the benefits of community or national development (Cultural Minister's Council, 2009). It has been argued that social inclusion can be achieved by taking actions to reach a moral imperative: leave no one behind and avoid the potential economic and social costs of exclusion (Report on the World Social Situation, 2016). Social inclusion is, therefore, seen as the process of providing opportunities to include people from all backgrounds, ensuring that they have the resources, opportunities and capabilities to work, learn, engage and have a voice (Australian Social Inclusion Board, 2012). Similarly, Barack (Reference Barack2010) sees social inclusion as provision of an equal opportunity platform for minority members to participate fully in all socio-economic activities.

Social inclusion and its dimensions

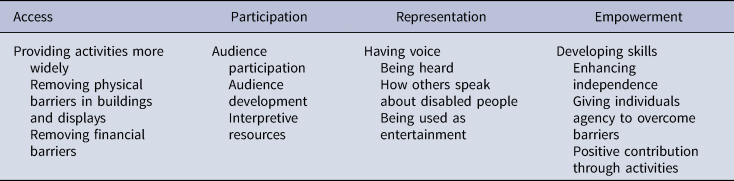

Social inclusion has no single definition, being interpreted in diverse ways. For this paper, we define social inclusion as a process with four interlocking dimensions in which everyone feels valued and has the opportunity to participate, for example, through performances, programmes or events, whether or not they have a disability. These four dimensions have been identified by scholars, but the four of them have not been discussed in a holistic manner, as far as the authors could determine. The next section provides a brief assessment of each dimension and its relationship to the arts. Although we analyse them separately, we recognise that there may be overlap in these dimensions.

Access

Access was first discussed in the UK during the 1970s and 1980s as part of the review of museum policy at the government level. The aim was to open cultural activity to a wider sector of people as audiences, according to Ames (Reference Ames1985), one of the earliest advocates.

In 1998, Sandell expanded this concept to the realm of social inclusion by suggesting that barriers to access of museums ‘be removed by changing, for example, the ambience of the building, signage and the language used in displays’ (Kawashima, Reference Kawashima2006, p. 58). Access continued to be a concept mainly related to museums well into the 21st century. Kawashima (Reference Kawashima2006) discussed progress made over time with an economic focus, accounting for the decision to make museums and galleries free. Thus, financial barriers were eliminated, making museums open to all classes. Taylor and Bogdan (Reference Taylor and Bogdan1989), early proponents of social inclusion for disabled people, said that access can be increased by interaction between those with and without disability. Their focus was the mentally challenged in the USA, while Kusayama was concerned about inclusion for the visually impaired in Japan. He found that accessible facilities for people with mobility difficulties are more advanced compared with those who have sensory difficulties (2005, p. 877). This paper is different in that it represents all disabilities, moves the location from museums to performing arts and deals with disabled people as audiences and performers.

Participation

Participation came a decade later, linking social justice to equitable participation in the arts (e.g., Putnam, Reference Putnam2000), often in museums (e.g., Sandell, Reference Sandell1998, Reference Sandell2003). It took until the early part of the 21st century for the ways audiences participate in the arts to be examined. Scholars have investigated participation from various perspectives (e.g., Rentschler & Hede, Reference Rentschler and Hede2007; Sharma & Varma, Reference Sharma and Varma2008; vom Lehn, Reference vom Lehn2010; Walmsley, Reference Walmsley2016). Gidley, Hampson, and Wheeler (Reference Gidley, Hampson and Wheeler2010) consider participation to be the next step in social inclusion since it has a broader interpretation than access. They focused on the participation of Indigenous peoples and refugees (as well as disabled people) in sport, education and the arts, with social justice the ultimate aim. Lindelof (Reference Lindelof2015) was interested in not only why reaching broader audiences is important, but also how to find ways to reach them. However, the issue has rarely been examined from the perspective of disabled people themselves. Although a few studies on social inclusion of disabled people have been conducted in different countries with different research approaches (Fujimoto et al., Reference Fujimoto, Rentschler, Le, Edwards and Härtel2014; Ruiz, Pajares, Utray, & Moreno, Reference Ruiz, Pajares, Utray and Moreno2011; vom Lehn, Reference vom Lehn2010), museums were generally the focus. One study on the participation of visually impaired visitors to museums (vom Lehn, Reference vom Lehn2010) concluded that interpretive resources such as labels, tangible objects and guides are insufficient to enable social inclusion in museums. Taken together, studies on participation suggest a need for a deeper examination of the methodological and theoretical foundations of social inclusion. This paper attempts to broaden the understanding of the issue by looking at it from the perspective of the very people who may feel excluded.

Representation

Representation has been a more recent development that links scholarly research in human dignity, potential and complexity to being recognised and included in society. Representation is defined as who does the speaking and how people are spoken of (Bacchi, Reference Bacchi2009). Accordingly, representation is defined in two ways as: (i) the voice in discussion and decision-making, whether that's as an employee working in the arts or as a consumer of the arts (e.g., artists, managers and board director); and (ii) how disabled people are spoken about by others (Rentschler, Lee, Yoon, & Collins, Reference Rentschler, Lee, Yoon, Collins, Wyszomirski and Changin press).

Regarding the former, including the voice of disabled people provides richness and depth to human capabilities and social contribution (Kuppers, Reference Kuppers2005; Lindelof, Reference Lindelof2015). Despite the need for representation for social inclusion, the voice of disabled people is absent from education, employment, community, arts and cultural accounts, including reflections on human rights for disabled people and representation of human dignity (Allan, Reference Allan and Tremain2005).

Regarding how people are spoken of, categories of knowledge, of which people are particularly important, often form the ‘truth’ of a subject and affect the way people think of themselves and others (Bacchi, Reference Bacchi2009). Historically, representation of disability has been that of disposal or ridicule. Disabled people have long been used for entertainment purposes and dramatisation of what it means to be disabled (Bailey, Reference Bailey and Bell2011; Richardson, Reference Richardson2016). According to an article published by the Anti-Defamation League in 2005, disabled children were thrown under horses' hooves at the Coliseum, the ‘ship of fools’ which after sailing from port-to-port for public ridicule would abandon disabled people at the end of the tour and use disabled people in circuses and exhibitions for public humiliation. The infamous Bedlam mental asylum was one of ‘London's favourite tourist spots, people entered the “Penny gates”, roamed the yards and were “entertained or shocked according to their personal taste”’ (Scheerenberger, Reference Scheerenberger1983, p. 44). Although such practices are no longer socially acceptable, forms of entertainment such as cinema, offered a ‘safe, politically correct and ethically permissible forum for our curiosity’ (Conn & Bhugra, Reference Conn and Bhugra2012, p. 55). As such, the inclusion of disabled people as both artists and audiences goes beyond mere access and participation. For example, supporting disabled artists not only ‘improves the welfare of a minority group’, ‘it also allows disabled people as a whole to form a positive identity, not a tragic one, and helps re-conceptualise disability’ (Bang & Kim, Reference Bang and Kim2015, p. 552) through representation.

Empowerment

This is also a more recent notion. Empowerment has been examined conceptually, calling for more research in this dimension (Themudo, Reference Themudo2009). More recently, empowerment has been examined in terms of museums (Malt, Reference Malt2005) and in the non-profit context (Themudo, Reference Themudo2009), and at the individual, organisational and community levels (Zimmerman, Reference Zimmerman2000). At the individual level, the focus of our study, empowerment can assist in developing skills that enhance independence (Zimmerman, Reference Zimmerman2000). Empowerment can also be related to the social model of disability. Although disability is often viewed as a medical or individual problem (that which pathologises the individual as disabled and in need of medical intervention, treatment and, possibly, cure) (Clarke & Van Amerom, Reference Clarke and Van Amerom2008), the social model of disability is seen to provide individuals with the agency to overcome barriers to access, participation and representation. Empowerment enables people, especially those with disability, to move beyond seeing their engagement as therapy to a higher level where they negotiate a dignified, equitable and independent life. Hence, people can contribute to life in a positive manner through activities, including the arts (Evans, Bellon, & Matthews, Reference Evans, Bellon and Matthews2017). Yet, despite empowerment, segregation exists, which can be disempowering, creating barriers to inclusion. Hence, there is a need to review how the lives of disabled people are positioned vis-a-vis others in society, Table 1 summarises these four dimensions of social inclusion as identified in the literature: access, participation, representation and empowerment.

Table 1. Four dimensions of social inclusion

Social inclusion of disabled people in the arts

The arts are generally seen as a tool to engage people emotionally, bridging barriers and providing social experiences that have spill over effects at the individual, group, organisational and community levels, thus facilitating social inclusion (Azmat, Fujimoto, & Rentschler, Reference Azmat, Fujimoto and Rentschler2015; Chew, Reference Chew2009). Recently, the universal relevance of disability presaged a new agenda in arts and cultural education (Bolt & Penketh, Reference Bolt and Penketh2016). They quoted Mitchell and Snyder as saying the ‘disabled body’ emerged as a ‘potent symbolic site of literacy investment’ (2016, p. 1).

Despite the potential of the arts to include people from all backgrounds, those benefiting from the arts still tend to be predominantly white, middle-class and privileged as has been mentioned by numerous scholars (e.g., Create London., 2018; Rankin, Reference Rankin2018). Authors (Azmat, Fujimoto, & Rentschler, Reference Azmat, Fujimoto and Rentschler2015; Gidley, Hampson, & Wheeler, Reference Gidley, Hampson and Wheeler2010; Kawashima, Reference Kawashima2006; Kusayama, Reference Kusayama2005; Lindelof, Reference Lindelof2015) argue that diversity is under-represented in the arts, pointing out that those on the board, executives, staff and volunteers, and even those in the audience are mainly from the same narrow socio-economic group. This tends to reinforce social inequality, making it hard for ‘the other’ to gain entry to the arts industry, due to its gatekeepers, thus providing management with additional challenges for implementing inclusion. Although there is some focus in voluntary, non-profit institutions on the delivery of services for disabled people, there has been less interest in understanding the role of arts and disability. Furthermore, although national arts agencies and departments (Cultural Minister's Council, 2009; Hutchinson, Reference Hutchinson2005) have produced policies and strategies for disabled people, research on arts and disability remains sparse. In addition, from a total budget of over $200 m, the Australia Council allocated only $1.3 m to arts and disability in 2018 (Rankin, Reference Rankin2018). To put this in perspective and illustrate the low priority given to it, while 20% of Australians live with a disability, only 2.3% of the Australia Council's budget is allocated to this sector. Despite the acknowledgement that the benefits of participating in arts extend beyond aesthetic norms, limited effort has been made to allow disabled people to interact with others and develop relationships where their disability is not seen as exceptional, which helps them feel included (Chew, Reference Chew2009; Wiesel & Bigby, Reference Wiesel and Bigby2016).

Disabled people in the arts are becoming more vocal about social inclusion, demanding it or being prepared to protest at exclusion, within the framework of Australian social policy. The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) was introduced in 2013 as a federal government policy reform, and as a means of empowering disabled people by providing them with certainty of support (Addis, Michaux, & McCutchan, Reference Addis, Michaux and McCutchan2018). It oversees social inclusion for individuals but also more generally established a network of supports for disabled people (Bonyhady, Reference Bonyhady2014; Ryan & Collins, Reference Ryan and Collins2008). At the same time, institutional reforms were undertaken which increased the size and importance of the voluntary sector for service delivery. Many of the arts organisations, where these changes took place, fall into the category of voluntary, independent, non-profit or government organisations. Such changes were accompanied by growing public awareness for and support of social inclusion for disabled people a shift in the role that arts organisations and their management play in communities regarding access, participation, representation and empowerment (Cultural Minister's Council, 2009; Gooding, Anderson, & McVilly, Reference Gooding, Anderson and McVilly2017).

Method

We undertook a qualitative study to explore social inclusion of disabled people in performing arts through personal testimonies. The voices of disabled people are foregrounded, along with other stakeholders (Allan, Reference Allan and Tremain2005). The relevance of employing qualitative enquiry while studying social phenomena has been emphasised by several authors (Bogdan & Biklen, Reference Bogdan and Biklen1992; Naraine & Lindsay, Reference Naraine and Lindsay2011) to capture richer participant experiences and gain understanding of their unique personal and social experiences in an area that is largely unexplored (Glesne & Peshkin, Reference Glesne and Peshkin1992; Stake, Reference Stake1995). Similarly, our study aimed to gather information regarding the personal experiences of people with and without disability in order to foreground their views.

Data collection

Our study included 34 semi-structured interviews with participants: (i) disabled audiences (n = 14); (ii) carers (n = 4); (iii) disabled performers (n = 4) and (iv) stakeholders such as staff, fundraiser/developer, managers, artistic manager, former and current board directors with and without disability involved in performing arts organisations (n = 12). Table 2 shows the data sources, their insights in the study and some demographic characteristics such as gender and types of disability (as being mobility, hearing impairment, visual impairment and multiple impairments) for the participants. Our stakeholder interviewees were drawn from arts organisations on a publicly available list on the website of Arts Access Australia, identifying arts organisations which engage with disabled people. We obtained approval from four arts organisations to interview their staff, performers with disability and board members. Interviewees were purposively selected from amongst those who engaged with disabled people across different roles, and were sourced, using the snowball sampling technique. For example, we asked friends and colleagues for recommendations for participants with disabilities (Merriam, Reference Merriam1990) thus starting with individuals who had the desired characteristics and used their connections to recruit other participants with shared characteristics for our study (Sadler, Lee, Lim, & Fullerton, Reference Sadler, Lee, Lim and Fullerton2010). Participants in the study were asked to share research information with other participants they knew who might be eligible for the study. Participation in the study was voluntary and each participant's disability was taken into consideration when conducting the interviews so as to ensure a safe environment.

Table 2. Data sources and participants

For each of the four participant groups, a semi-structured interview guide was prepared in order to explore and compare their experiences regarding social inclusion. However, the primary objective was to encourage participants to lead the conversation in a way that was important to them when recounting their inclusion experiences (McGrath, Palmgren, & Liljedahl, Reference McGrath, Palmgren and Liljedahl2019). A semi-structured interview guide started with brief demographic background information relevant to the study (e.g., career history; education; ability or disability; gender and age) and followed by warm-up questions to build rapport (Bell, Reference Bell2014; Schoultz, Säljö, & Wyndhamn, Reference Schoultz, Säljö and Wyndhamn2001) such as: ‘How often do you go to programs offered by performing arts organizations?’, ‘How do you obtain needed information?’, ‘Do you go to events by yourself or with a carer?’ If they answered ‘with a carer’, an additional interview was conducted with the carer, with their consent. The main interview questions regarding social inclusion of disabled people emerged from related literature, including Bang and Kim (Reference Bang and Kim2015); Bolt and Penketh (Reference Bolt and Penketh2016); Naraine and Lindsay (Reference Naraine and Lindsay2011); Lindelof (Reference Lindelof2015) and Woods (Reference Woods2017). Some of the questions asked were: ‘Was it easy for you to be an audience member at performing arts programs? Why/why not? Please give examples’. ‘Did you feel included? If not, why not? Please give examples’. ‘What were some of the challenges experienced from being a disabled audience member at those programs? Please give examples’. Most questions were followed-up to elicit details about their experiences.

As for stakeholders, questions such as ‘What are the barriers/issues from your organisation's perspective with regard to social inclusion for disabled people?’ and ‘What do you think are the ongoing challenges for social inclusion for the future of your organization?’ Finally, for disabled performers, questions such as: ‘What recommendations can you provide to arts program stakeholders as an active performer with physical disability (e.g., mobile disability, visually impaired, hearing impaired)? Please give examples’. Thus, the aim was to obtain their views regarding the scenario and elicit suggestions for improvement.

The interviews lasted around 40–50 min, were digitally recorded and transcribed. We interviewed until data saturation was achieved. Data saturation was reached with 10 respondents in each group with the exception of carers and disabled performers.

This study was undertaken in line with university research ethics committee requirements. We recognise the limitations of the methodology by using an interpretive approach which generalises to theory rather than to a population or sample. We recognise the limitations of using an interpretive approach.

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed and were first read in full and coded manually into themes. We took a holistic approach to concept development, devising first-order and second-order analysis by coding themes, following a two-stage approach in analysing data (Williams & Murray, Reference Williams and Murray2015). First-level coding followed a thematic approach. Second-order coding took themes from the first-order coding, using the four dimensions of social inclusion as a framework for analysis (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). The use of researcher and researched voices enabled links between data and induction of new concepts, confirming the rigour of concept development and theory building (Williams & Murray, Reference Williams and Murray2015). Having multiple authors enabled the data analysis stage to be thorough and trustworthy by clarifying points such as the meaning of quotes, by building on identified themes.

Findings

This section discusses themes arising from interviews with representative quotes from the respondents (using pseudonyms) as evidence.

Barriers to social inclusion

Evidence collected from the interviews identified numerous barriers to inclusion. The issues identified fit within the four tenets of social inclusion – access, participation, representation and empowerment. This section identifies those barriers and extends them via evaluation of other barriers to inclusion.

Barriers to access

Barriers to access included elements such as physical barriers, uncertainty, lack of awareness and reference group attitudes. Although physical needs of disability, in comparison with cognitive, are more recognised, understood and addressed, physical barriers remained a central reason disabled people were unable to access a performance/event. Physical barriers were encountered before arriving at the event. For example, car parking was an issue regarding the number of suitable car parks, size of allocated parks and their location. Once at the event, further physical barriers were encountered: Matt, an audience member with a mobility disability shared his insights about seating:

It is difficult because the seats are narrow. You don't have much legroom [There is] no back support [for] the seats. It is an old theatre [with] stairs. … [It] was designed in an age where disabled people were not out and about (Matt).

As evident in Matt's example, recognition that physical barriers exist is attributed to previously held views of disability. Although it should be acknowledged that some buildings are limited by issues such as heritage listing, and or space, awareness of barriers such as those highlighted by Matt need to considered. If the barrier cannot be eliminated, an alternative can be implemented. This is an issue we explore further when discussing participation.

There were also institutional barriers, such as steps into venues. For example, Bertie, a blind audience member said: ‘steps are everywhere. Poles are always my greatest fear’. Furthermore, a female audience member with a physical disability supported this view, stating that steps caused her ‘to make phone calls and enquiries to make sure you can get to your seat’ (Ellen). In other words, findings suggest insufficient thought has been given to building design or interior design for all people, creating barriers to inclusion, which aligns with the tenets of social model of disability.

Findings further suggest that physical barriers also create issues during the performance. For example, the physical challenges associated with intermission combined with theatre policy mean that some disabled audience members go without basic needs, such as water:

it takes me so much longer to get down the stairs to go to the bathroom or to grab a drink in intermission … [So] I go without (Matt).

In addition to not being able to satisfy basic needs such as access to water, the inability to participate in intermission limits potential social interaction with other audience members. As such, barriers that limit access also limit the ability of disabled attendees to extend their social networks, be seen by others as participating members, decode interpretations of art through interpersonal interactions and expose non-disabled counterparts to their views of the event.

Barriers to inclusion also included reference group attitudes. Reference group attitudes influence the availability and opportunity to access activities and can include attitudes regarding the appropriateness of the activity (Crawford & Godbey, Reference Crawford and Godbey1987). A common reference group attitude was found to be age (i.e., age restrictions). Although some programmes had positive impacts, age restrictions often meant that once disabled people reached a certain age, they were no longer eligible to be part of the programme. For example, Raylene shared her view of the limitations of participation in disability theatre, ‘the bit that's sad about it …. is that it [participation in disability theatre] stops at 27. It's a great drawback’.

Others with invisible disabilities (or their carers) considered access needs were not properly understood, feeling more like ‘box ticking’ than inclusion. For example, one carer, Heide, told us that her son ‘could not see’ as he was ‘way up the back’ in the theatre. As she advised, there was no awareness of how to accommodate him, going so far as to say that ‘the toilets were also not accessible’ or ‘not unisex’ thus preventing carers from the opposite sex providing needed assistance. Simple solutions can include signage in ‘braille’ or a ‘tactile map’ or ‘audio descriptions’ of where toilets or amenities are located, as one blind audience member, Kerry, advised. Along this line, disabled performers discussed how transparency in the sector would allow them to communicate their access needs:

I'd like to see the sector change so that there's better access: those who identify as disabled artists (should) be able to book without being penalized (Amy).

Access was not only an issue for artists with disability. Customers were also entitled to it. Although safety is an essential customer right, disabled audience members spoke of concerns regarding their physical safety:

I would be concerned if there were an emergency because I would not have somebody to assist me. … I never go by myself because of access (Matt).

In other words, human safety is a concern as well as convenience and comfort. Therefore, arts venues require special signposting for the benefit of disabled people or designated helpers to aid disabled people in the case of an emergency. Moreover, extra effort should be made to ensure that disabled people are aware that these measures are in place so that they feel more comfortable about attending performances at the venues.

In sum, barriers to access entailed structural barriers (e.g., parking, seating and signage), which can be explained by the social model in that they are produced and designed by society with little awareness of the needs of disabled people. Although the barriers identified were numerous, it should be noted that this is a limitation of the social model – not all disabled people will face the same barriers – so at times solutions for one may be incompatible with another. Although this limitation can sometimes provide complex or insurmountable challenges, it should not result in a dismissive approach nor prevent management (or other stakeholders) from eliminating, attempting to reduce or mitigating access barriers.

Barriers to participation

As with access, barriers to participation emerged as a theme for all stakeholders. What was evident within themes relating to participation was just how distinct (and important) a category was when compared to access. For example, representation, exposure and understanding of disability impacted how disabled people who had access could participate in artistic performances. Although participation was not denied, even accommodated, the way in which it was done was often viewed by the provider as a nuisance.

Although access was sometimes available, participation was dependent on the assistance of staff and/or a ‘carer’. When assistance was needed to negotiate barriers in-place, disabled audience members were often made to feel as though their presence was a burden. For example, as stated by Holly, an audience member with a physical disability: ‘The person who had to open a special door behaved like it was a hassle’. Such attitudes limit the inclusion of disabled people and reflect the values of neoliberalism and capitalism – a society that values independence and achievement (Oliver, Reference Oliver1990). These dimensions are seen to empower individuals but ignore complex social relations and structures within a society dominated by able-bodied mindsets and assumptions. Thus, approaches to independence are problematic, and gaining acceptance (or understanding) is difficult in a climate where ‘stigma may be exacerbated by heightened public stinginess toward those deemed unproductive or burdensome’ (Blum, Reference Blum2007, p. 203).

Extending feelings of being a ‘hassle’, an important issue concerning the participation of disabled audience members was their treatment as second-class citizens. The following quote from Louise, an audience member with a physical disability explains that lack of respect can be a barrier as disabled people are ignored, being treated as if they were invisible:

[There can be] a lack of respect because you have a disability. People have patterns of thinking. For example, I go to a ticket counter and ask a question. If someone is there with me, the person behind the counter won't answer directly to me … There is a need for awareness and training for staff.

Although an indirect barrier to inclusion, the passive avoidance of speaking directly to a disabled attendee highlights a prominent issue regarding the participation of disabled audience members. A more active form of avoidance created a barrier due to misunderstandings, identified by Bertie who stated:

People who work on the door always think I'm drunk, because I'm not looking at them directly or I'm struggling to find my way up the steps … it happens a lot.

Such misguided perceptions of barriers to participation were troubling, indeed upsetting for the disabled people we interviewed, limiting their experience at the arts event.

The continuing stereotypical images of disabled people and dominant culture of those without disabilities contribute to misunderstanding and fear of disabled people as well as the underlying notion that disabled people are considered second-class citizens. This can be summed up in the comment: ‘the more difficult one, of course, is getting past people's prejudices and fears’. Extending this view, one disabled person explained: ‘people should be more aware that there are disabled people out there and that… it's more than disabilities you can see, it is also disabilities you can't see’ (Matt). In other words, barriers are not only overt and visible, but also covert and invisible, highlighting the complexity in removing them, as they entail not only physical things but also attitudes that people hold.

Participation was also inhibited by normative expectations of time and work. As argued by Sen (Reference Sen1985), inclusion is often dependent on an individual's ability to function in a manner deemed valuable to the economy. For disabled artists in our study, it was often not that they couldn't do the task, it was when and how the task was expected to be performed that inhibited them:

If you can't start at 9 o'clock in the morning you are penalized (Moses).

Furthermore, for disabled artists, the ability to access opportunities was often circular. For example, the ability to be included was dependent upon their ability to fund their art; but their ability to fund their art was dependent upon being able to participate within a normative structure.

Access to work and other opportunities was dependent on the ability to meet normative standards which pertain to ‘restriction of access to opportunities and limitations of capabilities required to capitalize on the[m]’ (Hayes, Gray, & Edwards, Reference Hayes, Gray and Edwards2008, p. 9).

For example,

… you end up not taking opportunities because you have to financially back yourself. Take Melbourne. I booked eight nights' accommodation for two shows … An able-bodied person would be there for two days … You can't do your festival circuit like everyone else, you don't make money like everyone else (Amy).

In sum, barriers to participation entailed attitudinal barriers that include: ignorance, prejudice and simple lack of knowledge about what to do to create a more inclusive environment for disabled people. This indicates that much remains to be done to enable more disabled people to participate in art activities. Even more so than numbers, it is the quality of participation that needs to be addressed in the effort to improve the health and well-being of disabled people.

Barriers to representation

Representation of categories such as disability have real effects on society (Bacchi, Reference Bacchi2009). Cultural attitudes towards disability are part of a disabling environment that imposes social barriers beyond any individual impairment (Barnes & Sheldon, Reference Barnes and Sheldon2010; Oliver, Reference Oliver1990). In addition to cultural attitudes, the absence of voice was also a barrier to inclusion. Recognising this, we now highlight key inclusion barriers associated with representation.

Both disabled audience members and performers discussed a lack of awareness amongst staff about the different types of disability and capabilities and the way to handle them which impacted their representation:

So many people don't feel capable of saying that in an able-bodied community because then you're the difficult one … You're the princess (Amy).

The lack of voice, or feelings about how their voice would be interpreted imposed both intrapersonal and interpersonal barriers upon disabled stakeholders. In short, disabled people, as in this quote, expressed the view that they are often viewed as inadequate or a burden on society. This is reflective of assumptions embedded within a neoliberal culture and a further example of tension, or conflict, that arises when structure is ignored (or assumed) and individual responsibility paramount. Disabled people may not ‘obey’ the inherent social norms of society and their impairment is often viewed with pity and/or disgust (Park et al., Reference Park2003). A desire to change such perceptions was evident from a disabled artistic director:

Living with an impairment is not a tragedy, it's not something to feel sorry for, we don't want pity, rather envisage performers as professional dancers (Mary).

The point about the importance of the artist being more important than the disability was made repeatedly by performers, arts managers and artistic directors. There is a growing view by disabled people in the arts that they are capable, strong, professional and pursuing a career, rather than undertaking therapy, as was once the dominant view (Solvang, Reference Solvang2018). Nonetheless, despite the potential for arts programmes to benefit disabled people and instigate social change in the wider community, arts programmes for disabled people are still not ‘taken seriously in terms of their artistic outputs and merits’ (Darcy, Maxwell, Grabowski, & Onyx, Reference Darcy, Maxwell, Grabowski and Onyx2019, p. 1). Attitudes to work by disabled artists were evident in our interviews with performing artists, particularly when they did not want to be known as disabled artists. For example, in an interview with Moses, the issue of the seriousness of his work as an artist was important:

… often people won't take work that's coming from a disabled artist as seriously as work that's coming from an able-bodied artist. I let things stand on their merits … I was a non-disabled artist for a long time before I became disabled.

In other words, the complexity of artistry for disabled people is exemplified in this quote. Feelings about barriers to disabled people participating in the performing arts were not limited to the individuals themselves. For example, in our interview with Amy, a disabled artist, spoke of how ableist structures influence the experiences of disabled people at elite cultural events such as awards nights:

An incident happened where the actress winning the award was called to collect it. Then they realized, oh, she can't get up on stage. She had to come onto the stage from backstage. She didn't have the grand entrance like everyone else. She was an outcast. They should've thought about that. They knew she was up for an award. She's clearly disabled. She had a good chance of winning. The argument was that the people that built the theatre wouldn't have thought about that (Amy).

The needs of disabled people and their voices were overlooked in event planning. Consequently, past mistakes are repeated and used as an excuse for present shortcomings. In sum, barriers to representation entailed how disabled people are spoken about and thought of (e.g., negative notions, ideas and concepts), which tends to reinforce the social model produced by the enabled majority. Second, representation is not just how disabled people are spoken of, but who does the speaking. In order to expand representation of disabled people it is imperative that the mindset and outlook of society, in general, be changed regarding awareness of the difficulties faced by disabled people. This can, in part, be achieved by increasing the voice of disabled people and their representation amongst key decision-makers. The findings suggest there is still a long way to go to ensure that representation creates inclusion for all.

Barriers to empowerment

As discussed earlier, the four tenets of social inclusion are intertwined. For example, barriers to access created barriers to empowerment. As identified by participants such as Muge, a staff member in the disability sector, the performing arts bring with them the ability to foster independence through methods such as increasing physical capabilities, education and training. Although the focus of art and disability has been to position the practice of art as one of therapy and/or leisure (Bullock, Mahon, & Killingsworth, Reference Bullock, Mahon and Killingsworth2010; Solvang, Reference Solvang2018), limiting art to its therapeutic value, restricts what the practice can offer. As stated by Brian who is the disabled manager of an advocacy organisation for arts and disability:

Disability arts has come from a place of therapy where the modus operandi is to ‘keep them busy; give them something to do.’ I don't want to disparage that there's therapeutic value. But it's more than that: how can we create an environment that supports disabled artists to flourish and grow?

All stakeholder groups talked about awareness-building of staff to enable them to adapt to disabled people, as a means of over-coming barriers, thus empowering them. For example, ‘there should be respect and inclusion in greeting and placement of people in advance’ (Louise). Such views were not limited to introductions but also considered important in building the whole arts experience. A blind audience member said:

In training, it is not just what can happen in the physical environment but getting people to think about their attitudes and understand that disabled people have a lot to offer as audiences (Bertie).

In short, this quote and the one by Brian, demonstrate that their art, rather than their disability, is an intrinsic aspect of their identity, developed through performance. Further evidence for the importance of empowering the voice of disabled people was that disabled people often found it difficult to voice their own needs:

It's difficult to voice my access needs. That's something I have to work on. But there are barriers. That's why artists who identify as disabled stick together (Amy).

Our findings suggest that disabled people are a market segment that is overlooked or ignored. The need for awareness, respect and change in attitudes in overcoming barriers for disabled people is reinforced by a disabled performer, Eve, stating that ‘people with disabilities need not be feared. They have the capability to bring funds to your organization if only you will ask them and provide them the means to attend your programs’. This is a powerful statement which reinforces the importance of removing barriers to empowerment, so that disabled people can contribute to arts organisations more fully.

In our findings, barriers to empowerment entailed how disabled people are given agency for their actions (e.g., development, training, paid work and even recognition). Disabled people want to have the same rights and opportunities as their able counterparts. When considering disabled artists, while it should be acknowledged that for some disabled people their impairment is part of their identity, a limitation of the social model, for the artists in our study, they want to be recognised as artists (who just happen to have an impairment), not as disabled artists. Identity for disabled people, and how it links to barriers such as empowerment and representation is a complex matter that needs further research.

Bringing together the findings

In response to our research question – what are the barriers to social inclusion for disabled people in the performing arts – our findings have led to the development of an empirical framework. We call it the APER (Access–Participation–Empowerment–Representation) framework (Figure 1) for management of key barriers to social inclusion. As can be seen by the examples provided in Figure 1, barriers related to each aspect of social inclusion were viewed through the social model of disability: societal barriers that require change.

We found that the barriers for social inclusion within the arts occur across the four dimensions – access, participation, representation and empowerment – which are interdependent and intertwined. For example, barriers to access, such as not being able to access certain events or areas, impact participation. Barriers to participation, such as normative expectations, restrict how and when artists with a disability can showcase their work, thus impacting how they are represented. Moreover, in addition to access impacting participation and participation impacting representation, we argue that the model works both ways. For example, the representation of disabled people in the arts impacts participation – such as how cultural attitudes influence interpersonal experiences (e.g., not being spoken to directly).

We placed empowerment at the end of the framework as empowerment ‘seeks to maximise the potential of each human being’ (Gidley, Hampson, & Wheeler, Reference Gidley, Hampson and Wheeler2010, p. 4). As with the other dimensions, we argue that while access, participation and representation influence empowerment, the reverse can also be true. By removing the earlier barriers, a person's pathway is enhanced. When a person's pathway is enhanced their motivation to pursue their goals increases (Egan, Butcher, & Ralph, Reference Egan, Butcher and Ralph2008, p. 35). If more disabled people are empowered to engage in the performing arts (whether as staff, performers or audience members) it increases their representation and a form of representation is self-generated.

Discussion

Despite the emerging focus on including disabled people as is evidenced in the NDIS and other policies, the potential for the arts to include disabled people through the removal of barriers remains somewhat underexplored. Within this context, this study examined the barriers to social inclusion for disabled people in the arts drawing on the responses of multiple stakeholders including disabled people as audiences and performers through the lens of the social model of disability. The strengths of this paper lie in the fact that it includes views of disabled people who are most affected by the barriers, thus shedding light on the efficacy of policies and processes that currently are in place and the barriers faced. Our paper shifts the focus away from museums to performing arts for the social inclusion of disabled people.

Although empowerment is the end goal, each dimension is important. For example, despite barriers regarding access being the most easily recognised and addressed, access barriers remain. Some access barriers can be alleviated through greater funding (Rankin, Reference Rankin2018); however, a shift in attitude is required to make distribution of funding more equitable. Although access occurred in some situations, access alone did not result in social inclusion.

Moreover, we found that barriers to participation put limits on the positive impacts of access, such as a sense of belonging, human dignity and potential future involvement of disabled people. Attitudes towards and understanding of disability were evident concerning participation. The circular nature of participation was prescriptive and descriptive of understandings of disability. By this we mean that how disabled people were invited to participate reflected understandings of disability and prescribed how they were perceived (and treated). The prescriptive and descriptive findings of participation highlight connections between each of the barriers to inclusion.

Barriers associated with representation were linked to dominant discourses in the arts and its associations with therapy. Although not ignoring the arts' therapeutic potential, it limits the potential social inclusion in the arts can offer management in organisations, as our findings indicate. Moreover, if representation of disabled people within the arts is limited to the restoration of disabled people with the aim of creating a person who participates within a normative structure, or something that must be accommodated in order to be politically correct, it restricts how disabled people are perceived and perceive themselves. Each barrier to inclusion (access, participation and representation) impacted empowerment. Lack of voice and desire to limit interactions to those who were members of the disabled community were examples of this. Negative attitudes as well as the lack of respect faced by disabled people emerged in disabled people, audience and performer accounts. Such a finding stresses the need for management change that other organisations can take up, to ensure full inclusion of disabled people. Future research needs to address ways to overcome barriers that relate to the four-dimensional approach to social inclusion identified in this paper (Kawashima, Reference Kawashima2006; Lindelof, Reference Lindelof2015; Themudo, Reference Themudo2009).

Although bringing together our findings led to the development of the barriers to inclusion framework, we recognise the limitations of our study. First, we understand a qualitative study cannot be generalised. However, we have generalised to theory, making advances in understanding disability and society in the arts ecology. A second limitation is the study breadth, which included a number of different types of stakeholders (and thus potentially also its limitations). As noted by Camarero, Garrido, and Hernández (Reference Camarero, Garrido and Hernández2020), the missions of arts organisations are socially focused, with objectives that are both social and economic. As a result, their stakeholder lists are long and complex. Therefore, additional research could be undertaken to develop the framework further, through studies that consider stakeholders separately: in particular, disabled audience members and/or consumers, disabled artists and performers, as well as the awareness, understanding and attitudes of managers regarding the inclusion of disabled people.

Finally, ıt should be recognised that the model being embedded within the social model is itself a limitation, in particular, the idea of a ‘barrier-free Utopia’ (Shakespeare, Reference Shakespeare and Davis2006, p. 201). Although not all barriers to inclusion can be removed and limitations such as differing and sometimes incompatible accommodations still remain, the framework presented offers clear and segmented starting points regarding managerial change, or, as identified below, a tool that can be used to achieve wider organisational goals.

Implications for management

As all the barriers that emerged in our findings relate to the social model of disability, implications for management are profound, necessitating change in policy and praxis. The implications for management entail undertaking an integrated approach to include disabled people focusing on multiple levels as opposed to a fragmented single level focus (Syed & Kramar, Reference Syed and Kramar2009). At the micro-level managers need to engage disabled people in the development and updating of policies and procedures and listen to their voices to not only include them in workforce, but also to facilitate their access, participation, representation and empowerment in workplaces. Including disabled people in the management of art ventures would ensure their participation in decision-making and also empower them, which is central to the social model. Although these policies, processes and procedures are not new for management, enacting them does seem to be new and they are much needed in relation to disabled people.

At the meso-organisational level, managers could focus on raising staff awareness of the needs of disabled people, training and development of staff in understanding disabled people and making necessary changes to remove the barriers. As shown in Figure 1, these matters create an inclusive workplace. Finally, at the macro-level, there is also scope for managers to influence and work with government and other policy-makers on the inclusion of disabled people. Such an integrated approach has implications for managers to understand them beyond policy and the individual, by examining how people are disabled by societal factors through focus on meso and macro levels.

Furthermore, different types of barriers, and how they are interrelated may assist management in achieving wider organisational, and or societal, goals, for example, the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). As argued by Dalton (Reference Dalton2020), the complexity of the SDGs may impede small to medium enterprises from engaging with this framework. Simpler tools, such as the barriers to inclusion framework presented in this paper, may assist management with areas they need to address. An example is Dalton (Reference Dalton2020) and her examination of Sydney Theatre Company. Although the UN SDG 8.5 articulates that:

By 2030, achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value

as Dalton (Reference Dalton2020) finds, current meso-organisational measures may not capture information around disabled people. Accordingly, in the sector, there may be a disconnect between macro-organisational policy, and despite the best organisational intentions, the micro-level outcomes and opportunities for disabled people at the meso-organisational level.

Finally, at the macro-level there is also scope for managers to influence and work with government and other policy makers on the inclusion of disabled people. Such an integrated approach has implications for managers to understand disability beyond policy and the individual, by examining how people are disabled by societal factors through their focus on meso and macro levels.

Conclusion

This paper provides support for the notion that disabled people in the performing arts face a range of barriers to their inclusion, establishing a framework that suggests barriers fit into one of the four overarching types: access, participation, representation and empowerment (APRE). Although there have been previous studies investigating social inclusion generally, as well as in the arts sector specifically, to the authors' knowledge this is the first attempt at positioning the barriers into an overarching explanatory typological frame. More notably, the APRE framework may have potential as a starting point to contribute to further refinement and consideration of the social model of disability. For example, Shakespeare (Reference Shakespeare and Davis2006) critiques the social model in relation to its blunt nature, arguing that it lacks nuanced consideration and understanding of the complexity inherent in social inclusion. The APRE framework provides one of the first models that can add nuanced consideration in this space, addressing one weakness of the social model by suggesting an interactive typology of four distinct, but inter-related, barriers to inclusion.

As this is the first study of its type, the need for replication of the framework, both across sectors and within the arts sector, has been identified as a priority for further exploration and refinement.

In terms of practical implications, a key intervention for management to facilitate inclusion is by engendering hope (Gidley, Hampson, & Wheeler, Reference Gidley, Hampson and Wheeler2010), a prime action from the national disability policy, that, in relation to the APRE frame, can be facilitated by empowering individuals. Empowerment is likely to have a positive impact on motivating people to think about their pathway in life (Egan, Butcher, & Ralph, Reference Egan, Butcher and Ralph2008, p. 35). In conjunction with access, participation and representation, empowerment provides the final part of the jigsaw puzzle of creating an integrated approach. This framework (APRE) can demonstrate how social inclusion in the arts has developed from a simple economic argument to a more nuanced understanding of not only why social inclusion is important, but also the barriers to its attainment.

The arts can contribute to communication, acknowledging disabled people human dignity and the significance of their social contribution (Bolt & Penketh, Reference Bolt and Penketh2016). Our study, therefore, provides implications for organisations to become ‘truly inclusive’ (Kawashima, Reference Kawashima2006; Ryan & Collins, Reference Ryan and Collins2008), moving beyond social justice to maximising human potential. Thus, working to remove the barriers identified in our study will provide the first small steps to providing greater hope to a significant group of people in society.

We wish to signal the breadth of this study, which included a number of different types of stakeholders (and thus potentially also its limitations). As noted by Camarero, Garrido, and Hernández (Reference Camarero, Garrido and Hernández2020), the mission of arts organisations is socially focused, with objectives that are both social and economic. As a result, their stakeholder lists are long and complex (Camarero, Garrido, & Hernández (Reference Camarero, Garrido and Hernández2020). Therefore, additional research could be undertaken to develop the framework, through studies that consider stakeholders separately: in particular, disabled audience members and/or consumers, disabled artists and performers, and, the awareness, understanding and attitudes of managers regarding the inclusion of disabled people.

Our framework helps to better understand and conceptualise inclusion issues facing disabled people. The key barriers identified in our study related to each of the four dimensions of social inclusion which can be explained by the social model of disability reinforcing that people are disabled by society, with barriers that range from physical to attitudinal. These findings have implications beyond social inclusion within the arts and demonstrate how the arts can empower disabled people and enable them to access, participate and represent themselves and have a voice if barriers are removed. As a final note, it is important to acknowledge that the barriers presented are not limited to disabled people and may indeed be applied to any individual or group facing barriers to inclusion. As such, considering this frame across a diverse range of individuals and contexts would be an important step to more fully understand barriers to inclusion in a more holistic way.

Dr. Ayse Collins is an Associate Professor in the Department of Tourism and Hotel Management, Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey. She obtained her PhD from Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey, where her thesis won the ‘Thesis of the Year’ award. Her research interests cover human resources management, labour law, curriculum development, performance evaluation, inclusion, social inclusion, disability and arts. She is the member of editorial boards of several international and national journals.

Dr. Ruth Rentschler OAM is Professor Arts & Cultural Leadership and Head, School of Management, University of South Australia. She has published widely on matters related to the diversity and the arts in journal articles, industry reports, books and conference papers. She has a strong service record both in universities and in the community, serving on non-profit boards, editorial boards and as conference and doctoral symposium organiser.

Dr. Karen Williams is a lecturer in the School of Management at the UniSA Business School. Karen's teaching and research lie in sociology, gender, disability, representation and inclusion and sport and leisure.

Dr. Fara Azmat is an Associate Professor in the Department of Management at Deakin University, Melbourne, Australia. Her areas of research interest are: social responsibility of small businesses, corporate social responsibility in developing countries, women entrepreneurship, poverty and sustainable development. She is currently serving as a member of the Editorial board of Social Responsibility Journal, a fellow and member of the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), Peer Review College UK.