Introduction

For those who are cognitively and physically frail, long-term care provides a place of collective living; for staff, it represents a place of work. Relationships between these two groups are, understandably, complex. The professionalization of care, the burden of care discourse, and the frailty of many residents all contribute to an uneasy power differential between those in need of care and those who are qualified to provide it (Barnes, Reference Barnes2006; Tronto, Reference Tronto1993). With disproportionate attention focused on caregiving, care is often assumed to be unidirectional, with those in receipt of care positioned as “passive and unable to contribute” (Brannelly, Reference Brannelly2016, p. 309). Such relational inequalities are all the more pronounced for residents who experience communication difficulties. Ward, Vass, Aggarwal, Garfield, and Cybyk’s (Reference Ward, Vass, Aggarwal, Garfield and Cybyk2008) ethnographic study found that a quarter of all long-term care staff–resident interactions lasted no longer than 5 seconds and that the great majority happened in silence. Under these circumstances, the response from the person cared for frequently goes unheard and unheeded (Kitwood, Reference Kitwood1997). Yet care interactions involving two or more people are inherently relational. Indeed, Brown Wilson’s (Reference Brown Wilson2013) ethnographic research suggests that older adults residing in long-term care do contribute to the process of care. Their influence will be minimal, however, unless these contributions are recognized and valued.

The invisibility of relational care in long-term care is an ongoing theme in scholarly writing (Armstrong & Braedley, Reference Armstrong and Braedley2013; Armstrong & Lowndes, Reference Armstrong and Lowndes2018; Brown Wilson, Reference Brown Wilson2013; Diamond, Reference Diamond1992). Diamond’s (Reference Diamond1992) landmark institutional ethnography, Making Grey Gold, reveals how the formal charting of caretaking tasks in nursing home care disregards their relational context. Armstrong (Reference Armstrong, Armstrong and Braedley2013) argues, similarly, that relational care remains invisible because it is under-valued. It is also under-explored in research. In 2009, Brown Wilson and Davies (Reference Brown Wilson and Davies2009) drew attention to the fact that there are a scarcity of studies examining relationships in long-term care. Ten years on, it would appear that little progress has been made. A majority of studies focus on caregivers and care receivers as separate groups. Few are designed to examine interactions between these two groups (Macdonald & Mears, Reference Macdonald and Mears2018). Indeed, as Tolhurst, Weicht, and Kingston (Reference Tolhurst, Weicht and Kingston2017) observed, there is a tendency, even in dyadic studies, to bypass conversational interaction and present findings as stand-alone individual-level data.

If relational care is, indeed, both under-valued and under-explored, then finding ways to make it more visible would seem important (Brown Wilson, Reference Brown Wilson2013). A synthesis of qualitative studies examining everyday care interactions between long-term care staff and residents who are living with dementia will help clarify the development of knowledge in this area and potentially contribute to its visibility. In this review, therefore, our objectives were twofold: (1) to establish what is known about relational care in this context, and (2) to synthesize what is known about what works into a new configuration of relational care knowledge.

A Working Definition of Relational Care

We have chosen to define relational care as a bidirectional process, one in which the agency of both people – those who give and those who receive care – is recognized (Tronto, Reference Tronto1993). This conceptualization of relational care is informed by two theorists from different disciplines: nursing and political science. Brown Wilson, a nursing scholar, is one of few researchers to focus on how relationships develop in the everyday care context of long-term care. In Caring for older people: A shared approach (Brown Wilson, Reference Brown Wilson2013), she identified “care that involves us all” (p. 130) as both a concept and an outcome that can be measured in the assessment of a relationship-centred approach to care. The route by which this outcome is achieved begins with valuing the contributions made by everyone – residents, families and staff – in the caring relationship. By contrast, Tronto’s (Reference Tronto1993) ethic of care was developed at the intersections of care ethics, feminist theory, and political theory, and has been used to discuss care in diverse academic disciplines, including dementia studies (Brannelly, Reference Brannelly2006, Reference Brannelly2016). Arguably Tronto’s most significant contribution to the field has been to reinstate care receiving as an essential phase of the care process. In Moral boundaries: A political argument for an ethic of care, Tronto (Reference Tronto1993) set out a 4 Phase Process of Care, with each phase aligned to a moral quality, as follows: (1) Attentiveness – caring about, (2) Responsibility – caring for, (3) Competence – care giving, and (4) Responsiveness – care receiving. Once care is given (Phase 3), Tronto argued, there will be a response from the person receiving care. Observing their response and establishing whether the care given was adequate requires the moral quality of responsiveness (Phase 4).

The interfacing ideas of Brown Wilson and Tronto offer a lens through which to make the relational nature of care more visible and the voices of those who receive care more audible. Both were instrumental in our delineation of inclusion criteria for this review.

Methods

Meta-Ethnography

We chose meta-ethnography as our review methodology. Meta-ethnography is a method of synthesizing qualitative research, first described by Noblit and Hare (Reference Noblit and Hare1988), and now widely used in health care, to develop theoretical understanding of complex phenomena (France et al., Reference France, Cunningham, Ring, Uny, Duncan and Jepson2019).

Noblit and Hare (Reference Noblit and Hare1988) describe the process of meta-ethnography as “a series of phases that overlap and repeat as the synthesis proceeds” (p. 26). These phases include: getting started, deciding what is relevant to the initial interest, reading the studies, determining how the studies are related, translating the studies into one another, synthesising translations, and expressing the synthesis. Rather than being a sequence of phases, however, meta-ethnography entails a dynamic and continuous process of comparison and interpretation, during which qualitative studies are translated into and, therefore, made sense of in terms of one another. In this way, insights are combined to offer a more complete understanding of the phenomenon in question (Noblit & Hare, Reference Noblit and Hare1988). In their evaluation of meta-ethnography, Campbell et al. (Reference Campbell, Pound, Morgan, Daker-White, Britten and Pill2011) found the method effective in “establishing what is known and what remains unknown or hidden about a topic at a given point in time” (p. 119). In light of a perceived under-representation of relational care in long-term care research and practice, meta-ethnography was deemed an appropriate methodology.

As Noblit and Hare (Reference Noblit and Hare1988) point out, “all syntheses begin with some interest on the part of the synthesizer” (p. 40). Our review team brought a variety of perspectives to the task. These were informed by professional backgrounds in social work, nursing, creative arts therapy, sociology, and rehabilitation sciences, along with research interests in communication, knowledge translation and narrative, and arts-based approaches to explore illness, disability, and end of life. Our shared interest was in researching relational care.

Following, we discuss our methodology under two broad headings: Search and Selection and Translation and Synthesis.

Search and Selection

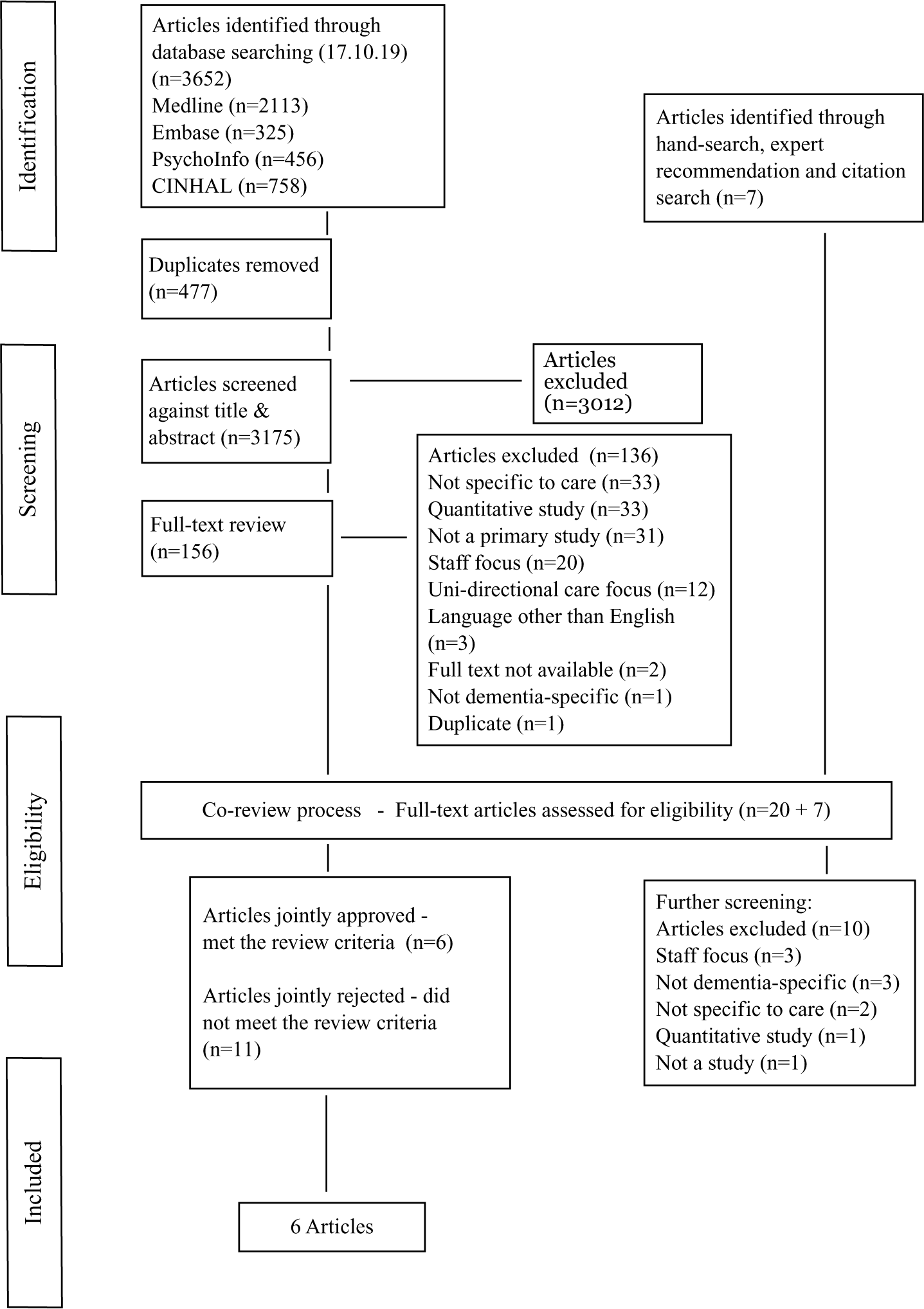

A comprehensive search strategy was developed through team discussion and was conducted by first author and a Faculty of Health Sciences librarian. Search term categories aligned with our review topic as follows: context (long-term care), population (elderly), and phenomenon of interest (relational care), defined as “a bi-directional process of care”. We learned, through trial and error, that replacing the term “dementia” with “elderly” in the context of “long-term care” produced more promising results, without excluding the target population. In addition, we included the term “personhood”, because Kitwood’s (Reference Kitwood1997) use of this term has framed the dementia experience as relational (Brooker, Reference Brooker2004). The search strategy was developed in MEDLINE® (Ovid) using a combination of subject headings and keywords. It was then adapted for the following databases: Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), PsycInfo and Embase, using their respective subject headings. See Appendix 1 for the MEDLINE search strategy. Our search was conducted on October 17, 2019, yielding 3,652 results. These were entered in Covidence, a systematic review management system, where duplicates were removed. The first author then screened the remaining articles, initially by title and abstract, whereupon a further 3,012 articles were removed, and then by full text. On close reading, a further 136 articles were excluded. A citation search was performed for each of the remaining 20 articles, which resulted in an additional seven articles. Figure 1 shows a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram that provides an overview of the selection process and grounds for exclusion.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

The PRISMA flow diagram details our review’s search and selection process.

Selection Criteria

The second phase of our selection process involved close reading of the remaining 27 articles by the first and fifth authors, who met to discuss each article’s eligibility for inclusion. To prepare for these meetings, both reviewers independently filled out a customized full-text review table that served as a checklist for our selection criteria. These required that all eligible articles (1) document a qualitative study, (2) be set in a residential care facility, and (3) involve participants living with dementia. Although an actual diagnosis of dementia was not essential, evidence of impaired cognitive and communicative abilities was, and this criterion required validation through the inclusion of data such as quotations and field note entries. In addition, eligible studies needed to include: (1) a focus on resident–staff interactions during everyday care activities, and (2) data corresponding to our definition of relational care, in which the resident participants were visible and/or audible. By default, this necessitated data collection methods designed to accommodate both verbal and non-verbal communication.

Noblit and Hare’s (Reference Noblit and Hare1988) approach to meta-ethnographical synthesis does not include a formal process of quality appraisal. Rather, they recommend that studies be judged in terms of their relevance and contribution to the topic of interest; and that their worth be “determined in the process of achieving a synthesis” (p. 16). Because the concept of relational care was rarely named as such, we relied on Tronto’s (Reference Tronto1993) 4 Phase Process of Care to guide our identification of relational care practices. At times, this brought to light inconsistencies between first order constructs (raw data such as participant quotations and field note observations) and second order constructs (the researchers’ interpretations of these) (Britten et al., Reference Britten, Campbell, Pope, Donovan, Morgan and Pill2002). The question of how researchers interpret what they see was particularly relevant when first order constructs included field note descriptions of non-verbal communication; or when a response from the person receiving care was missing, although the author reported the interaction to have been positive. Detailed discussions of this nature led to greater precision in the delineation of our selection criteria. They also helped to define worth in terms of the quality criteria Tracy (Reference Tracy2010) has proposed for qualitative research. To justify inclusion, an article needed to demonstrate (1) “rigour” in terms of providing “sufficient data to support significant claims”; (2) “credibility” in terms of “thick description, concrete detail, explication of tacit (non-textual) knowledge and showing rather than telling”; and (3) “meaningful coherence” in terms of achieving “their stated purpose” and accomplishing “what they espouse to be about” (p. 840). A further 11 articles were excluded at this stage. See Table 1 for a complete list of our inclusion criteria.

Table 1. Inclusion criteria

The co-review process resulted in 6 of the 27 articles being retained for synthesis. See Table 2 for an overview of the included articles. Our reasons for excluding articles at this stage included: (1) the voice (verbal and non-verbal) of the person receiving care was thinly represented (Criterion #5); (2) descriptions of the care process stopped short at Phase 3 of Tronto’s 4 Phase Process of Care; that is, links between the care given, the care receiver’s response, and staff responsiveness were missing (Criterion #6); (3) a disparity existed between first and second order constructs; that is, the data provided did not sufficiently substantiate the authors’ interpretations (Criterion #7).

Table 2. Overview of included articles

Translation and Synthesis

Noblit and Hare (Reference Noblit and Hare1988) employ the concept of translation to describe an iterative process of constant comparison during which concepts from one study are translated into and, therefore, understood in terms of the others, and vice versa. This process began during the focused discussions of our selection phase, when conceptual similarities among the studies were noted. These similarities included some recurring attributes of relational care practice as well as factors that seemed to foster its development. To complete this process, the first author re-read the six included articles to identify key descriptors for each commonality (Doyle, Reference Doyle2003). The first and fifth authors then independently searched across the articles for the same or equivalent descriptors. For example, in three of the articles, a distinction is made between interactions that include and interactions that exclude those receiving care (A1, A3, A6). In Clarke and Davey’s article (A1, 2004), this idea is expressed in terms of staff who “did for the residents in their care rather than allowing them to make their own decisions” (p. 23). The same idea and wording appear in Watson’s article (A6, 2019): “staff tried to do things for residents which they could still do themselves” (p. 555). The opposite process of doing with was also a term used to describe a bidirectional process of care in two of the articles (A2, A5). In this way, the concept of doing with versus doing for was eventually translated across all six articles. Through discussion, four further conceptual categories were agreed on, and a similar translation process was performed for each. To synthesize the translations, the first author drafted an overarching model that brought together the key findings into a line of argument synthesis (Noblit & Hare, Reference Noblit and Hare1988) or new “storyline” (Noblit, Reference Noblit2016, p. 4). The model and accompanying narrative were then discussed with all of the review authors, and a number of modifications were made.

Results

The studies included in a meta-ethnography will relate to one another in different ways, and this will determine the type of synthesis. Reciprocal translation is undertaken when studies are about similar things; when studies are dissimilar or refute one another refutational translation is recommended (Noblit & Hare, Reference Noblit and Hare1988). Our finely tuned inclusion criteria necessitated that all of the eligible articles share a number of common characteristics (see Table 1). As such, reciprocal translation proved a good fit. Our translation process resulted in five common, conceptual categories: doing with versus doing for, staff responsiveness, resident agency, inclusive communication, and time. Following, we discuss how each conceptual category aligns with each of the included articles.

The ways in which researchers interpret and write about what they see will be shaped by particular discourses about the topic under study (Noblit, Reference Noblit2016). Altogether, the articles span 15 years of dementia studies (2004–2019), during which time scientific and cultural understandings of dementia have evolved considerably (Bartlett & O’Connor, Reference Bartlett and O’Connor2010). Conceptual differences arising from shifts in the interpretive context were noticeable across the articles and will also be discussed.

Doing with versus Doing for

The concept of doing with versus doing for was chosen to represent the overall process of relational care; whereas staff responsiveness and resident agency represent constituent parts. Although we discuss each of these concepts separately, they are closely inter-related. In Table 3 Footnote 1, we summarize the translation process for each category and the inter-relationships between them. Each vertical column shows how the three concepts interconnect within the unique storyline of each article, whereas reading across the rows allows for comparisons to be made across all six articles (Erasmus, Reference Erasmus2014).

Table 3. Reciprocal translation of key concepts

Doing for is associated with a caregiver’s under-estimation of a resident’s capacity to participate in the care activities (A1, A3, A6). This places the resident in a “passive position” (A3, Hammar et al., Reference Hammar, Emami, Engström and Götell2011, p. 163) and can lead to a uni-directional or task-focused approach to care (A1, A3). The tendency to exclude a resident from participating in care activities is attributed variously to a lack of caregiver knowledge and skills in capacity assessment (A1), a task-focused care culture (A1, A3) and the influence of dominant discourses, such as the biomedical focus on progressive functional decline (A4), or social death (A6).

By contrast, doing with implies that care activities are inclusive and that both people in the relationship are somehow working together. Two articles (A2, A5) focus exclusively on naturally occurring inclusive care practices. As such, the theme of doing with is implicit in the first order constructs, which include detailed “communicative exchange patterns” (A5, Corwin, Reference Corwin2018, p. 729). Elsewhere, this type of care interaction is variously described as participatory (A1, A2, A3, A5), cooperative (A3), and collaborative (A2). In Dran’s article (A2, 2008), for example, the author describes a process during which staff worked with a resident “to complete the meaning of a situation or a story” (p. 644). Dran describes this quality of interaction as “a collaborative effort” (p. 642) and is careful to highlight the agency of both people: the resident, who initiated the episode, and the staff member, who went along with and did not try to correct “the resident’s perception” (p. 646). However, doing with is also characterized as enabling in two of the articles (A1, A6). Indeed, in the case of severe dementia, Watson (A6, 2019) describes the caregiving/care-receiving relationship as “asymmetrical”, because it requires staff to take the initiative (p. 559). This more nuanced understanding of doing with would seem to fit with Doyle and Rubinstein’s (A4, 2014) vision of “a greater equality and empathy contained within the care relationship” (p. 958). In the context of communication challenges, this involves, as Brannelly (Reference Brannelly2016) has argued, creating space for people with dementia to make their own decisions (A1), preserve their sense of self (A2), try things for themselves (A4), participate in conversations (A5), and do the things they can still do (A6). Therefore, doing with requires a certain aptitude on the part of staff, which we have named staff responsiveness.

Staff Responsiveness

We chose staff responsiveness as an umbrella term to cover a number of relational care skills mentioned in the articles. As discussed, doing with involves creating space for residents to participate in care activities; however, in a dementia care context, it also involves an ability to recognize when a resident is able to make their own decisions and do things for themselves (A1, A6). Capacity assessment, as Clarke and Davey (A1, 2004) advise, is a skill that can be developed through education and training. It can also be acquired through “personal exploration” (p. 22) or, as Watson (A6, 2019) suggests, through “doing and experiencing” (p. 554) in the course of care work. There are two main skills that would seem to facilitate this learning. The first skill can be summarized as “being open” (A6, Watson, Reference Watson2019, p. 556), and is variously described in the articles as “genuine interest in and engagement with the resident” (A1, Clarke & Davey, Reference Clarke and Davey2004, p22), a caregiver taking their cue from a resident (A2 Dran, Reference Dran2008, p. 643), inviting communication (A3, Hammar et al., Reference Hammar, Emami, Engström and Götell2011, p. 163), and “paying attention and expecting a response” (A6, Watson, Reference Watson2019, p. 556).

The second skill connects with the theme of visibility and can be summarized as noticing or awareness. In two of the articles, for example, doing with is seen to occur when a resident and their abilities are more visible to staff (A3, A6). Hammar, Emami, Engström, & Götell (A3, 2011) observed that during caregiver singing situations, as staff became more intensely aware of residents, they communicated differently: they “expressed a willingness to co-operate” (p. 166) and more often left space for residents to “try to do things themselves before helping” (p. 165). Similarly, Watson (A6, 2019) contrasts staff who enable residents to “do the things they can still do” (p. 559) with those who “fall into the habit of seeing residents as passive” (p. 555). In summary, both skills place an emphasis on doing with and, therefore, work against attitudes more often associated with doing for, such as under-estimating, ignoring, or overriding resident contributions to care (A1, A3, A4, A6).

Resident Agency

In line with our inclusion criteria, resident agency is recognized and visible in the first order constructs of all six articles and, during the translation process, we chose this term to encompass the different levels of agency represented. In four of the articles, when care interactions fell under the doing with category, resident agency was described as engagement or participation. This active response was captured in the data both verbally and non-verbally through descriptions of body movements, singing, laughing, eye contact and touch (A1, A3, A5, A6). Indeed, in five of the articles (A1, A3, A4, A5, A6) we see how embodied expression was used by the resident participants to compensate for verbal communication difficulties.

Resident responses during interactions that fell under the category of doing for were also represented. However, authors in just two of the articles recognized non-verbal communication in such circumstances as attempts to express care needs (A4) or as responses to care (A6). In large part, this disparity can be explained historically. As scientific and cultural understandings of dementia have evolved, researcher engagement with the significance of non-verbal communication has increased (Bartlett & O’Connor, Reference Bartlett and O’Connor2010). Hammar et al. (A3, 2011), for example, adopt a biomedical frame to organize their data in terms of problematic behaviours thought to be symptomatic of the disease process: “compliant”, “resistant and aggressive”, “confused”, and “disruptive”. In contrast, the later articles reflect a significant shift towards understanding behaviours as responsive and, therefore, as meaningful communicative action (Dupuis, Wiersma, & Loiselle, Reference Dupuis, Wiersma and Loiselle2012; Gilmour & Brannelly, Reference Gilmour and Brannelly2010). In Doyle and Rubinstein’s (A4, 2014) detailed field note account, for example, Raúl’s repeated and frustrated attempts to express his care needs – by “pulling at his pants and … saying that he needed to get in “the room” (p. 957) – are extremely visible, despite staff oblivion. Similarly, Corwin (A5, 2018) draws attention to the interactive sounds and expressions that signify a resident’s engagement in conversation irrespective of staff comprehension. Lastly, in Watson’s article (A6, 2019) resident responses to care, such as spitting out food or not making eye contact, are legitimized as small acts of “embodied agency” that indicate a resident’s active involvement in the caregiving/care-receiving interaction (p. 554).

Inclusive Communication

Although spoken instruction is, by and large, the dominant mode of staff interaction reported, authors in three of the articles discuss alternative approaches to communication that include a creative dimension or art form. Dran’s (A2, 2008) article reveals how biographical knowledge can be “seamlessly integrated” into the present context of care through spontaneous role play (p. 645), thereby providing an experience of acceptance and belonging for the resident (p. 646). Hammar et al. (A3, 2011) highlight the potential for singing to enhance communication during morning care. They note, for example, that residents “were more active in both getting dressed and communicating” and that verbal instructions or requests became unnecessary (p. 166). Similarly, Corwin (A5) reveals how the sharing of jokes and narratives creates opportunities for residents to engage in meaningful interaction without the risk of communicative breakdown. In each of these examples, the arts are seen to facilitate a more democratic relationship that cuts across the usual staff–resident power differential. Hammar et al. (A3, 2011) suggest, for example, that singing together enabled staff to see residents as “whole human beings” (p. 166). Doyle and Rubinstein (A4, 2014) suggest similarly that opportunities for staff to learn about the “narratives and perceived realities” of residents might offer an antidote to othering practices (p. 961). This, they caution, would necessitate more time for care activities.

Time

One of the oft-cited obstacles to relational care in long-term care is lack of time. Without discounting the significant time pressures under which front-line staff operate, in this review time does not appear to be a significant variable. Clarke and Davey (A1, 2004) explain that their observation methods were designed “to fit in” with the long-term care routine, during which the staff they observed were allocated a prescribed number of residents. Similarly, Hammar et al. (A3) recorded morning care situations, with and without caregiver singing, that lasted the same amount of time. Corwin’s article (A5, 2018) discusses “naturally occurring interaction” that occurred during care activities, such as foot massage, that lasted an average of 15 minutes (p. 725). Watson (A6) found, similarly, that body work provided opportunities for staff to connect with residents one-to-one and that staff had little time to spend with residents beyond body work. Lastly, Dran repeated a number of times that episodes of mistaken identity were brief, unrehearsed, and seamlessly integrated into the task at hand. How staff perceived and used the available time did seem to vary however. For example, Clarke and Davey (A1, 2004) report that for some staff, an “obsession with time” became a barrier to inclusive care. Their delivery of information was seen to be rushed, and residents were not always given sufficient time to respond. By contrast, during doing with situations, staff were seen to approach time differently. They appeared to have a “cheery and personal demeanour” and to encourage recall (p. 17). Hammar et al. (A3) found, likewise, that staff and residents operated at different paces and that some staff did not wait for a response after posing a question or interrupted the resident as they attempted to participate. By contrast, when staff sang for or together with residents, the pacing of care activities seemed to be more accommodating.

Summary of Findings

We chose the term doing with to represent care practices in which both parties are actively engaged in the care activities, albeit in different ways. In the context of communication challenges, we learned that this requires leaving space for residents to participate. Space in which they can, for example, make their own decisions, try things for themselves, do the things they can still do, interact socially, and preserve their sense of self. Therefore, during care termed as doing with, the person receiving care and their contributions to care are distinctly more visible. We also learned that leaving, or indeed, creating space for residents to participate during care activities does not necessarily require more time, but does involve a number of skills. These skills are obtained through specialized training but equally, they are obtained through experience acquired in the course of care work. They include: (1) an openness to the resident during the care activities, (2) an ability to recognize when a resident is able to make their own decisions and to do things for themselves, and (3) a sensitivity to non-verbal communication as a means towards more inclusive communication. Sensitivity to non-verbal communication would seem key in re-centering residents during care activities. Furthermore, it became apparent that as researchers engage with the meaning of non-verbal communication, resident contributions to care become more visible and residents themselves are brought “to the fore as key players in the caring relationship” (A6, Watson, Reference Watson2019, p. 552).

Synthesizing the Translations

In this section of our synthesis, we integrate these findings into a visual model (see Figure 2). Because our objectives are to understand the process of relational care and contribute to its visibility, the model is designed to spotlight the different components of doing with interactions that were seen to contribute to more inclusive, relational care practices in the six reviewed articles. The overlapping circles designate the staff–resident relationship. The dotted circle characterizes staff responsiveness as a circular process, and the bidirectional arrows indicate how first-hand experience feeds into experiential knowledge and vice versa. The three boxes – inclusive communication, education, and experiential knowledge – along with the broader institution-wide culture, represent contextual factors that can positively impact the interactive space. The interactive space is discussed in more detail in the next section.

Figure 2. New configuration of relational care.

The new configuration model shows different components of doing with interactions seen to contribute to relational care practices.

Discussion

Brannelly (Reference Brannelly2016) argues from an ethics of care standpoint that “it is the responsibility of society to create the space and place for people with dementia to contribute” (p. 311). As highlighted in our summary, a doing with approach to dementia care involves leaving or creating space for residents to participate during care activities. In our model, we have delineated and defined this space as the interactive space. It is both literal, because it involves a physical encounter, and conceptual, because it requires a particular orientation. As such, the interactive space exists as a potential space. It can be filled by doing with but, equally, it can be closed by doing for. In the discussion that follows, we tease out and expand on the different dimensions of a doing with orientation. We begin by explaining what we mean by “inclusive communication”.

Inclusive Communication

There is general consensus that people receiving care should be involved in the process, whatever the level of their impairment (Clare & Cox, Reference Clare and Cox2003). Furthermore, from a human rights perspective, Clare and Cox (Reference Clare and Cox2003) point out, those who communicate differently should be allowed to communicate on equal terms and from their own perspective (p. 935). As this review illustrates, however, in a dementia care context inclusion is difficult to achieve and there is clearly a need to “to identify the kinds of interactions” that allow for more equal communication during care activities (Webb, Reference Webb2017, p. 1105).

Full awareness of residents as contributing partners during care interactions has developed over time, as our understanding of dementia has evolved (Bartlett & O’Connor, Reference Bartlett and O’Connor2010). Engaging with the significance of non-verbal communication has been critical in this evolution (Hubbard, Cook, Tester, & Downs, Reference Hubbard, Cook, Tester and Downs2002; Kontos, Reference Kontos2004) and, as the findings from this synthesis reveal, a sensitivity to alternative forms of expression is certainly a stepping stone towards more inclusive communication. Yet the question remains, when verbal communication is the more dominant mode, how equal or inclusive can the interaction be? Three of the six articles in this review feature alternative modes of communication, including role play, singing, and narrative. In each, the resident participants seemed more able to participate on their own terms and, as Corwin (A5) phrased it, without risk of communicative breakdown. Furthermore, a creative approach to communication during care activities appeared to foster a more equal exchange that cut across the usual staff–resident power differential. That the arts are a great leveller was demonstrated in a study by Kontos, Miller, Mitchell, and Stirling-Twist (Reference Kontos, Miller, Mitchell and Stirling-Twist2017) exploring reciprocal engagement between elder clowns and residents with dementia in a long-term care setting. The study findings revealed a capacity in residents, often with severe symptoms of dementia, to reciprocate and, equally, “to initiate affective, creative, and playful” interactions (p. 60). These authors drew attention to residents’ “creative and imaginary capabilities”, which, they argued, are rarely supported in dementia care (p. 60). The incorporation of an alternative expressive mode would seem both to support resident participation and allow for more equal communication. In our model, we group together communication through the arts with other non-verbal modes of communication under the broad umbrella of inclusive communication. Our findings suggest that these kinds of interactions engender opportunities for residents with communication difficulties to participate on more equal terms.

A Worthwhile Activity

In a care culture more often focused on efficiency than on “residents’ need for slowness” (Armstrong & Lowndes, Reference Armstrong and Lowndes2018, p. 63), it is easy to see why doing for a resident during care activities is, by and large, the default approach. During doing with situations, however, staff were seen to approach time differently. In Hammar et al.’s article (A3), for example, when staff sang for or together with residents, the pacing of care activities seemed to be more accommodating. Overall, we learned that allowing space for residents to participate during care activities does not necessarily require more time. It does require us to think differently about how we value that time, however, and, as Tronto (Reference Tronto2015) has written, “that means first noticing it as time we’re spending doing worthwhile activities” (p. 29). Tronto’s (Reference Tronto1993) 4 Phase Process of Care redefines care as a relational activity that plays a role in mediating relationships (Tronto, Reference Tronto2015). This, as our findings indicate, involves relational skills such as being open to the person receiving care, inviting their participation and following their cue, expecting their response, and noticing their contribution. In summary, then, a doing with orientation during care activities would seem to depend on a more inclusive approach to communication, a different understanding of time, and, perhaps, also, a different way of thinking and talking about care.

A “Caring with” Institution-Wide Culture

The professionalization of care in long-term care has led to a top-down organization of care work in which “experts arrange processes of care for less-skilled care workers to carry out” (Tronto, Reference Tronto2015, p. 165). This situation, as Clare and Cox (Reference Clare and Cox2003) point out is not the best foundation for promoting inclusion; or, indeed, for recognizing soft skills, of the kind just mentioned, that are used by staff to build and maintain relationships (Armstrong, Reference Armstrong, Armstrong and Braedley2013). Aside from Doyle and Rubinstein (A4), the authors included in this review do not address the broader long-term care context in which their studies took place. The focus of our review is similarly narrow. Although we were guided by a definition of relational care based on Tronto’s (Reference Tronto1993) 4 Phases of Care framework, our topic was limited to resident–staff interactions. In failing to provide a more complete picture of institutional care, there is a risk that those who provide care will be blamed for decisions made by those who oversee care (Tronto, Reference Tronto2015). However, the majority of articles included in this review bring to light relational care practices in which the agency of residents and the initiative of staff are equally visible. Furthermore, authors in three of the articles infer that the observed staff responsiveness was acquired through experience gained in the course of care work. This finding concurs with research by Scales, Bailey, Middleton, and Schneider (Reference Scales, Bailey, Middleton and Schneider2017) that highlights the creative, often unrecognized, care work performed by frontline staff in hospital-based dementia wards. These authors recommend that more is done to recognize, support, and develop “the creative capacity of this workforce and their potential role in collectively producing change” (p. 240).

In later work, Tronto (Reference Tronto2013) added a fifth phase to the 4 Phases of Care framework: Solidarity – caring with, which is intended to situate care within a broader social context. A caring with institution-wide culture is one in which differing contributions to the caring relationship are recognized, and conversations about care include all those directly involved (Brown Wilson, Reference Brown Wilson2013; Tronto, Reference Tronto2015). The later articles included in this synthesis indicate a new trend towards acknowledging the experiential knowledge and skills of front-line staff in long-term care. Overall, our findings suggest that as researchers shift their focus to what is working during care interactions, relational care becomes more visible.

Implications for Research and Practice

Each of the studies reviewed in our synthesis succeeds in making relational care more visible. Although detailed discussion of the methods employed for this purpose is beyond the scope of this article, their collective contribution to research and practice is worth mentioning in three regards. By employing data collection methods that capture both verbal and non-verbal communication, these researchers underline the importance of visual data in monitoring inclusiveness during care activities. Furthermore, by designating gestures and non-verbal sounds as measures of engagement and participation, they create a more democratic research environment for people with communication difficulties. This is particularly significant for long-term care residents, who are under-represented in research (Luff, Laybourne, Ferreira, & Meyer, Reference Luff, Laybourne, Ferreira and Meyer2015). Lastly, by drawing attention to relational care practices already in operation, they give this work “the attention it deserves” and make these skills more available to others (Driessen, Reference Driessen, Krause and Boldt2017, p. 127). Through their efforts, we have been able to shine a light on relational care practices already in operation and wish to encourage further research in this area. In this regard, each of the articles offers valuable methodological guidelines.

Strengths and Limitations

During the search and selection process for this meta-ethnography, we identified only six articles that met our selection criteria. This is in part the result of a general scarcity of research examining relational care. It is also the result of our purposeful selection of studies during the co-review process. Our finely tuned eligibility criteria ensured that each of the included articles attained credibility in terms of “thick description”, “concrete detail”, and “explication of tacit (nontextual) knowledge” (Tracy, Reference Tracy2010, p. 840). In turn, this led to an in-depth synthesis. Although the review findings were certainly robust enough to provide a fresh configuration of relational care (France et al., Reference France, Cunningham, Ring, Uny, Duncan and Jepson2019), some aspects require substantiation, and there are gaps that need filling. For example, friends and family, whose contribution to care in long-term care is considerable and especially valued by residents (Milte et al., Reference Milte, Shulver, Killington, Bradley, Ratcliffe and Crotty2016), were excluded. A more representative interpretation of relational care would need to account for the triadic nature of many care interactions (Tuijt et al., Reference Tuijt, Rees, Frost, Wilcock, Manthorpe and Rait2020). The focus of this meta-ethnography was also limited to the interactive process – the giving and receiving – of care, rather than the quality of care provided. Nonetheless, although the configuration is far from complete, it does provide “a new interpretive context” for relational care (Noblit & Hare, Reference Noblit and Hare1988) and future reviews on this topic.

Lastly, our selection criteria excluded a significant body of book-length nursing home ethnographies (Vesperi, Reference Vesperi, Henderson and Vesperi1995). These typically combine micro-analysis of everyday care interactions with a broader, macro-analysis of the organizational context, and may help to explain both how and why relational care is so often overlooked.

Conclusions

To date, there have been few studies that examine care as a bidirectional process in long-term care, and still fewer that describe the participation of residents who are experiencing communication difficulties. In this article, our objective was to understand the development of knowledge in this area by means of a meta-ethnography. The review findings suggest that a relational, or doing with, approach to care is being practiced in residential care settings, albeit sporadically. To underscore collective understandings arising from our synthesis, we provide a new configuration of relational care that brings together what is known about what works. As such, we hope to have joined forces with these researchers in making relational care more visible. As Campbell et al. (Reference Campbell, Pound, Morgan, Daker-White, Britten and Pill2011) have pointed out, however, meta-ethnographies can help to reveal both what is known and what is not known about a given topic. In this regard, further research is needed to gauge more fully the differing contributions of staff, residents, and family to this joint endeavour of relational care.

Acknowledgments

We thank Karine Fournier, Research Librarian at the Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of Ottawa, for her assistance with the literature search.