Globally, communities that had little role in creating climate change are bearing the brunt of its effects. Large populations in non-industrialized countries depend on predictable rains, fertile land, and healthy fisheries; they have higher exposure to extreme weather than citizens in developed countries, yet fewer resources to invest in adaptation (Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative 2019). Two-thirds of Africans surveyed between 2016 and 2018 who had heard of climate change reported that it negatively affects their lives (Selormey and Logan Reference Selormey and Logan2019). These concerns fuel activism. Citizens mobilize protests, contact politicians, and start social media campaigns to advocate for effective mitigation and adaptation policies. Even in countries that are not the primary drivers of climate change, citizen pressure on national governments can counterbalance big international firms, such as plastics lobbyists, and can force governments to exert influence over major polluters (Hadden Reference Hadden2015; Riofrancos Reference Riofrancos2017). Further, citizen input is critical for local policymaking. Although climate goals can be set at the national level, local governments often have a decisive role in crafting and implementing policy (Ojwang et al. Reference Ojwang, Rosendo, Celliers, Obura, Muiti, Kamula and Mwangi2017). A core insight of environmental justice movements is that local efforts must incorporate the perspectives of marginalized communities to meet citizens’ needs effectively (Schlosberg Reference Schlosberg2004). In sum, local and national citizen engagement ensures that climate policy solutions serve impacted populations.

However, despite its salience, this issue does not prompt action from all citizens equally. Even groups that care passionately about the cause may abstain from participation because they do not believe they can influence the government. Efficacy—the belief that one’s actions can create change—links environmental concerns to activism (Lubell, Zahran, and Vedlitz Reference Lubell, Zahran and Vedlitz2007; Mohai Reference Mohai1985; Roser-Renouf et al. Reference Roser-Renouf, Maibach, Leiserowitz and Zhao2014).

The case of Kenya illuminates the determinants of environmental efficacy in non-industrialized countries more broadly. Kenya is highly impacted by climate change. In recent years, the country has experienced many extreme weather events, from droughts to deadly floods. Kenyans also have an established repertoire of environmental activism and progressive environmental policies, from Wangari Maathai’s Green Belt Movement to the 2017 plastic bag ban (e.g. Maathai Reference Maathai2003; Michaelson Reference Michaelson1994). Therefore, it is not surprising that Kenyans’ environmental efficacy is among the highest on the African continent (refer to the online appendix). However, not all Kenyans feel empowered to combat climate change. Even in a context of high environmental activism and concern, citizens’ efficacy is uneven across the country.

To understand what stymies environmental efficacy, we consider the prominent hypothesis that religion shapes environmental outlooks. Globally, religious affiliation correlates with climate change attitudes (Arbuckle and Konisky Reference Arbuckle and Konisky2015; Lewis, Palm, and Feng Reference Lewis, Palm and Feng2019; McCright and Dunlap Reference McCright and Dunlap2011; Veldman Reference Veldman2020). Religious institutions generate frames communicating the existence, causes, and urgency of climate change. In Indonesia, for instance, Muslim civil society organizations urge citizens to respond forcefully to the threat (Amri Reference Amri, Veldman, Szasz and Haluza-DeLay2013), a stance rooted in what Islamic scholars identify as the doctrine’s ecological values (Izzi Dien Reference Izzi Dien2000; Saniotis Reference Saniotis2012). Through Laudato Si’, Pope Francis similarly mobilizes Catholics globally. Religious leaders have access to powerful strategies of persuasion and wide-ranging mobilizational frames (McClendon and Riedl Reference McClendon and Riedl2019). Kenya features a high level of religious diversity, making it a propitious setting in which to examine how religious institutions shape agency, even within a polity in which many citizens are actively working to combat climate change. We find that membership in religious institutions does, in fact, impact efficacy in Kenya. However, we provide evidence that these impacts are not through doctrinal and ideological persuasion alone. Instead, they reflect experiences of group marginalization vis-à-vis the state, which are channeled through religious institutions.

Group marginalization can suppress citizens’ beliefs in their abilities to effect change. Efficacy develops through a learning process, reflecting prior experiences engaging the state (Beaumont Reference Beaumont2011; Finkel Reference Finkel1985; Hunt Reference Hunt2014; Mettler and Soss Reference Mettler and Soss2004). Feelings of representation and experiences successfully impacting policy change increase a citizen’s sense of agency (Finkel Reference Finkel1985). However, the perception that the state has underrepresented, neglected, or oppressed one’s group decreases citizens’ expectations that their actions will elicit a systemic response (Abramson Reference Abramson1972; Parker and McDonough Reference Parker and McDonough1999; Sidanius et al. Reference Sidanius, Cotterill, Sheehy-Skeffington, Kteily, Carvacho, Sibley and Barlow2016). Religious institutions and other community institutions sometimes channel marginalization into enhanced collective action (McDaniel Reference McDaniel2009; McAdam Reference McAdam1999), but they can also reinforce the perception that action is futile, in order to protect members against harassment and repression. Thus, community institutions shape the relationship between marginalization—a property of individuals and groups—and efficacy.

Kenya’s Muslims share a history of low representation in government and exclusion from the state (Elischer Reference Elischer2019; Ndzovu Reference Ndzovu2014). Recent Kenyan efforts to root out support for al-Shabaab and other extremist groups have increased that sense of marginalization (Mogire and Mkutu Agade Reference Mogire and Agade2011). Analyzing Afrobarometer surveys as well as nine focus groups and sixteen semi-structured clergy interviews in urban and rural Kenya, we show that Muslims express lower beliefs in their ability to impact environmental change than Christian peers of any denomination. We find that these differences do not result from differing exposure to or scientific beliefs about climate change. Instead, we argue that political marginalization, as experienced by individuals and shared within community institutions, limits Muslims’ efficacy.

Climate change has far-reaching impacts and requires a coordinated political response; this research reveals why some communities are less likely to engage. Scholars have demonstrated how membership in institutions can increase individuals’ ability to advance their interests through collective action (Hadden Reference Hadden2015; Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990). Less understood, however, is under what circumstances institutions reinforce the decision not to act. In examining what stymies efficacy in relation to environmental issues, we respond to the call for more political science research on responses to climate change (Javeline Reference Javeline2014)—an issue that is particularly understudied in non-industrialized countries. We demonstrate that experiences of historical and contemporary discrimination within the state can have long-lasting effects on which citizens participate in climate change activism. Without increased attention to the impacts of marginalization on efficacy, climate change policies will fail to meet the needs of vulnerable populations. Our study thus highlights the need for policy interventions to engender participation among marginalized groups—a key to creating inclusive climate change solutions.

Marginalization, Political Efficacy, and Community Institutions

Efficacy is an essential component of activism—linking concerns to action. In a basic model of collective action, citizens engage as a function of issue salience and perception of agency (i.e., efficacy).Footnote 1 These two attitudes correspond to the “B term” and the “p term” in a simple cost-benefit model of participation. In the case examined here, the “B term” reflects the level of concern about climate change (i.e., “Benefits”), whereas the “p term” reflects the probability of one’s action affecting the outcome (i.e., probability) (e.g., Riker and Ordeshook Reference Riker and Ordeshook1970). Even issues with extremely high salience will not translate into action without the accompanying belief that collective action will be fruitful.

Our conceptualization of environmental efficacy builds on scholarship on political efficacy. The latter refers to individuals’ beliefs that the political system will respond to them (Mokken Reference Mokken1971); in the African context, political efficacy is strongly linked to political participation (Hern Reference Hern2019). Similarly, citizens’ perceptions of their own ability to impact environmental outcomes—a construct we term “environmental efficacy”—is a critical determinant of environmental activism and mobilization (Ahn et al. Reference Ahn, Fox, Dale and Avant2015; Cleveland, Kalamas, and Laroche Reference Cleveland, Kalamas and Laroche2005; Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera Reference Hines, Hungerford and Tomera1987; Lam Reference Lam2006).Footnote 2

Efficacy is both domain-specific and contextual; it entails citizens’ evaluations of the outside world and their roles within it. Scholars often distinguish between two dimensions of efficacy: internal and external (Balch Reference Balch1974; Coleman and Davis Reference Coleman and Davis1976; Morrell Reference Morrell2003; Niemi, Craig, and Mattei Reference Niemi, Craig and Mattei1991). Whereas internal efficacy reflects the “individual’s beliefs that means of influence are available to him” (Balch Reference Balch1974, 24), external efficacy assesses external forces’ likely response to individual actions. Internal efficacy should depend on factors such as individual resources and social networks; in the domain of environmentalist action, external efficacy might depend on perceptions of both state responsiveness and the sources of climate change. As a result, institutions at multiple scales likely shape citizens’ environmental efficacy: from community groups and schools to local and national government.

Early socialization molds both internal and external efficacy. For example, foundational scholarship on American politics highlights that education and civic skills endow individuals with the confidence that they are equipped to participate effectively in politics (Brady, Verba, and Schlozman Reference Brady, Verba and Schlozman1995). Similarly, citizens grow in internal efficacy as they acquire information about the political system (Nie, Powell, and Prewitt Reference Nie, Powell and Prewitt1969). Across the developing world, citizens learn efficacy through civic education (Finkel Reference Finkel2003; Finkel and Smith Reference Finkel and Smith2011). In Mali, attending school, and particularly gaining fluency in French, the bureaucratic language, empowers citizens to interact with the political system (Bleck Reference Bleck2015). Yet social learning is context specific. Friedman et al. (Reference Friedman, Kremer, Miguel and Thornton2016) find no effect of girls’ secondary education on efficacy in Kenya. In Zimbabwe’s authoritarian context, Croke et al. (Reference Croke, Grossman, Larreguy and Marshall2016) find that higher levels of education are associated with reduced participation, due to deliberate disengagement.

Beyond education, past interactions with the government inform individuals’ evaluations of whether activism might succeed (Chamberlain Reference Chamberlain2012; Roser-Renouf et al. Reference Roser-Renouf, Maibach, Leiserowitz and Zhao2014). Hern (Reference Hern2019) argues that citizens feel empowered to act politically when they think that government is making efforts to provide services, while political elites perceived as untrustworthy or incompetent reduce “group efficacy” (Lubell, Zahran, and Vedlitz Reference Lubell, Zahran and Vedlitz2007). Social policies can also affect citizen agency (Hunter and Sugiyama Reference Hunter and Sugiyama2014), as can institutions ranging from direct democracy (Bowler and Donovan Reference Bowler and Donovan2002) to electoral rules (Karp and Banducci Reference Karp and Banducci2008) to regime types (Coleman and Davis Reference Coleman and Davis1976). Analyzing a panel survey, Finkel (Reference Finkel1985) shows that past participation impacts subsequent expectations of systemic responsiveness. The development of political efficacy is thus a dynamic process of “sociopolitical learning” (Beaumont Reference Beaumont2011). Efficacy is constructed over time, as citizens internalize past experiences and build expectations of their own future agency vis-à-vis the state.

Marginalization constitutes a form of group-based learning that saps citizens’ confidence in their own potential impact. Marginalization describes a persistent and structural position as a historically discriminated group in society or the political system. Social dominance theory argues that marginalization stymies non-dominant group members’ efficacy and willingness to confront the system (Sidanius et al. Reference Sidanius, Cotterill, Sheehy-Skeffington, Kteily, Carvacho, Sibley and Barlow2016). By limiting access to resources, marginalization leads citizens to question their own abilities. For instance, a dearth of visible political role models saps women’s internal efficacy (Thomas Reference Thomas2012). In addition, socialization as a second-class citizen can inhibit external efficacy, generating alienation and making citizens doubt whether the state will respond to their voices. In the United States, for instance, African Americans’ negative encounters with a “predatory system of government” that engages in “extractive policing” depress political participation and trust in the U.S. government (Lerman and Weaver Reference Lerman and Weaver2014; Soss and Weaver Reference Soss and Weaver2017; Weaver and Lerman Reference Weaver and Lerman2010; White Reference White2019). In short, negative experiences with the state diminish efficacy.

Marginalization is not solely an individual experience, but one shared within communities. Consequently, community institutions shape perceptions of and responses to oppression (Case and Hunter Reference Case and Hunter2012). By “community institutions,” we mean socially identified, locally bounded groups that generate forums for interaction, sets of formal or informal rules, and social hierarchies; examples range from religious congregations to neighborhood gangs. Repeated interactions within community institutions often reinforce marginalization. First, discussion among members who experience similar discrimination may amplify mistrust in the state or perceptions of non-responsiveness. Second, independent of personal experiences, citizens learn from other group members’ experiences, internalizing the perception of collective marginalization through shared narratives. Third, leaders bear witness to and recount the experience of marginalization; they may discourage certain types of political action, shape assessments of likely state responses, or provide or limit resources for participation. Groups targeted by the state might urge members to avoid mobilization, seeking to protect vulnerable members by socializing them to be cautious in interactions with the state and larger society. In most circumstances, community institutions serving marginalized populations will rationally draw inward, reinforcing narratives of marginalization in an effort to prevent further oppression of group members. All of these mechanisms at the community level may further erode citizens’ confidence in governmental responsiveness and their efficacy.

Nonetheless, under exceptional circumstances, community institutions instead increase marginalized populations’ efficacy. Black churches in the United States are a notable example. Scholars agree that historic marginalization has profoundly shaped African Americans’ agency and participation, producing low trust in government.Footnote 3 For example, Parker and McDonough (Reference Parker and McDonough1999) show that historical marginalization inhibits environmental activism, despite African Americans and white Americans having similar environmental concerns. However, churches leverage resources, networks, and hierarchies to channel action to address core group concerns, defying anticipated repression (McAdam Reference McAdam1999). They transmit information about key issues and mobilize congregants into politics (McDaniel Reference McDaniel2009). Further, churches generate opportunities for citizens to learn and exercise civic skills (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). As a result, African American churches have been a “platform for political learning” that helps communities overcome barriers to participation (Wald and Calhoun-Brown Reference Wald and Calhoun-Brown1997, 285).

Echoing McAdam and Boudet (Reference McAdam and Boudet2012), we argue that at least three conditions hold in cases where marginalized communities’ institutions increase efficacy and mobilization. First, leaders must identify a suitable political opportunity structure; institutions operating under moderate but not extreme repression are better able to advance empowering narratives. Second, scholars emphasize the role of resistance narratives that identify structural oppression, while simultaneously encouraging political action (Case and Hunter Reference Case and Hunter2012). Shingles argues that the development of Black consciousness empowered African Americans, enabling them to shift the locus of blame for poverty to the government (Reference Shingles1981, 89). Third, marginalized communities are most likely to surmount barriers to activism in response to issues framed as immediate threats to the community’s way of life or survival. For example, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Muslim institutions overcame political exclusion to mobilize for government support of religious schools (Leinweber Reference Leinweber2012). In the United States, migrant populations have channeled experiences of marginalization into collective action in response to perceived threat (Ramírez Reference Ramírez2013; Zepeda-Millán Reference Zepeda-Millán2017). As a result, climate change is a less propitious issue for marginalized groups’ mobilization under most circumstances, because it is not usually immediately urgent for survival. Only when environmental problems become imminent (i.e., local factories that pose a severe health threat, or mining-related pollution in indigenous reservations) do marginalized communities mobilize for environmental justice (McAdam and Boudet Reference McAdam and Boudet2012). While scholars often emphasize that community institutions can solve collective action problems (e.g., Magaloni, Díaz-Cayeros, and Ruiz Euler Reference Magaloni, Díaz-Cayeros and Euler2019; Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990), sustained marginalization does not easily translate into increased efficacy. Absent specific conditions, narratives shared within marginalized community institutions often reinforce the effects of systemic discrimination on individuals’ beliefs in their ability to effect change.

Thus, community institutions are prisms that refract marginalization, producing a spectrum of outcomes. In some circumstances, institutions channel marginalization into greater efficacy and activism, yet in other cases, they reinforce marginalization, reducing efficacy and activism. However, the impact of marginalization on efficacy has been under-explored in the context of the Global South. The following section presents the case of marginalized Muslim institutions and climate change policy in Kenya and our expectations in context.

The Case of Kenya

Climate Change and Environmental Activism

Climate change is a high-salience issue in Kenya that is currently impacting citizens’ lives. Kenyans have observed many extreme weather events in recent years, including droughts, flooding, and storm surges (Ongoma, Chen, and Omony Reference Ongoma, Chen and Omony2018). In a 2013 Pew survey, 57% of Kenyans perceived climate change as the top global threat (Kohut Reference Kohut2013). By 2018, this had increased to 71% (Poushter and Huang Reference Poushter and Huang2019).

At the time of fieldwork in 2018, Kenya had been experiencing substantial climate instability. Consider, for example, reporting in the Daily Nation newspaper over the six months prior to the August 2017 elections.Footnote 4 A sample of news stories provides a snapshot of the environmental topics discussed. Weather changes, such as drought and flooding, were by far the most frequently referenced issues. Although few instances were explicitly tied to climate change, and political campaigns did not incorporate climate change discourse, media coverage described how extreme and unpredictable weather was affecting Kenyans’ lives.

Awareness of the science of climate change in Kenya is high, given the country’s long history of environmental activism. In 1977, Wangari Maathai, a university professor and eventual member of Parliament, founded the Green Belt Movement to address deforestation, mobilizing rural women to plant trees and educate citizens on “ecological destruction” (Hunt Reference Hunt2014). The “consensus movement,” which eventually earned Maathai a Nobel Peace Prize, raised consciousness of environmental issues broadly (Michaelson Reference Michaelson1994, 546). In recent years, energy waste and pollution have also become increasingly topical, contributing to a nationwide plastic bag ban in 2017. The Green Belt Movement’s current platform includes efforts to aid rural communities in addressing climate change by restoring and protecting forests. In sum, due to Kenyan citizens’ long history of environmental activism and recent exposure to extreme weather, combatting climate change is a high-priority issue.

Unlike concerns that can be resolved through local collective action, such as self-help campaigns to build schools absent state intervention, climate change mitigation and adaptation also require policy responses. At the national level, Kenyans mobilize to demand global trade policies and regulations that combat climate change. When Kenyan president Uhuru Kenyatta faced pressure from the oil and plastics industry to remove the country’s ban on importing plastic waste from the United States and other countries in 2020, engaged citizens countered with domestic political pressure (Tabuchi, Corkery, and Mureithi et al. Reference Tabuchi, Corkery and Mureithi2020). Kenyans also mobilize at the local level, in part because environmental problems vary within the country. For example, drought-induced losses of livestock and crops are top concerns for climate change mitigation and adaptation in rural areas, but urban citizens may prioritize improved waste management and infrastructure to protect against cholera outbreaks (Moser et al. Reference Moser, Norton, Stein and Georgieva2010). Even within rural areas, the interests of underrepresented groups such as pastoralists diverge from those of citizens practicing settled agriculture. When marginalized populations are excluded from contentious policy processes, solutions risk neglecting the needs of impacted populations. Thus, climate change is a critical issue for understanding how membership in marginalized communities shapes expectations of systemic responses, and, ultimately, policy design.

Muslim Marginalization in Kenya

In 2007, then-presidential candidate Raila Odinga promised to initiate “deliberate policies and programmes to redress historical, current and structural marginalisation and injustices on Muslims in Kenya” in a signed a memorandum of understanding with the National Muslim Leaders Forum (NAMLEF).Footnote 5 As this document reveals, the historical and contemporary experience of marginalization is understood and discussed among Kenyan Muslims. In recent years, the state’s “terrorism policy,” responding to international pressure for counterterrorism, has intensified discrimination against Muslims (Barkan Reference Barkan2004; Mogire and Mkutu Agade Reference Mogire and Agade2011). Yet this policy is a continuation of a long history of Muslim marginalization and underrepresentation (Elischer Reference Elischer2019; Ndzovu Reference Ndzovu2014; Oded Reference Oded2000; Vittori, Bremmer, and Vittori Reference Vittori, Bremer and Vittori2009).

Muslims in Kenya are a large minority group that traverses divides impacting political representation and power, including geography and ethnicity. They represent between 10% and 20% of the population;Footnote 6 as Ndzovu (Reference Ndzovu2014, 8-9) describes, such statistics themselves are a point of contention, with Muslim leaders accusing the state of underrepresenting their communities in the census. While Muslims live throughout the country, they are more highly concentrated in the Northeast and Coastal regions and in Nairobi. The Kenyan Muslim political identity features “a sociocultural heterogeneity that cuts across” race and ethnicity (Ndzovu Reference Ndzovu2014, 7). Half of Kenya’s Muslims are ethnically Somali, producing a layered sense of exclusion based on ethnicity, religion, and contested citizenship; Muslims of Somali or Arab descent often face additional discrimination as “foreigners” (Ndzovu Reference Ndzovu2014, 117). Uniting them with Muslims from ethnic groups considered “Kenyan” is a shared history of marginalization.

Many Muslims believe that the state has targeted their communities and feel discriminated against when pursuing public jobs and education (Vittori, Bremmer, and Vittori Reference Vittori, Bremer and Vittori2009). Muslim-majority areas tend to receive more limited state infrastructure than other regions (Barkan Reference Barkan2004). In Nairobi, with an estimated 80 to 120 Muslim congregations, Muslims describe harassment and suspicion from state agents (Cussac and Goms Reference Cussac, Goms, Rodriguez-Torres and Charton-Bigot2010, 253). A report from the Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission of Kenya (Reference Truth2008) found that Muslim Kenyans often face excessive vetting and difficulty or denials in obtaining identity cards and passports, affecting access to public services like schooling. In the Muslim-majority Northeast Province, the government has frozen access to identification cards due to concerns about “foreigners” accessing them (Ndzovu Reference Ndzovu2014, 4).

These experiences are exacerbated by a sense of exclusion from political power. At independence, Christian missionary education was the pathway to political and administrative office (Cussac and Goms Reference Cussac, Goms, Rodriguez-Torres and Charton-Bigot2010). It was not until 1982 that a Muslim was appointed to a ministerial position, when a failed coup forced President Moi “to reconsider his cultivated antipathy towards Muslims” (Bakari Reference Bakari2013, 17). During the transition to multi-party elections, the government sought to suppress the nascent Islamic Party of Kenya (IPK) (Aronson Reference Aronson2013; Vittori, Bremmer, and Vittori Reference Vittori, Bremer and Vittori2009).Footnote 7 More recently, (Christian) prime minister Raila Odinga’s failed collaboration with Muslim constituencies during his presidential run, such as the memorandum of understanding described earlier, fueled skepticism about the possibilities for Muslims’ national policy engagement (Elischer Reference Elischer2019). Similarly, Chome’s interviews with Muslim activists revealed that debates over the inclusion of Kadi courts in the 2010 constitution, coupled with the experience of counterterrorism campaigns, contributed to a sense of “Muslim victimization” and heightened skepticism that “Muslim interests could be advanced through formal political processes” (Reference Chome2019, 548).

Diversity among Kenya’s Muslims also poses challenges to political organizing. For Ndzovu (Reference Ndzovu2014), internal ethnic and racial divides have weakened mobilization, despite a shared sense of marginalization. Elischer (Reference Elischer2019) argues that the geographic distance between Nairobi and the Muslim-majority Coast and Northeast regions further marginalizes Muslims in national politics. As Kresse (Reference Kresse2009) writes,

For coastal Muslims, life on the Kenyan periphery—vis-à-vis a state governed and administered by upcountry Christians—reflects the continuation of historical tensions between coast and upcountry (pwani and bara) which has also involved channels of serfdom and slavery (utumwa). (578)

In contrast, Christian churches have a long history of direct political engagement in Kenya. During one-party rule, the Anglican Church, the Catholic Church, and the Presbyterian Church of East Africa pushed for a democratic transition (Sabar-Friedman Reference Sabar-Friedman1997). More recently, Christian groups have been highly active on issues of sexuality and gender. Renewalist (i.e., Pentecostal and Charismatic) churches were key in pushing anti-LGBT policy across Africa, leveraging their mobilizational capacity to influence politicians (Dreier Reference Dreier2018; Grossman Reference Grossman2015). In 2019, Kenya’s Christian leaders rallied with Muslim leaders to thwart decriminalization of homosexual sex, and Kenya’s Supreme Court upheld the law in May 2019 (Ndiso Reference Ndiso2019).Footnote 8

This section has introduced the context in which our explanatory variable of interest—marginalization—is rooted. Muslims in Kenya perceive their position as one of marginalization, enduring from the colonial era to present day. We anticipate that membership in community institutions that perceive themselves as subject to “historical, current and structural marginalisation” (as cited at the start of this section) transforms how citizens see their own ability to impact change. Our central hypothesis is that

Muslims in Kenya will report lower perceptions of environmental efficacy due to their marginalized position within the state.

By studying a multi-ethnic religious group, we also gain insight into the potential impacts of ethnicity and religious doctrine on environmental efficacy. In the Kenyan context, much has been written about ethnicity, which politicians instrumentalize to drum up political support (Khadiagala Reference Khadiagala, Carothers and O’Donohue2019; Oyugi Reference Oyugi1997). However, we stress that marginalization is conceptually distinct from ethnic favoritism or disfavoritism, which changes with election cycles and shifting coalitions of power. We would not expect disfavoritism to have the same impact on efficacy as marginalization, which is structural and ongoing.Footnote 9 In centering religion, we join new work such as McClendon and Riedl (Reference McClendon and Riedl2019), Sperber and Hern (Reference Sperber and Hern2018), and McCauley (Reference McCauley2014) to stress the salience of religious identities in African politics; unlike these scholars, we foreground marginalization as the mechanism explaining religious impacts, rather than doctrine or practice.

Muslims’ attitudes toward the state and religious institutions provide further insight into the relationship between marginalization and efficacy. If marginalization impacts Muslims’ sense of environmental efficacy, we should see that general expressions of trust towards state actors condition the relationship between religion and efficacy. Similarly, if narratives within community institutions dampen efficacy, we would anticipate conditional effects of trust in religious leaders. In the following analyses, we examine expressions of trust in state and religious leaders as additional evidence of the relationship between marginalization, institutions, and environmental efficacy.

Methods and Data: Interviews, Focus Groups, and Surveys

We draw on qualitative and quantitative data to explore whether membership in marginalized community institutions impacts efficacy in the Kenyan context. Our key outcome of interest is citizens’ efficacy in relation to climate change, which we term “environmental efficacy.” While our theory draws on the concept of political efficacy more broadly, this measure exclusively captures one high salience political issue: climate change.

Our qualitative data come from exploratory fieldwork that examines how religious congregations and leaders discuss climate change, its causes and solutions, and their ability to respond to it. We conducted sixteen interviews with imams, priests, and pastors and nine focus groups with seventy-nine congregants in 2018.Footnote 10 Interviews and focus groups were conducted in English or Swahili (with the help of a translator), recorded, and transcribed. Each transcript was then coded for key themes, using a combination of a deductive coding guide and inductive identification of key subtopics within larger topics. The questionnaire focused on religious groups’ responses to climate change and did not prompt for experiences of marginalization.

Congregations were selected at three sites, capturing varying levels of urbanization, socioeconomic status, and religious demographics. It was important to include both urban and rural field sites, as experiences of climate change and religious dynamics vary between urban and rural areas. Within the capital, we selected two sites to capture socioeconomic variation: Central Nairobi and Dandora. Our Central Nairobi sample includes the middle-class neighborhoods or “estates” of Westlands and Kileleshwa. Dandora is a poor, densely populated settlement on the outskirts of Nairobi County, home to Nairobi’s largest landfill. Our third site is the county of Kilifi, a rural and predominantly Muslim county in the former Coast Province area, complementing the Christian majority demographics of the other two field sites.Footnote 11 Refer to the online appendix for further details on the qualitative data collection.

Our quantitative analysis relies on the Round 7 Afrobarometer survey of 1,599 Kenyans in 2016. The Afrobarometer is the only nationally representative survey administered in many African countries that includes information on political attitudes, behaviors, and demographics. Our reliance on this questionnaire limits our ability to fully measure some key concepts of interest. For instance, this round does not include questions that disaggregate internal and external efficacy, nor can we explore Sunni versus Shi’a religious affiliation or membership in certain Christian denominations. However, as described earlier, scholars have convincingly argued that Muslims widely share the experience of marginalization in Kenya. For the first investigation of whether membership in marginalized community institutions impacts efficacy in the Kenyan context, the Afrobarometer provides meaningful insights.

Our main outcome variable, environmental efficacy, comes from a multistage question about climate change. First, interviewers asked, “Do you think that climate change needs to be stopped?” Of respondents receiving the question, 21% said that climate change did not need to be stopped, and another 9% of responses were missing/don’t know.Footnote 12 Second, the remaining 70% who thought climate change should be stopped were asked, “How much do you think that ordinary Kenyans can do to stop climate change?” Response options were that “ordinary Kenyans” could “do nothing at all,” “do a little bit,” and “do a lot.” We recode responses to create an ordinal variable in which “nothing” is 0, “a little” is 1, and “a lot” is 2. We rely on these attitudes about the agency of “ordinary Kenyans” as our measure of environmental efficacy. Refer to the online appendix for additional information on variable coding.

Results

Religious Identity and Environmental Efficacy

Overall, Afrobarometer respondents in Kenya felt empowered to address climate change. Among those who said that climate change should be stopped, only 19% believed that ordinary citizens could do “nothing at all,” while 46% were optimistic that ordinary citizens could do “a lot.” As we show in the online appendix, Kenyans are among the most environmentally efficacious citizens on the African continent. This sense of efficacy is the outcome of interest in the analyses that follow.

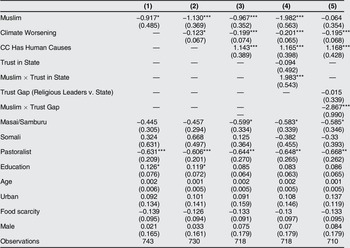

Figure 1 examines agency beliefs across religious groups.Footnote 13 In multivariate analysis, non-religious and Christian respondents are predicted to have identical levels of agency: nearly half said that ordinary Kenyans could do a lot to impact climate change, and about one-third thought they could do nothing. Muslims, however, stand out from other groups. In bivariate analysis without controls, only 13% of Muslim respondents reported high agency in relation to climate change, and nearly half (48%) said they could do nothing. Some of this gap, however, is due to covarying traits such as education and rural residence; as figure 1 shows, the gap is smaller in multivariate analysis. Still, even after controlling for a wide range of demographics, Muslims are predicted to be twice as likely as other groups to say that they could do “nothing” about climate change, and half as likely to say that they could do “a lot.”

Figure 1 Environmental efficacy, by religious affiliation

Note: 90% confidence intervals shown; estimates from Model 1. Source: Afrobarometer Round 7, 2016.

The remainder of the paper seeks to explain this difference. First, we present evidence that Muslim leaders and congregants are more likely to describe an unresponsive state than members of other major religious institutions in Kenya. Second, we show that citizens’ relationships with the state and religious leaders condition their sense of agency—but only among Muslims. In the final three sub-sections, we consider a series of other possible explanations: that religious differences are a spurious result of ethnicity or pastoralism, or that differences in Muslims’ beliefs about the causes of climate change or their attitudes about its salience explain Muslims’ lower efficacy. However, none of the alternative explanations adequately explains the efficacy gap.

Narratives of State Marginalization and Efficacy

Perceived oppression and state neglect, we argue, erode Kenyan Muslims’ sense of environmental efficacy, as individuals rationally expect the state to stymie their activism. Our Muslim focus group participants eloquently expressed this view. While many saw politicians as deliberately indifferent to their problems, describing them as “elusive,” “not dependable,” and there for “their own benefits,” others referenced active hostility to collective action. One respondent supported his claim that state actors could not be relied upon to address climate change by alluding to a recent protest, saying “they go and throw tear-gas on kids that are studying … so it means the politicians cannot help.”

Moreover, Muslims experience marginalization not simply as atomized individuals. Instead, religious communities internally communicate, disseminate, and reinforce members’ senses of marginalization, as well as their perceptions of the likely inefficacy of potential mobilization. Every Muslim leader we interviewed expressed alienation and distance from politicians; this was a constant across ethnic groups and locations in urban Nairobi or rural Kilifi. As one imam explained, “when you see politicians, it is when they are campaigning, they are looking for votes, but about your lifestyles, about what is affecting your safety, they are not there and they will never be there, not in Kenya.” Another imam reported that:

The ways in which we are able to communicate to them becomes a problem … because most of the time finding them is not easy and most of the time there is a very big gap between the political and religious leaders except for the time they need prayers only; when someone wants to be sworn in as president you are called to pray for them but other times you can’t find them. Politicians, we can use them only the time when they come to the church or mosque.

Catholic and Pentecostal leaders expressed comparatively strong ties to politicians. In direct contrast with the imam who described the difficulty of contacting politicians, a Pentecostal pastor in Dandora reported that “we have our MCA [Member of County Assembly] here, so approaching him is not difficult since he is in the area. Even their bouncers when you meet them you can tell them so that they take the message to him/her.” A pastor in rural Kilifi explained,

You see the church as an organization is not just independent, it works in the nations and in the countries where the governments do also work. So the church has a percentage of contribution to help the community to have good life and the government is also concerned in the provision of good life of the community, so what I think is that it’s good that they work hand in hand.

As these quotes hint, differing access to the state appeared to affect the perceived feasibility of environmental action. In our interviews, Christian clergy reported organizing activism and contacting politicians. One Catholic leader had recently convened a dinner bringing local chiefs, county assembly members, and other politicians together to discuss how to address the local dumpsite. Several priests thought that the church was an influential partner with the government in addressing climate change. Similarly, Pentecostal leaders described initiatives and workshops coordinating religious groups, NGOs, and government entities to address the issue. Christian leaders in the heavily Muslim (and geographically peripheral) Kilifi area expressed similarly high linkages to state politicians as those based in the capital city.

Historical discrimination and exclusion appear to inhibit such activities among Muslims. All clergy, including imams, said they talked about climate change with congregants. For example, one imam reported using “words of urgency” to discuss environmental issues in sermons. Another imam explained that “we should not wait for another Wangari Maathai, actually everybody should be Wangari Maathai, we should do everything and we should pray as well.” However, Muslim focus group participants were less likely than members of other groups to believe the government would respond. For example, “there are challenges as our discussions are not getting any support from the government, both national and county, yet they are supposed to be the implementers.” A second participant complained that “our religious leaders talk often about these changes but they too get to a point they still need the implementers, the government. So we go back to depending on the government.” While Muslims saw the government as necessary for climate change solutions, such that “the common citizen can’t do anything because there is a stage he gets to where it is the responsibility of the government,” others expressed the futility of a state response: “we should not bother ourselves with engaging politicians.”

By contrast, respondents in the Christian focus groups articulated far greater expectations that it was possible to collaborate with the government to impact climate change. For example, one Pentecostal congregant argued that “the church should partner with the politicians … because politicians have a lot of influence in our community and so does the church so with these two coming together then we can work together to make our environment better.” One respondent explicitly described her expectations of governmental responsiveness:

I think the government listens to the Catholic Church, I do believe that Catholic Church in a country is like another government so, I think if the Catholic Church decides that their leaders and their priests decide we need to do something to our environment I think our government will listen, our politicians will listen, of which most of our politicians are Catholics. I think through that way it would be easier.

Overall, these interviews revealed that members of different institutions diverged widely in belief that they could effect environmental policy change in connection with state actors.

The Conditioning Effects of Trust on Kenyan Muslims’ Efficacy

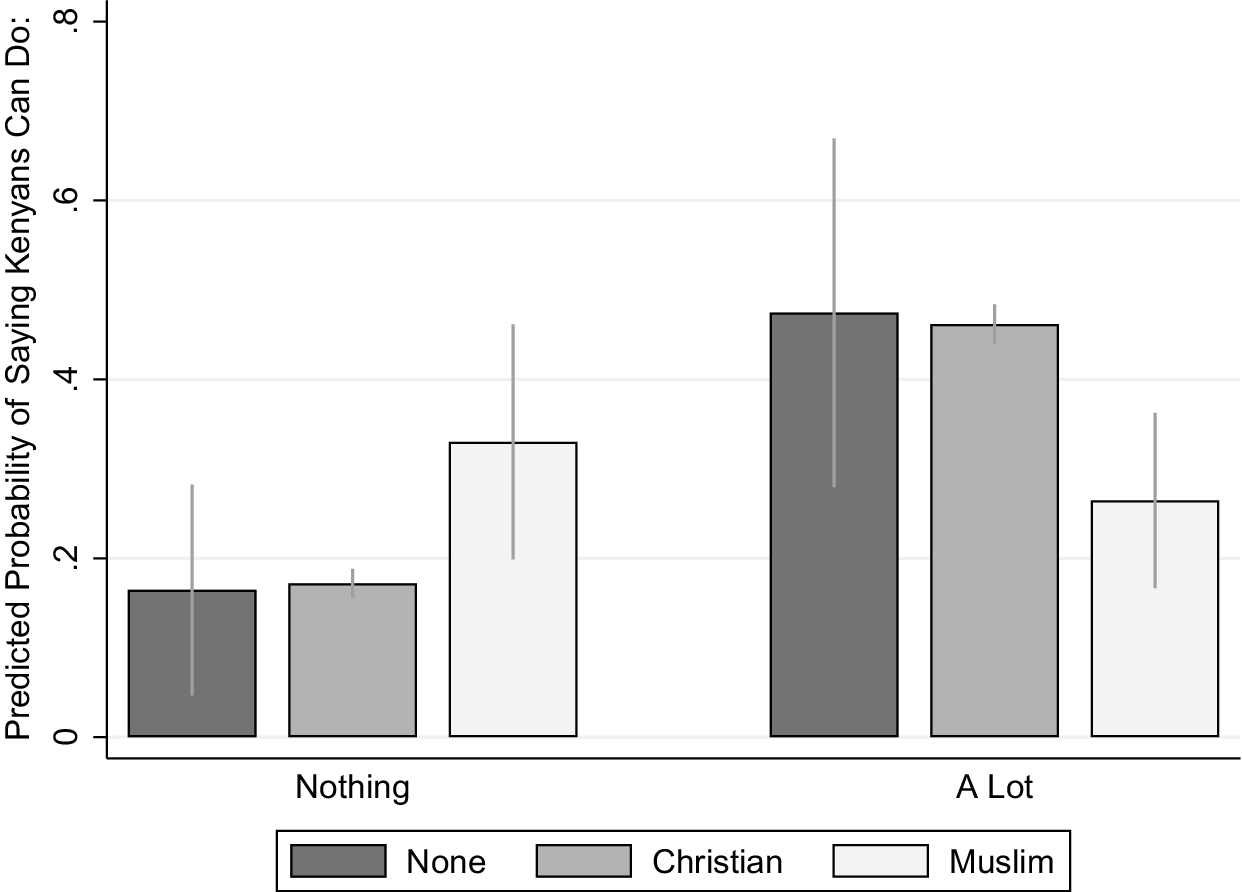

Our quantitative analysis provides further evidence supporting the marginalization theory: views of the state and religious leaders help to explain Muslims’ lower efficacy. The analysis presented in Model 4 of table 1 and figure 2 reveals that trust in state institutions shapes Kenyan Muslims’ sense of their own efficacy to make a difference on climate change. This indicates that the individual’s relationship with the state impacts the link between religion and environmental efficacy. This is particularly meaningful evidence in favor of the marginalization argument, given that our measure of environmental efficacy does not prompt for perceptions of governmental responsiveness.Footnote 14 The analysis shows that moving from the minimum to the maximum level of trust in the state raises Muslims’ predicted probability of reporting high environmental efficacy from .12 to .45, and it is associated with a drop in the probability of reporting low efficacy from .54 to .17. However, attitudes toward the state only matter for Muslims. Group histories of marginalization have made the state salient as a potential limiting force constraining Muslims’ political participation. By contrast, environmental efficacy is not linked to state trust in religious groups without a history of marginalization. As a result, the gap in efficacy between Muslim and non-Muslim respondents is limited to citizens who distrust state leaders; there is no efficacy gap among citizens with high trust in state leaders.

Figure 2 Trust in state leaders boosts environmental efficacy among Muslims

Source: Afrobarometer Round 7, 2016

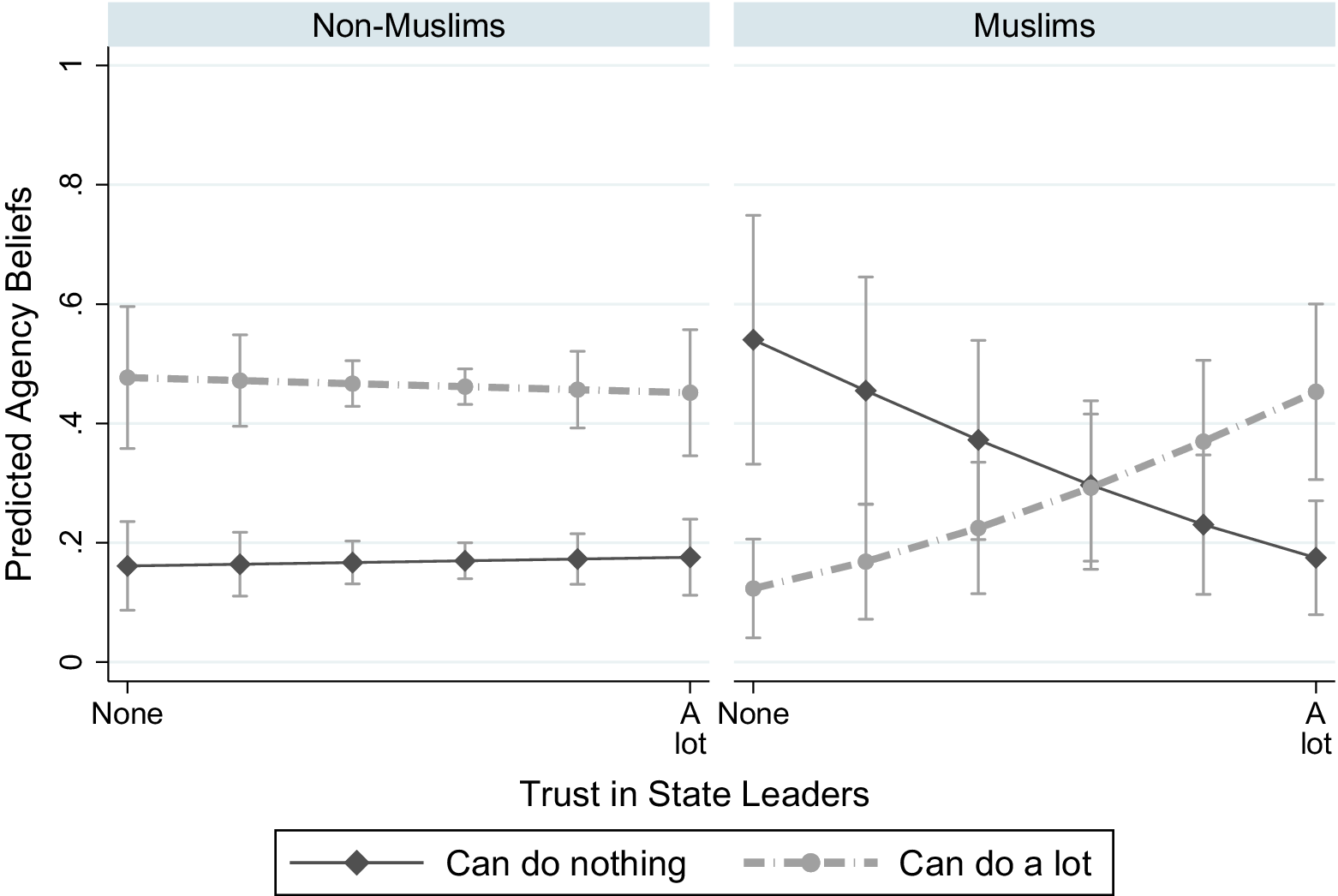

Table 1 Determinants of environmental efficacy

Notes: Results from ordinal logistic regression models clustered on region. Regional fixed effects and logistic regression cutpoints not shown; standard errors in parentheses.* p < .10, ** p < .05, *** p < .01

Source: Afrobarometer Round 7, 2016

Ties to community institutions also affect efficacy within marginalized groups. A series of models in the online appendix show that trust in religious leaders conditions the impact of religious affiliation on efficacy. Muslims who strongly trust their religious leaders report substantially lower efficacy to address climate change than do Muslims who are weakly tied to the hierarchy within their religious communities. In these survey data, we do not have evidence for the mechanism; Muslim leaders might socialize their communities via collective narratives of marginalization that compound feelings of low efficacy, or the types of Muslims who trust religious leaders might have low efficacy. Nonetheless, our qualitative evidence provides strong indications that Muslim communities widely share and discuss a feeling of disconnection from the state that stymies efficacy and activism. Similarly, other scholars observe that Muslim leaders explicitly discourage political engagement in response to marginalization; Chome, for instance, found that some sermons included “religious justifications for Muslim disengagement with the formal political process” (Reference Chome2019, 549).

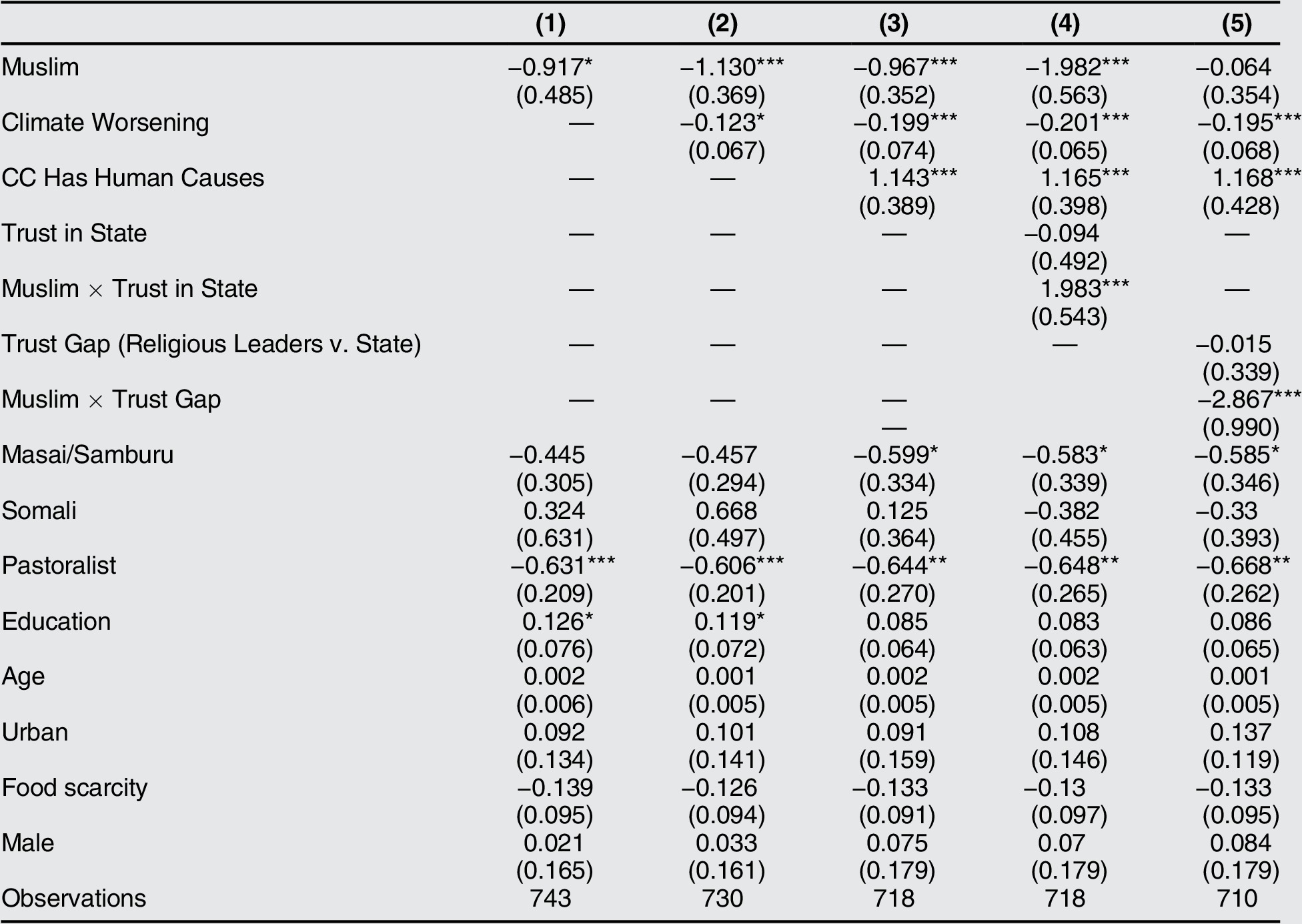

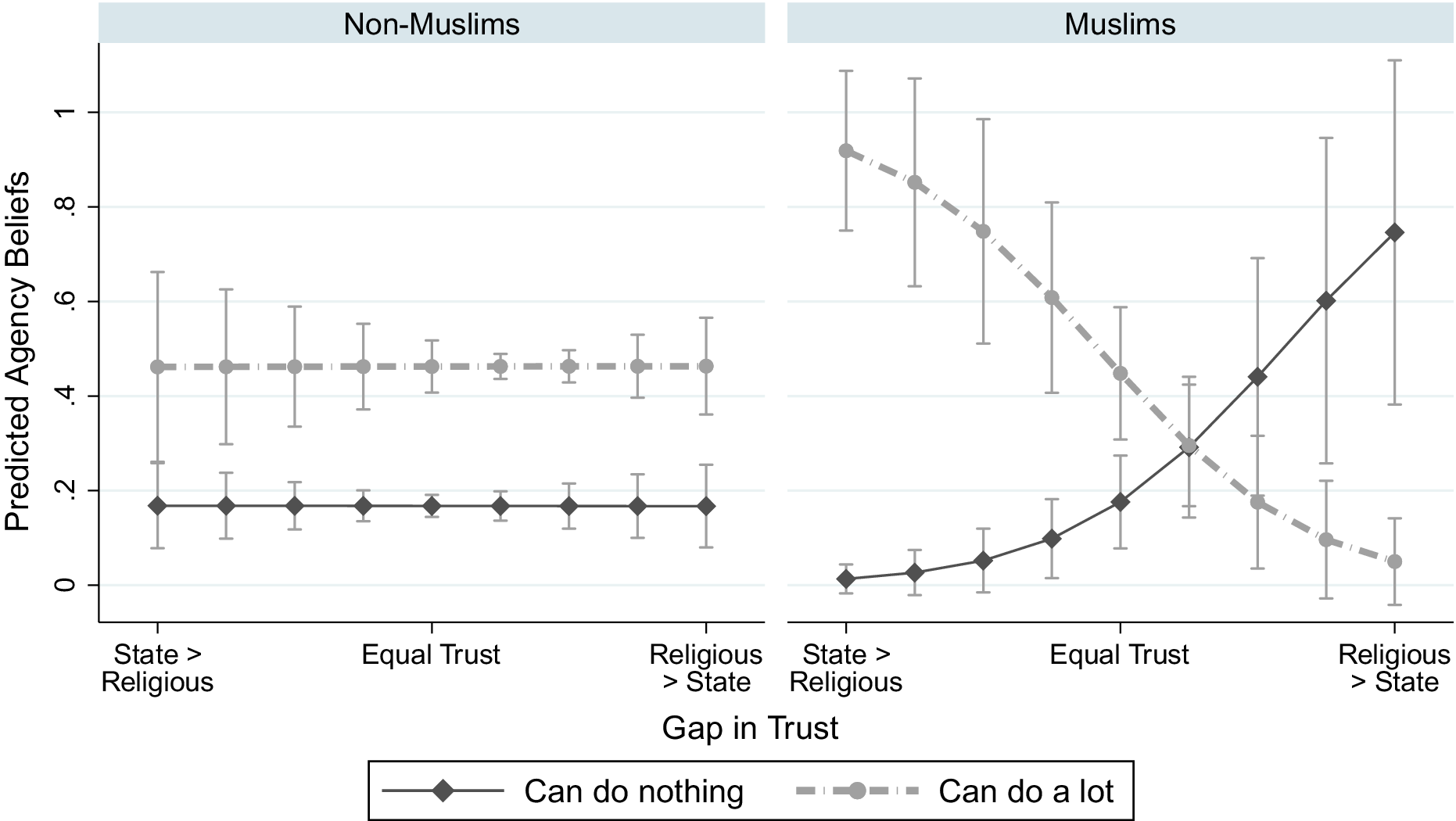

In Model 5 of table 1 and figure 3, we introduce a measure of the gap between trust in state and in religious leaders. This gap is extremely predictive of environmental efficacy; among Muslims who trust religious leaders much more than state leaders, the predicted likelihood of saying that “nothing” can be done is .75, and that of saying that “a lot” can be done is only .05. Among Muslims who trust state leaders much more than religious leaders, by contrast, the equivalent predicted likelihoods are inverted, at .01 and .92. Such ties have no impact on the attitudes of non-Muslim Kenyans. These results indicate that alienation from the state and ties to community institutions both impact the efficacy of Muslim citizens.Footnote 15

Figure 3 The gap in trust between religious and state leaders reduces environmental efficacy among Muslims

Source: Afrobarometer Round 7, 2016

Do Ethnic or Other Identities Explain the Efficacy Gap?

An alternative explanation is that the correlation between religious affiliation and efficacy might stem from underlying differences among ethnic groups. Ethnicity and religion are intertwined in Kenya; 65% of Muslims in our Afrobarometer sample are Somali. This ethnic group may well report lower efficacy, given the Kenyan state’s responses to al-Shabaab attacks and accusations of “foreignness.”Footnote 16 Hence, our analysis presented in figure 1 includes indicator variables for identification as Somali or as Masai and Samburu. The latter two ethnic groups were historically semi-nomadic, giving them a unique status within the state that could potentially impact efficacy.

Table 2 in the online appendix presents a series of robustness checks further exploring the role of ethnicity. Model 1 in that table show that Muslims have significantly lower environmental efficacy, even controlling for a long list of other ethnic groups. Model 2 accounts for ethnic grievances, based on a question asking “how often, if ever” the respondent’s ethnic group was “treated unfairly by the government”; this control does not significantly change the effect of Muslim on efficacy. Finally, Model 3 adds an ethnic salience variable to the baseline model as a third check for a potentially confounding impact of ethnicity, based on a question asking whether the respondent would identify as Kenyan or a member of their ethnic group if they “had to choose.” All three models increase our confidence that something about Muslims’ experiences in Kenya reduces their efficacy, independently of ethnicity.

Our qualitative data support the conclusion that the association between religion and environmental efficacy is not simply a spurious result of ethnicity. In our rural Kilifi sample, respondents from the same ethnic group (Mijikenda) but different religious communities (Pentecostal and Muslim) expressed markedly distinct expectations of responsiveness from politicians. The two Pentecostal pastors both described collaborative relationships with the state. One detailed a joint effort in which the church mobilizes labor for an environmental campaign funded by the government. In stark contrast, Muslim leaders and congregants could not envisage such collaboration. As one imam in Kilifi put it succinctly: “No politician will listen to you.” In Central Nairobi and Dandora, our Muslim focus groups were ethnically mixed, including a small number of ethnic-Somalis, yet there were no systematic differences in expectations of government responsiveness and environmental efficacy across the Muslim samples. The qualitative data reveal that Muslims share the perception of a non-responsive state; it is not unique to any ethnic group or region.

Our models also consider the role of pastoralism. Pastoralists are highly exposed to climate change, as decreases in water and viable grazing land force them to move to provide for livestock. Analysis in the online appendix shows that pastoralists are significantly more concerned about climate change than other groups. Moreover, in Kenya and globally, pastoralists have had contentious relationships with the state, and a semi-nomadic livelihood inhibits organizing (Azarya Reference Azarya1996; Kituyi Reference Kituyi1985). For all these reasons, it is little surprise that pastoralists express significantly lower environmental efficacy than other groups (refer to table 1). However, pastoralism does not explain the significant effect of Muslim affiliation on efficacy.

Do Beliefs about the Causes of Climate Change Explain the Efficacy Gap?

A second alternative explanation for religious differences in environmental efficacy relates to doctrinally rooted scientific beliefs. The question of whether climate change is anthropogenic or instead results from natural—or even supernatural—processes is a central divide in public opinion on the environment. It stands to reason that people would be skeptical of their power to solve a problem perceived as natural or divine in origin. Religious teachings contain wide-ranging propositions about the nature of the material world, and the role of supernatural forces in the weather. It seems plausible that Kenyan Muslims might share ontological approaches to humans’ role in climate change—beliefs that influence perceptions of environmental agency.

However, we find little evidence of such religious differences. In the Afrobarometer, 61% of respondents saw human behavior as the sole cause of climate change, and another 14% attributed climate change to both human and natural causes; just 25% attributed it to natural processes or other factors. There are no statistically significant differences between Christians, Muslims, and the non-religious in such beliefs (refer to the online appendix).Footnote 17 Qualitative fieldwork confirms the absence of religious differences in causal attributions. Across religious groups, clergy provided strikingly consistent explanations of climate change. Every leader interviewed reported that changing weather resulted from human behavior, including phenomena such as charcoal burning, deforestation, and air pollution. Some clergy did also reference more distal behaviors, such as lack of prayer; sexual sin and deforestation were discussed together seamlessly, as joint causal factors. As one imam described, “the teachings of science and religion are not far off, I think they relate closely.” In addition, none of the clergy thought climate change was a result of a natural process of change over time.

In sum, religious differences in causal attributions are small and cannot explain differing environmental agency across religious groups. Indeed, controlling for the perception that climate change is anthropogenic in our model of efficacy does not reduce the size or the statistical significance of Muslim religious affiliation—despite the fact that belief in the human origin of climate change is, as we speculated, a highly statistically significant predictor of efficacy (refer to table 1, model 3). Belief that climate change is anthropogenic raises the predicted probability of reporting high environmental efficacy from .26 to .50.

Does Issue Salience Explain the Efficacy Gap?

Climate change might affect Muslims more severely than members of other groups—perhaps due to Muslims’ concentration in certain geographic areas, or in certain occupations. Actually experiencing climate change might sap one’s sense of efficacy. However, empirical analysis reveals two key findings. First, after controlling for differences in region and material circumstances, there are no interreligious differences in issue salience. Second, controlling for issue salience increases the estimated Muslim/non-Muslim gap in environmental efficacy.

In general, Kenyans are quite concerned about climate change. In 2016, 56% of the sample reported that the climate had gotten worse in the past decade. In addition, 15% mentioned a climate-related issue as the most important problem for the government to address, and 38% mentioned it as one of the three most important problems. In qualitative interviews, religious leaders unanimously agreed, as did participants in eight of nine focus groups, that the weather was changing, interpreted as part of a broader pattern.Footnote 18 They supported their beliefs with examples of extreme weather and environmental changes, including unpredictable rainy seasons and extreme temperatures, drought, flooding, and decreases in harvests and fish stocks.

In a bivariate analysis of the Afrobarometer, environmental concern is higher among Muslims than other groups. However, this appears entirely to be the result of covarying traits. Kenyan Muslims cluster in the Northeast and Coast provinces, which have been highly affected by severe weather. For example, a drought in 2005–2006 caused a 70% decrease in the size of herds in Northern Kenya, leading pastoralists, including many Muslims, to become heavily reliant on international aid (Baird Reference Baird2008, 4). In addition, Muslim religious affiliation is correlated with formal education, poverty, and rural livelihoods—all of which may impact issue salience. In multivariate models, religious affiliation is uncorrelated with both environmental concern and belief that climate change needs to be stopped (refer to the online appendix); religious differences are due entirely to Muslims’ concentration in regions highly affected by climate change.

Model 2 in table 1 considers the relationship between religious affiliation and efficacy, controlling for beliefs that the climate is worsening. Strikingly, after we account for the salience of climate change, the gap in efficacy between Muslims and non-Muslims grows. The predicted gap in saying that “ordinary Kenyans” can do nothing widens to 21 percentage points, and the gap in saying that they can do a lot widens to 24 percentage points. Different perceptions of the changing climate are not the source of lower efficacy among Muslims in Kenya. Instead, the qualitative and quantitative data indicate that marginalization generates systematic differences in how members of religious institutions evaluate their ability to impact climate change.

Discussion and Conclusions

Efficacy links interests to action—yet poor treatment by the state severs that link. Policies marginalizing communities thus impact political engagement over the long term. However, these effects are not automatic; community institutions shape the relationship between marginalization and agency. Though theories of political efficacy tend to treat social networks as a resource that boosts efficacy, networks reinforcing narratives of marginalization should yield the opposite outcome.

Insights gleaned from interviews in Kenya elucidate the argument: Muslim community institutions reinforced a narrative of members’ incapacity to effect change. Leaders emphasized that politicians would not respond to their demands, rendering collective action for policy change ineffective; congregants echoed those assessments. Thus, focus groups with Muslims captured pieces of a continuing conversation within the community about discrimination and the limits of agency. By contrast, while it would be a grave mistake to suggest that non-Muslim Kenyans are highly trusting of state institutions, leaders and members of Christian community institutions expressed systematically higher expectations of state responsiveness than did Muslims.

Quantitative analysis bolsters our conclusions. Muslim citizens expressed lower efficacy than other groups—a relationship that cannot be attributed to differences in education, wealth, ethnicity, or region, nor to issue salience or beliefs about the causes of climate change. Instead, Muslims’ reduced efficacy is a function of their relationships to the state and religious leaders. That the conditional effects are unique to Muslims suggests the importance of community institutions as a forum where marginalized citizens learn what to expect of the state. Despite a vast literature on collective identity and political behavior in Africa, this is, to our knowledge, the first empirical study of collective marginalization and efficacy in the African context.

These findings also have implications for climate change policy. First—in striking contrast with the United States (Guth et al. Reference Guth, Green, Kellstedt and Smidt1995)—we find no religious differences in climate change beliefs in Kenya. Nearly all religious leaders and focus group respondents thought that climate change was an important issue, one with human causes and solutions. After accounting for regional differences, religious groups prioritized climate change equally. Our results echo work elsewhere that uncovers no religious differences in these beliefs in Latin America (Smith and Veldman Reference Smith and Veldman2020). Moreover, the findings are consistent with studies that identify climate change as a high priority among Muslims in Turkey, Indonesia, the Palestinian territories, and Nigeria (Lewis, Palm, and Feng Reference Lewis, Palm and Feng2019). Yet in other contexts, membership in Muslim religious institutions may actually increase environmental efficacy (e.g., Amri Reference Amri, Veldman, Szasz and Haluza-DeLay2013). Against the backdrop of prior findings, our results indicate that a religious institution’s relationship with state and political power—a product of a specific political context—is highly consequential for citizen climate activism.

Second, our analysis suggests that groups that are highly concerned about climate change may remain on the sidelines due to experiences of marginalization. Cross-nationally, countries that are most affected by climate change are also least able to prevent it. This study demonstrates a similar phenomenon on a sub-national level: respondents for whom climate change was most salient felt least efficacious addressing it. In addition to the Muslim minority, we also observe this result in the plight of pastoralists, who are highly impacted by drought and climate instability, but were significantly less likely than other respondents to say that they could effect change. If the most vulnerable populations are less likely to organize collective action, climate change policy is unlikely to respond to their specific needs. This further reinforces their real and perceived exclusion from the processes of addressing climate change. Consequently, these findings provide a lesson to policymakers: in designing climate change policy, it is critical to identify citizens who may be systematically less likely to engage. Mitigating climate change requires mitigating the effects of marginalization.

Supplemental Materials

1. Environmental Efficacy in Kenya in Comparative Context

2. Qualitative Research Design

3. Variable Coding for the Afrobarometer Analysis

4. Robustness Checks and Additional Statistical Analyses

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S153759272000479X.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Paul Djupe, Calla Hummel, Ned Littlefield, John McCauley, Liz Sperber, Scott Strauss, seminar participants at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, audiences at the 2019 American Political Science Association and African Studies Association Annual Meetings, and anonymous reviewers for both Perspectives on Politics and the Kellogg Institute’s Working Paper Series for helpful comments on prior versions of this paper. Mercy Ngao and Melda Munyazi provided excellent research assistance in Kenya. The British Institute in Eastern Africa provided institutional support. This research was funded by a Project Launch Grant from the Global Religion Research Initiative of the University of Notre Dame. The research was reviewed by the IRBs of Iowa State University and Boston College, and was cleared by the National Commission for Science, Technology & Innovation in Kenya.