Introduction

In the last decade, Azerbaijani universities’ upward implementation of English-medium instruction (EMI) policy has spread among most of the country's universities, public and private. Students are no longer enthusiastic about getting an education in their native language, neither they see Russian as a medium of instruction that used to be a vehicle for a brighter future. Research suggests that the rapid implementation of EMI policy is primarily motivated by the pursuit of internationalization (Williams, Reference Williams2023), participation in international projects (Mammadova, Reference Mammadova2020), and international academic mobility (Mammadova, Reference Mammadova2023). As a result, attributed to the mass abandoning of the country by young early career specialists who have recently graduated from Higher Educational Institutions (HEI), the country annually loses a high number of qualified personnel (see Figure 1) who heavily resort to their linguistic competencies and go after a ‘better life’. Figure 1 demonstrates the average value for Azerbaijan to leave the country during the period between 2015 and 2022. With an average of 4.74 points out of 10, the minimum 4 index point was observed in 2016 and a maximum of 4.4 index points in 2022. In turn, the UN Migrant Stocks (2021) reports that by mid-2020 Azerbaijan had an emigration rate of 10.6 percent of its entire population. According to Chaikhana Media (2022), ‘there's a brain drain in Azerbaijan, highly-skilled people do leave their country even though they have had a high salary in Azerbaijan.’

Figure 1. Early career specialists who left the country between 2015-2022 (The Global Economy website: https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Azerbaijan/human_flight_brain_drain_index/)

It should be pointed out that in the 1990s, because of the lack of jobs and unemployment issues, Azerbaijanis migrated to Russia and other CIS (Commonwealth of Independent States) countries, but since 2010, there has been a new trend. The nature of migration from Azerbaijan has changed. Namely, while previously rural residents were moving to Russia, now people from Baku and other large cities, as well as qualified young people, are leaving for Europe (OC Media, Reference OC2017). This is because a lot of Azerbaijanis got a chance to study abroad, and as a result, stay there. Thus, although there are few official statistics about emigration from Azerbaijan, international studies show there has been a steady increase over the past few years (Chaikhana Media, 2022).

Having referred to a number of recent publications, the paper aims to explain the correlation between the EMI and the mass outflow of young specialists to the countries favorable for international academic and work environments open to the use of English as a Lingua Franca (ELF). The research questions set for this paper are: What is the present-day role and position of the English language in Azerbaijan? What are the key implications for EMI in Azerbaijani Higher Education? How does EMI correlate with the brain drain that has been intensified within the last six to eight years?

The present-day role of the English language in Azerbaijan

English language teaching has always been a part of the local curriculum in secondary Azerbaijani schools and universities. A particular rise of interest in the English language was witnessed in the 1990s, just after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when each member state shaped a new path of its existence. The development of English as a key foreign language is well described in the paper by Mammadov and Mammadova (Reference Mammadov and Mammadova2022), who walk the reader through the last 30 years, from the 1990s to the present day. According to the authors, the promotion of linguistic diversity and the spread of the English language on the territory of Azerbaijan early in the 1990s is mainly attributed to the role of the three major Pan-European institutions: The European Union, Council of Europe, and the Organization for Security in Europe (OSCE). The collaboration of locals with these organizations made them learn and use English as a language of international communication. A further enhancement and promotion of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) in private and public schools as well as in higher educational institutions was due to the internationalization of the educational system which took place between 1990 and 2000. These processes were later followed by a number of other important events in the educational developments in Azerbaijan such as accession to the Bologna process (May 2006) and commitment to the goals of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA), as well as the adoption of the Joint Convention of the European Council and UNESCO on Recognition of Higher Education Qualifications and Documents (Lisbon, April 11, 1997; Bologna, June 19, 1999). In one of my book publications entitled Exploring English Language Teaching in post-Soviet Era Countries: Perspectives from Azerbaijan (2020), I also mentioned that after the collapse of the Soviet Union, English language teaching has become the central issue in curriculum design for modern education. While the dominance of the Russian language as a medium of external and internal communication was first substituted by the local language, which became a single state language of the country, English became the language of external communication, i.e., communication between the nations outside their local communities. In other words, the inclination of Azerbaijanis toward learning English rather than Russian or other foreign languages has also dramatically increased, which is supported by numerous recent studies (Shafiyeva & Kennedy, Reference Shafiyeva and Kennedy2010; Karimova, Reference Karimova2017; Mammadov & Mammadova, Reference Mammadov and Mammadova2022). So, today the unique role of English in Azerbaijan is a commonly accepted reality (Mammadov & Mammadova, Reference Mammadov and Mammadova2022). However, the establishment of English as a medium of instruction in most of the HEIs is a relatively new phenomenon.

EMI in Azerbaijani HEIs

A large-scale change in language curriculum took place with the Bologna Agreement signed by a number of countries that engaged in a new wave of educational reforms with the goal of bringing more coherence to the higher education system across Europe (Mammadova, Reference Mammadova2020). Azerbaijan committed itself to the Bologna process in 2006, which opened new horizons for local citizens in various academic fields within the country and overseas. By and large, the signing of the Bologna agreement could be considered a starting point for increasing academic exchange among the universities and their actors. With the intensification of academic mobility programs that drew large numbers of students, the teaching of English as a foreign language was deemed insufficient. Many universities have implemented English as a medium of instruction that allowed a transparent exchange of academic actors among HEIs. Moreover, the rising demand for English not only in education but also in the workplace made EFL insufficient in reaching the level of proficiency adequate to the requirements of the global market. Consequently, these demands for English language proficiency drove language policies in Azerbaijan towards implementing English as a medium of instruction (EMI) as well as enhancing the quality of language teaching and assessment (Mammadov & Mammadova, Reference Mammadov and Mammadova2022).

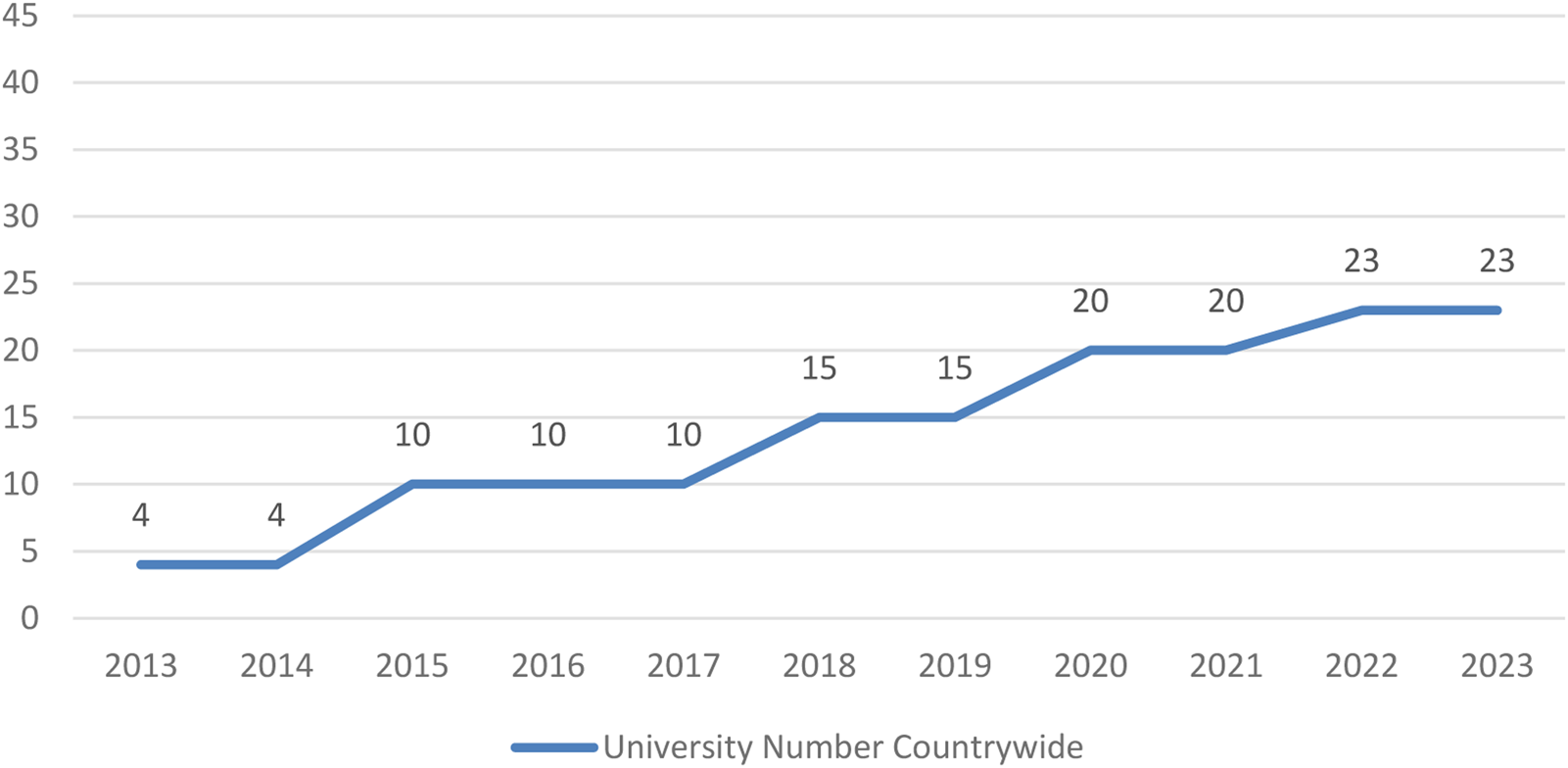

Today, universities in Azerbaijan fall under three main categories: Public Higher Education Institutions under the Ministry of Science and Education (the total number of universities is 20); Public Higher Education Institutions under other State Organizations (the total number of universities is 13); and Private Higher Education Institutions (the total number of universities is 11); overall, making 44 Higher Education Institutions. A study specifically conducted for this paper demonstrates that out of the mentioned universities, three of them are using no other language of instruction but English, and other 20 universities offer English as a medium of instruction (EMI) for most of their programs as an alternative option to the local Azerbaijani language, and/or Russian sometimes. If we compare the numbers with those collected by the British Council back in 2014, Azerbaijan was among the 38 percent of the focal countries where EMI was favored by the public (Dearden, Reference Dearden2014), while now, we observe the actual rise of universities which factually implement EMI up 53 percent. Based on the study conducted by Linn and Radjabzade (Reference Linn and Radjabzade2021), some data provided by the Ministry of Science and Education of the Azerbaijan Republic (https://edu.gov.az/en, 2022), and research specifically conducted by the author for this paper (2023), it became possible to create a graphical representation of gradual implementation of EMI by the local universities within 2013–2023. Figure 2 demonstrates the number of Azerbaijani universities (23 out of 44) that offered EMI in each academic year.

Figure 2. Number of universities offering EMI 2013–2023

To this end, the general public moods and the current situation in the country indicate the increasing interest of the nation to get an education in English.

Understanding the brain drain and its correlation with EMI

Back in 1974, Professor R. M. Kalra explained brain drain as a process of deliberate draining of developing countries’ professionals. The developed countries used the ‘free of charge’ skills of nationals whom developing countries had trained (Kalra, Reference Kalra1974). Today, with the globalization of education, this process does not seem as biased as before since most students now go overseas to be trained educationally and professionally. In other words, the more courses you have taken abroad, the more you in demand globally. As to the process of brain drain, its general causes are complex, and are by no means wholly economic in nature (Van der Kroef, Reference Van der Kroef1968). Among the most evident are attitudes and preferences in the nations, the limitations of domestic opportunities and development, and immigration and educational policies in countries-recipients. However, today the process of brain drain looks fairly natural compared to previous times, and this mainly depends on study-abroad opportunities. For instance, in the countries of the Asia and Pacific region, mobility programs are widely applied with the purpose to enhance global competence. Countries invest in education to enhance economic productivity; this, in turn, attracts and retains talent from all around the world that would enhance human capital, in particular, the productive wealth embodied in labor, skills and knowledge (Mok & Xiao, Reference Mok and Xiao2016: 369). Human capital is an intangible asset that includes knowledge, skills, and the experience of individuals (Becker, Reference Becker1993; as cited in Latukha et al., Reference Latukha, Shagalkina, Mitskevich and Strogetskaya2022: 2231). Increasing numbers of students continue to travel from low-income countries to study in developed countries, as governments of the sending countries weigh the economic, political, and cultural implications of global student mobility (Donovan Rasamoelison, Averett & Stifel, Reference Donovan Rasamoelison, Averett and Stifel2021: 3923). The rapid growth of studying abroad has inevitably raised the concerns of ‘brain drain’, in particular when students graduating from overseas universities decide not to return to their home country but stay in the foreign countries to pursue their careers and residence (Mok & Xiao, Reference Mok and Xiao2016: 370). One of the limiting factors of a brain drain during the Soviet times, especially to the European countries and countries outside the Union, was definitely the language barrier and the fear of communication breakdown in the countries where Russian was not a commonly accepted language. With the expansion of English in those territories, more people, particularly young ones, felt linguistically confident to travel abroad. And while English was rooted as a Lingua Franca (ELF) globally, there was more need for EMI in educational institutions. On the other hand, some scholars believe it is a fallacy that English-speaking countries have trade-link advantages because of the prominence of English as a global language. Melitz (Reference Melitz2008), for instance, found that despite the dominant position of English as a world language, it is no more effective at promoting trade than other major European Languages. He argues that literacy and knowing several other major European languages are more important in promoting trade (Donovan Rasamoelison et al., Reference Donovan Rasamoelison, Averett and Stifel2021: 3919). There is definitely no doubt that the global dominance of English does not diminish the importance of local languages; however, it remains and will remain a key linguistic vehicle and means of communication in non-English speaking countries unless a local language is grasped. With this in mind, HEIs expand the influence of EMI making it a starting linguistic point for students. Overall, the link between brain drain and EMI is obvious: while the dream of going abroad stimulates the interest in EMI, the implementation of EMI becomes a hope for students to go abroad.

English as a brain-drain catalyst in Azerbaijan: Or, do we deal with the ‘brain-bridging’?

Presently there are two main motivations influencing the brain drain in Azerbaijan: students seeking an education abroad, who may not return, and young professionals seeking better opportunities abroad (Walsh–Zamanbayova, Reference Walsh–Zamanbayova2023). Because Azerbaijan has currently put some policies in place, such as the establishment of local double-degree programs with prestigious international universities and the prerequisite of the government's study abroad (SA) scholarship, many students have a chance to leave their country. It should be noted that these policies do not foresee the implementation of any language among students other than English. Likewise, among all other languages, English remains the medium of instruction in the HE classes and the major language requirement to take part in any of these programs. That is why the popularity of international language testing exams such as TOEFL, IELTS, Duolingo and others is unprecedented among the students. Moreover, if we analyze the destination countries sponsored by the state government study abroad scholarship programs, English-speaking countries including the USA, the UK, Canada, and Australia occupy the first places in the list.

A clear link between English and the brain drain in Azerbaijan can be observed when comparing the figures from some 20 to 30 years ago to now. In 2012, Docquier and Rapoport introduced a table where they showed the outflow to various global regions from Azerbaijan, i.e. a country whose population varied between 2.5 and 10 million people losing around 1–2% of its population. During this time, i.e., within 10–15 years, 3,302 students studying Bachelor and Master of Science programs abroad were sponsored by the government. Compared to some other countries though, this number was relatively small, which mainly depended on a linguistic factor, i.e., the expansion of English at HEIs at that time was yet at its primitive level. With the rapid expansion of English within the last ten years, as well as the recent implementation of EMI programs in 23 universities in Azerbaijan, more and more students felt confident enough to leave the country. The numbers retrieved from the official website of the Ministry of Science and Education of the Republic of Azerbaijan (https://edu.gov.az/en) that represent the academic movement of Azerbaijani students within the last twenty-three years (2000–2023) are visualized in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Number of students obtaining study-abroad state scholarships, 2000–2023

Likewise, according to Linn and Radjabzade (Reference Linn and Radjabzade2021), the expansion of English and primarily EMI in Azerbaijan can be traced back to 2010, with EMI being widely integrated into the local curriculum from 2015. It should also be mentioned that both programs (EMI and SA) see international IELTS certification as a key condition to take part in. The development of EMI programs and the SA programs over a certain period of time (2013–2023) has been statistically calculated (out of the numbers presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3), and the ratio is represented in Figure 4.

Figure 4. The development of EMI & SA programs, 2013–2023

A percentage ratio calculated from the numbers in Figure 2 for the universities that have implemented EMI between 2013–2023 demonstrates a gradual increase with no cases of decline throughout the timeline. Likewise, the development of SA programs witnessed a stable increase between the years 2000–2015 (see Figure 3), with a drastic decline in percentage (see Figure 4) between the years 2016 and 2020, which has a solid justification. Since 2016, the number of students getting a state scholarship to study abroad has decreased while the brain drain has steadily increased (Walsh–Zamanbayova, Reference Walsh–Zamanbayova2023). This mainly originated in a sudden devaluation of the local currency when the dollar and euro simply doubled in price. This was a key trigger for the young generation to leave the country for a better life at their own expense. However, the process was later affected by two factors: the expansion of the COVID–19 pandemic, and an effective state policy to attract its young cadres to good positions. These two have resulted in a sudden shift of the course from a brain drain to a brain-bridging. Now, if we analyze the links and networks between non-returnees and the locals as the formation of transnational bridges, then the frequent interactions, transactions, and exchanges between them would generate additional resources and create other forms of transnational social and cultural capitals favorable for social, cultural, political and economic developments back home (Mok & Xiao, Reference Mok and Xiao2016: 371), and of course, English remains the key language of communication. As Mok and Xiao (Reference Mok and Xiao2016: 370) contend, students who choose to stay in foreign countries for work and residence may not necessarily be creating ‘brain drain’ problems but instead are creating new transnational resources that are conducive to development back home, as the whole scenario can be analyzed as ‘brain circulation’ or ‘brain bridging’. Donovan Rasamoelison et al. (Reference Donovan Rasamoelison, Averett and Stifel2021: 3925) contend that when investigating the different mechanisms through which student migrants can impact the growth of their home country, some evidence of ‘incentive effects’ for students going to English-speaking countries can be found. So, for 2022–2026, the government plans to sponsor up to 400 students a year to study undergraduate and postgraduate programs abroad, to cultivate individuals who would contribute to brain bridging.

According to the interviews conducted by Chaikhana Media (2021), students see brain bridging in the following way:

[One interviewee] . . . notes that in recent years, technoparks, industrial parks are opening and new infrastructure related to green energy and alternative energy is being built. ‘And professionals are needed to work in this infrastructure. Therefore, I think that in the next 3–5 years, when those students return to Azerbaijan, they will be able to work both in the private sector and in the public sector.’

I remember there was an interview with the president. He said ‘we don't mind if our graduates stay abroad because they are also representing the country abroad.’ There aren't too many Azerbaijanis abroad, so it is a good representation.

Apart from that, universities sign more and more contracts with other universities abroad to expand exchange opportunities for students. The possible bonds between the educational and young career actors are said to act as a brain bridging between the countries.

Conclusion

The paper looked into the correlation between EMI and student academic mobility sponsored by the state programs, the latter being a catalyst to a brain drain in Azerbaijan. Based on the current literature, the study has revealed that there is, in fact, a strong correlation between EMI and study-abroad opportunities. We also revealed that brain drain strongly depends on the country's well-being. As an example, we witnessed the year 2016 when the results of the devaluation of the national currency accelerated the mass outflow of young specialists, and mainly students. However, some recent circumstances, including the COVID–19 pandemic, as well as the country's effective domestic policies, have demonstrated that in today's globalized world of technology, favorable economic conditions of the country may turn a brain drain into brain bridging. As to English, it remains the key international language of communication, a wide expansion of which proofs ELT insufficient and gives rise to EMI as a main catalyst to brain bridging.

DR. TAMILLA MAMMADOVA is an Assistant Professor in Humanities and Social Science at ADA University, Azerbaijan. She holds a PhD from the University of Santiago de Compostela, Spain, where she is a member of the SPERTUS research group. Dr. Mammadova has gained broad international experience. After completing her MA at the Azerbaijan University of Languages, she headed to France to complete pre-doctoral studies. Later, she moved to Spain to do another MA course and pursue a PhD degree. In 2019, Dr. Mammadova completed her post-doctoral research at the University of Fribourg, Switzerland. She is the author of numerous academic books and papers. Email: [email protected]

DR. TAMILLA MAMMADOVA is an Assistant Professor in Humanities and Social Science at ADA University, Azerbaijan. She holds a PhD from the University of Santiago de Compostela, Spain, where she is a member of the SPERTUS research group. Dr. Mammadova has gained broad international experience. After completing her MA at the Azerbaijan University of Languages, she headed to France to complete pre-doctoral studies. Later, she moved to Spain to do another MA course and pursue a PhD degree. In 2019, Dr. Mammadova completed her post-doctoral research at the University of Fribourg, Switzerland. She is the author of numerous academic books and papers. Email: [email protected]