As part of its drive to improve quality within the National Health Service (NHS), the government has published several key documents aimed at promoting reform (Department of Health, 1997). Clinical governance and clinical audit are key elements in this reform (Reference Scally and DonaldsonScally & Donaldson, 1998). The NHS Plan (Department of Health, 2000) set out a 10-year programme of service improvement. One of the areas given priority was waiting times. This is a key performance indicator monitored by the Healthcare Commission. The NHS Plan gives a commitment to reduce the maximum waiting time for outpatient appointments to 3 months by the end of 2005. To achieve this target, and other commitments, the government established the NHS Modernisation Agency in April 2001.

In the light of these performance indicators it was decided to audit waiting times at the Specialist Psychotherapy Service at Southfield House. Waiting times within the service had not been audited prior to the present study. However, there was a perception among clinicians that waiting times were lengthening. It was decided to benchmark the service against the standard that no patient should wait longer than 13 weeks for a first appointment. The interval between the receipt of a referral and its discussion at a referral meeting was also audited.

A search of Medline, Embase, Cinahl, Psychinfo and the King's Fund failed to find any audit of waiting times in a specialist psychotherapy setting. However, studies have addressed the more general problem of the relative lack of availability of psychological therapies. Given limited resources, it has been suggested that clients could be triaged using a rating scale to determine priority (Reference Walton and GrenyerWalton & Grenyer, 2002). Elsewhere, waiting times have been reduced by the introduction of training programmes in brief psychotherapies and group psychotherapy (Reference KellerKeller, 1997). However, it is argued that more fundamental organisational change is required, with the development of multidisciplinary departments capable of providing the breadth of psychological services (Reference PaxtonPaxton, 2004).

Southfield House is a multidisciplinary service offering a range of therapies including cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), psychoanalytical, psychodynamic, humanistic, interpersonal and group therapies. At the time of the initial audit, core psychotherapy staff comprised three consultant psychiatrists and seven other specialists with backgrounds in nursing, social work and occupational therapy (in Leeds a separate department of psychology provides sector-based psychology services). In addition, there were four specialist registrars and two senior house officer training places.

Although Southfield House is a tertiary service it accepts referrals from diverse sources, including: secondary mental health services, the psychology department, primary care and non-statutory organisations. At the time of the audit there was no standard format for referrals and no requirement for referring agencies to use a pro forma.

Referrals are processed by clerical staff, then forwarded to the referrals manager who groups them and presents them at a weekly referrals meeting. The principle function of the meeting is the allocation of referrals to therapists. This has usually been preceded by detailed discussion of each referral. A decision is made whether or not to invite the client for assessment and, if so, which modality of therapy is most likely to be appropriate. Accordingly, the referral is allocated to a specialist in that field. When a referral is not accepted for assessment the referrer is told why, and, where appropriate, directed to more suitable agencies. The referrals meeting has also been a forum for therapists to report the results of assessments.

Sometimes, further information is requested from the referrer. This information is usually of two types. First, if it is known that a person is already receiving psychological therapy, clarification is sought as to the modality of the therapy, its likely end date and the person's response to the therapy. Second, if a patient with complex problems is known to be receiving care from other mental health professionals, the referrer is asked for copies of relevant correspondence.

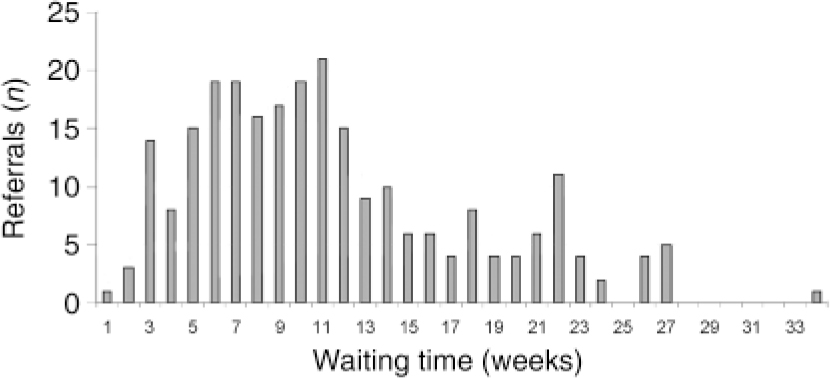

Fig. 1. Before re-audit: waiting time for first appointment in 2002 (n=251).

Method

The initial audit included all referrals to Southfield House in the year 2002. The number of referrals and the number and proportion of clients given appointments for assessment were calculated. Waiting times (defined by time from receipt of referral to date of first appointment offered) and times to discussion in the allocation meeting were also calculated.

Results

The initial audit showed that 355 patients were referred in the year 2002. Of these, 251 (71%) were given an appointment for an assessment.

The distribution of waiting times is shown in Fig. 1. The mean waiting time was 11.5 weeks, with 75 (30%) patients waiting longer than 13 weeks. The bimodal distribution of waiting times (Fig. 1) was striking and prompted an analysis of those people with longer waiting times. It was evident that in some instances appointments were delayed by requests from Southfield House to the referrer for more information. Moreover, this onerous role was being shared by only one or two therapists, compounding delays.

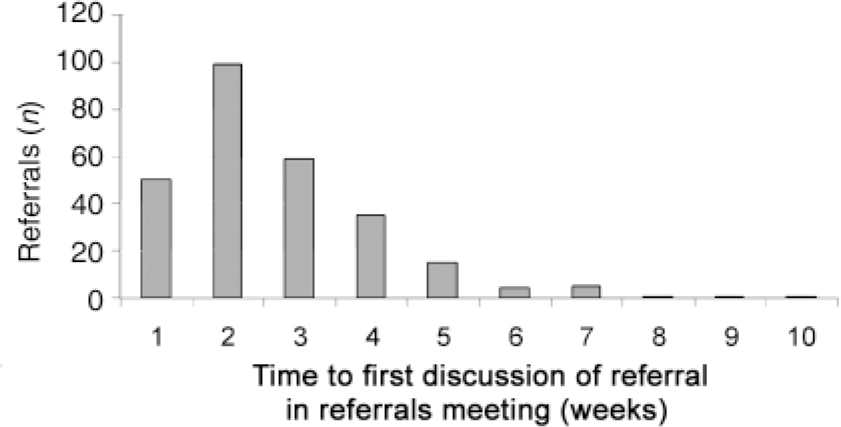

Data on the time to first discussion of referrals in referrals meetings were available for only 270 of the 355 referrals. The distribution of times between receipt of referral and first discussion is shown in Fig. 2. The mean number of weeks to first discussion was 2.7 weeks.

Reasons for delays included: postponement (e.g. until further information was available or until a particular team member was present); cancellation of meetings (e.g. during holiday periods); and in several instances, therapists failing to forward to the service-wide referral meeting referrals that had been addressed to them personally.

In 20 cases, information was deemed inadequate, prompting further liaison with the referrer. Of these, 11 (55%) were subsequently offered an appointment for assessment. The additional information sought included clarification about the nature of the problem, previous psychological interventions, the client's attitude to the referral and potential contraindications to therapy.

Fig. 2. Before re-audit: number of weeks between receipt of referral and first discussion at a referral meeting in 2002 (n=270).

Action plan

The results of the audit were reported within the service clinical audit meeting. A multidisciplinary and multimodal group of therapists, together with the service administrator, agreed to form a working party to develop an action plan to address the shortcomings identified in the audit. The action plan was as follows.

-

• Referrals meetings would be held weekly throughout the year (including holiday periods). To facilitate this, responsibility for managing the referrals process would be shared between three therapists. In addition, therapists’attendance at referral meetings would be monitored.

-

• Referrals meetings would give priority to the allocation of referrals. Allocation would not be delayed by the absence of a representative from a given modality or by excessive time devoted to discussion. The standard would be that patients are allocated to a therapist within 1 week of receipt of referral. Referral-to-discussion times would be recorded and monitored.

-

• The need for correspondence with referrers to seek additional information would be reviewed on a case-by-case basis. Ways of improving the quality of information provided by referrers would be explored.

-

• On receipt of each referral, the date of the 13 week deadline would be calculated and highlighted in the database.

-

• To aid clarity about therapist capacity, the service manager would maintain an up-to-date record of therapists’case-loads.

-

• More flexible ways of working (such as uncoupling the assessment and treatment phases of therapy) would be promoted. To this end, each therapist would designate specific times for conducting assessments.

-

• In keeping with national and local policy, a partial booking system would be introduced.

The recommendations and action plan were introduced in clinical governance meetings held at Southfield House in autumn 2003.

Results of re-audit

The re-audit considered referrals received in the first 9 months of 2004. Throughout this period a partial booking system was in operation. Of 200 referrals received, 144 people (72%) were invited to contact the department to book an appointment for assessment; 133 responded and were duly given an appointment.

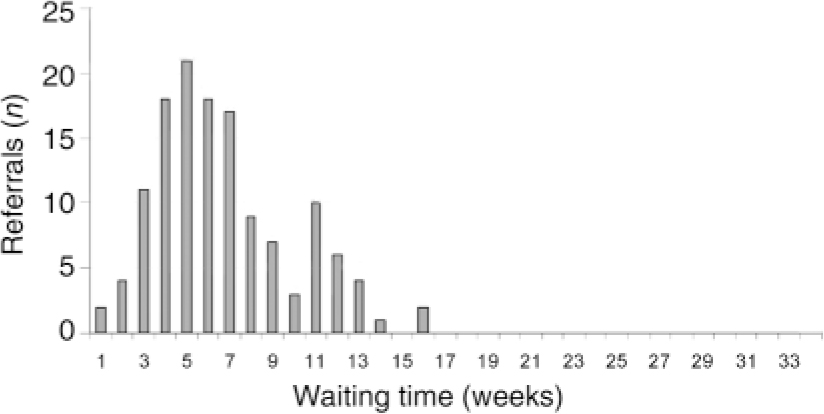

Fig. 3. Re-audit: waiting time for first appointment in 2004 (n=133).

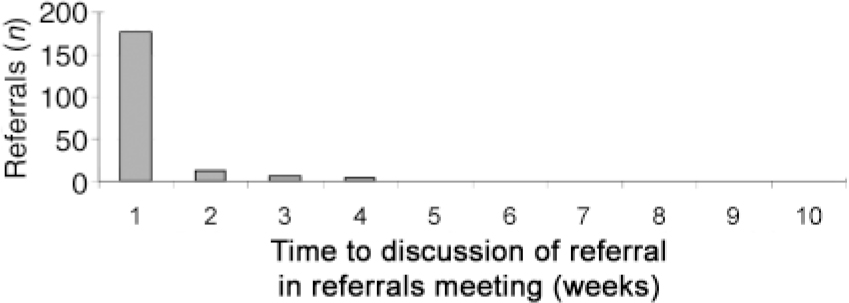

The distribution of waiting times is shown in Fig. 3. The mean waiting time was 6.7 weeks, with 3 (2.3%) people waiting longer than 13 weeks. The time between receipt of referral and first discussion in a referrals meeting is shown in Fig. 4. The mean number of weeks to first discussion was 1.2.

Statistics

Differences in the mean waiting times between the first audit (T1) and the second audit (T2) were examined for statistical significance using an independent samples t-test with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 12.0). The mean difference in waiting time between T1 and T2 (4.81 weeks) was statistically significant (T1: n=251, mean=11.46 weeks, s.d.=6.38; T2: n=133, mean=6.71 weeks, s.d.=3.17; t=9.7, d.f.=382, P<0.001). The difference remained statistically significant when the one extreme value of 34 weeks was excluded from the T1 data-set, giving a mean difference between the two audit times of 4.66 weeks.

Discussion

This audit examined waiting times to first assessment for referrals in an NHS specialist psychotherapy service. The initial audit showed considerable variation in waiting times with an unacceptable proportion of patients waiting in excess of 13 weeks. Factors contributing to delays included problems in the processing of referrals and in the monitoring of referral data. Having identified weaknesses, an action plan, owned and accepted by the service clinical governance forum, was developed. Re-audit has shown a substantial and statistically significant reduction in waiting times.

Fig. 4. Re-audit: number of weeks between receipt of referral and first discussion in a referral meeting in 2004 (n=200).

These improvements have occurred not only as a response to external pressures but from an internal desire for change. The audit has highlighted the importance of high quality clinical information and the preparedness of health professionals to embrace cultural change, both key elements of clinical governance (Reference Halligan and DonaldsonHalligan & Donaldson, 2001). It has also demonstrated that a sense of ‘ ownership’ of the audit process enhances the likelihood of a positive outcome.

Declaration of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution made by the clinical and clerical staff at Southfield House.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.