Introduction

As has been discussed in the previous chapters, a great number of languages in the world have experienced a significant displacement in their national and regional contexts, particularly in the last two centuries. Displacement comes from a process that forces certain languages into a ‘minority’ status – which rather than being a mere reflection of their demographic stature or grammatical integrity is the result of political and economic marginalisation. For these reasons, minoritised or minorised languages in the world are associated with marginal populations and spaces. Speakers are also discouraged by the lack of education in minoritised languages, as well as the lack of recognition of their art forms, like literature, music, or performance, among others. This, in turn, dissuades people from using these languages in new intellectual or artistic productions.

Language activists in different parts of the world are confronting this situation by reclaiming forsaken linguistic art forms, like traditional storytelling, song and oratory performances, among others. They are also experimenting with new forms of literature, performance and poetry, song composition and music, and other cultural activities like radio production, TV series dubbing, news and social media publications, multimedia installations and advertising. These art forms are used as strategic ways to revitalise their minoritised languages. In this chapter, we will introduce a handful of examples from the Americas, Oceania and parts of Europe, which could provide some general principles and guidelines.

When discussing arts in minoritised languages, we must keep in mind that while most art forms are meant to be enjoyed without linguistic interference – think of dance, painting, sculpture, architecture, photography and graphic design – virtually all artistic endeavours rely, to a certain degree, on language to be made sense of. In what follows, we will focus on arts that rely more significantly on words, speech or discourse, for example, literature (written and oral) and song. We will also look at mixed arts which combine image and speech in creative ways. I will divide the chapter into literary arts, musical arts and mixed arts (cinema, video and TV) to examine the potential of these social and cultural strategies to resist and prevent language displacement.

Literature in Minoritised Languages

Literacy in minoritised or endangered languages is significantly low at present, due to historical marginalisation, political hostility, and a lack of trained educators and teaching resources. In some cases, this is the after-effect of the destruction and prohibition of previous traditions and forms of writing. One clear example of this was the systematic eradication of Mexica and Mixtec pictographic codices and Maya hieroglyphic books during the colonisation of Mexico and Guatemala. Many other minoritised languages do not have an agreed writing system (see Chapter 14). Consequently, reclaiming minoritised literatures and developing new literary traditions are necessarily tied to questions of literacy, standardisation, normalisation and publishing.

For writers and publishers of minoritised languages, the main challenge is to create a readership, particularly in contexts where speakers are not even literate in the dominant language. Global concerns about the loss of linguistic diversity have moved a few national governments (especially in parts of Western Europe and Latin America) to provide funds and infrastructure in order to address these disadvantages. However, money and publications are not the only resources that an endangered language needs.

Language activists are trying to redress the interruption of local, unwritten literary traditions by compiling examples of spoken art, like storytelling, recitation, ritual dialogue, chanting and other surviving oral traditions. A growing number of states now offer support to revitalisers. For example, the Mexican government has sponsored the publication of literature in Indigenous languages since the 1980s. These publications, although always in bilingual form (Spanish and Indigenous languages), represent an important shift in relation to the previous monolingual policies of the Mexican state. The Contemporary Indigenous Literature series initially consisted of cultural monographs, collections of folktales, songs and prayers, and community theatre scripts. Later series have included new narrative forms such as fiction stories and novels, poetry and playwriting. Although these series purportedly aim to revitalise Indigenous languages, several critics point out that these bilingual books end up being used more by literary scholars and linguists than by Indigenous speakers. Distribution is crucial since these books tend to circulate predominantly within government and higher education institutions and community libraries, but rarely in commercial bookshops. An even more pressing challenge is that Mexican Indigenous speakers are still rarely taught and even less encouraged to read in their own languages.

Mexico’s case shows that increasing publication of books in endangered languages is not enough; guaranteeing their circulation and access, and encouraging their consumption by speakers is also necessary. Promotion of literacy in minoritised languages is an enterprise that requires both institutional and grassroots support. Growing access to the Internet in minoritised language contexts might provide new opportunities to promote literacy, but this is yet to be determined.

Compilation of traditional oral literature has been deemed an important way to identify aesthetic principles which could support the development of new literary styles. A good example of this is the investigative and creative work of Ana Patricia Martínez Huchim in Yucatan, Mexico. She was one of the first Maya women to research Maya oral literature, working first with children and later with adults. In spite of not being a fluent speaker, Huchim became a prolific writer, drawing inspiration from community stories and turning them into new tales that followed the Maya storytelling canon. Her collections of stories feature acute social commentary, shedding light on forgotten historical events, as well as denouncing gender injustice in community life, in true literary form.

Play-writing and theatrical performance also offer significant opportunities to dynamise minoritised languages. This literary and performative hybrid art form integrates different skills and taps from different sources which makes it an even more effective way to reinsert endangered languages in the public sphere. Among its sources we could have story compilations, historical re-enactment, or creative writing. Preparation of theatrical performances involves speech training, rhythm awareness, dialogue practice, memorisation, recitation, and improvisation. Plays are social events that prompt conversation, analysis and, on occasion, even debate, all of which could invigorate threatened and minoritised languages. These secondary, meta-performative events are key to infusing endangered languages with new life. Because these art forms require group work and cooperation, they could also strengthen collective identity and help to associate the language with play and socialisation. This is not only the case with theatre but could also potentially be a part of dance.

This is how the Kaqchikel-speaking members of the Sotz’il Art Group in the Guatemalan highlands understand their artistic and political work, which mixes theatre and dance to recount mythic stories in a contemporary fashion. The Sotz’il Group has developed an investigative and experimental practice that reclaims ancient Maya literary and performance aesthetics. The group formed in 2002 on the initiative of Lisandro Guarcax and a group of Kaqchikel-speaking high-school students. Their work echoed traditional community performances. Indeed, traditional performers from the community supported them with learning about customs, instruments, props and cultural knowledge. Confronted by stereotypical and offensive portrayals of their ancient art and historical heroes in schools and other public institutions, Sotz’il members have sought inspiration from representations of Maya musicians and dancers found in ancient books and paintings. They have used these images as a template to create new performances, copying postures, improvising movements, reinventing costumes, and writing dialogues for plays that deal with both the historical and the political challenges of today. Without strictly relying on text, Sotz’il’s recreations of theatre and dance creatively assemble myth, memory, and movement to reconnect young people with Kaqchikel culture and language. A more conventional literary outlet for Sotz’il’s experimentation has been the publication of artistic theory in their bilingual (Spanish–Kaqchikel) anthology Ka’i’ oxi’ tzij pa ruwi’ rupatän Samaj Ri Ajch’owen [Some words about the work of the Maya Artist], 2014.

A broad definition of literature in the context of minoritised languages should not only include playwriting, but also other forms of spoken art like singing and praying. The Royal Academy of the Spanish Language, for example, defines literature as ‘the art of verbal expression’ (my emphasis). Following this, ‘literature’ would have to include public storytelling (including ‘call’ and ‘response’), civic rhetoric, ceremonial discourse, ritual song, religious or historical dances, carnival speech or jokes, political chants or slogans, everyday sayings and proverbs, all of which encapsulate specific aesthetic principles. One form of performative literature that has become a favoured strategy for language activists will be the focus of our next section.

Minoritised Sounds in Emerging New Languages

The strong connection between music and language is not a new discovery. It was during the twentieth century, however, that language activists started to use song composition and performance in a more conscious and political way. One example of this was the Nova Cançó (New Catalan Song) movement during the late 1950s under Francisco Franco’s dictatorship in Spain. The Francoist regime had banned the use of regional Iberian languages, like Basque, Galician and Catalan, in public official spaces. Although singing in these languages was not strictly prohibited, song writers and singers, especially in the Catalan-speaking region, used this art form to highlight the imposed Castilian monolingualism in the music domain. Nova Cançó performers began translating and imitating French singer-songwriters (rather than employing traditional genres like havaneres or rumbas) but later developed their own distinctive style.

Translating popular hits is a strategy that continues to be followed by language activists. In 2015, Peruvian teenager Renata Flores Rivera became a social media sensation after posting a music video with a rendition of Michael Jackson’s ‘The Way You Make Me Feel’ in the Quechua language, which has gathered more than 1.7 million views to date. Copyright disputes seem to have been prevented by acknowledging clearly the original source of inspiration and avoiding associations with commercial interests.

Language revitalisers have also ‘invented’ new singing traditions and given birth to mixed performance genres (song and dance), as the Māori action song, waiata-ā-ringa, exemplifies. This waiata (song) genre is an innovation from the early twentieth century and was associated with the activism of the Young Māori Party. Āpirana Ngata, a prominent party activist, devoted himself to compiling and publishing traditional songs and oratory examples during this period. Waiata-ā-ringa combines Western melodies with the performing of culturally prescribed movements which convey Māori narratives. The combination of dance and singing, and the collective, playful and aesthetic nature of these performances have proven to be a popular strategy to promote and celebrate the Māori language, Te Reo, in Aotearoa/New Zealand.

Singing in one’s own language may be a mundane activity for many, but it can easily become an act of resistance, especially when its social dynamics change. The Yucatec Maya language, maaya t’aan, was widely used as the de facto lingua franca during the early twentieth century. Yucatec Maya people have preserved different forms of literature, written in Latin characters since the sixteenth century. Yucatecan trova, a local romantic song style which emerged in the early twentieth century, was initially a bilingual genre, but as the Indigenous language of Yucatan was gradually displaced by Spanish, Maya song composition became infrequent. In the early twenty-first century, however, young Maya speakers have started using global music genres like hip hop, reggae and rock to sing in their own language. The number of Indigenous-language hip hop singers in Mexico and other Latin American countries has grown significantly in the last two decades.

Music and song can converge in unexpected ways to help gain new audiences for displaced or minoritised languages. Sometimes this happens through the dynamisation of aged traditions in new genres and with new music technology, where old verses are remastered and re-recorded by young artists and put back into circulation. A good example of this is the work of the Comcaac or Seri rock band Hamac Caziim (Sacred Fire) who, in the 1990s, sought and obtained authorisation from their tribal government in northern Mexico to recreate festive and ceremonial chants in heavy metal form. A true literary tradition, Seri songs have contributed to maintaining a sense of community for this relatively isolated people in the Mexican Sonora state. Traditional songs follow harmonies based on a pentatonic scale, employ an arcane language style and explore landscape inspired themes. Hamac Caziim’s experiment, which has become known as Seri Metal, was well received by Comcaac elders and, more importantly, by young people. Their work spearheaded the organisation of festivals and other public events to make the language more visible, a sort of Seri renaissance in the early twenty-first century.

Lyrical performance may not be a common practice in all language contexts. For example, few Tzutuhil, Kaqchikel or K’iche ‘proper’ songs are known around the Atitlan Lake of Guatemala. However, the poetic intonation and metaphoric figures maintained by aj q’ijab’ (daykeepers, or religious specialists), which reflect literary traditions that go back to Maya Classic inscriptions, are a source of inspiration for some young musicians in the region. Combining this poetic heritage with his fondness for hip hop, René Dionisio, aka ‘MC Tz’utu’, has emerged in the popular music scene as an effective revitaliser of Guatemalan Maya languages. MC Tz’utu’s compositions reclaim and make productive use of decidedly Indigenous aesthetic resources like alliteration (repetition), and the use of semantic pairings also known as ‘parallelisms’ (for example ‘our language, our clothes’, a pairing that evokes ‘cultural tradition’). Although repetition of catch phrases from Western hip hop seems to mirror the parallelism of Maya poetic forms, the lesser importance of rhyming in MC Tz’utu’s rapping provides his work with a distinct Indigenous aesthetic.

As we have seen in this section, song and literary traditions are employed in innovative ways by language and cultural promoters. An aspect which is definitely present but relatively downplayed in relation to revitalisation strategies is the way in which language is embodied and becomes present, not just in everyday life but, perhaps more significantly, in larger public spaces. I will touch briefly on this dimension in our next segment.

Embodying Language: Cinema, Video and TV

Audio-visual media has become the predominant form through which cultural and linguistic contents circulate nowadays. This is also true of music, especially since the 1990s, which saw the beginnings of the music video as the preferred self-marketing medium in North America and Western Europe. Collaboration between musicians and filmmakers has sometimes resulted in true masterpieces, with awards being offered annually worldwide to different aspects of music film production.

As with Hollywood musicals, the relation between song and cinema has also been strong in other, non-Western, contexts like the powerful film industry in South East Asia. Songs and movies always went hand in hand in this densely populated, multilingual part of the world. Today, hundreds of films are produced every year in Hindi (Bollywood), Tamil (Kollywood), Telugu (Tollywood), Kannada (Sandalwood), Bengali, Malayalam (Mollywood), Marathi and Bhojpuri. These represent only a handful of the 122 major, and more than 1,500 minor languages spoken in India. To deal with this hyper-diverse linguistic landscape, Indian cinema experimented in the 1930s with the production of trilingual or multilingual films. The approach consisted of shooting the same scene in three or more languages, to create different versions of the same story. With the development of film technology, dubbing became the preferred solution to deal with linguistic diversity in cinema, not just in India but in Western Europe, too. Here, the protection of national cultural industries instituted the dubbing of English-language films and TV programmes in the official language, a practice that has been maintained in France, Spain, Portugal, Italy and Germany, to name a few. This is also common in Latin America, both in Spanish and Portuguese. Dubbing in minority or Indigenous languages has, however, been historically less common. We will examine two significant examples of this later in the chapter.

With greater availability and affordability of video recording equipment, the production of film and television in endangered languages is today seen as a good way of capitalising on the ubiquity and popularity of this medium. The number of video productions in minoritised languages is, however, still insignificant in comparison with the number of movies and programs released in English, Hindi, Mandarin, Taiwanese, Arabic, Japanese, Spanish, Portuguese and Yoruba. While the quantity of films in minoritised languages might not be significant, occasionally their cultural and political impact can prove more decisive.

This is the case of the film Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner, released in 2002 and directed by Inuit filmmaker Zacharias Kunuk. This movie is one of many videos released by Igloolik Isuma Productions, a loose association and production company which began making films in the 1990s in the Nunavut territory of Canada. Early productions by Isuma (‘To Think’) attempted to capture the daily lives and struggles of Inuit people, and often employed a voice-over narration in Inuktitut language. Atanarjuat was Isuma’s first full-length feature and the first ever fiction film in Inuktitut. The story was based on the legend of the fast runner, the title character, and takes place in a time before contact with White settlers. Paul Apak Angilirq was the one who thought about compiling the different versions of the traditional story and turning it into an approximately three-hour long movie. The relevance of Atarnajuat is clear to see: it was voted the best Canadian movie of all time by a poll of experts at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2015. The critical recognition and commercial success of this work has inspired other First Nations directors to create more material in their own languages. The production company has also created an online platform called Isuma.tv that aims to ‘honour oral languages’ and that currently hosts video content in more than eighty Indigenous languages.

A similar experience in South America, although without the same critical reception by the international film circuits, is the project ‘Video in the Villages’ (VIV). It was founded by a non-indigenous Brazilian, Vincent Carelli, in 1986, a time of political effervescence and instability in the region. Since then the project has provided financial and technical support to several Amazonian Indigenous people to create their own media in their own languages. VIV productions cover various political, spiritual and territorial aspects of the lives of approximately forty Indigenous peoples. Patricia Ferreira (Mbya-Guarani), Ariel Duarte Ortega (Mbya-Guarani) and Divino Tserewahú (Xavante) are some of the most prolific and talented Indigenous filmmakers to have emerged from this collaborative project. VIV productions travel from village to village by boat, retelling mythical and historical events, inviting the reinterpretation of Indigenous identities and galvanising the political energy of different peoples to defend their territories and ways of life.

As with Indigenous literature, one of the most important challenges of Isuma and VIV is the distribution of film materials. Although the Internet has facilitated access to their video production, consumption remains limited to movie connoisseurs, cultural activists and academics. Social media platforms like Facebook, YouTube and Vimeo offer the possibility of increasing their audiences. However, a lot still needs to happen for Indigenous films to have the power to make young people interested in learning real, endangered languages instead of made-up ones from global franchises, like Klingon (Star Trek), Elvish (Lord of the Rings) or Dothraki (Game of Thrones).

Before this can happen, perhaps the second-best thing may be what Diné or Navajo language activists decided to do in New Mexico. In 2013, the Navajo Nation Museum and Lucasfilm Ltd teamed up to dub Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope in the Diné language. The project was thirteen years in the making, the brainchild of Manuelito Wheeler, director of the Navajo museum. Searching for ways to preserve Diné, he first asked his wife Jennifer to help him translate ten pages of the movie script. He decided to use this film given its popularity among members of his reservation and because it is still considered one of the best films of all times. In addition to raising enough funds to pay for translators, dubbing actors in Diné and recording studios, time was one of the main challenges. The Diné dubbed version of the Episode IV was released on DVD as a limited edition the same year and can now be ordered online. The second full feature to be dubbed in Diné was the animated children’s film Finding Nemo, which was also made available as a DVD in 2016.

In 2013, two young Paraguayans, Pablo Javier and Víctor Fabián Báez, from Santa Rosa, Misiones, became a sensation on the Internet when they started posting homemade ‘parodies’ in the form of Guaraní dubbed video clips of popular TV programs, like the Mexican comedy program El Chavo del 8, and Japanese animated series ‘Pokemon’ and ‘Dragon Ball Z’. They began their dubbing with the most basic technology: a microphone, and hacking software. What inspired them was not a preoccupation for the preservation of the language (Guaraní is the most spoken Indigenous language in the Americas with an estimated eight million speakers, and the only Indigenous official language of the Mercosur trade region) but the thrill of hearing their mother language spoken in a global TV series. Despite the social media success they achieved, this did not result in a more professional and extensive project. They have nonetheless continued posting their ‘parodies’ on YouTube, hoping to monetise the thousands of clicks they get for their work.

The Art of Revitalising Languages

From the presentation of the previous cases (which are but a tiny sample of the myriad efforts that exist worldwide), some general principles and guidelines for working with arts, music and other cultural activities can be sketched.

Displacement and loss are strongly linked to the stigmatisation and lack of visibility of languages. To counteract these processes, language activists could:

(a) Reclaim forsaken written, performative and verbal art forms; a strategy that has the double effect of restoring forgotten or censured aesthetic traditions while, at the same time, strengthening the sense of worth in cultural and linguistic communities.

(b) Adapt traditional genres (chants, storytelling or dance), renew their artistic repertoire and/or create hybrid aesthetic forms for younger or new audiences.

(c) Use current technologies and social media to reach new audiences, inspire the younger generation, and increase the presence of their linguistic and cultural identities in the national and global scenes.

(d) Take advantage of the success, influence and familiarity that certain artistic products enjoy, like songs, films or TV series, and use these as templates and inspiration for linguistic and cultural reinterpretation. Although reinventing their own narratives and experiences through new media is a good base for revitalisation, not everything has to be created from scratch.

There are significant challenges to implementing these strategies. Some of the more apparent obstacles are presented here:

Audience creation: the low numbers of literate people in minoritised languages usually means that written publications and textual media only circulate in reduced social spaces. Language activists sometimes combine oral and written forms of communication, like radio programs and online podcasts, where those who are literate read out new poetry and narrative to those who have not been taught. The creation of audiences for other forms of art, like song and cinema, is also important given the disproportionate competition of cultural products in dominant languages and the stigmatisation of minoritised languages art forms.

Audience reach (circulation): in addition to the need to create new audiences, circulation is another important obstacle to deal with. While literature, music and films in dominant languages have well established marketplaces, minoritised language productions struggle to have even a symbolic presence in mass media. Radio stations won’t program their music, commercial cinema theatres won’t list their movies, and big TV channels won’t broadcast their videos. Endangered language cultural productions, like their speakers, are kept in the margins, in small government-sponsored music or art film festivals, or in specialised circuits of enlightened cultural consumers. The challenge here is not just to put minoritised languages in global circulation platforms (anyone can have a YouTube channel) but to do so in a way that creates a cultural shift and new attitudes towards them. A few globally watched TV series, and even big Hollywood productions, have signalled a new appreciation for linguistic diversity, but perhaps only for their self-interest. This is exemplified by the inclusion of dialogues in Scottish Gaelic in the series Outlander, or by the full-length feature Apocalypto, entirely in Yucatec Maya (which presented, on the other hand, historical and cultural distortions that were the topic of a heated debate in Mexico and Guatemala). But, while it seems that Netflix does not have a problem offering worldwide Klingon subtitling for the new Star Trek series (Discovery), it seems unlikely that it will similarly offer subtitles in Nahuatl, Quechua or Guarani to its subscribers in the Americas anytime soon.

In spite of these limitations, the success stories reported here seem to have benefitted from a core set of principles. The following are some of the more easily identifiable: a strong commitment to the language and culture, long-term grassroots collaboration and engagement, reflexive and extensive research, social inventiveness, technological curiosity and creativity, cultural audacity and experimentation in close dialogue with the keepers of tradition (so as to prevent community divisions), and strategic alliances with a wide range of stakeholders, including governments and cultural industries, to highlight but a few.

We are still a long way from being able to solve the seemingly unstoppable loss of linguistic diversity in the world with a handful of steps and recipes. But, as some of these examples have shown, even the smallest of actions can contribute to the increase in the presence and dynamism of minoritised and endangered languages.

16.1 Art, Music and Cultural Activities in the Revitalisation of Wymysiöeryś

The revitalisation of Wymysiöeryś wouldn’t be so advanced today if we hadn’t taken up the task of revitalising not only the culture, but also the inhabitants of Wilamowice. We started this when we were only teenagers, together with Tymoteusz Król. Back in the 1990s, a person who encountered our town would only be presented with colourful costumes and old cottages – just the view that journalists would use when they wanted to show the last speakers of Wymysiöeryś. The regional ensembles of dance and singing presented only the costume and folklore.

I began my personal engagement with language revitalisation as an adventure with the regional ensemble as a young child. Back then I had no clue how complicated the problem of revitalising Wymysiöeryś culture was. Having joined the children’s ensemble ‘Cepelia-Fil’ I still didn’t feel engaged in Wilamowice itself. Nobody could explain to me the phonetically transcribed lyrics of songs (luckily, even back then I spoke with Tymoteusz and my great-grandmother in Wymysiöeryś). Nobody made that sure the costumes people wore reflected faithfully a specific local dress code – even though it is an important marker of identity.

Luckily, in 2007, Tymoteusz and I both joined the Song and Dance Ensemble ‘Wilamowice’. It might seem that the actions of such ensembles are folkloric in nature and destined only for the stage, i.e. that they form a mixture of ‘the nicest looking’, most pleasing elements of culture for the audience, yet are completely deprived of deeper reflection. Nothing could be further from the truth.

The ensemble was founded in 1948, only three years after the Wymysiöeryś language and culture had been banned by local officials collaborating with the communist authorities. For many years it functioned as a ‘time capsule’ as members collected costumes, their names and meanings, old songs and poems, and – above all – embraced the eldest inhabitants of the town who passed on their knowledge to the younger members and also their language, when they had the courage to do so. Thanks to the ensemble we could reach a greater number of inhabitants.

Through the ensemble we got engaged with the activities of the Association ‘Wilamowianie’, a NGO that has enabled us to start a more conscious revitalisation program. In the framework provided by the Association we have organised many cultural events which were strongly oriented towards promoting Wymysiöeryś in the community and changing linguistic attitudes, which still view Wymysiöeryś as ‘something negative’ (see Chapter 7). We tried to keep every meeting relaxed – some topics weren’t at all connected with revitalisation. However, we have always tried to ‘smuggle in’ Wymysiöeryś themes – like during a family fair which included a movie created by our youths about the ‘Pierzowiec’ (feather plucking) tradition. We attempted to make our activities more attractive by including excursions, meetings and workshops that could reach the biggest possible number of inhabitants.

Thanks to our collaboration with the Faculty of ‘Artes Liberales’ of the University of Warsaw, we organised several international events which made the community members aware of the huge external interest in the revitalisation efforts taking place in Wilamowice. Showing the inhabitants how much their cultural heritage is appreciated in academia made it more important to them too. We have also understood the need to ‘de-folklorise’ our activities, while keeping respect for traditions. Thus, Wymysiöeryś also became a medium for modern culture. In 2014, a theatre group was formed, called ‘Ufa fisa’, literally ‘On the feet’ (referring to a metaphor of making Wymysiöeryś culture able to stand again on its own feet). The actions of this group allowed more people to engage in cultural revitalisation and to learn the language, including those people who simply wouldn’t like to or couldn’t attend regular classes. Moreover, the exclusive use of Wymysiöeryś on stage fosters the creation of new intergenerational bonds: to understand the plot, spectators have to ask the eldest speakers and the teenagers who have learned the language and this makes them feel empowered. Staging our performances both in the town and neighbouring villages as well as in the Polish Theatre in Warsaw (see Figures 16.1.1 and 16.1.2) is an additional way of raising the prestige of the language and the awareness of its value as an important asset, both locally and more widely.

Figure 16.1.1 Performance in Wymysiöeryś, Uf jer wełt, Polish Theatre in Warsaw.

Figure 16.1.2 Performance in Wymysiöeryś, Ymertihła, Polish Theatre in Warsaw.

The next step was the creation of a band comprised of the members of the Majerski (fum Biöetuł) family (see Figure 16.1.3). They perform covers of modern songs translated by us and our students, thus proving to the skeptics that Wymysiöeryś is not only suited to old local songs. The new songs are real earworms – even those who don’t learn Wymysiöeryś sing them. We also make sure that Wymysiöeryś is always present in the local landscape – not only on various information boards but also during events that are not directly related to revitalisation itself, such as during street fairs and festivals where we promote Wymysiöeryś using merchandise such as t-shirts, bags, badges, mugs and banners.

Figure 16.1.3 Concert in Wymysiöeryś, the Majerski family.

Luckily, the last few years have proved that the effort put into the revitalisation of language, culture and community members has been fruitful. Language attitudes have changed. Many activities initiated by us now have a life of their own – the inhabitants introduce Wymysiöeryś into their environment and the youth organise their own initiatives, like the first Wymysiöeryś Day or location-based games in Wymysiöeryś. This makes us enormously happy.

16.2 Fest-noz and Revitalisation of the Breton Language

The Breton language, one of languages of Brittany, France, is an endangered language with about 200,000 speakers, mainly from the oldest generation. There are also a few dozens of thousands of new speakers. One of the most significant Breton cultural activities is a fest-noz (plural festoù-noz), the ‘night festival’ during which people get together, dance (not only) traditional Breton dances, enjoy themselves, and create a unique community connected by participation in Breton culture and – in some cases – by the use of Breton language. Nowadays these events are held throughout Brittany at all times of the year, in every possible location, with participants of all generations. They reaffirm that Breton culture is still alive. The music at a fest-noz is usually performed live, in most cases in Breton, although the range of possible accompaniments is broad. The most typical is the kan an discan (‘call and response’) song style, which involves singing without instrumental accompaniment by two or three individuals, whose voices overlap distinctively. The bagpipe-bombard, a traditional woodwind instrument pairing, also appears, playing a similar type of music. Yet very often there are whole bands on stage with ‘modern’ instruments.

The type of music, the place of performance and the participants differ according to when and by whom the fest-noz is organised. The functions of fest-noz have changed, just like the function of the Breton language. When daily life in the Breton language was concentrated in the rural areas in Lower and Central Brittany, traditional dances and festivities were related to the agricultural year: fest-noz developed from celebrations after collective community work was completed. These customs could not have survived the changes that took place in Brittany during the 1920s and 1930s: the appearance of new technologies moved the Bretons towards French culture and France’s conscious centralist policies targeted minority cultures and languages. These policies ridiculed and humiliated Bretons and their language. During the first half of the twentieth century, the Bretons abandoned their language and traditional dances.

The revival of the Breton language and fest-noz started in the 1970s. Speaking and singing in Breton came to be regarded as a moral duty of young people whose parents had rejected it. The struggle for a Breton way of life became part of the social movement of the 1970s. It was when young people began contesting official culture and expressing their revolt in a festive, musical way. The concept of fest-noz as a rural festival became widely accepted and it perfectly matched the social attitudes of young Breton activists who were searching for their roots. As a result, fest-noz provided a link between the worlds of the ‘young’ and the ‘old’, between ‘modernity’ and ‘authenticity’. Fest-noz events were no longer seen as pure entertainment or even a manifestation of pro-Breton attitudes; they became a way of life. The 1970s were successful in bringing forward the question of the Breton language as an important element of Breton culture, as well as re-evaluating Breton identity. Breton music, literature, theatre, and audiovisual arts bloomed. In 1977, the first Diwan community-run immersion school was formed. Since Diwan schools received no subsidies, money required to run them was collected during fest-noz organised by school collectives, activists and friends. After that period fest-noz lost some impetus. The late 1990s saw the arrival of a new style of fest-noz, closely linked to the Bretons’ fast-changing lifestyles and matching the progressing urbanisation as well as the advent of new, digital media. There are now Cyber Fest Noz events with several dozens of dancers live-streamed and transmitted through the Internet and accessible all around the world. The format is appealing to young people and makes participation in a minority culture attractive. Over time, fest-noz became an integral part of Breton culture. It did change style and function, but it has always been connected with Breton identity. It has also been a tool for Breton language revitalisation as many young people open themselves to the Breton language thanks to participation in these events. With its festival character, it is easily accessible to people; it allows those who want to use Breton to meet and develop closer relationships; it is also a place where most Breton activist movements and ideas come into life.

16.3 Modern Music Genres for Language Revitalisation

The arts, and musical production in particular, are becoming ever more central domains in grassroots efforts for language revitalisation in Latin America. Modern music genres such as rock, reggae, rap among others have been appropriated by Indigenous youths all over the continent. In Mexico, for instance, a growing number of bands are using Indigenous languages as a vehicle for artistic expression: Sak Tzevul (rock in Tzotzil), La Sexta Vocal (ska in Zoque) or El Rapero de Tlapa (rap in Mixtec) are examples of cultural activism among youths who look to expand their languages into new domains of use. Rappers from other Latin American countries, such as B’alam Ajpu in Guatemala, Luanko and the band Wechekeke ñi trawun in Chile, or Liberato Kani in Peru (to name but a few), are some outstanding examples of artists who have an already extensive career singing in Indigenous languages (Tzutujil, Mapudungun and Quechua, respectively). In the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico, hip hop as a cultural movement has become particularly prominent, and a sizeable number of Mayan rappers use now Yucatec Maya in their performances. If we consider the number of online views of songs such as Ki’imak in wóol by Tihorappers Crew (over 450,000 views in two years on YouTube) and the overwhelmingly positive comments to performances in Indigenous languages, the impact that these songs can have in changing negative attitudes towards Indigenous languages is noteworthy.

Some central aspects of rap make it a particularly productive genre for language revitalisation purposes. On the one hand, the central place that verbal fluency and creativity play in rapping aligns with Indigenous cultures that often favour oral ways of cultural expression, and, on the other, the local adaptation and recreation of hip hop as a global popular movement associated with modernity and ‘coolness’. As is well known, one of the ideological pillars of contempt for Indigenous languages is the alleged inability of these languages to express modernity and their unjustified association with cultural backwardness. Lastly, hip hop performances may incorporate a political element and provide a platform for the expression of marginalised voices. Some highly politicised Mapuche rappers, for instance, use hip hop as a platform for broader social struggles that include demands for language rights and political recognition.

Several video clips of Indigenous rappers are available on YouTube; try searching for the groups mentioned. Their music can also be found on other online platforms such as Soundcloud, Hulkshare and even Spotify.

16.4 The Jersey Song Project

Most people understand that songs can be a great way to help learn a language and perhaps remember some important phrases or patterns, but in fact the value of music for language revitalisation goes much deeper than that. Music is of course one of the most powerful ways to keep a language alive in our hearts and imaginations, and music can be profoundly connected to identity. Through music we can create inspiring and memorable collective experiences that can really help boost the status and public image of a language. When used in a culturally sensitive way, music can be a very versatile and useful tool in the linguistic toolbox.

One successful example of this from my own experience is The Jersey Song Project (which I have to say is an idea I stole from some friends in Guernsey!). The small British island of Jersey, in the Channel Islands, is home to the endangered language Jèrriais (a local version of Norman). As a local musician and activist I’ve been finding out how music can help in the revitalisation process. The central concept of The Jersey Song Project was to facilitate and curate collaborative songwriting between local musicians (who didn’t speak much Jèrriais, if any) and Jèrriais speakers, towards a final performance of songs that could be on any theme and in any genre, but would include at least one word of Jèrriais in the lyrics. Over the course of a few months in 2018, I advertised the project and organised for twelve local bands and solo artists to work with Jèrriais speakers and come up with something for the final gig. This took place at a professional performance venue as part of a local festival in the autumn.

The project was a real success, not just in terms of the final gig going well, but for the deeper connections that the musicians and audience made with the language, and also for the excellent publicity the whole project generated over those few months. I’d highly recommend running a similar project wherever there is enough of a local music scene for it to be appropriate (like I said – I stole the idea, so please do steal it from me).

Just a few practical pointers … I’d say there are three main ways of getting the collaborations going:

(1) The ideal way: musicians could meet up with native speakers and write something entirely new together (you’d need to organise this carefully to make it go as well as possible).

(2) Musicians could set an existing endangered language text (e.g. a poem) to music, with the support of native speakers or teachers.

(3) Musicians could work with native speakers/teachers to translate some of their own lyrics of a non-endangered language song they’ve already written.

Cover versions are OK, and the right song could be very popular, but you might run into copyright issues; and anyway, participants will probably engage more deeply if they use their own songs. Also, I’d say allow plenty of time for the process to unfold and try to make as much of a public ‘splash’ as you can with whatever you might do for the final performance, or recording, or both! Finally if you do run your own version of this, please get in touch as I’d love to hear all about it … Bouonne chance m’s anmîns! [Good luck my friends!]

16.5 One Song, Many Voices: Revitalising Ainu through Music

The Ainu are an Indigenous group native to the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido, the island of Sakhalin and the Kurils. Their language is critically endangered, although there are ongoing efforts to improve its profile, and increase the take-up of the language. Those of Ainu descent are also electing to become more visible, both within Japan, and as part of the global Indigenous community. One of the ways that some Ainu are demonstrating and transmitting their cultural and linguistic identity is through music.

Traditional Ainu music relies on singing, rekuhara (throat singing), mukkuri (mouth harp), and in the Sakhalin tradition, the tonkori (a plucked string instrument). Upopo (domestic work songs) tend to be simple in structure, with many songs sung in rounds. Yukar (sung epics) are formed of a short repetitive melody, and a sakehe (refrain) unique to each yukar. Contemporary Ainu music draws on many of these elements, but there is still diversity in how the music is expressed, although the use of the Ainu language, in titles or lyrics, remains the defining element.

Artists such as Oki Kano and ToyToy demonstrate the breadth of contemporary approaches to Ainu Music, but it is perhaps the group Marewrew who are most prominently weaving discussions about the language, and audience interaction with the language into their performances.

Marewrew is a group comprised of four female singers of Ainu heritage, who originally formed in 2002 to work with Oki Kano, the most well-known Ainu musician in Japan, and who later began performing as an independent ensemble. They perform upopo, some of which they have learned directly from family members, either acapella (unaccompanied singing) or accompanied by clapping or the mukkuri. All their material is performed in the Ainu language, and during performances they wear traditional clothing, and sometimes recreate the facial tattooing that Ainu women wore traditionally. Their music is based on simple foundations, repeated rhythmic and vocal patterns, and the use of nonsense syllables; but it is hypnotic and compelling. As a listener, understanding of the language is an additional benefit but not a crucial requirement for enjoyment. However, Marewrew enjoy enabling their listeners to interact more with the music, and actively encourage participation and understanding of the songs’ contexts.

Marewrew not only explain the meanings of songs, they also teach a number of songs during their sets, creating a shared space where the audience become active participants in a performance that uses the Ainu language. These ‘educational segments’ are almost delivered as mini-workshops, inviting further questions and queries from their audience. At a 2018 concert in east Tokyo that I attended (see Figure 16.5.1), this collaborative approach went even further, with a number of audience members not only knowing some of the songs performed, but offering translations of Ainu terms if one of the singers was unsure of the most accurate Japanese term. From singer to audience and back again, a teaching and expansion of vocabulary and context: everyone present engaged in learning and disseminating Ainu. Leaving a concert, or coming to the end of recording, may of course be the end of the process: we generally listen to enjoy music, not to learn. However, the potential is there for a listener to seek out more recordings, to want to understand, to actively experience more, and part of that experience can be learning more of the language. Hearing Ainu music for the first time as an undergraduate in the early 2000s certainly set me on that path, that just over fifteen years later, sees me researching the impact of Ainu language music on the language and actively learning Ainu myself.

Figure 16.5.1 Concert poster

Thus, a single song, Umeko Ando singing Saranpe as it happens, was enough to make me want to move from being a passive admirer of Ainu music and the Ainu language, to becoming an active participant: to learn and disseminate, not merely appreciate.

16.6 The Language Revitalization, Maintenance and Development Project

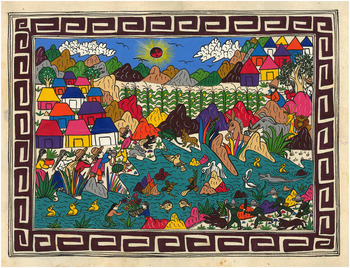

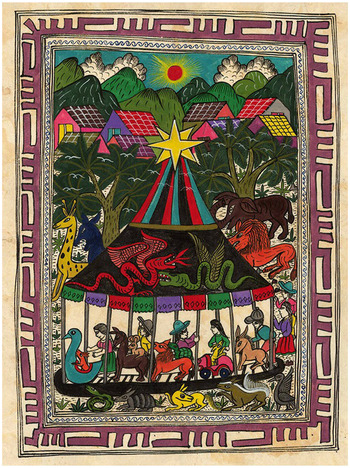

The Language Revitalization, Maintenance and Development Project (PRMDLC) in Mexico has been active for over three decades. Based on the idea of direct collaboration between speakers and researchers, the PRMDLC runs collaborative workshops to encourage a high level of participation. The PRMDLC starts from the recovery of peoples’ own language and culture, producing oral and image-based culturally appropriate materials, recreating them in prestigious media such as a TV screen, where Indigenous children rarely see their languages. Therefore the basic goal of the PRMDLC is to establish a (re)vitalising corpus; among others, a collection of printed, audio-visual and multimedia materials in Indigenous languages, produced and consumed by speakers themselves, while at the same time aiming to impact a broader audience (see Figures 16.6.1 and 16.6.2).

Figure 16.6.1 Los sueños del tlacuache.

Figure 16.6.2 ‘Carrusel’. Los sueños del tlacuache.

The PRMDLC holds revitalisation workshops aimed at encouraging and/or reinforcing permanent revitalisation through self-developed activities such as language games and music, from the bottom-up. Speakers are credited as the first and principal (multi)authors of multimedia products, including local tales as The Mermaid and the Opossum, riddles and tongue twisters, books, documentary films, games, and different musical genres (for example rap, rock, jarocho music). Participation of speakers is highly valued and incentivised, dignifying their languages and cultures. For instance, we have worked, among others, with a native artist and two Maya-speaking linguists and one anthropologist, leaders of the Maya team. They have seen their work published and available at major bookstores around the country and beyond, as well as included in multimedia products (Maya riddles, tongue twisters, tales) circulating on the Internet and even on public television. They are committed to disseminate the products within their own communities – their primary audience.

The PRMDLC workshops are organised as follows. Participants are summoned in events such as local patron saint festivities. These festivals are favourable occasions for bringing together many people, including migrants who have moved to big cities or even the USA, and visitors from several other local towns. Children attend workshops with their siblings, parents or grandparents, promoting links between generations. Children are invited to watch an animated movie: after showing the riddle(s) or the Mermaid/Opossum movie(s), the floor is thrown open to participation. Local champions leading the workshops invite the audience to repeat a tongue twister, or ask if someone knows another similar version of the stories, opening up the possibility of children’s spontaneous participation and even other emergent dynamics. Participants can express themselves freely. In principle there is no time limit (most sessions last from two to five hours). This allows for a relaxed atmosphere, unlike typical school dynamics. For example, animated riddles are shown, a genre that engages audience participation. This motivates strong participation by children, who suggest diverse, not conceived as ‘correct’ or ‘incorrect’ answers to the riddles (for instance the reply to the Nahuatl riddle Maaske mas tikwaalantok pero tikpiipiitsos (‘No matter how angry you are, you are going to kiss it anyhow’) can vary, ranging from a bottle to an aatekoomatl, ‘drinking water gourd’, or even other possible emergent answers. Riddles, tales, and tongue twisters are bastions of linguistic and cultural retention. Riddles, for example, are a powerful genre that calls on interaction and verbal play, not to mention tongue twisters that are culturally powerful language games stimulating interaction and cultural continuity.

In this way the PRMDLC develops a method of indirect revitalisation. This means that participation is open to spontaneous, not forced participation, in ‘natural’, cultural sensitive ways. It stimulates intergenerational transmission of the endangered language. In this sense, it is up to children whether or not to participate. It is very different from formalised ways of participation typical of school contexts that work as inhibitors of Indigenous knowledge and tongues, and therefore favour assimilation.