In many European cities, statues and sculptures form what might be called a “second population.” Originally, this held particularly true for cities with ancient heritage. Writing in the twilight of late antiquity, Cassiodorus spoke of Rome as a city with a “copious population of statues.”Footnote 1 In later centuries, the Renaissance and the Baroque led to a further growth of this “population.” In the eighteenth century, Goethe remarked that “in Rome, besides the Romans, there was also a people of statues.”Footnote 2

One type of statuary (re)appeared relatively late in Europe's lithic population: the caryatids. Only in the early nineteenth century did these female column-statues become a common sight in European architecture. From that point onward, however, they multiplied rapidly. By the fin de siècle, caryatids formed a veritable tribe among Europe's “population of statues.” Caryatids held up roofs, portals, and balconies—but, on a symbolic level, they also carried the full weight of the nineteenth century, that age of “epic burdens.”Footnote 3 This article explores, without any claim to completeness, the cultural history of caryatids in nineteenth and early-twentieth-century Europe. The focus will be on central Europe, and three cities—Berlin, Frankfurt am Main, and Vienna—play a particularly important role in this exploration. Through a reading of historical, visual, and literary sources, the article probes how these statues came to embody, on both a material and a metaphorical level, the social aspirations and societal rifts that marked the bourgeois age. The nexus, real and imagined, between caryatids and Jews is particularly illustrative here. As we will see, nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Jews who aspired to social recognition used caryatids to project a cultured habitus, to display social status, and, in some cases, to give expression to a particular kind of Jewish self-fashioning. At the same time—and in ways both related and unrelated—the growing discourse of racial antisemitism attacked these aesthetic choices as illegitimate cultural appropriation. What is more, it turned caryatids, associated as they were with servitude and submission, into a trope for claims about the supposed and irredeemable inferiority of the Jewish people as a race. In tracing these antagonistic and largely forgotten discourses, the article seeks to shed light on a larger subject that is still underexplored: the complex entanglement of architecture, religion, and race in the long nineteenth century.

The Nineteenth-Century Caryatid Renaissance

The late (re)appearance of caryatids in European architecture was largely due to the late reception of their ancient models. The best-known group of ancient caryatids stands at the southern porch of the Erechtheion, a temple from the second half of the fifth century BCE that forms part of the Athenian Acropolis. The original six marble caryatids—since replaced with replicas—bore the architrave of the so-called Porch of the Maidens. (See figure 1.)

Figure 1. The caryatids (modern replicas) at the southern porch of the Erechtheion, Athenian Acropolis. (Image: Harrieta171, CC-BY-SA-3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Throughout the medieval and early modern period, the Acropolis caryatids received little attention.Footnote 4 Only the onset of philhellenism and the gradual rise of mass tourism from the late eighteenth century onward turned the Erechtheion and its porch into an iconic attraction. Indeed, the first accurate visual depictions of the Erechtheion caryatids date to the late eighteenth century.Footnote 5 The politicization (and spoliation) of the Acropolis ruins further contributed to the new prominence of the female statues: in 1800, the British ambassador, Lord Elgin, arranged for the removal of one of the six caryatids and had it shipped to London, where it has been on display at the British Museum since 1816. For all these reasons, the Acropolis shaped the ninenteenth-century imagination of caryatids, even if these exemplars were not the oldest of their kind.Footnote 6

The genre of the female bearer-figure needs to be distinguished from its male counterpart: the atlas (also known in Latin as telamon). In Greek mythology, Atlas, a rebellious Titan, is condemned to carry the celestial spheres—a punishment imposed by Zeus himself. In later centuries, it became common to depict Atlas as the carrier of the celestial globe. In any case, architectural atlantes typically display the heavy weight of their burden: often the muscles of the upper body are visibly tense and the head is bent forward, with a grimace.Footnote 7 (See figure 2.) By contrast, caryatids seem to bear their load more lightly. Unlike atlantes, caryatids typically use their heads, not their hands, to carry the burden, nor do they show strain. Standing in an upright posture, their heads balance the entire weight; the hands remain in a relaxed position, or they hold sacrificial vessels.Footnote 8

Figure 2. André le Brun, Atlantes supporting the central balcony, 1787. Tyszkiewicz Palace, Warsaw, 1785–1792. (Image: Bartosz Morąg, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Still—and this is crucial for the contexts delineated in this article—caryatids are ultimately caught in the same state of subservience as their male counterparts. Indeed, since ancient times, caryatids have been construed as captives, irredeembably bound up with the stones they must carry.Footnote 9 In Hegel's apodictic words, caryatids “have this character of being pressed down, and their costume indicates the slavery which is burdened with the carrying of such burdens.”Footnote 10 This interpretation can be traced back to Vitruvius, the Roman author and architect whose canonical Ten Books on Architecture, composed in the first century BCE, have done more than any other ancient source to popularize this notion. In a section from the opening book, dealing with the education of architects, Vitruvius explains:

The Peloponnesian city of Caryae had sided with the enemy, Persia, against Greece. Subsequently, the Greeks, gloriously delivered from war by their victory, by common agreement declared war on the Caryates. And so, when they had captured the town, slaughtered the men, and laid a curse on the inhabitants, they led its noble matrons off into captivity. Nor would they allow these women to put away their stolae and matronly dress; this was done so that they should not simply be exhibited in a single triumphal procession, but should instead be weighted down forever by a burden of shame, forced to pay the price for such grave disloyalty on behalf of their whole city. To this end, the architects active at the time incorporated images of these women in public buildings as weight-bearing structures; thus, in addition, the notorious punishment of the Caryate women would be recalled to future generations.Footnote 11

Vitruvius's origin story is questionable, both on philological and archaeological grounds.Footnote 12 It seems far more plausible that the term caryatid originally reflected the custom of Caryae's women to stage exotic dances in honor of the goddess Artemis.Footnote 13 This would mean that, in ancient Greece, sculpted caryatids represented cultic dancers, not captives. This theory, however, was not advanced before the nineteenth century, and even when it was, the specialist arguments of philologists hardly unseated the deep-rooted view of caryatids as an exemplum servitutis, a sculptural embodiment of servitude.Footnote 14

The philological critique of the Vitruvian account certainly did not prevent or impede the nineteenth-century renaissance of caryatids. In fact, caryatids began to appear everywhere: in furniture, craftwork, and—more than anywhere else—in architecture. In the preceding centuries, architects and artists had pored over Vitruvius's text, but very few of them had had opportunities to study ancient caryatids in situ. This limited firsthand knowledge explains why caryatids remained a rare species in medieval and early modern architecture.Footnote 15 In fact, well into the eighteenth century, they were largely limited to aristocratic palaces.Footnote 16

But the social and economic rise of the bourgeoisie changed that. As the bourgeoisie's economic power grew in the nineteenth century, so did its self-confidence. This led, among other things, to an unprecedented architectural competition with the aristocracy.Footnote 17 The desire for status symbols and their prominent presentation played an important role in the caryatid fashion in bourgeois residences. Just as important, however, was the wish to display one's education—or Bildung, to use the almost mythical German term—and, more specifically, one's familiarity with the cultural heritage of antiquity. In this context, we observe a changing function of caryatids in architectural designs. Aristocratic palaces had employed the female figures as an exotic decorative element, often displayed in interior, gallery-like spaces. Prussia's “state architect” Karl Friedrich Schinkel explicitly declarded that caryatids should not be installed on the main facades of buildings.Footnote 18

Yet this is precisely what happened in nineteenth-century bourgeois architecture: caryatids, paragons of the sublimation of fatum into art, appeared everywhere on the facade, deliberately facing the outside world. They carried balconies, loggias, bay windows, and—most commonly—entrance portals. (See figure 3.) Whoever wished to enter the house had to pass by the caryatids. Walter Benjamin, who grew up in Grunewald (the most bourgeois of all fin-de-siècle Berlin neighborhoods), vividly described the powerful impression that this mythological facade population left on him. In the autobiographical memories of his “Berlin Childhood around 1900,” Benjamin describes the caryatids as a “race of threshold dwellers—those who guard the entrance to life, or to a house.”Footnote 19

Figure 3. Franz Melnitzky, Caryatids at the Haus Liebieg, Inner City, Vienna, 1859. Commissioned by the wealthy textile manufacturer Johann Liebieg and built by the architects Ferdinand Fellner, August von Sicardsburg, and Eduard van der Nüll, this building (1857–1859) is a fine example of the bourgeois taste for caryatids. (Image: Yair Haklai, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

“The wealthy Israelites / Build with Caryatids”: The Rise of a Prejudice

Not everyone, however, shared Benjamin's sympathethic sentiment for the caryatids. In an abstract vein, Hegel criticized it as “a misuse of the human form to compress it under such a load.”Footnote 20 On a more concrete level, the German art historian Alfred Woltmann voiced criticism in his widely read Architectural History of Berlin (1872). In the chapters dealing with contemporary architecture, Woltmann admitted that the ancient caryatid, as an enhanced substitute for the column, could be “a most effective means of heightened expression”—but only when it was “applied moderately.” In the bourgeois architecture of nineteenth-century Berlin, Woltmann saw an unjustifiable inflation of caryatids. They were ubiquitous—“at portals, under balconies, above columns, under columns”—and most of the time, the “slender maiden” carried structural weights that were disproportionately heavy. For Woltmann, this was not simply a technical problem, but also an aesthetic one: “The Hellenic maidens, which appear at the Pandroseion on the Athenian Acropolis to carry out a solemn cultic duty, have been degraded to serve the needs of private luxury and to carry out quotidian labor.”Footnote 21 In his view, this “caryatid luxury” (Karyatiden-Luxus) amounted to grotesque “facade gymnastics” (Façaden-Gymnastik). Woltmann viewed this phenomenon as symptomatic of what he considered a general tendency of the period: “an addiction to refinement that fails to go beyond the tawdry, a pursuit of glamor and wealth that can only achieve trifles—pleasant details and clever execution—but never attains the power of an overall effect.”Footnote 22

Five years after Woltmann, another historian of art and culture weighed in on the issue—Jacob Burckhardt, no less. In his letters from a journey through Germany (1875), the Swiss scholar recounted his impressions of the newly formed empire and its major cities. It is well known that Burckhardt had rather ambivalent feelings for his own time. His famous study, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (1860), and his surveys of ancient Greco-Roman culture are imbued with a nostalgia for these past societies, which he considered more virtuous, invidiualistic, and original. However, Burckhardt's nostalgic view of the past was not the only facet of his outspoken antimodernism: another (and far more problematic) aspect was his deep-seated antisemitism.Footnote 23 These elements of Burckhardt's thought blend together in the scathing architectural critique that he offered of his visit to Frankfurt am Main, a leading center of commerce and bourgeois culture at the time:

Furious building of palaces by Jews and other company promoters, and what is more, in German Renaissance, which our friend Lübke has made the fashion. Clumsy ornamentation of every description, naturally, has been smuggled in under that rubric; people who are incapable of producing something beautiful are unable to do so whatever the style, and all the “motives” and “themes” in the world don't help a man without fantasy. Most of what is built in Italian Renaissance is hideous, despite its richness, e.g., huge windows framed by projecting pilasters and pediments without any attempt at a pedestal. And you should see the classical buildings!

The wealthy Israelites

Build with Caryatids

which must show up to good advantage when Kalle and Schikselchen and Papa, with their famous noses, appear on the balcony between the females borrowed from the Pandroseion.Footnote 24

We do not know which particular villas Burckhardt had in mind. Frankfurt am Main was home to one of the largest and most prosperous Jewish communites in the German Empire, and it certainly did not lack stately residences owned by Jews. The massive destruction of World War II makes it difficult to link Burckhardt's observations to specific buildings.Footnote 25 That said, Burckhardt's critique was never just about individual cases; it was about what he considered a general problem of his time: “People who are incapable of producing something beautiful are unable to do so whatever the style.” This, of course, was a classic trope of nineteenth-century racial antisemitism. It had been forcefully promoted by the composer Richard Wagner, Burckhardt's contemporary and author of the infamous treatise Jewry in Music (1850/1869). There, Wagner apodictically declared, “Our entire European civilization and art has remained a foreign language for the Jews … In this language, the Jew can only imitate and recreate, but not express himself with genuineness or create works of art.”Footnote 26 Burckhardt had a low opinion of Wagner's music, but both men shared the view that Jews lacked true artistic understanding and creativity.

One might wonder whether these prejudices are also present in Woltmann's architectural critique of Berlin's “caryatid luxury.” As we have seen, Woltmann speaks of a “pursuit of glamor and wealth” that forces the Hellenic maiden to “serve the needs of private luxury and to carry out quotidian labor.” Some of the language here was ambiguous enough to resonate with the vocabulary of nineteenth-century antisemitism.Footnote 27 This includes the trope of relentless greed for profit and ostentatious display of wealth. The accumulation of riches follows the same logic of exploitation that characterizes the facade design: just as the rich capitalist creates dependencies that force ordinary people to render him services and profits, so does he “degrade” the caryatids on the exterior of his home to display his wealth. A further element of this critique that was potentially open to an anti-Jewish interpretation is the allegation of superficiality: Woltmann speaks of “pleasant details and clever execution,” but no “overall effect.” Burckhardt, we recall, decries the “building of Palaces by Jews” as an architecture of “clumsy ornamentation” (plumpes Zeug). Here again, there is overlap with Wagner's influential treatise that claimed that Jewish aesthetics was always about appearance, not substance, and that the artistic achievements of Jews were based on hollow imitation rather than genuine understanding.

There were, to be sure, legitimate grounds for criticizing nineteenth-century historicist architecture as an architecture of appearances. But there was no reason—other than prejudice—to link this critique to a supposed “Jewification” (Verjudung) of society.Footnote 28 If anything, it was new production methods that accounted for the proliferation of caryatids: from the mid-nineteenth century onward, most caryatids were created by means of mass production, not through the painstaking work of individual sculptors as in years past. In particular, the new method of zinc casting, together with factory-scale use of terracotta and plaster, allowed for production of statues in large quantities. Architects could order any number of caryatids off the shelf and place them freely in their architectural designs.Footnote 29

The wholesale insertion of caryatids into facades must have seemed out of place in the case of large apartment buildings (also known pejoratively as “rental barracks,” or Mietskasernen in German). There, the embellishment of the exterior often covered up the rather modest conditions in the interior—a kind of facade architecture that benefited developers more than tenants.Footnote 30 In the case of the rental barracks, the desire to display familiarity with ancient culture had clearly given way to ornamentation for its own (and for profitability's) sake.Footnote 31 A general critique of the proliferation of caryatids could have built on this observation. But this was not Burckhardt's concern. The issue that disturbed him was social as much as it was aesthetic: he took offense at the social and economic rise of Jewish families—parvenus, in his view—who had the chutzpah to appropriate architectural traditions to which they had no instrinsic claim or connection. In Burckhardt's opinion, this ostentation was the symptom of a society in which money could buy everything—a view very similar to Wagner's argument that, for the Jews, “our modern body of knowledge [Bildung] … has decayed into purchaseable luxury goods.”Footnote 32 For Burckhardt, the fundamental illegitimacy of this cultural appropriation was blatantly visible and racially determined: beside the Greek maidens with their gracious, well-proportioned bodies, the Jewish residents would stand on the balcony, displaying the full extent of their physical “ugliness” and bodily deformation (“their famous noses”).

Caryatids and Jewish Self-Fashioning: The Case of Vienna

For anyone familiar with the stereotypes of nineteenth-century racial antisemitism, the elements of this discourse are hardly suprising.Footnote 33 The more interesting (and also more complicated) question is what nineteenth-century Jews saw in the caryatids that adorned their residences. Were the statues mere ornaments, or did they serve as a surface for the projection of Jewish identity?

In no other European city can this question be more fruitfully explored than in Vienna—the veritable caryatid capital of nineteenth-century Europe.Footnote 34 After the construction of the Ringstraße boulevard in the 1860s, caryatids were everywhere in Vienna: in the interior of buildings (for example, the famous gilded caryatids of the Musikverein concert hall, 1867–1870) as well as on the outside (such as at the entrances of the Austrian parliament building, 1874–1883). Caryatids also populated the facades of the prestigious private residences that sprouted up along the famous ring road—including the residences of Vienna's Jewish elite.Footnote 35

One of the earliest and most influential Jewish residences of this type was the Palais Todesco (1861–1864), commissioned by the rich textile industrialist and banker Eduard von Todesco. (See figure 4.) Located across the street from the city's iconic opera house, the palais was designed by Ludwig Förster, a leading Viennese architect who had been involved in the master plan for the Ringstraße. At first sight, the Palais Todesco with its imposing Neo-Renaissance facade blends seamlessly into the style of the other historicist residences along the boulevard. A closer look, however, reveals subtle references to the owner and his religious background.

Figure 4. Ludwig Förster, Palais Todesco, Vienna, 1861–1864. Historical photograph by Hermann Heid, ca. 1875. (Image: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam)

Now largely forgotten, Todesco was one of the most prominent Viennese Jews of his time. Although elevated to the nobility by imperial decree, he remained a Jew throughout his life. He certainly also remained a Jew in the public eye: among the city's elite and in the popular press, Todesco was depicted as a Jewish parvenu and mocked for his occasionally incorrect use of foreign words.Footnote 36 Yet Todesco, like so many European Jews in this period, did not give up the hope of maintaining a Jewish identity while also achieving general acceptance in the majority society. An active member of Vienna's Jewish community, he donated to Jewish philanthropic causes just as generously as he supported gentile charities.Footnote 37

Todesco's aspiration to gain respectability and remain true to his faith also left an imprint on the design of his palais. Instead of leaving the planning process entirely to his acclaimed Christian architect, Todesco got involved in minute details, including the design of the caryatids. In total, twenty-six caryatids adorn the palais's exterior: eighteen on the top floor of the main facade, and four on each side facade. One caryatid on the main facade is particularly noteworthy because she displays the Star of David in her tiara. (See figure 5.) Barely visible from street level, this small but symbolic detail might suggest a reference to the biblical Jewish queen Esther, who, through her courage, wisdom, and virtue, rescued the Jewish people from great danger. Another caryatid appears with covered hair, holding a book in her hand—a pose without ancient precedent and, it seems, a more general reference to the qualities of a devout Jewish woman.Footnote 38

Figure 5. Caryatid with a tiara featuring the Star of David. Palais Todesco, Vienna. (Image: Courtesy of Benjamin von Radom)

On a concrete level, these “Jewish” caryatids also alluded to the lady of the house: Sophie von Todesco, the banker's wife and a woman commited to a range of social and cultural causes. Sophie helped run her husband's literary club, but she earned particular renown for her regular salon, which, in the great tradition of nineteenth-century Jewish salonnières, was open to Jews and Christians alike. In many ways, Sophie played a pivotal role in complementing the family's economic capital with social and cultural capital. Her husband acknowledged this in the iconographic program of the facade: the details of the two “Jewish” caryatids pay homage to Sophie von Todesco as an exemplary Jewish “woman of valor” and, as it were, a modern Queen Esther.Footnote 39

Representations of Queen Esther as a female role model were not uncommon in Jewish visual culture at the time, including in the decoration of upper-class Jewish residences. The Palais Ephrussi (1872–1873), home to another wealthy Viennese-Jewish banking family, featured in its ballroom a series of wall paintings with scenes from the life of Esther.Footnote 40 The Palais Ephrussi also boasted an impressive assembly of caryatids on its facade. (See figure 6.) Edmund de Waal, a descendant of the family, has vividly described the impression that this gallery of caryatids still makes today: “There are so many of these massive, endlessly patient Greek girls in their half-slipped robes—thirteen down the long side of the Palais on the Schottengasse, six on the main Ringstrasse front—that they look a little as if they are lined up along a wall at a very poor dance.”Footnote 41 It is true that the Ephrussi caryatids do not display any discernable Jewish attributes. Still, there is evidence that, in the eyes of some Jewish contemporaries, even generic “Greek girls” evoked assocations with the qualities of Jewish women. As late as 1916, Vienna's chief rabbi, Moritz Güdemann, proclaimed: “Who does not know the caryatids who, on the façades of palaces, carry heavy loads on their shoulders? The Greeks invented these female figures, but Jewish women realized them in life.… The biblical poet sang of these women: ‘A wife of noble character who can find? She is worth far more than rubies.’”Footnote 42

Figure 6. Theophil von Hansen, Palais Ephrussi, Vienna, 1872–1873. Historical photograph by Michael Frankenstein, ca. 1880. (Image: Wien Museum, Vienna)

This discourse might also illuminate the specific design of the caryatids in another Jewish Ringstraße residence: the Palais Epstein (1868–1871). Its owner, Gustav von Epstein, had made a fortune as an industrialist and banker, not unlike Todesco. Indeed, Epstein admired the slightly older Todesco and followed his footsteps as a patron of the arts and supporter of charitable causes.Footnote 43 Epstein also served on the executive council of Vienna's Jewish community. When he decided to build a stately residence for his family, Epstein commissioned the architect Theophil Hansen, the partner and son-in-law of Ludwig Förster (who had designed the Palais Todesco). Both palais indulge in the same lavish Neo-Renaissance style, but the Palais Epstein gained a unique reputation in Vienna because it was built on the most expensive plot along the Ringstraße. From the very beginning, Epstein's palais was a bold personal statement, and its carefully planned design reflected that. The details of the interior and exterior decoration formed the subject of long deliberations between the architect and his client.

Following Todesco's model, Epstein went to great lengths to invoke the legacy of ancient Greek culture, including in elaborate interior wall paintings that depicted scenes from Greek mytholology. As Elana Shapira has argued, such images were not only meant to display familiarity with ancient culture, but also aimed to present the elite Jewish owners as worthy heirs of the urbane Hellenistic Jews.Footnote 44 Unsurprisingly, this palais, too, featured caryatids on the exterior—and as in the case of the Palais Todesco, their design was peculiar. (See figure 7.) The architect's early sketches had envisioned caryatids with a gracious, maiden-like touch, but Epstein expressed his preference for a set of caryatids with a more robust appearance. Executed by the Czech sculpture Vincenz Pilz, the four large caryatids at the entrance are not embedded into the facade, instead protruding into the public sidewalk. Whether Epstein intended the caryatids to express homage to Jewish women is debatable. It is certainly true that the bold caryatids at the portal display the same self-confidence that was a defining trait of Epstein's personality and also underpinned the Latin motto of his coat of arms, prominently inscribed in the palais's entrance hall: Sis qui vederis (Be who you appear to be).Footnote 45

Figure 7. Vincenz Pilz, Caryatids at the entrance of the Palais Epstein, Vienna, 1868–1871. Architect: Theophil von Hansen. (Image: Markup, CC-0, via Wikimedia Commons)

For antisemites, such statements of self-confidence were a provocation. In this regard, the case of Vienna is not unique. Consider Ferrières, the lavish château that Baron James de Rothschild built for his family outside of Paris in the late 1850s. Its central hall features a quartet of life-size caryatids and atlantes, each carrying a globe, symbolizing the four continents in which the Rothschild business empire operated.Footnote 46 A modern visitor would find the racial imagery problematic (the caryatids are Black), but for antisemitic viewers at the time, it was the underlying confidence that stood out as the real affront. When, in 1870, the Prussian army captured Ferrières, the army preacher Bernhard Robbe visited the château and remarked on the caryatids as contributing to the “showy impression” (protzigen Eindruck) that turned this Rothschild residence into a “synagogue bristling with gold” (goldstrotzende Synagoge).Footnote 47

There were, to be sure, contemporaries of Jewish origin who lambasted the Jewish upper class for what they considered tasteless ostentation. Among these, in Vienna, was Karl Kraus, the feared satirist who had formally left Judaism in 1899. In his scathing essay “He's Only a Jew After All” (1913), Kraus renounced all ties to his former correligionists, claiming that their commitment to capitalism was greater than their loyality to the state, and declaring that he was not interested in interactions with social upstarts and “speculators.”Footnote 48 Kraus argued that Austria needed to defend itself against the exponents of an unfettered capitalist materialism, comparing the state to a naive “homeowner who holds a lamp for the burglars—but look, at least the caryatids at the front still belong to him!”Footnote 49 The reference here was likely to the caryatids at the entrance to the Austrian parliament, a building adjacent to the Palais Epstein. Figuratively, Kraus suggested that Jewish speculators, through ruthless financial operations, had become so rich that they did not even need to steal the commonwealth's caryatids.Footnote 50 Kraus wrote with his typical quantum of sarcasm, and his personal relation to Judaism is as complex and contrarian as is his deployment of antisemitic tropes (which occasionally went hand in hand with a critique of what he considered an “inferior” kind of antisemitism).Footnote 51 Still, the underlying point here—the reduction of caryatids to a mere, commodified facade element—resonates with Burckhardt's remarks about rich Jews and their ostentatious “building of Palaces” or Rogge's remark about the Rothschild “synagogue bristling with gold.”

“Caryatid Peoples”: The Genealogy of a Trope

At the same time, there were other, positive responses to the taste for caryatids that characterized so many Jewish upper-class residences. This brings us back to Walter Benjamin, who reflected, with great nostalgia, on this common feature of the bourgeois cosmos in which he grew up. In his Berlin Chronicle, Benjamin called the caryatids a key element in the “first chapter of a science of this city.”Footnote 52 In the opening section of the final version of “Berlin Childhood around 1900,” he elaborated:

For a long time, life deals with the still-tender memory of childhood like a mother who lays her newborn on her breast without waking it. Nothing has fortified my own memory so profoundly as gazing into courtyards, one of whose dark loggias, shaded by blinds in the summer, was for me the cradle in which the city laid its new citizen. The caryatids that supported the loggia on the floor above ours may have slipped away from their post for a moment to sing a lullaby beside that cradle—a song containing little of what later awaited me, but nonetheless sounding the theme through which the air of the courtyards has forever remained intoxicating to me. I believe that a whiff of this air was still present in the vineyards of Capri where I held my beloved in my arms; and it is precisely this air that sustains the images and allegories which preside over my thinking, just as the caryatids, from the heights of their loggias, preside over the courtyards of Berlin's West End.Footnote 53

For Benjamin, the caryatids represented the feeling of protection and comfort that characterized the bourgeois world of his childhood. They played, as it were, a motherly role.Footnote 54 He expressed “greatest affection” for these “dust-shrouded specimens of the race of threshold dweller”—not least because they were “versed in waiting.” Whether it was the young boy returning home from school or the grown man revisiting the scenes of his childhood, he was always greeted by the calm, gracious caryatids at the entrance. “It was,” Benjamin writes, “all the same to them whether they waited for a stranger, for the return of the ancient gods, or for the child that, thirty years ago, slipped past them with his schoolboy's satchel.”Footnote 55

In their stoic patience, the caryatids became mementos of stability—or, rather, of a past promise of stability, for this comfortable, sheltered childhood foreboded “little of what later awaited me.” Benjamin, who, even before 1933, could not obtain a permanent academic position in Germany due to his Jewish origins, was all too familiar with rejection. He was, of course, not alone in this experience. Was not rejection (and the experience of disappointed hopes) a leitmotif in the lives of countless European Jews in this period? The nineteenth century had begun with great expectations—including the hope for complete political emancipation and full social recognition. But even if the former was eventually accomplished, the latter remained out of reach in many places. Perhaps, then, one can compare the state of Jews in nineteenth-century Europe to the state of caryatids. Both caryatids and Jews were “versed in waiting” (to adopt Benjamin's words). Both carried a heavy burden, yet were bound to remain on the outside: the caryatids populating the exterior of fin-de-siècle buildings formed a “race of threshold dwellers,” just as the Jews remained on the threshold of social acceptance and never gained full admission to the inner sanctum of society.

Ludwig Börne, the controversial German-Jewish critic, may have intuited this as early as the 1820s. In his collected aphorisms, Börne spoke of the “political caryatids” (politischen Karyatiden) of his time: it appears “as if they carry on their shoulders the weight of the entire building that is the state,” but in reality, they “are nothing but the lowest parts of that building.”Footnote 56 Almost a century later, the analogy between Jews and caryatids was spelled out explicitly by Jacob Wassermann, the popular German-Jewish novelist and public intellectual. Early in his career, he moved to Vienna, where he had plenty of opportunities to observe the proliferation of caryatids along the Ringstraße and its upper-class Jewish residences. In Wassermann's novel The Jews of Zirndorf (1897), the mansion of the Jewish banker Baron Löwengard features caryatids that “patiently carried the weight of the balcony.”Footnote 57 For Wassermann, caryatids were not simply a typical feature of upper-class Jewish homes, but symbols of the Jewish condition in general. In his autobiography My Life as German and Jew (1921), he reflected, with deep resignation, on the ultimate failure of German Jews to become fully accepted members of society. Wassermann emphasized that German Jews had gone out of their way to gain recognition and equal footing; they had also supported the greatest minds of the nineteenth century; and yet they remained subordinated like caryatids:

[The evidence of this Jewish support can] be found by examining the careers of the men who embodied the innovative and creative forces of the nineteenth century, it may be found in letters, sometimes in casual, sometimes very veiled comments, in the first fresh judgment of their contemporaries, in the shapers and carriers of public opinion. Jews were their discoverers and their receptive audience, Jews proclaimed them and became their biographers, Jews have been and still are the caryatids of almost every great name [die Karyatiden fast jeden großen Ruhms].Footnote 58

This experience of cultural subordination and social outsiderdom was not exclusively Jewish. From a völkisch standpoint, every individual or group that was not purely “Germanic” remained inferior, including the Slavic peoples of eastern Europe. In an 1861 poem that celebrated the Prussian king and called for a new German empire under his leadership, the German-Austrian author Friedrich Hebbel coined the trope of “caryatid peoples” and depicted them as a threat to the imperial project:

Hebbel, to be sure, was not a radical nationalist; in fact, on some political issues of the day he expressed rather liberal views. Yet his depiction of eastern European peoples as uncultured caryatids—who, he went on, were bound to go extinct in the future—was a most dangerous political statement.Footnote 60 Unsurprisingly, Hebbel's poem met with fierce criticism among Czech and Polish contemporaries.Footnote 61 By contrast, in German nationalist circles, Hebbel's image remained popular beyond his days, not least so in the multiethnic Austrian empire, where tensions between German and Slavic communities were deeply entrenched and regularly led to social and political conflicts.Footnote 62

Is it a coincidence that the Austrian parliament, built between 1874 and 1883, prominently featured caryatids on the exterior as well as in the interior? For the architect, Theophil Hansen, the caryatids may have been a mere homage to ancient Greek political culture, but in the charged political atmosphere of a multiethnic empire, the caryatids could be construed as a statement about imperial hegemony and the need to submit to it.Footnote 63 Austria's parliament certainly became a forum for those German nationalist agitators who, in the spirit of Hebbel's poem, regarded certain ethnic communities, such as the Slavs, as inferior “caryatid peoples.” Jewish observers sensed that such agitation against ethnic groups could easily extend to religious minorities.Footnote 64 Thus, an Austrian-Jewish newspaper commented in 1896:

Especially here in Austria the nationalist rabble-rousing creates an atmosphere that is most dangerous for us Jews. When, in the Chamber, a German member of parliament is allowed to speak of the Czechs as ‘shaggy caryatid-heads,’ … why should ordinary German citizens think differently of us Jews, and why should they treat us differently? This nationalist battle leads to such a coarsening that the the fighting parties, in their desire to gain the support of the masses, resuscitate humanity's immortal beastliness, shouting the old [antisemitic] Hep-Hep cry that has never failed its effect because even the dumbest person understands its message.Footnote 65

Nationalist and antisemitic agitators were hardly impressed by such arguments. In fact, they added insult to injury and weaponized the caryatid metaphor even further: if Jews were caryatids among the Germans, they were at the same time the masters of the inferior peoples of the East. In other words, the Jews, unrelenting capitalists and profiteers, exploited the Slavs economically, as “the forces of Jewish power” in Poland and Russia sought to turn the “native populations [of the East] into caryatids in the building of Jewish rule.”Footnote 66 The perverse logic of antisemitism is obvious here: the Jews are always guilty.

Caryatids Set Free: Zionism and the Aesthetics of National Liberation

It is this odious irrationality of antisemitism that led to Jacob Wassermann's bitter conclusion that one could be either Jewish or German but not both. But there were others in the Jewish community who reacted differently. The alternative response—the Zionist response—was a call for complete Jewish emancipation: not the political emancipation of the nineteenth century, with its aim of absorbing Jews into the “building that is the state” (Börne's words), but rather emancipation in the sense of national independence. This, of course, was the vision that Theodor Herzl, the founder of political Zionism, formulated in this period. Herzl, a playwright and leading journalist of fin-de-siècle Vienna, had personally experienced antisemitic discrimination at various stages of his life. His journalistic coverage of the Dreyfus trial in Paris in the 1890s contributed to his abandonment of earlier hopes that acculturation—or even mass conversion—would resolve the problem of antisemitism. From 1896, with the publication of his manifesto The Jewish State, Herzl spared no effort to establish a national Jewish home in Palestine.

In 1898, Herzl undertook his first and only journey to the Holy Land, joined by a small group of his closest allies. The goal was to meet German Emperor Wilhelm II during his state visit to Palestine and to convince him of the legitimacy and urgency of the Zionist plans. On the way to Palestine, the ferry that carried Herzl and his fellow delegates made a routine stop in the Greek port of Piraeus. The passengers had only a few hours for a shore leave. The travel party decided to use the time for a tour of nearby Athens and its famous Acropolis. Only one picture of the outing survives. (See figure 8.)

Figure 8. Herzl and the other members of the Zionist delegation in front of the Erechtheion, Athens, October 1898. (Image: The Herzl Museum, via Wikimedia Commons)

Why did the Zionist travelers choose to have their picture taken in front of the Erechtheion and not, say, the more imposing Parthenon? The photograph—the only one taken on the Acropolis—was undoubtedly a souvenir, but not a random snapshot. Herzl was keenly aware of the power of images and made sure that key moments of the journey were visually chronicled, rightly anticipating the wide circulation of these pictures in Zionist circles. The visit to the Acropolis was one such special moment, even if Herzl later admitted feeling underwhelmed. In his diary, he noted, “Up through the dust to the Acropolis, which likewise says so much to us only because classical literature is so powerful. The power of the word! Then raced through Athens in a matter of minutes, but that seemed enough for the modern city.”Footnote 67 A slightly more detailed account of the visit comes from one of his companions on the journey, Max Bodenheimer: “What a pleasant and moving sight met our eyes! The Parthenon like a symbol of calm grandeur rising on a wide, marble-paved square and next to it, like an idyll, the Erechtheion and its charming annex with the caryatids.”Footnote 68 Even this account—a personal pastiche of Baedeker and Winckelmann—does not suggest that the visit to the Acropolis was the kind of epiphanic moment depicted in later Zionist hagiography. A little more than a decade after the journey, the Zionist press related that Herzl, standing in the shadow of the ancient ruins, “was so moved that he recited Homeric verses in Greek”—to which David Wolffsohn, another Zionist of the first hour, responded, “These ruins are not ours.” Herzl, initially “hurt” by the remark, eventually embraced this point of view. When the travelers arrived at the Western Wall in Jerusalem, Herzl—or so the story goes—conceded that only monuments of the biblical past could touch the Jewish soul.Footnote 69

We can safely consign this story to the realm of apocryphal legend. For one thing, Wolffsohn's travel diary survives and does not record any such conversation.Footnote 70 For another, we know that Herzl was just as underwhelmed by the Western Wall as he had been by the Acropolis. “A deeper emotion refuses to come,” he noted in his diary in Jerusalem.Footnote 71 In Herzl's eyes, both the Western Wall and the Acropolis were sites of past glory. He was far more captivated by the monuments of modern innovation. During his short stay in Egypt, he noted, “At Port Said I greatly admired the Suez Canal. The Suez Canal, that shimmering thread of water stretching away toward infinity, impressed me much more than the Acropolis. Human lives and money, it is true, were taken and squandered on the Suez Canal, but yet one must admire the colossal will that executed this simple idea of digging away the sands.”Footnote 72

This admiration for the Suez Canal fit into Herzl's vision of the mission of Zionism, another movement of “colossal will”: the Jews should become dynamic men of action, emancipated from the powerlessness of the past and from the subordination to other nations. In other words, not a “people of caryatids” in the heart of Europe, but rather a modern, innovative nation that would Europeanize the Near East. Indeed, Herzl firmly believed that the Jewish civilizing influence would help to liberate the Near East from the culture of servility and inertia that he considered deeply ingrained in Ottoman society. During his audiences at the Ottoman court in Constantinople, Herzl wrote dismissively of the corrupt “baksheesh caryatids” (Bakschisch-Karyatiden) who populated the sultan's court.Footnote 73

Against this backdrop, we might gain a better understanding of Herzl's choice to have a group photograph taken at the Erechtheion. The picture shows five determined Zionist men posing in front of the five surviving statues of women who, according to the Vitruvian tradition, had abandoned their own people and paid for it with captivity. In this stark contrast, the Erechtheion formed a fitting background for Herzl to present himself as a man of action and liberator of his diasporic people. Herzl, we should recall, was a theaterman turned politican, and scholars have long noted that a sense of operatic theatricality imbued his Zionist vision.Footnote 74 Much less explored, however, is Herzl's deep fascination with architecture as both art and political allegory. Just a few weeks before his journey to Palestine, during the preparations for the second Zionist Congress in Basel, Herzl made architectural sketches in his diary and noted, “The art form which is most meaningful to me now is architecture. Unfortunately, I don't command its means of expression. If I had learned anything, I would be an architect now.”Footnote 75 Instead, as is well known, Herzl devoted himself to becoming the architect of a state.

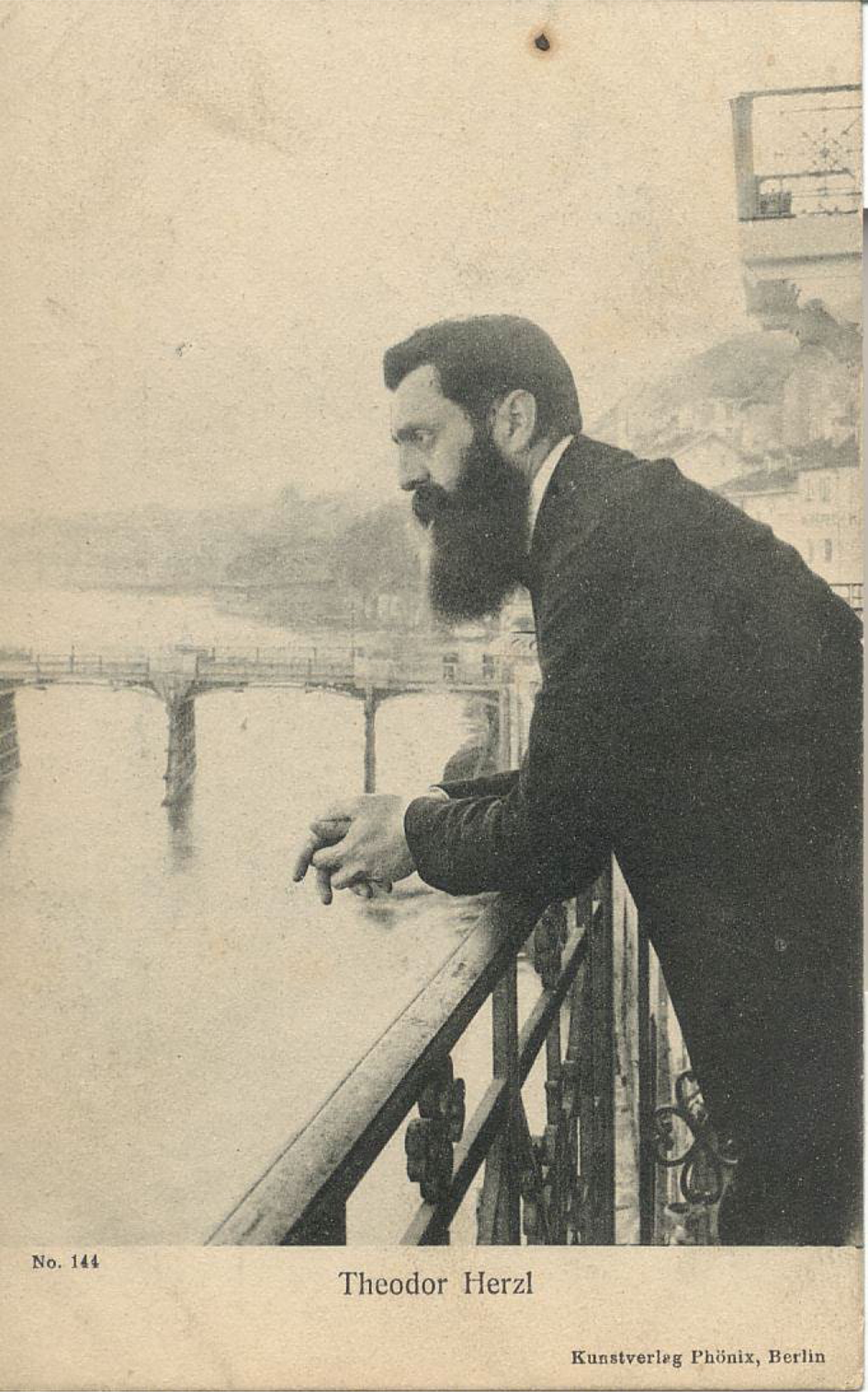

Herzl underestimated the burden that came with state-building. At the time of his early death, at the age of forty-four, he was exhausted from tensions within the Zionist movement, continuous financial problems, and the political opposition of major European powers. He aspired to redeem the Jews from their caryatid-like status, but he did not anticipate that he was taking on a task as heavy as the weight on Atlas's shoulders. In lighter moments, Herzl liked to joke that he was quite literally an Atlas in that he had chosen to found and edit a Zionist newspaper by the name Die Welt: the general editorship of this “world” rested entirely on his shoulders.Footnote 76 The toll that the self-imposed mission took on Herzl was also not lost on contemporary observers. Perhaps the most famous portrait of him reflects this: taken during the Fifth Zionist Congress in Basel (1901), E. M. Lilien's photograph shows the Zionist leader standing on the balcony of his hotel overlooking the Rhine. (See figure 9.) The photograph, officially approved by Herzl, has often been described as the portrait of a visionary immersed in his thoughts.Footnote 77 The Basel portrait was certainly conceived, and perceived, as a heroic portrait, but it also hints at the magnitude of his task: there is none of the bodily strain of Atlas (see figure 2), but his head and chest are bent forward, under figurative weight. The widely circulating Herzl portrait by Hermann Struck evoked similar associations (See figure 10.) As Max Bodenheimer, Herzl's staunch supporter, records, the etching “represents [Herzl] as a kind of Atlas, on the point of breaking down under the weight on his shoulders of his tormented people.”Footnote 78 After his death, Herzl was widely eulogized as an “atlas” who had carried an immense burden and “died as a martyr” so that his fellow Jews with their “crooked backs” could walk upright again.Footnote 79

Figure 9. Ephraim Moses Lilien, Theodor Herzl during the Fifth Zionist Congress in Basel in 1901, overlooking the Rhine from his balcony at the Hotel Les Trois Rois. Postcard 1901. (Image: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Figure 10. Hermann Struck, Portrait of Theodor Herzl. Etching, 1903. (Image: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Caryatids, Atlantes, and the Burden of Modern Outsiderdom

Interestingly, some Jewish Hellenistic authors identified the Greek mythological figure of Atlas with the patriarch Enoch from the Hebrew Bible.Footnote 80 But it is doubtful that Herzl and his admirers were aware of this tradition. For them, the (self-)identification with Atlas formed, more than anything else, part of the romantic cult of artistic genius. Herzl chose the path of politics after his ambitions as a writer had been frustrated. Other nineteenth-century artists, faced with similar frustrations, embraced rejection and adhered to the notion that artists were individuals bound to be misunderstood or unrespected by their environment. From this perspective, the romantic artist-genius was destined to be an “unhappy Atlas” (in Heinrich Heine's famous words, set to music by Franz Schubert).Footnote 81

In this discourse, Atlas served as a prototype of an aesthetically sublimated yet distinctly masculine experience of suffering and outsiderdom. Still, atlantes and caryatids could also be construed as interchangeable embodiments of the same condition. As we have seen, scholarly authorities such as Winckelmann had declared caryatids and atlantes to be part of the same genre. While the Atlas motif invited a particular kind of male self-identification and lament, the caryatid lent itself to an expression of collective powerlessness and stoic endurance. In this context, the trope of certain peoples as subjugated “caryatid peoples” formed a structural counterpart to the traditionally female represesentations of strong nationhood, as embodied by unfettered female heroine-figures such as Germania, Marianne, or Britannia.

These rich symbolic connotations, taken together, help to explain why both atlantes and caryatids emancipated themselves in nineteenth-century art—not, to be sure, from the stone that they must carry, but from a solely architectural function. Unprecedented in the long reception history since antiquity, atlantes and caryatids began to appear as freestanding sculptures.Footnote 82 In the case of the caryatids, this development is particularly salient in the influential sculptures of Auguste Rodin. The French sculptor created caryatids in a wide range of different materials, such as bronze, marble, and plaster. In Rodin's art, the caryatid embodies the experience of modernity as one of suffering, rejection, and isolation, but it also suggests endurance as the only possible response to the weight of conventions and to the overpowering forces of society. The caryatid, in other words, has become a psychological motif.Footnote 83

Did this motif have a particular appeal to Jewish artists—dual outsiders, as they were, by profession and religion? Prominent names come to mind. Consider, for instance, Amedeo Modigliani, in whose sculptural work and drawings caryatids make frequent appearances. Of his caryatid drawings alone, more than seventy are known.Footnote 84 (See figure 11.) Modigliani, an Italian Jew living in Paris, felt a deep connection to his Jewish heritage, considering it an essential part of his lived outsiderdom as an artist, bohemien, and foreigner. Even in the most ordinary social interactions, Modigliani sometimes proudly introduced himself with the words, “I am Modigliani, a Jew” (Je suis Modigliani, juif).Footnote 85 At the same time, he did not fail to notice the rise of racial antisemitism, especially after his move to Paris in 1906. One of his artist friends recounts episodes of resignation: when Modigliani was asked, “So, it's wretched to be a Jew?” he replied, “Yes, it's wretched.”Footnote 86 Based on such biographical evidence, some art historians have argued that in Modigliani's work “the inability of Jews to escape their condition … is given literal, formal, and symbolic expression: literally, in the case of the caryatid locked in its column.”Footnote 87

Figure 11. Amedeo Modigliani, Caryatid. Watercolor, ca. 1913. Amy McCormick Memorial Collection 1942.462, Art Institute Chicago. (Image: Art Institute of Chicago)

One could also think of the Russian-Jewish architect Berthold Lubetkin who, like Modigliani, lived as a foreigner abroad: in 1931, Lubetkin left the Soviet Union and emigrated to England, where he joined the relatively small community of modernist architects there. Lubetkin was known for his clear, geometrical formalism in the spirit of the International Style—a commitment to modernism that earned him the praise of Le Corbusier and other leading avant garde architects. It seems all the more surprising that, in his London apartment complex Highpoint II (1938), Lubetkin furnished the entrance portal with two life-size caryatids. (See figure 12.) The statues appear to carry the canopy, but in reality they have no structural function.Footnote 88 Why, then, did Lubetkin choose to insert the caryatids—a historicist element that seems completely at odds with the rest of the sober, unemotional design of the building? As architectural historian Deborah Lewittes has noted, in the modernist setting of Highpoint II, the caryatids were “far from rational and far from an earnest return to a safe, historical style.”Footnote 89 Although they served no load-bearing function, they still carried a symbolic meaning: in Lewittes's convincing interpretation, the caryatids signaled “a vocal response to the demand to be quiet, both as a Jew and as a modernist, in a society that hated both.”Footnote 90

Figure 12. Berthold Lubetkin, Caryatids at the entrance to Highpoint II, London 1938. (Image: Photo by Leo Eigen. Used with permission.)

The appearance of the caryatid motif in the work of Jewish artists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries deserves further exploration. It forms part of a larger cultural discourse that invoked Greek mythological figures as a structural counterpart for a definition of Jewish identity.Footnote 91 At the same time, such an exploration ought to keep in mind that Jewish artists were not alone in employing the caryatid motif in a creative quest to define and express their place in society. In European art around 1900, various social groups and individiduals invoked caryatids to reflect on the experience of outsiderdom, marginality, or the burdens of modern life. This found expression in visual as well as literary works.Footnote 92 Rainer Maria Rilke, the refined aestheticist and poet, depicted life in the modern metropolis as an unrelenting series of encounters with humans who are mere “ruins of caryatids” (Trümmern von Karyatiden).Footnote 93 His contemporary, the poet Ricarda Huch, described caryatids, in their stoic acceptance of an imposed burden, as distinctive identification figures for the largest group of second-class citizens at the time: women.Footnote 94 Both perspectives coalesce in what is perhaps the most important literary treatment of the caryatid motif in fin-de-siècle German literature: Gottfried Benn's high-expressionist poem “Caryatid” (1916). Displaying a heavy debt to Nietzsche, the poem calls in a spirit of dionysian exuberance on the enslaved female statues to liberate themselves:

In his later years, Benn, the great nihilist of modern German literature, dismissed the poem as belonging to the “beautiful, pointless, outdated stuff” from his expressionist period.Footnote 96 Indeed, he never revisited the caryatid motif.

By contrast, another writer of this period engaged with the motif throughout his literary career: Franz Kafka. It has rightly been argued that “Kafka's works are teeming with caryatids and atlantes.”Footnote 97 Kafka, to be sure, rarely speaks explicity of such statues, but as early as the 1930s, Walter Benjamin—whose skilled eye for such details we have already observed at work—posited that many figures in Kafka's oeuvre are “descendants of those figures of Atlas that support globes with their shoulders.”Footnote 98 As Benjamin notes, however, “it is not the globe they are carrying; it is just that even the most everyday things have their weight.”Footnote 99 In his analysis, Benjamin points out that “ceilings are almost always low in Kafka” and that they press down on the protagonists.Footnote 100 Benjamin also observes that “among the images in Kafka's stories, none is more frequent than that of the man who bows his head far down on the chest.”Footnote 101

The motif of the individual carrying an outsized burden is captured vividly in “Josephine the Singer, or the Mouse Folk” (1924), one of the last stories that Kafka completed.Footnote 102 Kafka, often the harshest critic of his own work, was unusally pleased with this short story and excluded it from his request that his unpublished work be burnt after his death. Today, the tale of Josephine, the mouse-singer, is considered one of the most important stories from Kafka's late work, but its interpretation remains a subject of debate. Indeed, much in this short tale is enigmatic, including the relation between Josephine and her murine people: on the one hand, Josephine is a selfish diva whose singing is really “just a piping” (361); on the other hand, she gives unique comfort to her fellow mice. As the unnamed mouse narrator relates about his burdened people (363):

Our life is very uneasy, every day brings surprises, apprehensions, hopes, and terrors, so that it would be impossible for a single individual to bear it all did he not always have by day and night the support of his fellows; but even so it often becomes very difficult; frequently as many as a thousand shoulders are trembling under a burden that was really meant only for one pair.

These are the moments when Josephine begins her performance. During these appearances, Josephine, that “delicate creature,” stands before the mouse folk, with her “head thrown back, mouth half-open, eyes turned upwards” (364). It is not a pleasant posture; in fact, the singer gives an almost statuary impression. Still, Josephine carries on with the singing, and even though she overestimates her talent, the performances strike a chord among her fellow mice: “Josephine's thin piping amidst grave decisions is almost like our people's precarious existence amidst the tumult of a hostile world” (367). What happens to Josephine at the end remains unsaid. The narrator reports only that she disappears one day (376):

Josephine, redeemed from the earthly sorrows which to her thinking lay in wait for all chosen spirits, will happily lose herself in the numberless throng of the heroes of our people, and soon, since we are no historians, will rise to the heights of redemption and be forgotten like all her brothers.

Some Kafka scholars have interpreted the story as a parable about artistic life. As a priestess of art—boundless in her artistic ambition yet bound by worldy circumstances—Josephine reminds the reader of the sacerdotal caryatids at the Erechtheion. At the same time, she represents the burden of her people, just as the caryatids came to be seen as representatives of an outcast people. In this vein, one could read the story as a commentary on Zionism—a movement that Kafka followed closely and with great personal interest.Footnote 103 Indeed, the story dates to a period when Kafka entertained the idea of immigrating to Palestine.Footnote 104 If the story is indeed a parable about Zionism, it displays Kafka's ambivalent feelings about this political movement and the ability of individual Jewish leaders—whether Herzl or any of his successors—to end the Jews’ “precarious existence amidst the tumult of a hostile world.”Footnote 105 As Iris Bruce has noted about the Zionist reading of Kafka's late stories, the author “is deliberately countering the demands of the more political Zionists for an identifiable Jewish discourse by creating stubborn antiheroes who struggle valiantly but never reach any goals.”Footnote 106 Josephine, in her caryatid-like willingness to carry the collective burden and to stylize her own sacrifice, is a leader with a mixed record: she tries to rise to the ranks of the “heroes of our people,” but as the narrator notes, “no single individual could do what in this respect the people as a whole are capable of doing” (365). The burden of outsiderdom—after all, no animals are more looked down on than mice—continues to rest on the shoulders of the entire community. If redemption is at all possible, it can only be a collective enterprise.

Yet even Kafka, often depicted as a negative prophet of the twentieth century, could not have foreseen the limits of collective agency in the face of overwhelming hostility. Whatever the Jewish “people as a whole are capable of doing,” it was not enough to counter a radical discourse, increasingly growing in the majority society, that regarded Jews as a subordinate “caryatid people,” or—in the ever-shriller language of racial antisemitism—as a community of pariahs, parasites, and untermenschen. The consequences of this racial language of inferiority and subordination are well known.

***

The nineteenth century had begun with the Jewish dream of emancipation. By 1945, millions had been killed as inferior “subhumans,” and the nineteenth-century “World of Yesterday,” as Stefan Zweig famously called it, lay in ruins. Consider Vienna, a city where it had once been possible for a caryatid's tiara to feature a Star of David. In the war, the caryatids and atlantes of Vienna were reduced to rubble, or else they were left bearing the remains of havocked houses, as captured in the photographs of the Viennese-Jewish artist Henry Koerner, who returned to his howntown as an American GI.Footnote 107 (See figure 13.) In Berlin, too, the “caryatid luxury” of the past lay in ashes: in the words of the Jewish philosopher Edgar Morin, then an officer of the French army, the city had become a “carcass of a metropolis,” an unending series of bombed houses, with “knocked-over and shattered atlantes and caryatids in between them.”Footnote 108

Figure 13. Henry Koerner, Schillerplatz in Ruins. Photograph, 1946. (Image: Permission Henry Koerner Estate)

Where the caryatids of the nineteenth and early twentieth century have survived, they deserve more than just our benevolent antiquarian interest. If we carefully explore the cultural context that gave rise to this now much-reduced “other population,” we might still be able to hear what Benjamin called the “song” of the caryatids. As with Josephine's singing, it is not necessarily a pleasing tune. But in its wistfulness, it can tell us much about this age of “epic burdens” and about the inner tensions and forces that weighed so heavily on it.

Acknowledgments

For comments and feedback, I would like to thank Joseph Leo Koerner, Daniel Merzel, Benjamin von Radom, Larry Wolff, as well as the two anonymous reviewers. Unless indicated otherwise, all translations from non-English sources are mine.