Characteristic syndromes following the interruption of an extended period of pharmacotherapy have been reported for various drugs, including antidepressants. These syndromes can include features of the illness for which the drug was administered, but are not generally thought to reflect relapse of the underlying condition. Many patients miss doses during therapy or stop medication without consulting their physician (Reference DemyttenaereDemyttenaere, 1997); the consequences of interruption or discontinuation of antidepressant treatment could include important clinical sequelae, particularly if effects occur quickly or induce significant discomfort. This study assessed the relative frequency, timing, severity and functional impact of symptoms related to the interruption of treatment with paroxetine, setraline or fluoxetine.

METHOD

Patients

Patients with a history of depression diagnosed by a physician and successfully treated with fluoxetine (20-60 mg), sertraline (50-150 mg) or paroxetine (20-60 mg) were recruited by advertisement and referral at four sites. At entry, patients had been taking medication continuously for at least four months but not more than three years, had no dose changes for the two months prior to study entry, were taking no other psychoactive medications, and had a score of ten or less on the 21-item version of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD-21; Reference HamiltonHamilton, 1967). All patients were medically healthy and underwent physical and laboratory examinations prior to participating. This study was approved by the ethical review board for each site. After the procedures of the study had been fully explained, written informed consent was obtained from each subject prior to entry into the study.

Study design

Following an initial assessment, the study consisted of two five-day periods separated by at least two weeks but not more than four weeks. Under double-blind, order-randomised conditions, all subjects underwent placebo substitution during one five-day period and continued treatment with their usual selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) during the other five-day period. Subjects continued treatment with the SSRI at all other times.

Assessments

Patients completed a 17-item adverse event scale (see Appendix) daily for five days following study entry and during the two blinded periods. Items queried were based on reports from previous studies (Reference Rosenbaum, Fava and HoogRosenbaum et al, 1998). Each item was rated from 0 to 3 (absent, mild, moderate or severe) and scores were reported as the change from the most symptomatic of the five days immediately following study entry. At baseline and at the end of each five-day period, the HRSD-21, the State Anxiety Inventory (SAI; Reference SpielbergerSpielberger, 1983) and a self-rated assessment of social and occupational functioning during the previous four days (see Appendix) were administered. Scores for these assessments are reported for each period as the change from baseline (visit 1). Spontaneous reports of adverse events were also collected at all visits. Supine and standing heart rate and blood pressure were measured at each visit, using an automated monitoring device (Welch-Allyn, Skaneateles Falls, NY).

Laboratory assessments

Screening chemistries, urinalysis and complete blood counts were obtained at the initial visit. In order to determine steady-state and post-interruption plasma drug concentrations, samples were obtained at 18.00 h on the fifth day of each blinded period. Drug assays were performed by commercial laboratories (fluoxetine: Oneida, Whitesboro, NY; setraline and paroxetine: MedTox Laboratories, St Paul, MN).

Statistical analysis

We conducted analyses comparing the blinded periods (placebo interruption v. continued active medication) within each medication group. These analyses were based on a crossover analysis of variance with sequence, patient within sequence, period (one or two) and interruption (present or absent) factors in the model. If the crossover effect was statistically significant at a level of 0.10, the interruption effect was based on the analysis of first period results only. Confidence limits were constructed using the least-squares means and associated standard errors from the analysis of variance. Analysis of total adverse events was based on logarithmic transformation of the data because of non-constant variance (heteroscedasticity). Confidence limits for total adverse events were constructed using the non-parametric method of Hodges & Lehmann (Reference Hodges and Lehmann1963). Within-group comparisons of binary measures were performed using Prescott's (Reference Prescott1981) test.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Thirty-seven of 39 enrolled patients treated with fluoxetine, 34 of 36 treated with sertraline and 36 of 44 treated with paroxetine completed both blinded periods. Patients were similar in age, gender distribution, length of current episode of SSRI treatment and baseline symptom severity measures. Patient characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1 Baseline demographics and symptom measures of patients who completed the study

| Demographic or symptom measure | Fluoxetine (n 37) | Sertraline (n 34) | Paroxetine (n = 36) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, mean (s.d.)) | 40.0 (11.4) | 38.7 (14.5) | 39.9 (11.1) |

| Female (n (%)) | 28 (75.7%) | 26 (76.5%) | 22 (61.1%) |

| Mean dose (mg/day, mean (s.d.)) | 29.2 (13.0) | 89.7 (34.2) | 25 (8.8) |

| Duration of therapy in months (30 days/month) (mean (s.d.)) | 12.1 (8.8) | 13.5 (11.2) | 15.9 (10.4) |

| HRSD-21 total score (mean (s.d.)) | 5.4 (2.6) | 5.2 (2.7) | 5.4 (3.0) |

| State Anxiety Inventory total score (mean (s.d.)) | 30.5 (8.7) | 30.6 (9.4) | 29.9 (7.8) |

| Self-assessment scores (Appendix) (mean (s.d.)) | |||

| Work impairment | 1.14 (0.35) | 1.32 (0.59) | 1.43 (0.65) |

| Work missed | 1.05 (0.23) | 1.18 (0.58) | 1.23 (0.65) |

| Relationships | 1.30 (0.52) | 1.47 (0.61) | 1.51 (0.70) |

| Social activities | 1.24 (0.60) | 1.26 (0.67) | 1.31 (0.63) |

| Overall function | 1.54 (0.56) | 1.82 (0.72) | 1.71 (0.71) |

Symptom measures

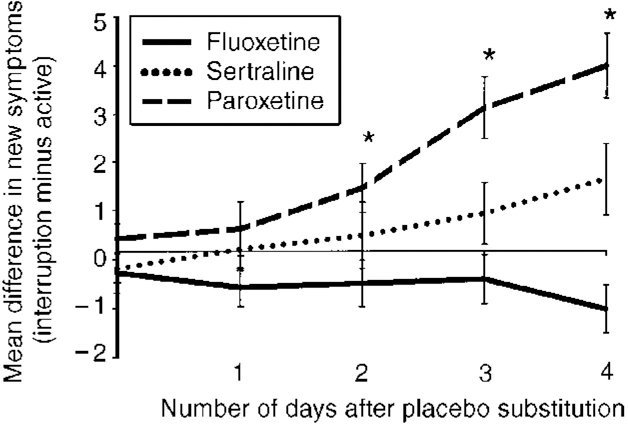

Placebo substitution, but not continued active medication, was associated with statistically significant increases in total numbers of solicited adverse events for patients treated with paroxetine but not those treated with sertraline or fluoxetine, by the end of the fourth day (Table 2). Increases in symptoms for patients treated with paroxetine became statistically significant as early as the time of the second dose of placebo (Fig. 1). Mean severity worsened by the end of the fourth day of placebo substitution for 13 of the 17 items on the solicited adverse events scale among patients treated with paroxetine, for three out of 17 among patients treated with sertraline, and for no items among patients treated with fluoxetine. Among patients taking paroxetine, mean severity of most items increased by between 0.5 and 1 on the four-point scale. For both paroxetine-treated and sertraline-treated patients, dizziness was the item with the greatest number of patients reporting an increase in severity (percentage of paroxetine patients worsening: active treatment 5.7%, placebo 57.1%, P<0.001; percentage of setraline patients worsening: active treatment 6.1%, placebo 42.4%, P=0.002). Patients taking paroxetine also experienced statistically significantly worsened severity in nausea, unusual dreams, tiredness or fatigue, irritability, unstable or rapidly changing mood, difficulty concentrating, muscle aches, feeling tense, chills, trouble sleeping, agitation and diarrhoea during placebo substitution reactive to active treatment. Patients treated with sertraline experienced statistically significantly worsened severity in dizziness, nausea and unusual dreams during placebo substitution relative to active treatment. Spontaneously reported adverse events followed a pattern similar to that of solicited events, with increases for patients treated with paroxetine in dizziness (placebo substitution 33.3%, active treatment 0.0%; P<0.001), headache (placebo substitution 27.8%, active treatment 5.5%; P=0.008), nausea (placebo substitution 16.7%, active treatment 0.0%; P=0.031) and anxiety (placebo substitution 16.7%, active treatment 2.8%; P=0.025).

Fig. 1 Time to onset of symptoms. (Within-treatment changes: *paroxetine: P<0.001 at days 2, 3, and 4.)

Table 2 Mean changes in symptoms during interrupted and continued drug therapy

| Assessment | Fluoxetine | Sertraline | Paroxetine | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interrupted (mean (s.d.)) | Active (mean (s.d.)) | Mean difference (95% CI) | Interrupted (mean (s.d.)) | Active (mean (s.d.)) | Mean difference (95% CI) | Interrupted (mean (s.d.)) | Active (mean (s.d.)) | Mean difference (95% CI) | |

| Adverse events1 | 1.0 (1.1) | 2.1 (2.9) | -1.1 (-2.0 to 0.5) | 2.92 (3.7) | 2.12 (2.8) | 0.82 (-0.5 to 1.0)2 | 5.4 (3.4) | 1.4 (2.3) | 4.0 (2.5 to 5.0)*** |

| HRSD-21 score | 0.7 (4.3) | 1.2 (5.2) | -0.5 (-2.4 to 1.5) | 3.7 (5.8) | 1.5 (5.4) | 2.2 (-0.6 to 4.9) | 6.1 (6.4) | 0.8 (5.0) | 5.7 (2.4 to 7.8)*** |

| SAI score | 1.1 (9.7) | 1.7 (10.3) | -0.6 (-4.7 to 3.9) | 10.92 (19.0) | -0.12 (7.7) | 11.02 (-3.6 to 22.1)2 | 12.9 (15.9) | 1.4 (12.9) | 11.5 (4.9 to 16.5)*** |

| Self-assessment scores1 | |||||||||

| Work impairment | 0.4 (0.9) | 0.3 (0.9) | 0.1 (-0.3 to 0.4) | 0.7 (1.0) | 0.2 (0.8) | 0.5 (-0.0 to 1.0)† | 0.8 (1.0) | 0.0 (0.8) | 0.8 (0.3 to 1.1)** |

| Work missed | 0.2 (0.6) | 0.1 (0.6) | 0.1 (-0.2 to 0.3) | 0.2 (0.8) | 0.1 (0.5) | 0.1 (-0.3 to 0.5) | 0.4 (1.1) | 0.0 (1.0) | 0.4 (-0.1 to 0.8)† |

| Relationships | 0.3 (0.8) | 0.1 (0.7) | 0.2 (-0.2 to 0.5) | 0.2 (0.8) | 0.0 (0.9) | 0.2 (-0.2 to 0.5) | 0.7 (1.2) | 0.0 (0.9) | 0.7 (0.2 to 1.0)** |

| Social activities | 0.1 (0.6) | 0.2 (0.8) | -0.1 (-0.4 to 0.2) | 0.3 (1.0) | 0.2 (0.8) | 0.1 (-0.4 to 0.5) | 0.6 (1.1) | 0.1 (0.9) | 0.5 (0.1 to 0.9)* |

| Overall function | 0.3 (1.0) | 0.4 (0.9) | -0.1 (-0.3 to 0.3) | 0.6 (1.0) | 0.1 (0.9) | 0.5 (0.1 to 0.9)* | 1.0 (1.1) | 0.0 (0.9) | 1.0 (0.5 to 1.3)*** |

Among patients treated with sertraline there was an increase in the number spontaneously reporting dizziness during placebo interruption (placebo substitution 35.3%, active treatment 5.9%; P=0.007). Among patients treated with fluoxetine there was no statistically significant increase in spontaneous reports of any symptom during placebo substitution. At the end of the placebo substitution period, patients taking paroxetine, but not those taking fluoxetine or setraline, demonstrated statistically significant increases in HRSD-21 and SAI scores compared with the continued drug period (Table 2). There was no significant relationship between either dose or time on drug and new symptoms.

Functional impairment

Patients treated with paroxetine reported statistically significant deterioration in functioning at work, relationships, social activities and overall functioning, while patients treated with sertraline reported deterioration in overall functioning, and patients treated with fluoxetine reported no change in any area of functioning following placebo substitution (Table 2).

Vital signs

Patients treated with paroxetine experienced a statistically significant increase in standing heart rate and orthostatic change in heart rate (beats per minute) during placebo substitution relative to active medication (mean standing heart rate: active medication 78.7 (s.d.=12.2), placebo substitution 82.3 (s.d.=15.9), P=0.37; mean orthostatic change in heart rate: active medication 8.5 (s.d.=8.8), placebo substitution 12.5 (s.d.=13.1, P=0.020). There were no statistically significant changes in either measure among patients treated with sertraline or fluoxetine, and supine and standing blood pressure were similar for all groups during both conditions.

Plasma concentrations

Mean plasma drug concentrations (ng/ml) during active treatment and following placebo substitution, respectively, were as follows. Fluoxetine/norfluoxetine: active 264.6 (s.d.=160.3), placebo substitution 197.7 (s.d.=132.5), mean percentage reduction 29.7% (s.d.=15.8%); sertraline/desmethylsertraline: active 87.7 (s.d.=63.0), placebo substitution 26.0 (s.d.=33.0), mean percentage reduction 73.5% (s.d.=11.7%); paroxetine: active 46.7 (s.d.=33.4), placebo substitution 6.9 (s.d.=11.8), mean percentage reduction 86.7% (s.d.=12.9%). Percentage reduction in plasma concentrations across drug groups was statistically significantly correlated with new adverse events (r=0.56, P<0.01); however, within individual drug groups, correlations between new events and percentage reduction in concentration were not significant (fluoxetine r=0.0, P=0.98; sertraline r=0.19, P=0.30; paroxetine r=0.27, P=0.13). Neither absolute drug concentration in the steady state nor absolute change in concentration after interruption correlated with emergence of new symptoms following treatment interruption for any group.

DISCUSSION

Among patients whose depressive symptoms had responded to treatment and remained stable for at least four months, substitution of placebo for paroxetine was associated with new symptoms as early as after the second missed dose. These symptoms increased in severity and number throughout the five-day interruption period and were associated with a reduction in patient-assessed occupational and social functioning, as well as an increase in psychological symptoms. Patients treated with sertraline did not report an increase in the overall number of symptoms on the solicited adverse event scale during placebo interruption, but did experience increases in the severity of three out of 17 individual symptoms, accompanied by increases in spontaneous reports of dizziness and overall functional impairment. Patients treated with fluoxetine experienced no statistically significant increases in symptoms, symptom severity or functional impairment.

These data are consistent with reports from controlled clinical studies (Reference Rosenbaum, Fava and HoogRosenbaum et al, 1998) and epidemiological data (Reference Price, Waller and WoodPrice et al, 1996) suggesting that abrupt interruption of SSRI treatment is associated with the emergence of physical and psychological symptoms in a manner that suggests a relationship to drug plasma half-life. Our study differs from previous interruption studies in assessing the time course of symptom onset, symptom severity and the association of symptoms with functional impairment as well as changes in plasma drug concentrations.

Limitations

Several factors limit the interpretation of these data. Although the groups were well matched for baseline characteristics, patients were not randomised to treatment groups, and selection bias or expectations about the treatment groups could have influenced the results. This is unlikely to have been a significant factor, however, since the comparison periods were double-blind and order-randomised, and any effects due to patient or clinician expectations should have been observed during both periods. Also, a study in which patients were prospectively randomised to different treatments demonstrated results consistent with those observed here (Reference Fava, Rosenbaum and HoogFava et al, 1998).

Another limitation relates to the comparability of doses of the individual agents and to how these doses affected outcomes. The manufacturers' recommended doses were empirically derived from efficacy studies conducted separately for each drug, and could theoretically have differing biological activity at relevant loci. However, the drugs have similar preclinical serotonin (5-HT) profiles, the mean dose for each drug was modestly above the initial recommended starting dose and within its reported effective antidepressant range, and the doses reflect usual clinical practice, suggesting that they are comparable. Furthermore, the paroxetine mean dose was somewhat closer to the initial recommended starting dose than either the fluoxetine or sertraline dose, and any bias would be expected to be in the direction of symptom reduction for patients treated with paroxetine relative to the other treatment groups. Hence, it seems unlikely that the observed results are an artefact of dosing differences among the drugs.

Finally, crossover designs can be vulnerable to carryover effects. However, tests for carryover suggest that it was not a problem for most variables analysed. The few variables that reached statistical significance (P<0.1) were re-analysed using only patients from the first period, and the results were unchanged.

Perhaps the most important limitation of this study is the restriction of treatment interruptions to five days. It is possible that longer periods could be associated with the onset of symptoms among patients treated with fluoxetine or worsened symptoms among any of the treatment groups. We note, however, that interruptions of up to eight days demonstrate patterns of effects consistent with those reported here (Reference Rosenbaum, Fava and HoogRosenbaum et al, 1998), and it seems unlikely that clinically relevant interruptions (as opposed to discontinuation) would last significantly longer than this. With respect to discontinuation of medication, longer periods may be more relevant to fluoxetine. In one trial (Reference Zajecka, Fawcett and AmsterdamZajecka et al, 1998) patients with major depression successfully treated with fluoxetine for 12-14 weeks and then abruptly switched to placebo reported a modest but statistically significant increase in dizziness (which was reported by approximately 10% of discontinuing patients over the following six weeks compared with approximately 4% of those continued on fluoxetine), without evidence of other signs and symptoms. These figures probably represent low estimates of the incidence of this symptom, since assessments were obtained by spontaneous rather than solicited reports.

Clinical relevance

A previous report (Reference Rosenbaum, Fava and HoogRosenbaum et al, 1998) suggests that SSRI-related discontinuation syndromes, although uncomfortable, are self-limited and generally resolve within 1-2 weeks; our results are consistent with these findings. In this context, the most important clinical risks seem more likely to be related to appropriate recognition and management than to the morbidity of the symptoms as such. Discontinuation symptoms can include prominent psychological manifestations, and patients who experience discontinuation symptoms after stopping medication could be misdiagnosed as having relapsed, and as a result have therapy reinstituted prematurely. Similarly, a body of data suggests that many patients have gaps in medication compliance or stop medication spontaneously, and our results suggest that some patients, particularly those taking paroxetine, will develop interruption-related symptoms that may be viewed as breakthrough depressive symptoms or some other condition (e.g. influenza). The degree to which such problems actually result in inappropriate or unnecessary treatment, however, is not known.

Also of clinical interest is time of exposure. We did not find an increased risk related to longer exposures. This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that a minimum period is required to establish new physiological conditions related to drug administration, but that drug-related changes are stable once in place.

Finally, an important clinical question is the degree to which new symptoms following treatment interruption represent a specific, drug-related phenomenon rather than depressive relapse. The characteristic presence and predominance following interruption of specific physical symptoms including dizziness and nausea are not typical of depression, and suggest instead an acute disruption of a drug-induced homoeostasis. Our findings are also consistent with effects observed with other drugs, such as rebound hypertension following discontinuation of antihypertensives, again suggesting a specific interruption effect. None the less, because the diagnoses of both discontinuation syndromes and depression are based on descriptive findings rather than markers of underlying pathophysiological processes, we cannot definitively rule out the possibility that some or all of the observed increases in symptoms are related to relapse of underlying illness.

Potential mechanisms underlying symptom production

The mechanisms which underlie discontinuation phenomena are incompletely understood, but symptom production appears to be most closely related to the rate at which internal disruptions occur. Although fluoxetine, sertraline and paroxetine have some differences in their in vitro receptor profiles (Richelson, Reference Richelson1996, Reference Richelson1998), the most apparent difference is in their pharmacokinetic half-lives, and the resulting rate of clearance of parent drug and active metabolites from relevant pharmacodynamic targets. We observed a pattern of symptom emergence and increased severity which parallels the plasma half-lives of the drugs, strongly suggesting that half-life is indeed the most important factor. This finding is consistent with data from other drug classes, such as antihypertensives, implicating shorter plasma half-life in producing these phenomena (Reference Rickels, Fox and GreenblattRickels et al, 1988; Reference Schweizer, Rickels and CaseSchweizer et al, 1990; Reference Noyes, Garvey and CookNoyes et al, 1991).

The nature of the symptoms observed could potentially be related to a primary effect on serotonin production, release or receptors, to secondary effects on systems modulated by serotonergic pathways, or some combination of these. Although secondary effects may be important, the pattern of individual symptom frequency observed here supports a primary aetiological role for alterations in serotonin homoeostasis. Consistent with previous studies, dizziness was the most common symptom for both paroxetine- and sertraline-treated patients (reported spontaneously in approximately a third of both groups). Dizziness is commonly observed in the context of 5-HT1A receptor stimulation, and its high incidence during placebo substitution is consistent with a primary effect on serotonergic neurotransmission (Reference Grof, Joffe and KennedyGrof et al, 1993). Another common symptom was nausea, thought to be mediated by the 5-HT3 receptor, and serotonin is believed to have important roles in modulating psychological symptoms observed in this study, such as nervousness and agitation (Reference Kilpatrick, Bunce and TyersKilpatrick et al, 1990; Reference RichelsonRichelson, 1998). It is likely, however, that other factors also influence symptoms. The changes in heart rate observed during treatment interruption in the paroxetine group, for example, could represent alterations in noradrenergic-sympathetic nervous system function.

Relationships to plasma drug concentrations

Neither doses nor absolute plasma drug levels correlated with symptoms associated with treatment interruption for any group. Plasma concentrations achieved at a given dose of an SSRI vary widely between individuals and do not correlate with efficacy (Reference Nielsen, Morsing and PetersenNielsen et al, 1991; Reference Amsterdam, Fawcett and QuitkinAmsterdam et al, 1997), and plasma concentrations may not accurately reflect brain exposure. In this regard, a recent report on brain paroxetine and fluoxetine concentrations measured by magnetic resonance spectroscopy before and after treatment interruption suggests a relationship between higher steady-state brain concentrations of paroxetine and new symptoms experienced when treatment is interrupted (details available from the first author upon request). However, it is also likely that the lack of correlation between symptoms and plasma concentrations reflects individual differences in concentration-effect relationships at the receptor level, and that the lack of a dose-symptom relationship parallels the lack of a therapeutic dose-response relationship.

By contrast, there was a statistically significant relationship across all drug groups between percentage reduction in plasma concentration and the appearance of new symptoms. Within each individual drug group this relationship was not statistically significant (although correlations appeared to increase from fluoxetine to sertraline to paroxetine in the predicted direction). This is probably because in the group with the most symptoms, namely those treated with paroxetine, virtually all drug had been eliminated in most patients at the time of measurement, because differences in half-life across drugs are much greater and more important than those among individuals taking any single drug, and because inter-individual differences in plasma concentration reflect not only half-life but also absorption, protein binding and distribution. These findings, while not providing definitive proof of a role for half-life in the development of new symptoms after treatment interruption, are consistent with the hypothesis that it is the major risk factor.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ New physical and psychological symptoms relating to treatment interruption or discontinuation can emerge within two days of stopping or interrupting treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs); the risk is highest for paroxetine, lower for sertraline and lowest for fluoxetine.

-

▪ The differential diagnosis of either early relapse after ending treatment or breakthrough symptoms during ongoing treatment with SSRIs should include the possibility that symptoms are related to missed doses or discontinuation rather than return of underlying depressive illness.

-

▪ Dizziness is the most common symptom resulting from interruption or discontinuation. Other common symptoms include unusual dreams, nausea and fatigue or irritability.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ Treatment interruptions were limited to five days; longer interruptions could result in different outcomes.

-

▪ Patients were not randomised to therapy groups, and differences among groups could potentially have accounted for some of the observed results.

-

▪ Research conditions differ from clinical practice, and the degree to which the findings significantly affect patients under non-research conditions is uncertain.

APPENDIX

Items included in the patient-rated adverse events scale

-

1. Dizziness

-

2. Nausea

-

3. Unusual dreams

-

4. Tiredness or fatigue

-

5. Irritability

-

6. Unstable or rapidly changing mood

-

7. Nervousness

-

8. Headache

-

9. Difficulty concentrating

-

10. Muscle aches

-

11. Feeling tense

-

12. Chills

-

13. Crying easily

-

14. Trouble sleeping

-

15. Sweating

-

16. Feeling agitated

-

17. Diarrhoea or loose stools

Self-assessment of occupational and social functioning

-

1. During the past four days, have you had difficulty functioning at work, or had to miss time from work? If you are not working outside of the home, please consider your ability to perform your usual daily routines?

-

1. No difficulties

-

2. Minimal difficulties (notice some problems, but still able to perform adequately)

-

3. Moderate difficulty (definite decrease in performance)

-

4. Severe difficulty (had to miss time from work or unable to perform usual daily routines)

-

-

2. How much work (if any) did you miss in the past four days?

-

1. No work missed

-

2. Less than one day

-

3. 1-2 days

-

4. More than two days

-

-

3. During the past four days, have you noticed any problems in your relationships with family and friends?

-

1. No problems

-

2. Mild problems (some irritability or tension with others)

-

3. Moderate problems (marked irritability or tension and/or actual arguments and conflict)

-

4. Severe problems (have not wanted or felt able to be around others)

-

-

4. During the past four days, have you felt uncomfortable in social settings or restricted your usual social activities?

-

1. No discomfort

-

2. Somewhat uncomfortable but have not restricted social activities

-

3. Some restriction in social activities (avoiding some of usual activities)

-

4. Severe restriction in social activities (avoiding most or all of usual social activities)

-

-

5. During the past four days, how would you describe your overall functioning?

-

1. Excellent

-

2. Good

-

3. Fair

-

4. Poor

-

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.