“Like father, like son.” In March 1968, Stag ran a short yet tragic piece on a World War II and Korea veteran whose son had a choice between college or Vietnam. The nineteen-year-old “naturally” opted for the Marine Corps and was assigned to a combat unit in Quang Tri, “right in the heart of the action.” His father worried for his son’s safety, though, and after finding a loophole in military regulations, pulled some strings, reenlisted, and headed to Vietnam, joining the same outfit as his boy. “He made it up to the battalion command post,” Stag reported, “just as remnants of a patrol were straggling in. Cornering one of the surviving Marines, the uneasy father asked if the soldier knew his son. ‘Oh, yeah,’ came the weary reply. ‘He got killed.’”1

Published as the 1968 Tet offensive was still raging across much of South Vietnam and domestic support for the war appeared to be fracturing, Stag’s terse homage left a clear message. This patriotic family was serving its nation, even at great personal cost. The article ended by noting how the father flew back home with his son’s body to attend the funeral, but was “still eligible to return to his unit on the line in the Far East.”

Pulp stories like this highlighted how gendered codes of conduct helped reinforce child rearing during the Cold War era. Fathers raised their sons to value service in uniform. They transmitted the valorization of manhood and encouraged behavior that reflected these ideals. In the process, boys hardly questioned the manner in which their own definitions of masculinity were being militarized.2 To one Vietnam veteran, his dad “was a hero. As kids growing up in the fifties, we used to play army all the time, and we’d talk about what our dads had done.” Another, Bill Ehrhart, similarly recalled sneaking into the bedroom of a friend’s father and stealing a look at his Silver Star. “When we finally screwed up enough courage to ask him how he’d earned it,” Ehrhart remembered, “his modestly vague response fired our ten-year-old imaginations to act out the most daring and heroic deeds.”3

In many ways, men’s adventure magazines helped young boys emulate their World War II and Korean War fathers. However, the pulps also offered appealing narratives for the veterans themselves. Within these magazines, men could find multiple versions of masculine citizen-soldiers – just and moral warriors, youthful combatants, heroic protectors, and sexual conquerors.4 Here was an escape from overbearing wives and domineering bosses, perhaps even an antidote for those veterans who felt emasculated by their post-traumatic stress and were reluctant to share their pain. In pulp war stories, the heroes never suffered such frustrations. They shone in a wartime environment and passed the test of manhood with flying colors. As the nation’s protectors, they made the difference between survival and extinction. In short, the macho pulps reinforced the overarching narrative of war as a masculine sphere of influence.5

This narrative construction seemed particularly important given the transition from the unconditional victory of World War II to the indecisiveness of Cold War era conflict. With the termination of hostilities on the Korean peninsula in 1953, Americans confronted the possibility there might be limits to US military power overseas. How was it possible, many wondered, that more than 33,000 American GIs had died in combat for a negotiated settlement that left the communist enemy still standing? If men were expected to serve and protect the nation, did such an unsatisfying conclusion portend a coming crisis, not only in American masculinity but in national security as well? A more positive view of battlefield exploits might ameliorate such worries. Men’s magazines thus carved out space for accounts remembering and celebrating a more “heroic” period of war, tales no doubt desired by their readers, young and old alike.6

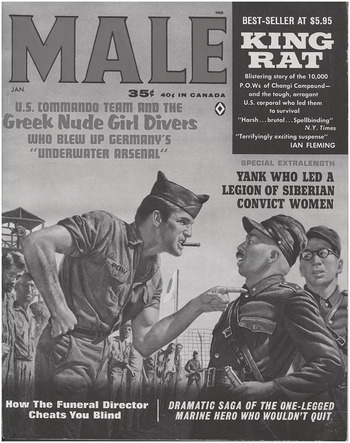

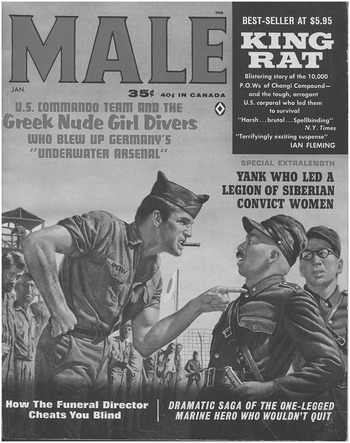

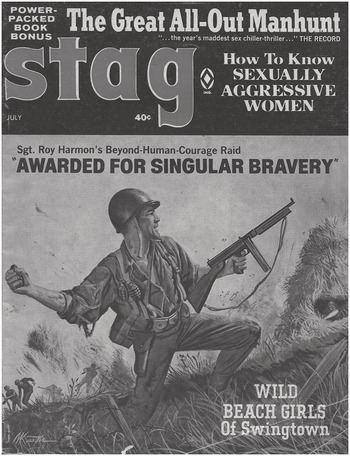

Indeed, the macho pulps courted two audiences. They sold themselves as both a friendly genre for veterans and a way for curious young teens to get a glimpse of what war might be like. Men’s magazines tended to humanize American GIs, showing unvarnished respect for their service and sacrifices. One Stag author, for example, denounced what he saw as the “unfair or unrealistic treatment” of men in uniform. “If we want the security provided by a dedicated military, then it’s time we level with our GIs and started giving them the fair shake they deserve.” Just like popular 1950s television series such as Crusade in Europe and Victory at Sea, the pulps also presented virtuous Americans clashing dramatically with savage Nazis and fascists. “Singular bravery” could be found in the pages of almost any adventure mag. Along the way, military service became the embodiment of a masculine ethos.7

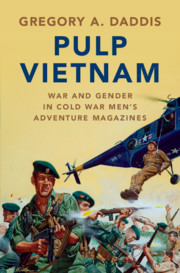

Fig. 2.1 Stag, July 1966

Just as importantly, the pulps also seduced younger readers with an opportunity to learn about the man-making experience of combat. These would-be soldiers, already imagining fighting in their own wars, proved a receptive audience. War permeated American youth culture in the 1950s and early 1960s. Boys built models of Spitfire and Messerschmitt airplanes while devouring books like The Desert Fox and Thirty Seconds over Tokyo. In New Jersey, Bruce Springsteen remembered passing afternoons as “Hannibal crossing the Alps” or “GIs locked in vicious mountain combat.”8 A recently graduated lieutenant from the Virginia Military Institute wrote an approving letter to Saga about its story “The Day the Kids Went to War,” a rousing tale of the 1864 Civil War battle of New Market. Most likely, more than a few teens attentively read through Climax’s “Baptism of Fire.” The magazine wanted to know what it felt like “the first time under fire,” so it dispatched photographer Bob Schwalberg to Fort Dix, New Jersey so he could go through the infiltration course for GI trainees. At story’s end, with the reader in tow, Schwalberg proclaims, “You’re a ‘veteran,’ now. You’ve had your baptism of fire and you’re ready for the Real Thing – you hope!”9

Yet for veterans to wax nostalgic over their wartime experiences and for young boys to remain hopeful war would make them into men, the pulps had to accentuate the positive aspects of American GIs in battle. Myths had to be constructed and framed in such a way that the needs of Cold War society could be fulfilled by a “good war” narrative. In this way, as pulp writer Mario Puzo maintained, World War II was a “gold mine.” Properly fabricated, the memory of the Second World War might guide new recruits as they deployed to Southeast Asia in search of martial glory. At very least, pulps like Man’s Epic could showcase the heroism of those courageous GIs who “smashed open the door to France” in the summer of 1944. Even when it was becoming clear the war in Vietnam might be mired in a stalemate, men’s adventure magazines still emphasized the very best of Americans at war.10

Veterans Remember

Much of what American society read about combat in World War II was a sanitized version of reality. Advertisements, film, and even letters home rarely shared the dark side of war. Indeed, watching war films could lead some viewers to believe ground combat looked something akin to a “choreographed football scrimmage.” Despite this often rosy outlook, it would be wrong to assume that all Cold War teens regarded military service as a highly prestigious profession. A 1955 Gallup poll suggested that many teenagers thought enlisted soldiers remained in uniform because they were “either unable or unwilling to make a civilian living.” Two years later, a Harper’s Magazine correspondent found that armed forces recruiting ads targeted “a young but relatively sophisticated audience which feels little romantic enchantment about wars or about the men who fight them.” If Americans increasingly were seeing World War II as a “good war,” clearly not all were convinced.11

Men’s adventure magazines, however, carved out a pop culture space where the “good war” narrative flourished. The pulps feted GIs and their individual heroism, for these citizen-soldiers exemplified the best of American grit and spirit. Within the magazines’ covers, war-related storylines were neither complex nor ambiguous. Good triumphed over evil. Soldiers proved themselves as men. Moreover, because so many veterans remained hesitant to share their personal stories with family and friends, romanticized interpretations of the Second World War more easily took hold in 1950s society. As such, the lack of honest conversation from World War II and Korea veterans may have indirectly legitimized the pulps. Without dissenting voices to contest or provide nuance to the prominent narrative, adventure magazines could lay claim that they were offering the “real” or “hidden” history of America’s greatest war.12

Of course, veterans themselves contributed to the pulps. Stag’s editorial director, Noah Sarlat, was a World War II vet. So too was Walter Kaylin, one of the most prolific writers of the genre. Kaylin, a graduate of William and Mary College, served as a radioman in the Philippines with the Army Signal Corps and no doubt relied on his experiences when crafting pulp sagas. Like so many of his peers, he also could be prone to hyperbole. In his 1964 account of the Burma campaign, published in Male, Kaylin lauded the “towering heroes” who led a handful of allied troops to become “the savage pliers that pulled the Japanese army’s teeth out of Asia’s throat and turned the Burma Road into a four-lane highway straight to Tokyo.”13

As a former radioman, though, was Kaylin living vicariously through the tales of men braver than he? Communication equipment operators never rated as lead protagonists in adventure tales. Pulp illustrator Norman Saunders believed these magazines were geared to the majority of men who had served in the war, but not in actual combat. As his son revealed, “He felt that men who saw action never wanted to think about it again, while most servicemen who never reached a front line were doomed to a life of wondering about their manhood in the face of battle.” Surely many teens also speculated about their battle worthiness. In fact, Kaylin recalled that his primary audience was young men “who wanted stories with action, violence and ridiculous sex.”14

While boredom proved a common experience for many World War II veterans, those who did see combat often repressed their struggles to cope with the horrors of war. A late 1945 study of those soldiers still in the army found that most had felt the “experience had done them more harm than good.” Over forty percent of those surveyed said they were more nervous, high-strung, and tense after their service. Few of these veterans, however, shared their pain. One Vietnam vet noted how his father never talked much about World War II “except for the usual glorious things, about service to the country and becoming a man.” When the son returned home from Vietnam, only then did his dad start talking about “the killing and the death.” Another veteran of the fighting in Europe admitted that his children did “not know all the things that happened in the World War. I prefer that they don’t.” Additionally, Korea vets found their war had been little more than a distraction to those back home, likely adding further impediments to recounting any horrors they had seen.15

The pulps, though, served as a unique venue for veterans to unburden themselves by offering a safe space where wartime stories nearly always left an inspiring message. In the process, the magazines helped to democratize war. Everyone had potential to tell their story, even the lowliest private. Writing could become a form of catharsis, especially for those unwilling to reveal the ugliness of war with their own families.16

One young paratrooper recounted the perils of a night jump over the island of Sicily in 1943, the whole world “screaming” in his ears as he exited the transport plane. Kaylin wrote on the 1942 invasion of Guadalcanal and its subsequent defense by marines who bravely withstood an “avalanche of booming destruction” that had burst down on them. In its February 1956 issue, Battle Cry ran a story on invasion planning by Major Howard L. Oleck. Oleck detailed the logistical requirements of assaulting an island like Iwo Jima or Guam, the air support needed to cover the landings, and the role of the intelligence staff in estimating enemy troop dispositions. Yet the author knew success depended on more than just moving pins on a war map – “when the men hit the beaches and the first shot is fired, you can forget about the plans and the schemes. Now it is up to the GIs and the Marines who will try to carry it out. And they always do.”17

Such a tribute hinted at another role the macho pulps played by publishing war stories. They allowed senior officers to extol the bravery and heroism of those men who fought below them in critical battles. (Might they share in the subordinates’ gallantry?) Former Marine Corps commandant Lemuel C. Sheperd, Jr. opened his account of the fighting on Okinawa with a plucky corporal who cracked jokes “in the face of withering fire.” Writing in 1959, Sheperd dismissed atomic age “push-button-war” advocates and recounted what he saw as the “good old days” of World War II. “When the chips were down man met man in mortal combat.”18

Heroic and congratulatory accounts alluded to something more private – war was an experience to look back upon fondly, even for veterans who spent World War II wishing it to be over so they could return home. Such “sentimental militarism” found a welcome place in the adventure mags. Myths could be constructed and recycled wherein patriotic citizen-soldiers sacrificed for the nation, proved their manhood, and then returned to raise boys capable of following in their footsteps. One veteran wrote to Battlefield that after reading a story on the 3rd Armored Division in Europe, the “memories came flooding back” of the “great bunch of fighting men” with whom the author had served. “The fierce determination of the tankers as they led the charge into Germany will always be remembered by me with pride,” he shared.19

Of course, such sentiments rested uneasily alongside the 1945 survey data suggesting that “more men reported undesirable than desirable changes” immediately after being discharged from the army. Might it be that over time veterans were privileging wartime myths and fantasies over their own experiences? In retrospect, how many men agreed with their comrades who professed that their wartime service was the time they felt the most “manly” or “rugged,” “the way a man ought to feel”?20 After deploying overseas and fighting in a global war, how many returned to suburbia and found their civilian lives monotonous, if not somehow inconsequential? To these men, it seems likely that the macho pulps may have resonated more deeply. There they could find electrifying stories of rugged World War II bomber pilots crash-landing behind enemy lines, and then joining the French Resistance to sabotage a key bridge over which the Nazis were planning to send reinforcements to pinch off the D-Day beachheads in Normandy. In the pulps, men mattered.21

If the magazines inspired a sense of nostalgia while also allowing men to reaffirm their masculinity, they equally gave readers a chance to engage with pulp writers and editors. In an important way, letter sections allowed veterans to participate in a larger, albeit sometimes mundane, dialogue about war. Readers certainly were not shy. One “critical paratrooper” cried foul about a story in which a ripcord got tangled up, while Real was taken to task for getting the details of war medals wrong.22

Besides offering technical critiques – Mario Puzo recalled getting scolded for “incorrectly identifying a tank tread or rifle designation” – veterans responded to pulp stories with their own anecdotal accounts. After reading “First GIs on Omaha Beach,” as an example, one shared how his unit was ambushed by Germans near the town of Longville, France. “I am not much of a writer or story teller,” he admitted; “the ambush was only a matter of three minutes, but it would take three hours to tell. I will never forget it as long as I live.”23

This engagement with the pulps created, in David Earle’s words, a “symbiotic supply-and-demand relationship between reader and magazine.” It was a tradition that carried on into the 1960s. Soldiers wrote in to ask if they could meet a certain cheesecake girl, one sharing that Bluebook’s photos of model Diane Dexter were tacked to the barracks wall, making “this army grunt stuff easier to take.” A marine corporal in South Vietnam shared how he was “out here fighting ‘Charlie’ for eight months without the sight of a decent chick.” Along the same sex-hungry lines, an airman with the 18th Tactical Fighter Wing in Okinawa disappointedly wrote to Real’s editors: “I’d try your J.B. (James Bond) approach to women, but over here, for some reason, they don’t talk like you say. So solly, have to wait’til I get home.”24

While the pulps most certainly contributed to this racialized sexism – clearly a product of the Cold War era – many letters from GIs in Vietnam attended to more banal topics. One reader complained about the South Vietnamese censors, while a lieutenant stationed in Saigon cleared up a few missteps made by Saga in a recent story about comic books. Additionally, a marine stationed in Vietnam blasted a fellow letter writer who argued that older men in their late thirties or early forties were just as capable as the young men serving in Southeast Asia. “I have news for him,” the marine declared. “It has been proved that the young can withstand more hardships than the old … We are a new breed of fighting man, the finest the world has ever seen.”25

Editors surely presented veterans’ letters in such a way as to make the most impact on their readership. Yet they also took it upon themselves to advocate for vets and help educate them on their rights. True War, for example, advised readers in 1957 to pressure their congressional representatives on what it saw as a “serious GI housing loan bottleneck.” That same year, Adventure responded to a Camp Pendleton marine asking for advice on using the GI Bill, even offering to send the young man a booklet on careers in forestry.26 In the same vein, Real War included a department called “The Service Bureau,” which aimed to answer questions on government benefits and veterans’ rights. Topics ranged from civil service careers to discharge paperwork to working through the VA system. In Battle Cry, old soldiers could turn to the “Whatever Happened to—?” section in hopes of reconnecting with lost buddies. Meanwhile, other magazines, like Stag, regularly ran articles warning servicemen of corrupt civilian businesses looking to take advantage of the gullible GI.27

Of course, it did not hurt that vets could rely upon advocates outside their formal ranks who helped tell their stories. Men’s adventure magazines regularly showcased nationally renowned authors and historians who wrote sympathetic treatments of the American wartime experience. In many ways, the values of GIs in battle – tenaciousness, courage, rugged individualism – came to symbolize an idealized version of larger American values. In commemorating these GIs, the pulps featured pieces from famed novelists like Norman Mailer and respected military historians such as Richard Tregaskis and Robert Leckie. In the November 1963 issue of Man’s Illustrated, Leckie combined stirring prose with dramatic photos of the US Marines’ “savage attack” on the island of Saipan in World War II. The brutal fighting left little room for quarter. As the article noted, the “last ditch effort by [the] Japs, who preferred to die rather than surrender, left Marines no choice but to fight to the bitter end.” And, because this was a men’s mag, Leckie’s story immediately was followed by a photo spread of a nude Las Vegas showgirl tantalizingly swimming in a pool.28

In addition to offering memories from “ordinary” veterans, the magazines also excerpted storylines from celebrated authors like war correspondent Ernie Pyle and offered a “book-length adventure” pulling from James Clavell’s King Rat. Retired brigadier general and military historian S.L.A. Marshall contributed several tributes, most notably on the twentieth anniversary of D-Day, where his oral histories focusing on the individual combatant brought readers down to the lowest levels of the tactical battlefield. If “God helps the bold,” as Marshall claimed, then the almighty could find no better candidates for assistance than those daring Americans assaulting the Normandy beachheads on 6 June 1944.29

Such narratives contained little subtlety lest readers miss the point. War was a contest between good and evil, and Americans always wore white hats. This plot point certainly helped set the foundation for the “greatest generation” myth, advanced by such nationalistic historians as Stephen Ambrose, who argued that democracies produced better soldiers than totalitarian regimes. As Ambrose claimed in his popular work Band of Brothers, the United States won in World War II because “Americans established a moral superiority over the Germans.” The less complicated the narrative, the more likely the war could be used, in Michael Dolski’s words, as an “instructional tool to guide younger generations.”30 Thus, young Fury readers could aspire to be like Jimmy Doolittle, the legendary pilot who led the first air raid over Japan after Pearl Harbor. “The United States was fighting for its life in the greatest war in all history,” the Fury article declared. “His country needed him, and he was still to give her all the brilliant leadership and fighting fury he could command.”31

The stark comparisons between American democratic values and Japanese militarism or German Nazism likely help explain why infiltration into or escape from Nazi prison camps became such a popular entry in the macho pulps. Yet the traditional captivity narrative also allowed men’s magazines to feature the best of military masculinity. In these stories, men may have been captured, but they hardly were submissive “captives.” In fact, the drama built from their ability to resist their captors, to mine the best qualities of human nature for survival, and, ultimately, to escape back to freedom. Along the way, in the pulps at least, bikinied women often entered the story so they could properly demonstrate their gratitude to the self-assured hero.32

World War II escape-from-captivity narratives proved an adventure mainstay in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Air Force prisoners of war, as one example, were able to flee from “escape-proof stalags,” while in its very first issue War showcased “Breakout King” Jerry Sage, a “strapping, blond giant” and innovative US Army officer who apparently came to the attention of Hitler himself. “They chained him to walls, threw him into ‘steel coffin’ cells, buried him in underground ‘mole holes’ – but always this indomitable Houdini of a Yank POW found a way out.” Stag ran a similar piece on pilot Larry Haber, dubbed “Capt. ‘Bustout.’”33

Not to be outdone, Mario Puzo penned a “complete book bonus” for Male in early 1965. The story centered on Bax Durkin, a “stubborn stallion-muscled ex-football player” leading a band of allies out of war-torn Singapore in 1942. In the yarn, Durkin is an American architect who, after the Japanese invade, voluntarily joins an Australian infantry battalion and is in disbelief that “these puny Japs were beating the hell out of the armies opposing them.” After helping four other civilians escape imprisonment, it is Durkin who leads the party – including, of course, two attractive women – pushing them “mercilessly” through the jungle. (Apparently American architects are far better navigators than any Australian infantryman.) On the third night, Durkin wrestles with a bout of food poisoning but is “cured” by nurse Kay Medford, who once was told that “sexual release can act as a sedative in place of drugs.” Back on his feet the next morning, our hero guides the ragtag group on an adventure-packed trek for another 1,000 miles before ultimately leading them “home, safe again in the Free World.”34

Rambo himself could not have performed better. Indeed, the pulps arguably had established a prototype of hypermasculinity for future action heroes to emulate long before Rambo ever first set foot in Vietnam.

Cold War “Rambo”

War stories tend to focus attention on elite units or tales of personal heroism rather than on the average soldier who often suffers most, and the postwar pulps took a keen interest in army rangers, commandos, and airborne paratroopers, who were indisputable warriors. These men stood apart, winning their battles – and their manhood – on an individual basis. In small-unit combat, men controlled their own destinies. They retained their distinctiveness on the mass industrial battlefield. Through acts of near-superhuman strength, they could right wrongs, as in True Action’s “The Ranger Raid to Save 512 Dying Yanks.” In a storyline comparable to Rambo: First Blood Part II, elite US Army soldiers, a “handful of the toughest, deadliest knife-fighters in the Sixth Ranger Battalion,” break into a Japanese prisoner camp to save survivors of the Bataan Death March. These saviors are “mean, tough, gutty daredevils, and … best of all, smart and disciplined.” Unsurprisingly, every prisoner makes it back alive. Readers thus could share in the triumph and courage of such an elite unit, making possible a sense of “collective glory” felt by all Americans.35

This focus on individual and small unit actions allowed pulp writers to rejuvenate those self-reliant pioneers who had carved out civilized spaces on the edge of the North American wilderness. Male, for instance, harkened back to the colonial era in its chronicle of Sergeant Alvin York, a “war-hating Tennessee backwoodsman” who fought in World War I and became the “deadliest Yank rifleman of all time.” The article described York as a “latter day descendant of the American frontier, a plain-talking, no-nonsense sharpshooter,” a “striking-looking man with a body hardened by years of physical labor, hunting and hiking, and a natural leader.” As the body count escalated, the Tennessean won praise from his commanders and became a national sensation. General John J. Pershing called York the “greatest civilian soldier of the war,” while Male linked his stunning war record to the “old-fashioned virtues of pride and patriotism.”36

Luckily for the nation, citizen-soldiers of the “greatest generation” were more than capable of following in York’s footsteps. A 1957 account in True War focused on the men of the 101st Airborne Division, a popular unit among pulp writers. Cut off and surrounded during the World War II Battle of the Bulge, determined paratroopers “held out against a total of 12 savage attacks” as the Germans continued “plastering the defenders with tons of shrieking high explosives.” Guy likewise highlighted the saga of “Slim” Jim Gavin, who had risen from private to major general and wartime commander of the famed 82nd Airborne Division. The magazine pointed out that Gavin had made more than 200 parachute jumps, a “rare kind of fighting man” who “took on the Nazis and ripped them apart.” That both York and Gavin came from humble origins implied that becoming a wartime legend might be in the grasp of any pulp reader.37

This focus on elite units also foreshadowed the near-cult status achieved by the US Army’s Special Forces in the early 1960s. The Green Berets, a favorite of President John F. Kennedy, not only fought along the Cold War frontiers, but also served as advisers and “bolsterers of democracy.” While regular army commanders looked warily upon their special-operations brethren, pop culture fawned over these heroic warriors who seemed equally capable in hand-to-hand combat and cultural sensitivities.38 A post-Vietnam War study comparing men in the Special Forces with war resisters even claimed a heightened sexuality among these elite soldiers. They first experienced sex at the average age of fifteen, far younger than civilian doves, and notched up a remarkable “28.5 contacts with prostitutes per man.” In yet another arena, young boys could find a distinct relationship between martial masculinity and sexual prowess.39

On rare occasions, antimilitarism would crop up to contest these heroic exploits of intrepid warriors. In its inaugural issue, Battle Cry ran a comedic piece titled “I Was a Filing Tiger,” an obvious play on Claire Chennault’s famed “Flying Tiger” volunteers of World War II. Written by a quartermaster corps clerk who dismissed frontline “glory-hounds,” the article noted that it was “pretty hard to dig up dames if you’re living in a fox hole or pup tent.” Away from the shooting, rear-echelon troops could take advantage of the supply system, and the black market, all while staying warm and well-fed. An accompanying photo shows a bespectacled, lean private sitting behind a typewriter as a curvaceous female secretary bends over him. Thanks to her low-cut blouse, he is able to stare directly at her breasts, the sidebar text blatantly sexist. “A GI can get shellshocked at a job like this,” the private declares, “did you ever see such artillery!” Turn the page, however, and battlefield bravery returns in a tale about the World War II fighting in New Guinea. Apparently, working deals to stay out of harm’s way had its limits. What young man would want to read a magazine called Coward anyway?40

Rather, men’s magazines churned out tales where heroism stood at the center of “adventure.” The “Filing Tiger” may have avoided derring-do, but the pulps situated him in stark comparison with men who displayed masculine qualities so desired by military leaders – physical fitness, mental and emotional strength, and an ability to perform as an individual or member of a hard-hitting team. Adventure mags frequently intensified these traits to near-superhuman levels. In “I Was a Commando Raider!” a World War II veteran recalled being a twenty-year-old US Army ranger charged with sneaking through enemy fortifications, locating a train-load of naval mines, and blowing them up before they could be emplaced in a strategic harbor. A similar entry from Valor magazine detailed the exploits of the men spearheading the 9th Armored Division as it raced toward the Remagen bridgehead in Germany’s Rhine province. The “men-in-battle” feature spotlighted a young lieutenant leading the bridge crossing and promised readers “a first-hand account of gallantry and valor toward which all armies strive but few attain.”41

Without question, the best way for men’s magazines to highlight singular acts of bravery was to run stories on recipients of the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest award for valor in combat. This they did regularly.42 Stag trumpeted the “beyond-human-courage” of Sergeant Roy Harmon who served in the 91st Infantry Division during the allied offensive in Italy. In tough fighting against German forces, Harmon’s unit became pinned down by enemy fire. Though wounded, the sergeant continued a one-man assault against three enemy positions, successfully destroying them before being riddled by German bullets.43

Though Harmon was awarded his Medal of Honor posthumously, one Korean War recipient lived through his own battlefield ordeal. Operating south of Seoul in early 1951, Captain Lewis L. Millett led his marine infantry company in what S.L.A. Marshall characterized as “the most complete bayonet charge since Cold Harbor in the Civil War.” In its first issue, War gushed over the “muscular New Englander” who made all the marines in his unit “cold steel conscious” by issuing them brand new bayonets. When Millett and his men confronted enemy troops in February, they were ready. Attacking a North Korean defensive position, Millett screamed with “wild defiance” as he slashed and jabbed his way forward. To War, there was “something primitive and personal in that gleaming pointed bayonet. There was something animal and lethal in the American officer’s ear-splitting shouts.” Of course, the Americans took their objective, “wrecking” the enemy. Just as importantly, though, Millett proved that he had not forgotten “old fashioned Dan’l Boone tactics.”44

The warriors highlighted in men’s adventure magazines also proved that Americans were the real heroes of World War II and, to a lesser extent, Korea. Harmon and his brother warriors helped lead the larger cultural shift that ultimately bequeathed the “greatest generation” narrative to a grateful nation. According to the now legendary tale, shared by Robert McDowell, these Americans transcended “motivations of self-interest” and pulled together to “do uncommon, extraordinary things.” In full agreement, one newspaper account declared that these “citizen heroes” – and occasional heroines – “put themselves on the line” and “saved the world.” They became symbols of all that was good in America, an example for future generations to follow in a world reengaged in a global struggle of good versus evil.45

This militarized glorification of masculinity served as an essential antidote to the presumed emasculating influences of Cold War America. Across the globe, tough men had survived the worst of war. Individual, virile warriors were in control of war’s chaos. Perhaps, then, their example could remedy the influence of smothering moms who apparently were raising a generation of “sissies.” The pulps’ conceptions of military masculinity might prod young ones into developing themselves physically for service to a nation at war. Clearly, their country needed them. According to Stag, by late 1968 more than “40,000 GIs were drafted into the armed forces over the last two years who were later found physically unfit.” The magazine, however, failed to mention that in World War II, senior military officials similarly worried about the physical condition of America’s youth. As one colonel serving in the War Department reported, “Many young men are entering the army today totally unprepared for military life.”46

Not so in men’s adventure magazines. There, young American men were hardy, resilient, and physically powerful. In Stag’s account of the 1942 Battle of Midway, the heroic Ensign George H. Gay is described as a “lean, hard-muscled flyer.” Across the globe, fighting in Italy, Maurice Britt’s heroism earned him the Bronze Star, the Silver Star, the Distinguished Service Cross, and the Medal of Honor. Men detailed this “One-Man Army” who had played football at the University of Arkansas as having “tremendous speed,” “remarkable stamina,” and “massive power.”47 Likewise, the adventure magazine highlighted US Navy Lieutenant Hugh Barr Miller, a “shrapnel-torn phantom who wouldn’t die.” Operating in the British Solomon Islands, Miller’s destroyer was sunk by a Japanese torpedo. After leading a survivor party ashore, the former Crimson Tide quarterback, seriously wounded and lacking strength, ordered his men to leave him behind. Astoundingly, Miller recovered. For the next thirty-nine days, Men regaled, he operated behind Japanese lines, “his insides torn, infected feet, almost half-starved, [and] his left arm badly shattered.” All the while, Miller had “killed more than two dozen of the enemy and secured invaluable data for Army and Navy intelligence.” The Japanese, Men intimated, never stood a chance.48

For sure, Miller’s story, and those like it, built upon a narrative of racial hatreds that seemed so very commonplace in the World War II Pacific theater. American veterans’ memoirs are replete with a visceral animosity toward their Asian foes. “Yellow bastards” and “yellow monkeys” were familiar epithets both during and immediately after the Second World War. In his classic With the Old Breed, as an example, Eugene B. Sledge shared his “rage and hatred for the Japanese beyond anything I ever had experienced.” After a fellow marine had been mutilated following one fierce battle, Sledge seemed to lose part of his humanity. “From that moment on,” he recalled, “I never felt the least pity or compassion for them no matter what the circumstances.”49 Another veteran of the Pacific shared Sledge’s hardheartedness. Herchel McFadden of the Americal Division noted how he and his fellow soldiers were “motivated to a high degree of anger and hate toward the Japanese… They placed no value on human life… They were not people.”50

Perhaps such depictions of the enemy made it easier to validate the battlefield worthiness of American GIs. If the “Japs” were to be killed “as if they were animals,” according to one vet, then it was far simpler for adventure magazines to focus on the “self-respect and dignity” of patriotic citizen-soldiers who “choke down their fear, and go forward, because a free man must.”51 Had not these warriors’ frontier forebears also fought against ruthless savages on the edges of civilization?

This hero-versus-savage narrative would need to be re-engineered after World War II as the Japanese transformed into a Cold War Asian ally. The adventure magazines proved equal to the task. Rather than fighting Japanese brutes, real men serving in Korea and Vietnam could employ their manhood to spur on reluctant Asian allies. Action related how a grisly American marine taunted his South Korean counterpart into action, ultimately creating a “deep comradeship” that was “fostered by mutual interest of two peoples seeking democratic freedom.” So influential had the Americans become that within Korean frontline bunkers, visitors could find pin-ups of “Liz Taylor, Esther Williams and other shapely Hollywood lovelies.”52 The next war found GIs similarly guiding their South Vietnamese charges. In one fantastical story from Male, an American sergeant even recruits a leper colony – their bodies “hideously eaten away by the rot of their disease” – and molds them into a “ferocious brigade of the damned” that bests the local Vietcong insurgency. Even the weakest raw material could be cast into an aggressive fighting force under American tutelage.53

In fact, given the right training and opportunities, any young man could become a hero. The pulps may have emphasized a kind of Cold War Rambo within their pages, the muscle-bound warrior who seemed more suited to war than peace. But men’s magazines also offered the hope and possibility that heroism lay within reach of most any working-class teen.

The Meritocracy of War

In men’s adventure magazines, war appeared as one of the most meritocratic endeavors young men undertook. Regardless of class, social status, or, on very rare occasions, race, anyone could be a battlefield hero. The pulps fashioned manhood as a wartime accomplishment, a triumph of courage over fear, of self-sacrifice over personal interests. War became a solution to fears of effeminacy, a way to prove that nagging insecurities were wildly misplaced. Veteran Robert Rasmus illustratively recalled being a teen when the Germans invaded Poland in 1939 and looking forward to the glamour and excitement of war. As Rasmus, who served as an infantryman in World War II, shared with oral historian Studs Terkel, “I was a skinny, gaunt kind of mama’s boy. I was going to gain my manhood then. I would forever be liberated from the sense of inferiority that I wasn’t rugged. I would prove that I had the guts and the manhood to stand up to these things.” In short, boys could achieve their manhood by participating in war.54

With brave individuals at the center of pulp war stories, adventure mags presented clear examples wherein even the weakest boys could aspire to become “real men.” In 1956, Saga included a story on “frail” Rodger Young, the most “unwarlike a guy as ever won the Congressional Medal of Honor.” Only 5’3” tall and weighing 137 pounds, it went without saying, according to Saga, that Young “would not have been cast as the hero.” Yet Young did become a hero in 1943, assaulting a Japanese machine gun emplacement on New Georgia island in the Solomons after his patrol had been pinned down. Despite numerous wounds, the Ohio native attacked the enemy with hand grenades and allowed his comrades to safely withdraw before himself being killed. Two years later, songwriter Frank Loesser penned “The Ballad of Rodger Young,” an elegy quoted heavily not just in Saga, but in Life magazine as well.55

The same year Saga featured Rodger Young, another Medal of Honor recipient hit the pages of Battle Cry. This time, however, the story was autobiographical and intimated that even those who survived the test of battle did not return home unscathed. In “The Day I Cried,” national hero Audie Murphy recounted the emotional and psychological costs of fighting German troops in the European Theater of Operations (ETO) and losing a close friend. Only two inches taller than Young, Murphy also appeared an unlikely hero before the war. Yet his experiences suggested that physical size and strength mattered less on the modern battlefield than automatic weapons or field artillery. The account in Battle Cry, though, offered readers another often unexpressed lesson of war – the horrors of combat left long-standing emotional scars that needed as much attention as broken or amputated limbs. Murphy hoped that by being more honest with the public, he might help close the “great gap between those who fought and those who didn’t.”56

Such honesty likely did not register fully with anxious young readers who may have felt vulnerable to charges of being a “wimp” or a “sissy.” In most pulp stories, skinny intelligence officers from the US Navy performed miracles behind enemy lines, gaining valuable information on the Japanese for MacArthur’s headquarters.57 Or the hero might be a “freckle-faced kid” who won three Navy Crosses before receiving a Medal of Honor for leading his submarine to a record of tonnage sunk by a US naval commander in World War II. Guy magazine even showcased an American adventurer who “conquered China” in the early 1900s. While the article declared Homer Lea as “one of the bravest fighting soldiers the world has ever known,” his body clearly did not hold him back. “Physically, he was a skinny, nearsighted little man with a hunched back.” How many teen readers took heart that they too had Lea’s boldness stored deep inside them as well?58

Overcoming one’s physical traits clearly mattered in pulp storylines. For Men Only went so far as to share military doctors’ claims that men “most capable of heroics and winning medals sometime are also the ones most likely to show feminine traits.” Yet war also could resolve social shortcomings as well. In Saga, US Air Force Brigadier General Monro MacCloskey wrote about a “crew of misfits” in his squadron, some of whom had been “tagged ‘yellow’ by their comrades because they couldn’t brave dangerous combat missions.” Despite being called “cowards” – perhaps because of it – the men took on a dangerous mission over Italy which made heroes out of these “Gutless GIs.” Even a stateside KP potato-peeler, “and a poor one at that,” could go on to become one of America’s deadliest commandos in World War II. War apparently could solve any man’s defects.59

Not surprisingly, such aspirational stories did not include women, even though they were still serving on active duty in the Second World War’s aftermath. (The pulps also largely ignored the exploits of African American soldiers.) WACs and army nurses operated near the front lines in Korea, with a total of 48,700 women serving in the US armed forces by October 1952. The macho pulps, though, rarely incorporated these women’s voices. The same might be said for American culture writ large. True, the armed forces did target women in some of their recruiting ads, one navy poster declaring “Serve with Pride and Patriotism” as it showed an officer, nurse, and enlisted sailor, all three in uniform, all three slender and attractive. Yet, as Lisa Mundey demonstrates, most recruiting materials designed for women “downplayed the masculine aspects of military service.” Women thus were expected to retain their femininity in uniform while simultaneously not posing a threat to men seeking military service as a path toward manhood.60

Of course, there were costs to heroism in battle, and the pulps regularly heralded the soldier who gave his life in an attempt to save a buddy. Man’s Magazine showcased two downed pilots in the Korean War, Captain Wayne Sawyer and Lieutenant Clinton Summersill, who crashed behind enemy lines in January 1951. Both wounded, Summersill severely, neither officer gave up on the other. After an arduous trek through the worst of weather, they fended off hunger and enemy patrols before making it back to friendly lines. The effort, though, proved costly. Sawyer lost part of his left big toe, while Summersill, after returning to Walter Reed Hospital in Washington, DC, had both of his feet amputated at the ankles. Loyalty and sacrifice went hand-in-hand.61

It was in these stories of self-sacrifice that the band of brothers myth took full form. Separated from society and women – there were no sisters in this martial family – male soldiers supposedly bonded together in ways unknown to the civilian world. Take, for instance, Staff Sergeant George Peterson, who died near Eisern, Germany saving his company from a relentless enemy attack. To Battle Cry, Peterson had “made his rendezvous with destiny” and proved “that the supreme, most perfect sacrifice is one of love, not hate; of life not death.”62 Such a fidelity to one’s soldierly brothers clearly touched an emotional chord with many future Vietnam veterans. John Ketwig knew his wartime friendships were special, just “as the strongest steel is tempered by fire.” Likewise, Phil Caputo believed that comradeship “was the war’s only redeeming quality,” even while acknowledging that it “caused some of its worst crimes – acts of retribution for friends who had been killed.” Might it be that despite claims otherwise, wartime kinship was, in fact, subject to impeachment?63

It seems feasible that perceptive readers may have seen something less than heroic in these stories. Without question, the band of brothers allowed men to share their fears and anxieties as long as they continued to perform in combat. Yet sanitized versions often omitted the less humane aspects of combat. Far from celebrating war, famed correspondent Ernie Pyle instead wrote sympathetically of “men at the front suffering and wishing they were somewhere else.” Medal of Honor recipient Audie Murphy felt “burnt out, emotionally and physically exhausted” after the loss of a close buddy. Rather than encouraging deep friendships or offering the chance to become a popular combat hero, war ended up depersonalizing many of those who fought, through either sheer terror or abject boredom.64

Moreover, a far less appealing attribute lurked just below the surface of popular storylines. What if war traumatized the soldier, disturbed his moral sense of right and wrong? In its tribute to Private First Class Patrick L. Kessler, who received the Medal of Honor for his actions in Italy, Bluebook lavished praise on this seemingly average GI Joe. The article described Kessler as “sociable with a liking for almost everyone without aggressive instincts.” Coming under fire near Ponte Rotto, Italy, though, the young Ohioan transformed – “he suddenly became a killer. Cold, calculating, implacable.” According to Bluebook, “White-hot fury burned in Kessler as he saw [his] platoon being decimated.” And while Jack Lasco described him as the Sergeant York of World War II, the pulp author also noted that Kessler went “battle mad” as he killed a number of German soldiers. If war had the capacity to turn any young boy into a heroic man, Bluebook implied war might also turn them into psychotic killers.65

Indeed, at the tail ends of both World War II and Vietnam, civilian anxieties arose over reintegrating broken soldiers back into society. One sociology professor even worried that World War II vets could become a “threat to society” if they were not properly “renaturalized.” William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives, which won the Academy Award for best film in 1946, equally dramatized the challenges of wartime veterans assimilating into families and small towns that appeared to have moved on without them during the war. All the while, women’s magazines urged their readers to be more supportive at home, “to return to a docile domesticity to placate their wounded men.”66

Men’s adventure magazines, however, rarely touched upon the returning veteran. Rather, the major theme in wartime stories – “I was somebody” – allowed men to retain their individuality and to be inspired by acts of heroism on the modern battlefield. As one infantry lieutenant serving in Korea shared with Man’s Life, “There is no other job in the world that can give a man the type and degree of satisfaction that a man gets when he knows the outfit is depending on him to protect it.”67

Such tales certainly contested the reality of industrial, mass warfare as a dehumanizing experience. In truth, war proved far less ennobling than young boys anticipated. Replacements came into units and were killed before anyone knew their names. Frontline soldiers often felt expendable. Killing and dying extracted a heavy emotional toll. As the first major psychological study of the World War II soldier found, a “fundamental source of strain was the sheer impersonality of combat.” Any young man might become a hero. But plenty more saw only the very worst war had to offer.68

The Ugly Face of War

When American soldiers and marines died in war movies throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, their deaths were quick, painless, and often bloodless. Their bodies remained clean and whole. Harold Russell’s character in The Best Years of Our Lives may have lost both of his hands in war, but we never see Homer’s devastating injury take place, only his painful reintegration back home in Boone City.69

Men’s adventure magazines similarly focused on the individual triumphs of war, rather than its bloody costs. Such narratives arguably held deep consequences for young recruits conditioned to think about war in idealized ways. When fighting failed to live up to their lofty expectations, when the shock of combat impacted soldiers unexpectedly, the results easily could manifest as post-traumatic stress (PTS). Although PTS was not part of the contemporary medical lexicon – physicians and commanders generally used the term “battle fatigue” – its symptoms were readily identifiable to doctors and more than a few pulp writers.70

The May 1953 issue of Action, for example, featured a look at GI marriage problems from psychologist R.C. Channon. The piece noted that “Often the hell of war causes soldiers to change their personalities.” To Channon, if the wife was “not as meticulous in the execution of her household chores,” she might exacerbate her husband’s mental problems. Even worse, however, Channon found that some Korean War veterans had experienced impotency, a “delayed reaction” to being on the battlefield. Surely quite a few young readers were taken aback in learning that this “sexual maladjustment” was part of war’s supposed man-making experience.71 They likely wondered if they too were susceptible to the “silent killer” of “war neurosis,” as detailed in a full-length essay in Real Combat Stories. Battle Attack went so far as to publish a piece titled “Are Heroes Psycho?” The article quoted one psychologist who found outstanding combat soldiers to be “hostile, emotionally insecure, extremely unstable personalities who might well be termed clinical psychopaths.”72

Clearly, something was amiss. John Wayne did not act in such antisocial ways. He was a hero, not a psycho. The dissonance must have been unnerving for teens brought up on more romantic versions of war in popular movies and comic books. Occasionally, though,the macho pulps did run stories sharing the ugliness of war, setting them apart from other pop culture venues. Despite the predominant themes of individual heroism and triumph, men’s magazines did shed light on both the moral and the physical injuries sustained in combat. For veterans dealing with their own PTS or loss of limbs, such articles may well have let them know they were not alone. Other veterans also felt vulnerable, bore wounds, or found war less dignified than advertised.73

In some cases, the pulps highlighted physical injuries. Male, for instance, published a photographic essay of a World War II soldier with a shrapnel wound in his left eye. The grisly photos included doctors probing and saving the eye, as well as bloody bandages and “dead flesh” on the operating room floor. In other cases, as in a Saga essay on Medal of Honor “heroes,” the magazines briefly alluded to the emotional damage suffered by veterans. One medal recipient acknowledged an often unspoken aspect of the military valor so romanticized in the macho pulps. As Cecil Bolton shared, “I hate to recount the action because I still have bad dreams about it.” If Saga was correct in arguing that a “genuine act of courage is an act of giving, not taking,” then these men seemed to have surrendered a permanent part of themselves on the field of battle. Surely marine E. B. Sledge would have agreed, recounting in his memoirs that “something in me died” on Peleliu island during the Pacific War fighting.74

While Fury’s 1959 account of Peleliu hardly captured the same horrors as did Sledge, other tales contested the notion that Americans always defeated their enemies in battle. A story on one of the US Army’s first World War II battles at the North African Kasserine Pass noted bitterly how “green, inexperienced” GIs were “blooded,” “mauled,” and “slaughtered” by Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps.75 Two separate articles on the “blunder at Anzio beachhead” in Italy were even less complimentary. One, from Battle Cry, stressed the futility of one of the war’s biggest stalemates. Miserable soldiers “griped and complained, went on dirty little patrols that accomplished nothing, and tried to make themselves a little less uncomfortable.” In its Anzio account, Men resentfully asked who was responsible for throwing 40,000 GIs “down the drain.” There seemed plenty of blame to go around. On these nightmarish battlefields, few heroes arose for the pulps to valorize, leaving behind an awkward evaluation of war as a man-making endeavor.76

Not surprisingly, the stalemated fighting in Korea offered further examples of war’s ugliness. The legacy of America’s first “limited war” sits uncomfortably beside that of World War II, for the Asian conflict left behind no clear winners, a host of GIs wondering why they were fighting, and a swath of destruction across South Korean society. To pulp writer Mario Puzo, Korea was “the non-fun war.”77 It certainly seemed that way in many magazine articles. According to one story on combat there, “It’s rain and mud, cold and misery. It’s blood on your bayonet and murder in your heart. It’s a lousy way to live – and a hell of a way to die.” Accompanying photographs displayed bearded GIs with sunken eyes: “always there is the face of pain and grief.” Another autobiographical story from Real Men, where soldiers fought off enemy troops with their fists, spoke of “kids who bled from ugly wounds,” the veteran-author sharing that he was haunted by “bloody nightmares.”78

If young boys aimed to spy a glance at war’s heroism or veterans sought to alleviate their own postwar anxieties, more than a few Korean War stories surely left them wanting. Battlefield published an essay on how North Korean captors massacred American prisoners of war, the GIs suffering from infected wounds, dropping from lack of food, the victims of bullets and bayonets. The magazine also ran a photo essay on “the look.” The sullen, dark-eyed faces of GIs stare out to the reader in images far different than the bold illustrations adorning the magazines’ covers. With the “look” came “Exhaustion. Sheer, utter, complete exhaustion. And bitterness. Always bitterness.” Battlefield told its readers not to pity these men because they were heroes, “every mother’s son of them,” but the price for that heroism seemed steep indeed.79

Utter exhaustion, however, was one thing. Losing one’s genitals was quite another. While the macho pulps heightened men’s fears of being emasculated at home, they also ran stories of soldiers literally being castrated in war. Challenge shared the frightening tale of Sergeant Wally Smith, who was wounded on D-Day, the “spurting blood vessels in his groin” clamped and tied off before his “organ had to be amputated.” After six operations, doctors had created a “neo-penis” for Wally, and eighteen months later, he left the military “with his virility fully restored.” To demonstrate the sergeant was no different from any other husband, the article made sure to point out that he was happily married with two normal, healthy children.80

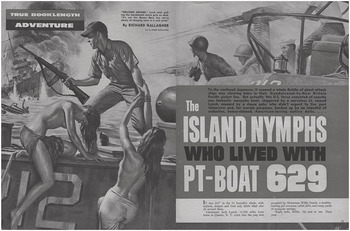

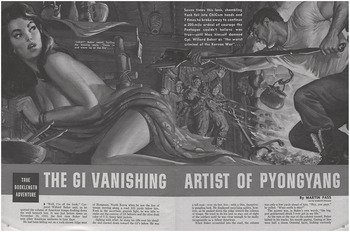

Of course, men’s magazines likely would have sold few copies if editors had placed graphic and candid images on their covers. Rather, they marketed sensationalist modern artwork from what one cultural commentator described as “geniuses of a populist hyperrealist style.” In these artists’ hands, illustrations depicted war as dramatic and compelling, with battlefields frequented by beautiful women eager to please the male protagonist. Mort Künstler, for example, helped pulp writers tell their stories with striking cover paintings and alluring interior illustrations. Trained at Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute, Künstler highlighted both the warrior hero and the sexual conqueror. The cover of Male’s January 1964 issue shows a muscular, cigar-chomping American POW leaning over his diminutive Japanese captor, leaving little doubt who holds real power in this prisoner camp. To accentuate Richard Gallagher’s “The Island of Sea Nymphs Who Lived with PT-Boat 629,” Künstler brought eye-catching sexuality to the forefront of his work. As an enemy ship sinks in the background, a young naval lieutenant pulls aboard two bare-breasted natives, their “honey-skinned” torsos glistening from the ocean water.81

Fig. 2.6 Male, December 1962

Another popular artist, Bruce Minney, graduated from the California School of Arts and Crafts before packing up for New York to make his way as a freelance illustrator. Like Künstler, he contributed artwork that now seems indispensable to the pulp genre. For one Vietnam-era story, Minney drew a lone American GI attacking a Vietcong anti-aircraft gun pit. With grenade in one hand and bayonet in the other, our hero straddles the gun’s tube, eliciting visions of Slim Pickens riding an atomic bomb in the penultimate scene of Dr. Strangelove, while the guerrilla fighters cower below, intimidated by the GI’s audacity. In another example, Minney teamed with Mario Puzo for a Male book bonus on a jungle breakout from the “Amazon’s Captive Girl Pen.” Here, “lush, silken-bodied females” are rescued from a “lust-crazed” South American warlord. In the story’s illustration, Yank adventurers save bikinied women from the back of a truck-bed cage, the driver riddled with American bullets. Minney’s visual suggested the heroes would be justly rewarded not long after they make their escape.82

Still other artists brought a wealth of talent and experience to the pulps. Norman Saunders began illustrating back in the 1930s, often serving as his own model for Nazi commanders or frontier cowboys. Of note, Saunders also drew the “Mars Attacks” trading cards released in 1962 by Topps Bubblegum Company. Rudy Nappi illustrated covers for the Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys books, while also contributing interior work for Male stories on World War II GIs in luscious Pacific settings. Artist Charles Waterhouse served as a marine and was wounded during the battle for Iwo Jima before attending classes at the Newark School of Fine and Industrial Arts. Finally, Samson Pollen had spent time in the Coast Guard Reserve and painted in genres ranging from adventure magazines to teen books and romance novels. In one illustration for a Male adventure story on the Korea War, Pollen’s white t-shirted hero breaks into a Chinese bunker, three undersized soldiers trembling in the corner. A nude woman with Eurasian features, only slightly covered by bedsheets, fills the entire left side of the magazine.83

It seems doubtful many Korean War bunkers were occupied by such beautiful women, and perhaps that was the point. Dramatic artwork could serve as a useful counterpoint to those pulp stories honest enough to share the ugliness of war. Paired with stirring first-person accounts, the artists might also help pulp readers deal with the larger strategic impasse in Korea. Focusing on beautiful women or battlefield successes allowed men’s magazines to shift the narrative away from what had clearly turned into a stalemated war. Foreshadowing later disappointments in Vietnam, the “limited” Asian conflict left Americans wondering why they could not translate all their massive power into a clear-cut strategic victory. Thus, as the deadlock in Korea became increasingly unpopular, the pulps centered their attention on satisfying heroism at the tactical level, even as they occasionally revealed the darker side of war. Heroic tales might contest claims, like those from one US senator, that Korea had “shown us how weak we are, and how strong the enemy is.”84

Fig. 2.7 Male, February 1962

While the pulps did not shy away from the hard fighting in Korea, they nonetheless flaunted the common soldier’s bravery. In “Hell on No-Name Hill,” American grunts stave off Soviet-made T-34 tanks, Korean snipers, and hordes of enemy infantry to protect a major road running into Seoul.85 Male’s account of Captain Bill Barber surely disputed allegations that American men had turned soft. Fighting near the Chosin Reservoir in North Korea, Barber “engineered the greatest no-surrender stand since Valley Forge.” With temperatures well below zero and surrounded by more than 1,000 Chinese troops, Barber led his marines with unflappable determination, even refusing to be evacuated after being shot in the legs. When a lieutenant requested Barber head back with the wounded, the captain replied, “Listen, kid, I came to fight.” By story’s conclusion, Male ensured its readers knew who had come out of the battle victorious. “Everywhere the enemy was dying, fleeing, surrendering…”86

The heroism of men like Barber, for which he received the Medal of Honor, surfaced in other Korean War stories as well. The weather always seemed bone-chillingly cold. Americans almost always found themselves surrounded by a greater number of “Chicom” forces. Stalwart GIs and their officers never failed to hold their positions. When one veteran-author detailed the fighting at Chipyong-ni, he shared how the “cries of the wounded and dying rose above the battle noises.” A GI next to him took a rocket fragment to the belly. Another was blown off a tank by a mortar shell. Yet there is little emotional distress in his tale, except an admission that his unit had taken “heavy causalities – very heavy casualties.”87

Such stoic heroism appeared in more than a few contemporary books on Korea, if not as much in combat films. Movies like Pork Chop Hill (1959) proved far less celebratory than Wayne’s The Sands of Iwo Jima. The Gregory Peck drama of GIs holding a worthless piece of terrain against repeated Chinese attacks suggested that the ugliness of war could not so easily be dismissed. But other venues could supplement the dominant narrative within the pulps. S.L.A. Marshall’s 1953 The River and the Gauntlet, for example, valorized the GI, even as the author maintained that the theme of his book was “not one of tactical victory, but of adversity.” Still, Marshall lavished praise on those who served as “an example of courage, unity of action in the face of terrible odds, and the ability of native Americans to survive calamitous losses and give back hard blows to their enemies.”88

Marshall’s unforgiving nativism equally was reflected in Andrew Geer’s The New Breed from 1952. This thrilling account of marines in Korea surely would have made many a pulp writer envious. In one episode, an infantry battalion suffers fifteen killed, thirty-three wounded, and eight missing in action after a hard battle. Far from being weakened by the ordeal, the unit comes out “physically tough and psychologically hard.” Moreover, Geer’s depiction of the enemy ensures his American heroes are battling a worthy, if not wicked, foe. The Chinese soldier has the “Asian stamina and mental fortitude to withstand the harshest demands of command, conditions and climate.” And because he has a low standard of education and has been taught “blind obedience,” he will follow his commanders to the death. Thus, there is much to cheer when, in I.F. Stone’s “hidden history” of the war, we read of this heartless enemy being “slaughtered in astronomical numbers.” Yes, fighting conditions in Korea might be horrendous. But how many young readers aspired to be just like the brave American marine who yelled “Let the bastards have it” as he opened fire with his heavy machine gun on the communist monsters?89

In the end, how young teens imagined their fathers’ wars depended in large part on how pop cultural mediums and veterans themselves relayed America’s wartime experiences to the next generation. Men’s adventure magazines most certainly helped transmit certain values from fathers to sons. As one advertisement declared, “A Boy Needs a Dad He Can Brag About!” In the postwar era, it seems plausible that many working-class kids saw their fathers as “the strongest, smartest, bravest guy in the world” because of their military service in World War II or Korea.90 There, they had affirmed their manhood as patriotic citizen-soldiers. Sons no doubt built expectations based on these gendered codes so artfully displayed in the pulps. And while adventure magazines clearly targeted men, the number of interior ads selling rocket ships, flying helicopters, plastic toy cars, and “monster-size monsters” suggested that pulp editors knew younger readers were consuming their products, perhaps just as much as their dads.91

The depiction of war within men’s adventure magazines ultimately might be seen as both a product of and a contributor to how fathers taught their sons the value of uniformed service in making them men. Surely, not all working-class families subscribed to such notions of martial glory. Yet in the Cold War era, many fathers did worry about making men out of their boys, some compulsively so. The social reality in the macho pulps thus not only helped establish the collective memory of the “greatest generation,” but also influenced how Vietnam-era soldiers defined their own brand of masculinity thanks to what was passed down to them. As one West Point graduate recalled, “we were taught and mentored by an exceptional cadre of seasoned veterans who fought in World War II or Korea… These great men molded our characters, shared their wisdom, and taught us the hard lessons of warfighting paid for by the blood of their fellow soldiers.”92

These same great men, however, far too often avoided the truths of war’s uglier side. So too did men’s adventure magazines. The pulps constructed a battlefield memory that relied mostly on an imagined reality. Death was clean. Men overseas rarely if ever took out their frustrations on the civilian population. Americans never shrank under the pressures of combat, no matter how much the odds were stacked against them. But, as Steven Dillon suggests, what “looks like hard-minded heroism might be an anxious shield flung up against female sexuality.” With American women seemingly on the warpath to oppress men at home, perhaps these allegedly embattled males could look elsewhere for sexual satisfaction and domination. Viewing the macho pulps from this angle reveals how young men in the Cold War era fantasized not just about heroic combat, but also about sex and the availability of the erotic, sensual “Oriental” woman.93