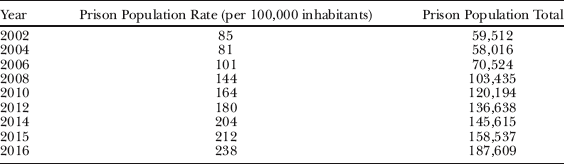

Since 2002, the year when the Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power, the Turkish criminal justice system has undergone major transformations. Between 2002 and 2016, the number of incarcerated people increased from around 60,000 to more than 187,000, raising the rate of incarceration from 85 to 238 per 100,000 people, which places Turkey on fifth place among European countries in terms of incarceration rate (International Centre for Prison Studies 2016; Turkish Statistical Institute 2016) (see Table 1). Interestingly, this upward trend has stayed more or less constant during the entire period that AKP has governed the country, irrespective of the dose of authoritarianism that the party has used, which significantly increased after 2009. To cope with this dramatic rise, the government built 105 new prisons, appointed more than 5,000 new judges and prosecutors and institutionalized new mechanisms of control, such as probation and electronic surveillance of released criminals, for the first time in the county's history.Footnote 1 However, none of these measures has conclusively resolved the recurring twin problems of the criminal justice system—i.e., overpopulation of prisons and very heavy workload of courts. A recent report shows that despite new prison construction there are currently only 565 beds available for new prisoners.Footnote 2 Moreover, the number of cases brought to courts increased from 4.7 million in 2,000 to 6.5 million in 2012. Turkish judges are responsible for 1,078 cases annually whereas the average in European countries is only 200 (Ministry of Justice 2011:22).

Table 1. Prison Population Rate in Europe (2016)

Source. International Centre for Prison Studies (2016).

The traditional mechanism of dealing with the overburdened criminal justice system and overcrowded prisons in Turkey has been the issuance of general amnesties for people convicted of criminal offences. In fact, with 157 amnesties since 1923, 11 of which were general amnesties, the country tops the world in the number of amnesties passed (Ankara Chamber of Commerce 2004; Reference Cengiz and GazialemCengiz and Gazialem 2000).Footnote 3 Amnesty, in a sense, acted as an “emergency button” to be utilized whenever the system got clogged (Reference Kocasakal and KiziroğluKocasakal 2010: 94). Even though the surge in incarceration rates since 2002 exacerbated the systemic challenges to the criminal justice system, the AKP has strongly rejected amnesty as a policy of alleviating these structural problems. Leading party members have repeatedly claimed that the state will no longer grant amnesty to criminals and that a new general amnesty is entirely out of question. As the founder and the uncontested leader of the party, Mr. Erdogan has stated during his time as Prime Minister (PM), “For a long time, I've been saying that there is no such thing as general amnesty on our agenda. I have said it so many times…There is no such thing, definitely not”.Footnote 4

What makes the Turkish experience with amnesty more interesting is the fact that even though amnesty is granted across the world almost exclusively for “political crimes,” particularly during periods of regime transition or collapse (Reference Lessa and PayneLessa and Payne 2012; Reference MallinderMallinder 2008; Reference Popkin and BhutaPopkin and Bhuta 1999), Turkish amnesties have rarely covered political crimes, or “crimes against the state” until the AKP period.Footnote 5 AKP's approach, however, reverses this past trend and stresses that the state can only “pardon” offences committed against itself—i.e., political crimes and should not interfere when the criminal act concerns another person's right to life or property. Since the government has not granted any form of amnesty yet, AKP's approval of political amnesty remains so far at the discursive level. However, we argue that this discursive shift regarding political amnesty is significant because it amounts to a redefinition of the politically legitimate boundaries of amnesty, which makes it quite likely for a political amnesty to be issued in the future.

In this article, we use the changes in the Turkish amnesty field to understand how a developing country government committed to a “tough-on-crime” agenda manages the increasing tension between the instrumental requirements of its overburdened criminal justice system and its ideological and political commitment to increased punitiveness. Given the total prison population stood at a staggering 187,609 and the rate at 238 by April 2016, the rise in prison population in the AKP period has been so dramatic that a recent report stated there are only 565 empty beds left in existing prison complexes even though 105 new prisons with 109,430 capacity have been built since 2006.Footnote 6 Therefore, a close analysis of the Turkish case can provide important clues as to how such developing country government's deal with the various financial, administrative, and political costs that increased punitiveness brings forth. These governments largely lack the financial, technological, and administrative resources available to advanced capitalist countries to implement the kind of “neoliberal” penal policies and reforms that we observe in advanced capitalist contexts. When they do, as in the Turkish case, they create serious problems and bottlenecks for the system. Observing how they implement the reforms and manage the systemic problems the reforms bring enhances our understanding of how neoliberal penalty works in developing country settings. As such, this analysis contributes to the growing literature on the systemic challenges and tensions facing criminal justice systems in developing country settings (Reference ShahidullahShahidullah 2012).

More specifically, three significant questions emerge from the Turkish experience with amnesty: First, why did the AKP steer away from past practice of using amnesty to resolve the systemic problems of the justice system such as overcrowding and case overload? Second, given the phenomenal rise in the numbers of people entering the criminal justice system, what alternative mechanisms does the government utilize in dealing with these structural problems? Finally, why did the AKP government redefine the politically legitimate boundaries of who and what can be pardoned by the state to make it theoretically possible for the state to pardon crimes against itself, a historically rare practice in Turkey? We argue that AKP's strict anti-amnesty position is part of the larger neoliberal penal regime that the party has been constructing since it took office. Based on the existing literature on how criminal justice systems around the world have transformed under neoliberalism we characterize an ideal-typical neoliberal penal regime around three main elements: increased punitiveness, holding individuals ultimately responsible for criminal acts, and a rationalized managerial approach to deal with crime and increased incarceration. No doubt, different countries institutionalize these in varying degrees. As we show, AKP's criminal justice reforms have brought the Turkish system closer to an ideal-typical neoliberal penal regime, which led to the drastic increase in the numbers of people entering the criminal justice system and introduced major challenges to the system. Yet the “ethos” of this neoliberal regime is incompatible with relying on extraordinary measures such as a large-scale amnesty in resolving these challenges. Releasing convicted offenders would signal the weakness and incapacity of the state in dealing with the consequences of its own punitive policies and would fundamentally violate the idea of holding criminals ultimately responsible for their actions. Therefore, not using amnesty even when the conditions are calling for it is an integral part of the neoliberal penal regime the government has been constructing.

Refusing to pass a general amnesty, however, amounts to giving up a clear-cut and radical solution to the long-standing and systemic problems of the criminal justice system such as overcrowding in prisons and case overload for courts. AKP's main response to this dilemma has been utilizing alternative policies to ease the system such as institutionalizing probation and electronic surveillance, creating alternative mechanisms of dispute resolution, and quantitatively expanding the capacity of criminal justice institutions to cope with increased numbers. Significantly, most of these policies have been implemented with the full backing of the European Union (EU), which has always been highly critical of the Turkish criminal justice system. Thanks to such measures, the government has so far been able to alleviate the tension between increased punitiveness and an overloaded system but there is no guarantee that it will do so in the future. But as the government increasingly uses the judicial system to pacify and silence its opponents since 2009, and most evidently in the aftermath of the failed coup attempt in the summer of 2016 that led to the arrest of tens of thousands, the criminal justice system is once again likely to face insurmountable problems, which might lead the government to take extraordinary measures such as a comprehensive amnesty.

Central to all these transformations in the criminal justice system are the new ways in which the party secures legitimacy and support among the public—or what we call AKP's new populism. One of the central tenets of this new populism is the image of a strong and capable state that no longer relies on extraordinary measures and/or the suspension of existing laws to resolve structural problems. A general amnesty is precisely such an extraordinary measure that signals state weakness. Appearing tough on crime and successfully managing the consequences of increased punitiveness without passing a general amnesty fortifies the strong state image desired by the party leaders. The neoliberal penal policies we have discussed above, then, are a quintessential part of AKP's new populism. The elective affinity between this new form of populism and neoliberal penality has created a strong amalgam that reinforces the party's anti-amnesty stance.

AKP's new populism has also brought about the weakening of the idea of a paternalistic state that forgives its unfortunate citizens pushed to crime. In its place, we observe the solidification of a retributive state that refuses to forgive offenders. Significantly, this new conceptualization of the state and state—society relations solidified before the party began its relentless authoritarianism after 2009. The authoritarian turn after 2009 gave added impetus to the punitive and retributive state model, which helped the government in silencing all opposition through the judicial system. Of particular importance in this new ideal state is the emphasis placed on protecting victims’ rights. As we show, AKP leaders repeatedly emphasize that only the victims can forgive offenders, and that the state can only forgive crimes committed against itself, not against other individuals. This victim-centered view has strong roots in Islamic jurisprudence where the concept of kul hakkı, or the rightful share of a believer, largely shapes state—society relations. According to this legal tradition, the rights of believers lie beyond the domain of politics and are protected by God. When these rights are violated, the state must enforce the laws. As members of an Islamically motivated conservative party, AKP leaders are influenced by this religious dictum in their approach to the issue of pardon.Footnote 7 Because the nominally secular constitution in Turkey outlaws the codification and implementation of religious law, this shari'a-based concept has not been codified in law. But we argue that the anti-amnesty stance of AKP leaders is as much influenced by their religious worldview as their neopopulist desire to project a strong state image. The elective affinity between a certain religious worldview and a particular image of the state has generated a strong ideological and institutional reorientation in criminal justice policies, including the domain of amnesty.

Our research contributes to the literatures on neoliberal penality, law, and ideology and on state—society relations in three ways. The prevailing tendency in the literature about neoliberal penalty is to focus on the various ways in which states employ more punitive measures to deal with the socially and discursively constructed crime problem. Notwithstanding the importance of such works, we believe that how states forgive (and refuse to forgive) is equally important to understand as how they punish. Our research on the changing amnesty policies in a country undergoing aggressive neoliberalization fills an important gap in this regard. Second, the puzzling policy change in Turkey since 2002 offers us an excellent vantage point into how states with limited economic resources, such as Turkey, maintain their legitimacy as well as governing capacity at a time when they have decided to become more punitive. While a populist “tough-on-crime” policy increases the legitimacy and popularity of the government, the growing institutional and managerial problems that an overburdened criminal justice system presents decrease the government's capacity to govern effectively. It is empirically interesting to observe how the Turkish government deals with this dilemma in the absence of a general amnesty. Finally, the Turkish case is anomalic in the sense that it is the only country that has repeatedly used general amnesty as a regularized policy to manage the problems of the criminal justice system and has recently steered away from this policy.Footnote 8 As such, it deserves closer scrutiny.

The article consists of three parts. In the first section, we offer an analytical discussion of the three constitutive elements of an ideal-typical neoliberal penal system,—i.e., increased punitiveness, individual responsibilization, and managerial rationalization. The legal and institutional reforms by the AKP government have brought the Turkish criminal justice system closer to such an ideal type. Relying on amnesty to address systemic problems, we argue, goes against the core ethos and principles of this neoliberal penal regime. In the second section, we delve into the ideological and political roots of AKP's neoliberal penal reforms and argue that it is impossible to understand these reforms without paying close attention to the party's new, religiously motivated populist discourse and set of practices. Exploring this new populism with regard to its relationship to criminal justice policy and amnesty reveals a lot about state–society relations, and more particularly, about how the party constructs its legitimacy among the public. As we show, AKP's new populism is largely incompatible with the use of amnesty to release convicted criminals. On the contrary, it relies on the image of a punitive state that protects the rights of victims. We end the article with concluding remarks regarding the high degree of the politicization of law in Turkey, and what this implies for the long-term sustainability of AKP's criminal justice policies and amnesty politics.

Our findings are based on three main data sources: First are reports by the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) and other legal institutions about the problems of the criminal justice system and their proposed solutions. These include annual activity reports and strategic plans published by the MoJ, reports by parliamentary commissions and analyses by bar associations and other legal organizations. We collected all these official documents over 3 years (2014–2016) to better understand the recent changes in penal policies and reforms in Turkey during the AKP period. Our second source of data is in-depth interviews with legal professionals about amnesty as well as the general issues and problems regarding the criminal justice system in Turkey. More specifically, we interviewed representatives from the following organizations: Progressive Lawyers Association (Çağdaş Hukukçular Derneği); Human Rights Association (İnsan Hakları Derneği); The Association for Freedom of Thought and Educational Rights (Özgür-Der); Libertarian Democratic Lawyers Association (Özgürlükçü Demokrat Avukatlar Grubu); Nationalist Lawyers Association (Milliyetçi Avukatlar Grubu); The Platform for the Supremacy of Law (Hukukun Üstünlüğü Platformu); and Criminal Law Association (Ceza Hukuku Derneği). These organizations have all adopted strong and substantially different (and opposing) positions regarding about amnesty politics in Turkey on various public platforms. The ideological, political or jurisprudential basis of their support or criticism of the government's new stance on amnesty has helped us to map out the range of opinions on this controversial issue in the country. We also interviewed a professor from the Faculty of Theology at Marmara University on the topic of Islamic jurisprudence in order to better understand how Islamic law approaches the issue. The interviews lasted between 45 and 90 minutes and were all conducted in Istanbul between winter and fall of 2014. The final source of data we utilized is descriptive statistics on incarceration rates, prison populations, and caseloads of courts and judges compiled by the Turkish Statistical Institute. We collected these statistics over three years (2014–2016) to observe how the criminal justice system in Turkey has empirically changed in the AKP period. In addition to these official statistics from the national statistical institute of Turkey, we used the database World Prison Brief (WPB) published by the International Centre for Prison Studies (ICPS) in 2016 to access comprehensive and updated information about the Turkish prison system.

Amnesty Politics under a Neoliberal Penal Regime

Challenges and Perils: Penal Regimes in the Age of Neoliberalism

Using the “neoliberal” adjective to refer to a particular penal regime carries certain risks as the term is widely used, and abused, in social sciences and humanities to refer to a whole range of political, economic, cultural, legal, and spatial transformations without much analytical clarity and precision. There is even a problematic tendency among some academics to use the term as a shorthand for complex theoretical assertions that are usually not adequately explicated or discussed. Notwithstanding these risks, we still choose to use the term as an adjective to capture certain institutional, organizational and ideological transformations in penal regimes common to most countries in the last three decades. The first feature of a neoliberal penal regime is the adoption of harsher policies against criminal activities as well as looser definitions of what constitutes crime, leading to dramatic rises in the numbers of people entering the criminal justice system (Reference BeckettBeckett 1997; Reference GarlandGarland 2001; Reference PrattPratt 2002; Reference Simon, Stenson and SullivanSimon 2001; Reference WacquantWacquant 2000). The use of harsh mandatory sentencing for victimless crimes; the spread of “broken windows policing”; the unprecedented rise in spending on policing and surveillance; and the constant need for new carceral institutions to discipline, punish or rehabilitate offenders are but some of the manifestations of this “penal turn.” Whether used as a policy to contain the ‘dangerous classes’ (Reference SimonSimon 1993; Reference WacquantWacquant 2001, Reference Wacquant2009) or to resolve the legitimacy crisis states face during a time of drastic budget cuts, austerity measures and social protests (Reference GarlandGarland 2001), the rise and rise of the “security state” is forever transforming how states define, manage and punish crime and criminals to resolve the problems of social order and reassert their right to rule.

Concomitant with increased punitiveness is the pervasiveness of the ideology of individual responsibilization, which views offenders as rational actors making choices. Following Reference FoucaultMichel Foucault (2008), a lot has been said about how the ascendance of the free market ideology and institutions has been accompanied by the discursive as well as practical construction of a new kind of subject with the capacity and the responsibility for self-optimization and self-care (Reference RoseRose 2007). Such “biopolitics” demands from the free individual self-actualization while simultaneously denying her the resources and opportunities that used to be provided by various sources, including the government, in earlier periods. When a person fails to make the most efficient and rational choices in life, thereby realizing her true potential as a human being, this failure is treated as an outcome of some kind of moral and/or talent deficiency with the person that can only be addressed through creating the right incentives—i.e., carrots and sticks). Finding its manifestations most clearly and succinctly in rational choice theory in the social sciences, this ideology of individualization has brought about enormous changes in the definition and management of crime and criminality (Reference HarcourtHarcourt 2005, Reference Harcourt2011).

For the “new penology,” a criminal is no longer a person pushed to crime due to socio-psychological or economic circumstances but a person like any other who invests and expects a certain profit and risks making a loss out of the criminal behavior (Reference BeckettBeckett 1997; Reference Feeley and SimonFeeley and Simon 1992; Reference GarlandGarland 2001). Criminality, likewise, is no longer seen as the manifestation of some sort of “social disorganization” or the failure of society to properly integrate its members into the mainstream and inculcate them with the right values. Criminality comes out of “crimogenic environments” that can, and should, be contained and controlled (Reference Feeley and SimonFeeley and Simon 1992: 455; Reference HarcourtHarcourt 2005). This substantial paradigmatic shift with respect to how crime, criminals, and criminality are viewed leads to the institutionalization of an actuarial logic that codes certain types of people and places as more crime-prone than others, and diverts increased resources to surveying and patrolling such people and places. The end goal of crime control institutions is no longer the rehabilitation of offenders or the restoration of social order but the minimization of risk through raising the cost of criminal acts, thereby deterring the rational actor from violating laws (Reference Morgan, Duff, Marshall, Dobash and DobashMorgan 1994). The responsibility, therefore, falls entirely on the free subject who must pay for his ill choices when caught. As Reference RoseRose (2000: 337) puts it, “The pervasive image of the perpetrator of crime is not the juridical subject of the rule of law, nor the bio-psychological subject of positivist criminology, but the responsible subject of moral community guided by ethical self-steering mechanisms.”

This ideational shift in how crime and criminals are constructed lends itself to the belief that the pervasive crime problem can best be handled through managerial rationalization and technological sophistication. Creating comprehensive databases and predictive algorithms, adopting proactive and preemptive policing strategies, maximizing information flow across different agencies, speeding up the processing of cases, minimizing case overload, and, finally, maximizing resources to accomplish these tasks have increasingly become the dominant goals of criminal justice institutions. Furthermore, the number of people they put behind bars, independent of whether this actually decreases crime rates (Reference HarcourtHarcourt 2011), now measures performance of law enforcement agencies. This obviously raises the incentive of law enforcement agencies as well as prosecutors to become more indiscriminate in whom and what they charge and convict. As numbers of people entering the system expand so does the legitimacy of institutions competing to be the “toughest on crime” (Reference BellBell 2011). Moreover, as the push for organizational efficiency and managerial rationality replaces sociological analysis and scientific empiricism, criminal justice institutions attain more autonomy from politics. All this results in the domination of the political field by what Reference GarlandGarland (2013) calls the “penal state.”

The rise of the penal state, however, creates a major problem. As the penal net widens, the criminal justice apparatus becomes overburdened with cases as well as convicts, requiring the constant expansion of the penal apparatus—i.e., a kind of self-feeding mechanism. This obviously creates financial as well as administrative problems that cannot be alleviated by managerial rationalization alone (Reference SimonSimon 2016). Outside of advanced capitalist contexts, where there are fewer financial, logistical, or managerial resources available to criminal justice institutions, the shift towards increased penalization creates problems that are even more serious. Turkey is an exemplary case in this regard given the scale, scope. and nature of the transformations in criminal justice policies that led to a major upsurge in incarceration rates as well as significant institutional restructuring. Under the new penal regime, old mechanisms of managing the problems of the system, such as general amnesties, are no longer available to policy-makers in the country, while new institutional arrangements and remedies are incomplete and insufficient at best. Therefore, the reversal of amnesty politics in Turkey under AKP rule captures the motivations, tensions, and contradictions of constructing a penal state by an authoritarian government in a developing country. In the remainder of the paper, we analyze the main institutional structures and policy measures that brought the Turkish system closer to the neoliberal ideal type, examine the alternative measures developed to deal with the structural problems of the system—i.e., overcrowding and case overload, and discuss the political and ideological motivations behind these policy changes.

The Penal Turn in Turkey and Its Contradictions

In this section, we detail the transformations in the Turkish penal system since 2002 under the AKP government that have made the system more aligned with the three core principles of an ideal typical neoliberal penal regime—i.e., increased punitiveness, individual responsibilization, and managerial rationalization. Before we start the discussion, two caveats are necessary. First, neoliberal reforms in the Turkish criminal justice system did not begin in 2002. However, the scope and scale of the previous reforms were much more limited compared to the post-2002 ones. For example, in 1991 the Turkish government passed a controversial legislation to move political prisoners from ward-type cells to solitary confinement in order to break networks of resistance and solidarity among prisoners and thereby control them more effectively. The institutionalization of the F-type prison system, as it came to be known in Turkey, has radically changed prison life by not only isolating prisoners but also turning them into “rational calculators” who need to internalize a self-disciplinary order in order to “earn” favors from the prison administration that would make their life more bearable inside the cells (Reference Ibikoglu and WhiteIbikoglu 2013).

Implemented to better control political prisoners seen as a threat to the security of the state, this new prison system relies on the three tenets of a neoliberal penal regime in that it enhances managerial efficiency, increases punitiveness and imposes self-responsibilization on prisoners. Its scope, however, has been limited to political prisoners who constitute a minority among the total prison population.Footnote 9 Until AKP took office, the rest of the prison system remained mostly intact. Furthermore, the transition to this system was in no way smooth; a bloody confrontation took place inside the old prisons between prisoners resisting against their transfer to F-types and special operation forces of the Turkish armed forces that resulted in the death of 30 prisoners during the operation and 90 more as a result of the death fasts by prisoners and their supporters.Footnote 10 The AKP government, on the other hand, undertook a much bigger transition in scale and scope in the criminal justice system and succeeded to pass its reforms with minimal difficulty or resistance. While neoliberalizing attempts before AKP were limited to a small segment of prisons (i.e., political prisoners), AKP's reforms extended to the entire criminal justice complex, including prisons, policing, and dispute resolution mechanisms. As such, it is appropriate to conceptualize AKP's penal policy as an important break from the past even though initial steps were taken before AKP took office.

Our second caveat is that even though the post-2002 reforms brought the Turkish penal system closer to the neoliberal ideal type we have defined, this transition is certainly not complete. There still remain many aspects of the Turkish penal regime that go against an ideal-typical neoliberal model, which is a highly rationalized system with minimal degree of politicization of law or minimal role for judiciary discretion. Turkey is far from such an impersonal and rationalized model. The three controversial lawsuits against Kurdish politicians and high-ranking military officials (the KCK, Ergenekon, and Balyoz trials in 2009, 2008, and 2010, respectively), the backlash against judges and public prosecutors behind the major corruption probe against high-ranking government officials in 2013, and the massive purge of civil servants after the failed coup attempt in 2016 are showcase examples of how the AKP government uses law to repress opposition. The Turkish criminal system, in other words, does not work like an efficient, self-referential, and impersonal machine. Notwithstanding these shortcomings, we still argue that AKP's reforms have caused significant qualitative changes that have widened the penal net, rationalized the administrative logic of institutions, and created positive and negative incentives for self-responsibilization and discipline among the convicted. Refusing to pass a general amnesty, even when the system works at over-capacity, only makes sense in tandem with these qualities.

i) The Rise of Punitive Policies in the Turkish Penal System

AKP came to power in 2002 in the aftermath of a devastating economic crisis that decimated the Turkish economy in 2001. Mobilizing disgruntled voters with a promise of wide scale change and stability, the newly formed Islamist party secured enough parliamentary seats to form a single-party government after more than a decade of unstable coalition governments. Thanks to a successful IMF-backed economic program as well as the particularly favorable global economic context that lasted until 2008, the economy recovered rapidly and the nominal GDP per capita in the country almost tripled. This economic success brought with it increased political support for the party, which by 2007 received 47 percent of votes in the general elections, a significant rise from the 34 percent in 2002. Furthermore, the party also took some bold steps in improving civil and political rights in the country that resulted in the official beginning of accession talks with the EU in 2005, five decades after Turkey first applied for membership. That the same period also witnessed the most dramatic increase in the numbers of people entering the criminal justice system is puzzling and deserves an explanation.

When AKP came to power, the total prison population stood at 59,512 and the incarceration rate at 85 per 100,000 people. By 2015, these numbers raised to 158,537 and 212 respectively and in 2016 (April), the total prison population stood at a staggering 187,609 and the rate at 238 (see Table 2). Interestingly, this upsurge in incarceration rates began at a time when the AKP was passing numerous democratic reforms in line with the requirements of the European Union (EU) for Turkey's membership. The kind of reforms and institutional mechanisms to the criminal justice system that have contributed to the increased punitiveness observed during AKP's rule have actually fulfilled EU's requirements from Turkey in reforming its criminal justice institutions. In other words, the democratization drive of AKP since 2009 and its criminal justice reforms do not contradict each other and have both been supported by the EU. However, after 2009 the government has largely given up on its democratization drive yet is increasingly exploiting the reformed criminal justice to crackdown on all forms of opposition to its authoritarian rule.

Table 2. Prison Population Rate & Prison Population Total in Turkey (2002–2016)

Source. International Centre for Prison Studies (ICPS) & Turkish Statistical Institute (TURKSTAT), 2016.

As part of its overall reform agenda, AKP legislated a new Penal Code in 2004 that contributed to the increase in two ways: (i) increasing mandatory sentencing for most offences, and (ii) defining new types of criminal offences. Before the new law came into effect, the discrepancy between the given sentence of a convicted person and the actual time s/he served had been larger. The new law closed the gap between the sentence and the actual time served in prison (Reference ErdoğanErdoğan 2005: 9). As a result, the prison population surged. The second way in which the new law contributed to the rise is the introduction of new criminal offences such as cyber-crimes, crimes against the environment or illegal construction of dwellings.Footnote 11

Another impetus behind mass incarceration is the sizable increase in the budget and personnel of law enforcement agencies to create a more effective and more vigilante police force. Between 2006 and 2014, the police budget more than tripled to reach 16.3 billion TL (Reference YentürkYentürk 2015). Together with budget increase, thousands of new personnel have been employed, making Turkey the leader in the world after Russia in the number of police officers per 100,000 people (Reference KobalKobal 2014).Footnote 12 Then a new law was passed in 2015, granting immunity to police officers when they respond to popular demonstrations.Footnote 13 As a result, police forces have become more aggressive and faced no consequences for using violent methods vis-à-vis civilians, as demonstrated by the acquittal of all police officers who were charged with using disproportionate violence against protestors during the Gezi Park uprising in 2013. Equally significant are the incentives given to police officers to detain and bring to justice ever-more numbers of people. Even though this has put enormous pressure on the legal system by massively increasing the caseload of judges, the government has so far not backed down from this punitive approach. Between 2001 and 2009, the average time for a case to be processed has increased from 138 to 399 days despite the fact that close to 2000 new judges and prosecutors have been appointed in the same period (see Table 3). With nearly half of the new cases brought to Turkish criminal courts being postponed to the following year, case overload continues to haunt the Turkish legal system (see Table 4).

Table 3. The Average Waiting Time for a Judicial Case in Turkey (Day) (2001–2009)Footnote *

* Note: Turkish Statistical Institute has provided the data on the average time for a judicial case only until 2009.

Source. Turkish Statistical Institute (TURKSTAT), 2016.

Table 4. Cases at the Criminal Courts in Turkey (2013)

Source. Turkish Statistical Institute (TURKSTAT), 2016.

The overcrowding of prisons and the slowdown in the delivery of justice necessitate some radical intervention to release pressure from the system. In the past, declaring a general amnesty proved to be the most reliable and politically safe intervention, used by many governments. The AKP government, on the other hand, has refused to pass an amnesty and attempted to resolve these problems by certain tools and managerial interventions from within the system, which we discuss below. Such a policy change has helped the government to move away from an image of the state as too lenient and incapable of dealing with problems without recourse to extraordinary measures like amnesty.

ii) Individual Responsibilization

One of the pillars of a neoliberal penal regime, as we argued, is the discursive construction of social actors who act purely on the basis of rational expectations—i.e., maximization of gain. As such, criminal behavior is seen as a pure individual choice that precludes social structural reasons and circumstances (Reference GarlandGarland 2001). Holding individuals ultimately responsible also has important implications for the rehabilitation stage of punishment. From such a perspective, the most efficient punishment is one that motivates offenders to internalize the negative and positive incentives and consequences for their actions during their sentence term, which would lead them to modify their behavior on their own to avoid negative sanctions and earn positive rewards (Reference Morgan, Duff, Marshall, Dobash and DobashMorgan 1994: 135–7).

The clearest expression of this responsibilization motive can be found in the institutions of parole and probation, which act as powerful tools of reforming the behavior of convicted offenders without using open coercion (Reference LynchLynch 2000: 40). Through parole/probation, individuals are expected to reform their own conduct by responding to positive incentives (continuation of the probation), and negative sanctions (possibility of imprisonment). As such, they are a more efficient and less costly form of punishment compared to imprisonment. Moreover, parole/probation also relieves the system of its excess capacity without recourse to extraordinary measures such as general amnesty. Probation/parole, then, plays a double role in the making of a neoliberal penal regime by both creating the kind of subject who is responsible for his/her own behavioral reform and creating the conditions for the sustainability of the system without moving away from a punitive “no tolerance” approach to crime.

Conditional releasing of convicted offenders became a part of the Turkish criminal justice system in 2004 with the enactment of the Law Regarding the Execution of Prison Sentences and Security Measures. In 2013, Turkey also introduced electronic surveillance to control prisoners on probation effectively. Convicted offenders who have one year left in their sentence are eligible for automatic release under probation, given they have displayed “good conduct” during their term in prison. However, they can apply for probation a year before their actual probation eligibility. If their application is accepted, they can be released two years before their actual prison sentence. Furthermore, convicted offenders who have received a sentence of 18 months or less become eligible for probation without serving any time in prison (Reference MandıracıMandıracı 2015: 30). Probation, then, has become a compulsory mechanism for all crimes sentenced to a maximum of 18-month imprisonment. Between 2005 and 2016, around two million prisoners have been released on probation and around 15,000 of them are under electronic surveillance.Footnote 14 As Table 5 shows, the number of probation decisions has dramatically increased throughout the AKP era (see Table 5).

Table 5. Number of Probation Decisions (2006–2015)Footnote *

* Source. Turkish Ministry of Justice, Department of Probation, 2016.

The probation system has proven beneficial to the Turkish government at least on two grounds. First, it has allowed the government to tackle the problem of overcrowding in prisons with a cost effective and politically acceptable method, as evidenced by the lack of any strong opposition to its use among the public so far. Despite their ideological and political differences, almost all our interviewees supported the introduction and increasing use of probation as a correction method. They also argued that probation has helped the government in managing the criminal justice system without an amnesty. Through probation, AKP has successfully managed to avoid the potential conflict between its “zero tolerance” policy towards crime and the consequent rise in the prison population. A good example of how probation has helped AKP is the aftermath of the failed coup attempt in July 2016, which resulted in the arrest and sentencing of thousands allegedly involved in the coup. Given the lack of enough room in prisons for these people, AKP announced a plan to conditionally release 38,000 people from prisons, which has not yet been completed.Footnote 15 To rumors that AKP will pass a general amnesty to empty out prisons, the Minister of Justice has responded that “an amnesty is absolutely out of question.”Footnote 16

The effective and strategic use of probation has also played an important role in fulfilling EU norms and regulations on punishment. The European Council has, since the late 1990s, issued multiple memoranda on the need to resolve the problem of overcrowded prisons in a humane way and probation has always been its top policy choice in this regard.Footnote 17 In this regards, the institutionalization of probation had been an EU-led penal reform in Turkey. However, EU's demands are not the only reason for the introduction of probation in Turkey. An equally important reason is overcrowding in prisons. With the upsurge in incarceration rates, the prison system stands on the edge of a deadlock with no room available for new inmates. Probation helps the government to relieve overcrowded prisons without recourse to amnesty. As Reference ÖzkazançÖzkazanç (2011) argues, the neoliberal penal system that AKP has constructed brings together two seemingly contradictory factors together—i.e., mass incarceration and the development of alternative mechanisms to imprisonment such as probation. Even though a less harsh punishment than imprisonment, probation still expands the penal net and contributes to the massive increase in the numbers of people entering the system.

Although the most significant, probation is not the only novelty that AKP has brought to the Turkish legal system to make it simultaneously more cost-efficient and facilitative of self-responsibilization. Two other mechanisms to this end are the creation of ombudsmanship in 2012 and mediation courts in 2013. The former aims at resolving disputes between individuals and state institutions (Reference Efe and DemirciEfe and Demirci 2013) and the latter between individuals before they escalate to become actual (criminal or other) lawsuits that would add further pressure on the already clogged legal system (MoJ 2012). Between 2013 and 2016, around 20,000 individuals have used the ombudsman services (MoJ 2015: 48) and another 3,386 cases have been settled through the mediation mechanism (MoJ 2016b). As well as acting as buffers against overloading of cases, these two mechanisms also demand from citizens their active participation in the legal system to resolve disputes in an efficient, cost-effective and rapid manner. In other words, they act as tools of self-responsibilization that are expected to raise the legal consciousness of individuals.

iii) Managerial Rationalization

Any penal system that undergoes a major upsurge in the level of punitiveness must rationalize its managerial tasks and ranks in order to cope with the new status quo more effectively. New databases need to be formed to track and monitor those in the system; new policing strategies need to be implemented; new prison complexes need to be created as well as old ones being reformed; a more efficient communication and coordination between different institutions need to be ensured for information to flow efficiently and orders to be executed promptly; and the staff needs to be trained to become competent enough to work with the new rules, norms, and behavioral codes. These difficult transitions require major investment, political will and strength given the ‘stickiness’ of institutions in times of rapid change.

The dire need for rationalizing the Turkish criminal justice system was apparent before AKP's punitive turn. As one of our interviewees from The Association for Freedom of Thought and Educational Rights, an Islamically oriented human rights association, has argued that the legal system in general and the criminal justice system in particular had been the most serious shortcoming of the period before AKP came to power.Footnote 18 The delivery of justice had been notoriously slow in the country in all domains of law, including criminal law. Prisons continuously experienced chronic overcrowding problems. The use of physical and psychological violence and torture against convicted inmates and detained individuals had become ordinary practice among law enforcement agencies and prison guards. Last, but not least, the system had become so corrupt that when a traffic accident in 1996 revealed that the Deputy Police Chief of Istanbul, a Kurdish MP who led a large paramilitary force against the Kurdish guerrillas, and a contract killer on Interpol's red list were travelling in the same car with several long-range weapons in the trunk, the state's reaction was to rapidly close the case with only minor prosecutions and sentences.

When AKP took office, in other words, the challenge it faced was substantial. One of the first steps that the new administration took was to pass the aforementioned new penal code in 2004. Strikingly, the old penal code in Turkey dated back to 1926 when the founders of the new Republic adopted Italy's penal code for the country. Despite being reformed 62 times since then Turkey's old penal code retained the spirit of the original 1926 law that sanctified the state above all else. This old penal code also was highly inaccessible for not only lay persons but also even for legal professionals due to its archaic language and its complicated format (Reference ErdoğanErdoğan 2005: 7). The new penal code greatly simplified the language and the format of the text so as to make it much more accessible for people. It is also much shorter than the old one. Furthermore, it put more emphasis on crimes against individuals compared to the old criminal laws, which can be evidenced by their prioritization in the text (Reference YeniseyYenisey 2012: 123). The definition of crimes against individuals and the subsequent sentence each crime deserves have also been reformed to make them more rational. As one of the lawyers we interviewed explains, “unlike old laws that used to sanctify the state, this new Penal Code puts the ‘individual’ first by redefining the appropriate sentences for crimes against individuals.”Footnote 19 In addition, the new law also defined new types of offenses and lengthened the minimum sentences for crimes to more effectively deal with the crime problem as we discussed above.

The second step in rationalizing the system was the creation of a national judicial information network (UYAP) in order to integrate all data under a single database, thereby speeding up legal processes and improving coordination between different institutions. Even though the decision to create such a database had been taken in 1998, before AKP came to power, it was under the AKP administration that the most substantial parts of the initiative were completed. With UYAP, legal personnel based in different institutions and offices are able to share information instantaneously, which has been highly effective in preventing delays in the procession of cases. Given the excess caseload of Turkish courts, UYAP has been a crucial tool in managing such a system as well as in economizing on expenditures caused by transaction costs. This information network has also made the delivery of justice more transparent and less prone to corruption. Because citizens and lawyers are also allowed to access digitalized documents regarding their own cases, they can effectively monitor how their cases are being processed and object to any irregularities.

The pooling of data has also enabled the institutionalization of new performance criteria by which the success/failure of the legal system can be measured. As Reference GarlandGarland (2001:120) argues, criminal justice organizations under neoliberalism have become more self-contained and inwardly oriented and, consequently, less committed to externally defined social goals or purposes. This reveals itself most clearly in the new way in which organizations measure their performance—i.e., not through their substantive transformative capacity but according to their success in meeting a series of “objective” management targets such as the ability of processing the maximum number of cases (Reference BellBell 2011: 84). Similarly, in Turkey the performance of penal institutions began to be measured through such a managerial logic based on the efficiency in the internal operations of the system. Since 2006, the MoJ has been preparing annual activity reports and since 2010, it has been putting out five-year strategic plans to enhance the level of efficiency of legal institutions. In other words, quantifiable objectives in the procession of cases, which include arrest and incarceration rates as well as number of projects and investments to be completed, have become the new indicators of performance. Not surprisingly, this new organizational culture has contributed to the expansion of the criminal justice system by incentivizing more arrests on the part of the police, more aggressive charges on the part of public prosecutors, and more conviction decisions on the part of judges. For example, when asked his opinion on rapidly expanding incarceration rates, the Minister of Justice claimed that “increasing prisoner numbers are an indication that our government is effectively fighting crime and criminals. With new technologies, new legal reforms, higher numbers of judges and courts, we are able to catch criminals, hold them responsible and quickly process their cases.”Footnote 20

AKP's main policy response to the twin problems of prison overcrowding and caseload in courts has been the quantitative expansion of the facilities and their personnel. According to the MoJ's 2015–2019 Strategic Plan (MoJ 2014: 45), the number of judges and prosecutors increased from 10,529 to 14,801 between 2010 and 2015, a 41 percent increase. There has also been a 64 percent increase in the total number of personnel employed in criminal justice institutions (ibid: 50). The same report states that between 2003 and 2014 there has been a nearly six-fold increase in courtroom space from approximately 570,000 to more than five million square meters (ibid: 46). Three new court complexes built in in Istanbul house 750 courtrooms, half of which are criminal courts. The increase in the number and capacity of prisons has also been impressive. Between 2006 and 2016, 105 new prisons have been built and 34 existing prison complexes have been expanded, together increasing the total capacity of the prison system from 80 to a little over 180,000 people (MoJ 2016a). People employed in prisons also rose from 30,000 in 2010 to nearly 50,000 in 2015.

A final move in the way of creating a more rational, standardized and efficient system is the initiation of in-service training programs for judicial personnel through the Justice Academy, created in 2003, and the Education Centre for Prison Personnel, founded the following year. The rigorous training given to judges, prosecutors, police officers, and prison guards has contributed to the internalization of a new organizational culture and behavioral norms by the personnel to not only increase efficiency but also decrease the high levels of rights violations that take place inside Turkish prisons. The installation of security cameras inside prisons has also helped in this task as cameras also monitor the behavior of prison staff towards the inmates. Prisoners are now given the right to write petitions to the prison management if they believe they are mistreated and the management takes these petitions seriously. The high number of prison personnel who are called by public prosecutors to respond to complaints by prisoners is partial evidence that the new organization culture is already delivering some results.Footnote 21

To sum up, AKP's reforms of the criminal justice system have simultaneously caused a substantial increase in the numbers of convicted criminals, created the mechanisms and institutions to control such large numbers without having to recourse to extraordinary measures, such as general amnesty. Even though such neoliberal reform tendencies began before AKP took office, their scale and scope were quite narrow and systemic mechanisms to deal with the consequences of a more substantial neoliberal transformation were largely missing. As such, AKP brought about a quantitative as well as a qualitative transformation in Turkey's criminal justice system. And these transformations began before AKP steered away from its democratization and EU membership agenda, and adopted highly authoritarian governance policies and repressive tools after 2009. In the rest of the article, we delve into the ideological and political motivations behind these transformations, which have largely ruled out amnesty as a policy choice. We argue that the party's neopopulist ideology, which is founded upon an image of a strong, capable and retributive state that is able to effectively deal with crime without recourse to extraordinary measures, is both cause for and consequence of its new penal policies. The image of a strong and authoritarian state relies on the state's ability to address crime and criminals in an effective way; hence the punitive turn. But state strength also depends on effectively managing increased numbers in the criminal justice system without losing control; hence managerial solutions and the refusal to pass general amnesty.

Legitimacy, Amnesty Politics and AKP's New Populism

Why do states forgive convicted criminals, and what kinds of crimes do they forgive? The answers to these simple questions, we argue, get to the very heart of state-making processes as well as state–society relations. The right pardon individuals and/or groups gives to states enormous power to increase their legitimacy among certain constituencies, thereby securing their allegiance to the state. Conversely, during times of intense internal conflict and strife, states that are unable to pacify opponents might be forced to grant amnesty to those convicted from the opponent group in order to reach some kind of peace and stability. Forgiving criminals can also serve as a vital mechanism of providing societal peace during times of regime change and/or new state formation. During such moments, it becomes logistically and ideologically impossible for the new regime to convict large numbers of people with allegiance to the previous regime, thus leading to some form of amnesty and reconciliation that makes co-existence possible. A final utility that the right to pardon provides to states is managing the problems of an overburdened criminal justice system, particularly under conditions of resource deprivation. For states that cannot handle overcrowded prisons and heavy caseloads, amnesties of various kinds prove handy as they offer a temporary relief for the system.

The decision to pardon or punish offenders, then, is intimately related to how a government seeks legitimacy. As such, pardoning is a morally and politically laden action motivated by conflicting values and expectations. On one side are the offenders and their families who rely on the goodwill and mercy of a government that might choose to release them because of political calculations, internal/international pressure or ethical/moral choices. On the opposite side are those victims and their families who pressure political authorities not to pardon offenders. The consequences of large-scale amnesties on public opinion add further complexity to the act given the politically sensitive character of pardoning offenders and the likelihood of politicians to exploit the public's sensitives. The opinions and pressure of legal professionals, experts and civil-society organizations for or against pardoning offenders can also shape the terms of the debate around amnesty as well as its outcome. Finally, there are the functional requirements of a criminal justice system that need to be well managed to avoid collapse. Therefore, the decision to pardon is never simple; it largely depends on balancing the morally ideal with the politically feasible. As one of our interviewees from Criminal Law Association has put it, “any amnesty policy must strike a balance between ideals and realities.”Footnote 22 Neither the former nor the latter are straightforward. Any decision is likely to cause tensions, conflicts, and fissures within society, and perhaps more important, between segments of society and the state. When the prevailing approach to amnesty fundamentally changes in a country, as it happened in Turkey under the AKP government, it provides an opportunity to explore how the moral ideals and political power balances as well as calculations are changing in that society. It is these transformations, we hold, that are central not only to amnesty politics but also to the neoliberalizing reforms we reviewed in the last section.

The act of amnesty, we argue, contains three underlying tensions, which are ideological, political and moral at heart. We argue that AKP's resolution of all three constitutes a sharp break in Turkish penal history and is indicative of a much larger shift in state-society relations and state legitimacy from a populist to a neopopulist mode. The first tension concerns the rationale for forgiving in the first place. Why should an offender, or group of offenders, be forgiven? What kind of a symbolic message this gives to other offenders and to the society? Would it amount to a weakness on the part of the forgiver or show, on the contrary, the morality and might of a powerful and forgiving authority figure? The second tension is about the coverage of an amnesty law. Who deserves (or needs) to be forgiven and why? Does a state forgive those it cannot suppress or silence? Does it forgive people for attaining and/or maintaining societal peace and reconciliation? Alternatively, does it pardon offenders when it can no longer institutionally contain them? The third, and final, tension regards the actor that has the moral and/or legal right and responsibility to pardon. In modern states, it is the state, as the ultimate sovereign body, that holds this right. However, in most premodern political entities, with complex/plural systems of (criminal) law that combined elements of religious, secular as well as customary jurisprudence, states shared the right to pardon with other persons or institutions, depending on the nature of the crime.

First Tension-Why Forgive?: Why should a state, or any other source of authority, pardon offenders? Before AKP came to power, two main rationales were at work in Turkey in motivating the state to declare amnesties: Functional requirements of the system, and an ideological and discursive construction of the state as a mighty father that forgives his unfortunate children who are pushed to crime for various reasons.Footnote 23 Since we have already discussed the first rationale in the previous section we now focus on the latter. The sovereign forgiving the crimes of his subjects or writing off their financial debt is a phenomenon widely observed throughout history (Reference GraeberGraeber 2011; Reference Hay, Linebaugh, Rule, Thompson and WinslowHay et al. 1975; Reference MooreMoore 1997). By such an act of mercy, the sovereign not only displays his morality and might, but also solidifies his legitimacy among the public. This is evident in the kinds of discourse mobilized in modern Turkey when amnesties were passed. For example, the person largely held responsible for the passing of the last amnesty law in 1999,Footnote 24 Rahsan Ecevit, who was the wife of the then-serving prime minister from the center-left DSP, has stated, “Even when God forgives, wouldn't it be right for states to also forgive sometimes?”Footnote 25 Drawing parallels between the state and divine authority, she suggests that states have a moral duty to forgive. When criticized that a general amnesty might benefit those criminals who should never be forgiven, she adds:

I do not want an amnesty for terrorists, ferocious murderers, those swindling the state or rapists! I want it for those pushed to crime by poverty, hunger and excessive unfairness in the social order, for those who commit crime unintentionally.26Footnote 26

Here the discursive justification of an amnesty is laid bare. The state should forgive its unfortunate citizens who are victims of an unjust order. The Turkish phrase that captures such a line of thinking is kader kurbanları, or victims of fate, which has a powerful and central place in how people make sense of the unequal world they experience. By mobilizing such a discourse, state actors tacitly accept the idea that criminal responsibility cannot be entirely attributed to individuals. Rather, inequalities and unjust living conditions push people towards criminal behaviour.Footnote 27 That it was a left-leaning party (DSP) that pushed for the 1999 amnesty is also understandable as left-wing parties and politicians are more likely to put emphasis on structural inequalities and individual victimization.

Even though the 1999 amnesty mobilized a popular discursive element, its timing was very much miscalculated. By the late 1990s, the Turkish public was demanding a much more heavy-handed and tough approach to providing law and order that precluded such a legitimizing move around the “victims of fate” discourse. After enduring years of political instability, successive economic crises, widening inequality, and a prolonged civil conflict that claimed more than 30,000 lives and uprooted millions, the public was ready to embrace more authoritarian policies of dealing with crime and criminals. Furthermore, several waves of “moral panic” around street crime (Reference Hall, Critcher, Jefferson, Clarke and RobertsHall et al. 1978) had swept large cities and further agitated the public, not least due to sensational and largely exaggerated media coverage of ordinary crime. Therefore, when the 1999 amnesty was passed, the Turkish public very negatively received it.Footnote 28 Sensational media reports linking the supposed increase in street crime with people released as part of the 1999 amnesty, without any solid evidence, only added fuel to the fire.Footnote 29 Even Mrs. Ecevit, the mastermind behind the amnesty act, accepted these criticisms and publically stated that she “wanted the amnesty for poor folks, but murderers benefited in the end” (General Directorate of the Democratic Left Party [DLP] 2002).

AKP came to power in 2002 in such an environment by capitalizing on the insecurities, fears, and anxieties of the masses who had just gone through a major economic crisis in 2001. As we have discussed above, the new administration significantly widened the penal net and adopted a zero-tolerance approach to crime. An important aspect of this new approach is rejecting a general amnesty that would release offenders. These are constitutive parts of the party's new populism that is constructed on the image of a strong and capable state that delivers goods and services to the public without having to recourse to extraordinary economic and/or legal measures like past governments. A general amnesty is, by definition, such an extraordinary measure. By demonstrating to the public that it can manage things without an amnesty, AKP gives the symbolic message that the state is strong and in control. Compared to the past justification of amnesties around certain normative discourses, this new approach is a radical change based on a completely different representation of the state that holds individuals ultimately responsible for their criminal acts, thereby satisfying the demands of the larger public for law, order and retribution.

Second Tension-What to Forgive?: While rejecting an amnesty to ordinary criminals, the AKP government has opened the door, for the first time in Turkey, to explicitly use amnesty for political purposes by pardoning political criminals who committed crimes against the state. Since the government has not issued amnesty for political crimes yet, we should note that the AKP's approach to political amnesty remains at a discursive level. While past governments deliberately kept political prisoners out of any general amnesty, leaders of the AKP have repeatedly argued that a state can only forgive crimes committed against itself and has no business in pardoning those who have violated other people's rights. The difference in approach could not have been starker when we compare the words of Mrs. Ecevit above, where she proudly declares that the 1999 general amnesty excludes “terrorists…and those swindling the state,” with Mr. Erdogan's words, the uncontested leader of AKP: “I have a different idea on amnesty. Only the victims have the right to forgive the crimes against themselves. The state has the right to grant amnesty only for crimes against itself.”Footnote 30 This reversal of policy on who the state can forgive does not only signal a “normalization” of amnesty politics in Turkey by bringing amnesty policy closer to the norm around the world; it also has paved the ground for the possibility of granting amnesty to thousands of Kurdish political prisoners serving long sentences on terrorism charges. If there ever will be a peace settlement between the Turkish state and the Kurdish insurgency movement, the issue of political prisoners will have to be settled on mutually acceptable terms, which will entail some form of amnesty for the prisoners. Had the peace process that the AKP government formally started with the PKK in 2013 not come to a sudden and bitter end in the summer of 2015, we probably would have witnessed the realization of this possibility. However, as we discuss in the conclusion, a political amnesty might after all be inevitable especially after the massive surge following the failed coup in the summer of 2016.

Third Tension-Who Can Forgive?: On the question of who has the legitimate right to pardon, AKP has once again radically departed from past practice. The party leaders have claimed that only the victim of the crime, or the victim's families and inheritors can forgive crimes committed by one individual against another. This view has strong roots in Ottoman law, which was strongly shaped by the Islamic shari'a, where the Sultan could only pardon crimes committed against his authority (like banditry, espionage, or army-desertion) but did not hold the right to pardon anyone who commit crimes against the community (such as fornication or theft), and, more importantly, crimes against individuals including murder, wounding and insult (Reference EkinciEkinci 2008). As Reference GörkemGörkem (2014) argues, the victim or the victim's family could only forgive these crimes.Footnote 31 At the basis of this understanding lies the Islamic concept of kul hakkı, which can roughly be translated as “the rightful share of a believer,” which lies beyond the domain of the political. The following words of Mr. Erdogan capture the essence of such an understanding:

I have no right, as the Prime Minister, to forgive a murderer. I have never accepted the state's authority of granting amnesty for a murderer. Why not? Because the right to forgive that murderer belongs only to the inheritors of those murdered, not to the state. Only for crimes against the state, such an amnesty decision can be made. Otherwise, if I forgave a murderer within the scope of general amnesty, how would I give an account of this to the victim and their families? There is no way such a thing is going to happen.Footnote 32

That the PM believes he cannot “give an account of” forgiving the criminal to the victim's family signifies the moral basis of the relationship between the state and citizens. If the state forgave a crime committed against an individual, it would essentially be violating the fundamental rights of this person bestowed upon him/her by God. This suggests that the tenets of Islamic law is a contributing factor as to why the AKP government rejects an amnesty targeting crimes against individuals while approving pardoning only crimes against itself—i.e., crimes against the state.

Even though Islamic law is not part of the legal system in Turkey, as result of the adoption of a secular constitution and the outlawing of shari'a law, there has recently been a growing and mostly informal interest in implementing some aspects of Shari'a, particularly after AKP came to power (Reference Turner, Arslan, Possamai, Richardson and TurnerTurner and Arslan 2015). This has caused increasing tensions among those state actors who see the protection of the secular state apparatus as their primary goal and the religious conservative groups who want to introduce religious doctrines into official law. The way AKP ideologically legitimizes its anti-amnesty policy and various objections to this legitimization constitute one such tension between the secular establishment and the desire, on the part of some, to codify religious law as official law. Given that the secular Turkish constitution gives the right to grant amnesty/pardon only to the state and not to individuals, this controversy is, in a sense, not surprising. As a reaction to Erdogan's statement, the then-vice president of the main opposition party (CHP) stated that his view is fundamentally incompatible with the secular principles and with the idea of a modern state where laws are based on the constitution, not on religion.Footnote 33 Similarly, the deputy president of another opposition party (MHP) criticized Erdogan's views by arguing that amnesty is a profane issue that should not be discussed in the framework of divine rules. Our interviewees from two left-leaning lawyers’ associations also strongly criticized AKP's stance on kul hakkı and amnesty for their religious foundations.Footnote 34 Those who came to the PM's defense, however, formed their discourse mostly around the legitimacy of religious rules. For example, an AKP member of parliament stated, “How can we forgive a criminal by putting ourselves in the place of the victim even when God refuses to intervene with kul hakkı. If I am victimized, I must be the one who forgives, and no one else must have that right.”Footnote 35 Another defense came from a lawyer who was a member of a pro-government lawyers’ organization, the Platform for the Supremacy of Law (Hukukun Üstünlüğü Platformu).Footnote 36 When we asked him if it is right for aspects of a country's (criminal) law to be based on customs and traditions, he replied, “What else can be more natural than the implementation of legal rules arranged by religion to live in peace and security?”Footnote 37 Another lawyer from The Association for Freedom of Thought and Educational Rights (Ozgur-Der) also claimed that “For those who know Islamic theory and law and who have not surrendered their minds to other views, the argument that the state can only pardon crimes against itself, and no other, is only normal.”

When we think of AKP's resolution of all three tensions together, we get a clear sense of the core logic and constitutive principles of the party's neopopulism—i.e., a strong retributive state that protects victims’ rights over offenders and that is capable of dealing with structural problems without extraordinary measures. This populism lies at the heart of the neoliberal reforms we discussed above. The refusal to pass a general amnesty makes perfect sense in the larger context of the party's ideological and political commitments and its institutional reforms that we reviewed in the previous section. A strong anti-amnesty stance fortifies the party's zero-tolerance penal approach and confirms its commitment to fixing institutional problems through managerial rationalization. Moreover, it strengthens the image of a powerful and capable state that is able to deliver (i.e., provide law/order) without losing control (i.e., granting amnesty). The refusal of the party to forgive any crimes other than those committed against the state also goes hand in hand with an individualized view of crime and criminals that holds the offender ultimately responsible for his/her actions. Finally, the religiously motivated view formed around the concept of kul hakkı shares many elements with the “victim-centered” views of justice that are becoming more prevalent around the world (Reference Strang and ShermanStrang and Sherman 2003). Even though victim participation has not yet become an integral part of the Turkish criminal justice system, it was officially announced as an important target of the prospective Legal Reform Bill in 2015. The denial of amnesty to convicted criminals relies on a neo-populist rhetoric that claims to defend victims’ rights rather than prioritizing the rights of offenders.

Conclusion

Amnesty has always been a highly politicized and sensitive issue, intimately connected to state legitimacy, political stability and institutional sustainability. As such, a thorough examination of its implementation in a given country has the potential to reveal crucial dynamics regarding state-making and state–society relations. In this article, we have focused on a puzzling case that has gone through a major transformation in the way amnesty is conceptualized and utilized. Whereas past governments in Turkey have relied on amnesty mostly as an “emergency button” to resolve chronic problems associated with the criminal justice system, the AKP government has significantly changed this policy and refused to pass any comprehensive amnesty to pardon convicted criminals. Even though the Turkish criminal justice system is acutely challenged with the same sort of problems that gave way to amnesties in the past, the government strongly refuses to rely on amnesty as a solution. That is why, the absence of general amnesty itself is a puzzling policy choice which deserves attention. What is more, AKP's approach to amnesty also opened up the possibility to issue an amnesty exclusively to political criminals who have usually been kept out of past amnesty implementations. Arguing that the state can only forgive crimes against itself and has no right to forgive crimes committed against citizens, AKP brought the amnesty field, at least at a discursive level, closer with the rest of the world where general amnesties are utilized as a modality of pardoning political crimes to attain transitional justice and maintain internal peace and stability.

We argue that this shift in amnesty policy is part of a much larger transformation of the criminal justice field in Turkey towards what we called a “neoliberal” penal regime that (i) is more punitive in its dealing with crime and criminals, (ii) places the ultimate responsibility of individual offenders at the center of its penal mentality, and (iii) strives for a heightened degree of organizational rationalization and efficiency in dealing with the consequences of the first two. Through various reforms and new institutions, the AKP government formed the backbone of such a regime in Turkey between 2002 and 2009, a period characterized by wide-ranging democratization in the country supported by the EU. This neoliberal regime then served the party very well as it embarked on a relentless path of authoritarianism after 2009. We argue that the core logic of a neoliberal penal regime is fundamentally opposed to a wide-ranging amnesty that would not only signal leniency on the part of the state to deal with the problem of crime, but also violate the organizational promise of the system for enhanced efficiency and capability in managing problems. But, the massively increased numbers of people entering the criminal justice system as a result of these neoliberal reforms as well as the authoritarian crackdown on opposition since 2009 has created serious pressures on the system, which threaten its sustainability. Without the adequate financial, logistical and administrative resources, the AKP government is falling victim to its own penal regime. Herein lies, we argue, the paradox that many other developing countries face as they try to adopt increasingly punitive policies and measures without the necessary resources to implement them. As such, Turkey is an exemplary case to observe and study the tensions and contradictions that a populist and authoritarian developing country government faces as it embraces neoliberal penal policies for political as well as ideological reasons.

The most important driving force behind these neoliberalizing reforms, we contend, is AKP's Islamically-guided neopopulist ideology, constructed on an image of a strong and capable state that no longer relies on extraordinary measures in dealing with structural problems in various domains of social and political life. Passing an amnesty would go directly against such an image. This neopopulist ideology has also caused a major shift in the state's view of offenders compared with the past. Whereas the old populism of various political parties in Turkey constructed criminals as “victims of fate” who need a second chance in life (and hence the possibility of forgiveness), AKP's ideology holds criminals ultimately responsible for their immoral choices. Mobilizing the Islamic discourse of kul hakkı, AKP's new ideology unflinchingly places the victim at the heart of all debates and decisions. Therefore, a comprehensive amnesty would absolutely go against the new populist ideology of the party.