Introduction

There are long-standing concerns of inequalities in the workplace among minority ethnic (ME) and migrant workers within the British labour market. ME workers are over-represented in low paid sectors in general (Weekes-Bernard, Reference Weekes-Bernard2017) and under-represented in higher-paid occupations within sectors, including health and social care low-paid jobs (Skills for Care (SfC), 2020; Workforce Race Equality Standard (WRES), 2020). The health and social care workforce, particularly the latter, includes a significant proportion of workers paid on or below the national living wage (Hussein, Reference Hussein2017a; SfC, 2020), with insecure work contracts that force many to work considerably long hours to maintain regular incomes. Thus, many workers in low-paid health and social care jobs are vulnerable to unfavourable working conditions and adverse outcomes that are likely to be linked to the combined effects of race, gender and nationality and the structural and organisational factors related to these specific sectors.

Racism and discrimination at work lead to losses at the labour market level, such as deskilling and skill under-utilisation (Rafferty, 2020) and several adverse work and individual outcomes (Serafini etal., Reference Serafini, Coyer, Speights, Donovan, Guh, Washington and Ainsworth2020; Xu and Chopik, Reference Xu and Chopik2020). Such adverse influences span throughout the employment processes, from recruitment to working conditions and progression opportunities. There are also negative implications on the individual workers’ wellbeing, employment outcomes, and the quality of care provided (Birks etal., Reference Birks, Cant, Budden, Russell-Westhead, Özçetin and Tee2017; Etherington etal., Reference Etherington, Jeffery, Thomas, Brooks, Beel and Jones2018; Milner etal., Reference Milner, Baker, Jeraj and Butt2020). Understanding the barriers and constraints to health and social care racialised workers’ positive work outcomes is essential to design evidence-based policy recommendations and interventions to ensure equality in the workplace and beyond. This is particularly important within the context of growing demands due to demographic changes and population ageing that is coupled with an increasing reliance on women, migrants and workers from minority groups. The latter groups of workers are more likely to accept unfavourable working conditions due to the wider labour inequalities and stratifications reducing their access to certain jobs and sectors with better pay and working conditions.

This review article aims to provide evidence on the treatment, experiences, and outcomes of ethnic minority workers in health and social care in the UK, particularly on low-paid jobs within these sectors. Ethnicity is not fixed or easily measured, and it differs from, but overlaps with race, nationality, religion, and migration status (Arrighi, Reference Arrighi2001; Khattab and Hussein, Reference Khattab and Hussein2018). Other social markers and experiences might further identify a minority group such as white Muslim women, white traveller communities, or white European migrants (through language and accent). In the literature, minority ethnic/race usually provides a way to define groups that look different and/or have separate ancestral roots (Crenshaw, Reference Crenshaw1989; Acker, Reference Acker2012; Joseph, Reference Joseph2019). For this review, we have included various terms to identify self-defined ethnicity, migration status and other minority groups such as religious and traveller groups.

Analytical framework

To analyse the results of this review, I employ an intersectionality approach, where race interacts with other characteristics such as nationality, religion, gender, and other social markers to influence workers’ labour market opportunities negatively. Intersectionality is a term initially developed by Crenshaw (Reference Crenshaw1989) to reflect on black women’s experience in the workplace, highlighting the multiple axes of inequalities across race, gender, class and ethnicity. Within this definition, the impacts of racism, sexism, and classism are not distinct from each other but interact to produce various layers of disadvantages (Khattab and Hussein, Reference Khattab and Hussein2018). Furthermore, organisational studies highlight that such intersectionality occurs within specific sectors and locators’ contexts (Acker, Reference Acker2012); hence, it is essential to emphasise that low-paid workers, especially in social care, are generally subjected to adverse work and employment outcomes related to how care is funded, organised and delivered. Trends in the marketisation of care have led to increased levels of fragmentation, precarity and job insecurity in this sector of employment (Atkinson and Crozier, Reference Atkinson and Crozier2020). Here, the patterns of disadvantages are reflected within the constraints of such organisational context revealing nuanced differences in the specific experiences of racialised workers relative to the broader working conditions and outcomes.

Within the low paid sectors in general, recent studies (Haque etal., Reference Haque, Becares and Treloar2020; Warren and Lyonette, Reference Warren and Lyonette2020) indicate that women from racialised backgrounds are twice as likely to work in low-paid, insecure and high-risk jobs and classified as ‘key workers’. While earlier research suggests some shifts in the British identity belief and attitudes with a reduction in the importance of associating ‘whiteness’ in determining being ‘British’ (Tilley etal., Reference Tilley, Exley, Heath, Park, Curtice, Thomson, Bromley and Phillips2004), evidence highlights that racialised British individuals continue to suffer from discrimination and institutional racism in the employment sphere and beyond. The analysis thus considers both individual and macro factors, including the role of institutional and structural racism in explaining observed employment outcomes.

Methods

The analysis is based on a rapid review of evidence methodology to collate recent evidence specific to the above research questions. The review was informed by guidelines for the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (Moher etal., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009). A rapid review methodology aims to synthesis knowledge in a timely manner, where some components might be simplified or omitted due to the speed of the process. In this rapid review searches were limited to certain dates (since 2017) and publications in the English language only. The review did not include a formal assessment of the risk of bias or quality appraisal and was conducted by one researcher only.

Review aims and questions

The review aims to understand to what extent race or structural racism contributed to less desirable outcomes experienced by ethnic minority workers, and the impact COVID-19 had on this group of workers, with the following specific research questions:

-

1. Are there significant differences in the employment, recruitment, retention and promotion of minority ethnic workers compared with the White British group?

-

2. What is the evidence that minority ethnic workers experience differential treatment and discrimination compared to White British workers?

-

3. What are the explanatory factors of any observed differentials?

Search retrieval and analysis

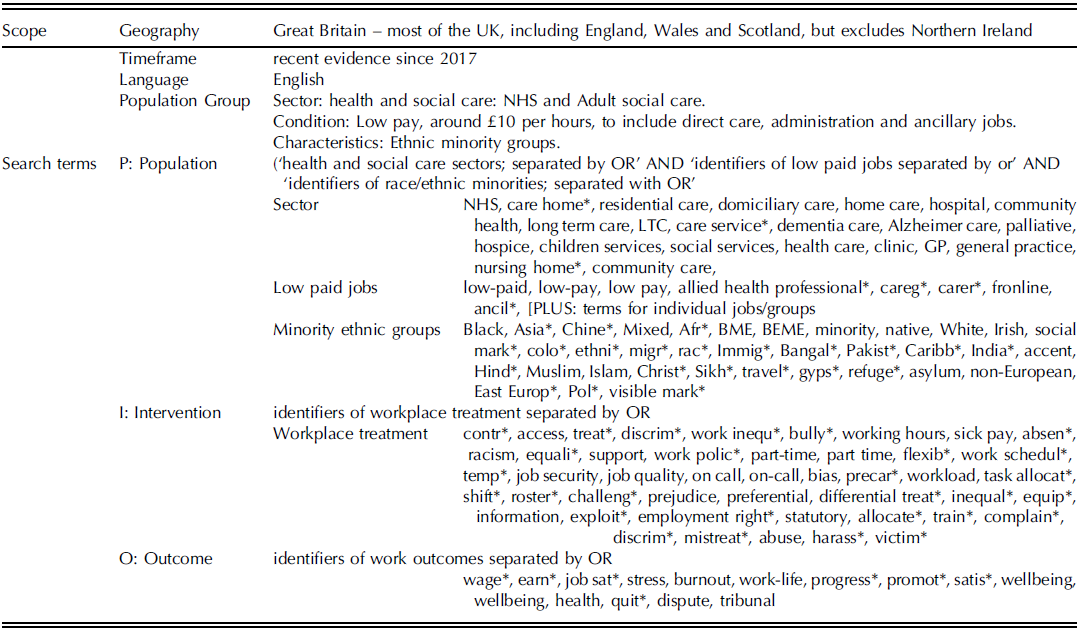

The review was funded by the Equality and Human Rights Commission and conducted in December 2020. We searched the following databases: Web of Knowledge, Nursing Index; CINAHL; EBSCO; ERIC; Social Care Online, SCIE, Google Scholar; NHS Evidence; Nursing@OVID; Medline; Pubmed and Scopus. The process started by defining different terms to identify search terms through an initial scoping of the literature. A search strategy protocol was then devised and discussed with key stakeholders and the funder. Table 1 presents a summary of the scope, coverage and search terms used in the review. The searchers focused on published research and restricted to recent evidence since 2017, with some exceptions that were made specific to seminal and critical work before that date. Publication titles and abstracts were assessed for relevance during the initial search phase before retrieving the publications’ full text.

Table 1 The review scope and search terms

Search results

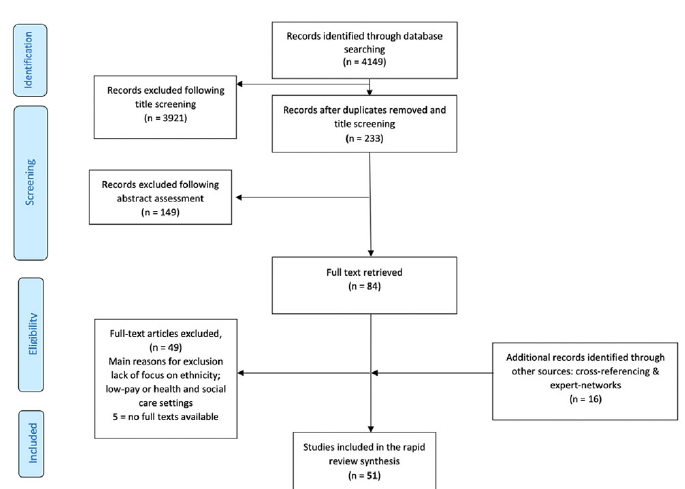

Over 4,000 publications were identified, and after the removal of duplicates and title screening, the abstracts of 233 records were assessed according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Following this assessment process, eighty-four records were eligible for full-text assessment, and the full text was retrieved. Based on the full-text assessments, thirty-five were judged to be relevant for inclusion. An additional sixteen records were identified through cross-referencing and a network of experts. In total, fifty-one records were included in this review (see Figure 1 for PRISMA flow diagram).

Figure 1 PRISMA flow-diagram of literature included in the review

The majority of included records were published in 2020 (n=19), followed by 2017 (n=12), with most records were peer-reviewed journal articles (n=31) or reports (n=17). Almost an equal number of publications reported research specific to the health sector (n=16) and adult social care (n=17), and two on public service professionals. Ten records had a broader focus on low-paid work and ethnicity, including, but not primarily, in the health and social care sectors. Finally, eight covered the experience since the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on ethnicity and the health and social care workers. In terms of methods, fifteen outputs reported on studies based on quantitative analysis of existing workforce data or household surveys; eleven employed qualitative techniques with a small number of participants (less than thirty) and eight with larger groups of participants (more than thirty); Seven publications were based on surveys; five were reviews; three employed experimental designs and the last three were commentaries or based on policy analysis.

Limitations of the review

The review was primarily focused on ethnic minority workers and hence studies considering the impact of other characteristics - such as religious affiliation, disability, or sexuality- were only identified if they also included a focus on race or ethnicity. Furthermore, most of the publications included in this review adapted either cross-sectional quantitative design or qualitative interviews with a small number of participants. This type of research allows the identification of correlations and associations between different factors and outcomes, rather than demonstrating causation.

Findings

Recruitment

The literature provides ample evidence on preferences for recruits from white ethnicities and those without visible markers, especially in the health sector. For example, Kline etal. (Reference Kline, Naqvi, Razaq and Wilhelm2017), examining national recruitment data to the National Health Sector, conclude that white applicants were 1.57 more likely to be appointed from shortlisting when compared to applicants from ME backgrounds with the same levels of qualifications and skills. Heath and Di Stasio (Reference Heath and Di Stasio2019) employed an experimental design and sent 3,200 fictional online job applications for advertised jobs in the UK’s health and social care sectors. This study showed applications profiling ME candidates to receive unfavourable responses significantly more than similar applications profiling white British candidates. In addition, they showed the most adversely impacted applications portraying individuals with visible social markers, e.g. with Muslim names or those linked to specific cultures.

The reasons behind such differentials are linked directly to the perceived characteristics of different racialised groups of workers by the employers and systems through institutional and structural racism and individual-specific factors. Institutional racism is defined as the collective institutional failure to treat people fairly because of their colour, culture, or ethnic origin. This can be observed in processes, attitudes, and behaviours that amount to discrimination through unwitting prejudice, ignorance, thoughtlessness, and racist stereotyping, disadvantaging racialised and minority groups (Lea, Reference Lea2000). Structural racism normalises historical, societal and institutional practices that disadvantage people with different characteristics, including racialised workers.

These widespread perceptions appear to be internalised by individual workers from minority groups themselves. Hammond etal. (Reference Hammond, Marshall-Lucette, Davies, Ross and Harris2017) suggest that newly qualified graduate nurses with minority backgrounds actively conform to specific images and make conscious efforts to accommodate existing biases throughout the recruitment process compared to other students by carefully analysing how they present themselves and how they interact with potential employers—making seeking employment among racialised groups more exhausting and complex as individuals aim not only to prove their clinical abilities but also to provide evidence to counter perceived opinion related to their identities, race and other characteristics. Such processes become more elaborate when more than one perceived, less favourable dimension is presented. For example, in the case of male Asian nurses, Qureshi etal. (Reference Qureshi, Ali and Randhawa2020) highlight the negative influences of the interplay between ethnicity and gender and how these influenced how this particular group of recruits needed to counter pre-perceived biases surrounding specific ‘qualities’ associated with being a good nurse with adverse implications on the recruitment and work experiences of male ME nurses.

Butt etal. (Reference Butt, Salmon, Mulamehic, Hixon, Moodambail and Gupta2019) focused on the process of recruiting healthcare professionals with asylum-seeking experiences. Their analysis concludes that while many such professionals manage to secure employment with support from various programmes, their skills are usually underutilised with downward labour mobility. The authors identify several individual-related, rather than systemic, challenges such as lack of knowledge and information, including those related to language and culture, as well as psychological trauma associated with their migration pathways. In addition, they highlighted that many participants found differences in the learning process, such as a greater emphasis on multi-disciplinary interactions and the use of idioms and cynicism within a learning or a professional context challenging to navigate.

In social care, Figgett (Reference Figgett2017) identifies the most common recruitment route to this sector through employee referrals and word of mouth, excluding certain groups of workers. In this context, employment agencies were vital for recruiting migrant workers to live-in and home care roles (Farris, Reference Farris2020). These findings resonate with the experience of the broader minority populations of relying on recruitment agencies when seeking employment as many lack the social networks that facilitate recommendations by peers. For example, Kerr (Reference Kerr2018), employing an extensive survey of 6,506 employees, finds that nearly 60 per cent of minority workers register with employment agencies compared to 46 per cent White British participants. Migrant workers were also over-represented in low paid jobs in different industries, including social care and are often recruited through agencies or gangmasters with an associated prevalence of weaker contracts and increased risk of labour exploitation (Barnard etal., Reference Barnard, Ludlow and Butlin2018; Farris, Reference Farris2020). Earlier research by Hussein etal. (Reference Hussein, Manthorpe and Ismail2014) shows that employers in social care reported recruiting significantly higher proportions of minority workers through employment agencies. These variations in the reliance on recruitment agencies among minority and migrant individuals are linked to weak social capital and poor labour market connections and reflect the wider disadvantaged position of racialised individuals within the societal structure (Figgett, Reference Figgett2017; Hussein and Christensen, Reference Hussein and Christensen2017; Howells etal., Reference Howells, Bowera and Hassell2018; Sahraoui, Reference Sahraoui2019).

The intersectionality of gender with ethnicity was explicitly evident in health and social care work, widely perceived as ‘good jobs for women', thus shaping roles and patterns of employments (Howells etal., Reference Howells, Bowera and Hassell2018). Such perceptions may facilitate the acceptance of trade-offs between flexibility and career progression opportunities among certain groups of workers, including ME, women and migrant workers (Howells etal., Reference Howells, Bowera and Hassell2018; Sahraoui, Reference Sahraoui2019; Farris, Reference Farris2020). Focusing on migrant men in social care, Hussein and Christensen (Reference Hussein and Christensen2017) highlight the role of the marketisation and the introductions of personal budgets in the care sector in creating ‘niche’ markets for employing migrant and ME male care workers. They argue that while such ‘niches’ in the labour market create opportunities for migrant male workers. However, such opportunities simultaneously pose several risks, including labour exploitation, under-employment and deskilling, among others.

Understanding how choices are affected by various well-held perceptions and views, through structural and systematic mechanisms, might help to explain the high prevalence of self-employment observed among ME workers (Hussein and Christensen, Reference Hussein and Christensen2017; Howells etal., Reference Howells, Bowera and Hassell2018). Here, existing systematic cultural biases within employers and organisations act as drivers for specific employment choices initiated by the individuals to avoid discrimination and enhance their occupational mobility (Howells etal., Reference Howells, Bowera and Hassell2018). Furthermore, financial pressures and remittances to home countries are considered critical explanatory factors in the decision of migrant workers to accept low-paid jobs even when they hold higher qualifications (Sahraoui, Reference Sahraoui2019).

Pay, reward and progression

Across pay groups and occupations within health and social care, women and ME workers follow employment patterns directly linked to gendered/ethnic division of labour (Howells etal., Reference Howells, Bowera and Hassell2018). In the NHS, ME staff are more concentrated in support roles and Middle Bands while significantly less represented in senior positions (Kline etal., Reference Kline, Naqvi, Razaq and Wilhelm2017). A systematic review by Bimpong etal. (Reference Bimpong, Khan, Slight, Tolley and Slight2020) identifies existing ethnic pay gaps among NHS doctors across the UK. Workers with black ethnicities were the least paid among support workers and midwives, while male health professionals held the most prestigious and highest compensated jobs in the NHS (Milner etal., Reference Milner, Baker, Jeraj and Butt2020). Furthermore, the gender pay gap in NHS England varies by ethnicity, with the direction usually favours men for most ethnic groups. Women from Asian ethnicities experience the most significant gender pay gap, followed by mixed-race and women of any other ethnic background. However, the gender pay gap only favours women when considering workers from black ethnic backgrounds, concluding that black men are the least paid in the NHS (Appleby, Reference Appleby2018).

The literature points to, and assumes, a ‘vocational’ nature for care work, with jobs being perceived and accepted as low-paid, low status and unqualified (Hussein, Reference Hussein2018; Farris, Reference Farris2020). Recent workforce statistics show that even within a generally low-paying sector, ME workers are still over-represented in lower-paid roles such as frontline direct care jobs and under-represented in supervisory and managerial positions (SfC, 2020). Research highlights that despite men being more likely to occupy managerial and supervisory roles in social care, ME men are significantly less likely than their White counterparts to be employed in these roles (Hussein etal., Reference Hussein, Ismail and Manthorpe2016).

Harassment and bullying in the workplace

Harassment and bullying in the workplace can take various forms and can be perpetrated by colleagues, managers, service users, patients, or the public. These actions can be overt or covert and manifest in prejudice and discriminatory behaviour, unconscious bias and microaggression, or verbal and physical harassment. For example, analysis of WRES data for 2016 and 2020 indicates that ME workers in the NHS are significantly more likely to experience discrimination at work from managers and co-workers. All staff included in these data were equally likely to experience harassment or bullying from patients (Kline etal., Reference Kline, Naqvi, Razaq and Wilhelm2017). However, other studies indicated that ME healthcare staff, including students in placements, were subjected to more bullying and harassment incidents from patients (Birks etal., Reference Birks, Cant, Budden, Russell-Westhead, Özçetin and Tee2017; Howells etal., Reference Howells, Bowera and Hassell2018; Qureshi etal., Reference Qureshi, Ali and Randhawa2020). An international comparative study, focusing on nursing students in Australia and the UK, shows higher reported bullying rates among male students in the UK (Birks etal., Reference Birks, Cant, Budden, Russell-Westhead, Özçetin and Tee2017). UK students from black or African ethnicity, and those with English, not their first language, reported the highest levels of bullying during their placements work. These bullying incidents ranged from subtle public humiliation, feelings of injustice and unfair treatment at work to physical (including sexual) harassment.

Johnson etal. (Reference Johnson, Cameron, Mitchinson, Parmar, Opio-te, Louch and Grange2019) established direct relationships between being subjected to bullying in the workplace and burnout with an indirect relationship with patient safety. The same study found that the prevalence of experiencing discrimination by colleagues or co-workers was three times higher for minority workers when compared to the majority ethnic group. Furthermore, certain groups of ME health and care workers face additional challenges due to overlapping ethnic, race, religious and migration identities (Younis and Jadhav, Reference Younis and Jadhav2020).

Overt and covert bullying and discrimination from people receiving care and patients toward ME social care workers were presented in many studies as almost normal expectations (Stevens etal., Reference Stevens, Hussein and Manthorpe2012; Tinarwo, Reference Tinarwo2017; Manthorpe etal., Reference Manthorpe, Harris, Moriarty and Stevens2018; Spiliopoulos etal., Reference Spiliopoulos, Cuban and Broadhurst2020). Manthorpe etal. (Reference Manthorpe, Harris, Moriarty and Stevens2018) indicate that managers felt that overt and covert racism from care users towards ME staff appeared less common than in the past. Nevertheless, it remained a source of conflict and demanded high support from supervisors and managers. However, recent in-depth research suggests that ME workers report significantly lower levels of managerial support (Hussein, Reference Hussein2018). Spiliopoulos etal. (Reference Spiliopoulos, Cuban and Broadhurst2020) identify how other identities, such as migration, and the specific local context, such as being located in rural communities, entrench the familiar feelings of ‘otherness’ not only due to the behaviours of people using care services but by the wider community as well. This was particularly the case among migrants identifying themselves as ‘dark-skinned', including those from the Philippines. They also explain how participants felt that it was expected from them to ‘blend in’ and absorb the implications of being ‘othered’ while maintaining their professional integrity. The review highlights that such experiences were not exclusive to rural locations, with existing stereotypes fostering discriminatory and harassment behaviour in urban and rural settings (Stevens etal., Reference Stevens, Hussein and Manthorpe2012; Sahraoui, Reference Sahraoui2019; Farris, Reference Farris2020).

The impact of COVID-19 on minority ethnic health and social care workers

Frontline healthcare workers from racial minority groups were at increased risk of being infected with or dying from COVID-19 (Nguyen etal., Reference Nguyen, Drew, Graham, Joshi, Guo, Ma, Mehta, Warner, Sikavi, Lo, Kwon, Song, Mucci, Stampfer, Willett, Eliassen, Hart, Chavarro, Rich-Edwards, Davies, Capdevila, Lee, Lochlainn, Varsavsky, Sudre, Cardoso, Wolf, Spector, Ourselin, Steves and Chan2020; Otu etal., Reference Otu, Ahinkorah, Ameyaw, Seidu and Yaya2020; Shields etal., Reference Shields, Faustini, Perez-Toledo, Jossi, Aldera, Allen, Al-Taei, Backhouse, Bosworth, Dunbar, Ebanks, Emmanuel, Garvey, Gray, Kidd, McGinnell, McLoughlin, Morley, O’Neill, Papakonstantinou, Pickles, Poxon, Richter, Walker, Wanigasooriya, Watanabe, Whalley, Zielinska, Crispin, Wraith, Beggs, Cunningham, Drayson and Richter2020). The first eleven UK doctors to die from COVID-19 were of ME backgrounds. Accounting for other risk factors, Nguyen etal. (Reference Nguyen, Drew, Graham, Joshi, Guo, Ma, Mehta, Warner, Sikavi, Lo, Kwon, Song, Mucci, Stampfer, Willett, Eliassen, Hart, Chavarro, Rich-Edwards, Davies, Capdevila, Lee, Lochlainn, Varsavsky, Sudre, Cardoso, Wolf, Spector, Ourselin, Steves and Chan2020) show that ME healthcare workers in the UK are at exceptionally high risk of infection, with at least a fivefold increased risk of COVID-19 compared to the general white population. The same study shows that healthcare workers from minority ethnic groups reported higher levels of reuse of, or inadequate access to, personal protective equipment (PPE), even when controlling for other factors, including exposure to patients with COVID-19. Otu etal. (Reference Otu, Ahinkorah, Ameyaw, Seidu and Yaya2020) point to potential links between the less empowered position of ME workers in the NHS and higher COVID-19 infection and death rates. They argue that due to the lack of empowerment of ME workers, they tended to accept working in hazardous situations, for example, when PPE supply is less adequate than for their White counterparts. They further make the case that continued and systematic discrimination as the underlying causes of such lack of empowerment, citing significantly higher levels of reported bullying incidents among ME NHS staff. Some of the COVID-19 related disparities are linked to genetic, disease, and social determinants of health. The latter is related to inequalities in income distribution, work patterns, residency in large cities and overcrowded accommodations (Otu etal., Reference Otu, Ahinkorah, Ameyaw, Seidu and Yaya2020).

Iob etal. (Reference Iob, Frank, Steptoe and Fancourt2020) examined the severity of depressive symptoms among individuals at high risk of COVID-19, specifically focusing on ethnicity. They concluded that ME groups were at higher risk of depressive symptoms since the onset of COVID-19 and the introductions of lockdowns and other infection control measures. However, these results were explained by other factors such as social support and were not specific to health and social care workers. In the social care sector, Hussein etal. (Reference Hussein, Saloniki, Turnpenny, Collins, Vadean, Bryson, Forth, Allan, Towers, Gousia and Richardson2020) examined the impact of COVID-19 on frontline workers in the UK through a survey of 296 participants in July-Aug 2020. The analysis highlights significantly increased workload and working hours and a decline in reported job security among all workers since the onset of the pandemic. Nearly half indicated their general health worsened, 60 per cent reporting an increase of incidents where their work had made them feel depressed, gloomy or miserable since the pandemic and over half reporting a reduction in the level of their work enthusiasm and optimism. The same study showed a reduced job satisfaction among a sizable group of social care workers, with two-fifths (42 per cent) of respondents indicating being a little or a lot less satisfied with their jobs since the onset of the pandemic.

Discussion

The current review provides evidence that racialised workers in health and social care employment in the UK have adverse employment outcomes throughout the employment process from recruitment to workplace experience and retention. These effects are present among low-paid jobs within sectors that suffer from generally difficult working conditions such as care work. Furthermore, workers with multiple identities related to race, gender and migration, for example, experience some of the most challenging experiences. Employment adverse outcomes include deskilling, downward job mobility, being subjected to overt and covert harassment and bullying incidents, reduced social support at work and a higher likelihood to enter formal disciplinary procedures. These experiences have negative consequences on racialised health and care workers, including levels of stress and burnout (Hussein, Reference Hussein2018; Johnson etal., Reference Johnson, Cameron, Mitchinson, Parmar, Opio-te, Louch and Grange2019). There is also evidence that ME staff in these settings feel less valued by the organisations and have less belief in their work environment to be fair and able to deal effectively with harassment and bullying (Howells etal., Reference Howells, Bowera and Hassell2018; Kline etal., Reference Kline, Naqvi, Razaq and Wilhelm2017; Bimpong etal., Reference Bimpong, Khan, Slight, Tolley and Slight2020; Wang and Seifert, Reference Wang and Seifert2020).

The literature identified through this review links the over-representation of ME workers in low paid jobs, including health and social care, to historical segmentation and selection practice into specific sectors and occupations (Hudson etal., 2017). Furthermore, income reliance due to socio-economic disadvantages and having families and caring responsibilities act as push factors to accept low-paid, local jobs in social care among minority ethnic workers (King etal., Reference King, Ryan, Wood, Tod and Robertson2020). These ‘sorting’ processes of particular groups into lower-paid occupations exacerbate racialised and gendered stereotypes of caring jobs, particularly those involving domiciliary and live-in care (Atkinson and Crozier, Reference Atkinson and Crozier2020; Farris, Reference Farris2020).

One of the main explanatory factors of these observed deferential are linked by several authors to ‘white hierarchy’ and the ‘ruling relations’ between senior teams and other workers as well as institutional and structural racism where unspoken rules favour white and male professional staff for better jobs (Howells etal., Reference Howells, Bowera and Hassell2018; ; Sahraoui, Reference Sahraoui2019; Milner etal., Reference Milner, Baker, Jeraj and Butt2020; Qureshi etal., Reference Qureshi, Ali and Randhawa2020). Furthermore, several authors argued that ME workers internalise such structures within this construct, not seeing themselves ‘fitting in’ among the ‘white crowed’ senior colleagues and lack a role model in senior positions (Qureshi etal. Reference Qureshi, Ali and Randhawa2020).

The review highlights that race, religion and social markers interact with ethnicity and gender, further discouraging individuals from seeing themselves managing others and discouraging them, directly and indirectly, from applying to promotions (Howells etal., Reference Howells, Bowera and Hassell2018). Systematic pre-existing conceptions of the ‘qualities’ associated with individuals and groups of workers with particular characteristics shape interactions, behaviour and outcomes. Intersectionality and the impacts of the interplay of various layers of identities influence the degree of exposure to certain attitudes with specific groups, such as black men in rural areas and Muslim men being presented with the least favourable conditions and experiences (Stevens etal., Reference Stevens, Hussein and Manthorpe2012; Spiliopoulos etal., Reference Spiliopoulos, Cuban and Broadhurst2020; Younis and Jadhav, Reference Younis and Jadhav2020).

Several studies identified institutional and structural racism as the root cause of such differential experiences (Birks etal., Reference Birks, Cant, Budden, Russell-Westhead, Özçetin and Tee2017; Joseph, Reference Joseph2019; Howells etal., Reference Howells, Bowera and Hassell2018). These are particularly evident among black ethnic minorities, where the advantages of ‘whiteness’ and ‘white hierarchy’ act as hidden sources of privileges at work (Howells etal., Reference Howells, Bowera and Hassell2018; Joseph, Reference Joseph2019). These further interact with an ascription of deficiency to black workers’ credentials and qualifications (Tinarwo, Reference Tinarwo2017; Joseph, Reference Joseph2019). According to the review, these mechanisms are associated with ME workers perceiving themselves as distanced from the senior ‘white’ managers, who report discouragements and rejection of promotion applications. This affects both newly arrived migrants to the UK and second generations or more established ethnic and religious groups. The social connections between employees and managers embody flows of power and influence the recruitment and promotion processes, privileging some ethnic groups over others (Howells etal., Reference Howells, Bowera and Hassell2018; Sahraoui, Reference Sahraoui2019; Qureshi etal., Reference Qureshi, Ali and Randhawa2020; Milner etal., Reference Milner, Baker, Jeraj and Butt2020). The evidence shows that the onus of navigating and countering these differentials is, in the majority, shouldered and negotiated by the individual racialised workers, who report an active elaborate process to fit in and comply with a set of stereotypes and pre-existing (mis)conceptions to enhance their employment outcomes (Hammond etal., Reference Hammond, Marshall-Lucette, Davies, Ross and Harris2017).

However, this review also highlights some common less favourable conditions for all workers in low-paid health and social care jobs regardless of ethnicity. This is particularly evident in social care, where a significant minority are estimated to be effectively paid under the National Living Wage (Hussein, Reference Hussein2017a). Furthermore, all low paid workers in health and social care appeared to lack career progression opportunities (Hudson etal., 2017; Hudson and Runge, Reference Hudson and Runge2020); to be exposed to mistreatment from patients and service users (Kline etal., Reference Kline, Naqvi, Razaq and Wilhelm2017); and to be at a high risk of stress and burnout (Hussein, Reference Hussein2018). Several authors linked these experiences to inadequate funding, marketisation and the increased share of private organisations in the social care provision resulting in unfavourable working conditions and insecure employment to different groups of workers in the sector (Hussein, Reference Hussein, Christensen and Billing2017b; Sahraoui, Reference Sahraoui2019; Atkinson and Crozier, Reference Atkinson and Crozier2020; Farris, Reference Farris2020).

Minority ethnic health and care workers were disproportionally affected by COVID-19, with a significantly higher prevalence of infection and associated morbidity and mortality (Nguyen etal., Reference Nguyen, Drew, Graham, Joshi, Guo, Ma, Mehta, Warner, Sikavi, Lo, Kwon, Song, Mucci, Stampfer, Willett, Eliassen, Hart, Chavarro, Rich-Edwards, Davies, Capdevila, Lee, Lochlainn, Varsavsky, Sudre, Cardoso, Wolf, Spector, Ourselin, Steves and Chan2020; Otu etal., Reference Otu, Ahinkorah, Ameyaw, Seidu and Yaya2020; Shields etal., Reference Shields, Faustini, Perez-Toledo, Jossi, Aldera, Allen, Al-Taei, Backhouse, Bosworth, Dunbar, Ebanks, Emmanuel, Garvey, Gray, Kidd, McGinnell, McLoughlin, Morley, O’Neill, Papakonstantinou, Pickles, Poxon, Richter, Walker, Wanigasooriya, Watanabe, Whalley, Zielinska, Crispin, Wraith, Beggs, Cunningham, Drayson and Richter2020). While pre-existing health conditions might explain some of the observed differences, the review highlights the effect of social determinants of health, institutional racism and lack of empowerment of racialised workers as further explanatory factors.

The current dynamic policy landscape of increased demands for health and social care, funding pressures, changing immigration systems due to Brexit and challenges associated with the global COVID-19 pandemic calls for targeted interventions to reduce, and ideally eliminate, existing ethnic inequalities within these sectors. For example, interventions might include proactive and positive actions to address racialised workers’ current ‘low pay traps and restrictive opportunities’ through a fairer and more elaborate recruitment process (Hudson etal., 2017; Sarfo-Annin, Reference Sarfo-Annin2020). Interventions to reduce discrimination in recruitment practices include introducing discrimination law, monitoring the organisation’s diversity, and anonymisation of the recruitment process as much as possible (Lloyd, Reference Lloyd2010; Larsen and Di Stasio, Reference Larsen and Di Stasio2019).

These and other interventions call for organisational level changes, such as introducing procedures to raise awareness of bullying and provide a bullying reporting mechanism, as well as individual-level interventions such as the provision of training and education to change behaviours or perceptions in a way that ensures responsibilities are placed on the perpetrators of bullying rather than the victims (Gillen etal., Reference Gillen, Sinclair, Kernohan, Begley and Luyben2017). Support structures also need to be put in place, such as creating ‘communities of practice’ (King etal., Reference King, Ryan, Wood, Tod and Robertson2020) and ‘safe spaces’ (Ross etal., Reference Ross, Jabbal, Chauhan, Maguire, Randhawa and Dahir2020) to facilitate career progression and empower workers’ voices.

The findings from this review emphasise the need to continue developing a solid set of national policies, laws, and strategies specific to reducing ethnic inequalities in the workplace, recognising these to be essential but not sufficient to ensure significant change. For example, Government plans and strategies could be further developed to address the disproportionate levels of precarious work arrangements and the pay inequalities observed among ME workers in health and social care. In addition, such policies need to be more specific to target disparities faced by disadvantaged workers due to multiple characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, age and profession.

Conclusion

The current review provides evidence of the significant contribution of workers from ethnic minorities to the health and adult social care sectors. Despite this, they face several adverse work experiences and outcomes across the whole employment process, from the recruitment process to career progression and burnout. Ethnic pay-gap and under-representation of workers in senior positions in both sectors appear to be persistent and ongoing. In addition, the intersectionality of visible markers – such as gender, migration status and religion – places certain groups, such as black Muslim men, at the lowest hierarchy of outcomes.

A substantial body of the literature links the observed poorer work outcomes among racialised workers in health and social care to historical and current institutional racism and discrimination. These are manifested in sorting workers into certain occupations and pay bands and in creating power hierarchies within the workplace, further influencing workers’ (in)abilities to progress. Furthermore, especially in social care, marketisation, outsourcing, and a mixed funding model negatively affect most low-paid workers’ job security and outcomes, with minority ethnic workers being exposed to mistreatment and lack of in-work social support.