Water security, defined as the reliable availability of adequate, acceptable and safe water, is key for basic household needs and to achieving an adequate, nutritious and high-quality diet(Reference Jepson, Wutich and Colllins1). Currently, the inadequate use of water globally presents significant risks to health, food and development(Reference Young, Miller and Frongillo2). Water is needed for agriculture, raising livestock and all processes of production; in 2014, nearly 70 % of the available fresh water was used to produce food(3).

Even when there is enough water physically available to fulfil human needs, some vast geographical areas are near the total water scarcity, affecting millions of people, of which many are the most vulnerable, poor and disadvantaged. Therefore, the implementation and management of integrated and sustainable policies for water conservation throughout the agricultural production chain are critical.

The concept of water for food security and nutrition is gaining prominence(4). Food security and nutrition includes potable water and sanitation; water used to produce, process and prepare food; and water use across all livelihood and income sectors(Reference Mehta, Oweis and Ringler5). The latter implies a direct pathway to economic food access, that is, food affordability. Furthermore, food security and nutrition includes the objective of sustainable management and conservation of water resources and the ecosystems that sustain them(6).

In the nutrition literature, the role of water access and use in food security, nutrition and well-being has not been thoroughly documented(Reference Young, Frongillo and Jamaluddine7,Reference Miller, Workman and Panchang8) . Instead, the role of water in this literature has been focused on the role of sanitation and hygiene (WASH) in diarrheal illnesses and child development, and more recently, on environmental enteropathy(Reference Miller, Vonk and Staddon9). Hydration in the context of sports nutrition has also received some attention(Reference Miller, Workman and Panchang8). Although water plays roles beyond enteric infections and homeostasis of corporal water, it has received far less attention than other essential nutrients. Water insecurity (WI) affects many other nutrition-related phenomena, such as agricultural production, food preparation and handling, dietary behaviour, dietary diversity, infant and child feeding practices and energy use(Reference Humphrey10–Reference Jéquier and Constant14), and therefore deserves more attention.

It has been established that the availability of adequate and safe water is fundamental to promoting the four pillars of food security: availability, accessibility, food utilisation and stability(Reference Nath15). For this reason, the universal guarantee of water is one of the UN Sustainable Development Goals for 2030. The corresponding 2030 Agenda states that to monitor the progress of this objective and understand the role of water in the fight to reduce food insecurity (FI), it has become critical to develop a scale to measure household WI(Reference Nounkeu and Dharod16).

However, Young et al. recently documented that experiencing WI significantly increases the likelihood of also experiencing FI in several regions of the world. This suggests the importance of considering WI when designing food and nutrition policies and interventions, although more research is needed to fully understand the connections between these insecurities(Reference Young, Bethancourt and Frongillo17).

In Mexico, experiences of household food security have been measured for the last several decades using the Latin American and Caribbean Food Security Scale (in Spanish, ELCSA)(Reference Perez-Escamilla, Paras and Hromi-Fiedler18,Reference Gaitán-Rossi, Vilar-Compte and Teruel19) . In 2012, Mexico’s National Institute of Public Health added it to the national health and nutrition survey(Reference Mundo-Rosas, Shamah-Levy and A Rivera-Dommarco20) and has since been measuring it regularly. In the last decade, moderate-to-severe FI in Mexico has hovered between 25·9 and 28·2 %(Reference Mundo-Rosas, Shamah-Levy and A Rivera-Dommarco20,Reference Shamah-Levy, Romero-Martínez and Barrientos-Gutiérrez21) .

There is growing concern about water issues in Mexico, including scarcity, flooding and contamination(Reference Lankao22). To understand how problems with water affect public health, the National Institute of Public Health innovated by adding a national-level measurement of WI experiences in Mexico in 2021. The Household Water Insecurity Experiences (HWISE) Scale, which measures experiences of difficulties with water availability, access, use and stability(Reference Young, Boateng and Jamaluddine23), was applied as part of the Nutrition Survey-Continuous 2021 (in Spanish, ENSANUT-Continua 2021).

The objective of this study was to evaluate the role that water security plays in food security in Mexican households. Specifically, we analysed how experiencing WI (HWISE ≥ 12) is related to moderate-to-severe FI and other covariates.

Methods

The ENSANUT-Continua 2021 is a probabilistic and stratified national survey using cluster samples and regional representation. ENSANUT-Continua 2021 collected data from 12 619 households representing 36,476,972 Mexican households. Data were collected from August to November of 2021. The seasons of the year include summer and autumn, with the latter seeing major hurricanes in various regions of the country. Data were collected by trained enumerators in real time using tablets. Further details on the survey sample can be found elsewhere(Reference Romero-Martínez, Barrientos-Gutiérrez and Cuevas-Nasu24).

Respondents generally corresponded to the person recognised as the head of household or any other household member aged 18 or older who was familiar with the household members and conditions.

Variables

Food security was evaluated using the ELCSA, validated and adapted for Mexico(Reference Melgar-Quiñonez, Zubieta and Valdez25,Reference Mundo-Rosas, Unar-Munguía and Hernández-F26) . It includes fifteen yes/no questions about lacking money for food, concerns about food supplies running out (mild FI), reduced diet diversity and quality (moderate FI) and limited food quantity and hunger (severe FI)(27). The scale, directed at the head of the household or the member responsible for food, has a 3-month recall period. Scoring depends on positive responses and the presence of children under 18. For households without children under 18, 0 indicates food security, 1–3 mild FI, 4–6 moderate FI and 7–8 severe FI. For children under 18 years of age, 0 indicates food security, 1–5 mild FI, 6–10 moderate FI and 11–15 severe FI(Reference Melgar-Quiñonez, Uribe and Centeno28).

The most recent definitions of ‘water security’ consider four dimensions: access, which refers to the ability of an individual or household to obtain water (by travelling to the water source, being able to pay for water supply, etc.). Availability considers the presence of water (‘available’). Use considers and distinguishes between the acceptability and safety of the water that individuals/households have access to (e.g. some types of water are used only for irrigation and not for human consumption). The dimension of stability or reliability simultaneously encompasses the uninterrupted existence of the three previous dimensions(Reference Varis, Keskinen and Kummu29). Household WI is defined as the inability to access and benefit from adequate, reliable and safe water for well-being and healthy living(30). The HWISE was developed to measure the less-explored dimensions of water security. This scale is a validated tool used in several middle- and low-income countries (including some regions of Mexico) that inquired about access to and reliability of water within households.

The HWISE scale has been established as reliable, equivalent and valid in within- and cross-country analyses. Two Mexican cities were included in the validation study of HWISE(Reference Young, Boateng and Jamaluddine23). Although the scale had already been translated into Spanish, it was considered important to pilot test the scale before including it in ENSANUT because of the cultural variety in Mexico. A group of researchers (including those who conducted the validation study) and experienced interviewers held work sessions to review and harmonise the phrases contained in each question and make the intended meaning of the items understandable. Once the first proposal of the harmonised scale was available, it was tested in 200 households in 30 states of the country, to review the comprehension of the questions and the need to include locally relevant examples. Based on the pilot study, the response to items 4, 9 and 12 was improved(Reference Shamah-Levy, Mundo-Rosas and Muñoz-Espinosa31).

The HWISE Scale comprises twelve questions about households’ experiences related to WI during the previous 4 weeks. The questions asked about the frequency of life-disrupting water-related problems, such as worrying about water, feeling shame about the household water situation, having to change what was eaten due to water problems and going to sleep thirsty. Possible responses are ‘never’, scored as 0; ‘rarely’, scored as 1; ‘sometimes’, scored as 2; and ‘often/always’, scored as 3. The range is 0–36; scores of 12 or higher are classified as water insecure(Reference Rosinger and Young32).

Wealth was measured using the household well-being index (HWI), which has been used in previous ENSANUT(Reference Vyas and Kumaranayake33). The HWI was constructed through principal component analysis generated using a polychoric correlation matrix(Reference Drasgow, Kotz and Johnson34). The first component qualified as HWI, which included 40·5 and 51 % of the total variability of the included characteristics for its construction in 2012 and 2018, respectively. These were calculated using the following variables: material used to construct the dwelling (ceiling, walls and floors), number of rooms, provision of water and light services, possession of a car, number of household appliances (refrigerator, stove, washing machine, kettle, microwave oven, etc.) and the number of electronic devices (television, cable, radio and telephone). As previously described, HWI was classified into tertiles (1 = low, 2 = medium and 3 = high).

Localities with more than 2500 inhabitants were classified as urban areas, whereas those with less than 2500 were classified as rural areas.

As for the region, the ENSANUT-Continua 2021 defines nine geographic regions made up of contiguous federal entities and their population density and have been used by the Institute of Geography and Statistics to report the country’s statistics: (i) North Pacific (Baja California, Baja California Sur, Nayarit, Sinaloa and Sonora); (ii) Border (Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo León and Tamaulipas); (iii) Central Pacific (Colima, Jalisco and Michoacán); (iv) Central North (Aguascalientes, Durango, Guanajuato, Querétaro, San Luís Potosí and Zacatecas); (v) Central (Hidalgo, Tlaxcala and Veracruz); (vi) Mexico City; (vii) Mexico State; (viii) South Pacific (Guerrero, Morelos, Oaxaca and Puebla); and (ix) Peninsula (Campeche, Chiapas, Quintana Roo, Tabasco and Yucatán)(Reference Romero-Martínez, Barrientos-Gutiérrez and Cuevas-Nasu24).

Household size was determined based on the number of household members reported to share common household expenditures. Households in which any member spoke an indigenous language were classified as indigenous, as the previous ENSANUT.

Statistical analysis

Variables of interest were expressed as estimated totals and proportions with 95 % CI. We described the association of experiencing WI (HWISE ≥ 12) with geographic regions, HWI and the number of household members as covariates, as well as the role of WI as a mediating factor for experiencing moderate-to-severe FI, including the contribution of determinants such as correspondence to rural areas and indigenous household head as FI covariates. A generalised path analysis model(Reference Tsai, Shau and Hu35) was used to measure the contribution of different factors to the probability of experiencing WI as a binomial response, and its contribution to moderate and severe FI was included as a binomial response, both using a logit response transformation. The estimated coefficients and their respective OR were used to support this interpretation. All analyses accounted for the design of the study in the module of complex sampling ‘svy’ and the ‘gsem’ command in STATA, v.16·1.

Results

Of the 12 619 households visited, 12 520 had complete information of ELCSA and 12 463 on the HWISE scale. Of the population, 74·1 % had food security or mild FI, while 15·8 % had moderate FI, and 10·1 % had severe FI (Table 1). WI (HWISE scores ≥12) was experienced by 16·3 % of the population. The measure of wealth, given the use of tertiles of the HWI, suggests that the sample population is balanced across the index categories.

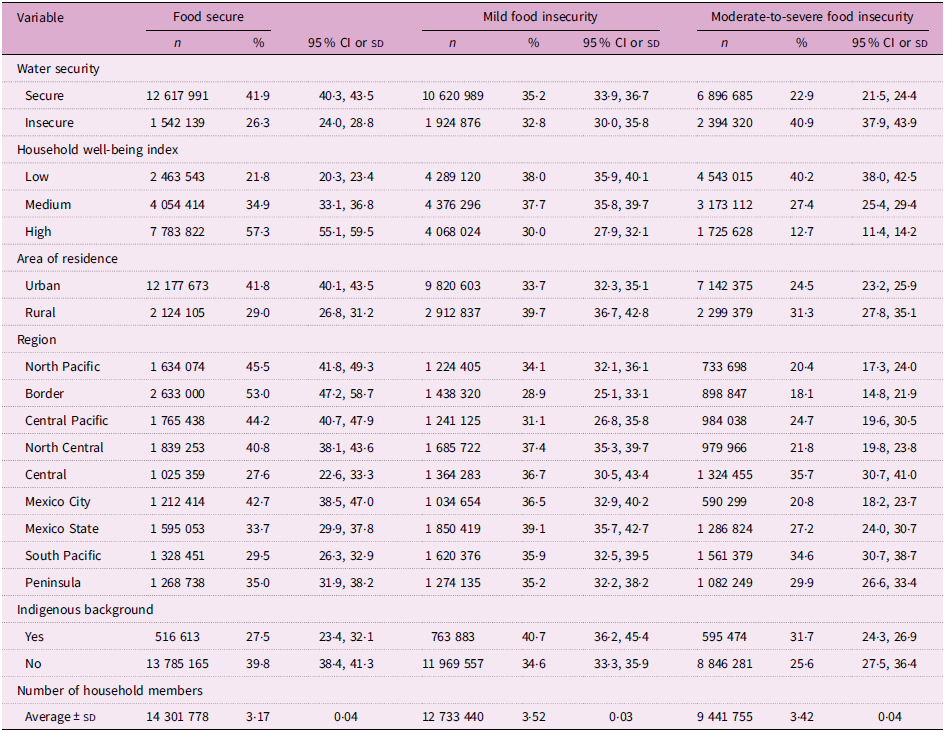

Table 1. Characteristics of sampled households in Mexico, ENSANUT-Continua 2021

HH, household; FI, food insecurity.

* HWI was classified in terciles.

† Indigenous background if any member of the household spoke an indigenous language, was classified as an indigenous household.

The sample included 688 households in which the head of household spoke an indigenous language, representing 5·1 % of the national population. The average number of members per household was 3·36.

Table 2 shows conditional probabilities (expressed as percentages) of FI, given WI and other covariates. It is clear that 40·9 % of households experiencing WI showed moderate-to-severe FI and only 26·3 % were food secure. In contrast, just 22·9 % of water-secure households showed moderate-to-severe FI, while 41·9 % were food secure.

Table 2. Characteristics of the ENSANUT-Continua 2021 participants, by food security status

FI was also strongly associated with low scores of HWI. The prevalence of food security was 21·8 % in households in the low-WI tertile, and up to 40·2 % reported moderate-to-severe FI. On the other hand, 57·3 % of households with high HWI scores were food secure, and only 12·7 % showed moderate-to-severe FI.

FI was also strongly associated with a low HWI score. The prevalence of food security was 21·8 % in households in the low-WI tertile, and up to 40·2 % reported moderate-to-severe FI. In contrast, 57·3 % of households with high HWI scores were food secure, and only 12·7 % showed moderate-to-severe FI.

Food security was measured at 41·8 % in urban areas and 29 % in rural areas, and the prevalence of moderate-to-severe FI was greater in rural areas (31·3 %) than in urban areas (24·5 %).

The prevalence of food security was lower in households in which the head speaks an indigenous language (27·5 %) than in their non-indigenous language-speaking counterparts (39·8 %, Table 2).

By region, both FI and WI were least prevalent in the Border region (Fig. 1); this region has the highest HWI scores in the country. Even though the northern region is one of the areas with the highest economic development and the largest in terms of land area, covering over 700 000 km2, rivers are scarce. Nonetheless, the construction of several dams has facilitated the establishment of agricultural zones and water storage. In contrast to other regions, the indigenous groups residing in this area are few(36). The Peninsula region had the highest prevalence of moderate-to-severe FI, and the Mexico State region had the highest levels of WI.

Figure 1. Proportion of households with moderate-to-severe food insecurity and water insecurity, by region of Mexico in the ENSANUT-Continua 2021.

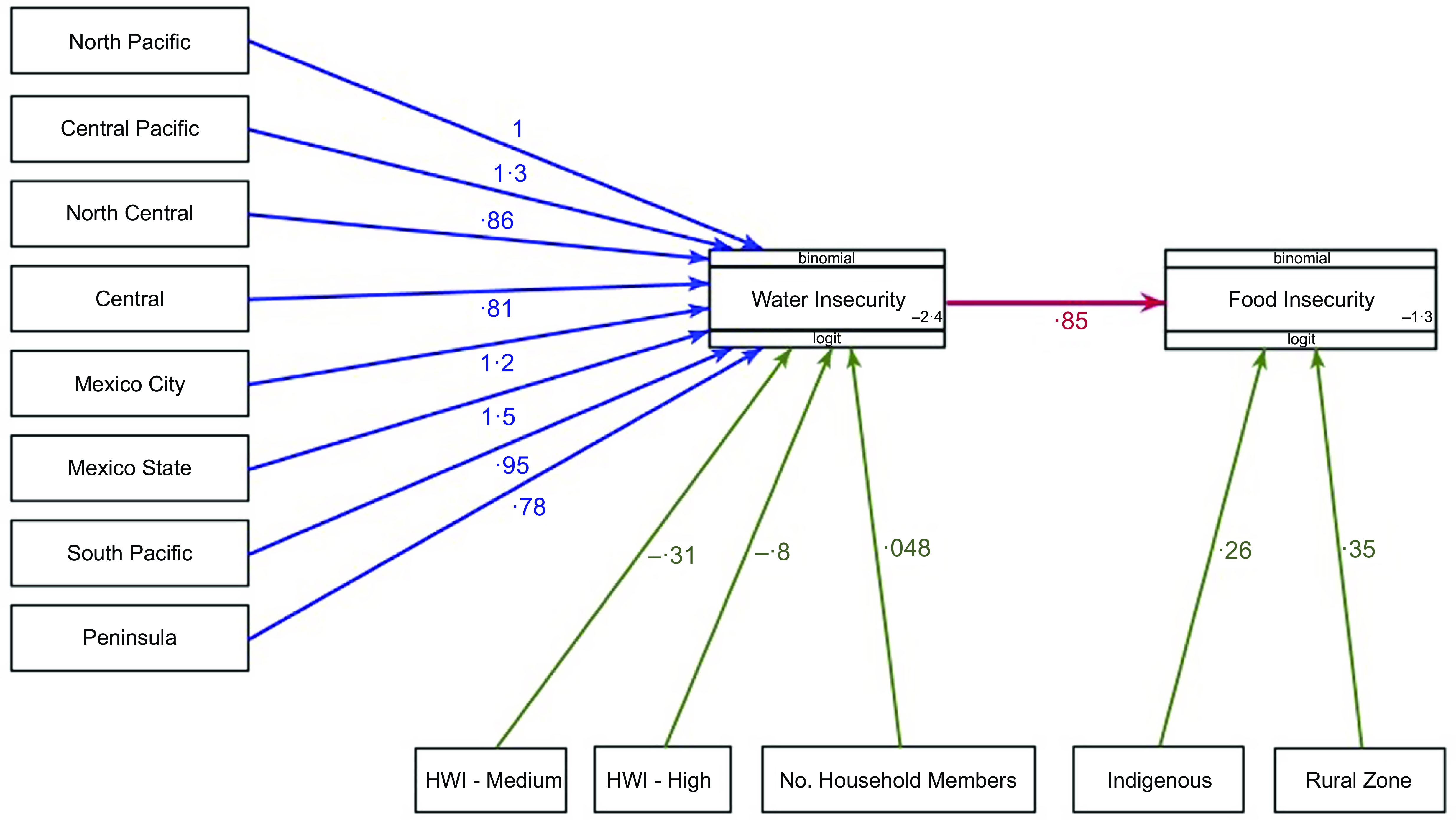

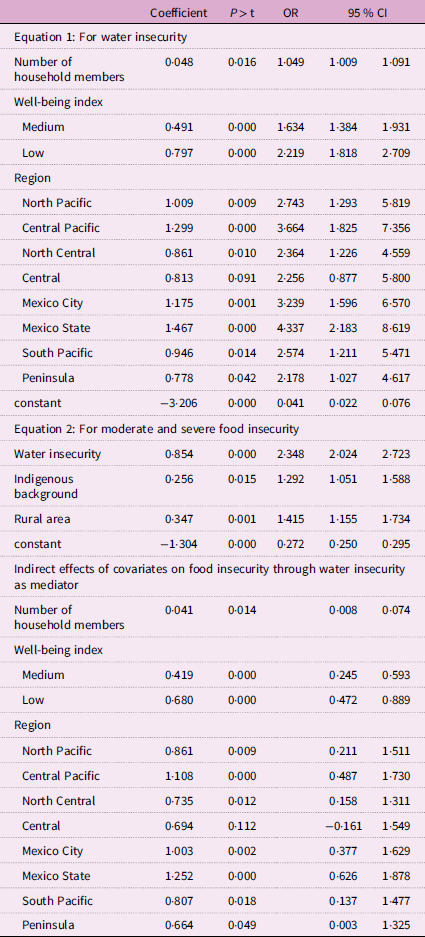

We utilised the information of 12 463 households with complete data of FI and WI data for generalised path analysis. The generalised path model (Fig. 2) produced two simultaneous logistical regression equations (Table 3). Equation 1 showed a significant positive association between the probability of WI and the number of household members (OR = 1·05; 95 % CI: 1·01, 1·09) and a significant positive relationship between medium and low scores of HWI and WI (OR = 1·63; 95 % CI: 1·38, 1·93 and OR = 2·22; 95 % CI: 1·82, 2·71, respectively), compared with high HWI.

Figure 2. Visual representation of the general path analysis model of water and food insecurity in the ENSANUT-Continua 2021.

Table 3. Generalised path model on the contributions of multiple factors to water security and food security in the ENSANUT-Continua 2021

As we can see, WI was more prevalent in certain regions, such as the North Pacific (OR = 2·74; 95 % CI: 1·29, 5·82), Central Pacific (OR = 3·66; 95 % CI: 1·82, 7·36), Mexico State (OR = 4·33; 95 % CI: 2·18, 8·62), Mexico City (OR = 3·24; 95 % CI: 1·60, 6·57), South Pacific (OR = 2·57; 95 % CI: 1·21, 5·47), North Central (OR = 2·36; 95 % CI: 1·23, 4·56) and Peninsula (OR = 2·18; 95 % CI: 1·03, 4·62). The Border region had the lowest prevalence of WI, and only the Central region (OR = 2·26; 95 % CI: 0·88, 5·8) came close to comparing with the relatively low WI reported in the former.

Equation 2 illustrates that there is a greatly increased probability of experiencing moderate-to-severe FI for households that are WI (OR = 2·35; 95 % CI: 2·02, 2·72). The probability of experiencing moderate-to-severe FI is also greater in indigenous households (OR = 1·29; 95 % CI: 1·05, 1·59) and rural households (OR = 0·42; 95 % CI: 1·16, 1·73). Notably, wealth and household size did not contribute directly to FI but did so indirectly through the mediating factor of WI. In the bottom section of Table 3, the indirect effects of household size, HWI and region on FI through WI as a mediator are quite similar to those observed as direct effects on WI. This explains why the direct effects of this covariate on FI disappear.

Discussion

These data demonstrate that experiences of WI have a strong positive association with moderate-to-severe FI in Mexican households. Strong associations between FI and WI have been observed in other studies, including a twenty-seven-site study in twenty-one low and middle-income countries(Reference Young, Boateng and Jamaluddine23,Reference Brewis, Workman and Wutich37) and a twenty-five-country study conducted in collaboration with FAO(Reference Young, Bethancourt and Frongillo17). These results are also consistent with other work that has posited WI as a plausible driver of FI(Reference Young, Frongillo and Jamaluddine7,Reference Rosinger, Bethancourt and Young38) , including the sole study with repeated measures of FI and WI(Reference Boateng, Workman and Miller39).

Our finding that FI is more severe in rural and indigenous households aligns with previous studies in Mexico, where households in rural and indigenous communities appear to be more vulnerable(Reference Young, Bethancourt and Frongillo17,Reference Magaña-Lemus, Ishdorj and Rosson40) . With ENSANUT 2012, it was found that nationally moderate-to-severe FI affected 28·2 % of the households.

Rural or indigenous households, akin to those in the lowest HWI tertile, were particularly impacted by moderate-to-severe FI, with rates of 35·4, 42·2 and 45·2 %, respectively. Close to one-third of Mexican households experienced these more severe forms of FI, especially prevalent in rural areas of the southern states, among indigenous communities, or in conditions of poverty(Reference Mundo-Rosas, Unar-Munguía and Hernández-F26). Notably, there was a decline observed in ENSANUT 2018, with rural households reporting a moderate-to-severe FI prevalence of 29·1 %(Reference Mundo-Rosas, Unar-Munguía and Hernández-F26), which decreased to 27·1 %(Reference Avila-Arcos, Humaran and Morales-Ruan41) in 2020. However, in 2021, this figure increased to 31·3 % in rural households(Reference Shamah-Levy, Romero-Martínez and Barrientos-Gutiérrez21).

Beyond Mexico, similar findings have been described in countries such as Guatemala and Colombia, which share similar sociodemographic characteristics and have implemented comparable strategies to address food security and WI challenges. In Guatemala, the marketing of food products has limited dietary diversity and supplanted the production and consumption of fresh nutritive foods, even in rural communities primarily dedicated to food production. This has caused the agricultural indigenous communities of Guatemala to appear much like the urban ‘food deserts’ described in higher-income countries(Reference Webb, Chary and De Vries42). In Colombia, a study among indigenous women demonstrated their vulnerability to FI and the complexities of autonomy, gender inequalities, discrimination and poverty(Reference Sinclair, Thompson-Colón and Bastidas-Granja43).

The association between WI and some of these structural factors, such as household size, area of residence and household wealth, has also been observed in previous studies(Reference Young, Boateng and Jamaluddine23,Reference Young, Bethancourt and Ritter44,Reference Jepson, Stoler and Baek45) . To the best of our knowledge, differences by indigenous background have not been reported. It will be interesting to determine whether such inequalities persist elsewhere.

It will be useful to understand how WI shapes FI and nutrition, for example, in food production, cooking and improving the palatability and digestibility of foods or in hygiene and the prevention of food and water-borne diseases(Reference Pickering and Davis46). Evidence of this relationship so far has shown that the lack of access to water affects agricultural production, especially in rural areas where agriculture is the primary source of both income and food. Contaminated water causes illnesses such as diarrhoea and reduces the quality of food produced. Furthermore, water scarcity can limit the overall production of food and increase prices, which can further reduce the capacity for low-income households to afford food(Reference Frongillo47).

Our study had certain limitations. The cross-sectional nature of the data did not allow us to infer causality. Additionally, in Mexico, no national-level indicator exists that allows the comparison of our measurements with others. Nevertheless, the data presented were derived from a representative and probabilistic national survey that previously used the ELCSA for food security measurement, and the HWISE scale used to measure WI has been previously validated in other countries, Mexico, and the context of the ENSANUT. The scale was also adapted to the country context, further strengthening the data presented that are derived from it(Reference Shamah-Levy, Mundo-Rosas and Muñoz-Espinosa31).

Both FI and WI are key determinants of population well-being that require immediate attention(Reference Young, Bethancourt and Cafiero48,Reference Melgar-Quiñonez, Gaitán-Rossi and Pérez-Escamilla49) . Given the close interaction between the two, it may be impossible to reduce FI without evaluating if WI is at play, which suggests that household food security interventions should include improvements in household water security(4). This area requires further exploration.

It is critical to sensitise Mexican citizens and leadership to the responsible use of water, in addition to implementing strategic investments in water infrastructure and sanitation to guarantee access to safe potable water. This would not only improve the health and food security of the population but would also contribute to the national economy.

Authorship

All the authors have contributed to the conception and design of the work and the analysis of the data in a manner substantial enough to take public responsibility for it; each one of us has reviewed the final version of the manuscript and approved it for publication. The authors had full access to the data and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing interests

There are no conflicts of interest.

Ethics of human subject participation

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by three committees: Research, Ethics in Research and Biosecurity Committee of the National Institute of Public Health of Mexico. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.