What sad and awful Scenes are these presented to your View; Let every one Example take, and Virtue’s Ways pursue. I

II

For here you see what Vice has done, in all it’s [sic] sinful Ways; By Mark and Phillis who are left, to finish now their Days.

III

The Sight is shocking to behold, and dismal to our Eyes; And if our Hearts are not o’er hard, will fill us with Surprize [sic].

God’s Vengeance cries aloud indeed, And now his Voice they hear, And in an Hour or two they must before his Face appear.

V

To answer for their Master’s Blood, which they’ve unjustly split; And if not Pardon’d, sure they must, Remain with all their Guilt.

VI

Their Crimes appear as black as Hell and justly so indeed; and for a greater, I am sure, there’s none this can exceed.

VII

Three were concerned in this Crime, but one by Law was clear’d; The other two must suffer Death, and ‘tis but just indeed.1

On Sunday morning, June 29, 1755, Phillis, an enslaved woman owned by Captain John Codman prepared breakfast as usual. The wealthy captain was a merchant and slaveholder who resided in the town of Charlestown in the colony of Massachusetts. A widower since 1752, Codman lived in the home with his children and enslaved people. Phillis prepared his usual breakfast of a bowl of water gruel – oatmeal – and gave it to his thirty-one-year-old daughter Elizabeth to give to her father. Codman, who had a history of stomach ailments, fell gravely ill shortly after finishing his breakfast. As his condition worsened, his children and enslaved cooks, Phoebe and Phillis, tended to him at his bedside with great tenderness and concern. The captain is said to have “languished for fifteen hours” in his bed, suffering from convulsions. He died two days later on July 1, 1755.

According to the Boston Evening Post, upon examining Codman’s body, Middlesex County Coroner John Remington noticed that his “lower Parts [had] turned as black as Coal.” Perplexed by the unnatural state of his body, Coroner Remington held a coroner’s inquest that began on July 2, the day after John Codman’s death.2 After his cause of death came to light, officials uncovered a diabolical conspiracy that dated back at least six years.3

…

Colonial Charlestown, Massachusetts, was a port city located roughly 2.5 miles north of Boston, and separated from it by the Charles River (Figure 1.1). Both whites and Blacks freely traveled between the neighboring cities of Charlestown and Boston for business and personal reasons. On any given day, enslaved people, merchants, or fishermen took the ferry to and from Boston, underscoring the connection between the two port cities.4 The economies of Charlestown and Boston both centered on trade, shipbuilding, fishing, and distilleries, but Boston was the more significant of the two. By the 1730s, Boston had the distinction of being the most prosperous port city in the British American colonies. Among the many goods traded on Boston’s Long Wharf and destined for other places in Massachusetts, other colonies in mainland North America, Barbados, and even England, were enslaved African men and women.

Figure 1.1 1775 Map of Charlestown and Boston

The earliest evidence of enslaved Africans in the Boston area can be traced to 1638 when a group arrived on the ship Desire. Still, slavery never became a dominant feature in Boston’s culture or economy. Most Boston slaveowners owned just one or two people as personal servants or artisans. Although it is hard to find accurate census data from colonial Massachusetts, roughly 280,000 people resided in the colony by the mid-eighteenth century. In 1754, when Governor William Shirley ordered a colony-wide census of enslaved people older than sixteen years old, there were 954 of them living in Boston (Suffolk County) – comprising roughly 5.6 percent of the city’s estimated total population of 17,000. An incomplete slave census of Middlesex County, where Charlestown was located, recorded just 353 enslaved adults in that county. Yet, together, Suffolk and Middlesex counties were home to the majority of Blacks living in the colony of Massachusetts in the mid-eighteenth century.5 Even before the American Revolution, slavery was on the decline in the area.

In 1750, 80 percent of Boston’s Black community consisted of free Blacks, most of whom resided in the city’s North End.6 Boston’s Black community was consequential: several Black Bostonians in the colonial era would later make their mark in history. The future poet Phillis Wheatley; future founder of the first Black Masonic lodge, Prince Hall; and Elizabeth “Mum Bett” Freeman, who successfully sued for freedom after the American Revolution, all lived in Boston in the 1750s.

Great fluidity existed between Boston and Charlestown: some enslaved people living in Charlestown had spouses and other family members living in North Boston, so it was not unusual for them to travel between the towns in both directions to visit their loved ones. John Codman’s enslaved people, for example, regularly visited Boston’s North End on errands, to visit spouses and friends, and for work and leisure activities. Black Boston, with its healthy and growing population of free Blacks, offered Codman’s enslaved people a taste of freedom. Perhaps, it was that taste that made them increasingly discontented with their owner.

John Codman was born on September 29, 1696, in Charlestown, Massachusetts, to Stephen and Elizabeth Codman. Both of his parents died by the time he was eight years old, so an older brother cared for him until adulthood. In 1718, John married Parnell Foster, the granddaughter of Mary Chilton, a pilgrim who had arrived from Europe aboard the Mayflower and who was, purportedly, the first woman to land at Plymouth. By the time Parnell Codman died on September 15, 1752, the couple had given birth to eleven children. A saddler by trade, Codman also worked as a merchant and sea captain. In those various endeavors, he managed to amass a great deal of wealth: his estate, which was valued at £6,000 in 1749 (equivalent to $1,385,773 today), included a “mansion,” a ship, a forge, seven enslaved people, thirty acres of land in Bridgewater and fifty acres of land near Harvard College. Historian Lorenzo Greene’s research listed John Codman among the leading slaveholders in the Massachusetts colony. Captain Codman also was an ensign, or junior officer, in the first (and now oldest) chartered military organization in the western hemisphere, the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company. Posthumously, he was described by elite local whites as a “remarkably upright man both in person and character, and was greatly respected.”7 However, Codman’s enslaved people did not think so highly of him as the white elites in Charlestown and Boston.

In 1755, Captain Codman owned seven enslaved people: Pompey, Cuffee, Scipio, Thomas (Tom), Phillis, Phoebe, and Mark, all of whom worked as mechanics, common laborers, or house servants.8 Phillis had grown up in the Codman household. In her late thirties in 1755, she was described as the “spinster servant of John Codman,” which was a seventeenth-century term to describe an unmarried woman. She and Phoebe were the only two enslaved women owned by the captain. According to Mark, Codman “favored” Phoebe and treated her better than the others. Phoebe was “married” to a man named Quacoe. The couple did not legally marry, but were recognized as husband and wife by contemporary Black and white Charlestowners. The archive does not reveal how the two met or where they married. Quacoe lived in Boston with his owner, James Dalton, who owned a restaurant; he sometimes spent the night and weekends with his wife in the Codman garret in Charlestown.9

Quacoe had a long and notorious history. Likely born in Africa or to an African mother judging by his Akan name, he may have been transported in the Transatlantic Slave Trade to the Dutch colony of Surinam, where he was enslaved most of his life. Quacoe and a female accomplice had been accused of poisoning in Surinam. In Surinam, people such as Quacoe, who poisoned and used knowledge of plants and herbs for evil, were called wisimen by fellow enslaved people.10 Quacoe’s female accomplice was executed for the crime, but he was sentenced to transportation out of Surinam, which is how he arrived in Boston. The 1755 Codman murder is the second time Quacoe had been implicated in a poisoning; it would not be his last. In 1761, five years after Codman’s death, a dying slave named Boston accused Quacoe of poisoning him before he died. That case began with an argument over a woman between Quacoe and Sambo, another enslaved man. Shortly thereafter, Sambo’s pigs were found dead – poisoned. Many enslaved people immediately suspected that Quacoe had poisoned the pigs as revenge. Reportedly, he had felt betrayed when his own friend, Boston, took Sambo’s side in the dispute. Boston then fell deathly ill, and before dying, he accused Quacoe of poisoning him. Quacoe escaped a conviction and death sentence because the justice overseeing his case did not believe an allegation alone was enough to convict him of the crime.11 What this history reveals is that Quacoe was a master poisoner who used his craft to exact revenge when wronged. He is, perhaps, the only enslaved person in that era who was implicated in multiple poisoning murders in the Black Atlantic and escaped a death sentence each time.

Mark is the only Codman slave for whom there is more biographical data available – much of it provided in his own dying declaration, The Last & Dying Words of Mark. Mark stated that he had been born in Barbados in 1725 and sold as a child to Henry Caswell of Boston. In the colonial era, ships routinely traded between Boston and Barbados so his transportation to the colony was not unusual, but certainly traumatic to the young child who was permanently separated from his family and community. Mark’s second owner, John Salter, was a Boston brazier, or brass worker, by trade. Salter had had a transformational impact on young Mark by teaching him to read and write. Mark fondly recalled that Salter “educated me as tenderly as one of his own children. In the colonial era, owners rarely taught enslaved people to read. Owners who recognized their enslaved people’s humanity might teach them to read so that they could read the Bible. Mark was a Christian, so being able to read the Bible was important for his spiritual growth. For reasons unknown, Salter sold Mark to Joseph Thomas of Plympton, Massachusetts, located roughly forty-five miles south of Boston. Thomas subsequently sold Mark to Captain John Codman. Mark had a wife and at least one child in Boston. The record is silent on their identities or whether they were enslaved or free. Mark indicated that Codman “let me live in Boston with my Wife, and go out to work.” A blacksmith by trade, and literate, Mark had many more freedoms and privileges than typical enslaved people in the colonial era. Codman allowed him to find his own work, earn his own wages, and live with his wife and child in Boston. While hiring out their own time – especially in another city – enslaved people needed to find their own employers and housing. It was not uncommon for hires to reside with their enslaved family members. Living and working separately from Codman and earning his own wages afforded Mark some freedom and independence. For one, he moved freely between Charlestown and North Boston. By his own admission, though, he spent too much of his free time drinking, visiting friends, and “carousing” on Sabbath. His drinking was such a problem that Codman tried to stop it by telling the owner of a pub Mark frequented not to sell any more alcohol to his servants.12

In 1752, a warrant was issued for Mark’s arrest in Boston after he had ignored its “warning out” notices to leave the city. The warning out process began with legal notices to non-residents ordering them to return to their legal towns of residence. The intention was to ensure that transients and indigents would not apply for poor relief in their adopted towns, but would, instead, put that burden on their legal places of residence. For most white newcomers, warning out was not always enforced, but Blacks could not expect the same privilege of whiteness.13 The record is silent on whether Boston officials arrested Mark and forced him back to Charlestown in 1752. What is certain is that he continued to spend his free time in Boston.

It is hard to determine, with certainty, the quality of the lives Codman’s enslaved people enjoyed. All except Mark lived in the garret of the home. The inventory of Codman’s estate after his death provides clues about their material conditions in the garret. There were five straw beds, one feather bed, and ten rugs in that common living space.14 It was highly unusual for enslaved people in the colonial era to sleep on a feather bed; these typically were found in the homes of the wealthy. Poor whites and enslaved people generally slept on the floor or straw beds. Hence, the presence of the feather bed among five straw beds in the garret where they slept suggests that one of Codman’s enslaved people received special treatment. Given what Mark revealed about Phoebe being favored, it is highly likely that the feather bed belonged to her.

None of the people owned by Captain Codman ever explicitly stated that he was an abusive or neglectful owner, but there were clues that he was. Right before his death, he had hit Tom so hard that he injured his eye. Codman’s people clearly had their own image of what character traits defined “good masters” because they expressed the desire to have one during the coroner’s inquest following his death. Implicit in this expressed desire for “good masters” is the judgment that Codman was not a good owner.15 Codman’s people gave the coroner’s inquest jury several reasons why they considered him such. According to Phillis, Mark said he was “uneasy and wanted to have another Master, and he was concerned for Phebe and [Phillis] too.” Although she was not forthcoming on the specific nature of Mark’s concerns, it must be noted that he did not express the same “concern” for Codman’s enslaved men; the inference is that the women were enduring a distinctive gendered experience in the Codman household. Perhaps, Mark’s “concern” is related to the burden of the women’s workload as house servants and cooks or it may be a subtle reference to sexual abuse – a regular feature of Black women’s enslavement. The use of veiled terms and euphemisms to discuss sexual abuse is a product of the era; in the interest of decorum and taste, people in colonial American did not discuss sex or rape publicly. It is reasonable to think that as a widower, Codman might have forced his enslaved women to satisfy his sexual needs. Enslaved women were particularly vulnerable in widowers’ homes. The fact that Phoebe received special treatment by Codman and a feather bed gives credence to this idea. If these women were being sexually abused by their owner, they did not have the power to stop it or to get anyone to protect them. In colonial Massachusetts, people external to the household would have been disinclined to intervene or challenge the sexual prerogatives of powerful white men – especially as it relates to their enslaved women. In the context of slavery, Codman’s unjust treatment of his enslaved workers was done with impunity. They had no one to appeal to for better treatment. Realizing they were powerless to change their owner’s behavior themselves, Codman’s slaves hoped that different owners would alleviate their suffering.16 The dilemma they faced is that they had no power to initiate their own sales to different owners. So they decided to force Codman’s hand.

Sometime in early 1749, Phoebe, Phillis, and Mark designed a plan to burn down the blacksmith shop and workhouse. Phillis claimed the arson was Mark’s idea, and he claimed Phoebe masterminded this plan. Phillis reported that Mark told the women that he wanted to live in Boston and “if all was burnt down, he did not know what Master could do without selling us.” Both he and Phoebe had enslaved spouses in Boston so they may have hoped their next owners would reside in Boston so they could be closer to them. The arsonists calculated that the destruction of the blacksmith shop and all his tools would lead to Codman’s financial devastation and force him to sell them to new owners. Although Phillis later admitted that she set the fire, she implicated Phoebe and Mark in the arson, testifying that Phoebe prepared the shavings and coals for the fire and Mark placed them in the shop for her.17 The fire, set at 1:00 a.m. on June 12, 1749, caused extensive damage. Codman’s blacksmith shop and several other nearby buildings burned. A distillery and brigantine docked nearby also caught fire, but escaped serious damage. The captain’s damages were estimated at £6,000, a near total loss for him.18

But they had grossly underestimated their owner’s financial resources: the fire did not force Codman into financial ruin as they had expected. In fact, he did not sell a single slave after that fire. Not one. Codman never figured out that his own enslaved people were responsible for it, although he may have had his suspicions. In the colonial era, fires were remarkably common and most were not the work of arsonists. Phillis, Phoebe, and Mark held the secret between them until 1755 when Phillis admitted to officials that she had committed the arson.19

Because the 1749 arson did not result in their sale as they had hoped, Phillis, Phoebe, and Mark decided to kill Codman. Consistent with a Black feminist practice of justice, murder was the last option for them to free themselves of Codman for good. Their decision to kill him suggests that they did not think he was redeemable or capable of reform. He had to die.

The conspirators, though, seem to have been spiritually conflicted about whether they could commit murder as Christians. Phillis recounted that Mark read the Bible to make sure that it was not sinful to kill a man. According to her, Mark concluded “that it was no Sin to kill him if they did not lay violent Hands on him So as to shed Blood, by sticking or stabbing or cutting his Throat.” Or so he thought. Somehow, Mark missed the dozens of biblical scriptures that forbid the shedding of blood, including the Sixth Commandment (Exodus 20:13) and the one that reads, “Cursed is anyone who kills their neighbor secretly” (Deuteronomy 27:24), which would have covered secretly killing someone with poison.20 However, most biblical statements on murder condemn the shedding of innocent blood or killing righteous people. Mark may have concluded that because Codman was neither innocent nor righteous, his murder was justifiable.21 It was Codman’s “just deserts.”

The trio decided that poison would be the best way to kill him. Quacoe’s history of poisoning is not inconsequential to this case. He may have given his wife the idea and instructed her as to which poisons to use. Phoebe, Phillis, and Mark believed it was possible to get away with killing their owner with poison because it had previously been done with success in their own neighborhood when John Salmon’s slaves killed him with poison – and got away with it. Not only were Salmon’s enslaved people never suspected of his killing but they also ultimately ended up with what the conspirators concluded were “good masters.” This gave Phoebe, Phillis, and Mark a successful poisoning model; and they may have even sought the advice of Salmon’s people. Their comment about Salmon’s people getting “good masters” after his death, suggests that freedom from slavery was not their ultimate goal, just obtaining “good masters.”22 This logic is consistent with that of other enslaved women who killed their owners. Their actions were more a moral condemnation of Codman than slavery itself.

Phoebe (possibly along with her husband, Quacoe) masterminded the poison plot. Although Mark insisted that he was nothing more than Phoebe’s and Phillis’ pawn, the evidence implicates him for being actively involved in obtaining the poison. As a male who hired his time, traveled to, and worked and lived in Boston, Mark had greater mobility and access to a wide network of enslaved people who worked for apothecaries or doctors and could readily access poison. Robbin, enslaved by Dr. William Clarke in North Boston, procured poison from his owner’s business and became a frequent supplier of arsenic to disgruntled enslaved people. Mark later admitted that he initially told Robbin “horrid lies” to get the poison, including telling him he needed it to kill three pigs. After that initial lie, Robbin did not appear to question Mark about why he needed so much arsenic. Sometimes Robbin took the ferry to Charlestown and delivered the poison to Mark and other times Mark ferried to Boston to pick it up from him. In the last month of Codman’s life, Phillis said that Robbin had come to the house in a black wig to disguise himself – obviously nervous about being identified by anyone in Charlestown. Another enslaved poison supplier was Kerr, who was enslaved to Dr. John Gibbons in Boston. Kerr typically sent the poison to the women through Phoebe’s husband, Quacoe. Phoebe had also made the trip to Boston to collect the poison directly from Kerr at least once. Even Mark had received poison from Kerr at least twice. But in June 1755, Kerr was no longer willing to provide any more arsenic because Phoebe told him that she was poisoning someone in the Codman home and that revelation made him nervous. When the arsenic proved too weak to finish Codman off, Mark obtained some lead used in pottery glazing from Essex, who was enslaved to Thomas Powers.23 What is interesting is that all of these enslaved people knew Codman was being poisoned, and most of them participated in the plot or facilitated it, passively or actively; not one of them betrayed the plot before his demise. On some level, they surely believed he deserved what was coming to him.

Although Mark procured the poison, Phoebe and Phillis administered it to Codman in his food and drink. For two years, the women fed the captain an array of poisons, including arsenic, ratsbane (rat poison), potter’s lead, and possibly raw cashews, which contain urushiol, which can be fatal if ingested before boiling. These women were quite knowledgeable about the poisons’ efficacy and potency and even how to administer each kind without detection. For example, the people who interviewed Phillis determined that she “seems to have thought [lead] was the efficient poison compared to arsenic.” She also knew a good deal about rat poison. Phillis confessed that when Mark gave her ratsbane, she discerned that it was just “only burnt allom [sic],” and not real ratsbane. She doubted its authenticity because she knew that when people took ratsbane, “they would directly swell, and Master did not swell.” Phoebe agreed with Phillis’ suspicion about the counterfeit ratsbane. The fact that both women knew the effects of rat poison suggests a high degree of familiarity with its effects in humans. The men were just as knowledgeable about poisons: Robbin had told them that arsenic should be dispensed in cold water because it would have no taste. He also instructed them that if used with “swill or Indian meal (cornmeal) … it would make ’em swell up.” Moreover, he had also advised Mark to give the vial of arsenic in two doses – directions the trio apparently failed to follow. Quacoe’s own history proved that he also knew about using poisons to harm or kill.

The women’s strategy was to kill Codman slowly, over time. Phillis claimed that when Robbin learned they had not followed his instructions, he said they were “damn’d Fools [because] we had not given Master that first Powder at two Doses, for it wou’d have killed him, and no Body would have known who hurt him, for it was enough to kill the strongest man living …”24

The larger enslaved community possessed extensive knowledge of palliative and medicinal herbs, plants, and deadly poisons. Women, in particular, learned different uses for any given plant. Collard greens, for example, could be eaten or used to cure headaches by tying the leaf to the sufferer’s head. Particular plants could have a dual function – to alleviate illness or to murder. Jimsonweed, for example, could be used to treat headaches, asthma, or dropsy, or to kill someone. In 1841, in St. Augustine, Florida, an unnamed enslaved woman along with Jake, an enslaved man, poisoned the entire Hyde family by putting the seeds of the Jimsonweed (a corruption of “Jamestown weed”) into their coffee. Every part of the Jimsonweed is extremely toxic if ingested, but especially the seeds: ingesting as little as 15–25 grams of the seeds can be fatal. The Hydes were immediately sickened after drinking their coffee, so it was obvious that their enslaved cook had poisoned them. The pair were promptly arrested. They confessed the following day and were executed shortly thereafter.25

As that case demonstrates, there was a thin line between using plants to heal and using them to kill. Practitioners could do both. Chelsea Berry found that in the West African language Igbo, the phrases for preparing medicine, practicing sorcery, and neutralizing poison are very similar – “-gwọ ọgwù (to prepare medicine), -kọ ọgwù (to practice sorcery against), and -rụ ọgwù (to neutralize effect of poison).” Among the Akan speakers, the word aduru means medicine and poison. In spite of this striking similarity of the root words and verbs in traditional West African languages, enslaved people in colonial American understood the difference. Slaveowners were equally fearful of the medicinal knowledge and practices of enslaved people. As Berry asserts, “unsanctioned medical practice” by enslaved people was extremely threatening to slaveowners, especially when used as a form of resistance. Because poisoning was done in secret, slaveholders had to live with the fear that every bite of food they took – every sip of drink – could lead to their death. That persistent, gnawing anxiety prompted some colonial authorities to legislate against enslaved people’s medicinal practices. Colonial Virginia, for one, made the “practice of medicine” by enslaved people a capital offense, punishable by death.26

The cultural knowledge African and African American medicinal practitioners held about plants, roots, herbs, and fruits must be distinguished from knowledge about deadly poisons and chemicals. Plants mostly nourish, heal or cure – although some can also kill, as demonstrated above; manufactured poisons and chemicals, by contrast, are always harmful when ingested or when in contact with the skin. Enslaved people possessed sophisticated knowledge about both categories and where they overlapped. At times, the weapons enslaved people used to poison their owners were common household cleaners and products. For example, in nineteenth-century Louisville, an enslaved girl asked a vendor for something to kill flies. The vendor was clearly accustomed to enslaved household workers procuring insecticides so her inquiry did not raise his suspicion. Unfortunately, the “flies” this girl sought to kill were her owner’s children. She mixed the insecticide with molasses and gave it to the children to drink; all three children immediately fell ill, but did not die.27

In 1859, in Richmond Virginia, an enslaved girl obtained oxalic acid from her mother who was enslaved sixty-three miles away in Fredericksburg, Virginia. Oxalic acid, then (and now) commonly used to removed laundry stains, was widely recognized as toxic and required handwashing after contact. As a product used in laundering, her possession of oxalic acid would not have raised any alarms. The young girl mixed the poison in her owner’s water and gave it to him to drink. Although when mixed with water, oxalic acid is colorless, the slaveowner noticed that it tasted acidic so he did not finish the drink, but rather, set it aside to be analyzed by a chemist. Had he finished it, he would have suffered severe gastroenteritis, vomiting, convulsions, metabolic acidosis, and kidney failure. Ingesting as little as 15–30 grams of oxalic acid can be fatal.28

Enslaved people’s access to, and shared communal knowledge of, herbs and poisons allowed them to wield a social capital and power that could be used to resist oppression, and decide whether their oppressors were maimed or died. They even chose how much or how long their owners suffered before dying. The fact that the “weapons” were often common plants grown in nature, household cleaning agents, insecticides, or raticides made it difficult to prevent these types of crimes.

In June 1755, Phoebe and Phillis increased the poison dosing. On June 13, 1755, Phillis received a tiny package that consisted of a white piece of paper that had been folded into a square and tied with twine. Inside the carefully wrapped package was nearly an ounce of white powder. She transferred the powder into a tiny vial, added water, and stored the concoction in Codman’s kitchen cupboard. For the next two weeks, she and two other people in the Codman home, Phoebe and Mark, seasoned his food and drinks with the arsenic mixture. When arsenic failed to do the job, the duo added potter’s lead to Codman’s poisonous meal seasonings.29 As the only people responsible for the family’s meals, Phoebe and Phillis possessed unlimited power to determine when and how the poison would be administered. Although Codman’s daughters lived in the home, they were not responsible for preparing the meals for their widowed father. Phoebe and Phillis poisoned Codman’s meals, snacks, drinks, and even the tea infusions he took for his lung issues. They mixed it into his barley drink, breakfast water gruel, tea, and even in his favorite luxuries, such as a chocolate drink and sago – a type of pudding made from the pith (starchy center) of the sago palm grown in Barbados. It also seems that the Codmans were not as so vigilant as they could have been: they never discovered the mysterious vial of arsenic in the kitchen cupboard, nor did they notice how the meals had changed in taste, although there was one complaint that the water gruel tasted “gritty.” On occasion, though, the Codman daughters expressed curiosity about the food, asking the cooks what the black substance was in the porringer or why the water gruel had turned yellow. The fact that none of the Codmans ever suspected that poisoning was the root of the patriarch’s health issues underscores how deeply the family trusted Phillis and Phoebe.30

Poisoning is categorized by historians as secret, or covert, slave resistance. Because it was done secretly and did not directly confront the slaveowner’s power or result in freedom, people assume this form of covert resistance also was nonviolent. It is anything but nonviolent. The poisons Phoebe and Phillis used guaranteed a violent reaction in John Codman’s body. The symptoms of arsenic poisoning include blood in the urine, stomach cramps, seizures, vomiting, diarrhea, and organ failure. The symptoms of high levels of lead toxicity include stomach pains and cramps, vomiting, muscle weakness, and seizures.31 Mark reported that his owner suffered from “a wracking Pain in his Belly.” According to reports in the local papers, Codman “was seized with an exquisite Pain in the Bowels.” In addition, he seemed to have also suffered convulsions in the last few days of his life.32 Poisoning should be recategorized as a form of armed resistance due to the extensive damage it does to the human body.

The genius of using poison to murder someone is that it can be masked as a chronic illness, as was the case with Codman. Shortly after his death, Abigail Greenleaf wrote a letter to her brother, Robert Treat Paine, who was Codman’s friend, “Capt. Codman departed this life yesterday having been ill with a cholick [sic] ever since you drank tea with him.” In the eighteenth century, colic – with stomach pain as its primary symptom – would have been the presumptive diagnosis because it was very common among adults then. It was not until five years later, in the 1760s, that physician-researcher Sir George Baker discovered that lead poisoning caused adult colic. Of course, by then John Codman was already dead.33 The fact that his symptoms could easily be mistaken for chronic illness illustrates how remarkably disciplined Phillis and Phoebe had been in the dosing amounts.

Phoebe and Phillis did not kill their owner suddenly and elicit immediate suspicion. Instead, they murdered him piecemeal over several years. If they were to get away with his murder, people needed to believe Codman had died of a chronic illness. This is the likely reason the women were so disciplined and resisted the impulse to administer the poison in larger doses. Phillis revealed that Phoebe sometimes had “put in more [poison] than she should” and that “her hand was heavy” when she added it to their owner’s food and drink. Phillis argued against using too much poison at once – likely concerned that a quick death would make people suspicious. Phoebe subsequently scaled back the poison.34 Regardless of whether Codman suffered a while or died instantly, as a white, wealthy man, his untimely death would raise questions. Unfortunately, Black women cooks were the objects of suspicion even when such people died of natural causes. In this case, however, the evidence is conclusive that Phoebe and Phillis murdered John Codman and were assisted by Mark and various other enslaved men.

When Middlesex County Coroner John Remington began his autopsy on Codman’s body the day of his death, the captain’s black lower extremities gave him pause. Remington suspected poisoning because hyperpigmentation is a sign of chronic arsenic toxicity. Upon cutting Codman’s body open, Remington reported that “some of the deadly Drug was found undissolved in his Body, which, ’tis said, was calcined Lead, such as Potters used in glazing their Ware …”35

Massachusetts coroners could hold an inquest and impanel a jury comprised of white, free, male property holders to assist in the questioning and cross-examining of witnesses. Remington formally began a coroner’s inquest on July 2, 1755. At least four members of this jury belonged to the same family: Samuel Larkin, Samuel Larkin, Jr., Thomas Larkin, and John Larkin, underscoring how much the cards were stacked against Codman’s enslaved people from the beginning. Quacoe, Phillis, Robbin, and Mark were arrested and held in the local jail. Suspicions about Mark’s culpability were confirmed when the coroner’s justices searched the property and found the potter’s lead that Mark had hidden in a wall plate, or candle sconce, in the blacksmith shop. It looked similar to the lead found in Codman’s stomach. The arsenic was never found but once the lead poison was discovered inside the blacksmith shop where Mark worked, no lie would help him escape a certain execution. The inquest jury concluded that Mark poisoned Codman; the jury assumed the women were innocent. A grand jury was convened shortly thereafter in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Middlesex County.36

Quacoe was questioned by the county justice of the peace on July 12. He stated that he had only recently found out about Mark’s efforts to acquire poison. Quacoe claimed that when he did learn of it, he told his wife not to become involved. Since his wife was the ringleader, it is unlikely that Quacoe had only recently heard about the plot – as he claimed. Given her husband’s history as a poisoner, Phoebe certainly had consulted him. But Quacoe had learned a lot from his poisoning conviction in Surinam, including how to avoid the same mistakes that had led to his discovery, conviction, and transportation. This time, he simply claimed he knew nothing about it. That strategy worked for him.37

Phillis and Mark – in that order – were then questioned by prosecutor Thaddeus Mason and Attorney General Edmund Trowbridge. Had the women feigned ignorance of the plot, they might have gotten away with murder; after all, neither had the reputation Mark had for “roguery” and defiance. But the trio’s bond had been broken the day the poison was found in Mark’s possession. Phillis, whose testimony began on July 26, fingered Mark as the mastermind and Phoebe as the primary poisoner. Phillis admitted to participating in the conspiracy, but minimized her own role, testifying that she only mixed the poison into the food a few times. She blamed Phoebe, and to a lesser extent, Mark, for the actual poisoning. Phillis told the inquest jury that she often felt “ugly” – a reference to her conscience – about what they were doing, which led her to throw away the tainted food several times instead of serving it to her owner. Phillis provided all the details about how they procured the poison, how the poison was served, and their motive. The transcript of this interrogation is the only surviving record of the women’s perspective of the crime.38

By the time he was questioned, Mark had already been named as the mastermind by Phillis and possibly Phoebe as well. Regarding Phoebe, Mark testified that she had visited him in jail “to desire me not to confess any Thing for they could not hurt me.” She might have been trying to plead with Mark to keep quiet so that they could all escape convictions and death sentences. Perhaps she calculated that without the testimony of the three of them, the authorities did not have enough evidence to convict. Regardless, Phoebe left the jail uncertain about where Mark stood and doubtful about whether he would confess. In that moment, she might have believed that she could no longer trust him because his bitterness towards her was becoming nearly palpable. She might have decided to betray Phillis and Mark to save herself from a certain execution. According to Mark, Phoebe “was an Evidence in Behalf of the king,” which means she testified against him for the prosecution. This claim was later corroborated by founding father Dr. Josiah Bartlett in his book, An Historical Sketch of Charlestown, in the County of Middlesex and Commonwealth of Massachusetts, “Phoebe, who was said to have been the most culpable, became evidence against the others.”39 She was never interrogated, arrested, indicted, tried, or convicted of the murder she masterminded.

Mark tried his best to convince officials that the women had killed their owner and that he had no foreknowledge of their plot, despite admitting that he had given them poison several times. When asked by the prosecutor why he had potter’s lead in his possession, Mark lied and said that he was testing it to “see if it would melt in our Fire.”40 When asked if he had reason to suspect that the poison he was supplying to the women was being used to poison his owner, his reply was “No other Reason than hearing Phoebe the Saturday night before master died ask Phillis, if she had given him enough, to which she replyd [sic]. Yes. I have given him enough and will stick as close to him as his shirt to his back; but who she meant I did not then know, nor untill [sic] after master died.” Mark claimed multiple times that he only learned of the plot after Codman’s death when he had confronted Phillis and she had admitted it to him. At the end of his testimony, Mark signed his deposition, an act of agency that underscored his literacy and ability to construct his own historical record.41

Using those interviews as evidence, a grand jury indicted Phillis, Mark, and Robbin on August 5, 1755. Instead of murder, Phillis was indicted for petit treason, an English common law statute 25 Edw. III c2 that dated back to 1352, that made the murder of a social superior a capital offense. The legislation was designed to protect the social hierarchies in England (and New England) by severely punishing three distinct groups – servants or slaves who killed an owner; wives who killed husbands; or a member of the clergy who killed a superior. Convictions under petit treason in colonial New England dictated that women be burned to death and men be drawn to the place of execution and there, hanged. Phillis’ indictment stated that she had acted “of Malice forethought willfully feloniously and traiterously [sic] poison kill & murder the said John Codman … against the Peace of the said Lord the king [and] his Crown & Dignity.” Robbin and Mark were named as accessories. The indictment stated the men “did traiterously [sic] advise & incite [and] procure & abet the said Phillis to do and commit the said Treason & Murder.” Mark was charged only as an accessory to Phillis’ petit treason. Despite her prominent role, Phoebe was not indicted, a fact that gives credence to the idea that she may have betrayed her co-conspirators. Despite their prior confessions during the coroner’s inquest, both Phillis and Mark pleaded not guilty at their arraignments. For his part, Robbin’s charges seem to have been dropped by the time Phillis and Mark were arraigned.42

The judicial system that enslaved people faced in colonial Massachusetts, a society with slaves, was different from what they might have experienced in slave societies. For one, they were not subject to separate, slave courts. Enslaved people had their cases heard in the Superior Court of Judicature. Based on the principles in the Magna Carta, colonial Massachusetts prohibited death sentences without due process for anyone, including enslaved people. Enslaved people also enjoyed the right to a grand jury, legal counsel, legal challenges, and juries. They had the right have their indictments read to them and to testify in court, except against whites.

The pair’s trial commenced on August 6, 1755, in the Superior Court of Judicature, Court of Assize, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Chief Justice Stephen Sewall and Associate Justices Benjamin Lynde, Jr., John Cushing, and Chambers Russell presided over the trial.43 The historical record is silent on whether these justices owned enslaved people. Neither defendant was provided with a member of clergy to counsel them, owing to an English law that dictated that those charged with intentional and premeditated murder would be denied that right. More than twenty witnesses were subpoenaed to testify for the prosecution against Phillis and Mark, including six Codman children. The rest of the Codman slaves, including Pompey, Thomas, Cuffee, and Scipio also received subpoenas. Multiple other enslaved people also testified, including Essex, the servant of Thomas Powers, a person enslaved to Dr. Rand, Dinah (who belonged to Richard Foster), the servants of John Gibbins and John White. There is no extant record of their testimonies. Interestingly, Phoebe received no subpoena despite her extensive and intimate knowledge of the plot. White people sometimes served as proxy witnesses for enslaved witnesses, and testified in court about what enslaved people told them directly. The long list of prosecution witnesses was insurmountable for Phillis and Mark’s defense.44

Phillis and Mark were convicted of their charges of petit treason and sentenced to death. Their death warrants, signed by Richard Foster, the Middlesex sheriff, scheduled their executions for September 18, 1755, between 1:00 and 5:00 p.m. The death warrant for Phillis indicated that she was “to be drawn from our goal [sic] … to the place of Execution & there be burnt to Death.” Phillis’ sentence was exceedingly harsh, but it was the prescribed sentence for petit treason. Mark’s death warrant stated that he was “to be drawn from our goal [sic] … to the place of Execution & hanged up by the Neck until he be dead.” “To be drawn” meant to be dragged by a horse across the ground. Although it was typical for men to be drawn to a place of execution in the colonial era, the practice was rarely used on women. In that way, as a woman, Phillis was defeminized and subjected to a level of public humiliation typically reserved for men. While being dragged, there would be no way to stop her dress from going up (women, without exception wore dresses in colonial America), exposing her private areas. Massachusetts changed the mode of women’s punishment for petit treason from burning to hanging in 1777 and ended charges under the petit treason statute altogether in 1790 – too late to benefit Phillis.45 Phoebe was condemned to be transported to the West Indies for her role in the murder.

On the eve of his execution, Mark wrote a dying declaration (Figure 1.2). His is one of just a few surviving dying declarations written by enslaved people in the colonial era. By the time he wrote his declaration, he was consumed with resentment that Phoebe had not received her “just deserts,” so he exposed her true character to white Charlestowners. He expressed contrition and regret and admitted his role in the poisoning death, but insisted that the women had “enticed” him to get the poison. Referring to the 1749 arson, Mark claimed that he had nothing to do with it, claiming to have been sick in bed when the shop was set afire. He accused Phoebe of thievery while the shop burned: she “wickedly stole some of the cloaths [sic], thrown of the Window to be sav’d [sic] … and to my certain Knowledge, she was a great Thief …” Mark continued, “She stole Money from my Master … One Hundred Pounds in Money, Part of which, I believe to be in Phoebe’s Sisters Hands …” There is no way to determine if his accusation is true or merely a final ploy to get Phoebe in trouble. In this version – his last – Mark provided details different from those he had previously shared with the coroner’s inquest jury about the days preceding Codman’s death. In his dying declaration, he claimed that when one of the other enslaved people in the home had asked Phoebe how their owner was faring on his deathbed, she referred to him as “the old dog” and promised that she would “stick as close to him as his Shirt to his Back and not only so, but she would cut down the Old Tree, and then would hew off the Branches” – a chilling reference to killing Codman and then his children. Mark had previously testified that Phillis was the one who made the reference to sticking as close to Codman as his shirt on his back, but later attributed those words to Phoebe. He also recounted that although Phoebe had sat at Codman’s bedside with his children as he lay dying, behind his back she celebrated his impending death and mocked his suffering. Mark claimed that as their owner lay dying, Thomas and Phoebe gleefully rejoiced at his impending death, “when [he was] in the bitter Pangs of Death.” Mark alleged that after having witnessed Codman’s convulsions Phoebe “got to dancing and mocking master & shaking herself & acting as master did in the Bed.” He claimed that Thomas reportedly told the others that he did not care what happened to their owner and “hop’d he wou’d never get up again.” Mark painted Phoebe as a conniving, heartless thief and monster. He also implicated Quacoe, insisting he was “as knowing in this Affair as I was.”46 Mark’s dying accusations had no effect: Phoebe was never indicted for Codman’s death and there is no record of her having been transported from colonial Massachusetts, much less out of British North America. She got away with murder. Testifying against one’s fellow conspirators is the only way Black women could proactively escape executions in colonial America.

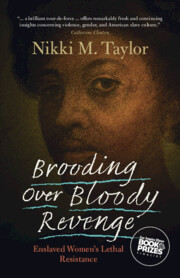

Figure 1.2 The Last and Dying Words of Mark (1755)

As Mark’s dying declaration reveals, he still felt deep regret and harbored resentment towards Phoebe on the eve of his death. For Phoebe’s part, by turning state’s evidence on her co-conspirators, she had escaped the death penalty and, instead, was condemned to transportation. By contrast, Phillis accepted her fate, admitted her role in the crime, repented for it before man and God, and apparently felt peace within herself before her execution. Unlike Mark, she made no bitter pronouncements, failed to implicate anyone else, and refrained from accusing Phoebe of additional crimes. The difference between how Mark and Phillis responded is that Phillis admitted her guilt and was resigned to accepting the consequences of her actions. On September 18, 1755, Phillis and Mark were drawn and executed at the gallows in Cambridge, not far from Harvard College (now University). According to the Boston Gazette, their executions were “attended by the greatest Number of Spectators ever known on such an Occasion.”47

Britain’s 1752 “Murder Act” denied convicted murderers the right to a church burial unless they had received a post-mortem punishment. The irony of a “post-mortem” punishment is that the offender was not alive to experience it; instead, the person’s family and community witnessed the horrors of the desecration of their body. Hanging a corpse “in chains,” whereby a corpse was placed in a gibbet, or cagelike structure, and displayed in public as a deterrent to others, had been popular in England, but its usage peaked in the 1740s. After the passage of the Murder Act, anatomical dissection was the most common post-mortem punishment in England until 1832; by contrast, gibbeting was less common. Britain’s North American colonies only rarely followed the mandate for post-mortem punishment. When they did, they preferred gibbeting to dissection. However, in the English Caribbean, gibbeting was used as a form of torment/execution, with the convicted person being placed in chains while still alive.48

After Mark was hanged to death, his body was prepared for an impromptu gibbeting. Although he had not been officially condemned to a post-mortem punishment, local officials made the decision to hang Mark’s body in chains, possibly to satisfy local demands. Gibbeting was a gendered practice limited to men; consequently, Phillis escaped this gruesome post-mortem punishment. After his hanging death, Mark’s body was measured and fitted for a gibbet. The gibbet was then quickly constructed. Once the body was placed in the irons, the gibbet would then be raised thirty feet or more above ground – too high for anyone to remove the corpse. Customarily, bodies were hung in chains as close as possible to the actual crime scene. Popular attractions or spectacles for locals and travelers alike, gibbets were placed at crossroads or popular landmarks to maximize the number of people who saw them. Mark’s body was hung in chains at the Charlestown Common (about ten yards from the gallows) or town square.49

Locals intended to keep Mark’s body hanging in gibbets until “the elements or the ravages of birds of prey” would pick all the flesh from his bones. For those who lived near the gibbeted body, the stench of a decaying corpse could be unbearable, as were the rodents, scavenging birds, and bugs it attracted. There was no specified time frame that bodies would hang in gibbets. Many, like Mark, remained for decades and became local landmarks.50 The remains of Mark’s body hung in that gibbet for at least twenty years as a chilling local landmark. Dr. Caleb Rea, a traveler who lodged near Mark’s gibbet in 1758, remarked that the “skin was but very little broken” even after a few years. Paul Revere, recounting the events of his famous ride on April 18, 1775, to alert the American colonists that the Redcoats were approaching, referenced that he was nearly overtaken by them “where Mark was hung in chains.”51 It is not clear when Mark’s corpse was ultimately removed. By the mid-eighteenth century, British society – which had invented the grisly practice – found the prolonged public display of decaying and dismembered bodies for decades distasteful, if not also incomprehensible. Gibbeting also became increasingly less popular in the mainland North American colonies, eventually fading as a practice after the American Revolution.

On the same day Mark was hanged, Phillis was burned at the stake. The difference between hers and Mark’s modes of execution is a reminder that Phillis was considered one of the masterminds and far more dangerous than him. Being burned at the stake, or burned alive, was typically reserved for the most vicious and unrepentant murderers in colonial America and beyond. Rarely was it ever done to women. Even the women convicted in the Salem Witch Trials were not burned at the stake like Phillis. In spite of the prolonged gibbeting of his body, Mark at least died instantly; Phillis, on the other hand, was tortured slowly. Burning someone at the stake was particularly sadistic and designed to inflict intense suffering. Historian Quito Swan, who wrote about Sally Bassett’s burning in Bermuda in 1730, reminds us of the visceral nature of such a scene of horror. It would have affected the senses of those who witnessed it. Phillis’ unnatural wails and screams of anguish would have pierced the air – echoing from the Common through Charlestown’s streets, alleys, and homes. They would have been impossible to miss – or ignore – in a town that size, even for those who did not attend the event. Those present would have witnessed Phillis’ physical response to the pain of fire destroying her flesh: her body must have twisted and convulsed in agony. Spectators would have seen her flesh melt from her bones as the flames consumed her. The combination of smoke and burning flesh, hair, and bones would have been noxious to smell. We will never know whether the spectators were aghast or covered their eyes and noses. Did they wince in horror or revel at watching her slowly burn to death? Did they cheer or pray for her as her soul departed?52 We will never know. What we do know is that Phillis’ mode of execution says more about the inhumanity of the society in which she lived as an enslaved woman than it does about her humanity or final act of resistance.

Despite the fact that Phoebe and Phillis conceived, planned, and led this act of resistance, prominent historians have reduced them to background players in Mark’s plot.53 The reality is that Mark was charged and convicted of being only an accessory in Phillis’ plan. Mark was given the mantle of leadership by historians because he was male and some are incapable of imagining enslaved women as leaders of slave revolts. In the historians’ defense, Mark’s gender and literacy did make him loom larger in the historical record. But the inability to see the outsized role the women played corrupts the history. The Codman case illustrates Black women’s capacity to organize and execute a lethal collective action against an abusive slaveowner – and in Phoebe’s case, escape the consequences.

Every aspect of this case reflects the Black feminist practice of justice. Codman’s enslaved people initially wanted more humane and just owners. Their arson conspiracy did not result in their sale, as they had wished. When that plan failed, Phoebe and Phillis handed Codman a death sentence if for nothing else than enslaving, abusing, and denying his enslaved people their humanity. Murder was their last best option to remove themselves from his authority. The conspirators were remarkably patient, killing him slowly over six years. They delighted in his suffering and privately mocked him at his weakest moments. To these women, prolonged physical suffering was an essential part of Codman’s “just deserts.” This is what they felt he deserved.

…

Phillis was only the second enslaved woman executed this way in the colony of Massachusetts. (Maria, who was burned at the stake in Boston in 1681 for arson, was the first.) According to the ESPY database of executions in the United States, only twelve Black women were burned at the stake during the entire slave era. The other enslaved women sentenced to be burned alive were either convicted of arson or poisoning murders. Enslaved men were, by contrast, far more likely to be burned to death during the age of slavery. In the colonial era alone, thirty-two Black men met that fate.54

Phoebe and Phillis are not the only enslaved women convicted of using poison to kill or attempt to kill their owners in the long history of American slavery. In January 1751, and across the Charles River, Phillis Hammond was accused of a poisoning death. That Phillis was a sixteen-year-old girl owned by a prominent apothecary, Dr. John Greenleaf, and his wife, Priscilla. Priscilla had given birth to three children, all of whom died as toddlers, within a short span of time. The death of the last Greenleaf child – their only son, John Jr. – caused them to believe that it was not fate playing a cruel joke, but a human culprit who had prematurely ended their children’s lives. Within days, Phillis was arrested for the death of the eleven-month-old John. The Boston Evening Post reported that he had been killed by “arsenic or ratsbane.” The paper noted that Phillis also confessed to having previously poisoned the Greenleafs’ fifteen-month-old daughter. Young Phillis was hanged in May 1751 for those crimes.55 Certainly, Phoebe, Phillis, and Mark heard about that story and may even have personally known young Phillis, given how much time they spent in Boston. They also would have known that she was hanged for the alleged crime. The fact that they knew the harsh consequences of poisoning in colonial Boston and still persisted with their plan underscores how much they were willing to risk to ensure Codman’s death.

The Boston area poisoners were not alone. In the colonial era, hundreds of enslaved Black women were convicted of and executed for poisoning their owners. For example, on January 10, 1738, Bess, an enslaved woman owned by John Beall of Prince George’s County, Maryland, was accused of his attempted murder. Poison was her weapon of choice. Bess was tried, convicted, and sentenced to death in March and hanged for that crime on June 7, 1738.56 On March 20, 1738, Judy of Queen Anne’s County, Maryland, was executed for the poisoning death of her overseer. In 1747, in Prince George County, Virginia, Abbe was accused of poisoning her owner, Dr. James Tyrie. She escaped a certain execution by hanging herself in her jail cell. In Charles County, Maryland, in July 1755 – the same year as Codman’s death – Jeremiah Chase’s enslaved worker, Jenny, was tried, convicted, and executed for conspiracy to murder him by poison. In Anne Arundel County, Maryland, Tida was accused of attempting to poison her owner, Ephraim Glover, on February 1, 1757. She was executed for the alleged attempt on April 7 that year. An unnamed, enslaved South Carolina woman owned by a Mr. Fickling was hanged on January 14, 1761, for poisoning him. In Calvert County, Maryland, two enslaved people – Rachel, owned by John Hamilton, and Samuel, owned by William Hickman, were accused of the attempted poisoning of Mrs. Smith “some years ago.” They were both hanged for the basis of that suspicion on October 15, 1761. Curiously, in that same county, three years later, three additional enslaved people were convicted of the same crime of attempted poisoning against what may have been the same victim, a Mrs. Smith and her husband, William Smith. This time, Betty, Sambo, and Joe were executed on June 20, 1764, for the alleged attempted poisoning. In 1772, an enslaved woman named Judith Harrison was hanged for poisoning in Brunswick County, Virginia.57

In the early national era in Nash County, North Carolina, an enslaved woman named Beck was tried and convicted of poisoning the men in the Taylor family in 1793, including Henry Taylor and his two sons, Henry Jr. and Samuel. In North Carolina in 1800, Sue (owned by John Cates) was convicted of poisoning William Cooke and his family.

On January 28, 1803, Chastity Lawson was hanged for poisoning her owners in Virginia Beach. On February 28, 1806, Fanny Goode was hanged for poisoning in Charlotte, Virginia. In the antebellum era in South Carolina, Eve was convicted of administering poison to her owners in 1829. Three years later, Renah and Fanny Dawson were executed for the crime in Prince Edward County, Virginia, on January 5. Later that same year, 1832, Lucy, an enslaved woman of the Bouligny family in Jefferson County, Louisiana, was hanged for poisoning. Aurelia Chase was hanged on December 20, 1833, in Baltimore for the same crime. On January 12, 1849, two enslaved women in Brunswick, Virginia, Eliza Griffin and Roberta Ezell, were hanged for poisoning. In 1851, Mily Fox was executed in Louisiana. In September 1854 in Thibodaux, Louisiana, an enslaved woman was accused of putting arsenic in her owner’s food. Mr. Rawlings, her owner, suspected it had been poisoned so he allegedly gave the food to a dog, which killed the animal within minutes. Rawlings then allegedly consulted a chemist who confirmed that arsenic was in the food. In 1857, an enslaved girl tried to poison the entire slave patrol of New Kent County, Virginia, by pouring muriatic acid in a liquor decanter kept for their entertainment. She confessed and was convicted of the crime.58

In 1859, Lucy, an enslaved woman belonging to Araminta Moxley in Prince William County, Virginia, who reputedly was also the daughter of Moxley’s late husband, Gilbert (1778–1811), poisoned the entire family with arsenic. Araminta died immediately and Lucy was convicted and executed for her murder on April 22, 1859. Lucy cited poor treatment as her motive. On September 7, 1860, in Franklin County, Kentucky, Frances Berry was hanged for the crime of poisoning. Later that year, in Louisville, Kentucky, Watt Clements reported that five of his enslaved people, including two women, had put poison in his family’s milk.59

One of the most interesting instances of enslaved people’s use of poison as a weapon against their oppressors in American history was when it was used in revolt plots. In May 1805, whites in Wayne County, North Carolina, uncovered a widespread plan to revolt. Having been inspired by the Haitian Revolution, the conspirators planned to use poison to kill all the powerful white men in the region. After those men were dead, the plan was to subdue and enslave the remaining whites. Dozens of enslaved people were implicated in this plot; however, the very first person to be convicted of it was an enslaved woman who was accused of poisoning her owners and two others. Like Phillis, she was burned alive. One observer noted that several enslaved men were hanged, and one was “pilloried, whipped, nailed, and his ears cut off, on the same day,” for their roles in the plot.60

It is nearly impossible to know with certainty if these other enslaved women actually poisoned their owners or were just suspected of it. For enslaved people, the result was the same – execution. Often the only information historians have about these poisoning cases is the nature of the conviction, name, and dates of execution. Unlike the Phoebe and Phillis case, only a few of these other incidents have surviving records of their trials, court testimonies, or “confessions.”

Surely, all manner of unexplained or sudden sicknesses before the nineteenth century were attributed to “poisoning” and blamed on the enslaved people who prepared the food. In fact, even food poisoning, which is very common now and even more so in an era before refrigeration (1851) and pasteurization (1862), likely would have been blamed on enslaved people. David V. Baker estimated that as many as one-third of the enslaved women executed for poisoning had not actually poisoned anyone, but the cases stemmed from foodborne illnesses, instead. For example, in Orange County, Virginia, in January 1746, an enslaved woman named Eve was convicted of the murder of her owner, Peter Montague, who became gravely ill in August 1745 and finally died on December 27 that year. Before dying, Montague indicated that he had fallen ill in August after he drank some milk. He came to suspect that the milk had been poisoned by Eve. With milk at the center of the case, many doubts are raised about whether Montague had, in fact, been poisoned at all. Before the pasteurization process was developed in 1862, consumption of raw or unpasteurized milk was extremely dangerous because it contains a harmful bacteria cocktail, including Brucella, Campylobacter, E. Coli, Listeria, Salmonella, and Cryptosporidium. There is a possibility that one or several of these bacteria caused Montague’s extended illness, suffering, and death. Regardless, like Phillis, Eve was drawn to the site of her execution and burned at the stake for a murder, real or imagined.61

The vast majority of those charged with poisoning before 1865 were enslaved people. On a micro level, 100 percent of those convicted of poisoning in antebellum Virginia were Black. Consequently, poisoning accusations became associated with African Americans. Besides being raced, poisoning accusations were also gendered: Black men were more likely than women to be convicted of using poison to murder during the slave era. In fact, 71 percent of Blacks convicted and executed for this crime were male, contrary to the popular belief that women were the ones who poisoned the food.62 In colonial Maryland between 1726 and 1775, 67 percent of the enslaved people convicted of poisoning were males and just 33 percent were women. Similarly, in antebellum Virginia, Black men comprised 60 percent of those executed for poisoning; and 40 percent were Black women. In South Carolina, between 1824 and 1864, nine enslaved men and two women were arrested for poisoning.63 Hence, although poisoning is one of the most prevalent methods enslaved women used to murder their owners and oppressors, men used it as a deadly weapon more often. Women only account for one-third of all executions of enslaved people for poisoning before the Civil War. Although the death penalty was not applied evenly for men and women in every state, the data does suggest men were more likely to get caught at the very least.

Regardless, along with arson, poison was the most common weapon enslaved women used to commit murder and the top crime for which they were convicted and sentenced to death.64

In the end, the secret, powerful, and deadly weapon of poison is the one thing that terrified slaveowners daily. The more cruel, violent, and abusive ones had good reason to fear that every bite of food or sip of drink could lead to their untimely demise through an intentional act of revenge. And sometimes revenge was served cold by enslaved women.