LEARNING OBJECTIVES

-

Understand the basic nature of the concepts of spirituality and religion and their relevance to clinical practice in psychiatry

-

Be aware of the key arguments in the current debate concerning spirituality and religion in clinical practice and the corresponding implications for good psychiatric practice

-

Know how to take a spiritual history

Clinical psychiatry has to take account of a wide variety of beliefs, behaviours and values that influence the self-understanding of the patient. This is necessary both to enable an in-depth understanding by the clinician of the patient’s personal history and mental state, and to inform management and planning for recovery. For many people spirituality and/or religion are particularly important as a fundamental framework within which their self-understanding is shaped and many patients express a wish to be able to talk about such matters with the mental health professionals providing their clinical care.

Recent years have brought an increasing appreciation of the importance of spirituality and religion in clinical practice (Reference Cook, Powell and SimsCook 2009a) and a growing research evidence base to support this (Reference KoenigKoenig 2005), but there has also been much debate about this evidence and its implications for good clinical practice (Reference Cook and CookCook 2013a). There is reason to believe that the beliefs and attitudes of mental health professionals are often different from those of patients and that this presents scope for misunderstanding (Reference CookCook 2011a). There is therefore a need for psychiatrists to be well informed about the relevance of spirituality and religion to clinical practice, the associated evidence base and the ongoing professional debate, in order that they may both meet the aspirations and needs of their patients and work according to accepted standards of good psychiatric practice.

The evidence base

It is beyond the remit of this article to offer a review of an evidence base that now spans many thousands of quantitative research studies, let alone qualitative studies and clinical articles. Although there is a general consensus that the research evidence suggests spirituality and religion to be beneficial for mental well-being, it is important to note that there is still fierce controversy and scope for alternative interpretations of it (Reference SloanSloan 2006). Undoubtedly, much research has been of poor quality and there is need for more rigorous methodology, but there have also been significant studies of good design. Critical systematic reviews have been undertaken that take the key methodological considerations into account, notably by Harold Koenig and his colleagues (Reference Koenig, McCullough and LarsonKoenig 2001, Reference Koenig2009, Reference Koenig, King and Carson2012).

The work of Richard Sloan and others provides a useful summary of the main counterarguments employed in the debate in the USA (Reference Sloan, Bagiella and PowellSloan 1999, Reference Sloan2006). These include not only scientific critique of the methodology, design and interpretation of much of the quantitative research in this field, but also concerns that focus more on ethical issues and professional practice. Much of the UK debate has also focused on concerns about good practice and the potential for boundary violations (Reference Cook and CookCook 2013a; Reference Poole and HiggoPoole 2011).

There is also debate about the strength and nature of the relationship between religion/spirituality and mental health. Smith et al (2003), in a review of 147 studies of religiousness and depression, found only a weak correlation (r = −0.096) between religiousness and fewer symptoms of depression. Reference Hackney and SandersHackney & Sanders (2003), in a meta-analysis of 34 studies, found that it was possible to come to different conclusions concerning the relationship between religiosity and mental health. Although their overall correlation between the two was positive (r = 0.10), they were able to find support for overall positive and negative correlations, and also for a lack of any relationship between religiosity and mental health, depending on the definitions employed. In particular, institutional definitions of religiosity (focusing on the social and behavioural aspects of religion, such as attendance at religious services and ritual prayer) tended to produce weak or negative correlations.

Definitions

Spirituality

Spirituality is not easy to define. There are many definitions and little agreement or consensus as to exactly how the concept should best be understood in the healthcare context. However, some definitions are more inclusive than others, and a broad approach that has been adopted in the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Position Statement Recommendations for Psychiatrists on Spirituality and Religion (Reference CookCook 2013b) provides a helpful starting point for our discussion here (Box 1).

BOX 1 Definition of spirituality

Spirituality is:

‘a distinctive, potentially creative, and universal dimension of human experience arising both within the inner subjective awareness of individuals and within communities, social groups and traditions. It may be experienced as a relationship with that which is intimately “inner”, immanent and personal, within the self and others, and/or as relationship with that which is wholly “other”, transcendent and beyond the self. It is experienced as being of fundamental or ultimate importance and is thus concerned with matters of meaning and purpose in life, truth, and values.’

Although this definition is somewhat imprecise and difficult to operationalise for research, it does incorporate the breadth of the ongoing debate. It also incorporates some of the key ambiguities, and avoids oversimplification. Essentially,

-

spirituality is a personal, individual and subjective affair, but is also concerned with relationship with others, shared beliefs and traditions, and a wider reality

-

spirituality is concerned with both transcendence (a relationship to that which is above, beyond and greater) and immanence (an awareness of present objective reality)

-

spirituality is concerned with meaning and purpose in life, and with things that are most valued; although not explicit in the definition, it is thus also concerned with loss of meaning and purpose, or with circumstances and events that impinge adversely on the things in life that are most valued.

Religion

It has been suggested that religion is easier to define than spirituality, a suggestion that those engaged in the academic study of religion will immediately recognise as fallacious. Definitions are variously concerned with beliefs and practices related to the sacred, and with individual, institutional and social expressions of these beliefs and practices. However, religiosity (how religious a person is) is a much easier variable to operationalise for research, and spirituality is easily confounded with psychological variables (Reference KoenigKoenig 2008). It is easier also to enquire about religion in the clinical context, as people usually know whether or not they identify with a particular religion, and can give answers to simple questions about attendance at places of worship, religious beliefs and devotional practices. Spirituality is often contrasted with religion as being more concerned with the personal, subjective and experiential, whereas religion is portrayed as more ritualised, dogmatic and institutional. This is an oversimplification.

Key positions in relation to religion and spirituality

In the contemporary context in Western society (and to a variable degree in other societies also) people may identify with any of a number of key positions:

-

spiritual and religious

-

spiritual but not religious

-

religious but not spiritual

-

neither spiritual nor religious.

People who are spiritual and religious generally find it difficult to separate their spirituality from their religious faith. The former is an expression of the latter, and vice versa. People who are spiritual but not religious, however, generally eschew identification with religious traditions and have a more or less coherent sense of their own spirituality that is not dependent on such traditions, even if it may draw on elements of them. Within this group would be included many so-called ‘new age’ forms of spirituality, as well as others that draw on elements of various religions in an individual way, while not identifying with any of them. People who are religious but not spiritual would see their religious tradition as important, but would not identify themselves as being ‘spiritual’ (whatever that might mean to them). Finally, some people see themselves as neither spiritual nor religious, preferring to eschew both traditional religion and also newer forms of spirituality unconnected with religion.

In practice, few people seem to identify themselves as religious but not spiritual, and the ‘spiritual but not religious’ category appears to be popular and growing. Spirituality thus functions as a more inclusive category than religion, and many agnostics and atheists may be found who would identify themselves with the ‘spiritual but not religious’ category. For many, spirituality is seen as a universal category, and it is suggested that all human beings experience a spiritual dimension to life. However, some atheists and agnostics find the category of spirituality unhelpful. Finding meaning and purpose in life in other ways, they do not see the need to identify things as ‘spiritual’, and perhaps also find the term spirituality too redolent of religion. This raises the very valid question as to whether or not the term ‘spirituality’ is really required at all. Perhaps it is only necessary to enquire about people’s beliefs, values, practices and relationships. However, to adopt this approach would not seem helpful for the many people to whom spirituality is deeply important. It is therefore necessary to make sensitive enquiry as to what people understand by the word ‘spirituality’, and whether or not it is important to them. This is just as important when it is discovered that ‘spirituality’ is perceived as deeply unhelpful and not to be discussed, as it is when it is discovered that spirituality is perceived as central to life and a key part of an overall understanding of both life and illness.

Clinical practice

In any new clinical encounter, the psychiatrist and patient will not know in advance whether they share a spiritual/religious perspective, or whether they have significant differences about such matters and what the nature and significance of any differences between them might be. It is therefore an important clinical task to manage such encounters with a respectful openness to the expectations and values of the other person.

In Recommendations for Psychiatrists on Spirituality and Religion (Reference CookCook 2013b), it is suggested that the stance of patients and colleagues, and indeed the psychiatrist’s own stance on such matters, may reasonably be expected to fall into one of the following categories:

-

identification with a particular social or historical tradition (or traditions)

-

adoption of a personally defined, or personal but undefined, spirituality

-

disinterest

-

antagonism.

Any questions that are asked, or statements made, at an initial encounter with a new patient or colleague should therefore be worded in such a way as to communicate respect equally for any/all of these positions. For example, ‘Would you identify yourself as a spiritual or religious person?’ allows a spectrum of responses, from a definite ‘Yes’ through to a definite ‘No’, with various degrees of commitment in between. On the other hand, ‘How is spirituality important to you?’ might well be taken to imply that spirituality should be understood as important, and that a positive response is expected. This might create unhelpful barriers to further communication or be the cause of misunderstanding.

Boundaries

While the relevance of spirituality/religion to clinical practice makes this an appropriate area of clinical enquiry, it is also clear that there are important boundaries to be observed. Among these are the boundaries of specialist expertise, boundaries between the secular and religious, and the boundary between personal and professional values (Reference Cook and CookCook 2013a).

The boundaries of professional knowledge and expertise

Psychiatrists have variable knowledge of spiritual and religious matters. On the one hand, they need to be better informed about such things. On the other hand, it is important that they should not profess or imagine a level and kind of expertise that they do not have. Even for those clinicians who do know a lot about such matters, it is important to recognise that the patient is the expert on their own beliefs and practices. Although much may be known about (for example) Islam as a major world religion, it should not be assumed that any particular patient adopts more widely assumed norms, not to mention that most of the world’s faith traditions incorporate a diversity of major and/or minor variations (such as the division between Sunni and Shiite in the case of Islam).

The boundary between the secular and religious

The current debate suggests that there is a divergence of views on how the boundary between secular and religious should be managed in clinical practice. There may be some agreement that a safe, neutral space is needed in which matters of spirituality and religion can be explored when necessary, but it is far from clear that the secular domain provides such a space. Many religious people find ‘secular’ views and norms to be deeply biased against the religious point of view, and an overemphasis on secular norms can make it seem as though they may not talk about religious or spiritual matters (Reference Cook, Powell and SimsCook 2011b).

The boundary between personal and professional values

The boundary between personal and professional values should always be acknowledged, at least in the mind of the clinician, if not in the course of explicit conversation with colleagues and patients. General Medical Council guidance makes clear that doctors should not normally discuss their beliefs with patients, unless directly relevant to patient care (GMC 2013). Obviously, any such discussion that does take place needs to make clear what is a personal view and what is a professional view, and any kind of proselytising (implicitly or otherwise) is completely unacceptable.

Good clinical practice

The GMC guidance also makes clear that patients should not be put under pressure to discuss or justify their beliefs. This may be difficult if the beliefs in question relate closely to the psychopathology, or are directly relevant to treatment or adherence, and must be handled with extreme sensitivity. A good rule, in case of doubt, would be to discuss practice with a supervisor or peer, perhaps as part of a case discussion in support of appraisal and revalidation. Careful documentation of practice, and of such discussions that are had, or of reasons for pursuing or not pursuing enquiry further, will also be important.

Recommendations for Psychiatrists on Spirituality and Religion provides further guidance intended to clarify and affirm the boundaries of good practice (Reference CookCook 2013b). This includes recommendations concerning assessment, the need to respect the views of patients, carers and colleagues, the need for appropriate organisational policies, and the importance of addressing spirituality/religion in psychiatric training and in continuing professional development. Importantly, the need for willingness to work with leaders of faith communities, chaplains, pastoral workers and others is affirmed.

Assessment

A variety of structured approaches have been devised as instruments for screening or assessment of spiritual well-being and spiritual needs, some of which have been designed primarily for clinical use, and others with research in mind. Assessment of spirituality, spiritual well-being or spiritual needs does not necessarily require the use of any of these instruments, and many clinicians devise their own form of enquiry. Such enquiry might include questions implicitly concerned with spiritual issues (e.g. ‘What motivates you and gives you reason for living?’) or else might explicitly address the matter at hand (e.g. ‘Do you have any spiritual or religious beliefs that are important to you?’). Such questions need not be time consuming (contrary to assertions that clinicians do not have time for such things (Reference SloanSloan 2006)) and are often helpful in establishing whether or not this might be a useful focus for further enquiry or, conversely, something that a patient would prefer not to discuss. Reference Culliford, Eagger, Cook, Powell and SimsCulliford & Eagger (2009) have suggested that the initial brief questions that might usefully be asked in spiritual history taking include those about ‘What helps you most when things are difficult?’ and those about spiritual identity (‘Do you think of yourself as being either religious or spiritual?’).

Among the more structured approaches there is a bewildering variety of acronyms with similar and overlapping concerns. The general concern here seems to be with clinical utility, and often these instruments seem to be more useful as a mnemonic than in terms of any particular form of words that they offer. For example, ‘HOPE’ (Reference Anandarajah and HightAnandarajah 2001) helpfully reminds the clinician to ask about:

-

sources of Hope, meaning, comfort, strength, peace, love and connection

-

Organised religion

-

Personal spirituality and Practices

-

Effects on medical (psychiatric) care and End of life issues.

Similarly, ‘SPIRIT’ (Reference MaugansMaugans 1996) provides a reminder to enquire about:

-

Spiritual belief System

-

Personal spirituality

-

Integration and Involvement in a spiritual community

-

Ritualised practices and Restrictions

-

Implications for medical care

-

Terminal events planning (advance directives).

The authors of both of these papers provide some sample questions to aid spiritual history-taking according to their respective formulae.

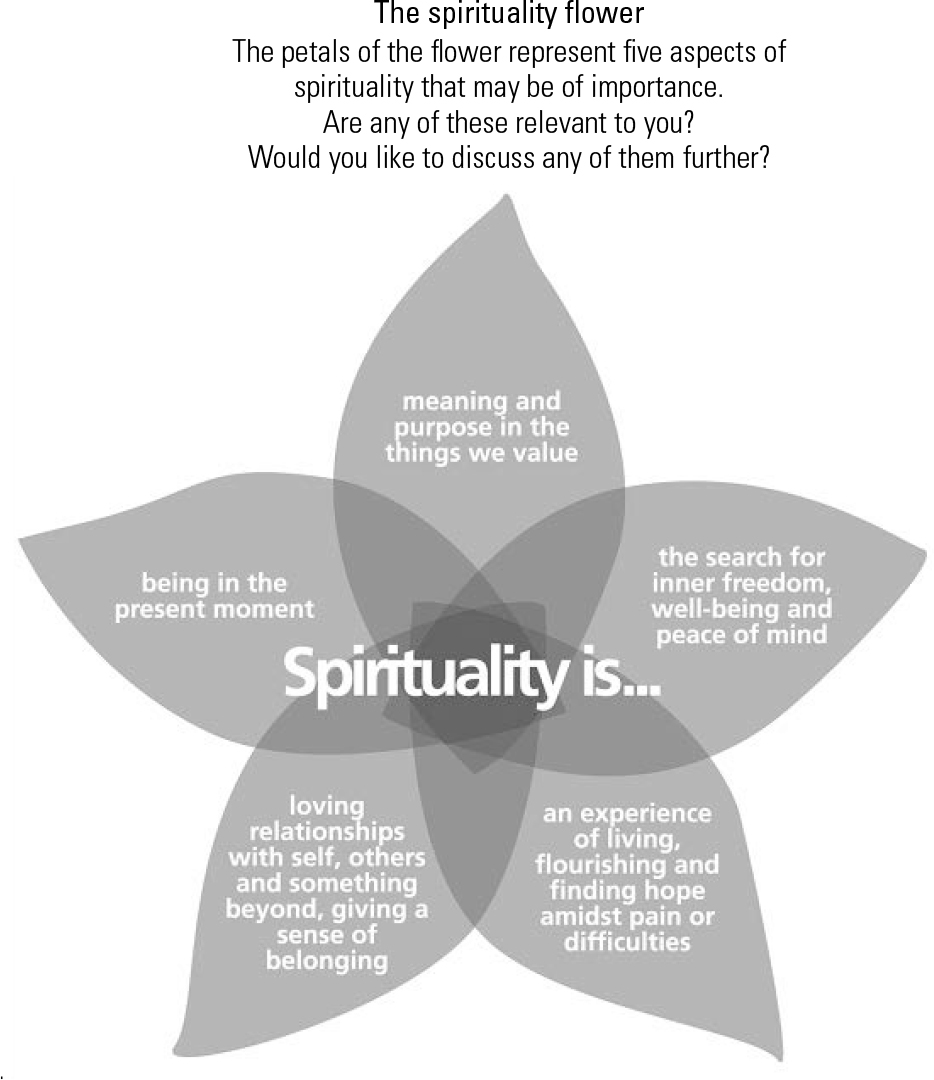

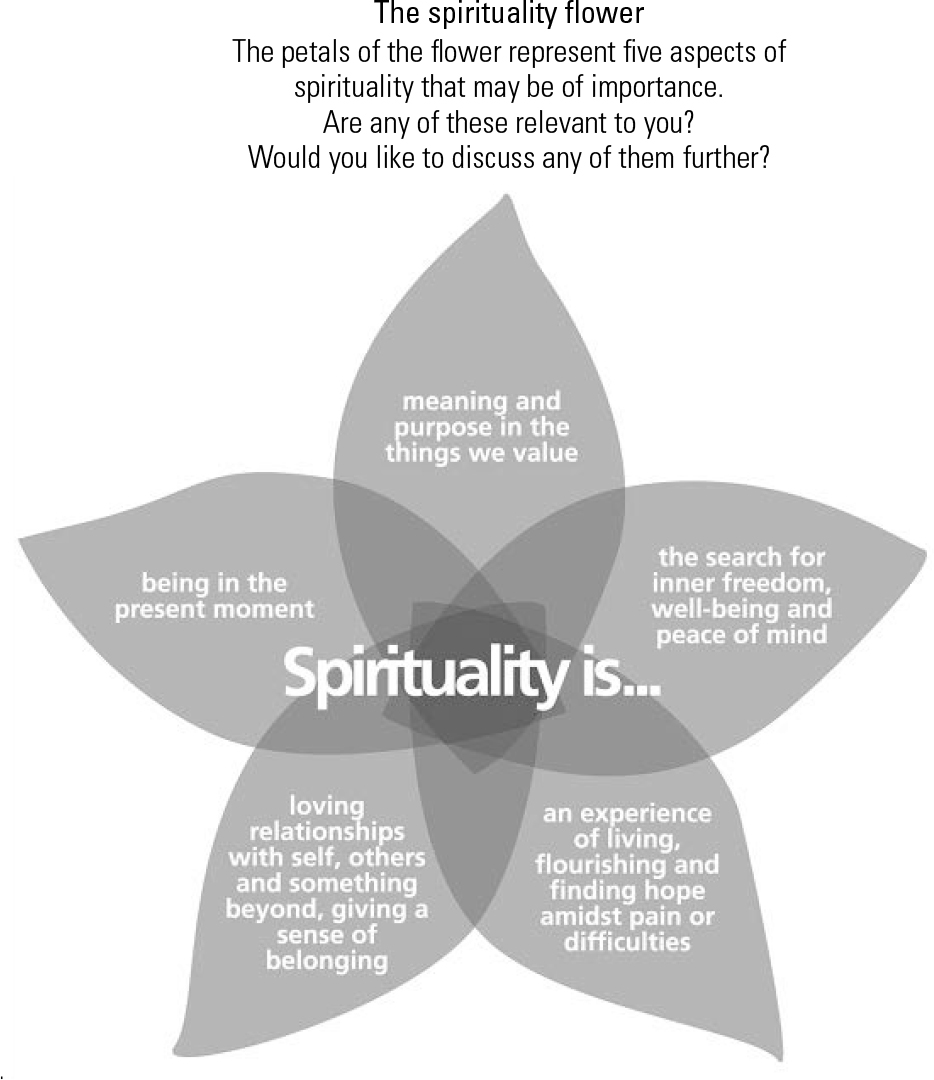

Box 2 provides a short list of the key areas of enquiry that are important in psychiatry. I do not suggest that history-taking should always address all of these domains. Rather they might be kept in mind as at least sometimes essential areas of further enquiry and as always potentially important. Enquiring about them all is, in any case, far too time consuming for routine clinical practice. At Tees, Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Foundation Trust a working group including patients and professionals has developed a ‘spirituality flower’ (Fig. 1) as a way of depicting five identified aspects of spirituality, each within a separate petal (Reference Cook, Breckon and JayCook 2012a). This flower can be shown to patients on a laminated card and a simple question asked about whether or not any of these aspects of spirituality is important or relevant to the person concerned.

BOX 2 Key areas of enquiry in a spiritual history in psychiatry

Identity – Does this person self-identify as being Christian, Muslim, Buddhist, spiritual but not religious, atheist, etc., and is this important to their self-understanding?

Relationships – What are the most important relationships in this person’s life? Family, lovers and partners are often mentioned, but also God, involvement in church/synagogue, belonging to a faith community, relationship with nature/creation, etc. Are these relationships supportive or a cause of stress?

Practices – Does this person engage in spiritual practices of any kind? This may include not only prayer, mindfulness, meditation, etc., but also such things as yoga, art, singing, dancing and writing. Do these things help when life gets hard?

Meaning and purpose – What makes life feel worthwhile for this person? What really matters? (Answers to this are often in terms of relationships – above – but may also be in terms of social action, work, hobbies and other activities seen as important, creative and fulfilling.) Are there any religious/spiritual beliefs with which the person struggles or which are causing them anxiety?

Implications for treatment – Do any of the foregoing have an impact on whether or not a patient is likely to experience problems in accessing mental health services or receiving mental healthcare?

FIG 1 The ‘spirituality flower’. Copyright © 2011 Tees, Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Foundation Trust. Reproduced with permission.

A wide range of instruments have been employed as ways of characterising and quantifying spirituality in research. As this article is primarily concerned with clinical practice, these will not be addressed here, but readers are directed to a number of helpful reviews and works of reference (Reference Hill and HoodHill 1999, Reference Hill and Pargament2003; Reference de Jager Meezenbroek, Garssen and van den Bergde Jager Meezenbroek 2012). Among these instruments, it is worth noting the Royal Free Interview for Religious and Spiritual Beliefs, in which individuals are asked to identify themselves as spiritual, religious, spiritual but not religious, or religious but not spiritual (Reference King, Speck and ThomasKing 1995, Reference King, Speck and Thomas2001). Interestingly, some of the European research undertaken using this instrument has suggested both that religion may not have the protective effect that North American research largely seems to suggest that it has, and that being spiritual but not religious might even increase the risk of psychiatric morbidity (Reference King, Marston and McManusKing 2013). A new research instrument that has arisen from patient (service-user) based research, and that understands spirituality/religion as just one aspect of recovery, is the Service-user Recovery Evaluation scale (Reference Barber, Parkes and ParsonsBarber 2012).

Treatment

Spirituality and religion have a relevance to treatment across a wide range of diagnostic categories, therapeutic modalities and subspecialties. For example, there is evidence that religious affiliation reduces the risk of completed suicide, and a knowledge of the ways in which religious beliefs and traditions influence attitudes towards suicide may be important in working with a religious patient with suicidal ideation (Reference CookCook 2014). Spiritual and religious themes not uncommonly emerge as an important aspect of making sense of, and coping with, the experiences of psychosis, and an awareness of how to respond constructively to such frames of meaning may be significant in helping patients to engage with recovery (Reference Huguelet, Mohr, Huguelet and KoenigHuguelet 2009). Particular considerations may arise where ethnic minorities are concerned (Reference Fitch, Wilson and WorrallFitch 2010), but spirituality groups can also be open and accessible to a broad cross-section of patients in at least some treatment settings (Reference Jackson and CookJackson 2005; Reference Salem, Foskett, Cook, Powell and SimsSalem 2009).

A limited number of explicitly spiritual approaches to treatment have received widespread acceptance in mental health services in Europe and North America. Among these, the spiritual but not religious approach of the Twelve Step programmes in the field of addiction recovery (Reference Cook, Cook, Powell and SimsCook 2009b), and the now widely employed practice of mindfulness (Reference MaceMace 2008), deserve special mention.

Twelve Step programmes

Endeavours to help people recover from addiction have a long history, and many programmes for recovery have been (and are) informed by a religious framework of understanding. However, it is probably the influence of Alcoholics Anonymous and its sister organisations that has had greatest impact in promoting a spiritual programme of recovery. This programme is based primarily on mutual help principles, but it also now forms the basis for many residential and non-residential professionally led recovery programmes, and Twelve Step ‘facilitation’ is offered within professionally based treatment services, especially in North America.

The spirituality of the Twelve Step programmes has been the subject of an extensive literature, and some empirical research, and has clearly been the basis on which many people with addictive disorders have built their recovery. It is concerned primarily with relationships – notably and initially the relationship with alcohol (or another object of addiction) as something over which the addict is powerless. Later steps of the programme emphasise both restoration of relationships with other people and with a ‘Higher Power’, explicitly referred to in the steps as ‘God as we understood him’ (Alcoholics Anonymous 1983). Perhaps surprisingly, this emphasis on a Higher Power of one’s own understanding has proved accessible to atheists and agnostics, as well as to members of almost all of the world’s major faith traditions.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness is usually identified as originating in the Buddhist tradition, although in fact it shows a close resemblance to contemplative practices of prayer and meditation in many of the world’s other major faith traditions, including Christianity (Reference Cook, Bingaman and NassifCook 2012b; Reference KnabbKnabb 2012). Moreover, the growing evidence base for its effectiveness as a therapeutic tool in mental healthcare usually dissociates it from its religious roots and explores its value in a much more utilitarian fashion. Unlike the Twelve Steps, it does not require belief in any kind of Higher Power or God. It is concerned much more with attentiveness to the present moment, an attentiveness that acknowledges both the distractibility of human thoughts and the presence of a range of experiences such as anxiety, craving, hallucinations or other mental phenomena.

Mindfulness has been integrated into psychotherapeutic practices of diverse kinds (Reference MaceMace 2007). In the psychoanalytic tradition, this has included a focus on both the attention given by the therapist to the analysand and the attention given by the analysand to their feelings. In the cognitive–behavioural tradition, a range of new therapies have emerged, including mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). MBCT is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence as a relapse prevention treatment for depression (NICE 2009), but it has also been employed with some evidence of benefit in addictive disorders, eating disorders, anxiety disorders, psychosis and various other mental disorders (Reference MaceMace 2008; Reference Witkiewitz, Bowen and DouglasWitkiewitz 2013).

The recovery approach

A recovery approach has become increasingly normative to mental healthcare in recent years (Care Services Improvement Partnership 2007). Key themes of the recovery approach that are also central to spirituality are shown in Box 3.

BOX 3 Key themes of the recovery approach that are also central to spirituality

-

Values

-

Emphasis on health rather than pathology

-

Hope

-

Empowerment

-

Meaning

-

Recognising expertise arising from experience

-

Recognising value of diversity – cultural, sexual, religious

-

Coming to terms with disability and ongoing illness

-

Social inclusion

-

Identity

-

Narrative

-

Detachment from/ongoing relationship with services

-

Collaborative approach to treatment

-

Personal qualities of staff

-

Constructive and creative approach

The ability of the recovery concept to articulate almost all of the key features of spirituality without use of the word ‘spirituality’, and without reference to religious frames of reference (other than in its valuing of diversity), raises again the question of whether or not explicit reference to spirituality and/or religion is necessary to address the key themes and benefits of spirituality in practice. Some authors have referred to ‘implicit spirituality’ as a way of acknowledging that some key issues referred to by others as being ‘spiritual’ can in fact be discussed without using the language of spirituality at all (Reference Pargament, Krumrei, Aten and LeachPargament 2009). There would seem to be little doubt that spirituality can be conveniently located within the recovery agenda, and that many of its significant concerns are most readily addressed from this perspective for the purposes of clinical governance and service planning and delivery. However, a key concern of both spirituality and religion that is not obviously addressed within this agenda is that of transcendence.

Transcendence

Transcendence has been located as a key component of both spirituality and religion, but in fact it is capable of a range of interpretations, some of which clearly do not require the language of traditional religion (Reference Cook and CookCook 2013c). Mindfulness focuses on the immanent (present reality, including the objects of sense perception as well as the subjective experiences of consciousness), thus demonstrating that spirituality is not only concerned with transcendence. Many other spiritual and religious concerns, in contrast, do seem to be focused on issues of transcendence. On the one hand, this may just be a reaching beyond (or deep within) oneself to ‘transcend’ what has previously been perceived as humanly possible. On the other hand, it is often a spiritual, divine or supernatural reality that is sought (as in the Higher Power of the Twelve Step programmes) as a source of comfort, support and hope or healing.

Conclusions

Spirituality and religion are important to people, and they evoke strong feelings. My own clinical experience and conversation with colleagues show that, for some patients, this has meant that they have felt patronised, misunderstood and alienated when their attempts to talk about things that matter to them have been labelled by psychiatrists as pathology. For others, it has been intrusive and offensive when they have felt that professional power has been used to impose an agenda that reflects more the personal values of the psychiatrist than it does those of the patient. Much depends, therefore, on the sensitivity and skill of the clinician in ascertaining what matters to the patient and how it may most helpfully be acknowledged and addressed in treatment. Proselytising, whether for religious, political or atheistic beliefs, is completely unacceptable and is an abuse of professional power.

Much of what has been discussed in this article does not require the language of spirituality or religion, and it is to be hoped that the recovery agenda will indirectly promote many of the concerns of spirituality without evoking its controversies. It is central to the good practice of psychiatry that clinicians are able to elicit the values and concerns of their patients, emphasise health over pathology, evoke hope, acknowledge diversity, and assist in finding meaning in the midst of bewildering and overwhelming experiences. However, for some patients, the language of spirituality and/or religion is likely to provide a more helpful (and hopeful) medium for the conversation. The good psychiatrist will gain at least a degree of fluency in this language, sufficient to recognise when and how to affirm helpful frameworks of meaning and adaptive coping resources (Box 4).

BOX 4 Clinical vignette

A 32-year-old woman presented with a recent history of low mood and auditory verbal hallucinations. She asked if she could see a Christian psychiatrist. The psychiatrist whom she initially saw was an atheist, but he assured her that he would be respectful of her beliefs and suggested that she might like to talk to a member of the chaplaincy team. This was duly arranged. It transpired that the woman had been engaged in a relationship with a married man, about which she felt deeply guilty. She identified the voices that she heard as evil spirits sent to torment her. Working closely together, the psychiatrist and chaplain were able to encourage her to accept pharmacotherapy and reassure her that exorcism was neither necessary nor likely to be helpful. The chaplain was able to reassure her that a Christian psychiatrist would not have offered any different treatment and, after discussion with the psychiatrist, agreed to offer the ministry of reconciliation (confession and absolution). She made a good recovery.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 As regards spirituality:

-

a spirituality is more or less the same thing as religion

-

b people identify themselves as either spiritual or religious, but very rarely as both

-

c religion is concerned only with rules, institutions and hierarchies and does not allow for the subjective or experiential aspects of spirituality

-

d in research, religion is less easy to measure than spirituality

-

e spirituality is often concerned with relationship with oneself, others and a wider or higher reality.

-

-

2 The research evidence base concerning the benefits of spirituality/religion for mental health is contentious because:

-

a many early studies were of poor methodology and not designed to study the influence of spirituality/religion

-

b religiosity is difficult to measure in research

-

c there have been very few published studies

-

d adopted definitions of spirituality/religion and mental health make no difference to whether positive or negative associations are found

-

e findings have no relevance to clinical practice.

-

-

3 Assessment of spirituality in clinical practice:

-

a is usually unnecessary

-

b can be undertaken with help of the ‘HOPE’ acronym

-

c is necessarily time-consuming

-

d is unimportant if the patient is an atheist

-

e should not influence treatment planning.

-

-

4 Boundaries not relevant to good handling of spiritual/religious matters in psychiatric practice include:

-

a professional knowledge and expertise

-

b those between chaplaincy and the clinical team

-

c secular v. religious

-

d personal v. professional

-

e ego boundaries.

-

-

5 The recovery approach in mental healthcare:

-

a overlaps extensively with the concerns of spirituality

-

b explicitly addresses spiritual, but not religious, concerns

-

c avoids the need to explicitly address spiritual or religious concerns

-

d is difficult to combine with spiritual/religious care

-

e addresses all of the key concerns of spirituality/ religion.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | e | 2 | a | 3 | b | 4 | e | 5 | a |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.