Although the study of radical left parties (RLPs) has a prominent history in comparative politics (e.g. Blackmer and Tarrow Reference Blackmer and Tarrow1975; Tarrow Reference Tarrow1967), only recently have party politics scholars again started to show a growing interest in the topic (e.g. Charalambous and Lamprianou Reference Charalambous and Lamprianou2016; Gomez et al. Reference Gomez, Morales and Ramiro2016; March and Keith Reference March and Keith2016; March and Mudde 2005). The increase in relevant publications is in line with a remark by Luke March (Reference March2011: 4), who underlines the fact that considering their average electoral strength and the number of times they have been in government, RLPs should receive as much scholarly attention as Green and radical right parties have.

In the respective literature, two main subjects of interest are, first, the conditions for electoral success of RLPs and, second, their participation in government (e.g. March Reference March2011; Olsen et al. Reference Olsen, Koß and Hough2010a). In addition, a growing amount of research has emphasized the importance of local and regional politics for RLPs, highlighting factors that shape their development at the subnational level (e.g. Hough and Verge Reference Hough and Verge2009; Olsen and Hough Reference Olsen and Hough2007; Ştefuriuc and Verge Reference Ştefuriuc and Verge2008). In this article, I contribute to these debates by analysing the ‘curious success’ (Kuhn Reference Kuhn2013) of the Communist Party (KPÖ) in Graz, which is the second biggest city in Austria with around 285,000 inhabitants. While the Communists stood at less than 2 per cent of the vote in 1983, they rose, despite the fall of the Soviet Union, to 7.9 per cent within 15 years, entering local government in 1998.1 Once in government, the party did not lose vote share, but even reached around 20 per cent three times in the four elections since then. The success in Graz also helped the party to enter the regional legislature of Styria in 2005. The electoral rise of the KPÖ Graz represents a ‘least likely case’ (e.g. Bennett and Elman Reference Bennett and Elman2006: 462), as it is in contrast to many theoretical expectations in the literature on RLPs. My research question is thus: Why has the KPÖ Graz been so electorally successful since the 1990s?

How does the case of the KPÖ Graz contradict previous findings? First, while single instances of electorally highly successful RLPs are not completely alien to recent Western European history (e.g. the communist AKEL in Cyprus; Dunphy and Bale Reference Dunphy and Bale2007), the political context of Austria makes the rise of the KPÖ Graz unlikely. The country is well known for the electoral irrelevance of RLPs, which have not been represented in national parliament for more than half a century. In Austria ‘the communist tradition was all but extinguished prior to 1989’ (March Reference March2011: 196). In no other region, apart from Styria, has there been anything that even closely resembles the rise of the KPÖ Graz in recent decades. On the contrary, Austria’s political system has been shaped by an exceptionally strong radical right (e.g. McGann and Kitschelt Reference McGann and Kitschelt2005). And even though there is some tradition of communist organization in Styria, there is no strong communist legacy that can explain the strength of the party as it does in other cases (March and Rommerskirchen Reference March and Rommerskirchen2015).

Second, this analysis shows a case of long-term electoral success of a party despite, or rather, because of its participation in government. In the literature, scholars overwhelmingly report on negative experiences for RLPs, both when in government and when supporting a minority government. Some recent episodes are described as ‘unhappy in the extreme’ (Newell Reference Newell2010: 62), referring to the experience of the Italian Rifondazione Comunista as coalition party, and as ‘the paradigmatic example of what not to do’ (Bale and Dunphy Reference Bale and Dunphy2011: 279), referring to the case of the Swedish Left Party supporting a minority government. Only slightly less negative is the portrayal of the Finnish Left Alliance’s government participation – ‘[t]he experience has been difficult and the results mixed’ (Dunphy Reference Dunphy2007: 52). A more general verdict on Western European RLPs in government states that their performances have been ‘far from encouraging to date. Their few achievements have to be set against many potential pitfalls’ (Dunphy and Bale Reference Dunphy and Bale2011: 488). Large-N studies also show that, in general, European RLPs have experienced a reduction in vote share when serving in government (Buelens and Hino Reference Buelens and Hino2008: 159–60; Olsen et al. Reference Olsen, Koß and Hough2010c). This has, however, not been the case for the KPÖ Graz – atypically, its electoral results skyrocketed after its government participation. Indeed, since 2012 the party has even been the second largest in the local council.

Third, the impact of European RLPs in government has been described as ‘relatively negligible’, as they tend to a ‘lack of policy achievement’ (March Reference March2011: 207, 210). They are qualified ‘as policy-takers (and, if they are lucky, veto-players) rather than policy-makers in government’ (Bale and Dunphy Reference Bale and Dunphy2011: 278). Such a negative perspective is not valid for the KPÖ Graz, though: its government participation has had a substantial impact on housing, the policy area it has been in charge of. Here, the Communists have been able to pursue policies of decommodification, quite unlike the governments of other municipalities in Austria and beyond. The party’s impact on housing again contributed to its successful electoral record.

Fourth, competition from green parties and the radical right has been found to decrease the likelihood of electoral success for RLPs significantly (March and Rommerskirchen Reference March and Rommerskirchen2015). However, the national strength of both the radical right, the Freedom Party (FPÖ), and the Greens is reflected in the composition of the local council in Graz. Both parties have also participated in majority coalitions or less formal majority pacts in the last two decades, highlighting their established role in local politics. Despite these rivals, the KPÖ Graz has been competitive.

Fifth, scholars have asserted that, unlike in Eastern Europe, in Western Europe communist parties are the most endangered species of RLPs, with a name reminding voters of times past and with a leadership that rarely adapts to current political circumstances (March Reference March2011). Indeed, in Western Europe the most electorally successful RLPs since the 1990s have not been communist parties. In this case, too, the KPÖ Graz serves as counterexample.

My research emphasizes both the agency of political players and the importance of institutional factors at the subnational level for the electoral success of RLPs. In referring to agency, I show how the long-term strategies of RLPs can boost their electoral results. Therefore, this study also meets calls to fill gaps in research on the internal life of RLPs as it adds to recent conclusions coming from large-N research that can, by its nature, focus only on external factors (March and Rommerskirchen Reference March and Rommerskirchen2015). My research sheds light on the crucial strategic decisions of the KPÖ Graz leadership, especially the choice to focus on housing policies, in order to understand the party’s atypical electoral success. Here, the Graz party differed significantly from other branches that did not start pursuing more promising strategies.

Referring to institutional factors at the subnational level, I show how a system of proportional government permits a political party to participate in government without the need to form a coalition. As required by Austrian constitutional law, the city charter of Graz allows for the proportional allocation of government members. After achieving a given proportion of the vote, a party has the right to be included in government, even without a coalition agreement with other parties. The KPÖ Graz has been able to exploit this feature of a consensus-oriented local polity. Although we still lack systematic findings on the electoral success of RLPs at the subnational level, the finding that the Spanish Izquierda Unida rarely suffered electorally when in regional government (Ştefuriuc and Verge Reference Ştefuriuc and Verge2008: 169) might indicate that RLPs generally fare better in subnational than in national government. However, ‘a decidedly inferior power relationship’ within left coalitions in the German Länder, with the advantage for the Social Democrats (Olsen and Hough 2007: 19), might imply a general lack of policy achievement for RLPs also on that level. While this article cannot provide systematic findings on these issues, it goes beyond the scope of the literature on governing RLPs, which usually focuses on coalition participation, both at the subnational and national level (e.g. Hough and Verge Reference Hough and Verge2009; Olsen et al. Reference Olsen, Koß and Hough2010a). Instead of analysing RLPs in government coalitions, I show how the possibility of governing without forming a coalition contributes to the rise of a RLP.

Thus, studying the rise of the KPÖ Graz has many merits for the study of European RLPs in general. However, the case itself is also greatly overlooked: the party’s growth has been ignored by political scientists in Austria. Important recent pieces on the KPÖ Graz are a journalistic account by an anarchist writer (Kuhn Reference Kuhn2013) and a biography of Willi Gaisch, the former leader of the Styrian party branch (Wisiak Reference Wisiak2012). The objective of this study is thus not only to make a theoretical input to the field of party politics, but also to contribute to the study of perhaps the most counterintuitive empirical phenomenon in contemporary Austrian politics.

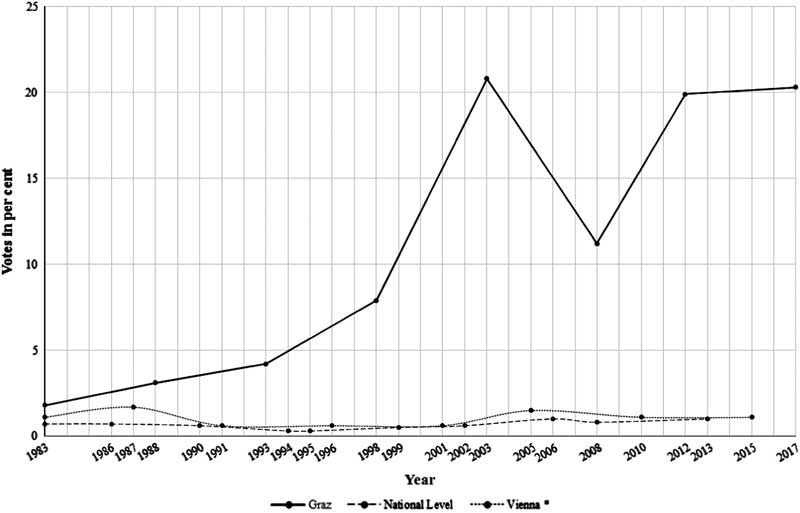

In the elections in 2012, the KPÖ Graz finished for the first time as runner-up, beating even the Social Democrats (SPÖ), traditionally the dominant heirs to the Austrian labour movement, and ending up behind only the Conservatives (ÖVP). This second place was not a fluke: in 2017, the KPÖ managed to stay second, ahead of the FPÖ, despite the radical right party’s constant lead in the national polls and its candidate’s strong showing at the presidential elections the year before. These developments correspond to the notable electoral growth of the local KPÖ since the beginning of the 1990s. While in 1983 the KPÖ did not win even 2 per cent of the vote, since 1998 the party has not only been part of the city government, but has managed to attract around 20 per cent of the vote in 2003, 2012 and 2017. In no other part of Austria has the party had such an impact in recent history. At the national level and in almost all other large cities, legislative representation is only a distant memory for the KPÖ. In some parts of Austria, the party is so weak that it no longer participates in regional elections. Figure 1 shows the diverse electoral trajectories of the KPÖ in Graz, in the capital, Vienna, and on the national level – the striking difference merits explanation.

Figure 1 Electoral Results of the KPÖ on Different Levels. * The Viennese branch joined forces with others to run as Bewegung Rotes Wien (Movement Red Vienna) in 1996 and as Wien Anders (A Different Vienna) in 2015.

My full argument is that the performance of the KPÖ Graz can be explained with a combination of agency and institutional factors. Key institutional features of the local polity in Austria – that is, the ‘political opportunity structure’ or ‘external supply side’ (e.g. Arzheimer and Carter Reference Arzheimer and Carter2006; March and Rommerskirchen Reference March and Rommerskirchen2015; Mudde Reference Mudde2007) – provided the necessary setting. The lack of an electoral threshold helped the KPÖ to survive in the city council up to the 1980s. In 1998, the system of proportional government permitted the party to enter government without the need to form a government coalition and with not even 8 per cent of the vote. Additionally, when in government, the possibility of direct democracy, which ultimately permits the initiation of non-binding referendums ‘from below’, increased the leverage of the Communists in conflicts with other parties. What is more, the highly effective strategic decisions taken by leading KPÖ politicians – that is, the ‘internal supply side’ or agency (e.g. Art Reference Art2011; Jasper Reference Jasper1997; Müller and Strøm Reference Müller and Strøm1999) – caused the rise of the party. This was only possible because of the Communists’ long-term focus on housing policy. The party managed to ‘own’ (e.g. Petrocik Reference Petrocik1996) the issue, connecting it to their more fundamental critic of capitalism – a process of ‘frame extension’ (Snow et al. Reference Snow, Rochford, Worden and Benford1986). In 1998, the ‘hard choice’ (Müller and Strøm Reference Müller and Strøm1999) to enter government, despite the danger of not being able to deliver, paid off. The other parties made the mistake of giving the Communists control over the housing department. While in charge of it, the party has been, to some extent, able to pursue the decommodification of housing, a policy-seeking approach that also resulted in electoral success.

Methodologically, I rely on 15 interviews with 13 current and former politicians and activists of the KPÖ Graz, including its past and its current leader, further deputies in the local council of Graz and the regional legislature of Styria, party staff, and rank-and-file members. The interviews were conducted in January 2015 and in January 2016. If not otherwise specified, the empirical data in this work is derived from these interviews. This approach corresponds to other research in party politics, ‘deliberately opting . . . to summarize and paraphrase what we were told in order to say as much as we can in the limited space available’ (Bale and Dunphy Reference Bale and Dunphy2011: 277; a similar approach is provided by Luther Reference Luther2011, for example). The interviews lasted between one and two and a half hours and included questions on the history of the party, personal views on key developments and events, as well as on personal biographies, especially related to party activism. Although interviews with politicians from other parties would certainly have provided useful additional empirical data, this was beyond the practical scope of this research. Apart from interviews, I study key qualitative data on the issue, such as official party documents and other publications of the party’s politicians on issues such as party history and strategy. My ‘dependent variable’ is electoral success – therefore, ultimately, I focus on the vote dimension of the well-known policy, office and vote triad (Müller and Strøm Reference Müller and Strøm1999). Still, this should not imply that the party leadership regards itself primarily as vote-seeking. I examine my case in a theory-guided analysis, highlighting the ‘independent variables’ in order of their chronological importance.

In the next section, I make my argument in detail, presenting and analysing the recent history of the KPÖ Graz. In the conclusion, I not only summarize the main findings, but also highlight necessary research questions for the future study of RLPs.

The Rise of the KPÖ Graz

The Precondition: The Party’s Survival in the Local Council

Historically, the Austrian Communists have never been a strong political force. In the interwar period, during the First Republic, the party existed in the shadow of the rhetorically left ‘Austro-Marxist’ Social Democrats (for a history of Communism in Austria until 1938, see McLoughlin et al. Reference McLoughlin, Leidinger and Moritz2009). During the National Socialist dictatorship, the KPÖ played a significant role in the small resistance movement. After the Second World War, with the occupation of Austria by the Allies, the KPÖ experienced its most influential period. With the Soviet Union’s presence in Austria, the party was part of the first two national governments of the Second Republic, in coalition with the Social Democrats and the Conservatives. However, the party’s electoral share was only 5.4 per cent in 1945. In 1947, the KPÖ left the government. Four years after the end of the occupation of Austria, in 1959, the party failed to reach the required 4 per cent threshold and dropped out of national parliament altogether. This legislative demise was not restricted to the national party; most of the regional and local branches also lost council representation sooner or later. In 1970, the KPÖ Carinthia and the KPÖ Styria were the last two regional branches that were voted out. Already one year earlier, the Viennese KPÖ had shared the same fate (for more details on the party’s history from the perspective of a former head of the national KPÖ, not on close terms with the Styrian branch, see Baier Reference Baier2009).

Until the 1980s, the KPÖ Graz was merely a weak force in the Gemeinderat, the city legislature of Graz. However, in stark contrast to the fate of the KPÖ in other parts of Austria, the Graz branch had at least always remained in local council since 1945. How did it manage to survive there in the decades following the demise of the national party? The answer is straightforward: contrary to the national and eight of the nine regional legislatures in Austria, there is no electoral threshold for entering local councils such as the one in Graz. Therefore, only a minimal share of the vote is necessary to gain one seat in the Gemeinderat, and this the party always managed to achieve. All the same, also in Graz the party could achieve only very weak electoral results. In fact, in the elections of 1983 the KPÖ Graz attracted so little support that it almost lost representation, despite the minimal requirements. In the end, 174 votes were decisive – attracting the support of only 1.8 per cent of the electorate was a new record low. Still, the result narrowly secured the mandate for Ernest Kaltenegger, who had become a member of the Gemeinderat two years earlier, on the death of his predecessor. Initially involved in the youth group of the SPÖ, Kaltenegger became active for the Communists in 1972. When he became city councillor, Kaltenegger was 31 years of age. He was to be the party’s key public figure for the next 25 years. In 1988, the KPÖ again secured a seat, this time gaining 3.1 per cent of the votes.

The continued presence in the city council was a necessary condition for the party’s rise. It is implausible that the KPÖ Graz could have achieved its later success had there been a high electoral threshold, even if its leading figures had made the wise strategic decisions they later did. In the presence of a substantial electoral threshold, the party would have become an extraparliamentary force sooner or later. Even for many of their sympathizers, a vote for the KPÖ would have turned into a ‘lost vote’, and the establishment of the party in the local council would have been unlikely.

Therefore, until the 1980s, the KPÖ Graz benefited from one aspect of the local ‘political opportunity structure’, often also called the ‘external supply-side’ (e.g. Arzheimer and Carter Reference Arzheimer and Carter2006; Mudde Reference Mudde2007). One popular definition of political opportunity structure includes a reference to ‘[t]he relative openness or closure of the institutional political system’ (McAdam Reference McAdam1996: 27), influencing how political players develop. The legislative survival of the KPÖ Graz is a case in point. The local level of the Austrian polity is particularly open – the lack of thresholds allows even very small groups of the electorate to be granted representation. Remaining in the city council provided the necessary foundation for the party’s future rise. With a threshold similar to Austria’s regional legislatures or the national parliament, the KPÖ Graz would have disappeared from the legislative arena at some point, with only a small chance of re-entering. This argument is in line with findings from large-N studies that identify a low electoral threshold as one of the factors explaining electorally successful RLPs in Europe (March and Rommerskirchen Reference March and Rommerskirchen2015).

Party Strategy: The Focus on Housing

A favourable external setting does not automatically lead to electoral success. The lack of an electoral threshold in Graz only made the survival of the local KPÖ possible. For example, even though in Austria’s third biggest city, Linz, the KPÖ also benefited from the lack of an electoral threshold, the local branch only managed to gain one seat in some of the elections in the last three decades. Therefore, in order to understand the rise of the KPÖ Graz we need to turn to the actions of its politicians.

The constantly poor electoral record led the KPÖ Graz to reconsider its strategy. Leading figures within the party saw the need to focus on more specific issues that would matter directly to a significant share of the population, rather than making abstract demands for large-scale social change, which – especially after the fall of the Soviet Union – would have found only modest appeal. In doing so, the party made a strong shift by placing emphasis on local issues, especially housing. This process had already started in the 1980s. The personal experiences of Kaltenegger himself, who stated that he had changed accommodation 12 times up to the mid-1980s, contributed to this reorientation. In his opinion, housing could be used as an example of how capitalist economies fail to deliver society’s basic needs. Instead of promising a bright socialist future at an unspecified point in time, the party leadership thought that housing policy lent itself to tackling the immediate problems of many. Later, the focus on the issue intensified. In 1991, members were inspired by an exchange with the Lille branch of the Parti Communiste Français, particularly in regard to their ‘téléphone d’urgence’, a hotline to call local deputies for help in case of an eviction (Parteder Reference Parteder2013).

The focus on housing did not imply a move towards the political centre but, rather, a shift of emphasis: The manifesto of the Styrian KPÖ analyses capitalism and calls for socialism without discussing housing (KPÖ Steiermark 2012). Still, on the local level, in the words of one of the most influential politicians of the Styrian KPÖ, the work on the housing question should highlight the organization’s ‘use value as a helpful party for the people’ without the need for ‘political-ideological transfiguration’ (Parteder Reference Parteder2013).

For the party leadership, the poor quality of public housing and attempts by private landlords to evict long-term tenants with comparatively cheap rental contracts were particularly important. The KPÖ Graz decided not to simply copy the example of Lille, but to adapt it to its own local situation; its politicians avoided intervening more directly in the way the French Communists did, for example by blocking evictions. Similar to the French model, though, the party created an emergency hotline, which it advertised in the local media. Through the hotline, the party provided legal advice and later even financial support for tenants. Controversial actions by landlords were reported to journalists – the Communist politicians actively sought media attention. Consequently, the KPÖ Graz started to ‘own’ (Petrocik Reference Petrocik1996) an issue of local politics.

What were the electoral consequences of this move? The results of the Graz elections of 1993, the first to be held after the fall of the Soviet Union, came as a surprise. With 4.2 per cent of the votes, the KPÖ gained a second member in the Gemeinderat and Elke Kahr, who later succeeded Kaltenegger, became the additional deputy. Note that in Vienna a similar result would still have left the party outside the city’s council. The big step forward occurred in 1998, when the KPÖ Graz managed to gain 7.9 per cent of the votes, overtaking the Greens and becoming the fourth largest party. Therefore, within four years, the KPÖ Graz was able to double its seats.

The growth of the party in the 1990s cannot be explained by features of the political system, but by the decisions taken by the party’s leadership. This corresponds to a focus on the ‘internal supply-side’ (e.g. Art Reference Art2011; Luther Reference Luther2011) and ‘culture, biography, and creativity’ (Jasper Reference Jasper1997, Reference Jasper2004) in politics, emphasizing the agency of political players. At least on the local level, centralized and orthodox parties, such as the Austrian Communists in the 1980s, were not immune to innovation. Generational change within the party contributed to the possibility of this transformation, even though not everyone was on board immediately. The decision to reconsider the party’s strategy also demanded the leadership’s willingness to deal firmly with a new subject, considering that technical expertise was required for the effective support of affected tenants. Kaltenegger’s personal experience with the housing situation in Graz is an example of how biography can contribute to political decisions. Ultimately, the shift was a process that took years, and intra-party support for it grew with its success.

In the language of the widely used framing approach, the connection of the Communists’ critique of capitalism with housing policy resembles ‘frame extension’, the effort ‘to enlarge [one’s] adherent pool by portraying its objectives or activities as attending to or being congruent with the values or interests of potential adherents’ (Snow et al. Reference Snow, Rochford, Worden and Benford1986: 472). From this perspective, the emphasis on housing cannot be regarded as a moderation in the party line, but rather as a new focus based on the same principles. According to a main party figure, accentuating housing issues can be an effective strategy for RLPs because many people agree that ‘an apartment should not be treated like any other good’ (Parteder Reference Parteder2013).

In short, the reason for the party’s rise in the 1990s was its intensive emphasis on housing policy: the party ‘aligned’ (Snow et al. Reference Snow, Rochford, Worden and Benford1986) its anti-capitalist critique by starting to ‘own’ an issue of local politics (Petrocik Reference Petrocik1996). This step was in clear contrast to other traditional Communist parties failing to reach out to wider masses at the end of the twentieth century.

Communists in Government – But Not in a Coalition

The 7.9 per cent gained in the elections of 1998 were important not only because of the increase in deputies; this outcome was decisive for the future rise of the party. As a result of the party’s electoral strength, the proportional government system allowed the KPÖ to appoint one of its members to the local government. Therefore, an element of a favourable political opportunity structure or external supply-side allowed the party to take this step. The inclusion of the legislative minority in government is another dimension of the ‘openness’ of the polity of Graz, and of Austrian local politics in general.

Potentially, controlling a governmental department while still being able to criticize the legislative majority can be a very comfortable strategic position. However, the decision whether or not to enter government was difficult for the party. Although government inclusion did not require a coalition agreement or any other formal compromise, Kaltenegger maintained that ‘we actually did not want to’ enter. The party’s leading figure regarded the Communists as an oppositional force and feared that government inclusion would have problematic consequences. He was concerned that external constraints would prevent the party from delivering desired policies: First, an adversarial council majority decided on policies and budget. Second, he thought that the dominance of austerity limited local politicians’ room for manoeuvre. Therefore, the Communists unsuccessfully demanded a reduction in the size of the local government from nine to seven members, which would have kept them from entering. Ultimately, Kaltenegger argued that the KPÖ decided to enter local government to prevent another party from taking the seat, which would have been a step not appreciated by its voters.

Therefore, the party leader was confronted with a ‘hard choice’ (Müller and Strøm Reference Müller and Strøm1999) or a ‘strategic dilemma’ (Jasper Reference Jasper2004, Reference Jasper2006), facing two options with different benefits and drawbacks. Government inclusion promised the possibility of implementing policy, the resources and media attention of an office, and, perhaps, more votes in future elections. However, these positive prospects were far from certain: a member of the city senate has only limited ability to act – most importantly, he or she still remains largely dependent on majority decisions. Therefore, the Communist leadership feared the possibility of being in government without the ability to govern as they pleased. Social movement scholars describe this later scenario as ‘co-optation’ – gaining access without the achievement of substantial goals (Gamson Reference Gamson1975).

The role of other parties should also be underlined here. In line with the Communists’ political emphasis, Kaltenegger was given control over the housing department. This decision of the governing majority – a coalition of Social Democrats and Conservatives – turned out to be a major strategic blunder. In the view of leading Communist figures, the majority coalition intended to set a trap by giving the Communists control over this portfolio. For the Social Democrats in particular, then the mayor’s party, the move turned out to have severe long-term electoral consequences.

The Continuous Rise of the KPÖ Graz in Government

In hindsight, the Communists’ decision to enter government proved wise. In the elections of 2003, they gained a massive 20.8 per cent of the vote share and became the third strongest party. The KPÖ was merely 5 per cent behind the SPÖ and stronger than the heavily losing radical right FPÖ, which was self-destructing in national government at that time (Luther 2011). This result allowed the Communists to nominate a second government member. The party leadership decided to appoint an experienced former Green local councillor.

How was the KPÖ Graz able to increase its electoral appeal despite the constraints of government? Again, a combination of strategic decisions and a favourable external setting explain the performance.

Although the KPÖ Graz was not part of the council’s majority coalition, the party was able to advance some key goals regarding housing. In opposition, the KPÖ was already able to press for its agenda by making use of direct democracy. In the mid-1990s, a major campaign of the KPÖ pushed for limiting the share of income needed to be spent on public housing rents. Even at this point, the party was already able to mobilize considerable political support: it collected about 17,000 signatures. However, the leadership did not dare to push for a referendum on the issue and used the option only to demand a debate in the council – the KPÖ politicians were not fully convinced about their prospects of winning a non-binding Volksbefragung. Ultimately, their initiative led to a law providing for the possibility of compensation if public housing costs exceed one-third of a household’s income, with some further possible alleviations. According to Kaltenegger, this campaign was one of the factors that explain the electoral success of 1998. Therefore, while the party was in opposition, the availability of direct democratic instruments had already provided the KPÖ with the opportunity to have some political impact and proved to themselves and their rivals that they could mobilize considerable public support.

When in government, the KPÖ Graz demanded the refurbishment of substandard public housing apartments, as a considerable number of them lacked appropriate showers. The KPÖ aimed to invest in bathrooms, while the majority coalition did not want to grant it the financial resources to do so. At the same time, Graz was selected to become the European Capital of Culture in 2003. Referring to that, the party campaigned with the slogan ‘Auch das ist Kultur. Ein Bad für jede Gemeindewohnung’ (‘This is culture as well: a bathroom for every public housing apartment’). In talks with the governing majority, the KPÖ threatened to collect signatures for a Volksbefragung, connecting the costs for new infrastructure to host the European Capital of Culture to possible alternative investments in public housing. The strategy worked – eventually, the majority parties granted the required budget. However, without the threat of a referendum, it is unlikely that the other parties would have conceded to the Communists’ demands. In 2004, the party did initiate a referendum, this time against the privatization of public housing. Although the result clearly rejected any possible privatization, the turnout was below 10 per cent. Still, the party leadership believes that the referendum had an important influence on the council majority.

Therefore, despite its minority position in the local council and the lack of a coalition agreement with other parties, the party’s concerns about not delivering in government were dispelled. Again due to an institutional feature of the open local polity, a non-binding referendum ‘from below’, the party could gain some political leverage. Here, the polity of Graz is again far more open than the national level of Austria, where binding and non-binding referendums are only a top-down instrument.

The KPÖ Graz has also pursued other strategies in order to connect to a wider public. The party has tried to reach out, especially with Stadtblatt, the party’s magazine, regularly and continuously sent to every household since the mid-1990s and, in the view of several party figures, an important component of the party’s success. Furthermore, KPÖ activists engaged in street activism, most prominently as part of Plattform 25 in 2010 and 2011, mobilizing against welfare cuts by the Styrian regional government. The importance of the different attempts to reach out to the wider public corresponds to the view of Kaltenegger: ‘One should never rely only on parliamentarism, otherwise you are dead.’

Clearly, it was not only the fact that the party found ways to pursue some of its policies that contributed to sustaining its electoral strength, but also that these policies appealed to substantial parts of the electorate. With regard to housing, the party pursued policies of decommodification. According to Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990: 21–2), ‘[d]e-commodification occurs when a service is rendered as a matter of right, and when a person can maintain a livelihood without reliance on the market’. For left-wing scholars who debate what the radical left should do in government, decommodification is exactly what it should advance (e.g. Wallerstein Reference Wallerstein2002; Polanyi Reference Polanyi2001 [1944] famously criticized the commodification of labour, land and money during the ‘Great Transformation’). The purpose of public housing is exactly this: to offer alternatives to the private housing market without the aim of profit maximization by the municipality. The Communists were in charge of a policy area that had decommodification as its inherent idea. Among the housing-related actions of the party since the 1990s, mentioned above, were the creation of a telephone hotline as well as activism for a cap on rents for public apartments, and for their refurbishment. The long-term head of the Styrian party branch also regards the construction of new public apartments and the establishment of an apartment deposit fund as important policy successes (Parteder 2013). A new aim of the party is to make landlords pay broker commissions instead of tenants (Parteder Reference Parteder2015). The appeal of the KPÖ’s policies within the electorate was also strengthened by the neglect of public housing in many other Austrian municipalities. In Vienna, for example, the Social Democratic government stopped the construction of new public apartments in 2004. The importance of the Communists’ focus on housing is underlined by the observation that ‘[t]he most successful [radical left] parties . . . present themselves as defending values and policies that social democrats have allegedly abandoned’ (March Reference March2011: 23), although this is not the main self-representation of the KPÖ Graz.

At the same time, the party was in the enviable position of being able not to vote for any policies it did not support – the party was not bound to any coalition agreement as it only was in government due to a constitutional provision. The local polity allowed the Communists to avoid one of the hard choices that parties in government often have to face; the question of what policy objectives to sacrifice in order to gain office did not have to be answered by the party. Due to their radical stance against the status quo, this dilemma has often been particularly tricky for RLPs (Olsen et al. Reference Olsen, Koß and Hough2010b), frequently causing severe intra-party division – not so in the case of Graz. The subnational polity not only eliminates many controversial topics for RLPs (for example, foreign policy), but it can also provide institutional settings of benefit to them. This finding gives some answers to the question of whether different types of subnational polities lead to different political outcomes (Vatter and Stadelmann-Steffen Reference Vatter and Stadelmann-Steffen2013: 88).

Apart from the pursuit of policy, another key aspect of the party’s continued appeal in government was its direct financial help for people in need. The KPÖ Graz requires that its holders of official positions transfer a substantial share of their personal income to the party account. This money is then distributed to people in need. Each year, the party organizes a press conference, the ‘Open Accounts Day’, informing the public about the respective spending. It is another strategy that does not rely on the decision of any external majority, but which still benefits from government participation due to the additional income generated from the party’s growing number of public office holders and the associated increase in media attention – the ‘Open Account Day’ is one of the few Communist policies that the national media also picks up.

The Consolidation of the KPÖ Graz as a Governing Party

In 2008, the KPÖ Graz faced its first electoral loss since 1983, losing almost half of its support. The party could only convince 11.2 per cent of the electorate. Three years before, Kaltenegger had left local politics and successfully ran for a seat in the Styrian Landtag – for the first time in 35 years the KPÖ was again represented in a regional legislature. However, Kaltenegger’s move to the Landtag placed the position of the party in Graz at risk. There, Elke Kahr succeeded him. Although the success of the KPÖ cannot be reduced to the personality of Kaltenegger, Kahr was unable to repeat the 2003 result in 2008 (which corresponds to findings on the impact of leadership changes on RLPs; March Reference March2011: 197). The reaction to the disappointing results within the party was mixed: some were shocked, while others regarded the results as still being exceptional by the party’s standards. Not everyone blamed the change at the top for the losses, however. Also, the campaign was criticized by some party members for not being substantial enough. Still, 2008 was not the beginning of a long-term descent. After the continuation of its by now tested strategies and the increase of Kahr’s level of familiarity among the electorate, the KPÖ Graz again reached 19.9 per cent in 2012, almost the same share of votes as it had in 2003, proving the durability of its strength. Moreover, this time the KPÖ overtook the SPÖ and became the second strongest party in the Gemeinderat, behind only the Conservatives. In 2017, the KPÖ defended its second place, this time gaining 20.3 per cent. Then, not even the FPÖ could get ahead of the Communists, although the radical right party has topped the national polls for many years and almost clinched the country’s presidency in 2016.

Still, the Communists have remained outsiders in the local party system. Already in 2003, they had rejected the idea of entering a coalition with the Social Democrats and the Greens. In 2012, although the second biggest party is regularly granted the right to appoint the deputy mayor, the Gemeinderat did not vote for Kahr, but for a Social Democrat. In 2014, however, the Communists approved the city budget for 2015 and 2016, together with the Conservatives and the Social Democrats. In 2016, after the resignation of the Social Democratic deputy mayor, the Gemeinderat finally did elect Kahr as the successor.

However, after the elections of 2017, the conservative mayor formed a coalition with the FPÖ, a decision with important implications for the KPÖ. Not only did this new legislative majority elect a politician from the radical right as deputy mayor, more crucially, ÖVP and FPÖ deprived the Communists of controlling the housing department, now also in the hands of the FPÖ. Devoid of the issue they have long ‘owned’, Kahr is now in charge of traffic and public transport, while a new Communist member of the city government, the young teacher Robert Krotzer (born in 1987), is now responsible for the health department. Already before these challenging new agendas, key figures of the party had expressed their concerns about constraints such as the hegemony of austerity, the financial tightening of the municipalities (Parteder Reference Parteder2013) and the rising salience of immigration as a political issue, dominated by the claims of the radical right. While in all likelihood the KPÖ will remain an important player in the local polity of Graz in the foreseeable future, once again its politicians have to find new ways to reach their goals under difficult circumstances.

Conclusion

As this article has shown, the ‘curious success’ (Kuhn Reference Kuhn2013) of the KPÖ Graz can be explained by several aspects of the local ‘political opportunity structure’ (the ‘external supply-side’) in Austria and the strategic decisions of the party leadership (the ‘internal supply-side’). Most originally, the Communists managed to ‘own’ the issue of housing, focusing on it from the 1980s, by connecting it to their broader critique of capitalism. This decision was far from inevitable, as can be seen from the development of many other RLPs at that time. Similarly, the system of proportional government was crucial for the party’s ultimate take-off: With barely 8 per cent in the election of 1998, the party could appoint a member of the city government without the need to form a coalition. This unique feature of the Austrian local polity allowed the KPÖ Graz to govern without bearing responsibility for the actions of other governing parties.

In addition to the inherent merit of explaining the electoral success of the KPÖ Graz, my research adds to the renewed interest of party politics scholars in European RLPs by offering an analysis of a least likely case that contradicts most findings about the conditions of their electoral success: Even without a strong historical legacy and with strong electoral competition, a governing communist party in Western Europe can still, to some extent, gain votes and pursue policy.

Despite the lack of studies on this aspect, scholars have regularly acknowledged the importance of analysing how RLPs perform at the subnational level. Some point to the possibility of a slow rise through ‘strong local presence’ and creating ‘a national backbone’, as in the case of the Dutch Socialist Party (March Reference March2011: 129).Footnote 2 Others understand the subnational arena as a ‘training ground’ (Ştefuriuc and Verge Reference Ştefuriuc and Verge2008: 156) for national government participation, or at least as ‘an important tool in generating state-wide legitimacy’ (Hough and Verge Reference Hough and Verge2009: 52), as in Germany and Spain. However, these outcomes are unlikely in the case of Austria: here, the Styrian and the national branches differ in policy and strategy. The Styrian branch rejects EU membership and, correspondingly, the national party’s membership in the Party of the European Left (EL) – pointing to a widespread cleavage within European RLPs more generally as some significant exponents have refused to join the EL (Dunphy and March Reference Dunphy and March2013). Both at the national level in Austria and in Vienna, Communists have recently focused on running on ad hoc platforms with other minor parties – without electoral success, however. While there, high electoral thresholds provide important barriers, the local polities of other major Austrian cities are similarly open as the one in Graz – but electoral success by the KPÖ has been rare in those places too. With hardly any exceptions, Communist activists outside Styria have not been able to develop strategies that take advantage of polity features similar to those in Graz.

Future research on RLPs would benefit from a closer look at the many different paths subnational RLP branches take and how these developments relate to national performance. When are governing RLPs at the subnational level policy-takers and when are they policymakers? How is national performance related to learning, or not learning, from subnational experiences? And more generally: how does agency – that is, party strategy – influence outcomes? These questions point to the need to study the actions of RLPs in depth, both of those that prosper and those who fail. For the RLP family in particular, broadening the geographical scope and comparing experiences in Europe with those in Latin America might offer particularly interesting insights. What explains the sharp differences in electoral performance and policy output of RLPs in those regions? How is historical legacy relevant to their rise and fall? And how does the political economy of both continents and their individual states interact with the fate of RLPs? Despite the importance of such questions, however, the contemporary lack of success of many RLPs in Western Europe should not be reduced to structural reasons alone. Even more so in times of the Great Recession and high electoral volatility, we should also focus on the particular strategies of RLPs. The case of the KPÖ Graz shows that agency can make a significant difference.

Acknowledgements

Versions of this paper were presented at the ‘Special SCOPE 2015 pre-conference workshop on social movements to honour the work of Professor Donatella Della Porta’ in Bucharest, Romania (May 2015), at the GCAS Conference in Athens, Greece, (July 2015), and at the Austrian Day of Political Science in Salzburg, Austria (November 2015). I especially thank Donatella della Porta, Luis de Sousa, Jack Goldstone, Swen Hutter, James Jasper, Hans-Peter Kriesi, Dieter Reinisch (with whom I also conducted 10 of the interviews), and Julia Rone for their valuable feedback. Even more, I thank all the interviewees for their time and their illuminating answers.