Introduction

Kurds have often struggled with central governments to gain the most basic rights. At times, they have stepped forward and have tried to set up an independent territorial state of their own. This is most evident in Iraq. The Kurds of northern Iraq established a de facto state, and the Syrian Kurds declared an interim region of self-rule amidst the civil war that was then underway in the country.

As the now largest stateless nation in the world, the Kurds are entering into a new era due to the chaotic developments in their countries, especially in Syria. Kurds have long shown a strong inclination to be an independent state in the region. This trend has been abundantly clear especially in the southern part of Kurdistan, north of Iraq. Ismail Agha Simko's armed rebellion was the first serious attempt to create an independent Kurdish state in the eastern part of Kurdistan in the early 1920s (Yildiz, Reference Yildiz2004: 7), but the only independent Kurdish state was the short-lived Mahabad Kurdish republic (1945–46).Footnote 1 Also, Sheik Mahmoud al-Hafid fought for a Kurdish homeland in the early twentieth century in Sulaimaniya, but his small kingdom collapsed following the war with the British forces. Sheik Mahmoud was captured and exiled to India. Under the Treaty of Sèvres (10 August 1920), particularly Article 64, Kurdistan was granted independence (Yildiz and Muller, Reference Gunter2008: 7), but this treaty was not ratified by the signatory countries and Kurdish autonomy again reverted to dream status. The unfulfilled agreement was replaced by the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, with no mention of a Kurdish state. Kurdistan was divided between Turkey, Iran, Syria, and Iraq, although within those states Kurds inhabit an area of significant strategic importance.

The Kurdish self-rule region in Syria is located close to the Turkish and Iraqi borders. The present study aims to investigate the status of Kurdish self-rule in international law, and the long path ahead toward recognition of Kurdistan as a state in international law. This study also addresses the differences and similarities of the Syrian Kurdish situation with the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in Iraq. Though having endured some hard stages through the centuries, unlike the Kurds in Iraq, the Syrian Kurds face a long and uncertain path ahead if they are to become a nation-state. Also, unlike their Iraqi counterparts, they have not gained autonomy under the Assad regime. The KRG is now preparing to declare itself a state since it has met most of the requirements in international law. Recent developments triggered by the rise of the ‘Islamic State of Iraq and Al Sham’ (ISIS) terrorist group, its attacks on Kurdish cities and the resistance of the peshmarga (Kurdish armed forces), and withdrawal of the Iraqi army in the face of this threat, have created conditions that may help Iraqi Kurds achieve independent statehood. Recently, they were subject to systemic discrimination and repression, including denial of full Syrian citizenship. This situation arose in Iraq and Syria as a result of the decision made by French and British powers after the Great War to divide the Kurds between four countries, whereby they became the largest nation in the region without state.

What is happening in Syria has become complicated because the Assad regime left Kurds to themselves to muddy the situation of the 2011 uprising. Since the beginning of the uprisings in March 2011, the Kurds maintained a neutral stance, declaring that they would act neither with the regime nor with the opposition, and then, after a while, the Kurdish parties declared the self-rule region and replaced the Syrian flags with their own and took charge of state institutions.

Kurdistan

The Turkish Seljuk prince, the Saandjar, used the term ‘Kurdistan’ for the first time in the twelfth century upon the creation a province of that name (Yildiz, Reference Yildiz2004: 11). Currently, there is a Kurdistan province in the west part of Iran. According to the Sykes–Picot Agreement in 1916, Britain, France, and Russia divided the Kurdish territory between Iran, Turkey, Iraq, and Syria (Figure 1), including Turkey to the north, Armenia to the northeast, Iraq to the south, and Iran to the east. Even so, Kurdistan as an entity has appeared on some maps since the sixteenth century (McDowall, Reference McDowall2000).

Figure 1. Distribution of Kurds in the Middle East, www.britannica.com/topic/Kurd/images-videos/Areas-of-Kurdish-settlement-in-Southwest-Asia/6304

The Kurds

Kurds are a non-Arabic and largely Sunni Muslim people with their own language and culture, who live in the contiguous areas of Turkey, Iraq, Iran, Armenia, and Syria – a mountainous region of southwest Asia. As of the seventh century and then after the Islamization of this part of world, the Arab Muslims referred to the people of the region as ‘Kurds’ (Gunter, Reference Gunter2009). They have lived there for about 4,000 years (Anderson and Stansfield, Reference Anderson and Stansfield2004), an ancient Indo-European people, ethnically and linguistically distinct from their neighbors. Their language is divided into several dialects. They are believed to be descended from the Medes, a people who are mentioned in the Old Testament of the Bible (Yildz, Reference Yildiz2005: 32).

As the largest stateless nation in the world (Yildiz and Taysi, Reference Yildiz and Taysi2007: 1), their population is between 35 million and 40 million.Footnote 2 A diaspora has spread Kurds to the United States and the former Soviet Union (Kreyenbroek and Sperl, Reference Kreyenbroek and Sperl1992),Footnote 3 Lebanon (O'Shea, Reference O'Shea2004), Europe (Hassanpour, Reference Hassanpour1996), and also the northeast province of Khorasan, Iran (Gunter, Reference Gunter2009). But the highest numbers reside in Turkey (Kreyenbroek and Sperl, Reference Kreyenbroek and Sperl1992: 15). Although it is generally accepted that they constitute the largest nation without a state in the world, there are no official population statistics that document this.

Kurds in Syria

The first comprehensive studies of the Kurds in Syria were undertaken in the 1990s (Tejel, Reference Tejel2008).Footnote 4 These focused on their status as a ‘minority’ in the legal structure and political system of the ruling government. They have been regarded as a peripheral group.

The borders of modern Syria were determined by the Sykes-Picot Agreement (1916), the Cairo Conference (1920), and the Treaty of Lausanne (1923). Accordingly, the western (‘Rojava’) part of Kurdistan came under a French mandate after World War I.

The current settlement of the Syrian Kurds was agreed by France and Turkey through an accord signed in Sèvres, France; the Treaty of Sèvres. Kurds comprise Syria's largest non-Arab ethnic minority with 3.5 million to 4 million people, or about 15% to 17% of the total population of 23 million.Footnote 5 They are located mainly in the northeastern Hasake region and along the Turkish border as far as Afrin in the northwest, and in Kobanê (Arabic: Ayn Al-Arab). Also, they are a minority in the cities of Aleppo and Damascus. The majority of Syrian Kurds speak the Kurmanji dialect, which is also spoken in Iran, Turkey, and northeastern Iraq. Most of them are Sunni Muslims, although they are living peacefully alongside Yazidis who are ethnically Kurdish.

The Syrian state has long denied the Kurds basic human rights. A central government decree (no. 93) of 23 August 1962 ordered a census of the population in Jazira (Cizîre, meaning island), which was carried out in November that year. In 1962, an exceptional census stripped about 120,000 Kurds of their Syrian citizenship,Footnote 6 and about 20% of Syrian Kurds lost their citizenship. The state authorities claimed that 80% of the Syrian Kurds were ‘true’ Syrians and they were deemed eligible for new identification cards, and the remainder were illegal immigrants from Turkey. Surprisingly, some members of families were considered Syrian nationals and others were not. In certain households, fathers held nationality status while some or all of their children did not. Those Kurds who did not take part in the census became maktum, meaning unregistered, or were registered as foreigners. Many became stateless under international law. The foreigners were given a simple white piece of paper on which was written: ‘His/her name was not on the registration lists of Syrian Arabs specific to Hasaka.’Footnote 7 Syria had about 154,000 foreigners and 160,000 unregistered persons.Footnote 8 These stateless Kurds lived in a legal vacuum and were deprived of human rights: linguistic, political, and other human rights. Unregistered persons lost rights to their property, which were forfeited to the state. The Kurdish names of towns and villages were replaced with Arabic ones. Property ownership and transfer in the Kurdish region and many other rights were restricted.Footnote 9 The Arabs launched a media campaign under the slogans: ‘Save Arabism from Jazira’ and ‘Fight the Kurdish Menace’. They referred to Kurds as a ‘foreign group’ (Tejel, Reference Tejel2008: 52).

Kurds in Syria joined an autonomist movement in the Jazira region in 1936 called the ‘Kurdish-Christian bloc’ (ibid., 30), which led to the summer uprising of 1937 during the French mandate. A consequence of the uprising was the creation of the autonomous administrations for the Jabal Druze, the territory of Latakia and Jazira in 1939; but, despite government promises, this period ended with Kurdish demands unmet. In a study of 12 November 1963 by Lieutenant Muhammad Talab al-Hilal, a former Secret Services officer in Hasaka, the Kurds’ existence as an entity was brought into doubt on the basis that they had neither ‘history nor civilization; language nor ethnic origin’. The Kurdish Democratic Party of Syria (KDPS – Partiya Demokrat a Kurdî li Sûriyê, PDKS) was established in 1957.Footnote 10 Masoud Barzani, the current president of the KDP and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in the North of Iraq played a significant role in the well-establishment of the KDP. Its main objective was recognition of the Syrian Kurds as an ethnic minority. The KDPS leaders were arrested and charged with separating in 1960.

On 13 November 1970, general Hafiz al-As'ad, led an aggressive coup. In the Syrian Constitution of 1973, Syria was proclaimed a republican democracy and is presided over by the Ba'athist Party; that Constitution and the Ba'ath Party are still in existence, continuing to disadvantage those ethnic and religious groups who challenge the unity of Syria. The Ba'ath Party also seeks to deny the very legitimate existence of the Kurds, and the state increased its repressive policies. Similar to the regime's policy attitude towards Israel, it was supposed that ‘there is no difference between them and Israelis, for Judistan and Kurdistan, so to speak, are of the same species’ (Tejel, Reference Tejel2008: 60). They posed a ‘danger’ to the Arabs. The government started: (1) the displacement of Kurds from their lands to the interior; (2) the denial of education; (3) the handing over of ‘wanted’ Kurds to Turkey; (4) an anti-Kurdish propaganda campaign; (5) the implementation of a ‘divide-and-rule’ policy against the Kurds; (6) the colonization of Kurdish lands by Arabs; (7) the militarization of the ‘northern Arab belt’ and the deportation of Kurds from this area; (8) the denial of the right to vote; and (9) the denial of citizenship (Tejel, Reference Tejel2008: 61). After creating an ‘Arab belt’, the Arabization process was begun in 1973. Almost 4,000 Arab families were settled in Kurdish regions. The teaching of the Kurdish language was prohibited.

In the 1980s, as the opposition movement (Islamic resurgence movement) grew among Syrian Arabs, As‘ad put an end to forced transfers from Jazira, and Kurds were given high military positions and were used to suppress the 1980 and 1982 Muslim Brotherhood revolts. However, before the death of Hafiz al-As‘ad, Resolution 768 was approved in May 2000, ordering the closure of all stores selling cassettes and videos in the Kurdish language and prohibiting the use of the language in meetings. The registering of children with Kurdish names was also restricted. Between 2001 and 2002, repression of Kurds grew, and hundreds of Kurds, particularly stateless individuals, fled to Europe. The Kurds would have paid refugee smugglers $3,000–4,000 for adults and $1,700–2,000 for children to go from Syria to Europe and America. This process has not ended yet.

During the Hafez and Bashar Assad regimes, Kurdish status remained unchanged until the 2011 uprising. Fearing regime repression, Kurdish political parties were reluctant to fight against Assad's army because they had experienced the brutal repression of the 2004 uprising in Qamishli.Footnote 11

The Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK)Footnote 12 was supported during the presidency of Hafez Assad. As a result of developments in Turkey–Syria relations in early 2000s, the PKK lost the support of the Syrian regime, which in turn led to the creation of a new party, the Democratic Union Party (Partiya Yekîtiya Demokrat, PYD) formed by PKK members in 2003. During the 1980s and 1990s, the PKK was popular among Kurds in Syria as it attempted to assert a Kurdish identity; for example, it encouraged the use of the Kurdish language in meetings and at festivals. Hafiz al-As‘ad died on 10 July 2000 and his son succeeded him as head of government. After the invasion of Iraq by US-led forces in 2003 and the creation of a de facto autonomous region in the north by Iraqi Kurds, the Syrian regime became concerned.

The 12 March 2004 a new era began for the Kurds in Syria. During a football match in the town of Qamishli between the local Kurdish team and Dayr al-Zor, offensive words were exchanged between fans of the two sides, which turned into a riot. Riding around the town in a bus, the fans of Dayr al-Zor chanted slogans insulting the Iraqi Kurdish leaders, Barzani and Talabani, while displaying pictures of Saddam Husain. Fans of the Kurdish team responded with chants praising President George Bush. A battle broke out between them. Security forces opened fire, which resulted in the death of six Kurds. This led to rioting throughout Qamishli. The demonstrators were suppressed in an unprecedently brutal way. In a few Kurdish towns, statues of Hafiz al-As‘ad were destroyed, as Kurds were inspired by the fall of Saddam Hussain in Iraq.

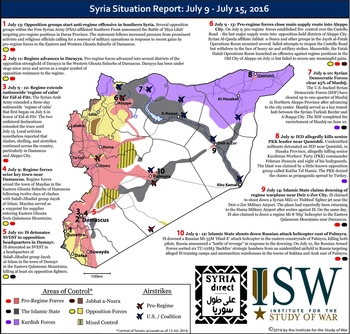

The 2011 uprising further changed the situation. Anti-regime demonstrations began in Arab cities in April 2011. Immediately, the regime ordered citizenship to be granted to thousands of Kurds in the Hasake province. Anti-regime demonstrations increased, but the PYD tried to maintain its moderate stance since its leadership believed this could lead to Kurdish self-rule and they would control their affairs. The Kurdish city of Kobanê was subsequently seized by Syrian Kurds on 19 July 2012 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Kurdish regions and controlling northern border in Syria

Syria Situation Report: By Chris Kozak, July 9–15, 2016, www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/syria-situation-report-july-9-15-2016.

Russian Airstrikes in Syria: By Genevieve Casagrande, May 13 - June 2, 2016, www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-airstrikes-syria-may-13-june-2-2016.

Syria Situation Report: April 27, updated 6 May 2016, www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/syria-situation-report-april-27-may-6-2016.

Syria and its Neighbours, www.syria.chathamhouse.org/?gclid=CPKTiLCQ1MwCFUIfhgodvHoEJg.

Syrian Civil War Control Map, updated April 2016, www.polgeonow.com/search/label/syria.

Control of Terrain in Syria, updated 23 December 2015, Institute for the study of War, www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/control-terrain-syria-december-23-2015.

Battle for Iraq and Syria in maps, updated 23 December 2015, www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-27838034.

Who Has Gained Ground in Syria Since Russia Began Its Airstrikes, updated 29 October 2015, The Carter Center (areas of control); Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (some targets), and IHS Conflict Monitor, www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/09/30/world/middleeast/syria-control-map-isis-rebels-airstrikes.html.

The regime's twisted policies toward the PYD provided an opportunity to establish a local government. The PYD founded the People's Council of Western (‘Rojava’) Kurdistan (PCWK) on 12 December 2011, with 320 members.Footnote 13 The PCWK provides social services. The PYD also founded People's Local Committees (PLCs), in which each committee would be locally responsible. The PLCs act under a Central Coordination Committee, which was established in 2007, composed of 24 members comprising the heads of each department.

Self-rule interim administration in the ‘West of Kurdistan’, ‘Rojava’

Although there are other parties that have close ties with Masoud Barzani as the president of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in Iraq and head of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), the Democratic Union Party (Partiya Yekîtiya Demokrat, PYD) is the main Kurdish party in Syria. It was founded in 2003 and is headed by Salih Muslim Muhammad. Hundreds of its members were arrested and many of its leaders executed by the Syrian Ba'ath regime. The PYD has had a major role in the Syrian conflict and is supported by the majority of Kurds. Soon after the 2011 uprising broke out, the PYD, which had been encamped with the PKK in northern Iraq's mountains, returned to Syria, collecting its fighters. In July 2012, taking advantage of the regime's security forces’ partial withdrawal from Kurdish areas, the PYD took control of at least five Kurdish strongholds, replacing Syrian flags with its own. After declaring an autonomous region, there were clashes between PYD fighters and other opposition armed groups because the part military wing, YPG (Yekîneyên Parastina Gel, the People's Defence units) was reluctant to confront the Assad forces. This force controls the Kurdish regions and the areas bordering the KRG and Turkey. It also provides security for government buildings and maintains checkpoints in cities and on the roads. The Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) and the Kurdish National Council (a group of 15 Syrian Kurdish groups in Syria, KNC) proceeded to found the Kurdish Supreme Committee (KSC) to control the Kurdish region in Syria. This is the governing body of Syrian Kurdistan.

On 19 July 2012, the YPG besieged government buildings in the Kurdish city of Kobanê, and the government forces were forced to leave without a fight. Similar developments occurred in Efrîn and Cizrê. The central government forces showed no resistance. It is not clear why the regime allowed the PYD to control the Kurdish region and cities were handed over to the Kurds, but some believe that Assad withdrew from northern Syria and gave the north to the PYD in order to counter Turkish influence in northern Syria. Assad did not want to fight several fronts at the same time. Although the Kurds and Syrian army are jointly fighting ISIS on some fronts, the Syrian government is still opposed to any Kurdish stability – for example, the Syrian army attacked a Kurdish checkpoint and their forces in Hasake on 19 May 2014. The Syrian government did not back the Kurds, but preferred to remain neutral.

To bolster security in the region, the Kurds in ‘western (‘Rojava’) Kurdistan’ held meetings to maintain stability. These local meetings led to a wider conference convened on 12 November. Delegates of 35 parties and civic and social organizations attended the conference, including Kurds, Arabs, and Assyrians.

Having control of Kurdish regions by the YPG and YPJ (Yekîneyên Parastina Jin, the Women's Protection Units), they approved a federal Constitution for ‘Western Kurdistan’ under which three autonomous cantons were established. A day before the second Geneva Conference on Syria (to which Kurds were not invited), the Kurds declared the Kurdish cantons: Cizîre (east) on 21 January 2014, Kobanê (center) on 27 January 2014, and Efrîn (Afrin) (west) on 29 January 2014. In June 2015, the town of Girê Spî was recaptured from ISIS by the YPG militia with help from US-led air strikes, and on 21 October 2015 was declared officially as a new canton which connected Kobanê and Cizîre.

After withdrawal of Syrian central government forces from the Kurdish regions, the Kurds have established a self-rule administration. The PYD announced the Kurdish Constitution on 21 July 2013Footnote 14 in which Syria is an independent country having a democratic parliament and federal system, and ‘Western Kurdistan’ is a part of the country.Footnote 15 The Constitution has 96 articles. The Kurdish Center for Legal Studies and Consultancies published its draft on 21 December 2013 in Erbil (Hewlêr).

In the preamble of the Constitution, it provides that:

We, the people of the Democratic Autonomous Regions of Afrin, Jazira and Kobanê, a confederation of Kurds, Arabs, Syrics, Arameans, Turkmen, Armenians and Chechens, freely and solemnly declare and establish this Charter. (Preamble of the Constitution of Roja va Cantons in Syria)

Also, under the preamble of the Constitution, the Kurds declare the Kurdish regions:

autonomous Regions, unite in the spirit of reconciliation, pluralism and democratic participation so that all may express themselves freely in public life. In building a society free from authoritarianism, militarism, centralism and the intervention of religious authority in public affairs, the Charter recognizes Syria's territorial integrity and aspires to maintain domestic and international peace.

The cantons have been founded on the principle of local self-government (Constition of the Rojava, Article 8). Article 12 has clarified that the Autonomous Regions are a part of the future decentralized federal governance in Syria.

The People's Protection Unit (YPG) is the only military force in the regions (Constition of the Rojava, Article 15). Surprisingly, the Constitution has not declared any religion as an official religion of the Cantons.Footnote 16

The ‘Rojava’ Constitution has confirmed the right of inhabitants of Kurdish regions to self-determination:

It protects fundamental human rights and liberties and reaffirms the peoples’ right to self-determination. (Preamble of the Constitution of the Rojava Cantons in Syria)

They chose Kurdish, Arabic, and Syriac as the official languages. The capital of the self-rule administration in the Cizîre Canton is the city of Qamishli. It has two deputies and 22 ministers, including those for foreign affairs, defense, and justice, and the heads of each of the local canton governments. Male and female co-leaders operate the council of ministers in each government, representing local diversity, with three deputies. It seems that they are inspired by the pluralistic Swiss governing model. The PYD asserts that a federal Western (‘Rojava’) Kurdistan would be a part of a decentralized Syria in the future. The Kurds of Syria are seeking western support to recognize their administration and at the same time are trying to develop further their own system of administration. Their latest effort was the declaration of a ‘social contract’, which established democratic autonomy for ensuring social justice. On the basis of the ‘social contract’, the Kurdish cantons are part of the Syrian state, and the habitants of the canton of Cizîre include Kurds, Arabs, Assyrians, Armenians, and Chechens, alongside Yezidis, Muslims, and Christians (Constitution of Rojava, Article 3). Also, it made it clear that the interim legislative assembly is the highest representation of the cantons. The Kurdish administration model is based on the three pillars of the canton and the federal system, the legislative assembly, and administration and justice, including all ethnics and religions. The Kurds insist repeatedly that they are friendly to everyone, and just want to have free and democratic lives. Turkey's pro-Kurdish Peace and Democracy Party (BDP) deputies and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in the north of Iraq welcomed the declaration of the autonomous administration, and also its parliament formally recognized the cantons on 15 October 2013.Footnote 17

For the past year, in order to protect the Kurdish cities, the YPG (Yekîneyên Parastina Jin, the Women's Protection Units), with support from Turkey, have been involved in fighting against regime forces, the Al-Qaeda groups,Footnote 18 the Al-Nusra Front, and particularly ISIS.Footnote 19 These terrorist groups are against the Kurds, Assyrians, Arabs, and Armenians, and use brutal ways to occupy their cities. ISIS has founded an Islamic ‘caliphate’ in Iraq and Syria having a heavy military presence in the Kobanê canton and surrounding areas.Footnote 20 After a long debate on obtaining permission from Turkey to cross its border, 150 peshmerga fighters from the north of Kurdistan (by approving the KRG parliament) arrived in Kobanê with heavy weaponry to back the YPG and YPJ.Footnote 21 The second group of peshmerga arrived in Kobanê on 2 December 2014.Footnote 22 At the same time, US-led airplanes were bombing ISIS targets near Kobanê. Also, around 200 fighters from the Free Syrian Army (FSA) entered the city to help the Kurds. Kobanê has now become an international symbol of resistance in the battle against the terrorists. The YPG has controlled Arabic Tal abiaz), Tal Hamis, and Tal Barrak.

The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG)

Following the events of 9/11, the US and coalition forces attacked Iraq on 19 March 2003. In 1988, the main Kurdish parties established the first National Front of Kurdistan (Yildiz, Reference Yildiz2004: 56), which is the origin of the KRG. After the Second Gulf War, two Kurdish parties, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), established a Kurdish region in northern Iraq (Stansfield, Reference Stansfield2003: 27). After the defeat of Saddam Hussein in Kuwait, Kurdish forces seized control of many Kurdish cities in the north, including Kirkuk on 20 March 1991 (Yildiz, Reference Yildiz2004: 13). However, they were forced out of the Kurdish area by the Republican Guard. Almost 20,000 Kurds were killed, over 100,000 went missing, and around 2.5 million took refuge in Turkey and Iran (ibid.).

The UN Security Council passed Resolution 688 on 5 April 1990, demanding that the Iraqi government end the suppression of its citizens, particularly the Kurds. A no-fly-zone over a large part of northern and southern Iraq was established by the US and British governments in 1991. On 20 October, Saddam's forces withdrew from the north (Erbil, Dohuk, and Sulaymaniyah) (ibid.).

On 19 May 1992 and under the observation of human rights organizations, Kurdish parties held elections (National Assembly and presidential); the most democratic elections in the Middle East with participation of unprecedented numbers of people. Minorities received seats in the new parliament (ibid.: 15). A de facto state, the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) came into existence. On July 1992, its first cabinet was formed. Judicial power and a Supreme Court in the KRG were established under Law No. 44 (ibid.: 30). The governments treat the KRG as a de facto ‘state’, but no country recognizes it as a state. Iraq's ConstitutionFootnote 23 was approved in the 15 October 2005, referendumFootnote 24 which states: ‘The system of government is a democratic, federal, representative, parliamentary republic’ (Constitution of Iraq, Article 1).

Arabic and Kurdish were given as the official languages (Constitution of Iraq, Article 4) and Turkomen (or Turkmen) and Assyrian were also made official in the provinces (Constitution of Iraq, Article 4(4)). Five Kurdish governorates were recognized (Erbil, Kirkuk, Sulaymaniyah, Dohuk, and Halabja). The new constitution recognized the Kurdish region as a federal entity (Constitution of Iraq, Article 116) with the Kurdistan Region Presidency, and the Kurdistan Parliament.Footnote 25 It has the right to establish internal security forces (Constitution of Iraq, Article 117(5)) and also will have an ‘equitable share of the national revenues sufficient to discharge its responsibilities and duties’ (Constitution of Iraq, Article 117(3)).

The Kurdish government is composed of 22 ministries and four departments,Footnote 26 and is based in Erbil, the capital of the Kurdistan Region. On 24 June 2009, the Kurdistan draft constitution was approved by the KRG and was passed by the Kurdistan Parliament on 26 June 2009, but it has not been voted on in a referendum. Using terms such as ‘our people’ and ‘nation’, the preamble to the Kurdistan constitution suggests that Kurdistan demands to be an independent state and seeks equality for all (Preamble of the Constitution of the Kurdistan Region).Footnote 27 The independence of the Kurdish region has been reflected through Article 1:

It is a democratic republic with a parliamentary political system that is based on political pluralism, the principle of separation of powers, and the peaceful transfer of power through direct, general, and periodic elections that use a secret ballot. (Constitution of the KRG, Article 1)

According to its constitution, the Kurdistan region had the power of granting asylum (Constitution of the KRG, Article 19(19)), but this is among the powers of the federal government (Constitution of Iraq, Article 107).

The right to leave the federation has been reserved if the central government departs from the federal model; the right of the Kurds to self-determination (Constitution of the KRG, Article 8).

Self-determination

The right to self-determination has been a controversial status in international law. Martti Koskenniemi has recognized two forms of self-determination: a ‘good’ form as a democratic instinct and a less benign form as an isolationist instinct (Koskenniemi Reference Koskenniemi1994). Since World War II, it has been used by most new member states of the United Nations. The Covenant of the League of Nations did not mention any reference to the right to self-determination (Crawford, Reference Crawford2006) but other international legal documents have declared it in their provisions, as the UN Charter in Article 1 (2) declares it: ‘To develop friendly relations among nations based on the respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples.’

Also, the International Covenants on Human Rights (ICCPR, 1966) in Article 1 reaffirms all peoples’ right to self-determination and through it people can determine their political status freely. The General Assembly of the United Nations in the 1952, Resolution 637A (VII), wanted state members to ‘uphold the principle of self-determination of all peoples and nations’. Today, many people within sovereign states refer to this resolution to confirm their right to establish a state of their own. The right to self-determination has become the source of conflicts within the international community, such as the cases of Quebec in Canada, Kosovo, Kurdish Regional Government in Iraq, Catalonia in Spain, and as many as 140 movements which have demanded autonomy (Moris Reference Moris1997).

The Kurds’ right to self-determination, as well as statehood, was recognized in the Treaty of Sèvres (Article 62, 1920) (Yildiz, Reference Yildiz2004), and it was replaced by the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923 since Turkey dissented from it. The Treaty of Lausanne made no mention of Kurdish statehood (Gunter, Reference Gunter2008). After establishing a de facto Kurdish Government in the North part of Iraq by the Kurds in 2003, and the 2011 uprising in Syria, the Kurds in the south of Syria have exercised the right to self-determination and established a self-rule administration with a different model for controlling Kurdish regions.

Statehood and independence

The concept of statehood has been a main controversial issue in international law due to continuing decolonization since 1945 and as full membership in international organizations is usually dependent on statehood. There are no viable and subtle rules in international law for assessing a community is a State. As Crawford (Reference Crawford1976) stated it is ‘not “simply” a factual situation but a legally defined claim to govern a certain territory’. There is generally no accepted and satisfactory contemporary legal definition of statehood and legal documents have failed to codify the rules relating to statehood and ‘statehood does appear to be a term of art in international law’ (ibid.). Even the International Law Commission has been reluctant to present a comprehensive definition of statehood, but if it is a legal concept, there must be the criteria for statehood.

To be a new nation-state, communities which claim supremacy within existing states, must qualify under the international legal criteria of statehood. The basic criteria for statehood has been laid down in Article I of the Montevideo Convention 1933, which is most often cited, in particular its section on ‘the Rights and Duties of States’.Footnote 28 The Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States in Article 1 proposes a ‘state’ as having: ‘(1) a permanent population; (2) a defined territory; (3) government; and (4) capacity to enter into relations with the other states’. The Kurds in Iraq have already qualified the requirements to be as a ‘state’ according to the Montevideo Convention. Above all, ‘Independence is the central criterion of statehood’ (Crawford, Reference Crawford1976). Judge Huber stated:

Sovereignty in the relations between States signifies independence in regard to a portion of the globe is the right to exercise therein, to the exclusion of any other State, the functions of a State. The development of the national organization of States during the last few centuries, and, as a corollary, the development of international law, have established this principle of the exclusive competence of the State in regard to its own territory in such a way as to make it the point of departure in settling most questions that concern international relations. (Island of Palmas case, the Netherlands Vs the United States which was heard by the Permanent Court of Arbitration, 4 April 1928)Footnote 29

Lack of independence can lead to the point where the entity claiming recognition is not a State, because although independent it is acting under the control of another State, so that entity here is an agent rather than independent. So the criterion of independence operates as the basic element and ‘as an initial qualification’ (Crawford, Reference Crawford1976).

Sovereignty

Sovereignty and independence are used interchangeably but they are distinct. The term ‘independence’ is ‘the prerequisite for statehood’, and ‘sovereignty’ is the legal incident. The term ‘sovereign’ is also used in politics to indicate ‘actual omnicompetence with respect to internal or external affairs’ (ibid.). Other criteria have been proposed and also used for statehood, such as permanence, willingness and ability to observe international law, a certain degree of civilization, recognition, legal order.

Crawford restated that ‘recognition is not strictly a condition for statehood’. In international law, an entity which has not been recognized as a State but has qualified under the requirements for Statehood would be treated as a non-recognized State. In other words, States are free to recognize the entity claiming statehood, though it may play a crucial role in particular cases, such as the Vatican and Taiwan.

Autonomy

The concept of autonomy is something in between the concept of ‘non-self-governing territory’ and an ‘independent’ State. Thus, it is short of independence. The people in an autonomous region have control over their social, cultural, and economic affairs (Sohn, Reference Sohn1980). To manage these affairs, the territory must have its own government without other interfering governments. The autonomous government would be composed of all three basic branches: legislative, executive, and judicial, but the central government ‘would retain powers in the field of foreign relations and international security’ (ibid.).

Kurdish statehood

The Kurdistan regional Government (KRG) in Iraq has met the legal criteria, but has not declared independence yet. Since it does not have a predictable form, in order to study the method of exercising the right to self-determination, each case should be taken into account separately. Syrian Kurds have a long road ahead to be recognized as a state. Unlike the KRG, which has met the Montevideo Convention's requirements, Kurdish cantons in Syria, though popular with inhabitants of Kurdish regions, have not hosted any foreign officials but by declaring a ‘federal democratic system’ in the Jazira, Kobanê, and Afrin cantons in northern Syria on 17 March 2016,Footnote 30 they sought to prove themselves as a self-run de facto entity ‘in the fields of economy, society, security, healthcare, education, defense and culture’, although some believe that this complicates UN-backed peace talks among the opposition and Assad's government. This has made neighbouring countries displeased, especially Ankara and even Washington which has backed the Kurds in Syria. Though Russia insists and has demanded the presence of Kurds in Geneva, Turkey's ‘fear of Kurds’ has been the main opposition for their participation in the peace negotiations.

The self-rule regions can satisfy the first requirement of a state. Crawford (Reference Crawford2006) states that there is no rule on minimum limit of the population. The Kurdistan region in Syria is about 2.3 million. The states with populations of less than that and that have been recognized by the United Nations included Timor-Leste (East Timor) with 1,152,000, Bhutan with 766,000, Solomon Islands with 573,000, Luxembourg with 537,000, Iceland with 333,000, and Dominica with 72,00 (UN Data).Footnote 31

The Kurds in Syria have the recognized regions of Afrin, Jazira, Kobanê, and Girê Spî (Tel Abyad) as cantons and also as integral parts of the Syrian territory (Constitution of Rojava, Article 3B), but they have not been recognized by the Syrian central government or any other stateFootnote 32 in the international community. Even though the policies of the neighbouring states are not clear,Footnote 33 the parliament of the KRG has recognized them.Footnote 34

The main element to statehood is having a ‘government’ or an ‘effective government’ of internal and external affairs on its territory; ‘a basis for the other central requirement of independence’ (Crawford, Reference Crawford1976). International law defines ‘territory’ by ‘reference to the extent of governmental power exercised, or capable of being exercised’ (ibid.). Thus, it is a precondition for having international relations. The ‘government’ has two aspects: ‘the actual exercise of authority, and the right or title to exercise that authority’ (ibid.). Kurdish self-rule in the four cantons operates as a government, and Damascus has no control over it. Currently, an uninterrupted stretch of 400 km (250 miles) is being controlled effectively by the Kurds along the Syrian–Turkish border, from the Euphrates river to the frontier with Iraq. They also have the Afrin in the North-western border. The PYD runs the ministries and Kurdish YPG militia serves as the security force in Kurdish regions. The autonomous government can be run by a man or a woman with 22 ministers appointed by the parliament. The self-rule government is operating within a democratic confederalism framework involving the Legislative Assembly, Executive Councils, High Commission of Elections, Supreme Constitutional Courts, Municipal/Provincial Councils (Constitution of Rojava, Article 4). It intends to ‘implement a framework of transitional justice measures’ (Constitution of Rojava, Article 14).

Every State is ‘an original foundation predicated on a certain basic independence’ (Crawford, Reference Crawford1976) and the Montevideo formula administered this by ‘capacity to enter into relations with other States’. Before being recognized as a state, an entity must already have the capacity to enter into relations with other states. Whether the PYD can satisfy this requirement is not clear. The self-rule government has established a ministry of foreign affairs, and Salih Gedo has been appointed to it. The ministry aim is to ‘gain international recognition for cantons’, and to do this Kurds have met NGOs and social democratic and left parties in Europe, the Norwegian Foreign Ministry, and addressed the European Parliament in Strasbourg,Footnote 35 and Turkey's and Iraq's representatives. No state has recognized Rojava self-rule officially yet. Syrian Kurds lack foreign allies. Recently, the PYD has asked to open its diplomatic relations with Russia.Footnote 36 Since the first diplomatic mission to the city of Sulaymaniyah in the Kurdistan Region on 15 August 2015, it continued to expand the diplomatic network in Europe, and has opened representation offices in Moscow,Footnote 37 Prague, Stockholm, Paris,Footnote 38 and Berlin while seeking to open its mission in Washington.Footnote 39

‘Rojava’ self-rule interim government versus Kurdistan regional government and their status in international law

The KRG was established by the two main Kurdish parties, the KDP and the PUK in 1992 by the Kurdistan National Assembly.Footnote 40 Since the invasion by US-led forces of Iraq, and with the fall of Saddam Hussein's regime in 2003, the north part of Iraq has been controlled by the Kurds and recognized as a de facto state. The KRG is seeking to be recognized as a de jure state. It has met the qualifications required under international law. Comparisons will now be made with the democratic federal self-rule in ‘Rojava’ (northern Syria).

The KRG has had a long journey trying to establish a Kurdish state. The Kurds in south Kurdistan have been initiating efforts since 1922 (Yildiz, Reference Yildiz2004) and their recent de facto effort came out of an uprising led by Mola Mostafa Barzani accompanied by Jalal Talabani (Head of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan), which started in March 1961 in Iraq (Stansfield, Reference Stansfield2003). His son, Masoud is the President of the Kurdistan government. Recently, Masoud Barzani called for an independence referendum despite the numerous crises within his territory, though no timetable has been set for it.Footnote 41 There are also long controversial debates on extending the term of Barzani's presidency within Kurdish parties. Currently, peshmerge is fighting against ISIS along Kurdish borders in an attack-counterattack form. The Kurds recaptured Sinjar town from ISIS where thousands of Yezidis minority trapped in the mountain led to a massacre in August 2014 and ISIS was systematically slaughtering, enslaving and raping thousands. Recently, on 16 june 2016, UN human rights panel recognized it as Yezidis genocide that “amounts to crimes against humanity and war crimes”.Footnote 42 Since the withdrawal of Saddam's forces from the north, the PUK and the KDP, along with other parties, have controlled the region (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Kurds in the North of Iraq (July 2016)

Iraq Control of Terrain: By Emily Anagnostos, July 14, 2016, www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/iraq-control-terrain-july-14-2016

The ‘Rojava’ self-rule administration was established in January 2014 by the PYD on the eve of the Geneva II Conference (21 January 2014) on Syria, and ‘democratic federalism’ was declared on 17 March 2016. The Syrian uprising broke out in March 2011, and the Kurds in Syria went through many difficult stages under the ruling governments, but were not paid any attention by the rest of the world. The Kurds in both Iraq and Syria were under control of the Syrian Ba'ath regime, but the Kurds in Iraq have clearly showed their will against the government. The newly established Kurdish administration in Syria still has a long way to go to attract the world's attention, although many states have been surprised by its structure. Although the KRG administration's intention was to achieve the goal of independent statehood, the Kurds in Syria rejected the nation-state and this could be interpreted as a sign that they ‘don't want an independent State but autonomy within a democratic Syria’ (Aretaios, Reference Aretaios2015). They declared in their constitution that the Kurdish Autonomous Region is composed of three cantons in a ‘decentralized federal’ (Article 12) Syrian State, and the Charter recognizes ‘Syria's territorial integrity’ (preamble of constitution) and will remain an ‘integral part of Syria’, though this might be a tactical or a strategic move to achieve a greater goal – independence. The ‘Rojava’ self-rule needs other states’ support to maintain its stand. The KRG is experiencing its seventh cabinet since the first general election in 2005,Footnote 43 while ‘Rojava’ is still represented by its first cabinet. Over last decade, the Kurds have witnessed many improvements in health and education and infrastructure developments, though the KRG has achieved these using the central government's budget and recently through selling oil on the world market.Footnote 44 ‘Rojava’ has also used the sale of oil to improve its cantons.

The KRG's military wing, peshmerga Footnote 45 has achieved much since the beginning of the Kurdish uprising in Iraq, especially in fighting against ISIS. The PYD's armed forces, YPG has had an active role in controlling and guarding Kurdish cantons and their borders. The YPG and YPJFootnote 46 recaptured the Kobanê canton from ISIS militia after fighting for more than four months.Footnote 47 The KRG has dispatched 150 peshmerga to support the YPG. At the same time, US jetsFootnote 48 bomb ISIS bases in Kobanê.

The KRG has been recognized by the Iraqi Constitution,Footnote 49 but the Syrian central government has not recognized the ‘Rojava’ interim administration. The KRG has hosted many states and international organizations’ representatives, such as the Chief of Staff of the United States Army,Footnote 50 and also the US Secretary of State, the UK Foreign Secretary, and Turkish Prime Minister.Footnote 51 Erbil is now host to 40 diplomatic representations.Footnote 52 There is no evidence that any foreign representative has visited the ‘Rojava’ cantons yet. The KRG and the PYD have their own flag, which flies in the Kurdish regions.

The structure of administration in ‘Rojava’ differs from the KRG. Both regions experience diversity of ethnicities, religions, and cultures among their population, such as Christians, Yazedis, Alawites, Arabs, and Turks. Both governing structures have recognized the diversity and their rights to their language in their Constitutions.

Conclusion

It seems that ‘Rojava’ self-rule and the KRG have many differences. Although ‘Rojava’ is a new form of government in the Middle East, it has a long way to go before it is in a similar position to the KRG. It is a newly founded administration, which is seeking support and recognition. Rojava's foreign relations is young and inadequate compared to those of the KRG. Both Rojava and the KRG are now engaged in fighting ISIS though close to overcoming it. They should defeat it first and then struggle for recognition. Still, ‘Rojava’ is in the process of construction, and it has been isolated by the Syrian and Turkish governments and ignored by Western media and the West.

The Kurds in Syria have tried to establish a democratic government through a hybrid political system: federalism and the ‘rejection of the nation-state structure’. It seems that they do not want an independent state but autonomy within a democratic Syria. However, their counterpart in Iraq has the inclination to declare itself a new nation-state in the international community.

Both the PYD and the KNC (in Syria) are seeking autonomy, although they have different strategies. The KNC is close to the Arab opposition and has a close relation with the KRG in Iraq, but the PYD is linked to the PKK. The PYD and the KNC signed an agreement on 12 July 2012 in Erbil. The PYD and the KNC are running Kurdish areas. They along with other Kurdish parties are seeking autonomy, but with different views. All the Kurdish parties are making any effort for the Kurdish population to be recognized as a part of Syria. The Kurds want their rights to be secured in Syria's Constitution. Declaring the Kurdish areas self-rule is a milestone in the history of Syrian Kurds.

The YPG and YPJ defended Kobanê in a bloody fight – a strategic city of the Jazire canton against ISIS for more than seven months and have retaken it from the terrorists. This is another breakthrough for the Kurds in the region. They have also recaptured many lost territories and villages around Kobanê, Raqqa, and Manbij. The Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq has set off peshmerga with heavy weapons to Kobanê through Turkey. On 11 October 2015, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF, also Arabic QSD) was announced, a coalition of Kurdish, Sunni Arab and Syriac Christian fighters, led and mostly dominated by the Kurdish militias and supported by US-led alliance. They have successfully expelled ISIS from many key sites. Recently, the Kurds have been invited to Geneva Talk by UN special representative to Syria, Stefan De Mistura. Regarding the future of the Syrian regime and its crisis, time will show the status and goals of the Kurds in the forthcoming years. Recently, there were criticisms against the PYD that they do not let other Kurdish parties operate in Rojava and are disrespectful towards other ethnic and religious groups in the region. Given highly unpredictable occurrences and the changing balance of power, the Kurds will face difficult choices in the future.

About the author

Loqman Radpey received his LL.M from Allameh Tabatabai'i University, Tehran, Iran 2014 while teaching at university from 2008 to 2015 in Sardasht, Mahabad, and Baneh. He is currently a Ph.D. candidate of Public International Law at the faculty of Law and Political Science, University of Tehran. His research interest covers interntional law, human rights, self-determination. His publication includes ‘The Legal Status of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in International Law’ (Journal of Social, Political, and Economic Studies, Winter issue 2014); and ‘The Kurdish Self-Rule Constitution in Syria’ (Chinese Journal of International Law, Oxford University Press, December issue 2015). He has been invited to present his paper at the 14th Annual International Conference on International Studies, 13–16 June 2016, Athens, Greece. Also, he has translated two English books into Farsi.