Why do some middle-income country (MIC) governments use costlier sovereign debt markets when cheaper finance is available from official creditors? This study argues that for left-leaning MIC governments with labor and the poor as core constituents and interventionist economic policy preferences, sovereign debt markets provide an exit option from official lenders that offer cheaper but conditional credit (all else equal). Left-leaning governments finance their budgets this way because, unlike official creditors, market instruments do not include project and program conditions that legally and immediately constrain or adjust policy at the time of borrowing.

This research note makes two contributions. First, it shows that MIC governments' partisan class constituencies inform the sources of credit they prioritize when making annual external borrowing decisions. This adds to work on the politics of public debt structures, including how liquidity affects African government creditor choice (Zeitz Reference Zeitz2021) and why partisanship affects the currency composition of bond issues in both rich and developing contexts (Ballard-Rosa, Mosley, and Wellhausen Reference Ballard-Rosa, Mosley and Wellhausen2021). Secondly, it puts limits on the extent to which sovereign debt markets outside of the rich world discipline borrowers for core political constituencies and economic policy preferences. As investors scrutinize developing countries (Mosley Reference Mosley2003, ch. 4), under many conditions, left-leaning governments are thought to have less access to sovereign debt markets due to their political incentives and economic policy priorities (Brooks, Cunha, and Mosley Reference Brooks, Cunha and Mosley2015, 588–9; Bunte Reference Bunte2019; Campello Reference Campello2015; Gelos, Sahay, and Sandleris Reference Gelos, Sahay and Sandleris2011; Kaplan Reference Kaplan2013; Kaplan and Thomsson Reference Kaplan and Thomsson2017; see also Barta and Johnston Reference Barta and Johnston2018). If investor scrutiny of borrower partisanship drove actual MIC annual borrowings, left-leaning governments with working-class constituents would use sovereign debt markets less than governments implementing policy on behalf of elite constituents. However, this note shows that left-leaning MICs are likely to use more market finance proportional to annual foreign borrowing needs. While this provides policy autonomy in the short run, the cost is more expensive repayment obligations in the future. Partisan politics thus helps explain the structure of external debt in MICs and why some become more exposed to sovereign debt markets than others over time.

MIC borrowing options and implications

MICs are poor enough to access official multilateral or bilateral credit and creditworthy enough to access bond markets and commercial banks. This means MICs should be analyzed separately from low-income countries (LICs) that have little to no market access (IMF 2021, n. 1). This also gives MICs a qualitatively different borrowing menu than rich countries, which cannot regularly access development banks outside of crises. High-, middle-, and low-income country groupings largely coincide with asset manager terminology that delineates between the market access of developed, emerging, and frontier sovereigns.

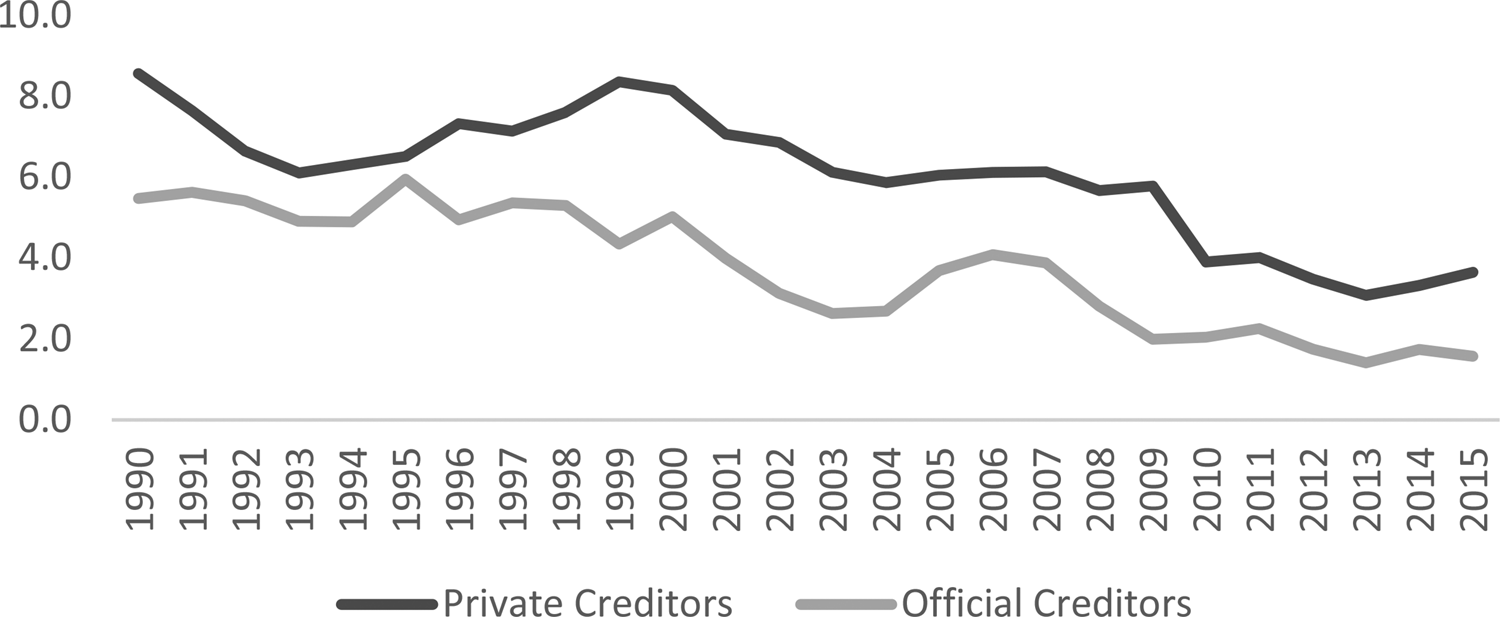

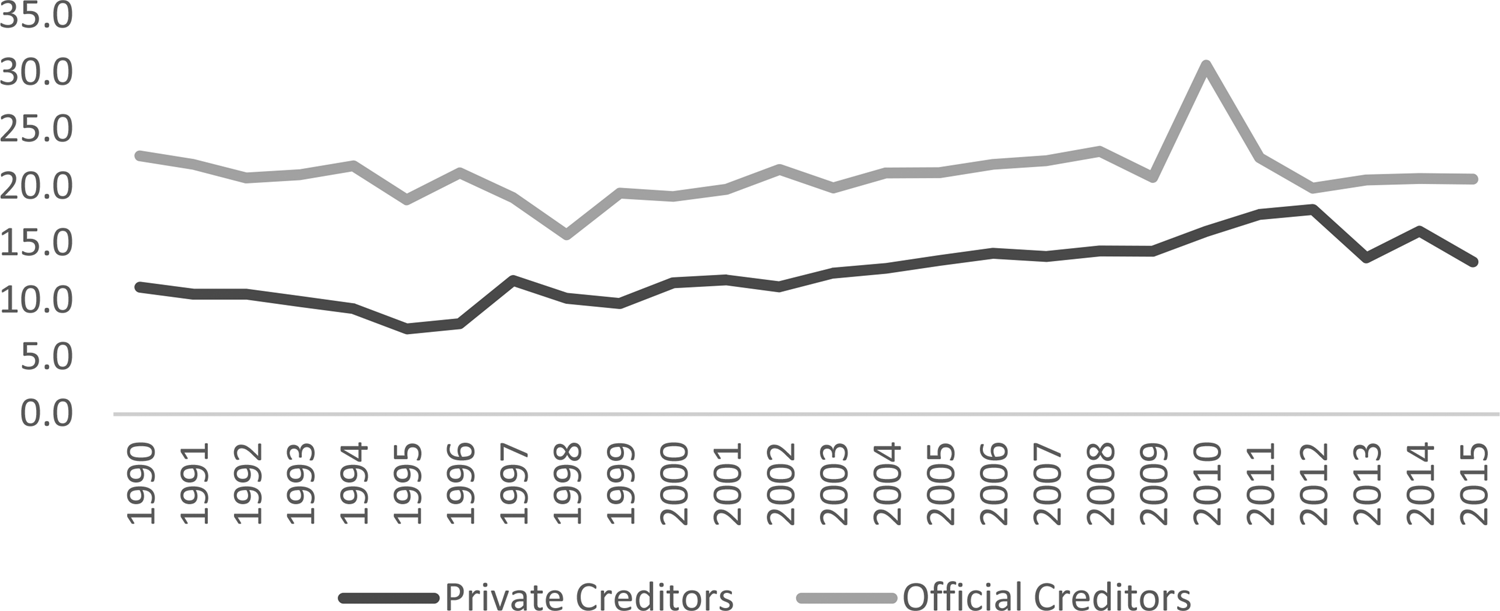

The ability to mix official and market options means MICs face a unique tradeoff when borrowing externally. Official creditors provide price benefits, offering lower interest rates and longer maturities than markets. This is true of major multilaterals (Humphrey Reference Humphrey2014), regional development banks (Humphrey and Michaelowa Reference Humphrey and Michaelowa2013), and Western, Chinese, or other emerging bilateral sources (Morris, Parks, and Gardner Reference Morris, Parks and Gardner2020). Figures 1 and 2 compare the average interest rate and maturity on MIC borrowings from official creditors and markets. Notably, the charts confirm differences between these borrowing options persist through the period of low global interest rates following the 2008 financial crisis. This is intentional. Official creditors tie their interest rates to the London Inter-Bank Offered Rate (LIBOR) to ensure a gap between themselves and market prices persists as global benchmark rates change.

Figure 1. Average interest rate on new external debt in MICs (%).

Source: World Development Indicators and author's calculations.

Figure 2. Average maturity for new external debt in MICs (years).

Source: World Development Indicators and author's calculations.

However, to obtain these price benefits, borrowers must be willing to accept loan conditions. Of course, official lenders’ conditions are not identical. However, they share core traits that distinguish them from bond markets and commercial banks, particularly in the effects they have on domestic groups within a borrower. Project loans from Western and non-Western lenders either adjust what is produced and how it is produced, expose workers to new competition through tied labor or deregulated labor markets, weaken unions, privatize production, or eliminate subsidies (Bunte Reference Bunte2019, 39; Caraway, Rickard, and Anner Reference Caraway, Rickard and Anner2012; Isaksson and Kotsadam Reference Isaksson and Kotsadam2018; Kaplan Reference Kaplan2021, ch. 3; Reinsberg et al. Reference Reinsberg2019). These conditions expose labor and the poor to negative adjustments more than other groups in the borrower. Western lenders also include policy conditions that, though not as dogmatically applied as in the 1990s, continue to expose labor and the poor to the brunt of adjustments that stem from privatization, fiscal consolidation, broad expansion of the tax base, expenditure cuts, and debt reduction conditions (Babb Reference Babb2013; Cormier and Manger Reference Cormier and Manger2021; Kentikelenis, Stubbs, and King Reference Kentikelenis, Stubbs and King2016). Broadly similar conditionalities are why official creditors often co-finance loans.

Identifying that official creditors' conditions make them a different political proposition for a borrower than markets does not mean “market discipline” is never present, nor does it mean markets are politically cost-free in the long term. When highly indebted or around elections, borrowers may interpret investor concerns as conditions and change behavior (Kaplan Reference Kaplan2013; Kaplan and Thomsson Reference Kaplan and Thomsson2017). However, these moments are the exceptions that prove the rule in MIC sovereign debt market access. While investors monitor some macroeconomic indicators in developing countries (Mosley Reference Mosley2003, ch. 4), these mostly shape prices rather than the very availability of finance. This is an important point, as higher prices do not mean a country cannot or will not borrow at those prices (see Beaulieu, Cox, and Saiegh Reference Beaulieu, Cox and Saiegh2012, 710). Moreover, outside of crises, moral hazard and the search for yield ensure markets are often all too willing to lend even when imprudent (Reinhart and Rogoff Reference Reinhart and Rogoff2009). The point is that at the time of borrowing, issuing a bond is a less-scrutinized exercise than negotiating and taking on politically salient and controversial official creditor conditions.

Partisanship, class, and external borrowing preferences

All else equal, then, when are MICs likely to use more expensive market finance? While there is much work on the politics of default (Tomz Reference Tomz2007), there is less on annual borrowing decisions that shape the accumulation of public debt over time. An exception is research on how conservative governments benefit from using official creditors like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (Nelson Reference Nelson2017; Putnam Reference Putnam1988, 457; Vreeland Reference Vreeland2003; Woods Reference Woods2006). This study theorizes that this, in turn, means left-leaning MIC governments resist conditionalities in the name of policy autonomy that allows them to serve working-class constituencies, such as labor and the poor, using sovereign debt markets as an exit option from official creditors when fulfilling annual borrowing needs.

Put differently, markets allow left-leaning governments comparatively “quiet” but expensive borrowing that will not subject core constituencies to adjustment and the government to subsequent political backlash. Indeed, if a left-leaning governing party were to accept conditions that limited its ability to serve core constituents, this would dilute the Left's support for that party, with ramifications for incumbents (Bodea, Bagashka, and Han Reference Bodea, Bagashka and Han2019). For left-leaning parties, the incentive to borrow more from markets than official creditors stems from the need to ensure they have space to implement policies that allow them to serve and maintain their core partisan base (see Lupu Reference Lupu2016). This counters arguments that governments representing labor avoid markets when they borrow (Bunte Reference Bunte2019) and aligns with work on how partisanship affects the currency composition of debt (Ballard-Rosa, Mosley, and Wellhausen Reference Ballard-Rosa, Mosley and Wellhausen2021), while controlling for how global liquidity can also affect the decision to use official or market finance (Zeitz Reference Zeitz2021).

Class-based politics is particularly significant in MICs. As poor countries grow enough to have diverse economies, “the class content of politics also grows, as both capital becomes more powerful and an emerging working class is likely to assert its rights” (Kohli Reference Kohli2004, 416). Moreover, economic integration has only reified the salience of class divides. The disproportionately negative effects that globalization, integrative economic policies, and imposition of them by foreigners have had on lower classes has led developing-country politics to hinge on class cleavages: “[developing-country citizens] mobilize along income/social class lines [because] the globalization shock takes the form mainly of trade, finance, and foreign investment” (Rodrik Reference Rodrik2017, 2). MIC borrowing preferences, then, are likely to be shaped by these class politics.

Labor–capital class distinctions are associated with different economic policy preferences, typically discussed on a left–right spectrum. While this cannot capture the complexities of a policy platform (Rudra and Tobin Reference Rudra and Tobin2017, 296), the class constituents of a party imply important differences in economic policy preferences (Ballard-Rosa, Mosley, and Wellhausen Reference Ballard-Rosa, Mosley and Wellhausen2021; Barta and Johnston Reference Barta and Johnston2018; Beazer and Woo Reference Beazer and Woo2016). Left-leaning parties represent groups dependent on wage labor, unions, government spending, and intervention in various markets for protection from adjustments and promotion of economic equality. When borrowing, then, left-leaning governing parties should resist official lenders' conditions that limit policy autonomy and expose working classes to negative adjustments. In contrast, right-leaning governments are not as likely to resist official creditor conditions that promote integrated production or integrative economic policies. Moreover, capital values debt sustainability, an objective served by avoiding expensive markets and using official creditors' lower interest rates and longer maturities.

In practice, this partisan effect on MIC foreign borrowings occurs by constraining the work of government debt managers, who are technically responsible for negotiating sovereign debt contracts (see Sadeh and Porath Reference Sadeh and Porath2020). However, because partisan ministers must ratify annual borrowing plans, MIC debt managers cannot borrow from official creditors if their conditions would constrain the policies that the governing party is implementing (Cormier Reference Cormier2021). Across regions, there is qualitative evidence that this constraint on MIC foreign borrowings varies by partisanship. Left-leaning governments keep South African public debt managers from using official credit because the “political transaction costs” of conditionality would be too high, while right-leaning governments in neighboring Botswana prefer official creditor policy reinforcement effects and price benefits (Cormier Reference Cormier2021, 1182–5). Thailand's frequent shifts between left-leaning and conservative governments determine when debt managers do and do not use official creditors, as only when conservative parties take office does Thailand have an “interest in official credit” (Interview, Multilateral Official, June 7, 2017). In Peru, while many debt managers “[want] to take even more from [official creditors],” policies of successive left-leaning governments have recently forced more use of bonds (Interview, Domestic Official, November 6, 2017). This leads another official to predict that bonds will continue to constitute a higher proportion of Peru's foreign debt structure, as they suspect left-leaning parties will continue to hold office in the foreseeable future (Interview, Domestic Official, October 31, 2017).

As implied by discussing some of these countries, this theory applies across regime types. Leaders in nondemocracies, one-party democracies, or countries with unprogrammatic party politics must still generate benefits for and cooperation from key constituencies, be they working classes or economic elites (Bueno de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno de Mesquita2005). By extension, borrowing preferences vary across regimes because borrowings must still match the regime's constituents' preferences, as they seek to survive politically (robustness tests confirm dropping certain regimes does not alter findings). This leads to the following hypothesis:

HYPOTHESIS 1 (H1): All else equal, left-leaning MIC governments with labor and the poor as core constituencies use a greater proportion of market-based finance to meet annual foreign borrowing needs.

Empirical tests

A panel of years in which countries were MICs from 1989 to 2016 is used. The Online Appendix lists country-years, descriptive statistics, and variable sources with citations. It also includes discussion of, and tests related to, selection concerns about MIC categorization.

Dependent variable

To model the proportion of borrowing likely to come from markets rather than official creditors each year, the outcome variable is the percentage of new debt that comes from bond markets and commercial banks, rather than official creditors:

Higher values indicate more market use (for data sources, see the Online Appendix). Although the total amount borrowed is the denominator, this does not automatically mean more borrowing leads to a smaller share of market financing. As discussed, MICs typically co-finance from a variety of official sources to meet large financing needs should they prefer to.

Explanatory variable

This study uses two explanatory variables. The first and primary variable captures the relative importance of labor and the poor to a governing party's constituency, using the Varieties of Party Identity and Organization (V-Party) dataset (Lührmann et al. Reference Lührmann2020). On a 0–1 scale ranging from no support to essential support, V-Party's “party support group” variable codes the “core membership and supporters” of a party. We construct a variable accounting for the importance of urban working classes and unions, rural working classes (including peasants), and middle classes (including family farmers) to a governing party's constituency. By averaging the importance of these groups to a governing party in V-Party's coding, we get a variable reflecting the relative importance of labor and the poor to that party (WorkingPoorPrty). For space in this research note, the Online Appendix provides further specifics on constructing this variable. H1 expects that the more important these constituencies are to a governing party, the more the government will use markets to meet its foreign borrowing needs. A robustness test constructs an elite version of this party support variable to confirm such a constituency leads to more official borrowing (that is, the inverse of H1).

The alternative variable is the left–right partisanship of the government, coded using the Database of Political Institutions (DPI) (Beck et al. Reference Beck2001). The DPI codes countries according to the economic policy platform of the governing party, making the dataset a common tool for capturing economic policy preferences and providing an alternative measure for testing H1. Left = 1 if the DPI codes the government as left-leaning and 0 if right-leaning, dropping governments the DPI codes as centrist or unclear to ensure the variable clearly matches the theory's emphasis on the importance of working classes vis-à-vis elites to a governing party. To ensure dropping centrists and the subsequently lower N does not explain the DPI findings, a robustness test uses the variable Center-Left, reasoning that centrists' broader political bases should make their borrowing preferences more similar to left- than right-leaning parties. Results persist.

Controls

Lagged outcome variables control for the degree to which borrowing is simply habitual. Other controls account for supply-side constraints, global market conditions, national economic fundamentals, public debt positions, and political factors. Given space in this research note, please see the Online Appendix for further notes and discussion (including a correlation matrix and discussion of potential post-treatment bias from some covariates).

Market conditions, creditworthiness, and economic fundamentals

USIRates controls for the amount of liquidity available to MICs. Credit Rating is the best rating a country has from Moody's, standard and poor's (S&P), or Fitch that year. A code of 1 means the country is AAA, so higher values should mean less market use. Growth may increase market use, while Inflation and Deficit may lead to less market use. Crisis must also be controlled for since official credit is likely if facing a debt, currency, or banking crisis that year. Debt portfolios are controlled for with Debt Service and Reserves. Debt levels may affect creditworthiness and high reserve levels may alter the perceived tradeoff between official and private options.

Political factors

Democracy, Rule of Law, and Property Rights control for the democratic advantage thesis. PolCycle is the number of years until the next election. The United Nations (UN) voting alignment of the borrower with the United States and with China controls for political alliances with major powers, both of which may lead to more official borrowings.

The data-generating process

Countries make budget and borrowing decisions this year (t) that do not take effect until next year (t + 1). Budget negotiations take place and borrowing strategies are thus designed under the conditions and information known in year t, but borrowings do not become formal until those budgets and funding strategies are implemented in year t + 1. This means the outcome variable and Deficit must be led by one year because they reflect decisions made during year t but not implemented until the budget takes effect in t + 1. PolCycle is also led by one year because, to the extent there is a political business cycle, the budget is made with an eye to what year in the cycle that budget is used. Remaining variables, accounting for conditions and information under which borrowing decisions are made, are included at their year t values. The basic model of MIC foreign borrowing is:

Modeling strategies

A fractional dependent variable requires use of probit and logit models. These nonlinear models do not include unit fixed effects to avoid the incidental parameter problem and instead use errors robust to unit clustering. As this research note uses marginal effects to make inferences, however, linear and generalized method of moments (GMM) models can still be used to recover estimations using unit fixed effects despite the fractional outcome variable (Papke and Wooldridge Reference Papke and Wooldridge2008, 130).

Results

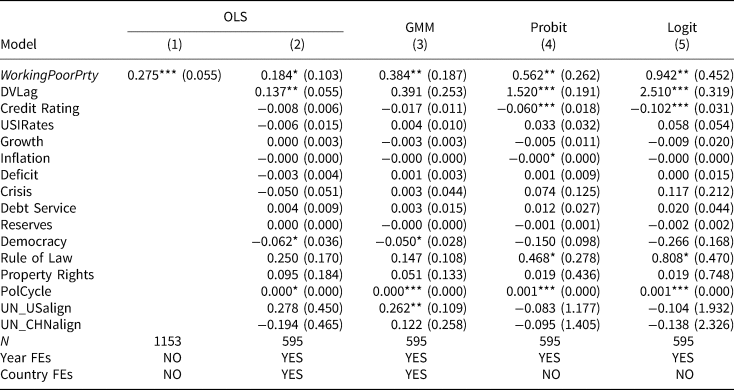

Table 1 reports estimations using the importance of labor and the poor to a governing party's constituency as the explanatory variable. If H1 is correct, the more important these constituencies to a governing party, the more likely the government will be to use a greater proportion of market finance to meet its annual foreign borrowing needs.

Table 1. Modelling the effect of labor and poor constituencies on MIC external borrowing

Notes: Robust standard errors in 1–3; cluster-robust standard errors in 4–5; constants suppressed. Dependent variable, Deficit, and PolCycle led one year (see data-generating process discussion). OLS = Ordinary Least Squares; GMM = Generalized Method of Moments. * p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01.

All Table 1 estimations lend support to H1. Model 1 is a simple ordinary least squares (OLS) correlation. Model 2 is an OLS model with all control variables, unit effects, and year effects. Model 3 is a GMM estimation using collapsed lags as instruments. Model 4 is a fractional probit model, removing unit fixed effects to avoid incidental parameter bias but making errors robust to unit clustering. Model 5 is the same with a logit function.

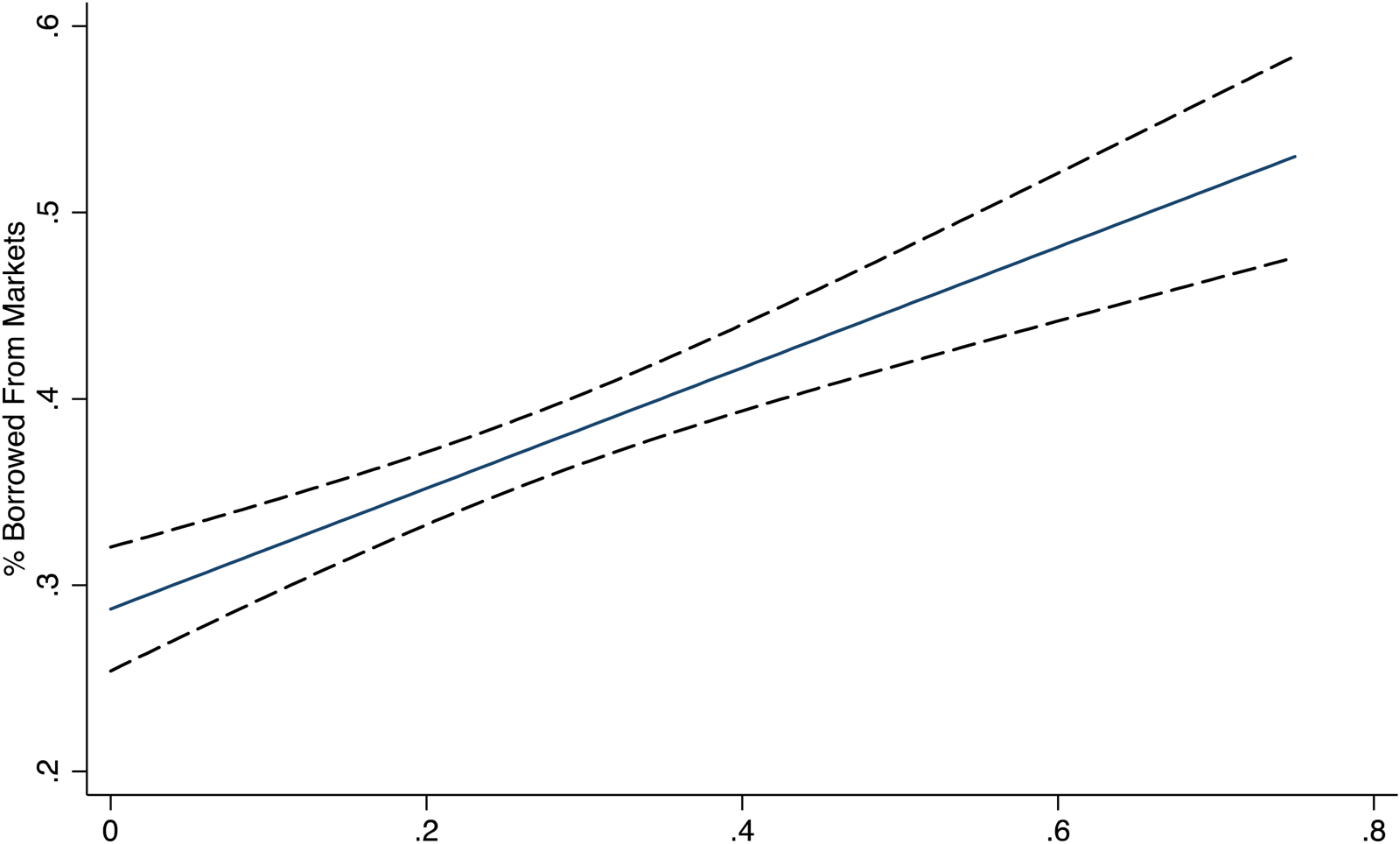

Figure 3 then plots the predicted marginal effects on the proportion of borrowing likely to come from markets rather than official creditors across values of WorkingPoorPrty. As is clear, the greater the importance of labor and the poor to a governing party, the greater the proportion of that government's annual borrowings that are likely to come from market rather than official sources. This is evidence in favor of H1, explained by such constituencies incentivizing the government to use markets to avoid conditionalities, despite higher costs.

Figure 3. Predicted marginal effect of working-class and poor constituencies on MIC market use.

Notes: Strength of working classes and poor in governing party's constituency (WorkingPoorPrty) Model 5 in Table 1 with robust errors clustered on country; 95 per cent confidence intervals.

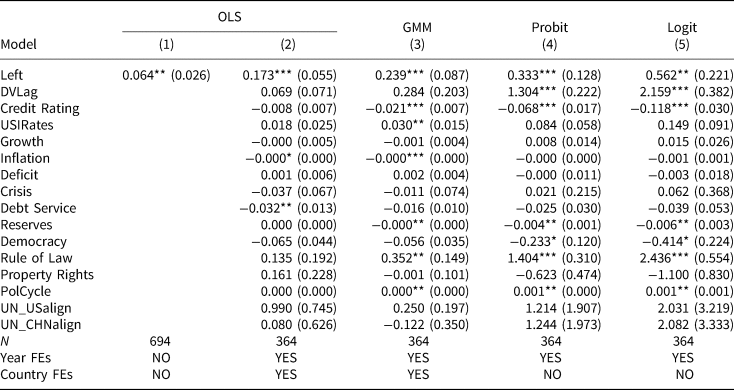

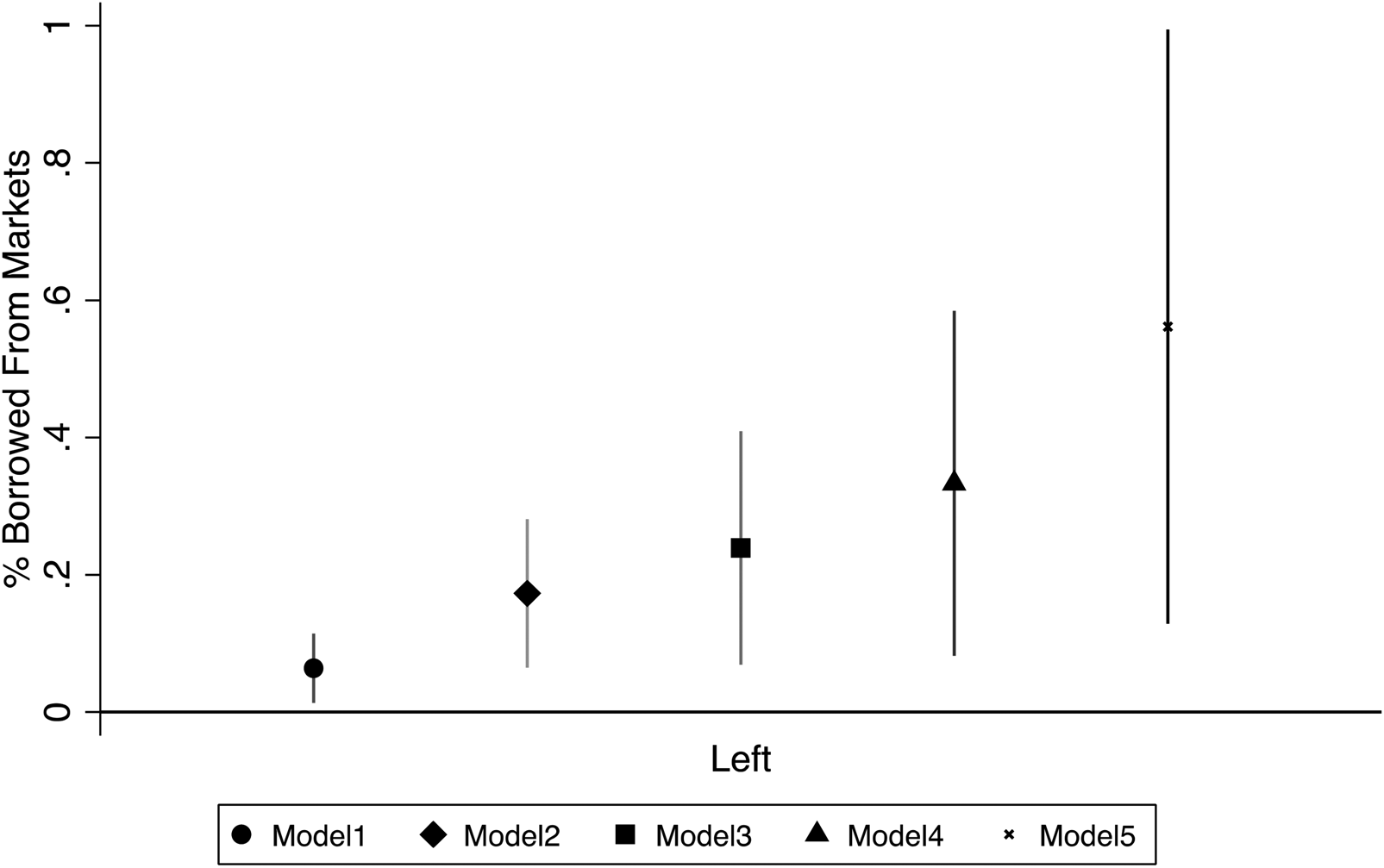

Table 2 reports the same series of estimations using the alternative Left variable. All models estimate that a greater proportion of left-leaning government borrowings come from market rather than official sources. Figure 4 confirms that across these models, the average marginal effect of being a left-leaning party is to use a greater proportion of market finance when borrowing externally.

Table 2. Modelling the left-leaning partisan effect on MIC external borrowing

Notes: Robust standard errors in 1–3; cluster-robust standard errors in 4–5; constants suppressed. Dependent variable, Deficit, and PolCycle led one year (see data-generating process discussion). OLS = Ordinary Least Squares; GMM = Generalized Method of Moments. * p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01.

Figure 4. Average marginal effect of left-leaning partisanship on MIC market use.

Notes: Other covariates held to means; 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Robustness checks

The Online Appendix presents and discusses robustness tests with a variety of alternative specifications, alternative variables, and sample subsets. These include: using elite party support variables rather than working-class variables to test the inverse of H1; dropping countries about to graduate to high-income, so potentially selecting into MIC status; dropping international development association (IDA) recipients; adding centrists; dropping crisis countries; and dropping nondemocracies.

Conclusion

This research note finds class-based partisan politics help explain how MIC governments, with their unique foreign borrowing menu, borrow externally each year. Left-leaning governments with labor and the poor as core constituencies meet annual foreign borrowing needs by using proportionally more market-based finance than other governments. An important implication is that MIC use of sovereign debt markets is not systematically limited according to, or disciplined by, a borrowing government's partisanship and economic policy preferences. This puts into question the often-stylized relationship between national economic policy and sovereign debt market access as MICs accumulate external debt over time. Moreover, it highlights how and why prices do not necessarily determine borrowing choices, an important distinction for future work in the international political economy (IPE) of sovereign debt. Most broadly, the study signals the degree to which MIC governments have enough autonomy when borrowing that domestic politics affects the evolution of external public debt structures in these countries at least as much as supply-side or structural considerations.

Supplementary Material

Online appendices are available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000697

Data Availability Statement

Replication data for this article can be found at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/I4NZXM

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Vincent Arel-Bundock, Leonardo Baccini, Jonas Bunte, Antoinette Handley, Mark Manger, Layna Mosley, Lou Pauly, and Stefan Renckens for discussions and advice, especially in the early stages.

Financial support

None.

Competing interests

None.