Economic history was once a deeply interdisciplinary field. The Economic History Association (EHA) was founded by members of both the American Historical Association and the American Economic Association, and the early volumes of the Journal of Economic History included numerous contributions by historians. But over time, as historians' interest gravitated toward cultural topics, and as the Cliometrics Revolution led to the incorporation of quantitative methods and economic theory into the field, economic history came to be dominated by economists.Footnote 1 Today, the Journal of Economic History and the Association's annual conference include few contributions from scholars trained in history departments. Research in economic history has flourished nonetheless, and the growing accessibility of historical sources such as census microdata, coupled with technological advances such as those related to geospatial information systems (GIS), continue to support rapid advances in the field. Important questions that would have been unimaginably difficult to address in a convincing way just two decades ago are being answered conclusively. Yet for all its methodological sophistication, some of the work by economic historians would have benefitted from the insights and criticisms of scholars trained in history departments, and the absence of many historians from the field has limited its intellectual diversity and the depth of its analysis.

The past decade has seen a resurgence of interest in economic history among historians. Whether the product of waning interest in other topics or a desire to understand the historical forces behind the recent financial crisis and Great Recession, many young historians have chosen to focus on economic history in their work. Particularly among Americanists, this shift is gathering momentum, and works on economic history have been among the most celebrated books produced by historians in recent years. Yet this new wave of research has not brought historians back to the academic field of economic history. The scholars producing it do not think of themselves as participants in the field and have worked in isolation from it. Instead, many of them have styled themselves “historians of capitalism.” A separate community of economic historians seems to be emerging.

In this article I present a survey of ten prominent books by the new historians of capitalism that focus on a variety of topics including finance, slavery, and conservative economic doctrines. My aims are to critically assess their contributions and to point out books that may be of interest to economic historians. I also highlight insights from the work of economic historians that would have strengthened the analysis of historians of capitalism and what their books bring to our understanding of the past. Finally, I suggest some research questions that might create opportunities for cross-pollination, if not collaboration, between economic historians and historians of capitalism. My hope is that this article will begin a much-needed conversation between the two communities of scholars.

The boundaries of the field of the history of capitalism are not well defined, and it is sometimes unclear whether historians working on economic topics intend their work to be part of it. The name “history of capitalism” could be interpreted to embrace any work of historical analysis that is focused on capitalist economies, and an early overview of the field by one its foremost practitioners, Sven Beckert of Harvard University, defined it in this way (Beckert Reference Beckert, Eric and McGirr2011). Yet this definition is so broad that it includes most of the fields of labor, political, social, and business history, as well as economic history.Footnote 2 And in spite of the popularity of the new brand, some historians working on economic history topics do not wish to adopt it and prefer to identify with other fields such as business history. The history of capitalism is not simply work on economic history topics by scholars trained in history departments. It is work with a particular perspective, and it is this perspective that I believe defines the field and distinguishes it from economic history or business history.

This is the significance of the name: rather than adopting the approach of the field of economic history, which seeks to analyze historical economic behavior, historians of capitalism aspire to something closer to social criticism. They focus on the human costs associated with historical economic change; an “activist impulse” seems to animate their work (Rosenthal Reference Rosenthal2016). The “history of capitalism” would seem to denote a research agenda focused on writing the history of capitalism, but this does not characterize the new literature well. Most of the scholars producing it are in fact Americanists, and many are focused on the twentieth century. With few exceptions, the literature is not concerned with the early origins or deep institutional foundations of capitalism, and it does not seek to analyze the full evolution of capitalism over time. None of the books even defines what is meant by capitalism. But then again, capitalism itself is not actually the subject of their analysis. Instead, these works present a critical analysis of economic development in the context of capitalist institutions. The name “history of capitalism” calls attention to the presence of capitalism, but it should mainly be seen as signifying critical social analysis by historians.

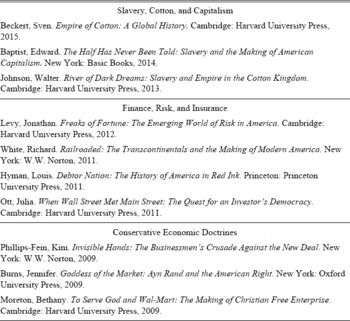

The ten books discussed in this article are listed in Table 1 in the order in which they appear in this essay. I selected the books with input from historians of capitalism and from consultations of reading lists of courses in the field.Footnote 3 Each is well-regarded, and several have won one or more major prizes. Although not a comprehensive list, the ten books are quite representative of the field. I have grouped them into three broad topics: slavery, cotton, and capitalism; finance, risk, and insurance; and conservative economic doctrines.

Table 1 WORKS DISCUSSED IN THIS ESSAY

Source: Author compilation.

Together the books present a critical account of the development of the American economy. There is America's original sin, slavery, and the forcible expropriation of native peoples. There is an ever-growing financial sector, crony capitalism, and struggles over the allocation of newly created risks. And, in the twentieth century, there is a backlash against the New Deal and the welfare state, and the rise of economic doctrines and political ideologies friendly to business interests.

To understand the perspective of historians of capitalism, one has to recognize two sources of influence that figure prominently in much of their work. The first is Karl Polanyi's The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (1944). Although Polanyi himself was an economic historian and an occasional contributor to the Journal of Economic History, his work is not influential among economic historians today. Written partly in response to the work of the Austrian School economist Ludwig von Mises, The Great Transformation makes several arguments that are clearly reflected in the work of historians of capitalism. Polanyi's analysis proceeds from the insight that market economies can be understood only by considering their “embeddedness” within their social and political contexts, which may in fact be hostile to market forces. As we will see, many of the historians of capitalism have focused their analysis on those political and social contexts, rather than on markets themselves.

Polanyi presents an account of the Industrial Revolution and the emergence of national markets and capitalism in Britain. He argues that these developments were made possible only by a series of interventions by the state to dismantle feudal institutions and protect manufacturers through tariffs and other subsidies. This insight enabled Polanyi to point out a fallacy in arguments against government “interventions” in markets made by his contemporaries on the right, such as von Mises: they presume that markets are natural institutions, whereas “there was nothing natural about laissez-faire; free markets could never have come into being merely by allowing things to take their course…laissez-faire was enforced by the state” (pp. 249, 139). Although most of the historians of capitalism are not focused on the early emergence of capitalism, they are deeply concerned with interactions between the state and markets, and they share Polanyi's perspective that the state plays a constitutive role.

Polanyi also argued that unfettered markets are inherently unstable and pose great “perils to society,” which made the transition to capitalism a “double movement.” One movement was aimed at the establishment of capitalism itself, but the other was a “countermovement” aimed at social protection, which used various forms of legislation and “restrictive associations” to mitigate the impact of capitalist development (pp. 71, 132). Polanyi's arguments about the ravages to society of unfettered markets resonate within all of the books of historians of capitalism.

The second major influence is the recent financial crisis and Great Recession. The sudden shock to the financial system, and the many economic sequelae that followed, stimulated broad interest in economic history. Although many of the books discussed in this essay were already in preparation when the crisis occurred, the context in which they were written likely colored the authors' perspectives. Several emphasize the darker side of capitalism and its propensity for crises, and this contributes to their distinctive point of view.

At their best, the books discussed in this essay offer provocative insights and present vivid descriptions of historical contexts drawn from archival sources. Much of the research of economic historians focuses on questions originating in economic theory, which tend to be quite narrow. In contrast, these books present expansive narratives and explore questions that may not be amenable to the analytical tools of economists. The authors' critical perspectives also distinguish their work from that of economic historians and make it relevant to the concerns of many popular readers. The historians of capitalism rightly remind us that economic growth and development can have human costs not captured in average incomes; that our economic history includes no small measure of cruelty, coercion, and expropriation, rather than free exchanges occurring in the context of secure property rights; and that the economic system we have today is not a natural condition, but the outcome of policy choices that could have been made differently.

Yet their critical perspectives sometimes distract their focus away from rigorous historical analysis. Too frequently, the historians of capitalism present arguments without examining the validity of their assumptions or exploring alternative explanations of their implications. None of the books makes any attempt to falsify major elements of their arguments. In some cases, the authors seem to have arrived at insights that are consistent with evidence obtained from some historical sources without analyzing them any further or investigating other sources. The many specious arguments and failures of analytical reasoning in these books undermine their effectiveness as social criticism.

In their zeal to highlight the consequences of capitalist development, the historians of capitalism tend to exaggerate the degree of change that has occurred over time. The analytical frameworks of many of these books draw a sharp distinction between a “modern” or “capitalist” or “developed” period and what came before. In arguing for the unprecedented nature of the developments they observe, the authors sometimes assume that the period prior to their study was fundamentally different. Yet often the phenomena presented as new have clear historical antecedents, and a careful investigation of the connections between periods would have enriched the analysis significantly.

The influence of the recent crisis and Great Recession in these works also creates something of a pitfall for their analysis. Just as poor historical analogies can distort our understanding of the present, modern analogies can produce fallacious or unsound historical analysis if misapplied. Although financial development often leads to volatility, and although venality and corruption among financiers seems to be as close to a historical constant as one can find, not all finance is harmful. The financial sector performs a vitally important function, but the very nature of that function makes it vulnerable to manipulation, fraud, and instability. The growth of the financial sector over the long run has been made possible by institutional developments—some imposed as regulations, some developed within the financial sector itself—which have sought to bring these problems under control. The books by the historians of capitalism include scarcely any analysis of these institutional developments.

A closely related problem is that the authors have failed to engage with the economic history literature. Economic historians have produced sophisticated analyses of the issues of interest to historians of capitalism, even if they have approached them with a different set of tools. Ignoring the economic history literature has led historians of capitalism to make assertions that have been refuted conclusively and to get important elements of their arguments wrong. In some cases, they have unwittingly revived debates that were resolved long ago. Later in this essay, I describe some analytical techniques and insights from the field of economic history that I believe would strengthen the work of historians of capitalism. But before describing those insights, I first comment on each of the ten books individually.

DISCUSSION OF THE BOOKS

Books on Slavery, Cotton and Capitalism

Among the most prominent works of historians of capitalism are three books on cotton production under slavery. Perhaps not surprisingly given their topic, these books present the bleakest vision of American history, as they emphasize the vast cruelty and coercion in nineteenth-century economic life. Slavery has also been one of the most important topics in the field of economic history, and among all the books of the historians of capitalism, these would have benefitted the most from greater engagement with the economic history literature.Footnote 4

The most ambitious is Sven Beckert's Empire of Cotton: A Global History. The book presents an international account of the causes and consequences of the Industrial Revolution, but it does so by focusing exclusively on cotton.Footnote 5 Its great strength is its account of the spread of the Industrial Revolution into different regions of the world, as it follows the adoption of new textile machinery. Beckert's account of this process is consistent with the ideas of Polanyi in that he emphasizes that the role of the state in “[f]orging markets, protecting domestic industry, creating tools to raise revenues, policing borders, and fostering changes that allowed for the mobilization of wage workers” (p. 155) was crucial for industrialization.

Beckert argues that the colonial empires of the European powers, with their heavy reliance on the violent expropriation of indigenous peoples and on slavery, constituted an early phase of capitalism, which he denotes “war capitalism.” One of his main arguments is that the Industrial Revolution and the “industrial capitalism” it spawned were made possible by war capitalism. Thus, Beckert presents a theory of the Industrial Revolution that emphasizes its origins in “slavery, colonial domination, militarized trade, and land expropriations” (p. 60).

Any theory of the Industrial Revolution needs to address the question: Why did it begin when and where it did? Why 1780s Britain and not Amsterdam, or for that matter Song China? Beckert identifies a number of different mechanisms by which war capitalism enabled industrial capitalism to develop in Britain in the 1780s. Like Eric Williams in Capitalism and Slavery (Reference Williams1944), Beckert argues that the fortunes made in the slave trade and on sugar plantations in the Caribbean created a source of finance for the innovations in cotton textile production at the center of the Industrial Revolution.Footnote 6 But he also argues that the trading networks within the colonial empire were critically important: the British merchants of the 1780s were uniquely positioned to exploit the vast global market for cotton textiles, since they “dominated the transoceanic trade in cottons, and they had firsthand knowledge of the fabulous potential wealth that could come from selling cloth” (p. 64). War capitalism therefore created a demand-driven inducement to expand textile production, and it also helped provide the wherewithal on the supply side to develop new technologies to serve that demand.

Research by economic historians casts doubt on some of these arguments and lends support to others. David Eltis and Stanley Engerman (Reference Eltis and Engerman2000) concluded that relative to other British industries at the time of the Industrial Revolution, the total value added and growth-inducing linkages of the British slave trade and Caribbean slave plantations were not particularly large.Footnote 7 On the other hand, Beckert's emphasis on the role of trade in the growth of the Industrial Revolution is quite consistent with the theoretical model of Ronald Findlay and Kevin O'Rourke (Reference Findlay and O'Rourke2007). But more importantly, the vast literature on the Industrial Revolution that economic historians have produced shows that it originated in the creation and adoption of a wide range of technologies, such as the steam engine and coke blast furnace, which were not directly connected to textile trading networks. Indeed, the steam engine appears rather awkwardly out of nowhere in Beckert's cotton-focused account, whereas its emergence is coherently explained by research that emphasizes British labor and energy costs, or the scientific advances associated with the Enlightenment.Footnote 8

Although some of the new technologies of the Industrial Revolution may not have been closely linked to war capitalism, the slave plantations of the Western hemisphere certainly did provide an elastic supply of raw cotton to European manufacturers, which fed the textile industry's expansion. Like Kenneth Pomerantz's The Great Divergence, Beckert's book emphasizes the importance of colonial land holdings in enabling the British economy to expand beyond its ecological limits.Footnote 9 Initially, sugar plantations in the Caribbean and South America converted some of their lands into cotton production. The industry's rapidly growing demand for cotton then fueled what Beckert characterizes as war capitalism within the United States, as the native peoples of the South were violently driven into other regions and cotton production using slave labor spread into those territories. Beckert then argues that rapid productivity growth in cotton production during the first half of the nineteenth century was due in part to a “systematic intensification of exploitation” of American slaves (p. 115).Footnote 10

The role of cotton slavery in America's economic development is the focus of Edward Baptist's The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism. This book seeks to challenge the perception that slavery was somehow separate from the rest of the economy, arguing instead that slavery was crucial to the development of American capitalism. But it also seeks to tell the story of cotton slavery in a way that focuses on the lived experiences of the enslaved people and the cruelties they endured.

Drawing on the narratives of escaped slaves and the papers of slave owners, Baptist presents a detailed portrait of many elements of the southern economy. Considerable attention is devoted to the internal slave trade and the movement of slaves into the Mississippi River delta region, but there is also much detail on plantation life, finance and banking, religious practice, and political debates over the expansion of slave territory, among many other topics. There is a particularly engaging account of musical and social rituals on plantations, which Baptist uses to argue that enslaved African-Americans were the “true modernists, the real geniuses” of their time (p. 163). Baptist also plays with the language used by slave owners to characterize themselves and their slaves in an effort to explore different dimensions of slaveholders' power. Some of these passages are insightful, some less so.Footnote 11

The focus of The Half Has Never Been Told is not cultural but economic, and much of its economic analysis is so flawed that it undermines the credibility of the book. For example, Baptist makes the astonishing claim that all of the increase in productivity in cotton picking observed in the antebellum era was due to increases in the whipping and torturing of slaves. This claim enables him to make the central argument of the book, that the “ultimate cause” of the Industrial Revolution was the “systematized torture” of American slaves (pp. 135, 141; see also p. 413). Notwithstanding the fact that the Industrial Revolution began before American slaves were producing cotton in any significant quantities, Baptist's claim regarding torture and productivity is false, and the evidence he offers in support of it consists of a selective account of the quantitative and narrative record.Footnote 12 Baptist relies on quantitative evidence produced by economic historians Alan Olmstead and Paul Rhode (Reference Olmstead and Rhode2008a). Yet Olmstead and Rhode (p. 26–31) show that the increase in productivity they observe was due primarily to biological innovations—the introduction of new cotton varieties that were more productive and easier to pick—and rule out any substantial changes resulting from plantation management or greater intensification of slave effort.

Baptist also offers a calculation of the contributions of cotton slavery to American gross domestic product (GDP) in 1836, from which he concludes that “almost half” of economic activity in that year “derived directly or indirectly” from slave-produced cotton (pp. 321–22). This is a disastrously mishandled undertaking, full of obvious manipulations that overstate cotton's contribution.Footnote 13 And yet Baptist's focus on GDP causes him to miss one of cotton's most important contributions to American economic development: the foreign currency revenues it produced, which increased specie reserves in the banking system.

As has been said of other polemical but problematic works, The Half Has Never Been Told is perhaps best understood as “history as rhetoric” rather than “history as scholarship.”Footnote 14 To impress upon modern readers the brutality that enslaved African-Americans endured in vivid and affecting language is an important contribution that historians are uniquely positioned to make. But Baptist's account contains the very same kind of overstatements as those who have sought to minimize the viciousness of slavery have made. The importance of slavery in American economic development and the cruelties that enslaved people were subjected to need no exaggeration.

Like The Half that Has Never Been Told, Walter Johnson's River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom describes economic life in the antebellum Mississippi River delta in detail. But to a much greater extent than Baptist's book, River of Dark Dreams is, at its core, an ethnography of the Cotton South: the analysis focuses on cultural interpretations of economic behavior. The book vividly describes many spectacles—slaves working at night by torchlight; the feeding of enslaved children like livestock in a common trough; the improvised trials of slaves accused of capital crimes—and offers provocative interpretations of their cultural meanings. Many of the book's arguments seek to challenge the work of other historians, for example, by pointing out the analytical limitations created by their emphasis on slaves' “agency” (p. 217), or their characterizations of the writings of advocates for slavery as “dehumanizing” (p. 207).

Yet there is also economic analysis in the book, and it often falters. One major problem is Johnson's repeated claim that “planting and productivity were measured by a calculation of bales per hand per acre” (p. 177; also pp. 13, 153, 197, 217, and 254), which as Gavin Wright (Reference Wright2014, p. 878) notes “makes neither mathematical nor economic sense.” It is telling that this mischaracterization of productivity measurement ultimately makes little difference for the book's argument. Johnson is concerned only with the general implications of slaves' position as inputs into production for their well-being, and does not engage with the specific details of plantation management techniques or input ratios. Virtually any measure of productivity, no matter how erroneous, would serve his purpose.

More importantly, Johnson ascribes enormous significance to attempts to conquer Cuba and Nicaragua by private armies of pro-slavery “filibusters,” and to the push in some southern states to re-open American ports to the slave trade. Arguing that it is anachronistic to limit our conception of “the South” to the American states that seceded from the Union, Johnson claims that it is important to consider “where Southerners (and slaveholders in particular) thought they were going,” and take their “imperial aspirations” seriously (pp. 14–16). It is fascinating to read Johnson's accounts of the filibusters' military campaigns, many of which descended into slapstick and farce. Here Johnson uses the correspondence and promotional literature that these filibusters produced, which read like transcriptions of white supremacists' fever dreams, to analyze the ideologies of slave society in interesting ways.

But historians have been right to marginalize these movements. Slaveholders, who had configured the political institutions of southern states to ensure their dominance, would have suffered substantial capital losses if the importation of slaves were permitted, and had nothing to gain from access to land in places like Nicaragua. Wright (Reference Wright1978, p. 150), in fact, uses the efforts to re-open the slave trade as a “test case” for his analysis of the importance of slave values in southern politics. He finds its rejection by southern politicians to be entirely consistent with efforts to protect the value of slavery.

These three books serve as an interesting counterpoint to the economic history literature on slavery. Whereas the economic history literature sought to investigate the sources of productivity in slave agriculture, the historians of capitalism emphasized the suffering that accompanied productivity gains—from the violent expropriation of native peoples, to the forced migrations and sales of enslaved people, to the brutality that slaves endured.Footnote 15 Yet each of these books would have been more compelling and better works of history if they had engaged with the economic history literature more fully.

The lack of engagement with the work of economic historians leads these authors to make assertions that have been conclusively refuted. Each of these books argues that slavery depended on the acquisition of new territory for its survival or at least for its economic vitality.Footnote 16 Yet the amount of unexploited land suitable for the cultivation of cotton within the slave states at the time of the outbreak of the Civil War was immense.Footnote 17 There is also a revival of the notion that plantations grew only cotton and were dependent on imports from other regions for food.Footnote 18 This view, which figured prominently in Douglass North (Reference North1961), was based on a misinterpretation of trade statistics that did not account for the fact that agricultural products shipped to New Orleans were re-exported to other destinations at high rates, as shown by Albert Fishlow (Reference Fishlow1964) and Robert Gallman (Reference Gallman1970). There are discussions of productivity gains in cotton production that minimize the role of the introduction of new cotton varieties, which are now known to be among the primary drivers of those gains.Footnote 19 Among the most labor intensive phases of cotton production is the harvest; biological innovations that produced taller plants and bolls that were easier to pick significantly increased slave-labor productivity. Indeed, the narrow focus on cotton in these works prevents them from assessing the full significance of slavery in the development of the American economy. Although cotton was certainly the most valuable slave crop, large numbers of slaves in Kentucky, Missouri, and Virginia were employed in the production of crops that are traditionally associated with small family farms, such as wheat (Wright Reference Wright2006).

More importantly, the lack of engagement with economic historians limited the analytical perspectives of each of these books. Most seem aware of Robert Fogel and Stanley Engerman's Time on the Cross (1974), and some repeat its arguments about the profitability of slavery or the efficiency of slave plantations.Footnote 20 But they do not seem to have taken seriously the debates among economic historians that followed the publication of that book (e.g., David and Temin Reference David and Peter1974, Reference David and Peter1979). Some of that literature has challenged Fogel and Engerman's claims regarding scale economies in plantation agriculture and the role of gang labor.Footnote 21 But the literature that developed in the wake of Time on the Cross analyzed slavery in new ways.

Wright (Reference Wright2006) argued that the literature up to that point had overemphasized slavery as a form of work organization, and instead argued that it is best understood as a system of property rights, which had important implications for economic development. Real-estate property owners typically have a strong incentive to support urbanization or the provision of public goods because the benefits will be capitalized in land values. In contrast, slave owners have no such incentive: their property is moveable, and its value is not affected by local economic development. Slave owners, therefore, had “little to gain from improvements in roads,” and “no particular desire to attract settlers by building schools and villages and factories” (Wright Reference Wright1986, p. 18). They also had weaker incentives to produce labor-saving innovations. Only after emancipation did patent rates for mechanical devices for cotton harvesting and processing approach those associated with corn or wheat.Footnote 22 Baptist (Reference Baptist2014, p. 128) notes that cotton picking was not mechanized until the twentieth century and characterizes this as an obstacle slaveholders overcame, rather than an effect of slavery itself.

Books on Finance, Risk, and Insurance

A separate strand of the history of capitalism literature has focused on finance and the closely related topics of risk and insurance. This marks a significant departure for the field of history, which until relatively recently has not focused on finance.

Among the most creative work by the historians of capitalism is Jonathan Levy's Freaks of Fortune: The Emerging World of Capitalism and Risk in America. Levy's is an account of the evolution of economic risks and their distribution, over the nineteenth century. At the center of the argument is the belief that Americans developed a “vision of freedom that linked the liberal ideal of self-ownership to the personal assumption of ‘risk’” (p. 5). Levy focuses on the ideas, legal doctrines, and market innovations that determined the allocation of new risks as they emerged. Over the course of the book's eclectic narrative, the reader is presented with discussions of whether an insurrection on a slave ship absolved insurers of liability; whether fraternal societies that offered life insurance to their members competed with life insurance corporations; the use of mortgage securitizations in the 1880s; the emergence of futures trading and debates about its legitimacy; and the strategies by financiers to control competitive pressures and manage market risks by merging competing firms together, which they actually characterized as a form of “socialism.” As Levy notes, it is only in the twentieth century that the public sector became an important absorber and manager of risks, but the book's narrative does not extend into that period.

Among the books reviewed in this essay, Levy's reflects the influence of Karl Polanyi most strongly and even makes frequent use of Polanyian terms such as “double movements” and “countermovements.” In a sense, Freaks of Fortune can be thought of as a re-telling of elements of The Great Transformation for the United States, with a focus on private efforts to contain risk. This leads to some fascinating insights, but it also creates problems for the analysis. Levy ignores changes in the “economic chance-world” that did not originate in capitalism itself and therefore excludes some of the greatest sources of “freaks of fortune” in American history, such as the Pennsylvania oil rush and the California gold rush. But more importantly, the analogy between the experiences of Britain and the United States is imprecise. Capitalism arose in Britain through a long dismantlement of feudal institutions that fundamentally changed society. Few of those institutions existed in colonial North America, and the rise of capitalism there may have been somewhat less transformative. Much of Levy's argument proceeds from the unexamined assumptions that the changes that occurred over the nineteenth century were fundamental in nature, rather than merely an acceleration of processes that had already existed, and that economic fortunes became much more volatile over time.Footnote 23

For example, Levy claims that the growth of mortgage markets and institutions meant that by the early 1890s, “the logic of American farming had been utterly transformed. The farmer's distinctive hedge—his land—was lost…Their land could no longer shield them from the markets' vicissitudes” (pp. 151–52). The claim is that farmers could only obtain land and equipment through mortgages, and a mortgaged farm was risky and required the operators to produce cash crops rather than food for consumption. Yet it seems doubtful that there was ever an era in which American farmers focused purely on subsistence.Footnote 24 The practice of agriculture generally entails a need for credit, and American land titles were uniquely friendly to the commodification of land.Footnote 25 Levy also notes that the development of mortgage markets tended to lower mortgage interest rates (p. 153), which would seem to pull the rug out from under his own argument.

Economic historians will find this book fascinating and frustrating. The allocation of risks, such as those related to retirement, health, or individual economic fortunes, is an issue of paramount importance. Levy explores some unusual and often-neglected elements of its history. However, there are some confused statements about finance and financial markets that are difficult to overlook. Levy makes the claim that “antebellum America was relatively poor in finance capital. Much of the nation's wealth was in the physical capital of land and slaves” (p. 78). This is specious reasoning: when someone bought land or slaves, they paid the seller, whose holdings of “finance capital” increased by exactly as much as the buyer's decreased, so that the total amount of national “finance capital” was not affected.Footnote 26 There is a discussion of futures trading that barely notes its effects on commodities markets.Footnote 27 Instead, he focuses on the fanciful legal reasoning that some jurists resorted to in order to distinguish futures trades from bucket-shop wagers or other forms of gambling. And some of the most important mechanisms by which Americans sought to manage and limit risks, namely imposing regulations on banks (or in some cases, banning banks), are conspicuously absent from the story.

Risk also plays a role in what is sometimes referred to as “crony capitalism,” in which well-connected figures in the business world use their political influence to get the state to underwrite their ventures. Crony capitalism figures prominently in Richard White's Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America. Drawing on the correspondence and business records of the industry's leading figures, this important book details the mismanagement, corruption, deceit, and fraud that were ubiquitous among the early transcontinentals, whose construction was heavily subsidized by the state. Beyond the losses borne by the federal government and by investors in defaulted securities, White chronicles other impacts and concludes that “in terms of their politics, finances, labor relations, and environmental consequences, the transcontinentals were not only failures but near-disasters” (p. 507).

The book is huge and does indeed explore issues such as labor relations, rate setting practices and the impact of the transcontinentals on the settlement and environmental exploitation of the West. But its great strength is its analysis of the financial manipulations of railroad insiders and its detailed descriptions of scandals such as Crédit Mobilier, which reflect an enormous amount of archival research. It colorfully chronicles how figures like Henry Villard became “superheroes of bad management—powerful, daring, able to destroy railroads at a single blow” (p. 217)—in contrast to works such as Alfred Chandler (Reference Chandler1977), which have emphasized the managerial successes of the railroad industry. Particularly fascinating are the descriptions of the tactics employed by rival operators to strike at each other by manipulating the legislative process, and the betrayals and deceptions within groups of promotors of the same railroads. This book will be a valuable resource for anyone interested in a clear account of the problems of railroad finance in the nineteenth century.

Yet, like Freaks of Fortune, this book will frustrate the economic historians who read it. White documents a number of episodes of deception—insider trading schemes, accounting fraud so extreme that executives had little idea of their own railroads' financial condition, the sale of bonds of completely bankrupt railroads that were represented as being perfectly sound—that resulted in substantial losses. Given the amount of money that was subsequently raised by the industry, this is unlikely to have been the whole story. Insiders with privileged access to information can swindle investors. But in response to deception, rational investors will adapt their behavior by refusing to invest, or by investing only in securities in which they are protected from fraud—perhaps by purchasing only senior mortgage bonds. White does not explore the consequences of the fraud and deception for the railroads' interactions with financial markets, nor does he present any clear information on the composition of outstanding railroad securities and how it may have evolved over time.

This is where analogies to the recent crisis may have led White astray. He views the bankers underwriting these securities as generally complicit in the fraud or unwilling to do anything about it (pp. 375, 380, et seq.). But the all-important reputations of the major securities underwriters of the late nineteenth century would have been severely harmed by repeatedly marketing fraudulent securities. It is worth remembering that there were no ratings agencies at the time—investors had to rely on the representations made by bankers when securities were sold. In response to fraud, the bankers who underwrote railroad securities did indeed make changes. They began to take active roles in railroad governance where they could to police the behavior of railroad insiders (Carosso Reference Carosso1970; Hilt Reference Hilt2014). It is noteworthy that White discusses the failure of the Northern Pacific in the Panic of 1893, but he does not mention the subsequent highly successful reorganization of the railroad by James J. Hill and J.P. Morgan, which led to two Morgan partners joining its board (see Campbell Reference Campbell1938).

The two remaining books on the subject of finance and risk focus on the development of financial markets during the twentieth century. Both are focused on the social and political contexts within which the development of financial markets was embedded, to use the Polanyian term. Louis Hyman's Debtor Nation: The History of America in Red Ink analyzes the development of American consumer credit markets over the twentieth century. And Julia Ott's When Wall Street Met Main Street: The Quest for an Investor's Democracy chronicles the emergence of mass participation in securities markets in the early twentieth century.

Debtor Nation begins around 1920 with innovations such as the enactment of small loan laws and the emergence of finance companies. The book then follows legal and institutional developments in consumer credit over subsequent decades, such as the changes made to mortgage markets by the New Deal, restraints on consumer credit introduced during WWII, and the evolution of postwar credit markets and the rise of credit cards and securitization. Hyman's treatment of these and other issues is thorough, and emphasizes the role of public policy in shaping the growth of credit markets. Among all the works discussed in this essay, Hyman's is the only one that presents substantial quantitative evidence in support of its arguments. The book is a valuable resource on twentieth century credit market development.

Readers interested in the institutional foundations of modern mortgage markets will find Hyman's chapter on the subject particularly useful. He presents a succinct account of the Housing Act of 1968, which privatized the Federal National Mortgage Association and created the modern mortgage-backed security. And he follows subsequent innovations in mortgage markets—often initiated by the government in partnership with the financial sector—into the 1980s and 1990s, which created the collateralized mortgage obligation (CMO), and which led to similar innovations in the financing of credit card receivables.

Hyman's book makes a valuable contribution but it has two important shortcomings. First, it is framed as a study of the “modern credit system,” but this is based on an exaggerated distinction between the “modern” period and the apparently pre-modern one. Hyman argues that prior to the 1920s, when his study begins, personal debt was “confined to the margins of the economy,” and that the changes documented in the book created “a new role” for personal debt “within American capitalism” (p. 1). Although the credit market institutions that served ordinary households in the nineteenth century were organized differently, they functioned in similar ways, and more importantly, excluding them from the analysis causes Hyman to miss some potentially important insights. For example, beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, households seeking credit for home purchases could turn to a growing number of building and loan associations (Bodfish Reference Bodfish1931). And in the 1880s, western mortgages were securitized as part of “debentures” or “covered bonds” and marketed to eastern investors. Both of these institutional structures collapsed in financial crises.Footnote 28 Including them in the study could have added historical insight to the discussion of the instability of later credit-market institutions.

The second shortcoming of Hyman's book is its treatment of the recent financial crisis. Its narrative does not extend into the early 2000s, a reasonable choice for a history book. It therefore does not document the changes in mortgage market institutions, such as the enormous growth in subprime mortgage lending, which occurred immediately prior to the crisis. Yet the book concludes with an analysis of the crisis, in which many of its proximate causes are either absent or given only superficial mention. That analysis also includes some failures of economic reasoning. The securitization of consumer loans, for example, is characterized as a “diversion of capital into nonproductive investments” (p. 286). So long as there is no fraud such lending helps facilitate valuable economic activity; the same reasoning would imply that the entire financial sector is unproductive.

In When Wall Street Met Main Street, Julia Ott argues that the increase in securities ownership among ordinary households in the 1920s was not the inevitable outcome of industrialization or financial development. Instead, it was the product of deliberate efforts on the part of both policy makers and leaders from the financial sector and industry to promote the ownership of financial assets. In this interesting account, households were induced to become investors as part of a social and political agenda that followed from theories of “proprietary democracy.”

Like many scholars before her (e.g., Mitchell Reference Mitchell2007), Ott ascribes enormous significance to the liberty loan campaigns of WWI. These were conducted not only to raise funds to finance the war effort, but also to elicit participation by virtually every element of society, from women's clubs to religious organizations, in the promotion of the bonds in a series of highly publicized “bond drives.” Ott argues that business leaders learned from the example of the liberty loans, and in response to their own political concerns, such as those relating to labor relations or the imposition of new regulations, held their own campaigns to market their securities to their employees and to other households. In accordance with theories of a New Proprietorship, business leaders sought to give ordinary households a stake in their success, and the New York Stock Exchange even styled itself “the people's market.”

Like Debtor Nation, Ott's book presents the developments of the early twentieth century as historically unprecedented, and in doing so, exaggerates the distinctions between that period and earlier ones. Ott argues that prior to 1900 “most Americans believed that bond- or stockholders warranted little consideration in economic theory or policy” (p. 2). In fact, corporations and the rights of their shareholders and creditors were among the most important concerns of nineteenth century Americans, and highly charged rhetoric about them is nearly ubiquitous in that era's political discourse (see Lamoreaux Reference Lamoreaux, Collins and Margo2015a). One can even find early antecedents of some of the precepts of the New Proprietorship within early nineteenth century doctrines of corporate regulation (see Hilt Reference Hilt2008, Reference Hilt2013). Excluding any discussion of the earlier history forecloses any possibility of understating the historical foundations of the developments at the center of the book.

Books on Conservative Economic Doctrines of the Late Twentieth Century

There is a long tradition in the field of history of studying the social movements of the left. In contrast, Alan Brinkley (Reference Brinkley1994, p. 409) described American conservatism as “something of an orphan in historical scholarship,” despite its importance for understanding the twentieth century. Since then, interest in conservatism has grown among historians. Some of this new work has been produced as part of the field of the history of capitalism, which has shown growing interest in conservatism and conservative economic doctrines. Economic historians, on the other hand, have shown relatively little interest in the study of the history of economic ideas and doctrines. There is, of course, a small subfield of economics devoted to the history of economic thought, and some of its practitioners have produced studies of conservative intellectuals (e.g., Goodwin Reference Goodwin2014). But in general, the research on conservative economic doctrines by historians of capitalism represents a unique contribution with no parallel in the field of economic history. Although these books are quite different from the others reviewed in this essay, in a sense they are the most complementary to the work of economic historians. They do not analyze the content of the ideas they study or editorialize about them, but instead focus on the individuals and organizations devoted to promoting them.

Kim Phillips-Fein's Invisible Hands: The Businessmen's Crusade Against the New Deal chronicles the efforts of business executives beginning in the 1930s to promote economic ideas critical of the welfare state. The book includes carefully researched accounts of the origins of think tanks and other organizations that were funded by business beginning in the 1950s, which “helped to form the infrastructure for the rise of the conservative movement” (p. 86). Among these were Friedrich von Hayek's Mont Pelerin Society, the organization that became the American Enterprise Institute, and a few others that never grew beyond obscurity. The book highlights the role of a handful of particularly influential figures, such as Lemuel Boulware of General Electric, and follows the growing efforts of businessmen to promote conservative economic ideas up through the 1970s. Its detailed narrative presents a clear account of the rise of conservative economic doctrines and their connection to anticommunism and to conservative religious thought. The book concludes with the election of Ronald Reagan, a former General Electric spokesperson, to the presidency.

This thoroughly-researched book raises a number of interesting questions. Why did some businesses and executives support the New Deal (and related policy changes), whereas others recoiled? And why did some conservative organizations become quite influential and successful, whereas others failed in obscurity? Phillips-Fein does offer some insight into the latter, in her suggestion that some “had the misfortune to spin their theories at a time when the economy was stable and growing,” whereas the think tanks of the 1970s “worked in an era when liberalism seemed no longer able to deliver on its promises” (p. 167). But exploring questions such as these was not her aim.

Ayn Rand, who is discussed in Phillips-Fein's book, is the focus of Jennifer Burns' Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right. Born Alisa Rosenbaum in Russia in 1905, Ayn Rand led a fascinating life, and Burns' book, written with access to Rand's papers, is enormously enjoyable to read. Best described as an intellectual biography of Rand, Goddess of the Market details the development of her philosophy, which came to be known as objectivism, and the influences that produced it. At the outset, Burns notes the “nearly universal consensus among literary critics that [Rand] is a bad writer” (p. 2), but Burns' book is free of such condemnations of Rand's ideas.

Goddess of the Market complements Invisible Hands, as it details Rand's interactions with some of the same individuals and institutions and explores their intellectual agreements and disagreements. One of the most interesting insights of the book is that Rand had little patience for academic economists, even those who would have been her natural allies. She regarded von Hayek as “pure poison” (p. 104), and characterized Milton Friedman and George Stigler’s 1946 pamphlet on rent control, Roofs or Ceilings, as “pernicious” (p. 117), due to their sympathies for some limited role for intervention by the state. Burns notes that Rand's objectivism “left no room for elaboration, extension, or interpretation” (p. 6). It is possible that her influence has grown after her death, in part, because her absence has enabled her ideas to evolve somewhat in the hands of others. But the analysis of the book makes clear why Rand has remained influential and “part of the underground curriculum of American adolescence” (p. 282).

Wal-Mart is one of the most prominent corporate supporters of the organizations discussed in Invisible Hands and is known for its conservative workplace culture. Bethany Moreton's To Serve God and Wal-Mart: The Making of Christian Free Enterprise presents a history of that culture. Moreton's book describes the early efforts of the firm to establish its appeal among conservative rural communities by adopting cultural values consistent with theirs. Its workforce was divided along gender lines, with women working as sales clerks, and men in managerial positions. Moreton argues that this enabled Wal-Mart to appeal to local customers and to gain access to an inexpensive source of labor, married women. Drawing heavily on internal publications such as Wal-Mart World, Moreton chronicles the early growth and development of the firm.

Although Moreton's book offers some interesting insights, it also illustrates the limitations of a purely cultural approach to the analysis of a business. She ascribes enormous significance to Wal-Mart's efforts to assimilate the values of the Ozarks, the region where the firm originated. But she fails to make any attempt to evaluate the importance of these values relative to other major elements of the firm's business model, such as its procurement policies or pricing strategies. More importantly, Wal-Mart quickly grew well beyond the Ozarks to become the world's largest private employer. Its workforce now rivals that of the People's Liberation Army of China in size.Footnote 29 The book does not explore the ways in which Wal-Mart's efforts to appeal to rural evangelicals in Arkansas and Missouri shaped its growth in places like Mexico. Did it replicate its labor practices from the Ozarks there, or did it need to adapt them? Too many such questions arise when reading this book.

INSIGHTS FROM ECONOMIC HISTORY: INSTITUTIONS AND COUNTERFACTUALS

The field of history has its own strengths, which are different from those of economics. I am not suggesting that historians of capitalism should adopt the methods of economic historians. Yet historians of capitalism would benefit from assimilating into their own thinking some of the analytical constructs and techniques developed by economic historians. The most conspicuous of these are institutional analysis and counterfactuals. It is worth noting that these are among the contributions for which the two Nobel laureates for economic history, Douglass North and Robert Fogel, were best known.

By institutions, economists mean the “humanly devised constraints that structure political, economic, and social interaction,” which encompasses the formal, as in laws or constitutions, and the informal, as in customs or traditions (North Reference North1991, p. 7). To be sure, all of the books by historians of capitalism discussed here are concerned with institutions—slavery, evangelical Protestantism, or proprietorship—and with cultural concepts that are closely related to institutions.Footnote 30 The Polanyian concept of “embeddedness,” so influential among historians of capitalism, naturally points towards incorporating institutions into the analysis. Yet with the exception of Beckert (Reference Beckert2015), these books lack any analysis of the role institutions play in shaping or constraining economic development over time. Incorporating this latter form of institutional analysis into the research agenda of historians of capitalism would have enabled them to produce works of greater insight.Footnote 31

Consider the institution of slavery. In a series of influential works, Engerman and Kenneth Sokoloff (Reference Engerman and Sokoloff2000, Reference Engerman and Sokoloff2005, Reference Engerman and Sokoloff2012) have argued that slavery has been associated both with high levels of inequality and with institutions designed to perpetuate that inequality. Focusing on comparisons among former colonies in the Western Hemisphere, they note that slave societies tend to limit access to the franchise, create poorer educational systems, restrict immigration and access to land, and, in general, tend to offer low levels of economic opportunity for ordinary people. The books on slavery discussed here observe the lack of industrialization, urbanization, and economic mobility in the cotton south. But they fail to appreciate the implications of these characteristics for economic development. The preoccupation Beckert, Baptist, and Johnson have with demonstrating the productivity of slave agriculture and the compatibility of slavery with capitalism causes them to overlook the harmful effects of slavery on institutions and development.Footnote 32 Slavery is compatible with capitalism in general but incompatible with what Majewski (Reference Majewski2015) calls Schumpeterian or dynamic capitalism and the institutions needed to support it.

Slavery in the American South had more far-reaching implications than the brutal exploitation of African-Americans. As the Engerman-Sokoloff analysis predicts, the institutions of southern states were configured to serve the interests of slaveholders and did not offer much opportunity for non-slaveholders. Although these institutions have evolved over time, they remain quite different than those of other states. Through its effects on institutions, slavery has had a variety of malign effects on the American South that continue to be felt. Slavery was certainly profitable and created a number of large fortunes, but its legacy has made whole regions of the United States poorer today than they would otherwise have been.

In contrast to the impulse to show dramatic change over time, a focus on institutions might highlight sources of intertemporal continuity in the analysis of historians of capitalism. Levy's Freaks of Fortune, Hyman's Debtor Nation, and Ott's When Wall Street Met Main Street all describe economic developments that they characterize as new. But these changes were shaped at least in part by long-established institutions, such as legal doctrines governing relationships between debtors and creditors (see Coleman Reference Coleman1974). An investigation of the extent to which such institutions influenced the economic changes at the heart of those books would have both deepened the analysis and made claims about dramatic change more credible.

The historians of capitalism would also have benefitted from incorporating counterfactuals into their analysis. These are, of course, thought experiments in which some condition is changed, contrary to fact, and the consequences considered. Many historians apparently have a strong distaste for counterfactual histories (see, e.g., Evans Reference Evans2013 and Tucker Reference Tucker1999). Yet the reason economic historians think about counterfactuals is not due to an interest in specifying alternative histories.Footnote 33 Rather, it is because all statements about causal relationships contain counterfactuals. To say that the gold standard caused the Great Depression is to say that absent the gold standard, the Great Depression would not have happened; these two statements are equivalent. There is of course no way to know exactly what the international monetary system of the late 1920s would have looked like in the absence of the gold standard without making strong assumptions, but thinking about that world helps identify forces unrelated to the gold standard that may have contributed to the Great Depression. Economic historians typically investigate counterfactuals not by specifying counterfactual histories, but by comparing cases where a condition is present to cases where it is absent.Footnote 34

The books by historians of capitalism all make causal statements, which contain implicit counterfactuals. But few of them are expressed in clear terms, and none is evaluated in depth. Carefully analyzing these counterfactuals may have led to different, or perhaps more nuanced, conclusions. To give one example, the books on slavery argue, in slightly different ways, that American slavery was necessary for the Industrial Revolution.Footnote 35 This sounds reasonable: American slave plantations became the most significant producers of raw cotton for the British market, and raw cotton was a necessary input for the British textile producers who were the vanguard of the Industrial Revolution. But analyzing the counterfactual embodied in that statement may have revealed it to be incorrect.

Let us assume that American raw cotton was actually necessary for the Industrial Revolution. The question then is whether slavery was essential for the production of that cotton, or stated in counterfactual terms, whether in the absence of American slavery, the raw cotton necessary for the Industrial Revolution could have been produced. The production of American cotton was indeed dominated by slave plantations, and the small yeoman farmers of the South were often engaged in subsistence farming. But the inference that slave agriculture was necessary for large-scale cotton production in the American South, or that smallholders could not be viable producers of cotton there, is unwarranted. Research by David Weiman (Reference Weiman1985) has shown that following the Civil War and emancipation, the expansion of transportation infrastructure and the growth of commercial centers in the Upcountry region of Georgia enabled the small yeoman farmers to reorient their production away from subsistence and toward cotton. The political and economic institutions of slavery likely constrained the development of railroads and market infrastructure in the Upcountry and effectively blocked many smallholders from the market access that would have enabled them to become viable cotton producers.Footnote 36 Once slavery was gone and problems associated with market access were resolved, the yeomen of the Upcountry became major cotton producers.

The soil and climate in parts of the American South make it among the most productive areas in the world for growing cotton. It is not unreasonable to expect that smallholders without slaves could have produced large cotton crops. Absent large slave owners, the region would have been settled in different ways, perhaps resembling what unfolded in parts of the American West. The quantity of cotton produced may not have increased as rapidly, but American cotton farms would still have helped serve the demand of British producers.Footnote 37 American slavery was not actually necessary for the Industrial Revolution. These authors may not have intended to claim that in the absence of slavery the Industrial Revolution would not have happened. But this is a clear implication of an argument that slavery was “crucial” (Baptist Reference Baptist2014, p. 141) to the Industrial Revolution.

Johnson's River of Dark Dreams contains a rejection of such counterfactual analysis, stating that “[h]owever else industrial capitalism might have developed in the absence of slave-produced cotton and Southern capital markets, it did not develop that way” (p. 254). Richard White's Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America answers this point beautifully: “Considering only what happened is ahistorical, because the past once contained larger possibilities, and part of the historian's job is to make those possibilities visible; otherwise all that is left for historians to do is explain the inevitability of the present” (p. 517). Anyone wishing to argue for the centrality of slavery in capitalist development needs to consider what could have been possible without slavery, and a world without American slavery but with the Industrial Revolution was indeed possible. Historians of capitalism wish to highlight the tragedy of American slavery by claiming it was essential for industrialization. I would argue that it is more tragic that slavery may not actually have been necessary.

Some of the other authors, such as White (Reference White2011), do state explicit counterfactuals. However, there is often little elaboration or critical analysis of evidence.Footnote 38 In When Main Street Met Wall Street, Ott states that theories of the New Proprietorship “provided the stock market with a legitimizing ideology. Without it, the advent of broad-based, direct investment in corporate stock in the 1920s could not have occurred” (p. 131). Ott should be commended for making this clear counterfactual statement of her argument. But beyond an assertion that the liberty bond drives of WWI and some related policy changes alone were insufficient to lead to ordinary households owning stock, she offers no evidence in support of her argument. Yet further analysis of this assertion suggests that it may be false. The “roaring twenties” witnessed a speculative mania, particularly beginning in 1927. It is not unreasonable to imagine that with extremely high returns on the stock market, even in the absence of the New Proprietorship many American households would have chosen to invest in the stock market. Ott's focus on the social and political contexts within which the market developed, rather than on the market itself, leads her to neglect these factors in her analysis.

More broadly, thinking about counterfactuals may constitute a useful way for historians of capitalism to refine their ideas, or potentially identify new ones. For example, Phillips-Fein's Invisible Hands and Burns' Goddess of the Market both follow the evolution of conservative economic doctrines and efforts to promote them. The books are intellectual histories, but lurking within them are counterfactuals about the impact of those ideas and the think tanks behind them. What if the American Enterprise Institute and other such organizations had never been created, or Ayn Rand had never lived? How much impact did they actually have? Did they cause changes to occur, or did they merely create the ideological foundations for movements that would have occurred anyway? Such questions are fundamentally important, and are ideal areas for future investigation by historians of capitalism.

ECONOMIC HISTORY AND THE HISTORY OF CAPITALISM: THE PROSPECTS FOR DIALOGUE

I have argued that the analysis of historians of capitalism would be improved by the assimilation of analytical techniques and insights from economic history. But it is also the case that economic historians' understanding of the concepts and contexts that they study would be deepened by engagement with the work of historians of capitalism. Economic historians might also find ideas and conjectures in the work of historians of capitalism that they could pursue further using the methodological approach of economics. Each field would be strengthened by insights and criticisms that would come from serious engagement with the other. Any level of engagement—even if it constitutes little more than scholarly critiques and debates—would be worth pursuing.

One opportunity for engagement might be for historians to take up some of the fundamental questions related to institutions that economists have been unable to answer. In recent years, economists and economic historians have produced a wave of empirical research on the modern impact of historical institutions.Footnote 39 Yet little is known about the specific mechanisms by which particular institutions influence economic development over time or the factors that may cause institutions themselves to evolve. Some progress has been made on these questions using the tools of game theory (e.g., Greif and Laitin Reference Greif and Laitin2004), but historians might be uniquely positioned to shed light by focusing on the origin or evolution of particular institutions, or on the specific effects of institutions over time in particular historical contexts. In a sense, a great deal of the analysis by historians is related to such questions, but the insights from their work have not yet been connected to the literature on institutions. Historians might also be inspired to critique some of the claims made by economists regarding the origins or effects of particular institutions, which would help improve that literature.

The success of the books reviewed here demonstrates the value of highlighting the role of capitalism in historical analysis. Another opportunity for greater interaction between the two communities of scholars might be for economic historians to join historians of capitalism in focusing explicitly on capitalism in their research. Economic historians have analyzed economic interactions in many different contexts, generally without addressing whether those contexts conform to a definition of capitalism.Footnote 40 The two-volume worldwide history of capitalism edited by Larry Neal and Jeffrey Williamson (Reference Neal, Neal and Williamson2014) represents a first step toward focusing on capitalism in the work of economic historians. Any response to that work from historians of capitalism may represent a starting point for dialogue.

The closely related question of the origins of capitalism in North America may represent another opportunity for interaction. The effects of capitalism itself might be clarified if pre-capitalist or non-capitalist contexts can be identified and compared to conditions under capitalism. Given the obvious value of such analysis for understanding capitalism, it is somewhat surprising that historians of capitalism have not already begun to pursue it. Of course there is a literature on the Market Revolution of the early nineteenth century (e.g., Sellers Reference Sellers1992) and an older literature on whether or not the colonial economy constituted a “moral economy” or was always market-oriented.Footnote 41 But much of the evidence on which the participants in that debate have relied is fragmentary, and the mechanisms by which capitalism came to North America may not be completely understood. Questions such as these may be of interest both to historians of capitalism and economic historians, and the pursuit of such questions may lead to greater interaction between them.

Conclusion

The emergence of the new history of capitalism marks a return to research on economic history by scholars trained in history departments. Their work is, however, quite distinct from the field of economic history, which is both a strength and a weakness. On the one hand, it proceeds from a different perspective, emphasizing social criticism. On the other hand, its neglect of insights from economic history often weakens its analysis and undermines its credibility as social criticism.

The popularity of the books by historians of capitalism also suggests some lessons for economic historians. The books are engaging and interesting to read, and they address concerns of popular readers. Perhaps too much of the work of economic historians is written purely for academic economists, even when it holds important insights that are relevant to much broader audiences. Economic historians need to do more to engage with popular readers and to make their work accessible. The public face of economic history should not be limited to historians of capitalism.