Introduction

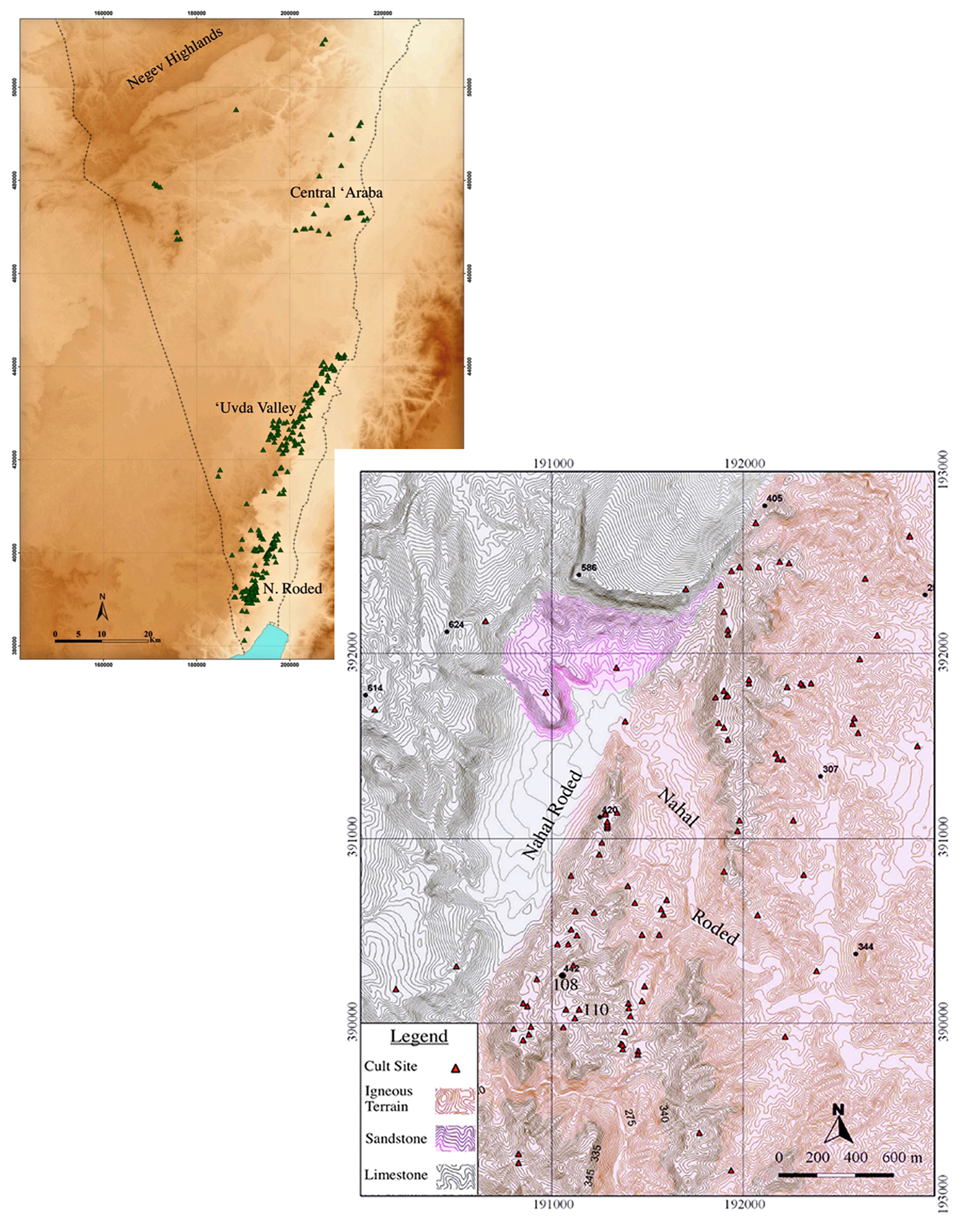

In the southern Negev, approximately 370 mountain cult localities (called ‘Rodedian’ sites) are known (Figure 1). Most are attributed to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB, eighth to sixth millennia BC) and contain unique features and artefacts, such as low, stone-built installations and cells, standing stones, perforated stones and stone bowls (Figure 2; Avner et al. Reference Avner, Shem-Tov, Enmar, Ragolski, Shem-Tov and Barzilai2014). One such cult site, Naḥal Roded 110, situated around 6km to the north-west of the city of Eilat, was excavated to assess its chronology, material culture, organic remains and spatial layout, and to elucidate site function and palaeoclimate.

Figure 1. Left) distribution of ‘Rodedian’ sites in the southern Negev; right) location of Naḥal Roded 110 and adjacent sites.

Figure 2. Salient features of Rodedian sites: 1) perforated standing stone (fallen); 2) anthropomorphic image (found fallen); 3) ‘vulva-shaped’ stone (photographs by U. Avner).

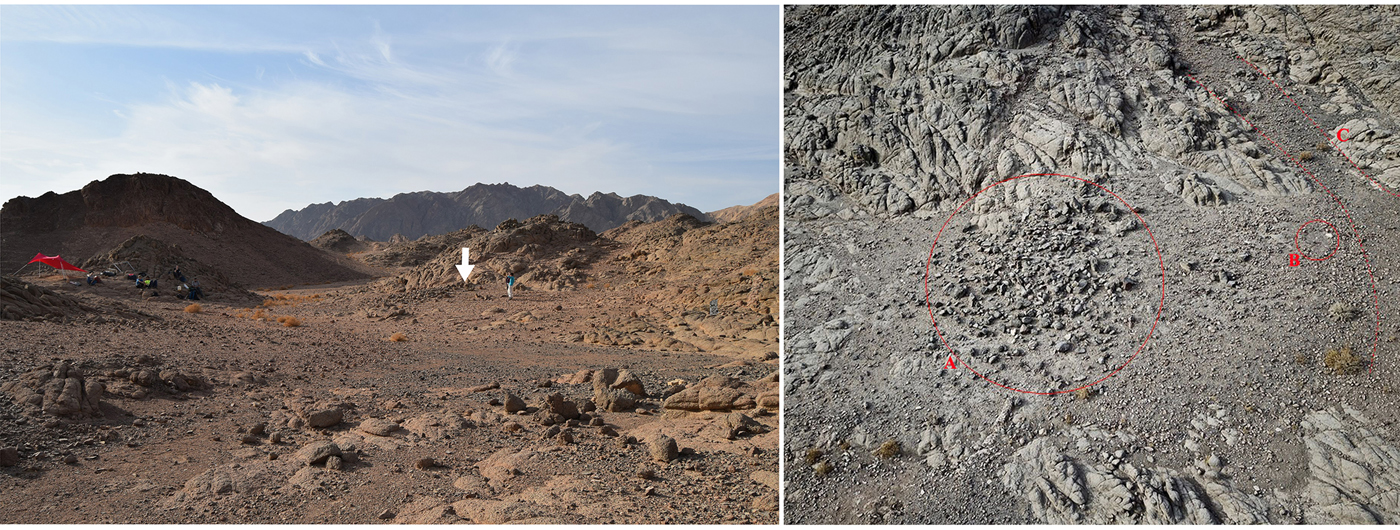

The site covers an area of approximately 150m2 and lies at an elevation of 420m asl within a small, igneous rock embayment. First surveyed in 2004, flint and stone objects were found on the surface, and a collapsed structure and hearth identified (Figure 3; Avner et al. Reference Avner, Shem-Tov, Enmar, Ragolski, Shem-Tov and Barzilai2014).

Figure 3. Left) arrow shows site location within the embayment, facing north-west; right) aerial shot of the site before excavation, showing the collapsed structure (A), suspected hearth (B) and run-off channel that cuts it (C) (photographs by U. Avner).

Excavation

In December 2017, a 1m2 grid was laid out, covering all surveyed features. All surface finds were collected and plotted by square. Three test trenches were opened, traversing both the structure and hearth (Figure 4). Excavation revealed that the deposits are deeper than first assumed, occurring in pockets within the bedrock. The ash-like deposit associated with the hearth is around 5m in diameter (Figure 4) and contains large quantities of lithics, faunal remains and charcoal, as well as several built features—probably small hearths. The excavation ended at a depth of 0.2m without reaching bedrock or the bottom of the ash. Excavation of the collapsed structure was limited. It is also around 5 m in diameter and reaches at least 0.5m in depth (Figure 4). The original form is unclear; it may correspond to the round, desert habitations of the PPNB (e.g. Goring-Morris & Gopher Reference Goring-Morris and Gopher1983; Ronen et al. Reference Ronen, Milstein, Lamdan, Vogel, Mienis and Ilani2001), or represent a series of semi-circular walls, similar to ancient desert hunting blinds (e.g. Lönnqvist & Lönnqvist Reference Lönnqvist and Lönnqvist2011).

Figure 4. The site during excavation, showing the three test trenches (dashed); note the wide extent of the ashy deposit.

Dating

Two charcoal samples from the top and two samples from the base of the ash deposit gave average ages of 7000 cal BC and 7200 cal BC respectively, confirming the attribution of the site to the Late PPNB. The range of dates and numerous hearths imply that multiple burning events occurred. Samples for optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating were also taken from the base of the ash and the structure, and are in the process of being analysed.

Finds

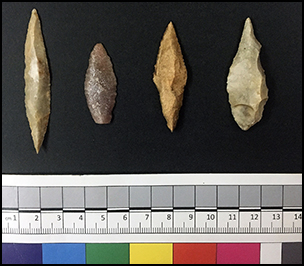

The excavated lithics comprised debitage and a few tools—mainly projectile points (Figure 5) of the Amuq type typical of the Late PPNB (Goring-Morris & Gopher Reference Goring-Morris and Gopher1983). The high frequency of core-trimming elements indicates that intensive knapping was conducted on site, although no flint sources occur on the igneous mountain. Abundant, well-preserved faunal remains were recovered in and next to the ashy deposit. All remains belong to raptors (superfamilies Accipitridae, Falconidae and possibly Strigidae), with the European honey buzzard predominating (Pernis apivorus) (Figure 6). This connects the site to the spring and autumn raptor migrations that still pass over Eilat (e.g. Leshem & Yom-Tov Reference Leshem and Yom-Tov1998). The symbolic association of raptors with death, fertility and rebirth is well established in Neolithic iconography and zooarchaeology (e.g. Peters et al. Reference Peters, von den Driesch, Pollath, Schmidt, Grupe and Peters2005; Marom et al. Reference Marom, Garfinkel and Bar-Oz2017). Preliminary results of pollen retrieved from sediment samples yielded typical Saharo-Arabian taxa (e.g. Tamarisk) with elements of Irano-Turanian steppe vegetation (e.g. Asteraceae).

Figure 5. Typical tools from Naḥal Roded 110, numbered left to right: 1–3) Amuq points; 4) an elongated borer (photograph by M. Birkenfeld).

Figure 6. Humeri of the European honey buzzard (Pernis apivorus) from Naḥal Roded 110 (photograph by L.K. Horwitz).

Conclusions

The excavation at Naḥal Roded 110 has yielded many surprises, including the depth and extent of ashy deposits, evidence for on-site flint knapping, preservation of organic remains and the exclusive representation of birds of prey. All are unique features for such a remote site. We should note that all raw materials—flint for tools, limestone for cultic objects, Red Sea shells and wood for kindling—had to be carried up steep and rugged terrain to the site from the wadi below. Naḥal Roded 110 either served as a seasonal hunting camp with the aim of killing raptors during their migration, with ritual activities associated with this endeavour taking place on site, or functioned as a predominantly ritual locality, with the raptors brought as offerings. Whichever is correct, it is clear that Naḥal Roded 110 contains physical and spiritual elements that are unique, even when compared to coeval desert sites. The discoveries emphasise the enormous potential of further investigations at this and other Neolithic mountain-top sites in the region.

Acknowledgements

Research was funded by the Irene Levi-Sala CARE Archaeological Foundation and the National Geographic Foundation. We thank the volunteers who joined us, Avi Gedalia of the Israel Nature and Parks Authority, and Rahamim Shemtov and Johan Fjellstrom for their logistical assistance.