Introduction

While World Englishes scholarship has always been concerned with different types of English varieties, Expanding Circle (i.e., non-postcolonial) Englishes have had a ‘late start’ in being added to its research remit. As a result, much important work in this area remains to be done. Expanding Circle Englishes in general and Asian Expanding Circle Englishes in particular are still neglected in many handbooks of World Englishes (e.g., in The Cambridge Handbook of World Englishes; Schreier, Hundt & Schneider, Reference Schreier, Hundt and Schneider2020). Notable exceptions here are, for example, The Routledge Handbook of World Englishes (Kirkpatrick, Reference Kirkpatrick2020; including, among others, chapters on Japanese, Chinese, and Slavic Englishes) and The Handbook of Asian Englishes (Bolton, Botha & Kirkpatrick, Reference Bolton, Botha and Kirkpatrick2020; including, among others, chapters on Taiwanese, Cambodian, and Indonesian Englishes). While traditionally much focus has been laid on matters of language policies, education, and attitudes, corpus linguistic approaches to Expanding Circle Englishes have become more and more relevant (see, e.g., Edwards, Reference Edwards2016 for the Netherlands; Rüdiger, Reference Rüdiger2019 for South Korea). In this article, we present the first results from a corpus-based study of Taiwanese English, drawing on the pilot version of a spoken Taiwanese English corpus.

Taiwan is located in East Asia and has been described as ‘an Expanding Circle society with ambitions to move into the Outer Circle’ (Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi, Bolton, Botha and Kirkpatrick2020: 553). In this paper, we will compare our results on Taiwanese English to another East Asian English variety, that is, South Korean English. South Korea constitutes a great point of comparison in this regard as we find a number of similarities between both regional contexts (beyond being located in the same broader geographical region). Both countries, for example, have been described as exhibiting an explicit orientation towards the United States (see Seilhamer, Reference Seilhamer2019: 188 for Taiwan; Grant & Lee, Reference Grant, Lee, Kubota and Lin2009 for South Korea) and have a keen demand for private English education (epitomized in a flourishing business of private English learning institutions, known in Taiwan as buxiban and in South Korea as hagwon). Furthermore, even though learned as an additional language in both contexts, English plays an important role in the form of social, cultural, symbolic, and economic capital in Taiwan and South Korea (see, e.g., Seilhamer, Reference Seilhamer2019: 173 for Taiwan; Park & Abelmann, Reference Park and Abelmann2004; Park Reference Park2011 for South Korea). Last but not least, in both cases, different stakeholders have proposed the adoption of English as an official language (see Chen et al., Reference Chen2018 for Taiwan; Yoo, Reference Yoo2005 for South Korea).Footnote 1

In this paper, we first give the relevant background information on the Taiwanese context, with a particular focus on language education policies. Next we introduce the pilot version of TASE, the Taiwanese Spoken English corpus. Using keyword analysis to compare TASE to the Spoken Korean English corpus (SPOKE), we discuss some first analytical starting points, before investigating two morpho-syntactic patterns, that is, plural marking on the noun and the general use of pronouns, in more detail.

English in Taiwan

The island of Taiwan, with a population of 23.5 million (National Statistics, 2021), is located to the southeast of mainland China across the Taiwan Strait. Kobayashi (Reference Kobayashi, Bolton, Botha and Kirkpatrick2020: 548) points out that Taiwan should be considered a multilingual society, as a number of languages are in use: various Formosan languages, Mandarin, Hokkien, Hakka, and Taiwan Sign Language (see Tai & Tsay, Reference Tai, Tsay, Bakken Jepsen, Clerck, Lutalo–Kiingi and McGregor2015). Due to the dominance of Mandarin Chinese, which is also the de facto official language, Taiwan has, however, been described as a ‘pseudo-monolingual’ society (Go, 2018, quoted in Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi, Bolton, Botha and Kirkpatrick2020: 548). Language education policy in Taiwan, particularly English education, consequently has been shaped by nationalism, modernization and economic growth, as well as globalization (cf. Tsao, Reference Tsao, Baldauf and Kaplan2000). The following sections present a brief description of language education policies in relation to the history, and the political and economic development in Taiwan before turning to a discussion of English education in the last two decades, especially Taiwan planning to implement bilingual education by 2030.

Earlier language education policies in Taiwan: From the 17th century to 2000

Up to the 17th century, there are no written historical records of languages used in Taiwan. In the following 400 years, four major political regimes ruled Taiwan, all of which had an effect on language education; these four regimes include European colonization, the Qing Dynasty, Japanese colonization, and the Kuomintang (KMT) Nationalist government (Wu & Lau, Reference Wu, Lau, Kirkpatrick and Liddicoat2019). European colonization, namely, the Dutch (1624–1662) and the Spanish (1626–1642), had limited impact on language policies in Taiwan. Religion, more specifically, the Dutch's intent to convert the aboriginal people to Christianity, resulted in the creation of Sinkang, a Romanized written form for the language spoken by the aboriginal tribe of Siraya. Second, the Qing government extended its language policy of teaching Chinese as a lingua franca to the aboriginal population and to other residents who spoke local Taiwanese Hokkien or Hakka in their daily life. The Qing governance of Taiwan ended in 1895 after it lost the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), which marked the beginning of a half-century of Japanese colonization. The Japanese regime's ambitious scheme of Japanization of Taiwan became evident in its prohibition of speaking local vernaculars, including Hokkien and Hakka, in all private domains and the teaching of Japanese as the colonizer's language in school. During the Japanese colonization, Japanese with its vocabulary and syntactic structure mixed with some forms of Dutch and aboriginal languages resulted in linguistic hybridity and creativity in Hokkien (Simpson, Reference Simpson and Simpson2007). It is only with the end of the Japanese colonization of Taiwan after the Second World War and the Kuomintang Nationalist government (KMT) regime arriving and ruling Taiwan till 2000 that language education policy, particularly English education, was motivated by ‘status planning’ of Mandarin Chinese (Cooper, Reference Cooper1989) and the driving force to economic prosperity (Chen, S.–C., Reference Chen2006). Before 1987, Mandarin Chinese was privileged as a nationalist language over other local dialects (Tsao, Reference Tsao, Baldauf and Kaplan2000). After the lifting of martial law in 1987, the shift of political power from the KMT to the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in 2000 and the need to open the market internationally resulted in an open-minded attitude toward diversity in using languages. This most prominently affected language education policy in two ways: first, raising people's awareness of speaking local vernaculars for revealing their ‘Taiwanese’ identity; and second, favoring English as a dominant foreign language for promoting globalization (Wu & Lau, Reference Wu, Lau, Kirkpatrick and Liddicoat2019).

Current language education policies in Taiwan: Localization and globalization

After the DPP gained political power, localization or so-called Taiwanization (Wu, Reference Wu2011) reversed language education policy by the implementation of ‘Local-Language-in-Education’ (LLE), which refers to the inclusion of teaching local vernaculars, especially Taiwanese Hokkien, in primary education and reducing the hours of teaching Mandarin Chinese as the national language. According to the Ministry of Education (MOE) 2001 curriculum guidelines, local vernaculars as mother tongues are more than means of daily communication: they are an embodiment of Taiwanese people's cultural identities. In addition to localization, the interplay of economic and political development in tandem with globalization further reshape the language ecology and education landscape of Taiwan, determining English language education. The implementation of English language education in this context is to facilitate the ‘simultaneous promotion of internationalization’ in response to ‘social change and national goals’ (Chen, S.–C., Reference Chen2006: 322).

English Education Policy and the 2030 Bilingual Nation Development Goal

More recently, the English Education policy (EE) has been enforced to embrace globalization, particularly in three aspects: (1) English being introduced as a compulsory subject in primary education in 2001 with two class periods of teaching per week, in most counties starting from Year 3, and in some cities, including the capital, Taipei, starting from Year 1, (2) an English exit requirement for college/university students to pass certain threshold scores before graduation, (3) English as a Medium of Instruction courses being promoted in higher education, with higher payment for university teachers (Tsou & Kao, Reference Tsou and Kao2017; Wu & Lau, Reference Wu, Lau, Kirkpatrick and Liddicoat2019). On September 19th, 2018, then Premier Lai announced that for coping with globalization, Taiwan has to boost people's English proficiency and develop into a bilingual nation by 2030. Since then, a blueprint for this plan has been published by the National Development Council. The schemes introduced for promoting the bilingualization of Taiwan's educational system include: extending bilingual education to pre-school caretaking activities in the kindergarten curriculum, requiring a particular number of obligatory English-medium courses as integral to higher education, establishing all-English television channels, increasing English broadcasting programs, as well as cultivating friendly bilingual tourism environments (National Development Council, Taiwan, 2018).

While the government makes every endeavor to enhance international competitiveness through the EE policy and bilingual education development goals, English teaching and learning has long been part of Taiwanese people's daily life. Before the EE policy of requiring English as a compulsory subject in primary education, thousands of school pupils had already started learning English in preschools and the majority of people have been using some English at work or in daily life (Chen & Tsai, Reference Chen and Tsai2012). The ideologies of English are shaped by two driving forces: (1) the goals of the English curriculum in K-12 since 2001, particularly developing English communicative skills, fostering learning motivation, and promoting foreign cultures (Chien, Reference Chien2014); (2) an indispensable role of supplementary education, best known as cram schools or buxibans (Chou & Yuan, Reference Chou and Yuan2011). The latter does not come as a surprise, as cram schools have been prevalent in many East Asian countries such as China, Japan, and South Korea (Hu & McKay, Reference Hu and McKay2012). Liu (Reference Liu2012) has shown that studying at cram school appeared to have a positive correlation with Taiwanese students’ academic performance, yet scant attention has been paid to the overall impact of secondary English education in both formal and cram schools upon Taiwanese young learners’ English competence (Chou, Reference Chou2015).

The latest report by the National Development Council in Taiwan (2018) points out that the goal of developing a ‘2030 bilingual nation’ has evoked enthusiasm in learning, teaching, and using English in different domains. Nevertheless, the emergence of a ‘bilingual nation discourse’ may not only affect the education in Taiwan but also national identity. Many challenges of implementing bilingual education remain to be resolved: the lack of English teachers instructing non-English subjects, missing resources and infrastructure, and the thorny issue of using Mandarin Chinese as the next promising global language, a powerful regional language to demonstrate one's national identity (Ferrer & Lin, Reference Ferrer and Lin2021). English education in Taiwan in the coming ten years may undergo a rapid transformation; the linguistic landscape of Taiwanese English as an East Asian English variety may become more dynamic and pluralistic, being spoken and utilized in various contexts of communication.

Outside of the education sector, English features in Taiwanese lives in various ways, for example, in advertising (Chen, C. W.–Y. Reference Chen2006) and different media (such as the English-language newspaper Taipei Times and movies shown in cinemas in their original language with subtitles). We also find substantial uses of English in some workplaces, such as the medical sector, where diagnoses and communication between professionals often take place in English (Bosher & Stocker, Reference Bosher and Stocker2015). In addition, Go (2018; quoted in Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi, Bolton, Botha and Kirkpatrick2020: 548) reported uses of English by children with their parents and peers. Nevertheless, English in Taiwan remains largely underexplored, which provides an ideal backdrop for our study. Apart from studies on language planning and policies (e.g., Simpson, Reference Simpson and Simpson2007; Price, Reference Price2014), research output on English in Taiwan remains scant, is usually anecdotal, and, additionally, often already outdated (Hsu, Reference Hsu1994; Chen, C. W.–Y. Reference Chen2006). In one of the very few recent publications on English in Taiwan, Seilhamer (Reference Seilhamer2015: 376) describes the English use by his six female participants as ‘exud[ing] confidence, active agency, and indeed a sense of ownership [of English]’. This indicates that English is indeed actively employed by (at least) parts of the Taiwanese society, despite English having no official status within the country (see also Seilhamer, Reference Seilhamer2019).

Data

As we outlined before, previous research on English in Taiwan has largely focused on matters of language learning and teaching as well as language policy. To the best of our knowledge, no spoken corpus of English by Taiwanese speakers exists to date. In this article, we report the first results from a pilot corpus project with the title ‘English in Taiwan – Forms and Functions’. The project ultimately aims at compiling a corpus of English in Taiwan comparable to the SPOKE corpus (a 300,000-word corpus of Spoken Korean English; see Rüdiger, Reference Rüdiger2019). In the first stage of the project, a pilot corpus consisting of 19 interviews with 21 speakersFootnote 2 was collected. The interviews were conducted in October 2019 by the first author of this paper and followed the ‘cuppa coffee’ framework (Rüdiger, Reference Rüdiger, Christ, Klenovšak, Sönning and Werner2016), which ensured a relaxed atmosphere conducive to informal conversations. Participants were recruited with the help of academic staff at a major university and personal contacts, with subsequent snowballing to recruit additional speakers. All participants signed an informed consent sheet before the recording started. The overall recording time lies at a bit more than 13 hours (i.e., 795 minutes). In three cases, two speakers participated in the recording at the same time (triadic conversations), the rest of the interviews involved one Taiwanese speaker and the interviewer (dyadic conversations). The length of individual recording sessions ranged between 22 and 64 minutes (with the triadic conversations being on average longer than the dyadic ones). Most of the conversations were recorded in different cafés on or close to a major university campus in New Taipei City. In the following, we refer to this corpus as TASE (Taiwanese Spoken English corpus). An overview of the demographics of the corpus speakers is given in Table 1.

Table 1: Speaker demographics TASE

After basic orthographic transcription, the pilot corpus spans ~76,000 words produced by the Taiwanese speakers (the whole corpus, i.e., including interviewer speech and the international student [see footnote 2], amounts to 133,000 words). The corpus was subsequently tagged for two morpho-syntactic phenomena for which we also have results from the SPOKE corpus, that is, plural marking on the noun and the use of pronouns. This enabled us to draw on previously established tagging procedures and allows a comparison between the results for both corpora.

Comparing SPOKE and TASE

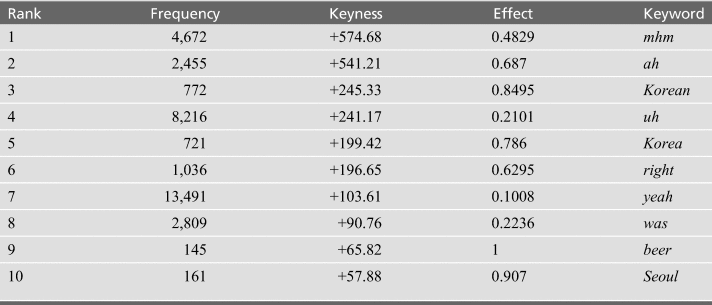

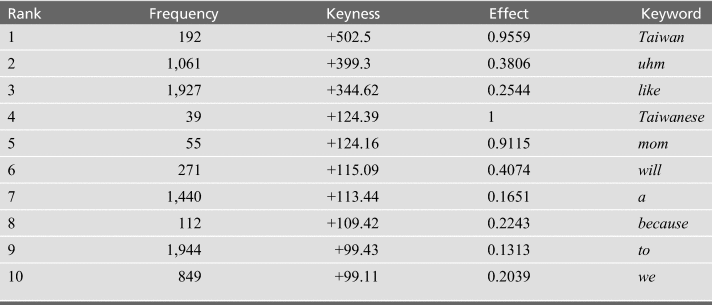

Using Antconc's (Anthony, Reference Anthony2018) keyword analysis tool to compare the pilot version of TASE with SPOKE, we find 54 keyword types in SPOKE (top ten reproduced in Table 2) and 104 keyword types in TASE (top ten reproduced in Table 3). It is of course not surprising that words like Korean, Korea, and Seoul are keywords in SPOKE and Taiwan and Taiwanese in TASE. Some keywords seem to stem from different thematic choices (beer in SPOKE and mom in TASE), even though both corpora were collected by the same interviewer, applying the same data collection and interviewing method. However, some keywords could be indicative of more fundamental differences between the two English varieties. In the following, we want to mention only three of the observations that stand out in this preliminary inquiry, all of which would warrant further in-depth quantitative and qualitative analysis.

Table 2: Top ten keywords in SPOKE (when compared to TASE; keyword analysis with Antconc; effect size measurement: difference coefficient)

Table 3: Top ten keywords in TASE (when compared to SPOKE; keyword analysis with Antconc; effect size measurement: difference coefficient)

First, SPOKE, but not TASE, has a surprising number of keywords which potentially function as backchannel responses (cf. Jefferson, Reference Jefferson1984; Peters & Wong, Reference Peters, Wong, Aijmer and Rühlemann2014) such as mhm, ah, right, and yeah. This might be an indication of different discourse-structuring strategies by South Korean and Taiwanese speakers of English; a preliminary observation definitely worthy of future research.

Second, Rüdiger (Reference Rüdiger2021), based on the SPOKE corpus, has shown how like is a firm part of the South Korean English repertoire and is used across the item's functional range (including its discourse-pragmatic functions). Despite the Korean speakers’ attested use of this lexical item in its various functions, like shows up as keyword for TASE (not SPOKE), on rank 3 nonetheless – definitely an invitation to have a closer look at both corpora to find out what Taiwanese speakers are doing differently.

Last but not least, we also find some function words as keywords in TASE, for example, the indefinite article a (rank 7). Indeed, an analysis of SPOKE has shown a low rate of indefinite article use (when compared to corpora of spoken American English, British English, and various ICE-corpora; cf. Rüdiger, Reference Rüdiger2019: 114–115). At first glance, Taiwanese speakers of English do not seem to share this characteristic. Other function words which are key in TASE are the multi-functional to (infinitive marker, preposition; rank 9) and the 1st person plural pronoun we (rank 10).

We hope to have shown here how productive this kind of comparison can be, even in its preliminary form and despite the current limitations at play (i.e., TASE being in its pilot stage). This provides ample pointers for the kind of research which we want to take up once the full corpus has been compiled. In the following two sections, we now turn to the results of the manual coding of plural markers on the noun and overall pronoun usage.

Plural marking on the noun

The primary language spoken by our informants, Mandarin Chinese, has practically no inflectional plural marking on nouns. Plurality is typically achieved by means of quantifiers, numerals, and context. The only exception is the suffix -men, which can attach to some human nouns, so that lǎoshī ‘teacher’ can become lǎoshīmen ‘teachers’, for instance in vocative use. Plural pronouns (see next section) also end in -men. However, -men cannot be used for inanimates (shū ‘book’ cannot be pluralized to *shūmen ‘books’) and cannot co-occur with numerals (*sān-ge lǎoshīmen ‘three teachers’) or quantifiers (*hěn dūo de lǎoshīmen ‘many teachers’), thus entirely eschewing the obligatory plural redundancy of other standardized Englishes. This makes morphological plural marking a marginal phenomenon in Chinese.

We focus here on cases of plural redundancy reduction, that is, cases where no plural marking (i.e., minus-plural marking; cf. Rüdiger, Reference Rüdiger2019: 47–48 for details on our terminological choice here) is found on a noun as the plural is already semantically entailed, either via specific lexical triggers preceding the noun (quantifiers like many, several, and all; numbers above one) or the discursive context (e.g., interviewer speech, common sense). For quantifiers and numerals, all instances were automatically retrieved from TASE via AntConc. The concordance lines were then manually examined to exclude irrelevant hits (e.g., lexical trigger not part of a noun phrase, unclear cases, non-count head of the noun phrase). In general, we applied the same annotation criteria as used for the analysis of plural marking in SPOKE to the TASE material (Rüdiger, Reference Rüdiger2019: 77). This allows a comparison between the two corpora, but we need to keep in mind that TASE is still in its pilot stage. The numerical results thus have to be interpreted with caution, particularly in cases where the overall number of instances is very low.

Quantifiers

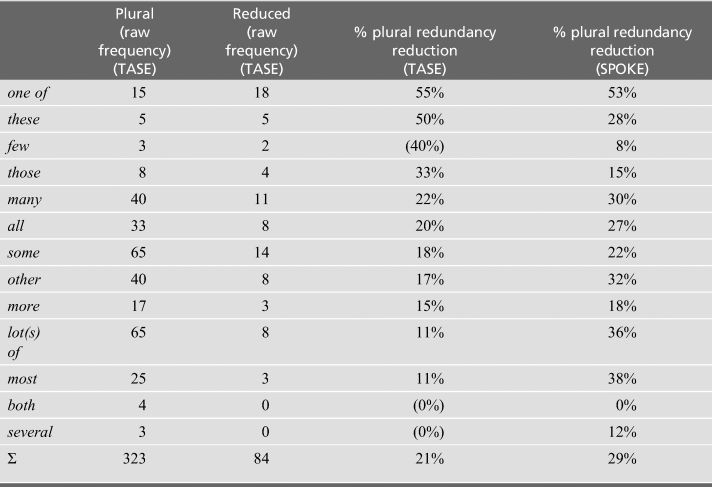

Altogether, we identified 84 cases of minus-plural marking on the noun after quantifiers in TASE (see Table 4). This involves instances like (1)–(3):

(1) I need to do many thing (TASE-005)

(2) I feel like one of the reason I like the movie is well because it's unreal (TASE-012)

(3) so we are (.) required to take these class of course (TASE-003)

The aggregated reduction rate for TASE across all examined quantifiers lies at 21% (based on 323 realized plural forms and 84 minus-plural markings after quantifiers).

Table 4: Overview plural marking after quantifiers (TASE) and % plural redundancy reduction (TASE and SPOKE) (round brackets indicate that the percentage is based on less than 10 overall occurrences)

Numerals

Minus-plural marking on the noun after numerals (above one) also does occur in TASE (see examples [4]–[6]) but is rather infrequent. The aggregated reduction rate after numerals in TASE lies at 7% (based on 222 realized plural forms and 17 minus-plural markings after numerals).

(4) I go there about like two time per week (TASE-002)

(5) so right we have like three convenient store per block (TASE-006)

(6) we have fifty-seven classmate (TASE-018)

A similar phenomenon occurred in SPOKE, where the redundancy reduction rate is also lower after numerals than after quantifiers (SPOKE: 29% → 15%; TASE: 21% → 7%).

Discursive context

The TASE corpus material additionally contains 1,036 plural nouns and 146 nouns with minus-plural marking (not preceded by a quantifier or numeral). In those cases, the plurality of the noun was already determined by the discursive context (uttered by the Taiwanese speaker or the interviewer; see examples [7]–[10]); for instance, in (7), the surrounding context clarifies that the speaker here talks about several cases of tasks being assigned spontaneously. In (9), the context clarifies that the speaker describes how infants in general produce sounds (and not a specific sound).

(7) but he uh he gives us assignment like randomly like (TASE-003)

(8) so we are facing like an overthrow [overhang] of teacher (.) and excess of teacher whereas we are lacking people in other fields (TASE-001)

(9) so they pronounce their sound with the lip (TASE-019)

In some cases, common sense led to a minus-plural marking reading of the data. In (10), the speaker describes her general movie preferences. It is rather unlikely that she likes to watch the same romantic movie over and over again and thus the concept referenced here is plural.

(10) I like romantic movie (TASE-012)

Based on the numbers given above, the plural redundancy reduction rate for nouns not preceded by quantifier or numeral lies at 13% (cf. SPOKE 21%).

In 88 instances, the noun did not bear plural marking, but it could not be determined with certainty whether the noun refers to a plural or singular referent. An example for this can be found in (11): it remains unclear, and indeed ultimately irrelevant, whether the speaker's boss and one colleague or several colleagues are travelling together.

(11) like my boss and my colleague sometimes they need to fly to uh Thailand or Vietnam or other country (TASE-019)

Looking at the reverse case of minus-plural marking, we find 86 ‘unexpected’ plurals (i.e., plus-plural marking on the noun). For example, in (12), the speaker refers to the obligatory PE class that students at the university have to take with the plural ‘courses’.

(12) it's a required courses (TASE-002)

Taking all plural forms in TASE into account (i.e., 323 following a quantifier + 222 following a numeral + 1,036 plurals in all other noun phrases), this amounts to a plus-plural rate of 5% (cf. SPOKE 4%).

Minus-Pronouns

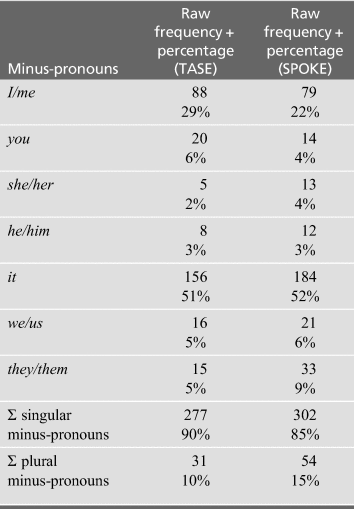

Chinese allows minus-pronouns in virtually any position (subject, object) as long as they are recoverable from context. Unlike in Korean, there are no politeness levels encoded in the Mandarin pronouns; neither are they subject to case marking. Their pragmatic and syntactic ‘value’ is, therefore, low. We find that the Taiwanese speakers, as represented in TASE, employ minus-pronouns when they are speaking English. The examples below show different kinds of minus-pronouns in subject position (first-person singular in [13] and [14], second-person in [15] and [16], and third-person neuter in [17] and [18]) as used by the Taiwanese English speakers in our data set. Altogether, 306 minus-pronouns occur in subject position in TASE.

(13) but in Taiwan Ø don't think we need that very much (TASE-009) (first-person singular I)

(14) Ø got a chance to have a interview (TASE-010) (first-person singular I)

(15) and you don't need to talk much (.) Ø just do it by yourself (TASE-018) (second-person singular you)

(16) oh Ø don't have convenient stores? (TASE-006) (second-person plural you)

(17) actually Ø can be even good for (TASE-009) (third-person singular it)

(18) mainly Ø is these kind of stuff or hotpots (TASE-002) (third-person singular it)

Minus-pronouns also occur in object position in TASE (n = 14):

(19) you have to do it otherwise it could curse Ø (TASE-007) (second-person singular you)

(20) you don't know Ø? (TASE-018) (third-person singular her)

(21) so I booked Ø I write a email to you (TASE-019) (third-person singular it)

The distribution of minus-pronouns in TASE, as illustrated in Table 5, differs only in some instances from that in SPOKE. We note, firstly, that the inanimate third-person singular it is the most prominent minus-pronoun in both datasets, accounting for more than half of the cases. The first-person singular follows, more obviously so in TASE, but still accounting for 22% in SPOKE. Overall, singular minus-pronouns appear with much greater frequency than plural ones, with 90% vs 10% in TASE and a similar 85% vs 15% in SPOKE (note that you is counted as singular in this computation).Footnote 5

Table 5: Minus-pronouns in TASE and SPOKE

The data presented here needs to be qualified somewhat, though. Firstly, the numbers presented in Table 5 are raw frequencies of minus-pronouns, and do not yet take into account plus-pronouns. The percentages refer only to the types of minus-pronouns within each corpus. Secondly, TASE is still in its pilot phase and is thus, with ca. 76,000 words, less than a third the size of SPOKE (300,000 words). Planned future data collection efforts will make the corpora more comparable in size.

Conclusion

With the increasing spread of English into locales of Kachru's Expanding Circle, the need for a better understanding of these varieties (both from a structural and sociolinguistic point of view) arises. To date, the bulk of large-scale English-language corpora has focused on Inner Circle and Outer Circle Englishes – the former benefitting from a variety of historical and synchronic corpora. In the Outer Circle, the International Corpus of English (better known as ICE) project has provided a usefully comparable set of data from a range of varieties (see Nelson, Reference Nelson, Nelson, Proshina and Davis2019). When it comes to the Expanding Circle, however, there is a dearth of comparable databases, which has a negative impact on our understanding of the structural features of these varieties.Footnote 6 The prominence of English in many such settings, especially in the larger East Asian context, suggests that the number of speakers of Expanding Circle Englishes is likely to continue growing rapidly. It is our conviction that in order to further our understanding of the English language system in all its variation, a broad selection of corpora from a variety of Englishes, regardless of their Kachruvian status, can only improve the state of research in World Englishes.

From a global sociolinguistic perspective, we also believe that scholarly attention given to Expanding Circle Englishes (‘norm-dependent’ varieties, in Kachru's terms) has the potential to legitimize these ways of speaking in a way that also legitimizes the speakers themselves. We here align with Seilhamer who notes that ‘ideologies privileging North-American accented English’ can most effectively be challenged by speakers ‘proudly, and even audaciously, assert[ing] the legitimacy of their English usage rather than apologizing for it’ (2019: 194–195). We hope that the scholarly recognition of Expanding Circle Englishes, also in the form of publicly available corpora, is a further supporting step into this direction.

Finally, while some might question the systemic relevance of data from Englishes that are spoken as a mere ‘foreign’ language in polities where it has few institutional roles, we submit that if the language is embedded enough within the speech community, then it deserves attention, especially so as increased opportunities for cross-varietal contact may well bring these varieties to international prominence. Research endeavors that account for the entire range of English variation are inherently valuable contributions to the entire field of World Englishes.

Acknowledgments

Jakob Leimgruber and Sofia Rüdiger gratefully acknowledge the DFG (German Research Foundation) funding for the pilot study (research grant LE 3136/4-1 and RU 2369/1-1). We are particularly thankful to our hosts and colleagues at Fu Jen University and our interview participants. We would also like to thank Franziska Ahlstich and Miriam Neuhausen for their help with transcription and tagging.

SOFIA RÜDIGER is a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Bayreuth, Germany, with a research focus on World Englishes, corpus linguistics, digital communication, culinary linguistics, and (historical) pragmatics. She is author of Morpho-Syntactic Patterns in Spoken Korean English (Varieties of English Around the World, 62, John Benjamins, 2019) and co-editor of Discourse Markers and World Englishes (special issue of World Englishes, 40/4, 2021). Email: [email protected]

SOFIA RÜDIGER is a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Bayreuth, Germany, with a research focus on World Englishes, corpus linguistics, digital communication, culinary linguistics, and (historical) pragmatics. She is author of Morpho-Syntactic Patterns in Spoken Korean English (Varieties of English Around the World, 62, John Benjamins, 2019) and co-editor of Discourse Markers and World Englishes (special issue of World Englishes, 40/4, 2021). Email: [email protected]

JAKOB R. E. LEIMGRUBER is currently lecturer at the University of Basel (Switzerland) and substitute professor at the University of Freiburg (Germany). His research foci include World Englishes, language planning and policy, and linguistic landscapes. He is particularly interested in the English found in Singapore, Taiwan, and the United Arab Emirates. He is the author of Singapore English (CUP, 2013) and Language Planning and Policy in Quebec (Narr, 2019), and co-editor of Multilingual Global Cities (with Peter Siemund, Routledge, 2021). Email: [email protected]

JAKOB R. E. LEIMGRUBER is currently lecturer at the University of Basel (Switzerland) and substitute professor at the University of Freiburg (Germany). His research foci include World Englishes, language planning and policy, and linguistic landscapes. He is particularly interested in the English found in Singapore, Taiwan, and the United Arab Emirates. He is the author of Singapore English (CUP, 2013) and Language Planning and Policy in Quebec (Narr, 2019), and co-editor of Multilingual Global Cities (with Peter Siemund, Routledge, 2021). Email: [email protected]

DR. MING-I LYDIA TSENG is an associate professor in the Department of English Language and Literature at Fu Jen Catholic University, Republic of China (Taiwan). Her research interests include academic literacy studies, second/foreign language learning and teaching, qualitative research methodology, and discourse analysis (particularly, critical discourse analysis and genre analysis). Email: [email protected]

DR. MING-I LYDIA TSENG is an associate professor in the Department of English Language and Literature at Fu Jen Catholic University, Republic of China (Taiwan). Her research interests include academic literacy studies, second/foreign language learning and teaching, qualitative research methodology, and discourse analysis (particularly, critical discourse analysis and genre analysis). Email: [email protected]