Quantifying maladaptive or potentially dysregulated patterns of eating as a food addiction, eating addiction or an eating disorder is an emerging topic of interest that, if supported, may have relevance for a variety of areas of health(Reference Brownell and Gold1). However, controversy and criticism exist in how to define maladaptive patterns of eating that are commonly referred to as food addiction, the distinction from other associated conditions (e.g. eating addiction, eating disorders, etc.), and the role such phenomenon may play in health problems such as obesity(Reference Gearhardt, Corbin and Brownell2–Reference Meule8).

For example, media coverage and clinical work with people with morbid obesity have promoted the concept of food addiction. While this term seems to be widely accepted in the general population, it is not as universally accepted within the scientific community. Scientifically sound research is necessary in order to be able to clarify the still open questions regarding the association between food and addiction.

Therefore, the purpose of the present paper was 3-fold: First, the current state of research on food addiction was reviewed; secondly, evidence for established criteria and concepts for addiction to food/eating is presented; thirdly, the potential relationships and distinctions between food addiction and recognised eating disorders were reviewed.

Current state of research on food addiction

The concept of food addiction refers to specific food-related behaviours characterised by excessive and dysregulated consumption of high-energy food(Reference Imperatori, Fabbricatore and Vumbaca9). Research on food addiction began in 1956(Reference Randolph10). However, much attention has been given to this concept in recent years as new methods, knowledge and an increasing number of studies have been carried out on both animal models and in human subjects in recent decades(Reference Fernandez-Aranda, Karwautz and Treasure11). Preliminary findings suggest an association between overweight/obesity, food and addiction(Reference Brownell and Gold1) which has recently led to some researchers(Reference Brownell and Gold1,Reference Gearhardt, Corbin and Brownell2) to put forward a concept of addictive-like eating as a potential explanation for overweight and obesity. Two main concepts have been used to quantify the addictive-like potential of food. First, research has focused on the chemical constituency of the food itself. This contention is based on similarities in patterns of food intake and consumption of drugs of abuse(Reference Gearhardt, Corbin and Brownell12) (e.g. in dopamine pathways(Reference Wang, Volkow and Logan13,Reference Gearhardt14) and in eating patterns(Reference Gearhardt, Corbin and Brownell2,Reference Ifland, Preuss and Marcus15) ). Specifically, individuals labelled as having food addiction frequently consuming processed foods that are energy dense and high in sugar, fat and salt(Reference Schulte, Sonneville and Gearhardt16,Reference Pursey, Davis and Burrows17) . Biological evidence suggests that the salt, sugars and fats contained within such highly palatable foods may have addictive potential via activating dopamine reward systems in the brain(Reference Gearhardt, Corbin and Brownell2). To this end, several different variables that may indicate the molecular, cellular and systems-level mechanisms(Reference Kenny18), reward mechanisms(Reference Kenny19–Reference Guzzardi, Garelli and Agostini23), specific components of food(Reference Pursey, Davis and Burrows17,Reference Gordon, Ariel-Donges and Bauman24,Reference Schulte, Avena, Gearhardt and Weir25) or diagnostic criteria for substance dependence in relation to eating behaviours(Reference Pursey, Stanwell and Gearhardt26–Reference Bumb, Weber and Kiefer28) as an addiction have been recently examined. The alternative contention has focused on eating behaviours, rather than food. This has led to the concept of maladaptive or dysregulated eating being more like an eating addiction(Reference Hebebrand, Albayrak and Adan29,Reference Ruddock, Christiansen and Halford30) . However, this view has been criticised as it does not clearly distinguish such behavioural patterns from other eating disorders, notably bulimia nervosa (BN) or binge-eating disorder (BED)(Reference Long, Blundell and Finlayson4). Given the consternation surrounding the validity and quantification of this phenomenon, some have questioned the clinical and scientific relevance of the concept of food addiction(Reference Ziauddeen, Farooqi and Fletcher5–Reference Meule8). To date, there is insufficient evidence to fully support or refute either contention. Given the rapidly growing body of evidence for both contentions and the potential clinical relevance of understanding how dysregulated patterns of eating contribute to adverse health outcomes, it stands that all interpretations of these data must take the preliminary nature of research on the aetiology of food addiction into account. That stated, the term food addiction has received the majority of research and clinical focus. Therefore, we have used this terminology as the preferred nomenclature throughout this review.

Assessment of food addiction

Fixed criteria to assess food addiction have been defined(Reference Gearhardt, Corbin and Brownell12) to more uniformly assess the concept and to ensure that the results among studies are comparable. This criterion is based on the concept that food addiction may represent an addiction; similar to addictions defined by the substance-related and addictive disorder criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)(31). Thus, the substance-related and addictive disorder criteria have been applied to food and a research instrument, the Yale food addiction scale (YFAS) was developed(Reference Gearhardt, Corbin and Brownell12). The YFAS version 2·0 is a thirty-five-item questionnaire with an eight-point response scale(Reference Gearhardt, Corbin and Brownell32). The YFAS 2·0 measures the eleven substance-related and addictive disorder criteria according to food and eating(Reference Gearhardt, Corbin and Brownell32). For the potential ‘diagnosis’ of a food addiction, at least two of the eleven substance-related and addictive disorder criteria must be fulfilled, and significant impairment needs to be present(31). The YFAS also measures impairment from eating behaviour(Reference Gearhardt, Corbin and Brownell12). The YFAS has been translated and validated in English(Reference Gearhardt, Corbin and Brownell12), German(Reference Meule, Müller and Gearhardt33), Italian(Reference Innamorati, Imperatori and Manzoni34), Spanish(Reference Granero, Jiménez-Murcia and Gearhardt35) and Japanese(Reference Khine, Ota and Gearhardt36). The YFAS is the most commonly used tool to assess food addiction(Reference Penzenstadler, Soares and Karila3,Reference Meule and Gearhardt37) . For this reason, the results of the YFAS are presented in this article. The validation study demonstrated internal reliability (α = 0·90) and convergent validity with other measures of problematic eating(Reference Gearhardt, Corbin and Brownell32).

Prevalence and correlates of food addiction assessed by the YFAS

Three systematic reviews of studies that have assessed food addiction using the YFAS have been conducted. These reviews revealed between twenty-five and sixty studies using human samples have been published between 2009 and July 2017(Reference Penzenstadler, Soares and Karila3,Reference Long, Blundell and Finlayson4,Reference Pursey, Stanwell and Gearhardt26) . These studies have reported prevalence from 0 to 25·7 % in non-clinical samples (e.g. adult general population, student samples)(Reference Penzenstadler, Soares and Karila3,Reference Long, Blundell and Finlayson4) and prevalence from 6·7 to 100 % in samples recruited from clinical settings(Reference Penzenstadler, Soares and Karila3). The definition of a clinical sample includes, e.g. individual with a current diagnosis of an eating disorder (prevalence: 57·6–100 %(Reference Penzenstadler, Soares and Karila3,Reference Long, Blundell and Finlayson4,Reference Pursey, Stanwell and Gearhardt26) ), or clinical prebariatric surgery sample (prevalence: 14–57·8 %(Reference Ivezaj, Wiedemann and Grilo38)). Compared to men, women showed significantly higher prevalence (3·0–14·0 v. 6·7–21·3 %)(Reference Pursey, Stanwell and Gearhardt26,Reference Carr, Catak and Pejsa-Reitz39,Reference Pedram, Wadden and Amini40) . In men, sexual minority orientation (e.g. gay, bisexual) was significantly associated with higher YFAS scores (prevalence: 1·83 v. 1·27 %)(Reference Bankoff, Richards and Bartlett41). Inconsistent results were found for food addiction prevalence and age(Reference Pursey, Stanwell and Gearhardt26,Reference Hauck, Weiß and Schulte42,Reference Schulte and Gearhardt43) . Higher prevalence has been reported in samples of black persons than in Hispanics or white individuals(Reference Carr, Catak and Pejsa-Reitz39,Reference Berenson, Laz and Pohlmeier44) . Additionally, a positive association with BMI has been reported(Reference Penzenstadler, Soares and Karila3). Evidence suggests that food addiction may be comorbid with eating disorders, especially BED and BN(Reference Penzenstadler, Soares and Karila3). Specifically, positive associations have been reported among binge-eating scores, difficulties in emotional eating regulation, restraint, disinhibition and hunger, night-eating scores, craving, impulsivity, reward sensitivity, depressive symptoms, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and food addiction overall scores(Reference Penzenstadler, Soares and Karila3).

Eating cognitions in food addiction

Eating cognitions common in food addiction may reflect a form of impulsive eating(Reference Collins, Lapp and Helder45), which may be related to addictive-like eating(Reference Murphy, Stojek and MacKillop46). For example, rigid control has been associated with higher BMI and disordered eating behaviour(Reference Westenhoefer, Stunkard and Pudel47,Reference Timko and Perone48) . Furthermore, binge eating is related to overweight and obesity(Reference Nightingale and Cassin49). Accordingly, the amount of binge symptoms have also been examined in relation to food addiction(31). Specifically, binges are defined as (1) consuming a quantity of food that is larger than what is considered normal in a discrete period of time, (2) a sense of lack of control, (3) eating faster than normal, (4) continuing to eat despite feeling uncomfortably full, (5) eating despite not being hungry, (6) eating alone and (7) feeling disgusted with oneself, depressed or very guilty afterwards(31). Further research is needed to elucidate this potential relationship, distinguishing if food addiction is orthogonal from other disorders that include binges, and if the binges observed in food addiction are distinct from objective and subjective binge episodes as part of BN or BED. In addition, morbid obesity is associated with reduced quality of life(Reference Kolotkin, Meter and Williams50). Future research is needed to further elucidate if food addiction is specifically related to the mental well-being component of quality of life in individuals with morbid obesity. If such a finding is supported, this may be of clinical importance and should be taken into account in prevention and therapy.

Two examples of studies conducted in Germany

YFAS 2·0 food addiction in a representative study in Germany

The first nationwide, representative study of the prevalence of food addiction was recently conducted in Germany(Reference Hauck, Weiß and Schulte42). Point prevalence of food addiction was 7·9 % within Germans, with higher rates in underweight (15·0 %) and obese participants (17·2 %) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. (Colour online) Prevalence of food addiction in three studies, according to BMI category (representative = study representative for the German population, athletes = German amateur endurance athletes).

Results of this nationwide study are similar to other research. For example, the prevalence of food addiction was comparable to previously reported rates within community samples collected from general populations worldwide(Reference Penzenstadler, Soares and Karila3,Reference Long, Blundell and Finlayson4,Reference Pursey, Stanwell and Gearhardt26) . Moreover, the overall point prevalence was also similar to the prevalence of alcohol use disorder (e.g. an established substance use disorder) in Europe (8·8 %) and Germany specifically (6·8 %)(51). Additionally, the highest prevalence rates in individuals with obesity are consistent with previous research(Reference Penzenstadler, Soares and Karila3,Reference Long, Blundell and Finlayson4,Reference Pursey, Stanwell and Gearhardt26,Reference Meule and Gearhardt52) . Finally, the elevated prevalence in underweight individuals was interesting. However, previous studies have also found a higher risk for food addiction in people with eating disorders, including the binge–purge subtype of anorexia nervosa(Reference Granero, Hilker and Agüera53,Reference de Vries and Meule54) . Thus, the elevated food addiction prevalence in underweight individuals may be due to an underlying eating disorder or other forms of disordered eating. This nationwide study adds much needed context to understanding that food addiction may be a contributor to overeating(Reference Hauck, Weiß and Schulte42), but it is not synonymous with obesity and not exclusively found in overweight/obese individuals. Therefore, food addiction may reflect a distinct phenotype of problematic eating behaviour(Reference Hauck, Weiß and Schulte42).

Food addiction in German-speaking endurance athletes

A recent study of amateur endurance athletes(Reference Hauck55,Reference Hauck, Schipfer and Ellrott56) examined comorbidity of food addiction, eating disorders and exercise dependence (e.g. another proposed behavioural addiction). The prevalence of food addiction was 6·2 %, of exercise dependence 30·5 % and of eating disorders 6·5 %. The highest prevalence of food addiction was found in underweight (9·8 %) and obese (23·1 %) subjects (see Fig. 1). Food addiction and exercise dependence were associated, thus suggesting potential overlap in underlying mechanisms for behavioural addictions(Reference Hauck55,Reference Hauck, Schipfer and Ellrott56) .

Transferability of criteria of addiction to food and/or eating addiction

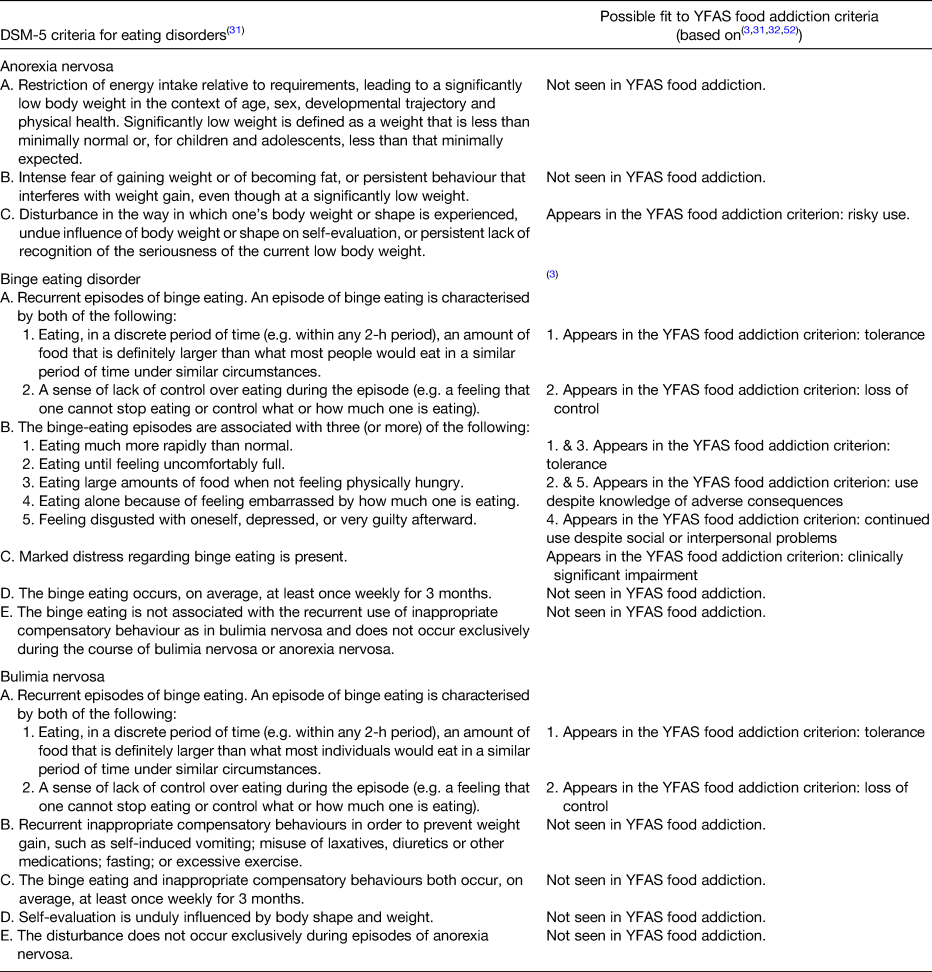

The second purpose of this review was to examine whether established criteria for addiction(31) may be used to quantify food addiction and/or eating addiction(Reference Gearhardt, Corbin and Brownell32). Table 1 shows the original DSM-5 substance dependence/addiction criteria(31). Using the DSM-5 paradigm as a mode for creating a food-specific criteria has been proposed(Reference Gearhardt, Corbin and Brownell32,Reference Meule and Gearhardt52) and a subsequent corresponding assessment has been created(Reference Meule57).

Table 1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) criteria for substance dependence, possible food addiction equivalents and plausibility of a transfer to food addiction

* The last column of the table was taken from a publication by Meule(Reference Meule57). However, it should be pointed out that we only agree with these statements if the following three points are noticed: First, food, within the concept of food addiction, cannot be seen only as a single substance, but as a complex composition of ingredients. By this, the substance dependence definition of the DSM-5 would not fit properly. Secondly, the process of eating (behaviour) should be considered. Thirdly, the criterion ‘withdrawal’ in our opinion is not transferable by plausible means.

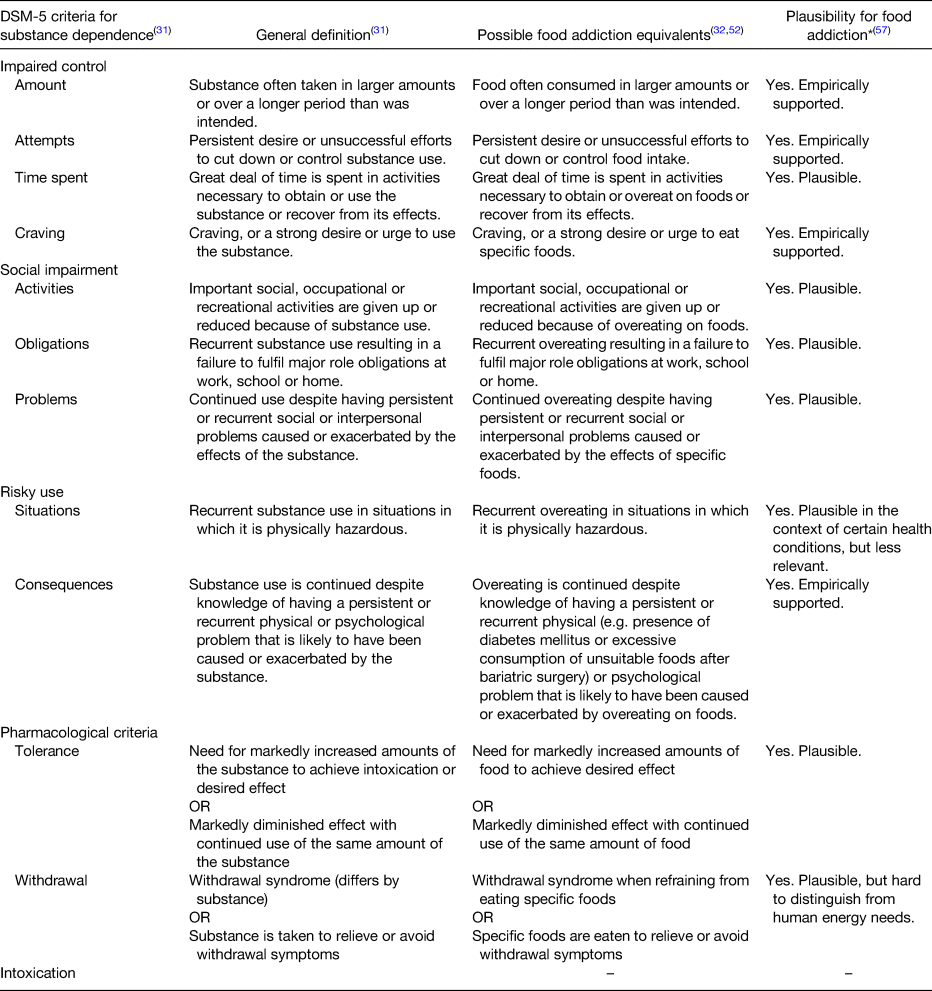

Alternatively, focusing on the behaviour of eating suggests that patterns described as food addiction may in fact be more similar to a behavioural eating addiction(Reference Schulte, Potenza and Gearhardt58–Reference Ruddock, Christiansen and Halford61). That is, fundamental differences exist between drugs and food(Reference Hebebrand, Albayrak and Adan29) and there is a lack of evidence that foods contain any addictive substance at all(Reference Ruddock, Christiansen and Halford30). Rather, an eating addiction denotes a set of behaviours and cognitions that represent maladaptive addiction-like patterns of eating(Reference Ruddock, Christiansen and Halford30). This paradigm has led to the development of the addiction-like eating behaviour scale. The addiction-like eating behaviour scale is a valid and reliable (α > 0·83) instrument to quantify the behavioural features of an eating addiction(Reference Ruddock, Christiansen and Halford30). It is a fifteen-item scale with responds on a five-point Likert scale that has a two-factor structure: increased appetite drive and low dietary control(Reference Ruddock, Christiansen and Halford30). However, few scientists favour the concept of eating addiction, and consequently, there are currently few publications available(Reference Hebebrand, Albayrak and Adan29,Reference Ruddock, Christiansen and Halford30) . Evidence for the non-substance-related disorder criteria from the DSM-5(31) and its transferability to addictive-like eating behaviour is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) criteria for non-substance-related disorders, definitions of the criteria and plausibility in the context of eating addiction

Potential relationships and distinctions between food addiction and eating disorders

The third purpose of the article was to examine the potential relationships and distinctions between food addiction and eating disorders.

Overlapping prevalence rates

Genetic similarities between compulsive overeating and substance addictions have been established(Reference Carlier, Marshe and Cmorejova62–Reference Davis, Zai and Levitan64), e.g. variants in genes encoding dopamine D2 receptor (e.g. Taq1 (rs1800497) allele of the ANKKI gene)(Reference Heber and Carpenter63) and transporter (e.g. SLC6A3, DAT1), and opioid receptor genes (OPRM1 gene)(Reference Davis, Zai and Levitan64). Additionally, several studies have reported food addiction prevalence between 86 and 100 % in BN(Reference Granero, Hilker and Agüera53,Reference de Vries and Meule54,Reference Meule, von Rezori and Blechert65) , 26 and 77 % in BED(Reference Granero, Hilker and Agüera53,Reference Gearhardt, Boswell and White66) and 50 % in the binge–purging subtype of anorexia nervosa (Reference Granero, Hilker and Agüera53), measured by Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale, Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire, Questionnaire for Eating and Weight Patterns - Revised and Eating Disorder Inventory-2. Despite such overwhelming overlaps with BN, BED and anorexia nervosa, however, there are not always complete overlaps with eating disorders. Another study found some overlap between the symptoms of food addiction and BED, however only when addictive traits in binge-type eating disorders are present(Reference Carter, Van Wijk and Rowsell67). This has been described as an addictive appetite model of binge-eating behaviour(Reference Leslie, Turton and Burgess68). The research today suggests that addictive-like aspects of eating may be present in some eating disorder variants. This is similar to the well-established overlaps of other addictions and eating disorders(Reference Bahji, Mazhar and Hudson69). Thus, further research is needed to further understand potential relationships among food addiction and binge-related symptoms of eating disorders.

Differences

Other researchers however argue that food addiction and eating disorders are two different constructs(Reference Hone-Blanchet and Fecteau70–Reference Davis72). That is, cognitive control and disinhibition of eating behaviour have been established in the aetiology of eating disorders(Reference Westenhoefer, Stunkard and Pudel47,Reference Stunkard and Messick73) ; however these cognitions are not evidenced in food addiction(Reference Meule, Müller and Gearhardt33). In addition, support for distinct behavioural and neurobiological evidence for food addiction phenotype has been found, thereby suggesting an addictive disorder rather than a subset of eating disorders(Reference Hone-Blanchet and Fecteau70). Thus, BED has been proposed as a psycho-behavioural disorder and food addiction as a biological-based disorder(Reference Davis72). Moreover, grazing patterns of overconsumption in individuals with food addiction has been reported(Reference Bonder, Davis and Kuk74), which indicates that overeating does not only occur as a binge, such as those in the diagnostic criteria for both BN and BED. Furthermore, food addiction has been reported after bariatric surgery(Reference Bonder, Davis and Kuk74,Reference Yoder, MacNeela and Conway75) when binges are not physiologically possible, but grazing is common.

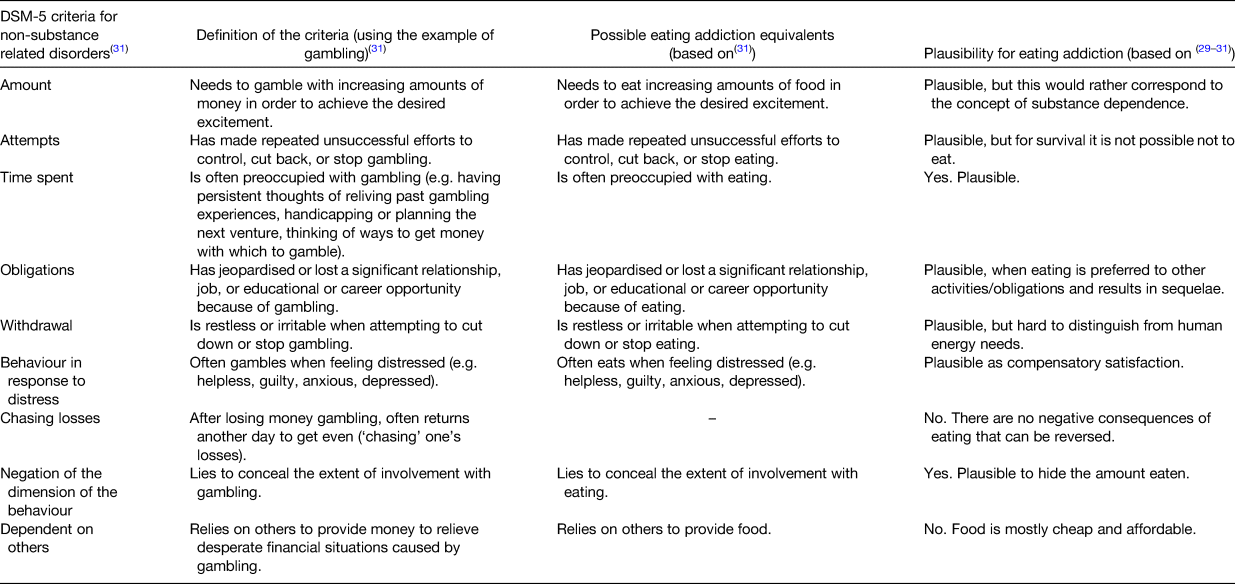

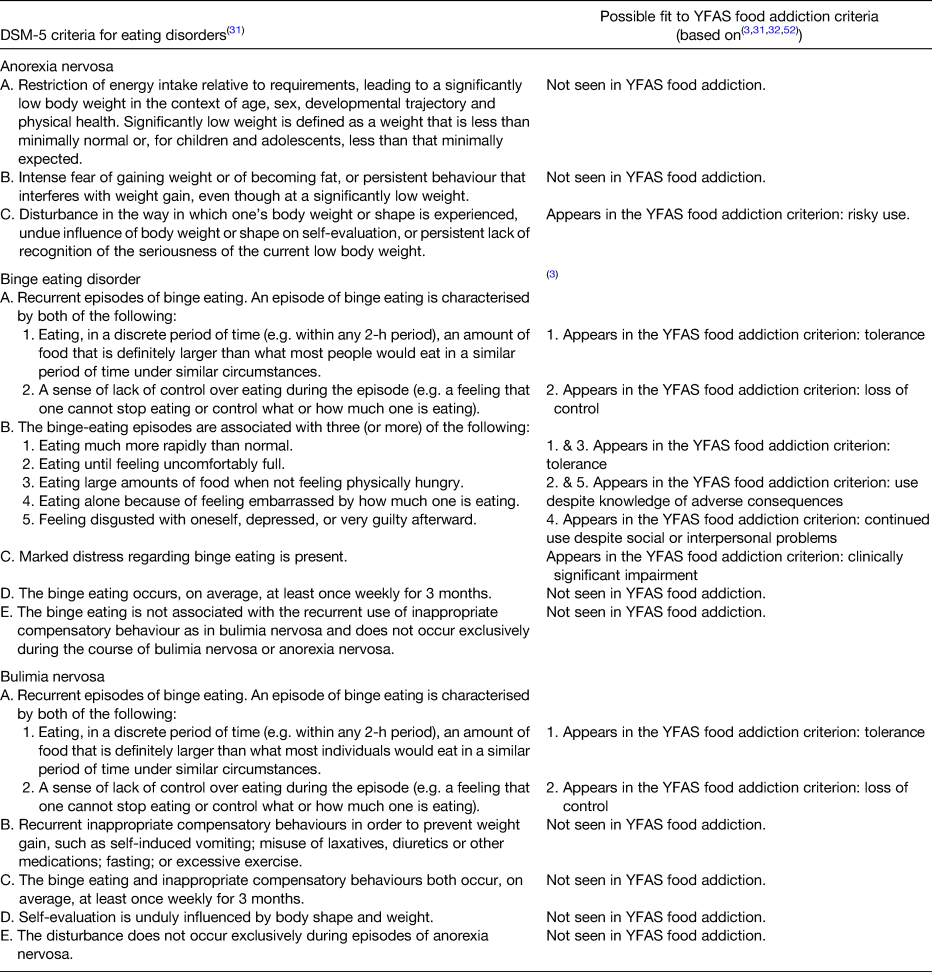

The evidence for food addiction's overlap with eating disorders

Some evidence exists to suggest that food addiction may overlap with the DSM-5 criteria for eating disorders(31) (see Table 3). That is, Table 3 summarises evidence for similarities of food addiction and each eating disorder variant. The extant literature suggests little evidence for the overlap with anorexia nervosa and food addiction. However, the tolerance, loss of control, consequences and problems subscales of the YFAS 2·0 may in fact be assessing several key aspects of DSM-5 criteria for BED. Finally, some evidence suggests that tolerance and loss of control aspects of food addiction may reflect DSM-5 criteria for BN(Reference Penzenstadler, Soares and Karila3,31,Reference Gearhardt, Corbin and Brownell32,Reference Meule and Gearhardt52) .

Table 3. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) criteria for eating disorders and potential fit to Yale food addiction scale (YFAS) food addiction criteria

Discussion

Food addiction is an emerging area of both clinical and research interest. The current review discussed several definitional and conceptual categorisations that have been put forth to quantify food addiction. However, the YFAS 2·0 concept predominates the literature. Similarly, evidence shows some similarities of food addiction with established eating disorders, particularly BED. Thus, the current review supports two main areas of contention that warrant much more research; considering food addiction as a substance-related addiction or a behavioural-related addiction and if food addiction is distinct from established eating disorders. Further research is needed to continue to delineate and clarify controversies about similarities and differences in food addiction with other concepts and established disorders.

First, substantial debate exists whether food addiction is more similar to substance dependence or to behavioural addictions. The DSM-5 criteria for substance dependence (Table 1) and for non-substance-related disorders (Table 2) were applied to food. Applying the DSM-5 criteria to addictive-like eating suggests that both concepts, the concept of substance dependence (food addiction) and the concept of non-substance dependence (eating addiction), may fit. Specifically, food addiction may reflect more criteria for substance dependence of the DSM-5 (Table 1) than eating addiction meets non-substance dependence criteria (Table 2). Recent systematic reviews also support a better fit for the concept of substance dependence, primarily due to the numerous studies that have established brain reward dysfunction and impaired control in food addiction(Reference Gordon, Ariel-Donges and Bauman24,Reference Schulte, Potenza and Gearhardt58) . Nevertheless, it should also be noted that some evidence suggests that it may be plausible for most of the DSM-5 criteria for non-substance dependence disorders to quantify food addiction (Table 2). This is consistent with the behavioural addiction perspective of some researchers(Reference Penzenstadler, Soares and Karila3,Reference Hebebrand, Albayrak and Adan29) . The plausibility of an eating addiction should be examined more closely in future studies.

Secondly, the current review of the literature also questions whether food addiction and eating disorders overlap or are distinct phenomena. After comparing the YFAS-derived criteria for food addiction and the criteria for eating disorders (see Table 3), food addiction and eating disorders seem to share several criteria, but do not completely overlap(Reference Penzenstadler, Soares and Karila3,31,Reference Gearhardt, Corbin and Brownell32,Reference Meule and Gearhardt52) . Thus, the evidence to date may suggest that they may be distinct phenomena. Specifically, Table 3 shows that the criteria for the two eating disorders BED and BN correspond more closely to the criteria for food addiction, than do the criteria for anorexia nervosa. However, there are also fundamental differences between eating disorders and food addiction, such as the presence of compensatory behaviours in BN but not in BED or food addiction(Reference Meule, von Rezori and Blechert65). Thus, eating disorders and food addiction may share similar traits but are not congruent. Further research is necessary to clarify ambiguities among food addiction and eating disorders. For example, applying research domain criteria(76) is necessary to examine if food addiction demonstrates key genetic, behavioural and physiological differences from each eating disorder variant in positive and negative valence systems, cognitive systems, social processes, arousal and regulatory systems, and sensorimotor systems domains. Establishing such differences would greatly inform a more precise definition of food addiction that may also contribute to an improved prevention and therapy options.

Conclusion

Addictive-like eating may manifest through repeated consumption of highly palatable, highly processed complex foods, typically containing high amounts of energy, sugar and fat. Evidence exists for this specific pattern of eating to be characterised as behavioural or substance dependence. While the evidence supporting a food addiction concept dominates the literature, it is currently premature to draw definitive conclusions for a better fit of the substance use disorder concept (food addiction, see Table 1) or the behavioural addiction concept (eating addiction, see Table 2). Superficial evidence suggests that food addiction may be associated with overweight and obesity, but causal inferences have not been established to date. Additionally, food addiction does not seem to match with the established eating disorders (see Table 3). Rather food addiction may represent a distinct pattern of disordered eating or a subtype of an already existing eating disorder, such as BED. Prevention and therapy concepts relevant to obesity and eating disorders may be able to be extended to food addiction. Specifically, such interventions guided by the addiction model of food and eating behaviour may offer novel, more individualised treatment approaches(Reference Pursey, Davis and Burrows17,Reference Avena, Gearhardt and Gold77) . Future studies with clear definitions and classifications of food addiction and eating addiction, as well as similarities and differences between food addiction and eating disorders are needed.

Limitations

This review has summarised the current understanding of food addiction. However, this review is limited by several factors. First, the extant research is largely cross-sectional and therefore no aetiology of food addiction may be evidenced. Secondly, little evidence exists to suggest appropriate and effective treatment techniques specific to food addiction. This further confuses the delineation of food addiction from other established disorders, such as BN and/or BED. Thirdly, the lack of scientifically established and agreed upon diagnostic criteria severely limits the ability of existing studies to provide adequate comparisons and insights into the phenomenon of food addition. Finally, historical records are lacking to indicate the potential role of culture and/or the changing patterns of food processing and modern food production in the aetiology of food addiction. Further research and clinical work are needed to identify causal factors, treatment approaches and psychological, physical and social impacts of individuals with food addiction.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Authorship

C. H., B. C. and T. E. wrote and approved the manuscript. It is a summary of an invited presentation of C. H. to the International Early Research Championship in the Nutrition Society Winter Meeting 2018.