INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

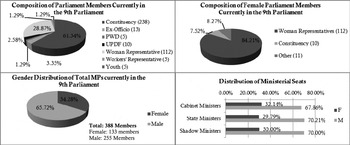

Thanks to constitutional mandates, women currently occupy around 34% of seats in the Ugandan Parliament. Women Representatives make up about 29% of total MPs and about 84% of all female members of Parliament. Almost 8% of women in the Ugandan Parliament are in mainstream Constituency seats, and another 8% are in reserved seats for women in Special Populations categories. Women also have a sizable share of Cabinet, State Minister and Shadow Minister appointments. Figure 1 shows the composition of the Ugandan Parliament.Footnote 1

Figure 1. Composition of the Ugandan Parliament.

The causal link between an increase in the number of female legislators and increased attention placed on pro-women legislation has been extensively studied. Proponents of critical mass theory have long argued that there is a positive association between the number of women legislators and the likelihood that these women will advance women's interests through gender-conscious legislative measures. These researchers have argued that as the number of women legislators rise, they are able to promote the interests of women by forming strategic coalitions, overcoming tokenism, and compelling other legislators to recognise the need to focus on women's issues and advance women-friendly legislation (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967; Saint-Germain Reference Saint-Germain1989; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999; Bratton Reference Bratton2005). Some studies have confirmed that women share distinct policy preferences that are conceived from shared gender experiences and perspectives (Reingold Reference Reingold1992; Wängnerud Reference Wängnerud2000; Lovenduski & Norris Reference Lovenduski and Norris2003; Swers Reference Swers2004).

Substantial evidence, however, casts doubt on the absolutist view that descriptive representationFootnote 2 will automatically lead to substantive representationFootnote 3 for a host of reasons. Women are not monolithic. The essentialist argument that all women are similar and that they will always act and behave in support of a feminist agenda is misleading. Women's class, age, ethnic background and party affiliation may hinder the formulation of a collective legislative agenda (Dodson & Carroll Reference Dodson and Carroll1991; Vega & Firestone Reference Vega and Firestone1995; Celis et al. Reference Celis, Childs, Kantola and Krook2008; Franceschet & Piscopo Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2008; Childs & Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009). Women (and men) need to have gender consciousness, or a sense of rejection of existing power relations and socially constructed gender roles, as a precondition to supporting the interests of their female constituents (Schreiber Reference Schreiber2002; Bierema Reference Bierema2003). Having gender consciousness, rather than just being female, is critical in working towards feminist outcomes.Footnote 4 Gender consciousness is the common denominator among female and male change agents who believe in, and desire, the advancement of a woman-friendly policy agenda.

Scholars argue that gender consciousness is an important link between gender identity and political action and policy preferences (Gurin Reference Gurin1985; Conover Reference Conover1988; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Hildreth, Simmons, Jones and Jonasdottir1988; Tolleson-Rinehart Reference Tolleson-Rinehart1992). However, while having gender consciousness may affect thinking, it may not always result in action, since action often incurs a heavy political and personal cost (Bierema Reference Bierema2003). Snell & Johnson (Reference Snell and Johnson2004) differentiated between having private and public gender consciousness as a spectrum along which women (and men) translate their private feelings of discontentment into actions. Franceschet et al. (Reference Franceschet, Krook and Piscopo2012) recognised the existence of two different stages of substantive representation. The first stage occurs when a representative acts on her gender consciousness and beliefs by formally and informally seeking to gender the policy process and the policy agenda. This takes several forms including introducing bills, networking with female and male allies to strengthen their position, debating positions formally and informally, and advocating for passage of bills. The second stage occurs when a representative succeeds in advancing policy measures and in gendering the policy outcomes. Success in the latter, however, is a function of a complex, multifaceted and dynamic process that occurs within and outside Parliament. It is the result of the interplay of agency of different critical actors with legislative structures within and outside Parliament.Footnote 5

Even when women (and men) have the will to advance a women-friendly policy agenda, it cannot be assumed that their actions will always translate into successful outcomes. Contextual factors within and outside the legislative Chambers may hinder the behaviours and actions of MPs (Childs & Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009). The persistence of patriarchal values, absence of support networks, and lack of an enabling political, economic and cultural climate may adversely affect the effectiveness of female MPs as well as stifle their abilities to support policy issues that are important to them. Internal and external contexts may limit the ability of women legislators to translate their priorities into policy initiatives. Rules and norms within the legislature and biases towards men's experiences and authority often hinder attempts to include women's concerns and perspectives in the policymaking process (Hawkesworth Reference Hawkesworth2003). An increase in the number of women legislators does not always lead to their empowerment and their ability to freely express and advocate for issues of concern to them. Instead, these women may feel pressured by the gendered process and structures to conform to positions taken by men and to silence their own voices (Hawkesworth Reference Hawkesworth2003). In addition, a rise in women's numbers may trigger a backlash and yield contradictory outcomes. Indeed, in some cases, an increase in the number of female legislators has led male legislators to employ obstructionist strategies in order to defeat women's policy initiatives and keep women marginalised and outside the circles of power (Carroll Reference Carroll2001; Hawkesworth Reference Hawkesworth2003). Quotas may reinforce these outcomes by propagating the common misconception that women earned entry into the legislature based on their gender and not on their merit.

In addition, women's effectiveness can be weakened by patronage politics, which remains a strong feature of the Ugandan Parliament. O'Brien (Reference O'Brien, Franceschet and Piscopo2012) argues that in Uganda's case, Women Representatives campaigned to ‘garner the approval of a small number of elites rather than a district wide constituency’ (p. 59). This process allowed patronage politics and wealth to have an impact on the election of the Women Representatives (Goetz Reference Goetz2002). For example, Josefsson (Reference Josefsson2014) noted that Women Representatives tend to be more loyal to the regime than other male and female members of Parliament. The trend may be attributed to the increased entrenchment of party politics. It may also be due to the stigmatisation and the ‘label effect’ women feel when they publicly affirm an exclusive interest in gender issues, (Franceschet et al. 2012).

The link between women's descriptive and substantive representation has been the subject of numerous investigations with many pointing to inconclusive findings. There seems to be a consensus, however, that the quota system, despite its drawbacks, remains one of the most effective tools for change, because of its potential to normalise women's presence and to challenge women's relegation to a separate sphere (Tripp Reference Tripp2003; Franceschet & Piscopo Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2008; Josefsson, Reference Josefsson2014).

In this study, we ask the following questions: To what extent did increasing women's numbers in Parliament normalise women's presence, improve male–female relationships, and reconfigure women's status? How do women act and perform on the floor of the Chamber? Answers to these questions have significant implications for deepening our understanding of the process that leads to cracks in the gender ceiling within formal institutions.

The current study reveals a definite change in gender roles and relations as well as a visible and active agency exercised by female MPs within the Ugandan Parliament. The spark was lit by the quota system, and the change was an unintended consequence of President Museveni's Affirmative Action policies.

A decade ago, a very different picture characterised the Ugandan Parliament. Tamale (Reference Tamale2000) argued that affirmative action is a ‘hollow victory’ that failed to change gender relations in the Ugandan Parliament, in that it had failed to activate the agency of women. On the Chamber floor, women acted with ‘reticence and diffidence’ (p. 13), and remained complacent in their own subordination, unable to leverage their role in Parliament or even engage in analysing their position and question the gender implications of proposed legislation (Tamale Reference Tamale2000). Goetz (Reference Goetz2002) agreed that the political value of Affirmative Action was eroded by the exploitation of women's votes as ‘currency’ or a ‘vote bank’ by the National Resistance Movement and its patronage system. Women's lack of political autonomy and their functioning under the thumb of an authoritarian party undermined their effectiveness and halted the progress toward constitutional commitments (Goetz Reference Goetz2002). Tamale (Reference Tamale2000) described a very chilly picture where women's bodies defined their identity within Parliament, and their role as Parliamentarians was relegated to a secondary status. She reported female MPs’ accounts of unwanted sexual and physical contact initiated by male legislators, and argued that women, for the most part, dealt passively with sexual harassment, which in turn affected them psychologically, increased their consciousness of their subordinate position and intensified their ‘feelings of belittlement’ (p. 13). The internalisation of their own objectification ultimately undermined their political efficacy. Social interactions of male and female legislators were tainted by a high level of gender inequality, which was deeply rooted in the fabric of Parliament's institutional structures (Tamale Reference Tamale1999).

Our study indicates that a significant change has occurred in the way female (and male) MPs in the Ugandan Parliament perceive each other and themselves. The Ugandan Parliament has undergone and continues to experience a profound transformation, one where there is a new internal frame of reference for gender within Parliament, one in which most female MPs express a sense of empowerment, self- and collective-efficacy, one where women's leadership and agency is valued, respected and acknowledged by both men and women.

We define the ecology of gender as the intersecting web of interrelationships between male and female Parliament members, their institutions and the environment within and outside Parliament. Our findings reveal that within the walls of Parliament, there are important changes in the socially constructed ecology of gender, with an erosion in the degree to which different roles, expectations and structures are ascribed to males and females based on biological sex.

These findings extend Wang's description of female MPs in the Ugandan Parliament and their ability to navigate restricted political space to advance pro-women legislation (Wang Reference Wang2013). The political space is growing for women MPs and they are actively participating in redefining its contours and boundaries. The findings also parallel a trend observed in Wyrod's (Reference Wyrod2008) study of a low-income neighbourhood in Kampala, which found that there has been a transformation in the gendered landscape outside the walls of Parliament. He documented the rise of a new ‘configuration of gender relations’ in urban Uganda that incorporates elements of human rights, while still retaining many aspects of traditional gender relations. A majority of men and women interviewed for his study clearly recognised that women's access to education and jobs is critical to development, and that men and women have shared rights and should work collaboratively. Poverty and universal discourses about gender equity and equality have undoubtedly shaken the very foundation of male authority in Uganda, as it became difficult to live up to the cultural ideal of the sole male provider and preserve exclusionary male authority in the home. Acceptance of women's participation in gainful employment and collaborative decision making in the home are both becoming mainstream. Gender relations in Uganda's urban society are shifting, although reservations still exist about property ownership and inheritance rights (Wyrod Reference Wyrod2008).

STUDY METHODOLOGY

Data were collected from several sources, including a survey of legislative members; a variety of public records including the Parliament's debates on women-centred bills and media coverage; in-depth semi-structured interviews with female members of Parliament, and a final meeting with male and female legislators to share survey and interview findings, and to identify actions to address challenges legislators face in trying to advance a women's agenda. Data were collected in 2013–2014. A hard copy of the questionnaire was hand-delivered to every legislative office. Fifty-eight completed surveys were returned (out of 383). We requested interviews with female MPs who are members of the Ugandan Women's Parliamentary Association (UWOPA), and 18 semi-structured interviews were conducted with female MPs. Although the pool of interviewees was dominated by Women Representatives, one Constituency Representative was interviewed. An invitation to participate in a meeting to share findings of the survey and interviews was sent to all members of UWOPA, and 15 male and female legislators participated in the final meeting. Quantitative data were tabulated and recorded. All interviews were recorded, transcribed, coded and interpreted to compare with the quantitative data collected from the surveys.

PROFILE OF STUDY PARTICIPANTS

Survey Respondents

Thirty-six per cent of survey respondents were women and 64% were men. This is representative of the composition of Parliament which includes 35% women and 65% men. Eighteen per cent of survey participants were born in the 1950s; 32% in the 1960s; 39% in the 1970s and 11% in the 1980s. Average age was 48 years old for both men and women participating in the survey. Age of Parliament members participating in the survey is representative of the demographics of Parliament where the average age is 50 years old for both men and women.

Seventy-three per cent of male respondents were Constituency Representatives; 3% Youth Representatives; 3% People with Disabilities Representatives; and 12% Unknown. Fifty-two per cent of female participants in the survey were Women Representatives; 8% Constituency Representatives; 28% Unknown; 8% Workers Representatives; and 4% Representatives of the Ugandan Defence Forces.

As for party affiliation, 60% of respondents belonged to the National Resistance Movement (NRM); 10% to the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC); 7% to the Uganda People's Congress (UPC); 2% to the Democratic Party (DP); 7% to the Uganda People Defence Forces (UPDF) and 12% were Independent. While gender representation was almost equal from the NRM and FDC parties (51% women, 49% men; and 50% women and men; respectively); the gender composition of representatives from other parties was overwhelmingly male; (UPC = 75% male and 25% female; Independent = 71% male and 29% female; DP = 100% male; and UPDF = 80% male and 20% female).

Interviewees

Interviewees were all females whose ages ranged from those born in the 1950s (14%); 1960s (50%); 1970s (22%) and the 1980s (14%), with an average age of 49 years old. With the exception of one interviewee, they were all holders of post-secondary degrees. Seventy-two per cent of interviewees were Women Representatives; 14% were Youth Representatives; and 14% were District Representatives. We consider the sample representative of the demographic composition of women Parliament members where 83% of women were Women Representatives; 9% were District Representatives; and 8% were other Special Populations including Youth Representatives. Twenty per cent of the interviewees served in a leadership capacity in Parliament including Committee Chairs and Vice Chairs, and 20% served in leadership capacity in UWOPA. With respect to party affiliation, 50% of interviewees belonged to NRM; 22% to FDC; 7% to UPC, 7% to DP; and 14% were independent.

Meething participants

Meeting participants were primarily members of UWOPA. UWOPA is inclusive of all female members of Parliament and is open to male members who serve as Associate or Honorary members. Currently, there are 19 male members of UWOPA. The meeting was held to share study findings. Members who attended were over 80% females. Although males were less than 20% of the meeting participants, they vocalised their perspectives on sexual harassment in Parliament and asserted their conviction that it has becomes an isolated phenomenon that is a remnant of the past.

FINDINGS AND RESULTS

A Women-Friendly and Respectful Climate

An overwhelming majority of both male and female MPs believed that the climate in Parliament was respectful and woman-friendly, 88% and 84% respectively (see Figure 2). There was no disagreement with this statement. A greater percentage of females than males responded neutrally to this statement. This may point to a general feeling of self-consciousness and responsibility by women MPs to make the climate women-friendly and respectful.

Figure 2. Climate of Parliament.

In interviews, the majority of female MPs agreed that male MPs respected strong females who carried themselves with dignity and self-respect and that women's leadership was valued and acknowledged within Parliament and, in some instances, more valued than men's leadership. They attributed this phenomenon to the belief that women have been ‘outperforming men’ on the Chamber floor, i.e. they have been effectively debating policy issues and advancing their arguments with vigour and conviction. There was general agreement that once females attained leadership positions, they were respected and their contributions were appreciated. Several interviewees pointed to the fact that women are heading key ministries such as the Ministries of Finance, Education and, previously, Health as an indication that female leadership is valued.

Women's leadership is valued, actually more valued than even (that of) men … people tend to put more trust in women … they know women (can succeed) when they are determined to push an issue. (Female MP)

Women's leadership is really valued … most of the committees are being led by women. (Female MP)

An Ability to Voice Opinions and Positions on an Equal Footing

A majority of female MPs (64%) and males (91%) agreed that all MPs engage equally in vocalising their positions (see Figure 3). There is a general consensus that the climate in the Ugandan Parliament allows males and females to voice their opinions equally, that there is space in Parliament and in committees to debate freely, and that parliamentary mechanisms to support equal participation have been improving.

The culture (of Parliament) allows both male and female to say their views the way they feel, to represent their constituency in the way they feel they should. (Female MP)

I feel empowered to introduce and move forward the policy priorities of my constituents. (Female MP)

We are all given the same opportunity; after being sworn in as a member of Parliament, we all have equal rights as our colleagues, the men. We debate freely depending on the knowledge you have on a particular subject. (Female MP)

Figure 3. Equality of engagement.

A Sense of Empowerment

A majority (84%) of female MPs agreed that they feel empowered to introduce and move forward policy priorities of their constituents (see Figure 4). A smaller percentage of males (76·6%) agreed with this statement. The expression of self-efficacy and empowerment is critical, and rejects the portrait of women MPs as passive, complacent and lacking agency. Bandura's (Reference Bandura1982) work on the relationship between self-efficacy and performance leads us to conclude that feelings of self-efficacy expressed by female MPs are likely to impact their behaviour and affect their agency. Obviously, female MPs may value smaller accomplishments more than their male counterparts, or feel empowered simply by having a seat at the table.

It is an accepted fact that women can be politicians, that it is okay for women to be politicians and go to Parliament … we have broken through that barrier. (Female MP)

Figure 4. Empowerment.

Female MPs not only expressed self-efficacy (Bandura Reference Bandura1982), but also collective-efficacy, or a sense that they are able to succeed collectively. They expressed a collective identity as female MPs and felt that a unifying organisation, the Caucus, fuelled their collective-efficacy.

There is definitely gender identity. We normally sit down and caucus as the Women's Parliamentary Association and we vote along those lines. Where issues of women are concerned, we go beyond political boundaries, party lines, and we unite because we are fighting for the same cause, be it a position, be it the ruling party; you are a woman. You know what affects a woman, so we work together. (Female MP)

A new and different portrait emerges of female MPs who are able to come together, transcend differences and unite to form a strategic bloc to advocate for women's issues. The strategies utilised by female MPs go beyond those found in earlier studies, which indicated that women had to negotiate limited space, and battle internal and external demons of patriarchy that paralysed them and rendered them ineffective.

We all have different interests when we come here, but what brings us together is a common women's agenda, and when it comes to an issue of women, women rally together. (Female MP)

We agree that when it comes to issues of women, let us be one, let's put aside our political differences. (Female MP)

We represent women, we want to see policies which can favour a woman. (Female MP)

Unlike earlier findings in the research literature, female MPs demonstrated not just a gender consciousness, but an understanding of issues that are traditionally not seen as women's issues, e.g. budgeting, and the implications of policies they help pass for their female constituents.

When it comes to budgeting, women make sure that the issues have to be pushed because they concern women … The women legislators said that we cannot pass this budget, not until the budget has been questioned somehow, because the reason was that the Maternity Health Bill has to be facilitated. (Female MP)

The one (bill) on water, when it came to the house, women pushed it and said ‘No, water cannot be taxed; when you tax water, you are affecting mothers’ … So, I agree, when it comes to legislative policies (affecting women), women pushed for them. (Female MP)

The Ugandan Women's Parliamentary Association (UWOPA) provided a critical organising force for female MPs and their male allies. Women were able to discuss issues amongst themselves, share their experiences, and develop ideas on how to enhance female participation and effective leadership across a number of areas. UWOPA also allowed the women to work to improve gender-responsiveness and sensitivity of the legislative process, as well as to network, mobilise resources and disseminate information. In their interviews, several female MPs emphasised the importance of UWOPA in bringing women MPs together to collaborate on common causes despite their differences in party ideology.

We have a strong umbrella … UWOPA; UWOPA is strong in terms of coordination and mobilisation of … activities as women. It's a link between us and the public outside, and then also within here, it brings us together. (Female MP)

Female MPs also cited UWOPA's role in providing women with the training opportunities that they need. One MP even pointed to the fact that UWOPA empowers women and unites them.

We work together to identify issues concerning women, and when there's a problem, we come together, and organise a workshop so that we unite to drive our points. (Female MP)

What helps us is, again, the forum that has brought us together. If there is an issue that is a serious women's issue, we come forward. UWOPA has helped us. (Female MP)

Empowered by UWOPA, Female MPs are able to effectively engage male allies (i.e. associate and honorary members of UWOPA), and use sophisticated political strategising and manoeuvring. They are increasing their ability to form alliances with male MPs.

We have to lobby the men to support us so that issues go through. (Female MP)

Whenever there is anything discussed on the floor of the house and women stand up and say ‘yes,’ we also get a number of men who support our issues and they have always been behind us. (Female MP)

We have men who sympathise with us … Men that register in our forum of women and participate very actively, they contribute and they help. (Female MP)

Every woman MP who was interviewed recognised the importance of having a female speaker in allowing women MPs greater opportunity to voice their opinions and making sure women were given a chance to speak on the floor of Parliament. Speaker Rebecca Kadaga has also understood the issues women MPs deal with such as work-life balance, and agreed to have a daycare centre at Parliament.

The speaker is the patron of the Uganda Women's Parliamentary Association, so whenever we see anything that affects women, we run to her and ask for her support as a woman and normally she's very effective and responds positively. (Female MP)

Having our speaker has also helped … when she thinks an issue is very critical … she will … push … for an issue she believes in. (Female MP)

The speaker has played a very big part … she has pushed for more women to be leaders. (Female MP)

Kadaga as the speaker has really helped women members of Parliament and has really helped us to … build our capacities. (Female MP)

The Speaker also served as a critical role model for women, changing their perception of their competencies, place and role. A female MP noted that the Speaker's excellent performance has improved the status of female leaders, and her competencies have encouraged both men and women to appreciate their own positions.

The Speaker has outdone all the other speakers that have been there before in terms of performance, so there is no question about our performance as leaders. (Female MP)

Interviewees agreed that since the Speaker and female MPs, in general, have outperformed men as leaders, this has helped reduce the likelihood that female MPs will be viewed as sexual objects. One interviewee said that stereotyping in Parliament has been eliminated because female MPs have been able to prove their competency. Self-efficacy and collective-efficacy have naturally given birth to improved performance by women in their legislative role.

Traditionally women are considered of low class, not about to lead. Interestingly, when I go to Parliament, I realise that women have the same potential as men and they do very well in their legislative work. (Female MP)

An Equal Opportunity to Influence Legislative Priorities

A majority (72%) of female MPs agreed that policies, protocols and the structure of Parliament allow each member an equal opportunity to influence what is placed on the list of legislative priorities (see Figure 5). The fact that a majority of male MPs (66·6%) also agreed with this idea is an indication of a widespread adoption of human rights rhetoric and an internalisation of equal opportunity discourse. Moreover, many female MPs spoke highly of Affirmative Action as a policy that has allowed them more influence. They feel that they are now able to participate in any position in which they are interested, especially in chairing committees.

Figure 5. Equal opportunity.

There is no doubt that Affirmative Action policies mandated by the Constitution have normalised the presence of women politicians. Several female MPs cited the importance of Affirmative Action in providing them with the ability to be influential in policymaking.

The Affirmative Action in the constitution makes us very proud in such a way that … whenever we are getting any appointments, we normally ask, where is our 30% in that party? So we have the law, which is very supportive. (Female MP)

MPs Success in Advancing Policy Priorities

In response to a question regarding their ability to advance policy priorities in the previous year, 56% of the female MPs and 73% of their male counterparts responded ‘yes’, that they were successful (see Figure 6). Figure 7 lists factors believed to contribute to success and failure in advancing policy priorities.

Figure 6. Policy priorities and success.

Figure 7. Factors contributing to or hindering success.

Reponses to these questions suggest that there are persistent elements of the gendered structures of Parliament that disadvantage female MPs. Parliament, as an organisation, remains a workplace that is traditionally structured based on the paradigm of families having a sole male breadwinner. The work structure, operations and work hours overlook the realities of the lives of female Parliament members who struggle with balancing family and care-giving responsibilities – for which they are solely responsible – with their responsibilities as members of Parliament. Working conditions have not kept up with the needs of women. This hinders women's full participation and impedes their effectiveness. Many female MPs lamented the fact that ‘Parliament has not yet made Parliament interesting and attractive for women who are mothers’. The gendered division of labour and patriarchal norms disproportionately disadvantage women with respect to their ability to access networks on a similar scale to men and subject them to a constant struggle for work-life balance. This struggle most often results in less time spent doing their Parliamentary work, which limits their ability to gather and analyse information to make informed decisions. Female legislators stated that because of the difficulty they face in attempting to balance work and family demands, women end up adopting the views of others, rather than doing their own independent research.

Female MPs in most cases retire from legislative work and head home immediately. This denies them opportunities for networking and information gathering that their male counterparts obtain from evening gatherings in bars and other social venues. (Female MP)

It's hectic, in a way … You divide it (time) between family, constituency, and the office, Parliament; so it is quite challenging. (Female MP)

Parliament is a male institution, not only dominated, but it is a male structured institution even in terms of time for the work. They don't consider that you are a mother [and that] you have to go home. (Female MP)

Performance on the Chamber Floor

Wang's (Reference Wang2014) study of MPs’ speech in the Ugandan Parliament found no gender differences in overall speech activity. Female MPs in leadership positions speak significantly more than any other group and there is no difference between speech activity of Women Representatives and that of their counterparts.

Analysis of the discourse on pro-women bills in Parliament revealed that most female representatives are powerful contributors in Parliament, leading the effort to raise issues of concern for women. Many see their role clearly as advocates for women and are not apprehensive about using a wide range of strategies. Two cases of Parliamentary debates demonstrate female Parliament members’ agency and, by implication, acceptance of women's agency in Parliament.

The first case occurred in September 2013, when the Vice Chairperson of UWOPA presented a motion for a Parliamentary Resolution on the Compensation and Settlement of the Women Affected by the Proposed Government's Plans for the Construction of the Oil Refinery in Buseruka, Hoima District. The motion addressed the issue of women being excluded from the compensation process for selling land, deprived of their source of income as primary users of the land for family sustenance, and intimidated and barred from the decision-making process by agencies hired by the Ministry of Energy. In defence of their positions, several women and their male allies invoked values of equity and fairness in the distribution of compensation among women and men for land acquired for construction of the oil refinery, appealed to the rights of children, and emphasised the value of motherhood and the role of mothers as caretakers and providers. They underscored the need for the Gender Equity Certificate to ensure gender-sensitive resolutions; and appealed to the (female) Speaker's gender consciousness and her leadership as a woman. They pointed out that Affirmative Action was created to increase the number of women MPs who can bring in a woman's perspective and ‘speak for women’. They also engaged the opposition forcefully, and cited the constitution as providing equal rights and equal treatment for women (Parliament Proceedings 26.9.2013).

The second case involved a long debate on the Marriage and Divorce bill, which spanned several sessions and provides another window into gender relations, the constraints and barriers women face, and female MPs’ agency. The Marriage and Divorce Bill challenges property rights in cases involving the dissolution of marriage and cohabitation, and calls for making bride gifts (bride price) non-refundable. Women advocates for the bill and their male allies faced a wide range of challenges including a description of the bill as a law that would lead to ‘the commercialisation of marriage’, an increase of violence in the family, instability and discouragement of marriage, ‘the disappearance of families’, and ‘an impingement on the rights of the family’. Opponents framed the bill as ‘an exploitation of men by greedy women’. In challenging the bill, Representatives used phrases such as ‘controversial’, ‘mechanical’, ‘emotive’, ‘unacceptable’, ‘associated with the dotcom men and women and not the traditional women we have had in the past’, and a law that will have ‘very serious repercussions in the village’. Opponents also appealed to the identity of the country as a ‘Christian’ nation and the moral obligation to refrain from enabling cohabitation and divorce (Parliament Proceedings 7.2.2012).

Women advocates for the Bill addressed these challenges through a variety of strategies including clarifying the intent of the bill, refuting misleading claims and misunderstandings about the Bill's intent, and emphasising the gender neutrality of the bill. They confronted women who had made gender-insensitive statements, and argued that children would be the beneficiaries of the bill. They also argued for fairness to women whose household labour justifies property sharing, and called for a balance between modernity and religious traditions. They reminded members of the slippery slope they would create once religious arguments enter into Parliamentary debates.

In addition to the debates on these two bills, female members of Parliament led the effort to bring forward issues that affect women disproportionately. On 7 February 2012, for example, the Chairperson of UWOPA demanded that Parliament address the failure to implement the Domestic Violence laws that were passed in 2009, and called for the development of regulations to implement the Act. She emphasised the need to inform and train members of the local council system, set up special units of the police to deal with domestic violence, strengthen the system at health centres to assist victims of domestic violence, and train magistrates, judicial officers and legal personnel to adjudicate. Her direct demands were made to the Ministry of Gender to ‘immediately’ develop and issue the regulations for the implementation of the Domestic Violence Act, set up social services for the survivors, install toll-free phone numbers for police and medical emergencies, establish social and rehabilitation centres, and develop and disseminate a training guide for different public officials dealing with survivors. Several female representatives voiced their support for demonstrations of Parliament against domestic violence on a quarterly basis.

Another exchange provides additional insights into gender dynamics among members. This exchange occurred when members discussed the report examining progress made by local governments with respect to the promotion of gender equity and equal opportunities.

Gender mainstreaming is not anywhere in those local councils … So, if we are going to help this country on issues of gender mainstreaming, this Ninth Parliament should not finish its term without passing a law on gender equity certificate. If we do so, we shall have helped this country. (Female MP, Parliament Proceedings, 5.11.2013)

The Ministry of Gender, Labor, and Social Development is always considered last. When you go to the districts, the (budget) line Department of Community Services also comes last to the extent that, sometimes, it is given zero budget. (Male MP, Parliament Proceedings, 5.11.2013)

The 8th Parliament successfully passed a number of women-centred bills including the Equal Opportunity Commission Act of 2006, the Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation Act of 2009, the Prevention of Trafficking in Persons in 2009, and the Domestic Violence Act of 2010. This trend was halted in the 9th Parliament when the Marriage and Divorce Bill was ‘shelved’ by the Speaker after widespread popular opposition from within and outside Parliament. In both Parliaments, female MPs demonstrated an understanding of their legislative work and their role as Parliament members and spokespersons for their women constituents.

MEASURING CHANGE

The study affirms the hybrid nature of culture and its ability to transform and be transformed by formal institutions. We use Gerson & Peiss's (Reference Gerson and Peiss1985) conceptual framework to explain how and why change in the gender landscape is taking place. The framework is valuable in the analysis of change in gender relations. Affirmative action policies that brought women into an exclusive male space triggered a redefinition of the boundaries of male and female spaces. These policies disrupted the physical and psychological boundaries. The infiltration of women into a male space did not, however, guarantee change in gender interactions and relations. In fact, as we have seen from earlier work of Tamale (Reference Tamale2000), attempts were made successfully to keep women in their place through a variety of means including sexual harassment. Once women crossed the physical boundaries, they were able to organise under the auspices of UWOPA. The networks that women created in Parliament through UWOPA provided critical strategic support, influence and access to resources that women harnessed effectively at different points to further re-shape psychological boundaries. As Gerson & Peiss (Reference Gerson and Peiss1985) argue, changes take place at three dimensions of boundaries: negotiations, domination and consciousness. When change happens in one dimension, it results in changes in the other two dimensions. Women's agency, reflected in their use of negotiations were propelled by UWOPA's effective organisation, and enabled women to cross more boundaries – ideologically and psychologically. At the same time, women demonstrated increased awareness of their rights and responsibilities. They bargained for increased space, privileges, resources and opportunities for themselves and for their female constituents. In the process, they were challenging and re-drawing the contours of male dominance in Parliament. Women's ascent to leadership within Parliament represented another psychological breakthrough. Their consciousness and that of some males were changing in the process. Their perception of their own skills and efficacy as well as the perception of their male colleagues of the skills female MPs bring to Parliament were changing. Changes arising from negotiations and increased consciousness led to shifting in the boundaries of male dominance. Feeling respected and having a sense of empowerment and self-efficacy, however small, is sufficiently significant evidence of the shifting of boundaries in gender relations.

While we recognise that social desirability bias may be a factor that could influence how female and male MPs wish to be perceived or represent themselves in surveys and interviews, it could not explain the changing behaviour of female MPs on the floor of Parliament. They clearly expressed an awareness of their own rights and responsibilities and a voice that is amplified by a newfound sense of empowerment. It is a far cry from earlier accounts narrated by Tamale's (Reference Tamale2000) of female MP interviewees who conveyed a sense of acceptance and resignation, acknowledging that somehow it is normal for men to engage in sexual harassment of their female colleagues in Parliament.

Therefore, it seems most reasonable that the spark of change was lit by Affirmative Action policies. Having a critical mass of women in Parliament cannot, however, be credited alone for the changing gender schema. UWOPA's organising propelled women's agency and enabled boundary crossing that was afforded to them through the quota, which then allowed them to enact further redefinition and redrawing of boundaries. Through negotiations, they carved out a greater space for themselves. Thus, a new picture emerges of female MPs redrawing boundaries of gender relations. Women are increasingly aware of their rights and responsibilities; there is a heightened gender awareness and female MPs conduct vibrant negotiations on behalf of themselves and their female constituents. Moreover, there is an overall readjustment to opportunities to balance the scales of power.

CONCLUSION

This study reveals the unintended consequences of Affirmative Action policies that were designed by President Museveni to merely capture the female vote and loyalties (Tamale Reference Tamale2000; Goetz Reference Goetz2002). Although Affirmative Action policies were never meant to alter gender relations, the winds of change are sweeping through the main governing body of Uganda. Similar to what Wyrod (Reference Wyrod2008) observed in Kampala's urban society, a new conceptualisation of gender relations has emerged within the walls of the most formidable bastion of male power – the Ugandan Parliament. Women (and men) are feeling a new sense of empowerment, a sense of respect for women's presence, agency and leadership. Female MPs and their male allies are successfully leveraging their individual and collective agency to advance gender equity legislation, and delve into the uncharted waters of gender equality. They have succeeded in gendering the policy agenda, its process and its outcomes through employing a range of political strategies, including the introduction of bills and motions within Parliament, effectively debating the issues on the chamber floor and building cross-gender and cross-party alliances. Debates on the Marriage and Divorce bill reveal that the Ugandan Parliament as an institution is, for the first time, entering into taboo spaces that were previously uncontestable, such as the sharing of marital property and bride price. The ability to place these issues on the decision-making table would have been inconceivable a decade ago. It is a feminist transgressive action that goes far beyond gender consciousness; it is a direct challenge to the traditional concept of uncontested male control over resources and an acknowledgement of the value of women's unpaid household work. Moreover, it provides a basis for women's economic independence by loosening the grip of poverty. Perhaps most interesting, one cannot deny that the simple act of debating these issues is in itself unprecedented, particularly considering the patriarchal context in which it is conceived.

While the quota system was the initial trigger that set the wheels of change in motion, the development we see today in gender relations within the Ugandan Parliament would not have occurred without other enabling factors. Women's agency must be credited for facilitating change. Empowered by the strengths of their numbers, female MPs have been successful in legitimising their presence, challenging the male monopoly over institutional power, destabilising prevailing notions of male authority and carving out new realities in Parliament. Female MPs were also able to work across party lines through the Ugandan Women's Parliamentary Association, and to mobilise a large number of male allies in Parliament to vote positively on women-friendly bills and to join UWOPA. In addition, they were able to work effectively with civil society organisations.

Female MPs also effectively led debates in Parliament. They referenced universal human rights laws and conventions and the Ugandan Constitution to challenge regressive norms and reconcile traditional and religious values with the values of gender equity. Female MPs were able to harness the global, regional and local human rights rhetoric, which became an inescapable reality and mainstreamed gender equity discourses. These discourses were further promoted and enabled by the international donor community (Wang Reference Wang2013).

Notwithstanding the positive changes in gender relations and women's sense of empowerment within Parliament, there are still elements of continuity with the past. Traditional values remain intact with respect to the gendered household division of labour. Female MPs still face a disproportionate challenge in the area of work-life balance. They struggle to balance their traditional responsibilities as wives and mothers with their Parliamentary duties. Women continue to face sexual harassment (even if considered isolated and rare), unfair emphasis on their appearances, and double standards in judging their behaviour. Change is indeed an incremental process. These findings are further evidence of the complex and fluid nature of culture. They show that culture is a contested space that is capable of transformation as it interacts with institutional structures (Wyrod Reference Wyrod2008). Will the trend continue? Will we continue to witness the erosion of the structures of gender inequality? To what extent can female MPs’ agency within the walls of Parliament succeed in infiltrating the untouchable quarters of the private sphere? History is on women's side.