Between 1949 and 2021, the aggregate number of political science master’s (MA) degrees awarded in the United States was more than the aggregate number of political science doctor of philosophy (PhD) degrees awarded; specifically, 119,008 MA degrees versus 36,869 PhDs.Footnote 1 Despite the fact that more than three times as many MA degrees have been awarded, most of the focus on graduate programs in political science reflects the PhD degree. For example, a report issued by the American Political Science Association (APSA) 2002 Task Force on Graduate Education mentions MA degrees only in passing. It suggested that “APSA publicize how undergraduates can use its graduate student website to link to departments offering PhD programs and that the website add links to master’s programs” (Beltran et al. Reference Beltran, Cohen, Collier, Goldenberg, Keohane, Monroe, Wallerstein, Achen and Smith2005). Almost 20 years later, this suggestion remains unfollowed.

This lack of focus on MA degree programs in political science is at odds with broader trends in graduate education. MA degree programs have evolved to meet the effects of globalization, shifting demographics, market demands, and technological advances while also remaining “a pivotal degree that bridges the baccalaureate, the doctorate, and the workplace, and [has] the capacity to continually evolve as a highly adaptable and affordable credential” (Glazer-Raymo Reference Glazer-Raymo2005). Given the lack of research on MA degrees in political science, we questioned whether political science MA degree programs have similarly evolved to meet student expectations and provide training for nonacademic careers.

This article focuses specifically on terminal MA degree programs in political science. We define a terminal MA degree program as one in which the goal of an MA degree is achieved after the “successful completion of a program generally requiring one or two years of full-time college-level study beyond the bachelor’s degree.”Footnote 2 The intent of our research is to fill a gap in the literature on graduate programs in political science by first providing information about MA degree programs in political science and then evaluating the extent to which these programs reflect broader changes in education at the MA-degree level. In addition to gathering information on demographic and other characteristics of political science MA students, we collected data from 127 terminal MA degree programs in the United States to describe these graduate programs across dimensions that reflect curricula, culminating-project requirements, and graduate student learning outcomes (SLOs). We also surveyed the graduate coordinators and directors from terminal MA degree programs to gather additional information about program goals and SLOs (De Maio and Macias Reference De Maio and Macias2024). This research has important normative implications for a reconceptualization of MA degree programs in political science. Specifically, our research suggests that curricular changes emphasizing skills development and career preparedness are aligned with the broader trends in graduate education at the MA-degree level and should be encouraged. Thus, we offer our suggestions toward a best practices model for MA degree programs in the discipline of political science.

The intent of our research is to fill a gap in the literature on graduate programs in political science by first providing information about MA degree programs in political science and then evaluating the extent to which these programs reflect broader changes in education at the MA-degree level.

MASTER’S DEGREE PROGRAMS IN HIGHER EDUCATION

Across many academic disciplines, there has been an increased emphasis on the development of professional skills through the inclusion of experiential-learning programs and internships. This focus is reflected in changes in teaching methodologies from traditional lecture-based approaches to more interactive, project-based, and student-centered learning with the goal of fostering critical-thinking and practical skills (Michael Reference Michael2006). Many of the changes are driven by employer demands and shifts to a knowledge-based economy that favors more educated and academically skilled workers (Wendler et al. Reference Wendler, Bridgeman, Cline, Millett, Rock, Bell and McAllister2010). Programs claim to produce graduates who are career ready, thereby bringing the university much closer to the corporate world (Briggs Reference Briggs2016). The MA degree has become an “entrepreneurial credential…that is more responsive to the marketplace than to traditional academic environments” (Association for the Study of Higher Education Report 2005).

With respect to political science, the inclusion of internships, practical training, and networking opportunities potentially may increase employment prospects. Most MA degree students do not go on to pursue PhDs. Therefore, if an MA degree truly is the new bachelor’s degree (Anderson Reference Anderson2013; Pappano Reference Pappano2011) for young workers who want to distinguish themselves in a competitive job market, it makes sense to ensure that they have the professional skills and are career ready by the end of their MA degree program.

Some disciplines have recognized that their students are seeking career-focused mentorship and training in finding jobs and networking (Cronin and Hawvermale Reference Cronin and Hawvermale2021). This may result in a mismatch between what graduate programs are teaching and the nonacademic work that most MA students go on to do (Price Reference Price2001). A growing literature notes the disconnect between traditional academic programs and applied programs that focus on mentoring and internships, encouraging departments to find ways to facilitate connection and collaboration with praxis-based teaching (Briody and Nolan Reference Briody, Nolan and Nolan2013; Nolan Reference Nolan1998; Trotter Reference Trotter1988). Examples are found in shifts from research-oriented programs to “taught master’s” that are focused on preparing students for nonacademic careers (Monk and Foote Reference Monk and Foote2015). These new MA degrees prioritize “equitable access, employability, and lifelong learning” (Monk and Foote Reference Monk and Foote2015, 473). Despite the emphasis on equitable access, enrollment patterns and completion rates differ across demographic groups. Although “the share of Black and (Latino/a/x) students enrolled in master’s programs has nearly doubled in 20 years, from 14% in 1996 to 25% in 2016” (Blagg Reference Blagg2018), completion rates for MA students tends to be lower than for PhD students. Baum and Steele (Reference Baum and Steele2017) found that “26% of those who began master’s degree programs left school without completing a degree compared with 12% to 14% of those in other types of programs,” with “students from higher income backgrounds more likely than others to enroll, more likely to complete their programs, and more likely to earn degrees that promise high value in the labor market.” With graduate programs increasingly being taught online and becoming more expensive (Blagg Reference Blagg2018), financing a graduate degree is more difficult for MA degree students. According to Wendler et al. (Reference Wendler, Bridgeman, Cline, Millett, Rock, Bell and McAllister2010, 36):

…there are differences in the types of financial support provided to master’s- versus doctoral-level students. Relatively small percentages of students enrolled in a master’s program are provided institutional support or assistantships. Instead, master’s students rely more on loans and employer support. For doctoral students, financial support is generally provided by or through the institution (assistantships, traineeships) or by the student’s employer.

This combination of lower completion rates in MA degree programs and more expensive loans required to help finance an MA degree potentially may outweigh the earning benefits of the MA degree and dissuade potential students from pursuing it.

Research suggests that MA education in the United States could be restructured to better prepare students for a career by teaching them key skills, including time management, writing and public speaking, information literacy, and teamwork (Monk and Foote Reference Monk and Foote2015). An example is found in the anthropology department at the University of Memphis, which uses the “Memphis Model,” a praxis-oriented mentorship program that connects current graduate students with the alumni network in their area (Feldman et al. Reference Feldman, Brondo, Hyland and Maclin2021). In the process of preparing current students for a career, the Memphis Model also establishes a deeply rooted alumni network because many of those students return to train the next generation.

To meet the needs of students interested in pursuing further graduate study as well as those with more professionally focused interests, some social science programs offer two tracks: Plan A, which prepares them for PhD research; and Plan B, which prepares them for a nonacademic career (Monk and Foote Reference Monk and Foote2015). By allowing students to choose a specific track, programs may be better positioned to meet their needs. In the geography department at Western Illinois University, for example, students can complete an “applied project that provides practical experience in design and solution of a real-world problem.”Footnote 3 New Mexico State University offers a similar applied nonthesis option that connects students with a sponsor to complete a “residency project.”Footnote 4 Culminating projects such as these that allow students to gain work experience and acquire professional skills may prepare them to be more competitive in the nonacademic job market.

If a critical purpose of an MA degree is to prepare a student for a career outside of academic research, we then ask: “How much of that which programs are focusing on in political science is related to professional preparation?” To better understand the motivations of students seeking an MA degree in political science and the type of training they receive, the following section is an analysis of terminal political science MA degree programs.

MASTER’S DEGREE PROGRAMS IN POLITICAL SCIENCE IN THE UNITED STATES

The literature on MA degree programs in general discusses differences in terms of demographic factors, the financing of graduate education, and the motivations of students who seek a terminal MA degree. This section presents data on demographic characteristics and funding of graduate students in political science at the MA- and PhD-degree levels from the 2021 Survey of Graduate Students and Postdoctorates in Science and Engineering (GSS).Footnote 5 Additional information about motivations for study at the MA-degree level in political science from the 2021 National Survey of College Graduates (NSCG)Footnote 6 is included to determine the extent to which the interests of political science MA degree students reflect evidence from the broader literature. To determine whether programs offering the MA degree in political science reflect broader changes in education at the MA-degree level, we used the College Navigator search engineFootnote 7 on the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) websiteFootnote 8 to identify 233 political science departments that offer an MA degree. We eliminated programs that grant MA degrees only as part of a PhD program because their goal is not the MA degree but rather the PhD degree. We also excluded MA degree programs in public administration, given their classification as “professional” programs.Footnote 9 Based on these parameters, what remained was a dataset of 127 terminal MA degree programs in political science.Footnote 10 Finally, to gather more information about programmatic changes and additional characteristics of the MA degree programs in political science, we designed an online survey using SurveyMonkey and invited MA degree program coordinators and directors to respond.Footnote 11

The racial and ethnic composition of graduate students at the MA- and PhD-degree levels of political science in 2021 (table 1) reflects higher percentages of Latino/a/x and Black graduate students in political science at the MA-degree level (15.40% and 9.30%, respectively) compared to the PhD-degree level (6.30% and 4.70%, respectively). There also is a higher percentage of “non-Hispanic” white graduate students at the MA- degree level (52.70%) versus the PhD-degree level (45.33%). However, the most surprising difference in demographic categories was for “Foreign Nationals Holding Temporary Visas, Regardless of Ethnicity or Race”: 32.70% at the PhD-degree level compared to 10.50% at the MA-degree level.

Table 1 Demographic Characteristics and Sources of Funding for Graduate Students in Political Science, 2021

Source: National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, Graduate Students and Post-Doctorates in Science and Engineering Survey, 2021 (https://ncsesdata.nsf.gov/builder/gss).

With respect to gender, the percentages of men (53.50%) and women (46.50%) at the MA-degree level of study in political science are similar to those at the PhD-degree level (55.40% and 44.60%, respectively). Differences between MA and PhD degree programs were apparent in a comparison of funding sources for graduate study. Whereas a majority (73.14%) of graduate students at the doctoral level in political science received institutional support for their education, only 17.25% of MA students received such support. The much higher level of institutional support for doctoral students may be connected to the lower percentage of PhD students (9.45%) who reported self-support (including loans and family sources) compared to the percentage of MA students who reported self-support of their education (31.34%). Notably, for almost half of the MA students (48.41%), sources of support were not collected by the institution; the percentage of unreported support for PhD students was only 11.74%.

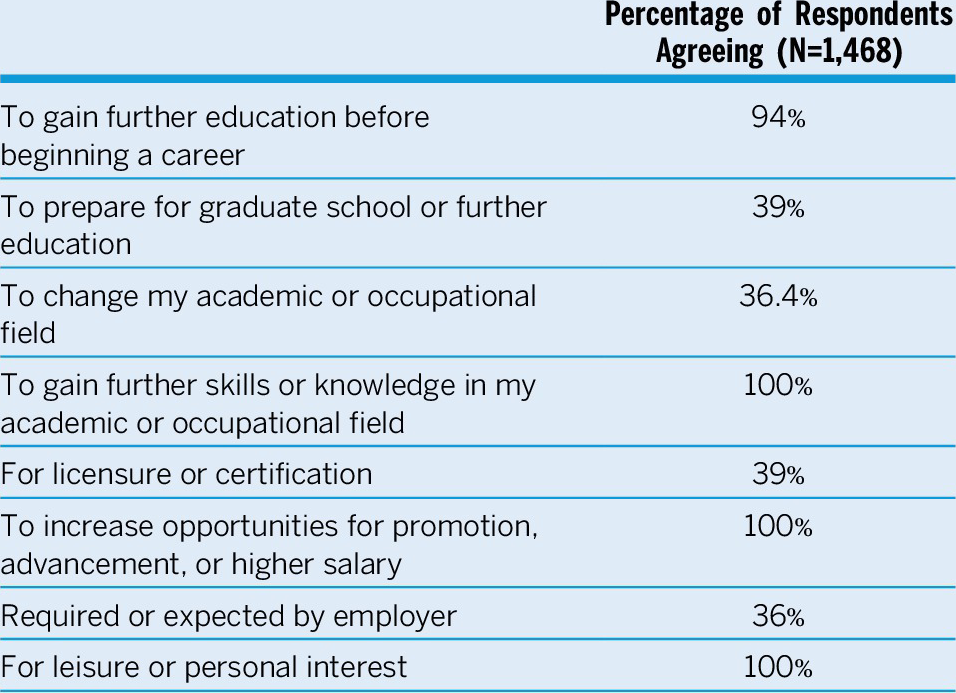

Given the lower levels of institutional support and higher levels of self-support necessary for political science graduate students in MA degree programs, their motivations for seeking an MA degree are worth investigating. Fortunately, the NSCG provides data on college graduates with at least a bachelor’s degree in terms of post-baccalaureate activity, including graduate study. The 2021 survey asked respondents if they were enrolled in a degree program during the survey period, as well as the type of degree, field of study, and motivation for enrollment. Table 2 presents students who were seeking a political science MA degree in 2021 and their level of agreement regarding specific motivations for graduate study. Of these respondents, 100% indicated that their motivations for graduate enrollment were “to gain further skills or knowledge in my academic or occupational field”; “to increase opportunities for promotion, advancement, or higher salary”; and “for leisure or personal interest.” Among these responses, two were specifically employment related: 94% indicated “to gain further education before beginning a career.” Notably, only 39% indicated “to prepare for graduate school or further education.”

Table 2 “For Which of the Following Reasons Were You Taking Courses or Enrolled…” (Enrolled in an MA Degree Program in Political Science, 2021)

Source: National Survey of College Graduates, 2021 (https://ncsesdata.nsf.gov/builder/nscg).

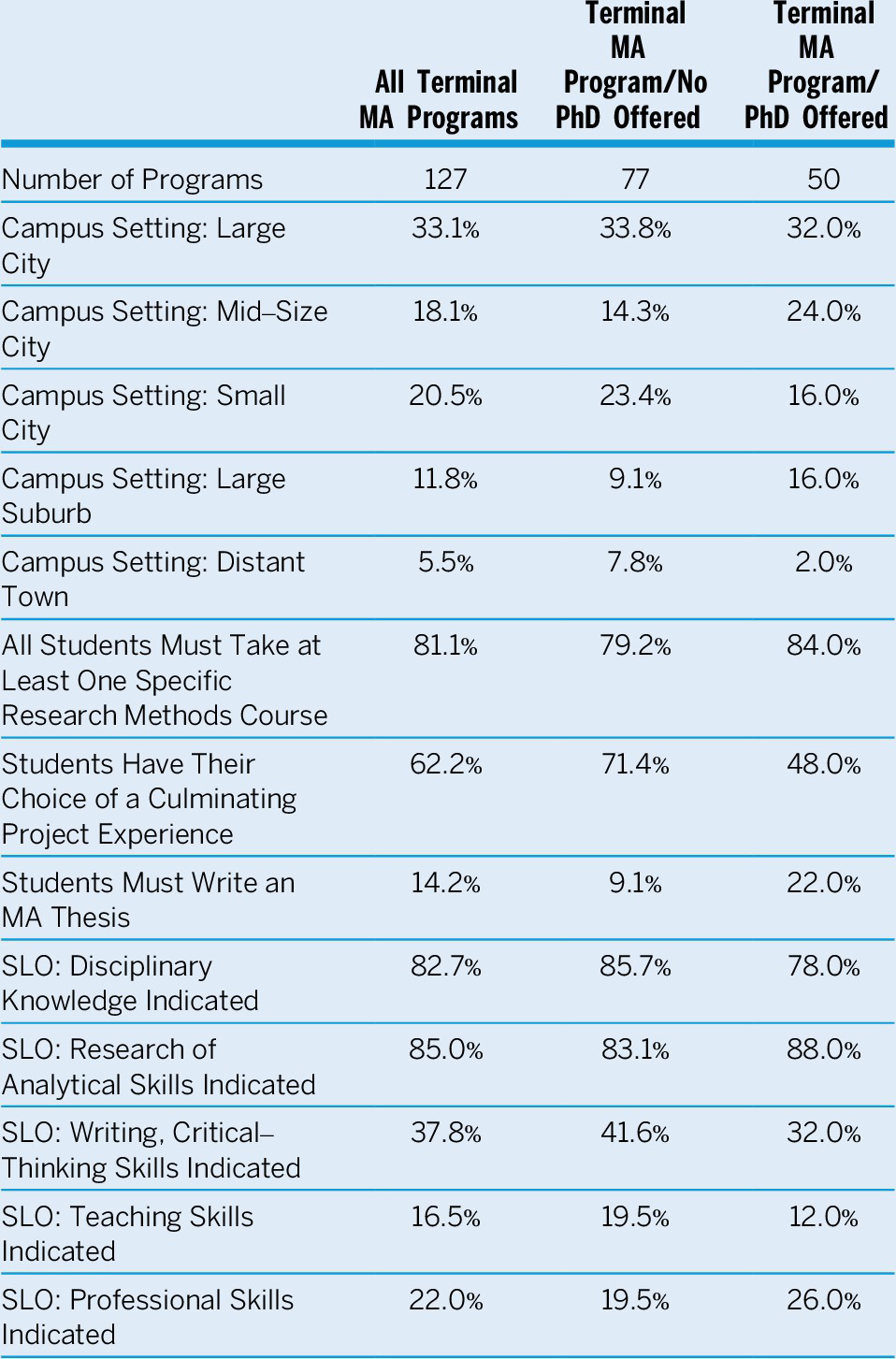

To gather information about their terminal MA degree program, we visited the website for each political science department in our dataset of 127 programs. This information included (1) whether the program also offered a PhD in political science; (2) the expected time for attainment of the MA degree; (3) specific courses required of all graduate students in the MA degree program; (4) whether a culminating experience was expected of all MA students; (5) what type of culminating experience was expected; and (6) specific SLOs expected for all MA students.Footnote 12 Results from this analysis are listed in table 3.

Table 3 Characteristics of Terminal MA Degree Programs in Political Science, 2022

Source: De Maio and Macias Reference De Maio and Macias2024.

Most of the MA degree programs (71.7%) in political science were located in cities of diverse sizes, and most of them (78.7%) were at four-year public universities with an average student population size of 26,423. More than half of the programs (60.6%) were in departments that do not offer PhD degrees. Most of the programs (90.6%) were two years in length. A majority of programs (81.1%) required students to take at least one specific research methods course, with less than half of those (48.0%) requiring a non-research methods course. A slightly higher percentage of MA degree programs required a research methods course if they were in a department that offers a PhD in political science (84.0%) compared to a department that does not (79.2%). Regarding culminating experience requirements, we found that 62.2% of programs offered students a choice of culminating experience, typically either a written project (e.g., thesis or paper) or an examination. A written thesis was required in 14.2% of all degree programs; 5.5% required a combination of these options and 3.1% did not require a culminating experience. Students in an MA degree program in a department that offered a PhD program were less likely to have a choice in their culminating experience (48.0%), compared to those in a department that does not (71.4%). Conversely, MA students in a department in which a PhD was offered were more likely to have a thesis requirement (22.0%) than MA students who were not in a PhD-granting department (9.1%).

SLOs from the program websites were collected to determine the types of outcomes that are expected for MA degree programs in political science. Coding of SLOs and mission statements resulted in five general categories of outcomes: (1) disciplinary knowledge outcomes (e.g., “demonstrate understanding of the core questions and basic literatures in at least one subfield of political science”); (2) research or analytical skills (e.g., “show a fluency in reading quantitative research findings and the ability to undertake basic analysis using quantitative tools”); (3) communication (written and/or oral) and critical-thinking skills (e.g., “demonstrate mastery of writing”); (4) teaching skills (e.g., “the program also provides a well-rounded substantive curriculum for secondary schoolteachers seeking higher degrees and for teachers in community colleges”); and (5) professional skills (e.g., “professional development through internship experience”). Each MA degree program was coded for the presence or absence of these SLOs. Overall, we found that research or analytical skills were referenced most often (85.0%), followed by disciplinary knowledge (82.7%), communication and critical-thinking skills (37.8%), professional skills (22.0%), and teaching skills (16.5%). The major difference between terminal MA degree programs in which a PhD was offered and those that did not was regarding the critical-thinking SLO. Departments that offered both a terminal MA degree and a PhD degree were less likely to reference this SLO (32.0%) than those that only offered a terminal MA degree (41.6%). It is interesting that programs that offered a PhD as well as the terminal MA degree in political science were slightly more likely to reference the professional-skills SLO (26.0%) than those that offered only a terminal MA degree (19.5%).

Our analysis of MA degree program websites provided answers to our questions about the content and structure of terminal MA degree programs in political science. Given the predominance of disciplinary and research emphases in these programs, we asked whether this was an artifact of programs that have not been updated to reflect the changing emphases of MA degree programs. Our survey was designed to answer some of these questions.

We received a total of 35 responses,Footnote 13 which reflects a response rate of 27.6%. The survey asked 23 questions, including the following:

-

• whether a PhD in political science also was offered

-

• the primary purpose of the MA degree program

-

• expected time to complete the MA degree

-

• whether there was a culminating experience expected of students

-

• when the MA degree program curricula was last changed

-

• whether an internship or professional requirement was part of the MA degree program

-

• whether the program worked in conjunction with the university’s career center

-

• whether the program tracked students after they completed the program.

After verifying that survey respondents were in programs in the NCES dataset, we compared sample institutional characteristics with the NCES dataset characteristics. Compared to the NCES dataset of 127 programs, 71.4% of respondents were from programs located in cities (compared to 71.7% in the NCES dataset), with 94.3% of the respondents representing four-year public universities (compared to 78.7% in the NCES dataset). Similar to the NCES dataset (60.1%), 60.0% of the survey respondents reflected programs that do not offer a PhD in political science.

A majority of respondents (71.4%) indicated that the approximate length of time a student needed to complete all of the required components to earn a terminal MA degree was four semesters: 80.0% of the graduate coordinators and directors reported that more than half of their students were able to complete program requirements in four or fewer semesters. When asked what the purpose of their MA degree program was, 41.2% of graduate coordinators and directors responded “to prepare students for nonacademic professions such as public or government service,” followed by 17.6% who selected “to prepare students for further graduate study in political science”; 14.7% who chose “to prepare students to teach or conduct research.” More than a quarter (26.5%) of respondents indicated “all of the above” and 2.9% chose “other” as the main purpose of the MA degree program in political science. Given that more graduate coordinators and directors chose “to prepare students for nonacademic professions such as public or government service” as the main purpose of their MA degree program, we were surprised to find that only 5.7% indicated that professional training or an internship was required. Only 30.3% of the graduate coordinators and directors reported working with their university’s career services program or office, and only 20.0% reported that they tracked their students after completing the program.

Regarding curricula, 60.0% of graduate coordinators reported that students had a choice of culminating-experience options, 17.1% indicated a paper or portfolio, 14.3% indicated a thesis, 5.7% reported a combination of requirements, and 2.9% indicated a comprehensive examination. Although 71.5% reported that changes to the curriculum had taken place in the past five years, only 22.9% reported that they involved a switch between a traditional thesis-based MA degree and a project-based or professional-experience–based MA degree. When asked how many MA students went on to pursue a PhD, 45.7% indicated 10.0% or less, 25.7% indicated 20.0% to 50.0%, 8.5% indicated 50.0%, and 20.0% indicated either that they did not know or did not answer.

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

Despite shifts in MA degree programs and the motivations of students seeking a terminal MA degree in political science, we found that most of the curricula seems to focus on preparing students for further graduate study rather than the development of critical-thinking or professional skills. We found that there is a disconnect between what MA degree programs acknowledge they should be providing students and how students are trained. Graduate program coordinators and directors recognize that they need to prepare students for jobs outside of academia; however, the emphasis remains on research and scholarship. We observed this in programs that are more likely to require research methods courses than other types of courses, the small percentage of culminating experiences involving internships or professional skills, and SLOs and mission statements that are more likely to reference disciplinary and methods outcomes compared to professional-skills outcomes. Given the small percentage of graduate coordinators and directors who reported working with their campus career centers, the lower percentage of references to professional skills in SLOs and mission statements, and the lack of required internships or other types of career training, MA degree programs in political science do not seem to reflect broader changes in graduate education at the MA-degree level. This is concerning, given the motivations of students seeking an MA degree in political science and the probability that many of them pursue the degree without institutional support. Therefore, we must ask: “How can terminal MA degree programs in political science be improved to better meet the needs of students pursuing this degree?” Table 4 summarizes our best-practices suggestions for terminal MA degree programs in political science.

Despite shifts in MA degree programs and the motivations of students seeking a terminal MA degree in political science, we found that most of the curricula seems to focus on preparing students for further graduate study rather than the development of critical-thinking or professional skills.

Table 4 Best-Practices Suggestions for Terminal MA Degree Programs in Political Science

Source: De Maio and Macias Reference De Maio and Macias2024.

MA degree programs in political science do not seem to reflect broader changes in graduate education at the MA-degree level. This is concerning, given the motivations of students seeking an MA degree in political science and the probability that many students pursue the degree without institutional support.

BEST PRACTICES FOR TERMINAL MASTER’S DEGREE PROGRAMS IN POLITICAL SCIENCE

To better align terminal MA degree programs in political science with student and job-market demands, changes must be made. Indeed, Ishiyama (Reference Ishiyama2022) recently wrote about “the rising demand from various higher education ‘stakeholders’ that there be a greater emphasis on employable skills at the undergraduate level.” This is equally applicable to the MA degree. Our findings suggest that such an emphasis is not present. Although the question of resources may be a factor, not all change requires a significant reallocation. Experiential-learning courses and internships, integrating practitioners into the classroom, and using existing resources at university career centers are examples of change. Training MA students for further graduate study leading toward a PhD degree can coexist with training students how to use their knowledge for jobs outside of academia. MA students need to have transferrable skills that will prepare them for nonacademic careers.

To meet the interests of students who seek an MA degree to develop their career prospects and skills, best practices at the program level should include a reexamination of SLOs to incorporate professional skills. Professional skills can be developed through the incorporation of internships into the MA-degree curriculum as part of a separate “nonacademic” track. A professional-skills–oriented culminating experience then would be important evidence for future employers that professional skills not only were developed but also mastered as part of the MA degree. Greater utilization of existing campus career-center resources can help to accomplish this. Moreover, better tracking of MA degree program graduates could be useful in understanding the types of nonacademic careers that they enter into as well as provide a potential resource for programs through an alumni career network. The tracking of program alumni also could provide information on how well programs are delivering on their professional-skills SLOs.

Our suggestions for program-level best practices resulted from our analysis of MA degree program websites and from our survey of graduate program coordinators and directors. There remains, however, a lack of information about terminal MA degree programs in political science, which prompts our inclusion of best-practices suggestions for the discipline. We recommend a list of all institutions offering MA degrees or a link to the College Navigator website on the APSA website. Future APSA task force reports of graduate education should explore issues in graduate-level education at the MA-degree level with the same energy and commitment as for PhD programs. We argue that the lack of such an effort in the discipline is a glaring weakness, given that terminal MA degrees are earned by more graduate students and offered by more departments in political science than PhD programs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Bentley McVicker for his research assistance and to Dean Yan Searcy for his support of the project.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FZK6MW.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.