1. Introduction

We are embarking now on a change of direction that has been long overdue in the UK economy… and that is the direction in which this country is going now—towards a high wage, high skill, high productivity—and yes, thereby low tax economy—that is what the people of this country need and deserve, in which everyone can take pride in their work and in the quality of their work. And yes, it will take time. And yes it will sometimes be difficult, but that was the change that people voted for in 2016 and that was the change they voted for again powerfully in 2019 and to deliver that change we will get on with our job of uniting and levelling up across the UK, the greatest project that any government can embark on.

Boris Johnson Speech to Conservative Party Conference 6th October 2021

The Conservative Party Conference held in Manchester in early October 2021 offered two defining themes—‘Levelling Up’ and the ‘transition to a high wage, high skill, high productivity economy’—of a new economic model that, according to the then Prime Minister, people voted for in 2016 (at the EU Referendum) and 2019 (the General Election where the Conservatives won with an 80-seat majority). These priorities demonstrate two important truths: first, that the UK suffers from significant regional and local inequalities and second, that improving productivity lies at the heart of any mission to improve wages and strengthen the economy.

This chapter considers how the configuration and powers of local and national institutions relate to these objectives—and whether England’s governance arrangements, particularly at the sub-national level, support our ability and capacity to meet them. The paper argues that understanding the significance of institutions and governance to improving productivity and tackling regional inequality is a priority. We argue that the decisions ministers make about local and national institutions will be critical in the medium and longer term.

There is widespread consensus between economists, political scientists and policymakers that institutions are an important part of tackling both problems of widespread low productivity and with large regional differences (Coyle, Reference Coyle2020; McCann, Reference McCann2019). However, there is further value in understanding how different institutions work, what they are tasked to do and how they relate to others also involved in pursuing these objectives. As Coyle (Reference Coyle2020) says, ‘the challenge for researchers and policymakers is to understand—in each specific context—exactly what coordination is needed to increase productivity, and what actions (and by whom) can achieve this’.

The UK’s track record—and particularly that of England—over recent decades does not bode particularly well for tackling spatial inequality and low productivity. The British state is overly centralised—especially in England—compared to other countries (Pabst and Westwood, Reference Pabst and Westwood2021). It has weak local and regional institutions and a low regard for their role and importance. The institutional framework is fragmented and suffers from poor co-ordination between silos and different levels and is subject to instability and short termism—as well as extraordinary levels of policy churn (Norris and Adam, Reference Norris and Adam2017). It is telling that three policy areas important for improving productivity and reducing regional disparities are subject to the greatest instability: regional policy, industrial strategy and vocational education (Coyle and Muhtar, Reference Coyle and Muhtar2021; Keep et al., Reference Keep, Richmond and Silver2020; and Norris and Adam, Reference Norris and Adam2017).

1.1. What do we mean by institutions and why are they important?

To begin we must first define what we mean when we talk about institutions as definitions vary. US economist Ostrom (Reference Ostrom1986) pointed out that ‘little agreement exists on what the term “institution” means’. North (Reference North1992) describes institutions as ‘the rules of the game in a society’ and ‘humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction’. But like other economists, he distinguishes between ‘institutions’ and ‘organisations’ in the same way that in sport, ‘the rules are different from the teams or the players’. Both political scientists and policymakers tend to think of institutions and organisations as terms that are more interchangeable. In Why Nations Fail, Acemoglu and Robinson (Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012) see them as not only the ‘order’ and the ‘rules’ but also the institutions of government such as parliaments, central banks and departments that oversee enforcement, infrastructure or trade.

Wilkes (Reference Wilkes2020) points out the pitfalls: ‘in normal parlance, an institution is an organisation tasked with some function. For economists, it means something slightly different’. He explains that policy ‘must involve choices’ and that ‘politics is an inescapable part of it’. Nobel Laureate Stiglitz (Reference Stiglitz2019) agrees, ‘because the rules of the game and so many other aspects of our economy and society depend on the government, what the government does is vital; politics and economics cannot be separated’.

Taking ‘Levelling Up’—success will depend on the co-ordination of different layers of government from delivery departments in Whitehall to local and regional authorities across England. So how the Government chooses to define, configure and oversee their institutions, how they reform existing organisations and how they fund and direct them will matter—from ‘machinery of government’ changes to Whitehall Departments to the organisations on the receiving end of their policies. This is ‘multi-level governance’ (Rhodes, Reference Rhodes1997) or ‘multi-centric policymaking’ (Cairney, Reference Cairney2020) and it includes local and regional bodies and devolution (including policy, powers and resources) settlements across the four UK nations and within each country, to cities, towns and local communities too.

1.2. The centralisation of power: Westminster and Whitehall

Overcentralisation in both the UK political system and the UK economy remains a standout feature when comparing England to other countries. The UK, and in particular England, is an outlier in both regards (UK 2070 Commission, 2020). Despite devolution to three of the country’s four nations and to several city regions, Britain remains a unitary state that is one of the most centralised in the Western World, with fewest powers delegated to regions and communities (Haldane, Reference Haldane2021; Richards and Smith, Reference Richards and Smith2015).

The so-called ‘Westminster Model’ remains key to our understanding of government and its institutions (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012). It is the key set of institutions in the wider policy-making arena and the complexity of governance arrangements, broadly defined, within which UK policy operates. The ‘Westminster Model’ and the ‘Northcote-Trevelyan’ paradigm is still dominant (Richards and Smith, Reference Richards and Smith2015) and for now will set the terms of ‘Levelling Up’ as well as determine the powers, resources and makeup of local and regional institutions.

Politically, Westminster and Whitehall tend to centralise and hoard power even though many departments, with the notable exception of the ‘Imperial Treasury’, often lack power or influence over central decision-making or in the implementation of policy across the country. Moreover, successive British governments have a poor track record of effective cross-departmental co-ordination, as highlighted not just during the Covid-19 emergency but also in relation to the repeated failure to put in place a robust industrial policy (Coyle and Muhtar, Reference Coyle and Muhtar2021). New Whitehall departments have been created and renamed, and industrial strategy recalibrated with every new incumbent in No 10.

One of the most egregious examples of institutional or policy ‘short termism’ is regional policy which has been chopped and changed by successive governments with seemingly little effect on spatial inequalities. See figure 1 above for a summary of initiatives from a series of different governments aimed at stimulating local growth since the late 1980s (see Chapter 5 in Martin et al., Reference Martin, Gardiner, Pike, Sunley and Tyler2021 for a description of nine decades of regional policy). The gaps in economic performance between different regions and local areas during that time have not suffered from a lack of policy attention or intent. In the 1980s, the Conservative government set up ‘urban development corporations’ to improve land and property markets in urban areas, but this further entrenched disparities in suburban, rural and coastal areas and ultimately led to ‘the revenge of the places that do not matter’ (Rodriguez-Pose, Reference Rodriguez-Pose2018). New Labour tried to tackle regional inequalities by creating the National Strategy for Neighbourhood Renewal together with Regional Development Agencies (RDAs) across nine regions of England, alongside Regional Assemblies and City Mayors (both of which failed to take off outside London).

Figure 1. Regular changes in initiatives for local economic growth. Source: Adapted from National Audit Office (2019)

After 2010, the Coalition Government scrapped RDAs and replaced them with a series of Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs) which, a decade later, are now under a formal review from the current government. The Coalition Government also created a series of Mayoral Combined Authorities (CAs) (see Chart 1) with associated ‘devolution deals’ covering new powers and resources. But what has been missing is a clear, consistent approach to which powers of central government should be devolved alongside both resources and accountability. Furthermore, since 2019 there have been increasing geographical inconsistencies between programmes, powers and places leading to questions about how such arrangements might provide a sub-optimal basis for improving regional/local productivity gaps and/or ‘Levelling Up’.

Chart 1. (Colour online) Economic development institutions and arrangements in the Midlands (West and East).

Source: Research by authors and TPI Midlands Regional Productivity Forum

There is also institutional and policy churn at a national level. Since 1997 the Whitehall responsibility for local and regional government has been held by the Department for the Environment, Transport and the Regions, the Department for Communities and Local Government and now the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC). Alongside, the Business Department has also been chopped and changed, from Trade and Industry (DTI) to the Departments for Innovation, Universities and Skills and Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform then to Business, Innovation and Skills and now Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.

At local and regional levels, the past quarter of a century has also witnessed a shift from Training and Enterprise Councils (TECs) to RDAs and Learning and Skills Councils (LSCs) and then to LEPs and from Local Area Agreements and Multi-Area Agreements to CAs and now to ‘Levelling Up’ and to ‘Town’ or ‘County Deals’. There is very little institutional or policy stability within or between governments—even those of the same political party.

One feature of this is the lack of spatial consistency within and between government reforms. In England and Wales, there were initially 19 TECs created in 1990 looking after various economic and training schemes of the time. In the first term of the New Labour Government in England, these were replaced by nine RDAs and 47 Local LSCs. By 2010, both sets of organisations were abolished—partly in the name of waste—and replaced with 39 LEPs. Alongside there was the creation of several CAs (now nine in England) as well as the ‘Northern Powerhouse’ and ‘Midlands Engine’ brands. Very few follow the same geographical boundaries; instead, they represent often loosely or oddly defined areas that do not appear to follow a consistent or coherent geographical or spatial framework.

This takes us to a new wave of policy formation since 2018/2019 and the allocation of a range of relatively small-scale centrally administered pots of funding to institutions bidding into a series of policy competitions. These include the Local Growth and Towns Funds and more recently the ‘Levelling Up’, ‘High Street’ and ‘Community Ownership’ Funds.Footnote 1 These build on funding processes first created during the 1980s and also more recent funds such as ‘City Deals’.Footnote 2 However, it is clear that this approach is proliferating as a policy mechanism of choice and that the process itself creates problems, undermines local institutions and increases dependency on central government role for local economic strategies.

As Andy Haldane states, then Chair of the Industrial Strategy Council and Chief Economist at the Bank of England (and recently seconded to Cabinet Office to chair a ‘Levelling Up’ Taskforce announced during the Cabinet Reshuffle):

‘Centrally distributed funding pots are unlikely by themselves to be an effective or lasting solution to the ‘levelling up’ problem. The best laid plans are those laid locally and which build on a broad base of foundations including investment, education, skills and culture. That requires local institutions and requires them to have the holy trinity of powers, monies and people. The Plan for Growth contains too little to secure those local foundations and to develop those local institutions’.

Andy Haldane at Institute for Government seminar 23rd March 2021. Footnote 3

The UK does not just offer an example of centralisation in its systems of governance and the allocation of powers and resources. It is also ‘the most unbalanced and unequal country across the largest range of indicators’ (McCann, Reference McCann2019). According to Collier (Reference Collier2018), spatial inequalities have been driven by ‘a forty-year divergence in income, dignity, empowerment and finance between the metropolitan Southeast and other regions’. There is widespread consensus that significant gaps in productivity follow—within and between regions and subsequently, at a national level too, with evidence showing the UK’s governance system itself partly accounts for regional inequalities (Carrascal-Incera et al., Reference Carrascal-Incera, McCann, Ortega-Argiles and Rodriguez-Pose2020; McCann, Reference McCann2016) and that improving arrangements could ‘foster stronger and more inclusive productivity growth’ (McCann, Reference McCann2021).

1.3. The ‘Levelling Up’ agenda

The term ‘Levelling Up’ first emerged during the 2019 General Election campaign and has now developed into a headline policy priority for the Conservative Government. In an article for the Guardian in October 2021, O’Brien (Reference O’Brien2021) (now a minister at Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities [DLUHC], 2022 and partly responsible for the white paper) set out the Government’s definition:

‘The objectives of levelling up are clear. To empower local leaders and communities. To grow the private sector and raise living standards—particularly where they are lower. To spread opportunity and improve public services, particularly where they are lacking. And to restore local pride, whether that is about the way your town centre feels, keeping the streets safe or backing community life. In his speech, the prime minister also set out what levelling up isn’t. It’s not about cutting down the tall poppies. Not about north v south, or city v town. There are poor places even in affluent regions like the south-east and London’.

But there is also an important political dimension to the agenda and to the issues of long-term regional inequality. The so-called ‘geography of discontent’ (McCann, Reference McCann2019) relates to ‘left behind’ places (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Gardiner, Pike, Sunley and Tyler2021) in those parts of the country (some regions, towns, cities and rural areas) that are both less productive and less wealthy than others (or compared to the UK average as a whole). These are areas that are more likely to be politically dissatisfied with existing institutions as well as economic and social opportunities and outcomes.

Government rhetoric suggests that they can have everything both ways—that they can rebuild ‘left behind’ towns and build globally competitive cities in every region, or invest in high streets and social infrastructure as well as in human capital and R&D. But limited resources and political capital may suggest otherwise. As Jennings et al. (Reference Jennings, McKay and Stoker2021) and others suggest, there will be tensions and trade-offs between improving productivity and growing local and regional economies and the politics of local and regional identity. This is not just in the choices between investment, whether in high streets and the social fabric or in larger structural areas such as infrastructure or skills supply, but also in the geographical boundaries that devolution creates. Local and regional identities do not always follow in the same footprints as the most practical economic development structures and these tensions need to be acknowledged. As recognised by Kenny (Reference Kenny2021), these identities also provide prominent elements of our political discourse and, although longstanding, have perhaps become more significant in local and national narratives since the 2016 EU Referendum and the 2019 General Election.

In many ways, the trick will be to better balance the needs of both. Recent governments such as Labour (1997–2010) may have gone too far on the creation of more technocratic economic structures, including at local and regional levels such as through local LSCs and RDAs. The current Conservative Government may be in danger of going too far the other way, with devolution deals and investment targeted more at local social and political identities.

1.4. What does the ‘Levelling Up’ White Paper say?

After several delays, the White Paper ‘Levelling Up the United Kingdom’ (DLUHC, 2022) was published on 2nd February 2022. In 330 pages, it offers detailed definitions and analysis of England and the UK’s spatial inequality alongside an account of long-term policy ‘churn’ and ‘failure’. Identifying five key shortcomings: a lack of ‘longevity and policy sufficiency’, ‘policy and delivery co-ordination’, ‘local empowerment’, ‘evidence, monitoring and evaluation’ and ‘transparency and accountability’, the White Paper states:

‘Spatial policy in the UK has, by contrast, been characterised by endemic policy churn. There have been repeated changes in the policy landscape over the past century, with each phase signalling shifts at the organisational, legislative and programmatic levels. The result has been a patchwork of policies and ever-changing organisational structures’ (p110).

Alongside a ‘six capitals’ analysis and the setting of 12 long-term policy ‘missions’ to 2030, the white paper also offers the prospect of devolution deals to new areas according to a three-level framework.

The devolution framework is designed ‘to create a clear and consistent set of devolution pathways for places’, according to a set of pre-conditions. The White Paper sets out the Government’s preferred model of devolution, that is, ‘one with a directly-elected leader covering a well-defined economic geography with a clear and direct mandate, strong accountability and the convening power to make change happen’.

Amongst the principles underpinning the framework is a commitment to ‘sensible geography’. However, it acknowledges a trade-off between ‘functional economic areas’—the basis for most devolution deals to date and those ‘that are locally recognisable in terms of identity, place and community’. As this article shows, it is practically difficult to reconcile these different aims and there are inevitable consequences for institutional boundaries and the overall coherence of new arrangements as they emerge. This applies to both the boundaries and powers of new County Deals and also to the future of LEPs. Ahead of the publication of the white paper, there was speculation that LEPs might be abolished. However, the Government have stopped short of that option and opted to incorporate them into devolved arrangements—both existing and emerging—instead:

‘For the last decade, LEPs have acted as important organisational means of bringing together businesses and local leaders to drive economic growth across England. They have also been responsible for the delivery of a number of major funding streams. It is important to retain the key strengths of these local, business-oriented institutions in supporting private sector partnerships and economic clusters, while at the same time better integrating their services and business voice into the UK Government’s new devolution plans. To that end, the UK Government is encouraging the integration of LEPs and their business boards into MCAs, the GLA and County Deals, where these exist. Where a devolution deal does not yet exist, LEPs will continue to play their vital role in supporting local businesses and the local economy. Where devolution deals cover part of a LEP, this will be looked at on a case by case basis. Further detail on this transition will be provided in writing to LEPs as soon as possible’.

Levelling Up the UK White Paper (2022), p. 146.

The integration of LEPs into MCAs and County Deals will be relatively straightforward in some places—where they already share geographic boundaries with them. But in other places—especially where new County Deals are emerging, this may prove to be more complicated and drawn out. Some of these areas are considered in the regional institutional analysis that follows in this article.

However, overall, we can see that the ‘Levelling Up’ White Paper—while recommending more devolution and decentralisation—still adds to the policy churn that has affected local and regional institutions for a long period. It is not clear that the newly reconfigured landscape outlined will be either effective or permanent. This represents a paradox for the relationship between central and local institutions in England—one where changes to local arrangements are continually and frequently driven by national actors in Whitehall and Westminster. Each time, they hope that it is the right policy direction and local institutional configuration and that it is for their successors to leave alone. But that rarely seems to be the case.

1.5. Mapping current institutional structures in regions

We have established that there is a lack of long-term stability in the nature, scope and geographical boundaries of local and regional institutions. To illustrate this empirically, we can closely examine the institutions currently tasked with economic development in different English regions. Most of the institutions described here are relatively new (established within the last decade) and some specific programmes have only been introduced in the last 2–3 years. With the publication of the White Paper, it is clear that these arrangements are fluid and continuing to change with new devolution arrangements and altered roles for some institutions.

For this paper, we have looked at the main regions associated with ‘Levelling Up’ and the so-called ‘red wall’—the Midlands, the North-West, the North-East and Yorkshire and the Humber and mapped current arrangements for economic development in each. We have selected these regions as examples rather than suggesting that these are the only regions where these issues matter (the South-West as well as Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland all have inequalities and economic challenges too—as do more prosperous regions such as London, the South-East and the East of England). However, for the purpose of this paper we have concentrated on institutional arrangements in the three Northern and two Midland regions in England.

In the Midlands—East and West—we can see in Chart 1 that there is a mixture of upper tier and local authorities as we might find in every English region. There are longstanding issues about local authority organisation, boundaries and funding which we do not intend to explore here. But for the purposes of this paper, it is noted that these are perhaps the most stable elements of the local and regional institutional architecture.

Chart 1 also shows the local authority areas that make up the West Midlands Mayoral CA consisting of Birmingham, Coventry, Wolverhampton, Dudley, Sandwell, Solihull and Walsall. This CA, or mayoral city region, enjoys some considerable new powers and resources including over adult skills, transport and some areas of economic development.

However, as both Chart 1 and Chart 2 show, these boundaries are not shared with the three LEPs in the West Midlands. The Black Country sits wholly within the WMCA but the Greater Birmingham and Solihull LEP and the Coventry and Warwickshire LEPs both sit partly within but largely outside WMCA boundaries. In addition, the Greater Birmingham and Solihull and Worcestershire LEPs overlap, with both including towns like Redditch and parts of the Wyre Forest. Integrating LEPs into these structures following the ‘Levelling Up’ White Paper looks likely to be complicated, with several overlapping areas within the WMCA and additional areas where new devolution deals may come forward. Further questions remain about those LEPs that exist currently but in areas with no interest so far in a devolution deal.

Chart 2. (Colour online) LEPs in West Midlands and WMCA boundaries.

Source: The Business Desk (2018)

To make matters more complicated the ‘Midlands Engine’, established under the Coalition Government in 2014, provides an even larger geographical focus including the East Midlands and with a total of nine LEPs.

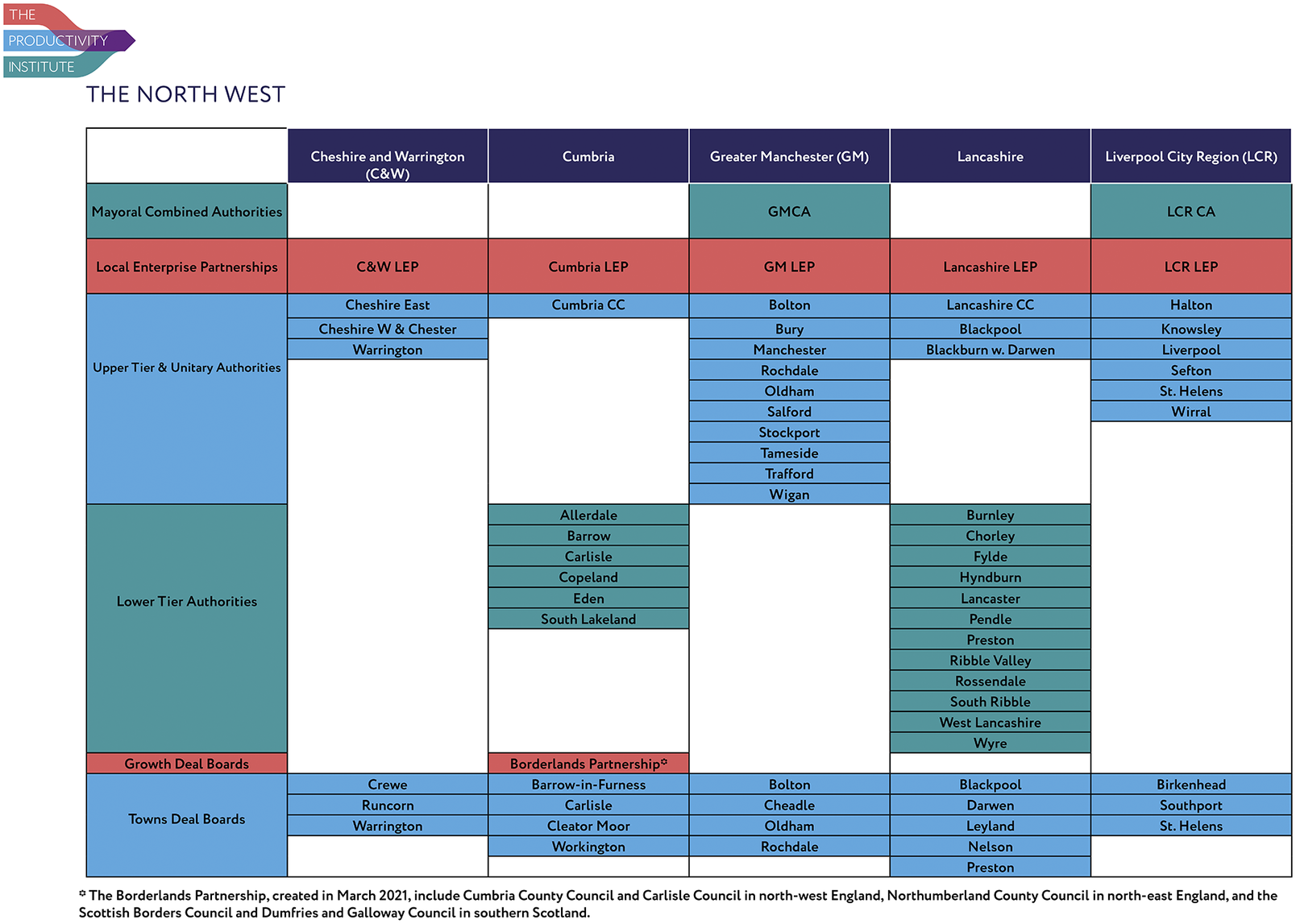

As Chart 3 demonstrates, a first glance at arrangements in England’s North-West suggests similar challenges with another mix of local and CAs, LEPs, ‘Towns’ and ‘City Deals’ in place. There are also some similar ambiguities from the status of the ‘Northern Powerhouse’—an organisation and strategy (like the ‘Midlands Engine’) left over from the Coalition’s time in office and George Osborne’s time as Chancellor of the Exchequer (2010–2016). Like the ‘Midlands Engine’ this also stretches across regions, from the North-West to the Yorkshire and Humber and North-East regions.

Chart 3. (Colour online) Economic development institutions and arrangements in the North West.

Source: Research by authors and TPI North-West Regional Productivity ForumFootnote 4

But at another level there are some clear differences with the Midlands. That is the city region LEPs (Greater Manchester and Merseyside) and CAs are coterminous and are run along the same geographical boundaries. This makes co-ordination significantly simpler in each city region, especially between different organisations that are tasked with improving productivity and increasing economic growth. They are also better integrated as organisations with several joint structures and processes in place in both city regions. Notably, in Greater Manchester this is also aligned with the Chamber of Commerce and in various other GMCA organisations such as those overseeing health and social care. Following the ‘Levelling Up’ White Paper a process of integration into the respective MCAs looks relatively straightforward. The same might also apply to those LEPs currently aligned with potential new County Deals such as in Lancashire and Cumbria.

Charts 4 and 5 set out arrangements in the North-East and Yorkshire and the Humber regions. In both we can see some similarities with both the North-West and the West Midlands. In the Tees Valley the Tees Valley Combined Authority and the Tees Valley LEP are nearly coterminous but for County Durham which is in the LEP but not the CA. There are also Towns Fund and City Deal allocations at a lower spatial level.

Chart 4. (Colour online) Economic development institutions and arrangements in the North-East.

Source: Research by authors and TPI Yorkshire, Humber and North-East Regional Productivity Forum

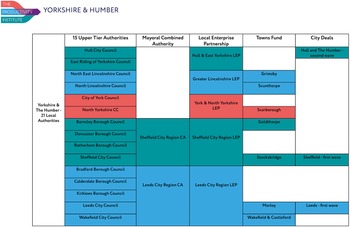

Chart 5. (Colour online) Economic development institutions and arrangements in Yorkshire and Humber.

Source: Research by authors and TPI Yorkshire, Humber and North-East Regional Productivity Forum

However, the North of Tyne Combined Authority (NoTCA)—as its name suggests—has only drawn in local authorities on one side of the river—and the North-East LEP occupies a much larger footprint in and beyond the Newcastle City Region (including County Durham, Gateshead, South Tyneside and Sunderland as well as Newcastle, Northumberland and North Tyneside). Chart 4 also shows that County Durham, Gateshead, South Tyneside and Sunderland all sit between the two Mayoral CAs—currently with a separate non-mayoral CA with fewer of the devolved powers and resources that the neighbouring CAs enjoy. This makes little sense in either governance or economic geography terms. Co-ordinating policies between different organisations will be challenging as will the different arrangements and processes offered to businesses in order to grow any parts of the local and regional economy.

The ‘Levelling Up’ White Paper suggests that the NoTCA will now be expanded to bring in authorities south of the Tyne, including Gateshead, Sunderland and South Tyneside. It also suggests that a subsequent rationalisation of LEP geographies will follow these new boundaries—all of which makes practical economic and spatial sense. However, there is also the possibility of a separate devolution deal for Durham—albeit without a mayor—which suggests that this institutional coherence may only go so far.

In the Yorkshire and Humber region (Chart 5), the LEPS and Mayoral CAs (in South Yorkshire and West Yorkshire) are also run on the same geographical boundaries as the Sheffield City Region and the Leeds City Region LEPs. Though in both the Yorkshire and Humber and North-East regions there are also a range of ‘Towns’ (Grimsby, Scunthorpe, Scarborough, Goldthorpe, Stocksbridge, Morley, Wakefield and Castleford) and ‘City Deals’ (Hull and the Humber, Leeds and Sheffield) in place at lower spatial levels as well as the overarching reach of the Northern Powerhouse described earlier.

2. Competitions, deals and ‘Levelling Up’

Since Boris Johnson became PM in July 2019, we have seen a new set of policy approaches that add to the complexity of governance in local and regional areas. This has involved not only a series of commitments to infrastructure projects but also a series of competitive bidding processes targeting towns, cities and rural areas. These have included the ‘Towns Fund’ and the ‘Future High Street Fund’ as well as ‘Levelling Up’ and ‘Local Growth’ Deals.

Mainly allocated to one-off projects these have come in all shapes and sizes—in terms of governance and geography—and have included funding for projects ranging from R&D and skills to museums, buses and castles. There has been controversy in the classification of local area eligibility for some funding schemes as well as the awarding of projects (see Hanretty, Reference Hanretty2021; Williams, Reference Williams2020) with apparent correlation to Conservative constituencies and especially those seats won in the Midlands and the North from Labour as part of the so-called ‘Red Wall’ (table 2).

Table 1. New devolution framework in England

Source: Adapted from ‘Levelling Up’ white paper (DLUHC, 2022).

Abbreviations: DEM, directly elected mayor; FEA, functional economic area.

Table 2. Regional and local spending schemes in England/UK

Source: Adapted from DLUHC (2022).

But there are other problems with these approaches. First, it applies another set of often random boundaries and eligibility on top of an already crowded and complex landscape. Second, it often replicates activities that well-funded local institutions such as councils or colleges might have been expected to undertake in normal times. Third, the amounts offered compare poorly to the amounts such institutions have seen cut from their budgets during the 2010–2019 period of austerity. The National Infrastructure Commission, in its recent study ‘Infrastructure, Towns and Regeneration’ (National Infrastructure Commission, 2021), summarises the problems with such a fragmented approach:

‘The current fragmented funding for local government has left authorities unable to plan for the long term as the total funding available is uncertain with much funding dependent on bids subject to a patchwork of competitive processes. This way of funding is a substantial impediment to achieving the levelling up goals of government. Local government needs to be given the responsibility and funding that it needs to develop and implement effective infrastructure strategies and wider town plans’.

National Infrastructure Commission (2021)

Whilst the process of allocating multiple pots of funding for different purposes is not new to this Government (the practice dates back to at least the 1980s and the Heseltine–Thatcher approach to local regeneration), it is certainly accelerating as more and more funds are being announced and allocated in this way (see table 2). The announcements have also been increasingly made during major fiscal events, for example, at Budgets or during the Spending Review (see, e.g., the announcement of the first wave of ‘Levelling Up’ funding projects at the Budget and Spending Review in October 2021,Footnote 5 with the precise allocation and implementation to be worked out at a later time).

As has been observed by researchers and commentators (see Bounds and Smith, Reference Bounds and Smith2021; Webber, Reference Webber2020) there are issues in the allocation process as well as in the design and purpose of these projects. Although they do not make up for reductions in local authority budgets over the past decade or offer a long-term solution to challenges such as poverty or low skills, they are politically appealing at both local and national levels. On the day before the Budget and Spending Review in October 2021, the Conservative Leader of Stoke on Trent Council, Cllr Abi Brown said:

‘If you really want to level up places like this city, it won’t be achieved by a succession of beauty parades for small pots of cash for centrally-directed pet projects. It will be secured by one joined up conversation, a commitment to long-term partnership, to a shared vision of what Stoke-on-Trent could become and the resolve and funding to see it through’.

Cllr Abi Brown, Leader of Stoke-on-Trent Council Footnote 6

The next day in the Budget (27th October 2021), it was announced that Stoke-on-Trent had succeeded in three of its bids to the ‘Levelling Up’ Fund, totalling £56 million. The City Council described it as the largest investment in Stoke since 1998.Footnote 7 Between 2010 and 2019, it is estimated that the Council had budget cuts totalling £194 millionFootnote 8 and earlier this year proposed a 4.99 per cent increase in council tax together with £14.4 million of additional budget cuts for 2021–2022.Footnote 9

Alongside the profusion of new funding schemes and competitions, we are seeing different local institutions and actors involved and—as explained above—some existing organisations bypassed. Furthermore, there are invitations and plans for new institutions at local and regional level to add to the already complex and changing picture. In the PM’s ‘Levelling Up’ speech from July 2021, he had identified the need for ‘a more flexible approach to devolution in England’ with more deals to new geographical areas outside of the larger city regions.

‘We need to re-write the rulebook, with new deals for the counties. There is no reason why our great counties cannot benefit from the same powers we have devolved to city leaders so that they can take charge of levelling up local infrastructure like the bypass they desperately want to end congestion and pollution and to unlock new jobs or new bus routes plied by clean green buses because they get the chance to control the bus routes. Or they can level up the skills of the people in their area because they know what local business needs’.

Boris Johnson Speech on ‘Levelling Up’ July 2021

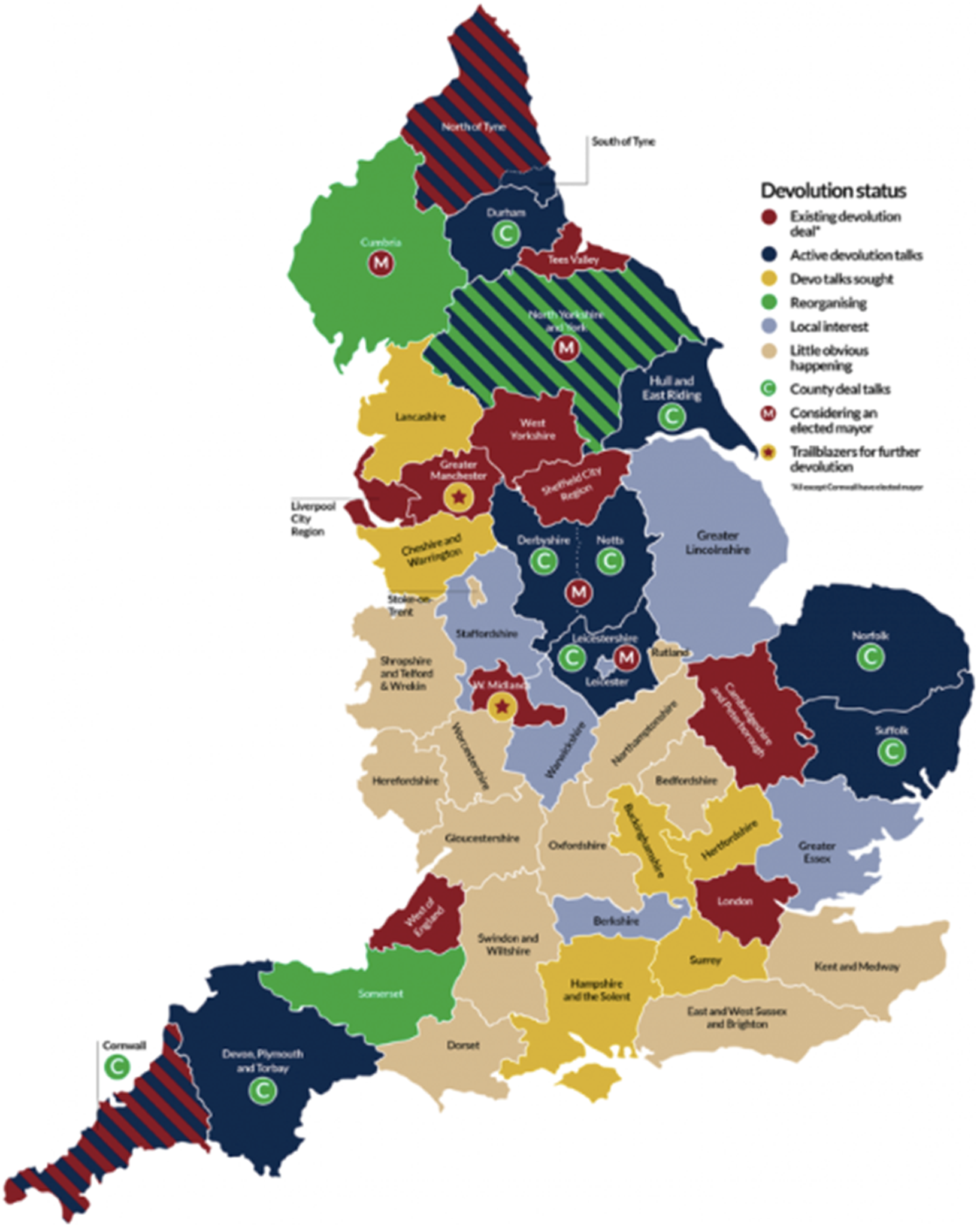

According to the ‘Levelling Up’ White Paper, a number of new devolution deals are now currently being negotiated. Alongside the recasting of the Mayoral CA in the North East, these include Cornwall, Derbyshire and Derby, Devon, Plymouth and Torbay, Durham, Hull and East Yorkshire, Leicestershire, Norfolk, Nottinghamshire and Nottingham, and Suffolk, with the Government aiming to agree deals by Autumn, 2022. However, according to the Local Government Chronicle (see Chart 6) this invitation, together with the formalised devolution framework set out in the ‘Levelling Up’ White Paper and summarised above, is bringing forward new devolution proposals from a number of additional areas, including Bedfordshire and Northamptonshire, Cheshire and Warrington, Surrey and Cumbria, Lancashire and Staffordshire and Stoke on Trent.Footnote 10

Chart 6. (Colour online) Possible county devolution deals alongside existing arrangements (LGC 2022).

Source: Local Government Chronicle (2022) Devo Map finds new devolution deals in sight as negotiations begin, 7th March 2022: https://www.lgcplus.com/politics/governance-and-structure/exclusive-devo-map-finds-new-deals-in-sight-as-negotiations-begin-07-03-2022/

This suggests a number of overlaps and potential flashpoints with existing devolution deals and structures as well as a much more diverse and varied landscape overall.

Even with proposed changes to LEPs and their eventual incorporation into devolution structures, the prospect of many new devolution deals at county (and combined county) levels suggests that there will still likely be an institutional picture with many overlapping geographies. Furthermore, it may also be that this is combined with an acceleration of centrally designed funding competitions targeted at particular activities such as high streets, ‘towns’ or the broader objective of ‘restoring civic pride’. Taken together this is likely to create an unstable and incoherent institutional landscape in the short and longer term.

3. Conclusions

This chapter sets out the many layers of local institutions currently operating in England, including the new arrangements in train since the publication of the ‘Levelling Up’ White Paper. It also describes further policy and institutional or organisational fragmentation emanating from a raft of new schemes relating to economic development and ‘Levelling Up’. Together these illustrate some of the challenges facing the Government as they try to address longstanding local and regional inequalities including excessive levels of centralisation, fragmentation and policy short termism.

We began the chapter by describing how important local and regional institutions will be to the ‘Levelling Up’ agenda and by setting out how academic disciplines sometimes define them differently. However, it is reasonably clear that current (and likely future) arrangements fall short by any definition. Not only are there problems for those organisations operating at local and regional level—whether local authorities, partnerships or those important to policy delivery such as colleges and universities—but there are also fundamental challenges when we think about institutions as the ‘rules of the game’ or the relationships and ‘norms’ within which different organisations and actors operate. In the recent, current or emerging environment, it is a Sisyphean task to understand what the rules of the game might be—because they change so frequently and because they can be so bureaucratic and opaque.

Furthermore, the levels of trust for policy delivery, levels of resource and decision-making between the centre and the local and regional are low—from both directions. There appears to be a reinforcing of the ‘Westminster Model’, with continued centralisation of powers and resources even by recent governments standards. The centres—both Westminster and Whitehall—remain all powerful in both policy development and resource allocation at local levels with little interest in local or regional institutional capacity or stability. It is notable that the Treasury—by far the strongest domestic department in Whitehall—which, although initially a driver of devolution deals and political accountability via elected mayors, has only shown limited interest in the ‘Levelling Up’ agenda and new devolution deals. Neither does it seem to have very much appetite for decentralising fiscal powers from the centre to the local or regional level. Its new ‘Northern Campus’ in Darlington (alongside other departmental relocations to places like Wolverhampton, Leeds and Salford) perhaps demonstrates a greater commitment to the symbolism of moving civil service jobs and spreading the power and influence of the centre rather than devolving actual powers and resources.

But any changes to this model and to our longstanding governing culture are likely to take more than through a consideration of the best arrangements for economic development and/or improving productivity at local and regional levels. Instead, it may be that the best arrangements for local and regional economic development may not be realised until this culture of centralisation changes, that is, potentially a much longer-term project.

There is a very practical aspect to these competing and overlapping arrangements and that is the complexity experienced by businesses as they try to access support or to collaborate or plan with public institutions. If they are based in certain parts of the country, do they know who to speak to for help? Or if they are an investor from overseas looking to establish a new base or manufacturing facility? Is it the mayor or a local authority leader? Someone from the LEP or the Chamber of Commerce? Perhaps the CA has a development company or offers business support services? Or is it a sectoral matter and enquiries should go to Innovate UK or to a local university with R&D funds for knowledge transfer? There are likely to be several ‘right’ answers depending on the business, its location and the nature of its question. This is at the heart of the co-ordination challenge. But it is also a challenge for local, regional and national authorities, because they may simply walk away or not bother to try in the first place.

The ‘Levelling Up’ White Paper has clarified some issues, such as the status and eventual geographical reach of LEPs. But it has also produced a new devolution framework that offers new powers to a range of very different local government arrangements and boundaries. In particular, the emergence of county (and what we might call combined county) deals means we are likely to see a range of different institutional and geographical arrangements in different parts of England. Some will overlap with other key institutions relating to economic development.

It fails then to create a coherent institutional framework or the stability and better co-ordination between institutions (within localities and regions as well as between them and national organisations) that is required. Perhaps such an ambition implies a degree of consensus across political parties, which is not easy to achieve. But if the alternative in England is to chop and change local and regional institutional and policy arrangements every time there is a change in government (or in Prime Minister), then we have a problem in which instability, inequality and low productivity become long-term features of our political economy. That may be a worse problem.

Furthermore, even with a new devolution framework and pilots to deepen arrangements in two English CAs (the West Midlands and Greater Manchester) England still lacks a clear devolution and decentralisation strategy with enhanced powers and resources at the city region and local levels. Local and CAs are the right building blocks and ‘Levelling Up’ will be significantly more likely if they are acknowledged and supported appropriately. This should involve a clear ‘direction of travel’ for any new devolution deals or arrangements and a commitment to build capacity and capability as such deals are rolled out.

Finally, while symbolism and identity can improve the political appeal of ‘Levelling Up’, trading it off against institutional coherence and co-ordination is not the best basis to address long-term inequality and low productivity. In devolution and policy delivery, the Government should resist a ‘thousand flowers blooming’ approach (as well as the centrally determined competitions that support them). They will not all work. Indeed, if some of the fundamental institutional issues are not addressed at the same time, there is a risk—both economic and political—that very few will work at all.